#clash of civilizations

Photo

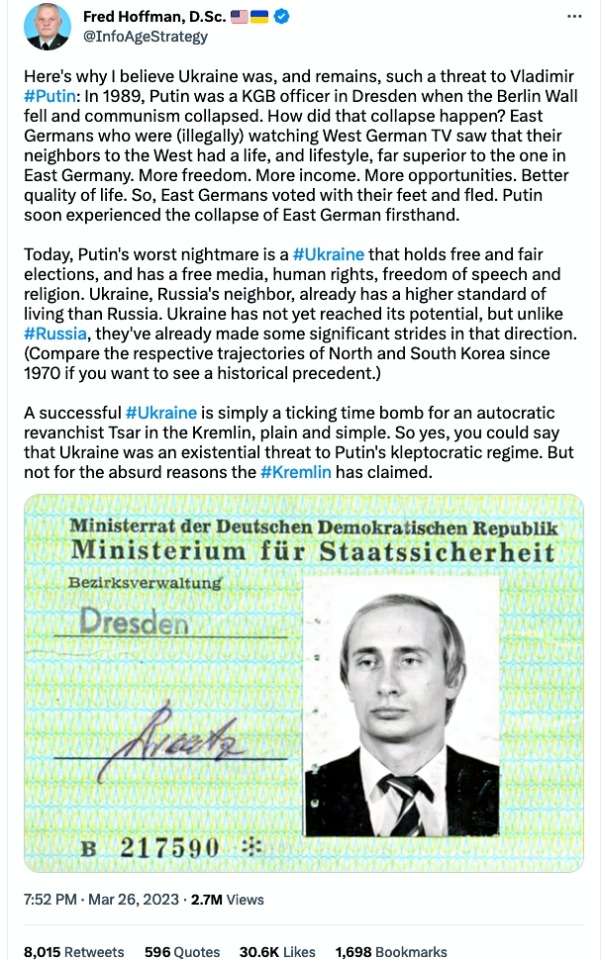

^^^ From @InfoAgeStrategy.

Prof. Fred Hoffman is a retired US Army human intelligence officer and US military attaché in Germany. He served in Germany around the same time Vladimir Putin was a lieutenant colonel in the KGB stationed in Dresden in the now defunct East Germany (”German Democratic Republic”).

Prof. Hoffman believes that Putin hates Ukraine because the Russian dictator sees it as a hotbed of democratic contagion which could spread to Russia. Putin blamed West Germany for corrupting the glorious communist East Germany with ideas about democracy, freedom, and higher standards of living.

Putin’s war is largely a clash of civilizations between modern Western democracies and kleptocratic autocracies. Putin’s invasion of Ukraine was essentially a declaration of war against the West. People who characterize the war as a “territorial dispute” are putting on public display their farcical ignorance of Russian history and Eastern Europe.

#invasion of ukraine#fred hoffman#vladimir putin#kgb#east germany#ddr#democratic contagion#putin's hatred of ukraine#clash of civilizations#putin's war against the west#revanchism#россия#владимир путин#кгб#бывший ссср#путин хуйло#восточная германия#рдр#война против демократии#путлер#союз постсоветских клептократических ватников#вторгнення оркостану в україну#україна переможе#слава україні!#героям слава!

682 notes

·

View notes

Text

“A wave of terror and horror is breaking over us all. I don’t have the heart to do much besides wait for news to trickle out from the hospital in Pennsylvania where Salman was taken by helicopter and let the memories come back to me—my memories of Salman Rushdie over the 33 years that have passed since Ayatollah Khomeini publicly sentenced him to death.

(…)

Another cowardly soul comes to mind. This one was once France’s foreign minister, Roland Dumas. La Règle du jeu, a literary magazine that Salman and I and some others founded in 1990, invited Salman to come to France to meet up with some of his Parisian friends. As I remember, the minister behaved shamefully, decreeing that Salman, a citizen of Europe, needed a visa to enter France. Then he denied the visa on the grounds that he couldn’t guarantee Salman’s security. Dumas’s own colleague, Minister of Culture Jack Lang, protested. My friend the businessman François Pinault offered to lend us a plane and to provide the necessary protection. President François Mitterrand himself had to settle the matter. And lo, the France that was hoping for trade deals and arms sales yielded to the spirit of Voltaire. Bienvenue, Monsieur Salman.

Yet another spineless individual: Prince Charles. In 1993, I met him at a lunch hosted by the British embassy in Paris. “Salman is not a good writer,” growled the prince when I asked him what he thought of the whole affair, adding that “protecting him costs England’s crown dearly.” On this, Martin Amis, another of Salman’s friends, later remarked: “It costs a lot more to protect the Prince of Wales, who has not, as far as I know, produced anything of interest.” The press and public opinion, for once, took the side of the persecuted writer.

(…)

I remember a conversation we had in front of an audience in London, where Salman said how much he missed the Islam of his childhood in India. “The greatest of Muslim thought has been broad-minded,” he explained. “When I think back to my grandparents’ time, my parents’ time, Islam strove to be cosmopolitan. It raised questions and engaged in argument. It was alive.” Salman is the son of that form of Islam. He obviously has nothing against blasphemy, because blasphemy, in his eyes, is inseparable from freedom of expression and thought; but neither do I believe that he has ever blasphemed against the creed of his parents.

I remember a conversation between us, in Paris, on the Jewish radio station RCJ, when he speculated on what the fatwa would have entailed if it had been issued in the era not of the fax machine but of social media. “A tweet is all it takes,” he said, as I recall, “to stir up the planet. Five minutes on YouTube is enough to trigger simultaneous demonstrations throughout the world. If my fatwa had occurred in the internet age, would it have been fatal? I don’t know.” Now he knows. Alas.

(…)

I remember a day on the beach in Antibes, the pleasure of being alive, the noon sun, heat waves rippling as far as you could see, sharing a love of movies and actresses, especially Jean-Luc Godard’s Contempt, the real owner of the Casa Malaparte in Capri (which Godard used as his film’s main setting). That day, Salman wanted nothing so much as to be able one day to do a remake of Dr. No or From Russia With Love. The good life. An appetite for living and for multiplying the ways of living. The opposite of a condemned man.

(…)

I mull over our dinners together in New York in recent years. He didn’t want to hear any more about the fatwa. We talked about François Rabelais, Toni Morrison’s Song of Solomon, Laurence Sterne, George Eliot (a writer he could never get into), and V. S. Naipaul, whose death had devastated him. Literature before and above all else! The wish, faced with the fracas of the world, to say, “Please, turn down the sound!” Which obviously did not prevent him, a few months ago, at the very beginning of the war in Ukraine, from deciding that it was urgent for us to pen an appeal for sanctions against Russia and to help persuade Sting and Sean Penn to join the campaign.

What has struck me, over all these years, is the quiet heroism of my friend. He understood very well that, from time to time, a Western government would expel a fake Iranian diplomat and that this might be out of concern for his safety because of the fatwa. He knew that self-styled friends of the Muslim people were still insisting, despite the Charlie Hebdo massacre and other slaughters, that no one had the right to offend others’ faith and that, if harm should befall the offender, he had only himself to blame. And never did a speaking engagement go by without his being asked the eternal question: Knowing everything he knew today, did he ever regret having written The Satanic Verses, a work that has followed him like a curse?

(…)

And once—just once, a long time ago—I heard him make an odd remark about the knack master killers have for ruminating on their vengeance and carrying it out coldly when least expected. Think Mussolini and the Rosselli brothers; Stalin and Ignace Reiss; Putin and the poisoned oligarchs. And one day, a Shiite Ramón Mercader whom no one would see coming.

I believe that is where things stood, last Friday at the Chautauqua Institution, when Salman Rushdie saw the man who meant to execute him leap onto the stage.

Will this still be where things stand when he emerges from the hell of pain in which I imagine him? The artist in him will continue to believe that life is a tragedy, a tale full of sound and fury, told by an idiot. And he will not be surprised to hear friends tell him that if one can be Dickens, Balzac, and Tagore in a single life, one could well be considered immortal.

But he will read the article in Iran, the semi-official newspaper of the regime, which, while he was fighting death, rejoiced that “the devil’s neck” was “struck with a razor.” He will see the ultraconservative newspaper Kayhan pronouncing a blessing, while he was recovering, on “the hand of the man who tore the neck of the enemy of God with a knife.”

And Salman will have to get used to the idea, one that always petrified him, of being a human symbol, a hostage in a war of the worlds in which, like it or not, his own life and death have become everybody’s business. That is why those of us who could not protect him—all of us—now have a duty to perform.

This act of terror against his body and his books is an absolute act of terror against all the world’s books. Such an outrage against freedom of expression calls for a ringing response.

Individual nations will have their say. The international community, too, must signal to the sponsors of this crime that this Salman Rushdie affair has created a new division, a time before and a time after.

As for his friends, his peers, media, and others for whom public opinion counts for something, we all have a commitment to make. And that is to ensure that the author of The Satanic Verses receives the highest of literary honors. To see that, in the name of all his fellow authors and in his own name, Salman Rushdie receives the Nobel Prize in Literature that is due to be awarded in a few weeks.”

“In October, the Swedish Academy will have the opportunity both to chip away at its record of overlooking many of the most profound writers in its field of vision and to help correct its woeful hesitation in standing up for the values it ought to champion. In the mid-nineteen-eighties, Salman Rushdie’s masterpieces, “Midnight’s Children” and “Shame,” had been translated into Persian and were admired in Iran as expressions of anti-imperialism. Everything changed on February 14, 1989, when Ayatollah Khomeini condemned as blasphemous “The Satanic Verses,” a novel that he hadn’t bothered to read, and issued a fatwa calling for the author’s death. Khomeini’s edict helped inspire book burnings and vicious demonstrations against Rushdie from Karachi to London.

Rushdie, who could never have anticipated such a reaction to his work, spent much of the next decade in hiding and under heavy guard. The literary world was hardly unanimous in his defense. Roald Dahl, John Berger, and John le Carré were some of the writers who judged Rushdie to have been insufficiently attentive to clerical sensitivities in Tehran. Among the more cowardly acts of the time was the Swedish Academy’s refusal to issue a statement in support of Rushdie. The Academy waited twenty-seven years—a period during which booksellers in the United States and in Europe were firebombed and Rushdie’s Japanese translator was murdered––before it roused itself to condemn the fatwa as a “serious violation of free speech.” Stern stuff.

Rushdie, for his part, behaved with impeccable bravery and, even more remarkably, with good humor. As he put it in a recent essay, “While I had not chosen the battle, it was at least the right battle, because in it everything that I loved and valued (literature, freedom, irreverence, freedom, irreligion, freedom) was ranged against everything I detested (fanaticism, violence, bigotry, humorlessness, philistinism, and the new offense culture of the age).”

Through it all, Rushdie never stopped writing, and, eventually, he emerged from his highly sequestered existence and resumed teaching, lecturing, and enjoying himself. The tabloids seemed aghast that he would dare go to parties, concerts, and ballgames, as if this somehow undermined his standing as a hero of the free word. He didn’t care. He was so insistent on living his life without performing the role of a “Statue of Liberty,” as he put it, that he played himself on an episode of “Curb Your Enthusiasm,” counselling Larry David on the forbidden pleasures of “fatwa sex.” Solzhenitsyn was capable of many deeds, but not that.

At the same time, no one in our era has been a more tireless champion of free speech. As an essayist and as the president of pen America, Rushdie spoke up for artists, writers, and journalists everywhere who were under assault. He has been especially vigilant in recent years about threats to free expression in the two largest democracies: India, where he was born and raised, and the United States, his adopted home for the past two decades. His judgments could sting. When a group of six writers refused to attend a pen gala, in 2015, because it was honoring the editors of the French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo, Rushdie said, “If pen as a free-speech organization can’t defend and celebrate people who have been murdered for drawing pictures, then frankly the organization is not worth the name.” Of the writers who spurned the dinner, he said, “I hope nobody ever comes after them.”

(…)

As a literary artist, Rushdie is richly deserving of the Nobel, and the case is only augmented by his role as an uncompromising defender of freedom and a symbol of resiliency. No such gesture could reverse the wave of illiberalism that has engulfed so much of the world. But, after all its bewildering choices, the Swedish Academy has the opportunity, by answering the ugliness of a state-issued death sentence with the dignity of its highest award, to rebuke all the clerics, autocrats, and demagogues—including our own—who would galvanize their followers at the expense of human liberty. Freedom of expression, as Rushdie’s ordeal reminds us, has never come free, but the prize is worth the price.”

“When the Rushdie affair took off in early 1989, America’s campus culture wars had only just begun. Although I was riveted by both controversies, I would not have connected them at the time. What was then called political correctness (now called “woke”) seemed to be something of a different order than the command of a religious ruler to execute a literary figure in the name of the Muslim faith.

Yet the professors who kicked off the campus culture wars did see a link. They argued that globalization requires us to demote or abolish the Western civilization narrative. Eurocentrism must go, they said, since the sensitivities of ethnically non-Western students were on the line.

(…)

In those days, there was plenty of academic controversy around Samuel P. Huntington’s 1996 book, The Clash of Civilizations. Probably no book has more successfully predicted the war on terror that soon followed, or the rise of China that preoccupies us today. Yet academics uniformly slammed Huntington’s book for the sin of “essentialism.” Huntington was supposedly guilty of overplaying cultural difference, while underplaying the extent to which cultural borders overlap, interpenetrate, and blend. In other words, the same academics who treated cultural difference as real and significant — especially when criticizing the West — could turn around and “deconstruct” the supposed illusion of culture when the issue was non-Western intolerance. For academics, Huntington’s book became one more reason to shun the teaching of Western civilization, and indeed to abandon the word “civilization” itself.

(…)

Surveys now show that up to two-thirds of students approve of shouting down campus speakers, while almost a quarter believe that violence can be used to cancel a speech. These are the views of the generation that grew up without required courses in Western civilization, a course the core theme of which was the long, bloody, and difficult path by which our freedoms were conceived and established. Those courses nurtured a sense of reverence around our liberties, and a sense of shame in those violating the liberties of others. We have lost both the reverence and the shame.

The upshot is that globalization has made us more vulnerable to foreign threats, while our misguided response to globalization has damaged our greatest weapon against those very threats: our regard for our own tradition of liberty, and the principles that lay behind it. Our horror at the assault on Rushdie is a sign that there is life in our tradition still. The culturally alien nature of the attack reminds us that our tradition of freedom is real, distinctive, and worth preserving. Yet our continuing reluctance to affirm our own history and principles — especially in our schools — means that time is running short. Freedom, so to speak, is on a ventilator. We cannot remain a “safe haven for exiled writers” if we are not a safe haven for ourselves.”

#rushdie#salman rushdie#bernard henri levy#levy#huntington#samuel huntington#clash of civilizations#free speech#freedom of speech#first amendment#nobel prize#western civilization#stanley kurtz

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

How we got here

#Zionism#cults#end times#British Israelism#Darbyism#Islamophobia#clash of civilizations#Muslim Brotherhood#Evangelicals#John Hagee#psychological operations

0 notes

Text

Norms, Power, and the Western Delusions of Benevolence

Dive into a compelling critique of Western self-perception as benevolent powers in this insightful blog post. Uncover the complexities of cultural norms, political orders, and the often overlooked role of power in shaping these norms. #Norms #Power #West

Cultural norms shape the emergence and evolution of political orders. However, these norms are not static or homogeneous, but rather dynamic and diverse, reflecting the power relations among different actors in local and global contexts. Huntington (1996) argued that the clash of civilizations, or the cultural conflict between different regions and groups, is the main source of global instability…

View On WordPress

#Clash of Civilizations#Colonianlism#Cultural Identities#Cultural Norms#De Tocqueville#Elites#Global Elites#Global Instability#Human Societies#Huntington#International Norms#Political Orders#Political Outcomes#Post-Cold War Era#Power#Power Distribution#Power Relations#Rules-based Order

0 notes

Text

THE CHILDREN OF GAZA

We hear a lot about the children of Gaza on the news. Whenever a bomb or missile hits, there are always plenty of children to be carried into the hospital. 50% of all the people in Gaza are children. With all the TV news footage showing the suffering in Gaza, it’s very difficult to stay focused and to think straight. The latest war between Israel and Hamas began with a gruesome attack on…

View On WordPress

#Alireza Panhian#Armistice Day#Bangkok#Berlin#birth control#boat people#China#Christians#clash of civilizations#Douglas Murray#Ernst Reichel#Gaza#German Empire#Germany#Hamas#Hanan Hashwari#holocaust#islam#Israel#Khamenei&039;s Think Tank#London#Muslims#Naxi era#Palestianians#Petra Sigmund#Rent-A-Mob#Rishi Sunak#Samuel Huntington#Suella#Suella Braverman

0 notes

Video

youtube

The Voyage that Changed it All: Ferdinand Magellan's Arrival in the Phil...

#youtube#ferdinand magellan#voyage#philippines#spanish colonization#history#exploration#conquest#cultural fusion#adventure#epic journey#indigenous culture#clash of civilizations#transformative moment#heritage#discovery#treacherous seas#watershed event#exotic islands#brave explorer#Impactful legacy

1 note

·

View note

Text

#ancient civilizations#history#ancient#world history#wall streeet journal#fox news#my journal#sky news#historical#journal#culture#lost civilization#early civilization#civilization collapse#civilization as we know it ‘is ending’ and humans could face biggest extinction event since dinosaurs#clash of civilizations#western civilization#ancient world#china

0 notes

Text

2022: Russian Perspective -- Russia and America in the 21st Century: The Logic of Civilizational Confrontation

A Russian Academy of Sciences researcher applies a so-called :”realist perspective’ and a long view of Russian-American relations leading up to now the USA is apparently intent on the dismemberment of the Russian Federation. Translation via a DeepL Russian-English machine translation. I added a few links.

Vasilyev ends with some kind of post-Soviet anti-semitic eruption. “From this point of…

View On WordPress

#Alaska#American#civilization#clash#clash of civilizations#colonial#confrontation#crisis#cvilization#Васильев Владимир Сергеевич#empire#Fort Ross#history#human rights#realist#Russia#Russian#Russian Academy of Sciences#Russian Federation#Russian Orthodox#slav#theory#Ukraine#Ukrainian#values#war#Woodrow Wilson

0 notes

Text

This is one of the things that's wrong with the west. They don't know who their enemies are.

0 notes

Text

And for another installment of "Tropes that Excite me"

The Hero and Villain having a civil exchange or doing an activity that is not them fighting but clearly showing their difference in ideology. Classic trope being Chess, but it could be anything. It could even be them talking while watching others play a game, while the players mirror that show the protagonist and antagonist's style.

One of the best examples is L and Light playing Tennis against one another. Showing the back and forth and foreshadowing their entire clash in the series.

#tropes#the hero and villain being civil but ideology clashes#the philosophical clash can be just as stimulating

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

WAIT WAIT NO HOW OMG ASHBORN AND ANTARES DO EMBODY ROME VS CARTHAGE AND BIZANTINE VS HRE HOW IN THE HELL—

#ARTIST BRAIN ON LIKE OMGGGGGG#YOU TELLING ME MY FAVORITE CIVILATIONS CLASH HAVE THE SAME FUKING VIBES AS THESE OLD MEN#I NEED TO DRAW THEM IN THIS RN OMG#solo leveling#sl ashborn#sl antares#soulfire and ashes

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

one of the weirdest media experiences for me is when there's a clear Choice that's been made but i can't even start to explain why - i'm good at evaulating whether a Choice works or falls short of what it seems like it's trying to do in a work, but sometimes there's an element that someone put a lot of effort into and couldn't have done accidentally but it's just not even touching what seems like the thematic thrust of the rest of it --

most recent is the post-apocalyptic game where the evil upper class wears full 1780s French aristocrat clothes (sure, good, seems like a lot of work to produce, but it makes some thematic sense) but some fancy areas of the city are 1920s high society and others are, like, 1880s, and this is supposed to be doing something, i know it, but i'll be dammed if i know what.

#on reading#it's like i'm a cat staring at the door trying to make it make sense#another example is the space opera where the clashing civilizations were the Regans and the Sassanids or something#so i was like 'are we doing a rome vs. persia but (because someone also had Companions) alexander the great is there too thing on purpose?'#and it was very distracting

24 notes

·

View notes

Link

Christian Zionism predates Jewish Zionism, and perhaps even caused it

#Christian Zionism#colonialism#supremacism#clash of civilizations#nationalism#extremism#fanaticism#heresy#politicization#warmongering#neoconservatism

0 notes

Text

The Clash at Naseby

The battle of Naseby was a decisive battle during the war and was the battle that show the effectiveness of the parliamentary New Model Army. However, my drawing isn't depicting that, but the clash at the parliamentary right between the Ironsides led by Oliver Cromwell and the royalist cavalry. The Ironsides managed to break the royalists cavalry and then charge the rear of the royalist infantry, wining the battle.

As an interesting fact, the left led by Henry Ireton didn't have a lot of luck and were put to rout by Prince Rupert's cavalry, but the latter decided to plunder the parliamentarian baggage train instead of attacking the infantry. At the time they returned to the battlefield, Charles I had ordered the retreat.

If you have trouble in telling who is who, just remember that the parliamentarians used orange sashes and the royalists red ones. And yes, I copied the Ironside with the pistol from an illustration made by Graham Turner. I needed a guy there and didn't knew what to do...

#armor#art#war#civil war#english civil war#english#england#parliament#17th century#cavalry#clash#history#historical art#history art

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

consistent lilith mood for the past seven years: sera when i catch you sera when I Catch you Sera When I Catch You -

#'what are you doing with this little girl. *what* are you doing.'#'*why* is she in the dark the way she is. talk to me.'#(( <- of course is NEVER going to confront sera about this. this is private.#but oh man that's the mood. ))#(( lilith and sera constantly debating constantly clashing constantly locked in ~civil political arguments~ .#Frustrated As Hell / Tired. ))#[ thread commentary. ]

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

the Unova games are the best games to ever come out with the subject around the United States of America, and no one will ever change my mind on that

#the game has cults and terrorist attacks#it has mass brainwashing#it has ideological struggles that result in people clashing#it has girls who are told they can't become anything and controlled by their father#it has an evil ring of relatively few bastards who virtue signal and using that to start gang warfare#those few bastards who's only goal is the acquisition of power meanwhile their peons are the ones on the front lines#and those peons being the only ones having serious debate on what kind of civilization they want to have#we have robbing families of connections (Purrloin B2W2) and inflicting generational trauma from these thefts#I think the only base it fails to touch on is real poverty but honestly if the bad guys were successful like in America then it'd come#it's literally named black and white and the entire message is about coming together with our opposition#to see the evil that is using our conflicts against us#it also has basketball football hollywood and surf bros so yanno lmao#unova#pokemon black and white#pokemon black 2 and white 2#us politics

9 notes

·

View notes