#constituent morphemes

Text

How does one describe the process of compounding in morphology?

Compounding is a morphological process by which two or more individual words are combined to create a new word with its own distinct meaning. This process is used in many languages around the world, and it is an important aspect of word formation in morphology. In this article, we will describe the process of compounding in morphology, including its types, formation, and examples.

Continue…

View On WordPress

#bound morphemes#Compounding#constituent morphemes#direct compounding#free morphemes#homophones#hyphenated compounding#internal structure of words#linguistic irregularities#Morphology#neologisms#open compounding#semantic analysis#syntactic analysis

0 notes

Note

Hey, I don't usually ask stuff on tumblr but... What does the "I" in "IP" stand for? (I'm sorry if my sentence is grammatically incorrect as English is not my first language )

So the long and the short of it is that in non-derivational theories it doesn't really stand for anything much anymore - sort of.

Historically, "I" stood for "Inflection", with IP being the Inflectional Phrase. This is because, in certain early movement-based theories of syntax, the inflected part of an inflected verb moved to I.

These days, most mainstream syntactic theories hold by some form of the lexicalist hypothesis* (i.e. syntactic rules can't "see inside" words and operate on their constituent components), so you generally don't posit just the inflection of a verb appearing anywhere alone in the structure. However, the IP is still where "inflected material" tends to appear - in English, it's where inflected auxiliaries go (mostly); in Russian, it's where the main inflected verb goes; in Warlpiri, it's where the inflected auxiliary goes; etc.

TL;DR - it stands for "Inflection", but really means "inflected verbal material".

* The exception here is Distributed Morphology and the various frameworks derived from it, such as LrFG. I personally find these frameworks silly and implausible - there is a reason the field of morphology pretty much entirely ditched morphemes a decade or two ago now - but they do exist and are gaining traction in some parts of the field, so I guess I am obliged by academic integrity to at least mention them.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

A head movement analysis of second position clitics: The case of Russian polar particle li.

Russian polar particle li is usually analyzed as a second position clitic, constrained to appear at the linearly second position in the clause. I suggest that this requirement is a consequence of head movement: li is generated in ∑—a polarity projection—merged directly above the associated polar constituent (X). This constituent must head-move and left-adjoin to li. The complex head (X+li) is largely equivalent to a wh-word: at later stages of the derivation, it is attracted to the left periphery of the clause. li can be seen as an analog of a wh-morpheme, which merges with different morphemes to form a wh-word. Treating X+li as a complex head allows us to reduce the second position requirement of li to the left edge requirement on the X+li, a requirement often postulated for wh-words. I provide further evidence for the ∑ hypothesis by showing the complementarity of li and negation.

A head movement analysis of second position clitics: The case of Russian polar particle li.

0 notes

Text

the strictest feature of my word order seems to be the level of privilege that constituents get when it comes to being able to remain attached to their root during movements. higher privilege means more relevancy to the root, but is punished by high rigidness in syntax.

it generally seems to be based on how "large" the constituent is, on average? i know that big constituent = looser sounds tautological, but i'm talking more about average size of that constituent type than pure size as in morpheme count.

the most privileged class are adverbs. or rather the adverb? adverbs are a closed class, there's like ten of them. several adverbs are mutually exclusive with others. they always have a strict order relative to one another. they will follow their root noun or verb religiously, acting more like prefixes than modifying particles.

though there are of course exceptions. tau behaves like an adverb with verbs, and is mutually exclusive with adverbial si. Yet with nouns, that exclusivity no longer applies, and it only needs to obey looser adjectival placement rules.

adjectives on nouns are almost adverbial? they're a much freer class, in terms of being open and also their free orders relative to each other, deferring only to lexicalised compounds and focus-marking. but when it comes time to move the subject into a relative clause, they'll follow. or rather the entire RC will shift into post-position? end result is the same. the noun and adjectives did one thing, the RC the other.

once you get up into proper constituents, though, headed by clausals? there's like 3 rules. but even they're more like guidelines. and after all that? all bets are off. these things are shuffling as if party rock anthem is playing. only in strict situations, to be fair, but said "strict situations" are at this point often just as dependent on the semantics of the constituents as they are anything syntactic.

it's almost free word order! if you consider large compound constituents words, of course. high gavellian does. sometimes.

and then sentences can come in pretty much whatever order you want. as long as you're coherent, ig, but syntax no care about "coherency" of statement.

0 notes

Text

What is a morphological analysis?

Morphological analysis involves breaking down a word into its smallest units of meaning, known as morphemes, and studying their structure and function. Here's a step-by-step guide:

Identify the Word: Choose a word for analysis. This can be a complex word or a word with multiple morphemes.

Divide the Word into Morphemes: Split the word into its constituent morphemes. Morphemes can be either free (stand alone) or bound (attached to other morphemes).

Identify the Morpheme Types:

Free Morphemes: Those that can stand alone (e.g., root words).

Bound Morphemes: Those that need to attach to other morphemes (e.g., prefixes, suffixes).

Analyze the Morpheme Functions:

Determine the grammatical function of each morpheme (e.g., whether it indicates tense, number, or if it changes the word's meaning).

Explore the Word's Meaning: Consider how the morphemes contribute to the overall meaning of the word.

Example:

Let's analyze the word "unhappiness."

Identify the Word: "Unhappiness"

Divide into Morphemes:

Un- (prefix)

Happy (root word)

-ness (suffix)

Identify Morpheme Types:

Un- (bound prefix)

Happy (free root word)

-ness (bound suffix)

Analyze Morpheme Functions:

Un- (negation)

Happy (base meaning)

-ness (noun-forming, indicating a state or quality)

Explore Word's Meaning: The word means the state of not being happy.

0 notes

Text

Calls: The 15th Workshop on Phonological Externalization of Morphosyntactic Structure: Theory, Typology and History

Call for Papers:

Possible topics include:

Topic 1: The mechanism of Externalization

Topic 2: Linear order of constituents, morphemes, and/or phonemes

Topic 3: Mapping of syntactic structure onto phonological structure

Topic 4: Phonological approaches to syntactic phenomena

Topic 5: Diachronic study of the syntax-phonology interface

Please submit an anonymous abstract (A4 PDF) of no more than 1 page (excluding references) by

EasyChair: https://easychair.org/conferences/?conf=phex15

The d http://dlvr.it/SyYtLD

0 notes

Note

do you ever think about the logical parallels in language that we don't use because they sound weird? Like for example, the exact ontological opposite of the word "upcoming" is "downcome", but no one says that, because calling, say, every film that has been released "a downcome [year] film" on its Wikipedia page sounds stupid

as far as I can tell these are very very different words and definitely not exact opposites (the exact opposite of its constituent morphemes would be downcoming and that's not a word), so I think your example is flawed

but yeah, the topic is really interesting and it is super funny how little language cares about being logically coherent throughout. That one comic that makes the rounds sometimes about "I'm up for this" and "I'm down" meaning the same thing even though logically speaking you might be fooled into thinking they should be opposites the way their etymology implies is a good example.

Though of course they're not exact opposites and that's the trick to it: language just doesn't give a shit about being logical, it only cares about communication succeeding, so in the above example the reason these words are this way has nothing to do with somebody sitting down and consciously deciding to use 'up' and 'down' as metaphors, it's that at different points in time ("I'm up for this" created in the 19th century; "I'm down"=jazz slang from the 1930s) different people felt the need to casually communicate their consent to an activity in a casual, quick manner that worked well. And notably: there is NO need for an equally structured opposite in this kind of language situation -- if you want to decline an invitation you do not want to be that casual: the challenge is a different one here, as you want to avoid offending the person who invited you, so you explain why you can't make it, or you quickly apologize, or you tell them you're busy in vaguer terms. Nobody ever came up with the idea to use "I'm down for this" to mean declining an invitation, because the quick, flippant way this would be structured as isn't really suitable for the task.

To answer your question, I do in fact think about things like this very often^^

#never heard the word downcome before actually#mass ask sending anon#feel free to always ask about linguistics anon-chan^^#I am always up to ramble about languages

1 note

·

View note

Text

A Teach Yourself Linguistics Linkfest from Mutual Intelligibility

Looking to teach yourself linguistics? Mutual Intelligibility was a year-long project to help curate free linguistics resources online for people who are trying to teach or learn linguistics, and now all of its posts are collected here for you.

Crash Course Linguistics

A structured introduction to linguistics. Each post contains a 10-12 minute video from Crash Course Linguistics, plus supporting resources on the same topic including exercises with answer keys.

Week 0 - Preview

Week 1 - Introduction

Week 2 - Morphology

Week 3 - Morphosyntax

Week 4 - Syntax

Week 5 - Semantics

Week 6 - Pragmatics

Week 7 - Sociolinguistics

Week 8 - Phonetics, Consonants

Week 9 - Phonetics, Vowels

Week 10 - Phonology

Week 11 - Psycholinguistics

Week 12 - Language acquisition

Week 13 - Historical linguistics and language change

Week 14 - Languages around the world

Week 15 - Computational linguistics

Week 16 - Writing systems

Resource Guides

Longer, more comprehensive guides to a few common intro linguistics topics.

Introduction to IPA Consonants - Resource Guide 1

Introduction to IPA Vowels - Resource Guide 2

Introduction to Morphology - Resource Guide 3

Introduction to Constituency - Resource Guide 4

Introduction to World Englishes - Resource Guide 5

Introduction to Languages around the World - Resource Guide 6

3 Links Posts

Quick highlights of three relevant links about a specific topic, with a short description for each.

3 Links about Linguistics Teaching

3 Links for Second Year Syntax Videos

3 Links for Second Year Phonology

3 Links for Natural Language Processing

3 Links for Semantics and Pragmatics

3 Links for Sociolinguistics

3 Links for Second Year Psycholinguistics

3 Links for Field Methods

3 Links for Articulatory Phonetics

3 Links for Writing Systems

3 Links for Gesture Studies

3 Links for Linguistics Communication (lingcomm)

3 Links for Evidentiality

3 Links for Linguistic Discrimination

3 Links for Linguistics Careers Outside Academia

3 Links for Schwa

3 Links for the Linguistics of Emoji

3 Links for Proto-Indo-European

3 Links for Second Language Acquisition

3 Links for Zero Morphemes

3 Links for Internet Linguistics

3 Links for Language Revitalization

3 Links for Online Teaching

#linguistics#crash course#crash course linguistics#linkpost#roundup#linkfest#mutual intelligibility newsletter#3 links#resource guides#protolinguist#teach yourself linguistics#self-teaching linguistics

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Mutual Intelligibility: Directory of all posts

This post was originally published on the Mutual Intelligibility mailing list.

Mutual Intelligibility has been a year-long project to curate online linguistics resources. As teaching and learning shifted rapidly to internet-based mediums in early 2020, we wanted to help guide instructors and learners through some of the amazing linguistics content that’s already freely available online.

Below is a full collection of all of the posts that featured on Mutual Intelligibility. Our thanks to everyone who created the resources that we featured, to Liz McCullough for her editorial work, and to the Lingthusiasm patrons who helped us fund this project.

We currently do not have plans to continue with regular Mutual Intelligibility newsletters, but we will keep these existing posts publically available and you can keep an eye out for the occasional future email as we have relevant plans to share. For a more regular correspondence, you can get a monthly email when there’s a new Lingthusiasm episode (including supplementary links on that topic), by signing up at lingthusiasm.substack.com.

Crash Course

To accompany the 16 weeks of 10-12 minute introductory videos on Crash Course Linguistics, we created a newsletter with supporting resources and related activity/activities, curated by Liz McCullough. The activities are mostly from the International Linguistics Olympiad and various national olympiads, which are a huge treasure trove of linguistics puzzle sets.

Week 0 - Preview

Week 1 - Introduction

Week 2 - Morphology

Week 3 - Morphosyntax

Week 4 - Syntax

Week 5 - Semantics

Week 6 - Pragmatics

Week 7 - Sociolinguistics

Week 8 - Phonetics, Consonants

Week 9 - Phonetics, Vowels

Week 10 - Phonology

Week 11 - Psycholinguistics

Week 12 - Language acquisition

Week 13 - Historical linguistics and language change

Week 14 - Languages around the world

Week 15 - Computational linguistics

Week 16 - Writing systems

Resource Guides

These six Resource Guides provide a comprehensive lesson plan (like a textbook’s supplementary material but entirely online), and were compiled with the assistance of Kate Whitcomb. They are also available in PDF and Doc format.

Introduction to IPA Consonants - Resource Guide 1

Introduction to IPA Vowels - Resource Guide 2

Introduction to Morphology - Resource Guide 3

Introduction to Constituency - Resource Guide 4

Introduction to World Englishes - Resource Guide 5

Introduction to Linguistic Diversity - Resource Guide 6

3 Links Posts

3 Links posts are quick highlights lists of three relevant links about a specific topic, with a short description for each of the three resources. We produced twenty-three 3 Links posts in 2020, most of which were edited by Liz McCullough, with other contributors noted on the posts themselves.

3 Links about Linguistics Teaching

3 Links for Second Year Syntax Videos

3 Links for Second Year Phonology

3 Links for Natural Language Processing

3 Links for Semantics and Pragmatics

3 Links for Sociolinguistics

3 Links for Second Year Psycholinguistics

3 Links for Field Methods

3 Links for Articulatory Phonetics

3 Links for Writing Systems

3 Links for Gesture Studies

3 Links for Linguistics Communication (lingcomm)

3 Links for Evidentiality

3 Links for Linguistic Discrimination

3 Links for Linguistics Careers Outside Academia

3 Links for Schwa

3 Links for the Linguistics of Emoji

3 Links for Proto-Indo-European

3 Links for Second Language Acquisition

3 Links for Zero Morphemes

3 Links for Internet Linguistics

3 Links for Language Revitalization

3 Links for Online Teaching

Thanks to everyone who has been following us and sending in questions and links over the past year. It’s been our privilege to help make a rough year somewhat easier for you.

Lauren, Gretchen, Liz, and the rest of the Mutual Intelligibility team

About Mutual Intelligibility

Mutual Intelligibility is a project to connect linguistics instructors with online resources, especially as so much teaching is shifting quickly online due to current events. It's produced by Lauren Gawne and Gretchen McCulloch, with the support of our patrons on Lingthusiasm. Our editor is Liz McCullough.

Mutual Intelligibility posts will always remain available free, but if you have a stable income and find that they’re reducing your stress and saving you time, we're able to fund these because of the Lingthusiasm Patreon and your contributions there.

If you have other comments, suggestions, or ideas of ways to help, please email [email protected].

#mutual intelligibility#linguistics resources#linguistics#languages#teaching#learning#online teaching#study online#linguistics online

297 notes

·

View notes

Text

whenever there’s a word, where one of it’s constituent morphemes has an antonym, but the word with the antonym instead is not a word; well that’s a whole post right there

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

“First, I take the position that all language universals are implicational universals. Only under that assumption can one avoid arbitrary decisions as to what will count as a language. Most work on language universals has systematically ignored child language, written language, sign language, non-native language (Roman Jakobson’s English, etc.), and the language of aphasics and schizophrenics. For example, linguists happily accept the claim that all languages have nasal consonants even though they are perfectly aware of languages that do not, for example, American Sign Language. It is of course reasonable for linguists to ignore ASL here: the universal relates to the vocal medium of spoken languages. However, the irrelevance of ASL to some language universals does not make it irrelevant to all discussion of language universals – it clearly is relevant to discussions of universals of constituent order or of semantic distinctions in the lexicon. If ‘language’ is understood broadly and universals are taken to be implicational, exclusion of any types of language from the domains of universals must be for cause: the antecedent of the implicational universal must give the grounds on which the particular varieties of language are to be excluded (for example, ‘If the medium of expression of a language is vocal, it will have nasal consonants’, excludes ASL by virtue of its medium of expression being nonvocal), and the linguist must attempt to state universals in their greatest generality, that is by specifying as narrowly as possible the conditions that would remove a variety of language from the applicability of the putative universal.

Second, I wish to dissociate myself from an assumption that is so popular among linguists that it is difficult to find anyone who disputes it, namely the assumption that people who talk the same have the same linguistic competence. I have recently been advocating (McCawley 1976a; 1977a) a conception of language acquisition in which many details of acquisition are random or are influenced by ephemeral details of linguistic experience. Such a scheme for language acquisition need not lead to gross inhomogeneity in a linguistic community, since there is ample opportunity for revision of learning that has made the speaker grossly divergent from his neighbors. Moreover, it is easy to think of alternative linguistic rules and underlying forms that yield exactly the same well-formedness data and exactly the same pairings of meaning and expression; indeed, linguists are perpetually arguing about such alternative analyses, for example, the analysis in which the English regular plural ending is /iz/ and a rule deletes its vowel under one set of circumstances, versus the analysis in which the ending is /z/ and a rule inserts a vowel under other circumstances. Maybe for some people plurals work the one way and for other people the other way. The assumption that all normal adult members of a linguistic community have the same internalized analysis in such cases is gratuitous. In the rare cases where linguists have looked for interpersonal variation in language, they have generally found it. For example, Haber (1975) reports that speakers who ostensibly form English plurals the same way give a broad range of responses on tasks requiring the formation of plurals of novel words, with each speaker having his own ways of dealing with novel plurals. There is also considerable individual variation in the morphemic relations that speakers of English perceive, as one can readily verify by asking one’s friends whether pulley is related to pull or tinsel to tin.

Third, and closely related to the last point, I claim conscientious objector status in the ongoing war against ‘excessive power’ of grammatical devices. We have all been taught to limit our descriptive devices as tightly as possible, preferably to those that were good enough for our scientific forefathers, since seemingly innocuous devices may turn out to harbor within them the dread Turing machine. It has accordingly become common for linguists to attempt to resolve disputes among competing analyses by drafting sweeping restrictions on grammars so as to give one of the competing analyses a legal monopoly. I will argue below that many proposed language universals have served only to allow linguists to construct cheap arguments for their favorite analyses and that those arguments have given the illusion of significance only because their alleged role in the war effort against ‘excessive power’ has obscured important respects in which they are extremely implausible."

McCawley 1982. "Language universals in linguistic argumentation." from Thirty Million Theories of Grammar.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Khoe-Kwadi: Khwe

Part 3 of my Khoe-Kwadi series: Khwe

Family Overview

Kwadi

Khwe (or Khwedam)

Khwe is a dialect cluster belonging to the Kalahari Khoe subgroup of the Khoe-Kwadi family’s Khoe branch. According to the seminal Khoe classification by Vossen (1997), Khwe is most closely related to Naro and Gǀui-Gǁana, two Kalahari Khoe languages spoken in the Central Kalahari. However, more recent research suggests that Khwe may be closer to the geographically adjacent Kalahari Khoe languages Ts’ixa and Shua.

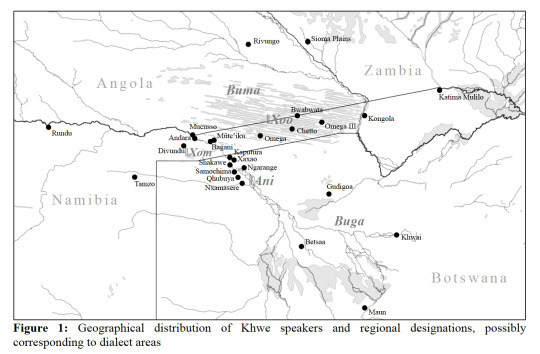

Where is it spoken?

Historically, Khwe speakers dwelt in a vast area reaching from southeastern Angola and western Zambia across the Namibian Caprivi strip into Botswana’s Okavango Delta. Only recent historical events like the civil war in Angola and the Namibian war of independence led to the present-day situation in which the majority of the 7,000–8,000 remaining speakers reside in the Bwabwata National Park of Namibia and along the Okavango panhandle in northwestern Botswana. Work-related migration, resettlement schemes and the establishment of National Parks during the second half of the 20th century further contributed to Khwe speakers abandoning their traditional settlements in favor of bigger villages close to the roadside.

(Map taken from Fehn 2019)

Where does the term “Khwe” come from?

The orthographic spelling “Khwe” derives from the root *khoe ‘person’, which is shared by all Khoe languages and ultimately gave its name to the language family. The Kwadi branch of the Khoe-Kwadi family has *kho ‘person’, suggesting that the -e ending is a suffix, possibly the common gender plural suffix -(ʔ)e still retained in Kwadi. To distinguish the Khwe dialect cluster from the Khoe language family, it was first spelt <Kxoe> by the linguist Oswin Köhler, and later - in agreement with the community - <Khwe>.

Are there dialects of Khwe?

There are two main subgroups within the Khwe cluster: Khwe “proper” and ǁAni. Due to the current sociolinguistic situation which favors dialect leveling, the dialectal diversity within Khwe may be underestimated by most scholars studying the language. Within Khwe “proper”, at least three varieties (ǁXom, ǁXoo and Buga) can be distinguished by phonological, lexical, and possibly also structural isoglosses. It has also been suggested that there are two sub-branches of ǁAni, a western and an eastern variety. We know very little about the Khwe variants spoken in Angola before the war, but some word lists recorded by the South African scholar E.O.J. Westphal suggest that they may have been phonologically and lexically distinct from the well-studied variety now predominant in the West Caprivi (ǁXom).

What does it sound like?

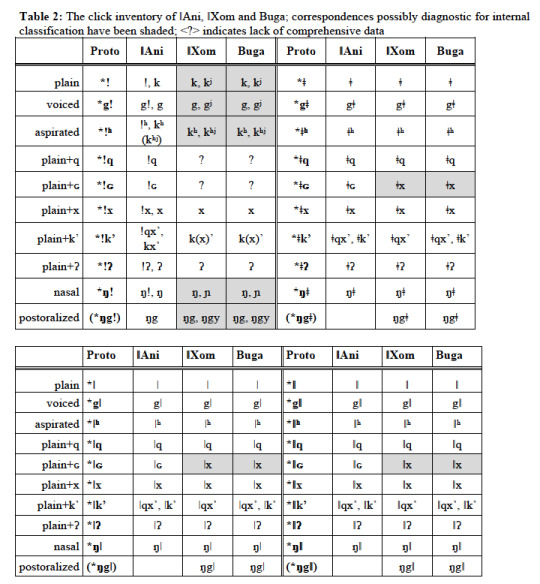

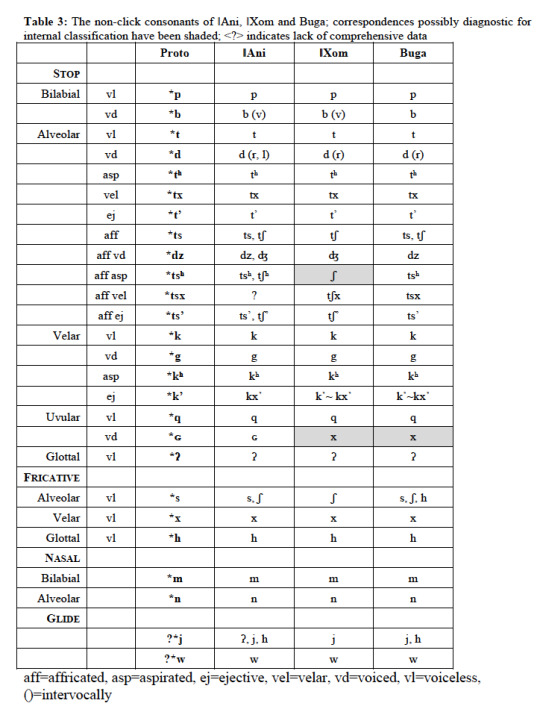

Different Khwe varieties have different phoneme inventories. Here’s a comparison of three varieties for which sufficient data is available (ǁXom, Buga and ǁAni):

(Tables taken from Fehn 2019)

While ǁXom and Buga have lost the alveolar click and replaced it by a velar or palatal stop (safe for some relic forms), ǁAni retains most of its alveolar clicks.

Although the phoneme inventory of Khwe is fairly large from a cross-linguistic perspective, it is smaller than that of Kalahari Khoe languages spoken in and around the Central Kalahari (Gǀui-Gǁana, and Naro), and substantially smaller than the phoneme inventories found in the southern African click-language families Kx’a and Tuu.

Typological features

In Khwe, the basic word order is SOV, but pragmatic considerations allow for both SVO and OSV. The basic constituent order in the noun phrase is head-final. Nouns in Khwe are optionally marked by portmanteau morphemes encoding person, gender and number (PGN). These clitics serve the function of specific articles and attach to about 75% of the language’s noun phrases. Like other Khoe languages, Khwe has a rich suffixing morphology: Derivational suffixes attach to both verbs and nouns, and a subset of the language’s tense-aspect morphemes is linked to the verb stem via a so-called juncture morpheme. Khwe distinguishes between two juncture morphemes triggering different morpho-tonological processes, one for NON-PAST and one for PAST. Khwe has nine suffixes marking tense-aspect, four in the domain of non-past, and five past-tense markers.

The direct object may optionally be marked by the postposition ʔà, which interacts with the argument’s information-structural properties. Oblique (peripheral) participants are obligatorily marked by a set of semantically specified postpositions. Khwe distinguishes between four syntactic verb classes, according to the number of core participants they may take: intransitives, transitives, ditransitives, and S/O-ambitransitives. Predicates may be simple or complex. Complex predicates display semantic features similar to serial verb constructions and involve two or more verbs, which are connected by the juncture morpheme.

Literature (just a small selection - there is lots of published literature on Khwe)

Brenzinger, Matthias. 1998. Moving to survive: Kxoe communities in arid lands. In Mathias Schladt (ed.), Language, identity, and conceptualization among the Khoisan, 321–357. Cologne: Rüdiger Köppe.

Fehn, Anne-Maria. 2019. Phonological and Lexical Variation in the Khwe Dialect Cluster. Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft 169(1): 9–39.

Heine, Bernd. 1999. The ǁAni: Grammatical notes and texts. Cologne.

Kilian-Hatz, Christa. 2003. Khwe Dictionary with a supplement on Khwe place-names of West Caprivi by Matthias Brenzinger (Namibian African Studies, 7). Cologne: Rüdiger Köppe.

Kilian-Hatz, Christa. 2008. A grammar of modern Khwe (Central Khoisan) (Research in Khoisan Studies, 23). Cologne: Rüdiger Köppe.

Köhler, Oswin. 1981. La langue kxoe. In Jean Perrot (ed.), Les langues dans le monde ancien et moderne, première partie: Les langues de l’afrique subsaharienne, 483–555. Paris: Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique.

Schladt, Mathias. 2000. A Multi-Purpose Orthography for Kxoe: Development and challenges. In Herman M. Batibo & Joseph Tsonope (eds.), The State of Khoesan Languages in Botswana, 125–139. Gaborone: Tasalls.

Vossen, Rainer. 1997. Die Khoe-Sprachen: Ein Beitrag zur Erforschung der Sprachgeschichte Afrikas (Research in Khoisan Studies, 12. Vol. 12. Cologne: Rüdiger Köppe.

Vossen, Rainer. 2000. Khoisan languages with a grammatical sketch of ǁAni (Khoe). In P. Zima (ed.), Areal and Genetic Factors in Language Classification and Description: Africa South of the Sahara, 129-145. Munich. Lincom.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Help spread the Lingthusiasm for our second anniversary 🎧💚🌱

November is the second anniversary episode of Lingthusiasm!

This time two years ago, we were a top-secret project that no one had listened to yet, and this time last year we’d just started asking for your anniversary recommendations. It went so well the first time that we’re aiming to thank even more people this year!

Now, we’re a full-fledged podcast that people have described as “incredibly well-researched and fun” and "like I’m listening in on a conversation between two of my most interesting friends.” Here’s a list of episodes so far:

Speaking a single language won’t bring about world peace

Pronouns: little words, big jobs

Arrival of the Linguists: Review of the Alien linguistics film

Inside the Word of the Year vote

Colour words around the world and inside your brain

All the sounds in all the languages - the International Phonetic Alphabet

Kids these days aren’t ruining language

People Who Make Dictionaries - Review of WORD BY WORD by Kory Stamper

The bridge between words and sentences - Constituency

Learning languages linguistically

Layers of meaning - Cooperation, humour, and Gricean maxims

Sounds you can’t hear - Babies, accents, and phonemes

What Does it Mean to Sound Black? Intonation and Identity Interview with Nicole Holliday

Getting into, up for, and down with prepositions

Talking and thinking about time

Learning parts of words - Morphemes and the wug test

Vowel Gymnastics

Translating the untranslatable

Sentences with baggage - Presuppositions

Speaking Canadian and Australian English in a British-American binary

What words sound spiky across languages? Interview with Suzy Styles

This, that and the other thing - determiners

When Nothing Means Something

Making books and tools speak Chatino - Interview with Hilaria Cruz

Every word is a real word

We’re really proud to have brought you a second year of indie linguistics podcasting, including transcripts, and even to have commissioned lingthusiasm art and created two liveshows thanks to our patrons! Here are the bonus episodes that our patrons make possible:

Swear words and pseudo-swears

How to get even more linguistics: our favourite books and other resources

How to sell your linguistics skills to employers

Behind the scenes on doggo linguistics

You and me and octopodes: hypercorrection

ig-Pay atin-Lay and more language play

How to become the go-to person among your friends for language questions: doing linguistics research

So, like, what’s up with, um, discourse markers? Hark, a liveshow!

Is X a sandwich? Solving the word-meaning argument

Liveshow Q and eh

We are all linguistic geniuses - Interview with Daniel Midgley

Creating languages for fun and learning

The grammar of swearing

The poetry of memes

Linguistics grad school advice

Forensic Linguistics

Homophones, homonyms, and homographs

Emoji, Gesture and The International Congress of Linguists

Hyperforeignisms

Bringing up bilingual babies

To celebrate two years of enthusiastic linguistics podcasting, we’re aiming to spread the linguistics enthusiasm even further, and we need your help to get there! Here are some ways you can help:

Share a link to your favourite Lingthusiasm episode so far and say something about what you liked! If you link directly to the episode page on lingthusiasm.com, people can follow your link and listen even if they’re not normally podcast people. Can’t remember what was in each episode? Check out the quotes for memorable excerpts or transcripts for full episode text.

We appreciate all kinds of recs, including social media, blogs, newsletters, fellow podcasts, and recommending directly to a specific person who you think would enjoy fun conversations about language!

Arriving on this page because a friend sent you? (Thanks, friend!) You can click on any of the episode links above to listen right now! The episodes can be listened to in any order, so just go for whatever catches your attention. For mobile listening, you can subscribe in iTunes/Apple Podcasts, SoundCloud, Overcast, Pocket Casts, Stitcher, Google Podcasts, Google Play, Spotify, rss, or wherever else you get your podcasts.

If you didn’t get around to listening to a couple episodes when they came out, or you’ve been following us on social media and haven’t gotten around to listening yet, now is a great time to get caught up!

Write a review wherever you get your podcasts. The more reviews we have, the more that the Mighty Algorithms make us show up to other people browsing. Star ratings are great; star ratings with words beside them are even better. (While you’re there, maybe hit the stars for other podcasts you like too?)

All of our listeners so far have come from word of mouth, and we’ve enjoyed hearing from so many of you how we’ve kept you company while folding laundry, walking the dog, driving to work, jogging, doing dishes, procrastinating on your linguistics papers, and so much more. But there are definitely still people out there who would be totally into making their mundane activities feel like a fascinating dinner party about how language works, they just don’t know it’s an option yet. They need your help to find us!

If you leave us a rec or review in public, we’ll thank you by name or pseudonym on our upcoming special anniversary post, which will live in perpetuity on our website. If you recommend us in private, we won’t know about it, but you can still feel a warm glow of satisfaction (and feel free to tell us about it on social media if you still want to be thanked!).

Stay Lingthusiastic!

506 notes

·

View notes

Text

Erratum! Eliot does recognize the obviative--kind of. From The Indian Grammar Begun, pg. 9:

Yet there seemeth to be one Cadency or Case of the

first Declination of the form Animate, which endeth in oh,

uh, or ah; viz. when an animate Noun followeth a Verb

transitive whose object that he acteth upon is without himself.

For Example: Gen. 1. 16. the last word is anogqsog,

stars. It is an Erratum: it should be anogqsoh;

because it followeth the Verb ayim, He made.

In the modern day we would recognize the obviative ending -ah of animates, indifferent to number. Eliot recognizes this usage in the direct (Theme 1) paradigm of verbs with two third-person arguments--but, it seems, nowhere else. (He gives paradigms for possessives and recognizes that most nouns have to take the suffix /-əm/ in the possessive, but only gives paradigms for inanimates and so passes over the use of the obviative with third-person possessors.)

A good giveaway that Eliot is still operating within the Latinate paradigm is that his tables of endings are not broken up into component parts:

There are morphemes here! But Eliot assumes that Massachusett is essentially fusional and assigns a single massive ending for, say, “preterite optative 1PL > 3SG” (obviously he’s not thinking in those terms, but that’s what’s going on). Even so Latin grammar is not really totally analytical--it’s not difficult to see that amabat is composed of four constituents am-a-ba-t and that each does a particular job (stem, thematic vowel/indicative marker, imperfect marker, third-person singular active marker). On the other hand, it’s...difficult to pin down the meanings of some Algonquian morphemes in terms that Indo-European speakers can understand (think of the theme signs, for example).

(Surely, surely there were descriptions of Basque floating around at the time. The Spanish seemed to have been somewhat better at linguistic description than anyone else was--possibly because they already had some contact with a language whose typology is not unlike that of many languages of the Americas? There’s a history study waiting to be written here--Colonial Linguistic Description and Theory from de las Casas to Boas.)

(wrt the Puritans, something I’m not sure anybody has done--because it’s an absolutely massive text that hasn’t really been digitized--is looking through the Eliot Bible, which was written considerably after (er, wait--was it before?) The Indian Grammar Begun, to figure out the extent to which he had acquired the nuts and bolts of Massachusett up to that point and how much, if at all, native speakers were proofreading him. If, for example, he started consistently obviating animates with third-person possessors, that represents a leap in understanding over The Indian Grammar Begun. Never mind, looks like The Indian Grammar Begun was written after the Bible was published--still!)

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Post #7: Noboru and mother—mother and man—man and sea—sea and Noboru...

The key to synchronization is the same as the key to making sense of things which is the key to composing a larger thing by fashioning smaller things into constituent parts—which makes sense because a thing is made sense of by its context. St Augustine wrote that we "must" distinguish between the "beauty" which belongs to the whole in itself, and the "becomingness" which results from right relation to some other thing, as a part of the body to the whole." De Pulchro et Apto—on the beautiful and the fitting. The key is where something fits: just as a morpheme fits into a word, and a word into a sentence, and a sentence into a conversation and a conversation into the mind.

So really it's like matching dominoes or playing Crazy Eights. Except in the world we've got all these senses that we use to make sense of the world. I'm not claiming it's only sight, smell, hearing, taste and touch but it's definitely at least those. So we've got sight, smell, hearing, taste and touch and something can match something else, connect to it, by sight, smell, hearing, taste and touch. It's like how the face has parts: the sight of something and the smell of something won't actually be alike—although they sure can be associated. There are certainly lots of associations that are powerful: whether they're innate as I think synesthetic effects are said to be (as, perhaps, the bouba/kiki effect is) or whether they seem to have some sort of cultural mapping (how do you feel about the claim that all dogs are boys and all cats are girls?). But the sight, smell, sound, taste and texture of something are fundamentally distinct despite these associations (and the predictions we can make as a result of these associations—"that surface looks rough...").

So when you're construction a synchronization, or a larger thing, or something that fits together—it's about finding ways to match it all up (isn't it satisfying?). Matches or parallels in language can occur in a variety of these fundamentally distinct ways: by means of the reference, or of the form, or of the style. So Eliot can invoke (or should I say evoke? It's hard to tell, because they sound an awful lot alike...),

-so Eliot can invoke Webster ("But keep the wolf far thence: that's foe to men / For with his nails he'll dig them up agen") with the FORM of his own lines: ("Oh keep the Dog far hence, that's friend to men, / Or with his nails he'll dig it up again!"). He invokes Psalm 137 with form too ("By the waters of Leman I sat down and wept...")—tying it to what his poem is describing, and really also to his own life, since he went to recuperate in Switzerland after freaking out at his bank job or whatever.

-Or he can invoke his own earlier work, the stuff involving Sweeney, with the REFERENCE of the words he uses ("The sound of horns and motors which shall bring / Sweeney to Mrs Porter in the spring"). This is also a referential match with the popular song about Mrs Porter and her daughter, which Eliot makes abundantly clear by DUPLICATING (i.e. exactly, at least as far as you can between two TEXTS, since The Waste Land has no melody and though the song has a melody, it doesn't written with the alphabet on paper) the song in a sort of rhetorical unrestrictive relative clause that adds to the substance of the poem ("O the moon shone bright on Mrs. Porter / And on her daughter / They wash their feet in soda water"). In a sense, he's even PRODUCING a match by JUXTAPOSITION (because we tend to assume that two things are associated if they're juxtaposed, and the frequent encounterance of the juxtaposition of two things leads to an association: ie where there's smoke, there's fire... I mean I think a juxtaposition causes an association and here he's wielding it explicitly) with Verlaine, who he duplicates in the next line (Et O ces voix d'enfants, chantant dans la coupole!)

-He can also invoke by STYLE (I'm not sure if this is just a broader/less specific look at form or not): compare the pseudo-free verse that dominates most of "The Burial of the Dead", which the occasional linking rhyme that emphasizes or underscores a connection with the conversation-imitative with about Lil and Albert in "A Game of Chess" or with the ABAB-rhymed/iambic-pentameter-cadenced part of "The Fire Sermon" that Tiresias narrates.

These are all the sorts of keys that the Eliotpilled have used to make sense of The Waste Land. They're checking for matches. Because allusion is done through match. Eliot uses the allusion to enhance and build up the meaning: and the allusion is done by MATCHING what or how he writes to something identifiable in the world.

We see this kind of effect in the real world too. When people flirt, they are said (and it's true, you can observe this, go and try it!) to engage in mirroring or imitation of each other—through body language, but you will also find it through tone or etc etc etc. Because it's literally a way of CONNECTING to kind of come in on the same joke or adjust to speaking the same way (friend groups who all start talking the same way) or whatever. So that's what you do: you have an easy time being IN SYNC with someone or CONNECTING with them if you can get more things MATCHED UP. (Consciously or unconsciously.) You've seen the memes about being stealing personality traits once you've begun hanging out with someone, the warnings that you are the average of your five closest friends? It's all there, it's all there. It's like a jigsaw puzzle: something bigger is made by putting pieces together in a way that they fit, and each piece makes more sense once it's got all the pieces around it.

So pieces sort of get built up in layers over time. It's like taking the structure of a building and remodeling it—some things are kept as is, some things are expanded upon, some things are transformed, some things are replaced. You may even imitate another building you've seen when redoing a certain part of your own building! In this way did Johnson's "32-20 Blues" come from James's "22-20 Blues". It seems to me to factor into how things like jokes and expectations and genres work too. You wonder how it goes with co-option of culture and stuff, just sticking Pagan practices into the clothing of Christianity or whatever.

So I'm not saying it's limited to reference, form, style, whatever—there's probably a million ways, just as there's probably (certainly) a million more senses than sight, smell, hearing taste and touch. But it's all about parallels and matches (because two things match if they're parallel, it's like a Bongard problem, it's like identifying different groups of things, its like when two shapes are congruent or similar in geometry.) Humans love a match, humans have got the pattern recognition, obviously a reason for that. (well I'm not going to claim it's because that's how we act bc I'd guess we act that way bc we're wired about matching and pattern recognition—just how the world works? Same kernel everywhere, you can MAKE SENSE OF and BUILD GREATER THINGS in every part of the world this way—isn't DNA with all the matching strands? Paired and associated amino acids, this and that. And something about electrons and valence.) So I just think it's interesting.

Because every difference means a difference. A change to the form of a linguistic construction necessarily corresponds to a change to in the function (the EFFECTS, oh my god i can feel the effects) of the construction. And form could be lexical, syntactic, intonational, whatever, whatever. Sight, smell, hearing, taste or touch. Like the parts of the face. One of my Russian lit professors once told us about the Symbolists, just talking about infinite webs of associations and that sort of thing. Well, maybe they were onto something.

0 notes

Text

(Mis)Understanding Mandopop… I think I can’t parse!

When I was young and naive, I used to think that as native speakers we automatically have full understanding of our language. Why wouldn’t we, after the long boring infant days (or nights for nocturnal babies) of deciphering meaningful signals from the chaotic and often not-so-meaningful conversations of adults (and other babies)? However, my confidence got crunched when I became a Mandopop (Mandarin popular music) fan, for not only do singers frequently create their own vocabulary, but even the ordinary language fragments also become difficult to grasp. For example, I heard (1) when I was 14.

(1) Ba wo-de xingyun-cao zhongzai ni-de meng-tian.

—-BA I-POSS lucky-grass grow-at you-POSS dream-field

��“Grow my four-leaved clover in your dream field.” (‘Love’ by The Little Tigers)

This is the first time I have ever encountered the two-syllable string meng-tian. It doesn’t exist in my mental dictionary, and without knowing which characters are used to write it, it’s simply impossible to interpret, for each syllable has four possible tones, and each tone further has a number of homophones with different meanings. The chances of picking out the correct tones and combining them into the correct meanings are not very high!

Chinese characters for ‘dream-field’ [1]

The failure to recognize randomly coined words can leave you confused, but the failure to parse a sentence correctly can leave you with a very false interpretation of what the lyrics are saying. I remember wrongly parsing (3) and (4):

(3) a. Mimimama shi wo-de zi-zun. (O = Original)

——-thickly dotted is I-POSS self-esteem

——“Thickly dotted is my self-esteem.” (‘Growth Rings’ by Diamond Zhang)

—-b. Ni mama shuo wo-de zi-sun. (M = Mine)

——your mom say I-POSS son-grandson

—–“Your mom says: ‘my sons and grandsons.’”

Well, I did wonder for a moment how likely my understanding could be correct – it doesn’t sound like a daily scenario after all. But as an open-minded person I decided to accept it, considering that the artistic world can be very dramatic. Google says many others have also misheard “thickly dotted” as “your mom”, and in my honest opinion, the original line doesn’t make much more sense.

(4) a. Ruguo…zai jiao-hui shi neng renzhu-le jidong-de linghun. (O)

——-if…be-at cross-meet time can refrain-ASP excited soul

——“If we could have refrained our excited souls when we met each other.”

(‘The Most Familiar Stranger’ by Elva Hsiao)

—-b. Ruguo…zai jiaohui shi nan-ren zhu-le jidu-de linghun. (M)

——-if…be-at church be male-person dominate-ASP Christ’s soul

——“If it were the man that had dominated Christ’s soul in the church.”

When I realized I had been so wrong, I was both shocked and amazed, because my mind had successfully picked all the wrong tones/meanings and grouped them into wrong constituents, which is just as great an achievement as doing everything correctly! I guess what triggered my mistake is the singer’s vague pronunciation of neng. She pronounced [ɤ] in a quite open way (like [ʌ]). Then I wrongly grouped neng and ren together as nan-ren ‘male-person’, which in turn forced me to analyze zhu as a main verb zhu3 ‘dominate’ (it is an aspectual verb zhu4 in the original lyrics), leading to the subsequent parsing mistakes. How important it is to articulate clearly!

Four tones in Mandarin Chinese [2]

So, a major cause of the wild misunderstandings in Mandopop seems to be the masking of lexical tones and word boundaries by melody and rhythm. There are so many homophonous morphemes in Chinese that tones become a crucial part of lexical information, and there is so little morphological marking that prosodic properties become significant cues for successful parsing. Therefore, when these two sources of information are blurred, we are left quite helpless and can only rely on massive lexicon searching, guessing, and context matching, which work well for frequent items like jiao4hui4 ‘church’ but horribly for unfamiliar or even randomly coined items like jiao1-hui4 ‘cross-meet’ and meng4-tian2 ‘dream-field’.

Luckily, since the Chinese characters don’t rely on pronunciation to convey meaning, a single glance at the lyrics would help us achieve a 100% successful parsing rate in most cases, unless the sentence is inherently ambiguous, as in the following mobile phone commercial. I’m not even sure which reading would be more appreciated by customers!

(5) Mai3 shou3ji1 song4 lao3po2 !

—-buy mobile send as gift wife

—“Intended: buy a mobile phone for your wife!”

—“Alternative: buy a mobile phone and we’ll send you a wife as gift!”

Not being able to efficiently parse what you hear can be tough, but from another perspective it can also be beneficial, because it gives you the interesting experience of imagining all sorts of possible meanings. Some images may be weird, but some may be aesthetically enchanting. I myself have been very satisfied with my misunderstanding of the following lyrics (obviously I’m a fan of Jay Chou).

(6) a. Wo zai deng mo-zhui, huo-yan tunshi wu-ming-bei. (O)

——-I be-at wait magic-pendant fire-flame devour no-name-stele

——“I’m waiting for the magic pendant; the fire is devouring the nameless stele.”

(“Dragon Rider” by Jay Chou)

—-b. Wo zai deng mo zhui, huo-yan tunshi wo ming fei. (M)

——–I be-at wait devil fall fire-flame devour my life fly

——“I’m waiting for the devil‘s fall; the fire is devouring me and my life flows away.”

(7) a. Ju yi-ba yue, shou lan huiyi zenme shui? (O)

——-hold one-handful moon, hand embrace memory how sleep

—–“I hold a handful of moon (from the water); how can I sleep with memory embraced in my hands?”

(“Preface to Orchid Pavilion” by Jay Chou)

—-b. Ju yi ba-yue, shou ran huiyi zenme shui? (M)

——-chrysanthemum already eight-month, hand dye memory how sleep

—–“The chrysanthemums are already August-like; how can I sleep with memory dyed into my hands.”

I listened to both songs when they first came out – both in the 2008 album Capricorn – without having access to the lyrics. So I made the effort to guess what the singer was singing, which is very difficult because of his famous ‘mumbling’ style. I wrote down what I thought I was hearing, and when I finally saw the lyrics, I realized I had written my own songs!

Nowadays I no longer have the time or patience to do lyrics guessing, but the parsing difficulty of Mandopop lyrics hasn’t changed a bit. Recently I’ve been listening to Jay Chou’s 2016 new album Jay Chou’s Bedtime Stories but haven’t bothered reading the lyrics, so maybe it’s time to pick up my old hobby. Let me know if you want to join me or simply want to know more about Mandopop! 🙂

Picture source: [1] http://www.theepochtimes.com/n3/1033631-chinese-character-for-dream-meng-%E5%A4%A2/ http://www.theepochtimes.com/n3/1133160-chinese-character-for-fields-tian-%E7%94%B0/ [2] http://www.kailindesign.com/sitone/

(Mis)Understanding Mandopop… I think I can’t parse! was originally published on CamLangSci

7 notes

·

View notes