#deuteronomic theology

Text

WHY YOUR MORALITY IS MY PROBLEM: modern holdovers from ancient theology

James Dobson, founder of the ultra-conservative Focus on the Family organization, reputedly said of the 2012 Sandy Hook mass shooting, “I think we have turned our back on the Scripture and on God Almighty and I think He has allowed judgment to fall upon us.”

As heartless as that sentiment sounds today when addressing the murder of 20 first-graders (and 6 adults) at an elementary school, it reflects a once-common theology that emerged about four thousand years ago in the ancient near east (ANE*), then bled into the Mediterranean basin and developed an astonishingly long half-life. It’s why some Christians (et al.) are so, so concerned with what their neighbors are doing behind closed doors. Or on their front lawns with all those Pride flags.

In some ways, ANE and Mediterranean religion had a lot in common, being traditional and focused largely on sacrifice/action (orthopraxic). Over time, some orthodoxic religions also arose in that area. So, first, let’s do some quick defining.

Orthopraxic religions focus on what one DOES, not what one believes. Performing the sacrifice correctly, honoring the gods/ancestors appropriately…that’s how one shows piety. Infringing against purity laws or other affronts to the gods (impious actions) can result in expulsion from the community. Fights over correct practice can lead to schism in a community.

Orthodoxic religions focus on what one BELIEVES. Thus, they need some form of authoritative text to determine what IS right belief, resulting in the emergence of a canon (e.g., Zoroastrian Avesta, Jewish Tanakh, Christian New Testament, or Muslim Qur’an). In Orthodoxic religions, wrong beliefs (heresy) can result in expulsion from the community. Fights over correct belief can lead to schism in a community.

(There’s yet a third focus, orthopathic, but that largely doesn’t apply here. “Orthopraxic” can also apply to ethics-based religions, but here, it applies to ritual/cultic behavior.)

Most religions have elements of all three, but it matters where the weight falls. Yes, religions can emphasize two sides of the triangle more heavily, less on the third, but even then, one point will be the chief measurement of devoutness among followers. This also helps us understand why two religions might not understand each other very well sometimes. They’re trying to impose one set of “What religion is for” ideas on another, with entirely different assumptions.

The religions of the ANE and Mediterranean had much in common in terms of the purpose of religion: to maintain the health of a community. This depended on the piety of that communities’ members. Their gods weren’t moral in the modern sense, but could be jealous, fickle, and petty.

Why were they gods then?

Because they were immortal and more powerful.

Yet an important difference between (many) ANE and Mediterranean religions were the concepts of sin and “mesharum” (divine justice/equilibrium). If the latter existed (sorta) in Mediterranean society, “sin” really didn’t. Impiety differs as it can include ritual matters too. So, if murder (especially kin murder) created uncleanness anywhere and is a moral/civil matter, menstruation and sex also created uncleanness, but were not moral/civil matters defined as “bad.” So “unclean” ≠ “sin.”

To be unclean is a matter of cultic purity, different from moral purity. Yes, ANE religions also had ritual uncleanness, to be sure. And yes, some things that make one unclean also have intimations of “badness” without being so extreme as murdering someone. Yet I want to underscore the difference because it’s very real and too often ignored/misunderstood/unfairly conflated.

Many Mediterranean religions did not have “sin,” just unclean and impious. MORAL/ETHICAL matters were dictated by civil law and later, philosophic discussion. Not religion. Yet in the ANE, moral infractions were affronts to mesharum (divine order) and were therefore a religious matter. This oversimplifies, but smash-and-grab works for now. We find actions (like iconoclasm) in the ANE that didn’t often apply in the Mediterranean. (Iconoclasm is the deliberate theft, or in extreme cases, destruction of religious icons or structures.)

Yet what both groups shared was a sense that the gods had, well, “bad aim.” If people in a community were impious and/or sinful, that might draw the ire of the gods. Plagues were often seen as divine retribution for the impiety and/or sin of one or more members of that community, but not necessarily all of them. This led to the exile of impious individuals, as well as the ANE “scapegoat” ritual, et al. (If you’re familiar with the plot of the Iliad, Apollo punished the entire Greek army for the impious actions of Agamemnon.)

I could DIE from your impiety/sin committed in my town/community.

That makes your morality my business.

In addition, especially in the ANE, war on earth was believed to reflect war in heaven. Gods had cities and peoples, not the other way around. They chose you, you didn’t god-shop—hence Israel as a “chosen people.” Well, yeah, pretty much every ethnic group was chosen by some god(s). But as a result, if your side lost in a war, then—theoretically—your gods were weaker. Maybe you should go over and start worshiping their gods. Yet that didn’t sit well with most groups, so by the Middle/Late Bronze Age, we see an emerging idea that my god isn’t “weaker” than yours, rather my general “set forth without the gods’ consent,” or my god permitted the other god(s) to win for whatever reason…usually due to sin or a lack of piety among his (or her) people. Of course we find this in the prophetic literature of the Hebrew Bible, but it’s in a lot of other ANE literature too. Nabû or Marduk didn’t lose, they “went to live with” Ashur for however many years—although the winning side will portray the victory as Nabû and Marduk traveling to Nineveh to bow before (e.g., submit to) Assur.

Again, this is simplified, but we don’t see this sort of language used in Greece where Hera would bow to Athena because the city-state of Athens defeated Argos, even if, as promachos (foremost in battle), Athena might be expected to win in any conflict between the two (as in Euripides’ Children of Herakles). Hera is still queen of the gods, and—even more—these are shared deities. We also don’t see it because notions of “sin” don’t apply and only a handful of wars were ever called “sacred”—all of them concerning Delphi and cultic purity. At least one of those is mythical, the second probably didn’t happen, and the third (which certainly did happen) was labeled “sacred” only by one side. Greek gods just weren’t seen to uphold justice in the same way. Roman gods were more concerned with such things, but still not as we find in the ANE.

Ergo, the ANE faced the problem of theodicy: if god/the gods are good/just, why does tragedy happen?

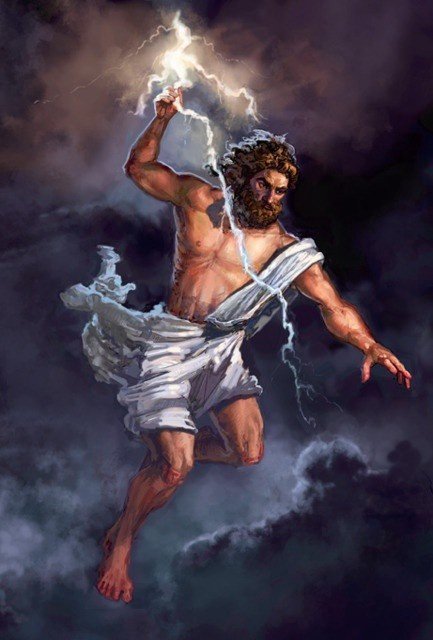

Early explanations for tragedy were simple: those who suffer must have earned their suffering, sometimes referred to as Deuteronomic Theology: “good things happen to good people”/“bad things happen to bad people” (and maybe their neighbors too, by chance).

Pushback against this notion emerged around the same time a more nuanced view of loss in war emerged. People began to ask the corollary: “Why do bad things happen to good people?”

The (c. 1700 BCE) Mesopotamian Ludlul bēl nēmeqi (The Poem of the Righteous Sufferer) attempted an answer. About a thousand years later (600s-500s BCE), the Jewish Book of Job took it on as well. In both, the protagonist asks, “Why does Marduk/Yahweh punish me when I’ve been a faithful servant?” Both protagonists were previously wealthy/powerful, which was seen as divine approval. Losing that wealth/health suggested they had offended their god (and are being punished). Yet each one claims he did not sin—so why?

The answer in both works is similar: there’s not really an answer. Marduk restores Šubši-mašrâ-Šakkan, who ends the poem with a prayer of thanksgiving. Job has a chat with Yahweh, who essentially tells him, “You’re a measly mortal, don’t question me.”

The KEY element in both, however, isn’t the answer, but the assertion that a good person can suffer. They didn’t earn it; it just happened. They remained good and, eventually, their god restored them to their prior station, and then some.

Ergo, if you’re suffering, just be patient. Don’t curse God and die. (As Job is advised to do.)

Today, we may find such an answer wanting but need to recognize it for an advancement on the theology of tragedy.

Some, however, get stuck in these time-locked answers because they can’t allow their religion to grow. Or rather, they can’t acknowledge that their religion/theology evolves over time, because if it evolves, it wasn’t perfect from the beginning. And that challenges their understanding of their god.

Yet the real fly in the ointment is the notion of a perfect and infallible canon.

This brings me back around to what a canon is. It just means “an authoritative text,” but how that text is understood has nuances. INSPIRED ≠ INFALLIBLE. Most all followers of a canonical text believe it’s inspired by God, but not all (or even most) believe it’s infallible. (Islam is its own category here, note.) That creates some problematic GRAYS.

If it’s only inspired, written by humans with human foibles and history-locked understandings, interpreting it becomes complicated and can lead to disagreements. Taking a literalist view sweeps away the messiness. “God said it; I believe it; that settles it!” Black-and-white.

Those who believe in Biblical literalism/inerrancy (which includes a good chunk of conservative Christian Evangelicals and all Fundamentalists**) will argue ALL the Bible is true. If it’s written by God, it must be perfect from the get-go. Thus, a clash is created between simpler versus more nuanced views: Deuteronomy vs. Job. If an earlier view must be as true as any later one, that reduces everything to the most elementary version. It can’t evolve/grow up, yielding what feels to most like a very archaic (and often harsh) worldview.

In any case, both the traditional orthopraxic and orthodoxic religions of the ANE/Med Basin believed God/gods punished people who offended them. AND these punishments might “spill over” onto family and neighbors.

Ancient divine collateral damage.

Ironically, this is WHY early Christians were prosecuted by the pagan (e.g., traditional) Roman and Greek religious establishments. Christian failure to participate in common civic religious cult could earn divine ire. For their first two/two-and-a-half centuries, Christianity was labeled a religio illicta (illegal religion)—in part for “failure to play well with others.” E.g., make sacrifices to the appropriate Greco-Roman deities. Thus, when disaster struck, a scapegoat was sought. Those antisocial Christians are to blame! They don’t sacrifice to the gods and so, offended XXX god, who is now punishing ALL of us with YYY.

Classic ancient religious thinking, but it’s one reason I find current conservative Christian opposition to Teh Gays, trans folks, etc., enormously ironic. The persecuted have become the persecuting.

I want to emphasize that large sub-groups of Jews, Christians, and Muslims have evolved past such theologies. Yet others have not and stubbornly cling to ancient mindsets. That’s why they argue the mere presence of LGBTQI+ people will bring down the wrath of God on ALL.

Talk of “grooming” and “protecting children” is just an attempt to make palatable a belief they know won’t fly with most people, who they consider deluded by The World (e.g., the devil). Trickery is therefore required. As they’re deeply afraid themselves, they understand fear and use it to motivate others. Many are perfectly happy to make their beds with “unbelievers” long enough to get their agendas passed. God will forgive them.

This, too, is rooted in ancient ideas (discussed above) whereby a people’s own god might employ the enemy to punish them (or others). Thus, a sinful person can be utilized on the way to righteous ends because the victory of God wipes away all else. Using the enemy to effect God’s will just proves that God is in final charge of everything after all. It’s the ultimate PWN.

I hope this helps to explain where these ideas come from, how they originally emerged, and why a subgroup of people still cling to them.

————-

* While Egypt influenced the ANE, as well as Greece and Rome, and is often shoehorned into the ANE, I consider Egypt as NE Africa. It deserves to be treated on its own, or in relation to neighbors such as Kush.

** Fundamentalists and Evangelicals tend to be equated but are not the same. Also, not all Evangelicals are conservatives (although all Fundamentalists are, by definition). Enormous variation exists between Christian denominations, which range from ultra-conservative to (surprise!) ultra-liberal. There is as much of a hard Christian Left as there is a hard Christian Right. We just tend to hear far less about them.

#iconoclasm#mesharum#deuteronomic theology#book of job#poem of the righteous sufferer#ancient theology of tragedy#theodicy#ANE theology#ancient Mediterranean theology#Classics#ancient near east#ancient religion

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Choices Have Consequences: Behar-Bechukotai

Image: An Antarctic glacier calves into the surrounding sea, as even the coldest places in the world warm and cause the ocean to rise. Image under copyright.

Parashat Bechukotai records blessings and curses for keeping or breaking the commandments. At first blush this is oversimplified Deuteronomic theology: “Be good, and good things will happen. Be bad, and you will be sorry.” This theology…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

The sins of the father are the sins of the son

Some people, when confronted with this truth choose to reject God rather than accept Scripture. In fact, it is so difficult to accept the truth of this verse that many would prefer to set it aside altogether. And I have to tell you, if it were not for Jesus Christ in my life, a full understanding of this verse alone would lead me to complete and total despair. You stagger beneath the implications and are crushed by its weight. When you truly ponder its meaning, the enormity of this truth becomes unbearable.

It means that the sins you commit today can directly impact your children, your grand-children, and even your great-grandchildren. The verse is directed to parents, not just fathers. God punishes the children for the sin of the fathers to the third and the fourth generation. But as a parent, no verse scares me more than Exodus 20:5. The book of Revelation paints terrifying images of the end times. For example, the Bible contains many sobering passages dealing with judgment and eternal punishment. Not that there aren’t other frightening passages in the Bible. It was too much to try and cover both idolatry and generational sin all in one message, so I promised to treat this portion of the verse in more detail this week.Įxodus 20:5 is perhaps the most frightening verse of Scripture I know. We looked at verse 5 in its context of idolatry last week, but this verse also raises the problem of generational sin. INTRODUCTION: Our message series is “The Ten Commandments for Today.” Last week we looked at the second commandment, which has to do with idolatry, and right in the middle of the commandment on idolatry we encountered verse 5:Įxodus 20:5 – “You shall not bow down to them or worship them for I, the LORD your God, am a jealous God, punishing the children for the sin of the fathers to the third and fourth generation of those who hate me.” (NIV) At core these differences are a reflection of the changing worldview and beliefs of the 70+ authors who wrote the texts of the Bible which span a 1,000 years.Click here for more messages on The Ten Commandments.Ĭlick here to return to the Sermons page. Although this particular verse may have been created to counter any idea that capital offenses could be ransomed or payed for by another, it nevertheless stipulates against the idea of hereditary guilt, which seems to have been the normative view in many of the Bible’s texts.įinally, this contradiction can be extended into the New Testament, where much of the literature also talks about an individual’s responsibility for his own sins. They shall each be put to death through his own sin” (Deut 24:16).

More explicitly, another Deuteronomic scribe writes the following: “Fathers shall not be put to death for sons, and sons shall not be put to death for fathers. Yet other textual sources negate this theology of inherited sin, or at any rate draw it into question, such as we find in Jeremiah 31:29-30 and Ezekiel 18:2-4.Īfter explaining theologically the fall of Jerusalem on account of the sins of the fathers, Jer 31:29-30 imagines an ideal restitution wherein “all shall die for their own sins”-rather than nations falling for the sins of their fathers is the point. It was also cited to provide the theological response as to why Jerusalem fell (Lam 5:7), and it permeates the book of Daniel, with its repetitive refrain, “the sins of our fathers.” This theology of inherited sin is duplicated in the Deuteronomic version of the Ten Commandments (Deut 5:9), and is prominent throughout the Deuteronomic History. The notion of hereditary guilt runs throughout the Bible and was a common characteristic of most ancient societies.Įxodus 20:5, for example, claims from the mouth of Yahweh himself that he is a jealous god, “reckoning fathers’ sins upon sons, on the third and on the fourth generation.”

0 notes

Text

The Unity of the Canon in the Law on the Central Sanctuary and Altars

A standard liberal critical argument is as follows: "The Priestly Source is emphatic: sacrifices can only take place in the one place that God chooses (i.e. the temple in Jerusalem). Yet, throughout the Hebrew Bible, we see examples of seemingly lawful sacrifices taking place outside of the tabernacle or temple after the giving of the Law. Samuel sacrifices at Mizpah (1 Samuel 7), Elijah sacrifices on Mount Carmel (1 Kings 18)." How would you respond?

Thanks for your question- this is indeed one of the foundational assumptions of the conventional liberal-critical understanding of the history of the people of Israel and of the Sacred Writings. As such, it is an excellent case study of the ways in which liberal biblical criticism obscures the authentic sense of the inspired text on account of its use of interpretive shortcuts when facing a text which suggests the unexpected or inexplicable. If the Christian doctrine of Scripture is correct, such unexpected or confusing texts are actually opportunities, whose integration into one’s biblical theology will correct unseen misunderstandings and provide new insight into the faith.

For those unfamiliar, in Deuteronomy 12 we are told that God will set His Name at a special place of His choice. It is at this place that the people of Israel are to gather to offer sacrifice and to celebrate the Passover, Weeks (Pentecost), and Tabernacles (Booths).Throughout the history of the Kingdoms of Israel and Judah, the people worship at “high places” or independent cult sites found on hills throughout the land. This persists until the reforms of Kings Hezekiah and later Josiah, both of whom seek to remove the high places and establish the centrality of Israel’s liturgical cult at Jerusalem. It is important to distinguish worship at the high places from rank idolatry. Usually, the people worshiped the one God of Israel at these cult sites rather than pagan gods. In other words, it is a violation of the Second Word (which not only requires worship of the true God but worship of Him in the manner He has commanded) instead of the First Word.

However, the orthodox view in biblical criticism is that the requirement for a central sanctuary is a late innovation which was developed in order to increase the wealth of the priestly class in Jerusalem. One does not need to be a genius to see the influence of the Puritan and then liberal Protestant prejudice against “priestcraft” or an ecclesiastical hierarchy. It is merely the old cliche that priests are simply out for your money. This does not prove it historically wrong but it does set it in its context.

Concerning your original question- Deuteronomy is generally considered to represent a largely self-contained source called “D” whereas “P” represents much of Genesis-Numbers, especially the first half of Leviticus (the latter half tends to be attributed to the so-called “H” author). Deuteronomy is supposed to be a forgery of the priests of King Josiah, though in some cases scholars place the forgery in the reign of King Hezekiah. Unfortunately for such critics, the literary form of the Deuteronomic covenant clearly reflects the more ancient form prevalent among the early Hittites and Egyptians (I believe this form belongs to a tradition coming from God’s revelation to Adam through Noah) instead of the later Assyrian form from which it is allegedly derived. This is a very serious problem which has not been adequately dealt with or even addressed. This case is made by Egyptologist Kenneth Kitchen in his enormous survey of the literary tradition of Near Eastern and Egyptian treaties.

Before addressing the substantial point of your question, I wish to point out the classic paradox of biblical criticism as it is manifest in this case. On the one hand, the texts are supposed to be in such obvious contradiction that the only explanation is that they are an ad hoc collection of texts which themselves are a pastiche of various different hypothetical sources in contradiction. But on the other hand, we are invited to believe that the hand of the redactor knit these texts together into a single scroll- which were then transmitted as a corpus by the tradition of the Jewish people. The redactor is alleged to have harmonized the disparate sources and to have edited his texts in order to create a single literary unit. Moreover, when features of one alleged source emerge in a text alleged to be in a different source, the conventional biblical critic again summons the redactor as an explanation. And so we are to believe that the texts are plainly distinct, except when they are not. We must believe that the redactor created a literary unity, except when he chose to permit obvious contradictions.

In this case, the contradiction is so obvious that one wonders how it could have possibly been missed. This is especially so in the sacrifice on Mt. Carmel. Kings is supposed to be a part of the “Deuteronomistic history” whose central purpose is to exalt the reforms of Josiah and explain the exile by the failure to centralize Israel’s sacrificial liturgy. So what in the world is a major sacrifice on Mt. Carmel doing at the heart of the book’s narrative? A major theme of the Book of Kings is the failure of the kings to obey the words of God as communicated through the prophets. The prophetic ministry in the life of Israel manifests the preeminence of divine action in the nation. The prophets are called to a charismatic ministry whose authorization comes from the divine call. Not being from a specific family or deriving their legitimacy from their line of descent, the work of the prophets cannot be controlled or stamped out by the kings of Israel and Judah. No matter how hard they try, those rulers who seek to dethrone the Lord of Hosts from the kingship of Israel and Judah are unable to do so on account of the intrinsically unpredictable institution of prophecy. The literary core of Kings is in the extended narratives describing the ministries of the Prophets Elijah and Elisha.

Christ our Lord, describing the person born of the Holy Spirit, likens them to the wind which "blows where it wishes." As Solomon declares in Ecclesiastes, it is the sovereign Creator alone who can shepherd the wind and govern all things with righteousness. Mankind cannot force the future into his preferred mode. Thus, men must respond in faith to the will of God and recognize that He will bring out of their work everything He intends do unto a good and wise purpose. The prophet is made such by the indwelling of the Holy Spirit. In the order of the cherubic faces, the prophetic face is the Eagle (priestly being the Bull and kingly being the Lion) and in the anointing of an Israelite in the priesthood, the ear, hand, and foot is anointed. The foot is associated with the prophetic. All of this establishes prophets as they who are in motion, who cannot be seized or controlled, who, with the eagle riding upon the wind, fly from place to place by the will of God. Consider how Elijah escapes again and again from the persecutions of Ahab and Jezebel. Consider how he is taken up into the heavens by the Spirit. And Elisha likewise is constantly on the move. He goes even to the nations of the world and anoints Hazael as king of Syria. The travel and motion of the prophet stands as a corrective to the attempts of the kingdoms of Judah and Israel to control their history by their own power and to fix a given political order in place without possibility of change. From the times of Elijah and Elisha, the prophets begin to blow among the nations. Jonah travels to Nineveh soon afterwards. Many of the writing prophets (writing prophets arise at this time in covenant history) communicate oracles to the nations and their kings which they must have sent to the nations, being specifically addressed to the nations and warning of punishment if they did not obey.

The primacy of the prophetic is key in the consideration of this issue, and we will return to it later. For now, I simply want to point out the absurdity of positing that the very "Deuteronomist" who was absolutely committed to the total centralization of sacrificial worship in Jerusalem also placed the construction of a non-Jerusalemite altar in the literary center of his text. Other texts describing Elisha describe him as a kind of living temple of the Spirit. For elaboration on this point, see Peter Leithart's remarkable commentary on Kings. Because of the above, the alleged contradiction is prima facie extremely unlikely.

The manifest nature of the alleged contradiction suggests that what we have encountered is not an obvious contradiction but a failure to properly interpret the teaching of Deuteronomy. So let us consider its actual content.

First, does Deuteronomy 12 refer to the city of Jerusalem in referring to the place where God will make His Name dwell? This is assumed to be the case, and the lack of a named reference to the city is explained by the desire of the forger to avoid anachronism by identifying a city which would only come to prominence several centuries after the time of Moses. But if the forger was so concerned to avoid references to later institutions, why does he refer to the institution of the monarchy in Deuteronomy 17? Such makes no sense. The fact that biblical critics believe Deuteronomy 12 to be a prophetic reference to the building of the temple of Jerusalem reflects their deep lack of care in interpreting the text.

The Book of Joshua is suffused with the language and theological emphases of Deuteronomy. Yet Joshua 8 describes the construction of a cult site on Mt. Ebal as the ark of the covenant is processed before them. Later, in Joshua 24, there is a covenant renewal in the presence of the sanctuary at Shechem. If the heart of Deuteronomy were the centralization of worship in the city of Jerusalem, why does the first book in the “deuteronomistic history” refer directly to liturgical worship at sites other than Jerusalem? The answer to this question lies in the point that Deuteronomy 12 is not about Jerusalem. It is simply about the principle of a central sanctuary for Israel. The actual site of the sanctuary moved around. Throughout much of the period of the judges the cult site is focused on Shiloh. A passage from Jeremiah actually makes note of this directly:

(Jeremiah 7:10-12) and then come and stand before me in this house, which is called by my name, and say, ‘We are delivered!’–only to go on doing all these abominations? Has this house, which is called by my name, become a den of robbers in your eyes? Behold, I myself have seen it, declares the Lord. Go now to my place that was in Shiloh, where I made my name dwell at first, and see what I did to it because of the evil of my people Israel.

The desolation of Shiloh in 1 Samuel 4 is here cited by the Lord as a paradigm for the desolation of the Temple of Jerusalem. In Kings, the prophet-historian Jeremiah describes the fall of the Temple and sack of Jerusalem in language drawn from the catastrophe of the battle of Aphek. The sons of Zedekiah are killed like the sons of Eli. And as Eli became blind at the end of his life, so also is King Zedekiah blinded as punishment. The point is that Deuteronomy 12 has nothing to do with a retroactive attempt to justify the centrality of Jerusalem. It is about the principle of one central sanctuary. That sanctuary can move from place to place throughout history.

Second, we need to consider whether Deuteronomy actually prohibited any and all sacrifice except that performed at the central sanctuary. That is, does "central sanctuary" mean "only sanctuary"? Surprisingly, there is evidence even from the Second Temple period that many Jews did not believe so. After the return from Babylon, we know from the historical record that there were at least four functioning Jewish temples: Jerusalem, Elephantine, Leontopolis, and Tel-Arad. The temples of Leontopolis and Elephantine are particuarly interesting. Concerning the former, it was presided over by the exiled high priestly line descended from Zadok, in fidelity to the biblical requirements concerning the bloodline of the high priests. Moreover, there are later Jewish texts- written after AD 70, which considered the Leontopolis Temple to be legitimate. That they are written after AD 70 is especially significant, for we know that Judaism did not set up alternative temples or cult sites when the Temple was destroyed. We would expect, then, for a complete rejection of the legitimacy of any temple not at Jerusalem. That we actually find a diversity of opinions is strong evidence that many within Judaism during the time of the Second Temple believed that Deuteronomy 12 was not a complete prohibition on all altars except that of the central sanctuary. The temple at Elephantine, Egypt is even more interesting. Scholars have recovered an actual document at Elephantine authorizing the construction of the Elephantine Temple. The author of this text was the High Priest of the Temple of Jerusalem. This is extremely telling, for if any group within Judaism can be expected to reject altogether any cult sites except in Jerusalem, it would be, the priesthood of that one Temple. And yet we find that the High Priest of Jerusalem not only tolerated, but authorized the construction of this cult site.

These witnesses are sufficiently late that it cannot be seriously argued that the canonical authority of Deuteronomy was in doubt among any sect of Judaism at this point in time, even if one holds that the concept of canon was a late development, which I do not The historical evidence tells us that the living memory of the divine commandments concerning the worship of Israel did not include an absolute prohibition on altars or even temples outside of the central sanctuary. Nor is it likely that this constitutes a reversion to the old sin of worshiping at the high places. Just as rank idolatry became increasingly rare after the coming of the Kingdom transformed the tribal confederation of the period of the judges, so also the sin of worshiping according to one's preference and not God's became rare to nonexistent after the return from Babylon. Indeed, the prophets of this period never mention worship at high places.

Third, let us consider the actual theology of the central sanctuary. All of the above constitutes powerful circumstantial evidence for an alternative approach to Deuteronomy 12, but it remains for us to acually construct such an interpretive framework. What is the canonical and theological context for the legislation concerning a central sanctuary? Biblical critics, in assuming that the text is merely an arbitrary way to justify a reform invented for political ends, have missed the profound theology of Deuteronomy and the place of the central sanctuary in the history of God's work in the world. After the creation of the world, God instructs the human family to "subdue" or "conquer" the world, exercising dominion on God's behalf. Such language, as I have discussed elsewhere, is about the development of the created order, its glorification, and its ordering in service to the Creator. The creation is both good and undeveloped. It belongs to Adam to participate with God in the completion of the creative project. What God does in the six days is the paradigm for human activity, as it is man who is the image of God. Adam is the high priest of creation. Importantly for our discussion, the creation before the flood had a central sanctuary. The garden of Eden was a sanctuary on a mountain. After man's exile from Eden, angels guarded its gate together with the flaming sword (fire and blade are the two instruments of sacrifice) but at the bottom of the mountain the human family conducted its liturgical worship at this site. We understand this from the reference to Sin (a way of referring to the Serpent) "crouching at the door", the context naturally referring to the gate of Eden. Abel is identified as the "guardian of sheep" and Cain a "cultivator of the ground." Adam's dual roles as guardian and cultivator thus pass to two distinct sons. The former language is associated with priesthood, the latter with kingship. Thus, Abel constituted the priestly line. This is why Seth is described as having been appointed in the place of Abel. His birth coincides with people beginning to "call upon the Name of the Lord", a phrase which nearly always occurs in a ritual context, particularly a sacrificial one.

Seth is the appointed heir to Abel's priestly ministry who administers the central sanctuary at the gate of Eden, the place where mankind is called to engage with God in worship. His heir, Noah, conducts liturgical offices as the builder of the ark, described clearly as a three-leveled s temple and as sacred space. After the flood he leads the ascension offering after which God manifests the glory-cloud in the form of a rainbow: compare the language of Ezekiel concerning the rainbow and the cloud. Noah's prophetic word to his sons transmits the priestly ministry through Shem: "Blessed be Yahweh, the God of Shem, and let Canaan be his slave." The name "Yahweh" is the Name liturgically invoked (Ex. 3:15) in the priestly work of the old covenant, as it is the Name "called upon" by Seth and his heirs. The use of this name in the blessing on Shem identifies his line as the line of priesthood. However, the central sanctuary of Eden's Gate was destroyed in the universal flood, challenging mankind's access to God. Shem's descendants are identified in Genesis 10 and 11. The division after the Tower of Babel occurs in the generation of Eber's two sons, Joktan and Peleg. Genesis 10 describes the migration of the Joktanite clans eastward. These were the clans which were "moving east" in Genesis 11:2. The Babel project was led therefore by a partnership of Hamites and Shemites under the bloody rule of Nimrod, identified in sacrificial language as a "mighty slaughterer before the Lord" pointing to the bloody way in which the uniformity of culture around a false liturgy was maintained. The Babel project involved both a city and a tower, both language and lip. Language refers to culture, lip refers to the God whom you worship as David professes: "I will not take the names [of false gods] on my lip." The lip is designed to "call upon the Name of the Lord." City corresponds to language and tower to lip. The tower is meant as a ladder to heaven.

God had not reestablished the sanctuary where He linked Heaven with Earth, and so it was natural that the human family would attempt to reestablish that link on its own terms and so attempt to seize a position in the Heavenly Court. Adam had desired to be "as a god", referring to a member of the heavenly council. The Sethite families had given their daughters to the "Sons of God", another reference to members of that heavenly court (compare the language of Dt. 32:8-9, Job 1-2) as an attempt to marry into the heavenly throne-room and seize the inheritance in that fashion. Here, we see the participation of the Joktanite priestly family in the construction of the false ladder to heaven. Joktan must have been the firstborn because of Peleg's being named after the event of the judgment on Babel. Thus, he was born after his brother's clans had officiated as the priestly family at Babel. Peleg's bloodline is traced in Genesis 11 down to Abram. Abram is led out of Mesopotamia and into the land of Canaan where he builds an altar and "calls on the Name of the Lord" the same phrase being used to describe the ministry of Seth in Genesis 4. We are therefore invited to see a continuity in the roles of Seth and Abram. Additionally, God promises to Abram to make a "great name", the same purpose for which the architects of Babel had acted.

The central sanctuary, according to Deuteronomy 12, is the place where God makes His "Name dwell." The identity of God as Lord, Creator, and Sovereign is rooted and grounded in the concrete link He has with the creation through its ladder to heaven. In Genesis 14, when Abram arrives at the city of Jerusalem, he is given Bread and Wine by the high priest of that city, identified by his throne-name Melchizedek, meaning "king of righteousness." Jewish traditions identify Melchizedek with Shem the son of Noah and heir to the high priesthood transmitted by Adam through the line of Seth. The bringing out of Bread and Wine to Abram is highly significant, for in Genesis 9 Noah's investiture of authority was signified by his consumption of wine in sabbatical rest. Melchizedek pronounces a blessing upon Abram which resembles the blessing pronounced by Noah on Shem. The transmission of priestly office thus passes to the children of Abraham. The essential characteristic of this unique calling is its link with the world's single ladder to heaven. In Genesis 28, Jacob sees a vision of the ladder to heaven in a text which echoes Genesis 11 in reversal. Jacob's ladder to heaven is "truly the gate of heaven" as the name Babel means "gate of God." The reference to its gates provides an additional link with the gates of Eden. After this vision, Jacob prophetically names the city "Bethel" meaning "house of God." And indeed, Bethel is one of the locations at which the Tabernacle dwells.

We see thus that throughout Genesis a major theme is the existence- or lack thereof- of the central sanctuary and ladder to heaven. This sanctuary was of significance for all mankind and was served by a specially consecrated priestly line. Exodus records the actual reestablishment by God of the ladder to heaven, beginning with a description of Israel's being forced to build dwellings and cities for Pharaoh and idolatrous gods- Rameses and Pi-Atum- but concludes with the construction of the Tabernacle, the single house of the true God. In Exodus 19, Israel as a whole is consecrated as the priestly nation. It is Israel's election to be the light of the world, and Israel's mission on behalf of all mankind is to officiate liturgically and politically at the one central sanctuary. The description of the Tabernacle, especially its consecration in Leviticus 8-10, links it in many ways with the garden of Eden. The High Priest is symbolically identified as a microcosm not only of Israel, bearing all twelve tribes upon his shoulders, but the entire human race, being a figure of Adam and being vested with vestments signifying the whole creation. The threefold division of priestly prerogatives opens, in a highly regulated and guarded way, the door of access into the divine presence. The High Priest, bearing all mankind with him, is able to enter once a year into the Most Holy Place where the God of Israel personally dwells. The sacrificial services there also constitute a service on behalf of all nations. On the Feast of Tabernacles, Israel sacrifices seventy bulls in a work of intercession for the seventy nations of the world.

The nature of the central sanctuary is not actually about the elimination of any kind of sacrifice outside of the Temple of Jerusalem or Shiloh Tabernacle. In reality, its purpose is the uniqueness of the singular Name of the God of Israel, lifted as a banner to all nations. Its purpose is as a focal point for all mankind, being the one ladder to heaven where God interacts directly with the human family.

One can see, moreover, that the regulations of Deuteronomy 12 about high places concern the perpetuation of the idolatrous worship of Canaan in the utilization of their cultic sites and sacred trees.

(Deuteronomy 12:2-3) You shall surely destroy all the places where the nations whom you shall dispossess served their gods, on the high mountains and on the hills and under every green tree. You shall tear down their altars and dash in pieces their pillars and burn their Asherim with fire. You shall chop down the carved images of their gods and destroy their name out of that place.

The purpose is to "destroy the name" of the false gods out of their "place" in contrast to the exalted "Name" of Israel's God which will be placed in the central sanctuary. Israel is elected as a "kingdom of priests and a consecrated nation" at Mt. Sinai. The principal goal of the Sinai revelation is the revelation of the pattern of the central sanctuary, which Moses beholds in Exodus 25-31. The language used in Exodus 40 concerning Moses' building of that sanctuary echoes the language used of Noah's building of the ark, and Israel's fundamental constitution is centered on their relationship to the Tabernacle. In 1 Kings 8, Solomon describes the Temple as the focal point of God's fidelity to Israel. When the people and their king honor the divine presence in the Temple, when they turn towards the Temple and pray for God's activity, God answers. This occurs in the reign of King Hezekiah- the first time that a king of Judah actually uses the Temple to beg God's protection. Previous kings used the temple for protection, but only in looting its wealth and using it to placate foreign invaders.

When King David establishes the unique Zion tabernacle (the Temple is built on Mt. Moriah), he organizes a Levitical orchestra with a range of instruments to play in conjunction with the daily liturgy. Gentiles play an unparalleled role in serving the Zion tabernacle, and the ark stands almost without boundaries in relation to the people. The prophets consistently associate Zion with the ingathering of the nations and the redemption of Israel, for it is Zion and its liturgy that manifests and foreshadows Israel's fulfillment of her destiny as the light of the world in a unique way. The genealogies of Chronicles are arranged in order to place the Levitical orchestra in a central position. The history of Adam's bloodline, Ezra is telling us, comes to a certain climax with the birth of a family of musicians for Levitical service. In the Psalter, the Gentiles call upon the people to "sing the songs of Zion", and the outpouring of the Spirit at Pentecost corresponds to the Levitical orchestra, for in the former many languages are spoken in a perfect harmony just as in the latter the plenitude of instruments are harmonized towards a single work of service. The Apostle Paul likewise links the Spirit with music: "be not drunk with wine, but be filled with the Spirit, singing songs, hymns, and spiritual songs."

Thus we must always recall that the central sanctuary has a definite and positive role within the history of salvation. It is not principally a prohibition of sacrificial worship elsewhere, but a commandment to establish a focal point for the gathering of Israel, the divine presence, and proclamation of the Name of God to all nations. Moreover, we see that the prohibition on "high places" is given in the context of eliminating the traditional Canaanite places of worship. These sites had a history reaching back into the evil gods worshiped by the descendants of Canaan, and through intermixture and failure to conquer the land, these traditional cultic sites were syncretized with Israel's religion and wounding the divinely willed unity of the tribes as one nation. The thrice-annual gathering of all Israel to the central sanctuary create social bonds among all the children of Israel and facilitates the development of a national consciousness. The failure to subdue all the land to Israelite dominion and observe the festivals according to God's will allowed for the stunting of this national consciousness, eventually leading to the division of the Kingdoms of Israel and Judah and thus the stunting of the Israelite witness to the Divine Name.

Moreover, the emphasis in Deuteronomy 12 is not so much the specific place chosen by the Lord but the act of election itself. Undoubtedly the theology of the central sanctuary forms an important thread in Moses' overarching intent. Still, it should be recognized that the preeminence and priority of divine election lies near the core of the book, with divine will being the active agent in the election of Israel, the calling of prophets, the arrangement of the Levitical order, and the choice of king. The point is that Israel's constitution is fundamentally divine, and Israel's life and blessing turns on the consistent obedience of faith which the nation owes to God in virtue of His redemptive work in the exodus. For example, Deuteronomy 11 emphasizes the essential nature of rain in the land of Israel in contrast to the Nile in Egypt. Dependence on rain for productive harvests makes concrete the necessity of constant trust in the providence of God: rivers can be expected to remain consistent from year to year, but the coming of rain is unpredictable and demands that Israel trust in the Creator's daily provision.

Moses' sermon to Israel as a whole is arranged according to the Ten Commandments. In each section, Moses explicates God's will in a way which unpacks the logic of each commandment. Deuteronomy 12 corresponds to the Second Commandment which prohibits the worship of God through graven images. According to Deuteronomy, this is because Israel "saw no form" at Sinai. The builders of Babel attempted to build a ladder to heaven from the bottom up- but it was God who built a ladder downwards to Jacob who is then invited to climb it (in Genesis 33, his podvig is completed as he reaches "Sukkoth" or "Clouds") according to God's revelation. In other words, God reveals Himself and we worship Him according to the mode of that revelation. Since Israel beheld no form, their worship of God must be formless. Since God revealed Himself in the commandment to not worship at the traditional high places, Israel could not do so. She must worship God after the pattern set forth by God.

This feature of the text helps elucidate the purpose of other cultic sites besides the central sanctuary in Israel's history. One finds the frequent association of prophecy with the worship at these sites. For example, the altar at Mt. Ebal commanded in Deuteronomy 27 (within Deuteronomy itself!) is given by God through the authorized prophet, Moses. Notably, it follows the instructions given in Exodus 20 concerning the building of altars:

(Deuteronomy 27:4-8) And when you have crossed over the Jordan, you shall set up these stones, concerning which I command you today, on Mount Ebal, and you shall plaster them with plaster. And there you shall build an altar to the Lord your God, an altar of stones. You shall wield no iron tool on them; you shall build an altar to the Lord your God of uncut stones. And you shall offer burnt offerings on it to the Lord your God, and you shall sacrifice peace offerings and shall eat there, and you shall rejoice before the Lord your God. And you shall write on the stones all the words of this law very plainly."

(Exodus 20:24-26) An altar of earth you shall make for me and sacrifice on it your burnt offerings and your peace offerings, your sheep and your oxen. In every place where I cause my name to be remembered I will come to you and bless you. If you make me an altar of stone, you shall not build it of hewn stones, for if you wield your tool on it you profane it. And you shall not go up by steps to my altar, that your nakedness be not exposed on it.'

Such a connection gives the lie to the assumption of biblical critics that Exodus 20:24-26 represents a different and originally independent literary source which was at odds with the central sanctuary evident in the hypothetical "P" and "D." The phrase "cause my Name to be remembered" is also crucial. It suggests the principle of divine initiative in worship- God actively "causes" His Name to be "remembered." This comes from Exodus 3:15 where the Sacred Name is revealed to Moses in his prophetic call:

(Exodus 3:15) God also said to Moses, "Say this to the people of Israel, 'The Lord, the God of your fathers, the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob, has sent me to you.' This is my name forever, and thus I am to be remembered throughout all generations.

The revelation of the Name means the revelation of God's essential character by which we can know Him as faithful and trustworthy. The Name is revealed in the context of announcing the imminent fulfillment of those promises made to the patriarchs. It is set in a ritual context: the glory of God is manifest in the bush, God invites Israel to the holy mountain for sacrifice:

(Exodus 3:18) And they will listen to your voice, and you and the elders of Israel shall go to the king of Egypt and say to him, 'The Lord, the God of the Hebrews, has met with us; and now, please let us go a three days' journey into the wilderness, that we may sacrifice to the Lord our God.'

The word "sacrifice" specifically denotes the "peace offering" within which the sacrificial food is shared between God and Israel. This commandment is given in the same speech where God promises to verify before the "Elders of Israel" His faithfulness by miraculous signs. This sacrificial meal shared between God and Israel occurs in Exodus 24 where the Seventy Elders seal the covenant with Yahweh by eating and drinking as they gaze upon the God of Israel. So we see that the particular Name which is caused to be remembered is the Name which signifies absolute divine faithfulness and theophanic revelation to create a covenantal, marital (thus the joint-meal- a covenant is always a marital bond) link between God and His people. Altars throughout Scripture are miniature holy mountains at the top of which the sacrificial fire and smoke corresponds to the fiery glory of God which dwelt on Sinai, causing it to smoke.

(Exodus 19:18) Now Mount Sinai was wrapped in smoke because the Lord had descended on it in fire. The smoke of it went up like the smoke of a kiln, and the whole mountain trembled greatly.

This language is strongly allusive to the sacrificial altar: the Lord descends in His glory-fire (as He did on the burning bush) and causes smoke to ascend to heaven. This descent by God to creation is matched by a corresponding ascent: the fire comes down, the smoke rises. The revelation of the Divine Name is a matter of divine initiative and is spatially focused. The altar is a miniature mountain, a ladder to heaven which commemorates and perpetuates the union actualized by God. Again, the centrality of divine initiative explains the problem with Israel's high places. In most cases, the high places were cultic sites which had bene built in the service of the devils worshiped by the Canaanites. They were intrinsicaly connected with the "name" of the gods whose "memory" was commemorated at the high place. The revelation of the one God as absolutely supreme and victorious over the devils occurs in the destruction of the high places.

Let's consider one other text in Deuteronomy mitigating against the assumption that it mandates only one altar for sacrificial worship:

(Deuteronomy 16:21-22) "You shall not plant any tree as an Asherah beside an altar of the Lord your God that you shall make. And you shall not set up a pillar, which the Lord your God hates.

The ESV renders "an altar of the Lord your God" with the definite article: "the altar of the Lord your God", creating the impression that it refers to the one altar in the Courtyard of the Tabernacle. Given the design and specific structure of the Tabernacle and Temple, this is unlikely. Moreover the only other place in Deuteronomy where building an altar is mentioned is found in Deuteronomy 27:5-6 at Ebal.

Considering all of the above, let's look at specific instances where a sacrificial altar is legitimately built and utilized by an Israelite after the Torah covenant is made. Given what is said in Exodus 20 and Deuteronomy 12, we should expect that altars are associated with prophecy and are constructed in a place where God has made His Name and presence distinctly manifest. Three examples from Judges come to mind. First, Gideon builds an altar at Ophrah in the preparation for the expulsion of the Midianites. Second, Manoah and his wife build an altar at Zorah in the context of the annunciation of Samson. Third, Israel collectively builds an altar at Bethel in the preparation for making war upon the apostate Benjaminites.

Each of these cases matches the criteria I unpacked above concerning the legitimacy of particular altars. It must be a place where God has manifested in a unique and revelatory way His "Name", making that place a bridge between heaven and earth signified in the altar as a miniature holy mountain from which the smoke lifts up the sacrifice (and the one offering the sacrifice) in an ascent to heaven.

The cases of Gideon and Manoah are remarkably straightforward:

(Judges 6:20-24) And the angel of God said to him, "Take the meat and the unleavened cakes, and put them on this rock, and pour the broth over them." And he did so. Then the angel of the Lord reached out the tip of the staff that was in his hand and touched the meat and the unleavened cakes. And fire sprang up from the rock and consumed the flesh and the unleavened cakes. And the angel of the Lord vanished from his sight. Then Gideon perceived that he was the angel of the Lord. And Gideon said, "Alas, O Lord GOD! For now I have seen the angel of the Lord face to face." But the Lord said to him, "Peace be to you. Do not fear; you shall not die." Then Gideon built an altar there to the Lord and called it, The Lord is Peace. To this day it still stands at Ophrah, which belongs to the Abiezrites.

Here two things are of note. First, given the aforementioned emphasis on the revelation of the Divine Name, we find here that God theophanically manifests to Gideon a specific aspect of His Name. Gideon beholds the glorious presence of God directly but through the sacrificial meal consumed by God, he is bound to him in such a way that he lives. This signifies the peace that is reestablished with Israel through the elimination of the Baalite altars and name in Gideon's work. The altar is constructed precisely in order to manifest the divine Name under its property of peace: "Yahweh is Peace." Second, the altar and its theophany is linked with a rock. Gideon pours broth on the rock and God's fire is manifest thereafter. The symbolism of the rock is frequently associated with the Temple, which in its glorious form is built from stone and where the setting of the foundation stone (Zechariah 4) is of preeminent importance. This is because Yahweh is the "Rock of Ages" throughout the Pentateuch. The word in Hebrew for "glory" also signifies the notion of heaviness and weight. Pharaoh is said to become in his heart "glorious" in his own eyes. Thus, Pharaoh and his armies "sink like a stone." We find also that the Rock is associated with the divine birthgiving of Israel, especially through the gift of the water of life which pours forth to enliven the nation in Exodus. This corresponds neatly to the presence of the spring of the water of life at the top of the holy mountain and the river of life that is said to proceed from the messianic temple in Zechariah 14 and Ezekiel 47. In Genesis 28, a similar scene takes place where God reveals Himself in a ladder built down from Heaven and where Jacob takes the stone on which his head rested and pours oil over it. The pouring of oil signifies the anointing of Jacob's head with the Spirit. He does the same thing at the same place at the completion of his ascesis in Genesis 33. Having been persecuted unjustly between Genesis 28 and Genesis 33, the patriarch Jacob has climbed the ladder to heaven. Beginning at a well, he ends in the clouds, at Succoth.

The journey of heavenly ascent is key in the theology of Judges 6, where, like Jacob in his vision of the Angel of the Lord, sees God "face to face" and yet lives. In that case, the Lord renews His covenantal promise, thus manifesting His fidelity contained in His Name. Jacob himself is renamed "Israel" and renames Luz prophetically as "Bethel" the house of God. The building of the altar occurs as the concrete realization of the action of God to "cause" the "Name to be remembered."

Judges 13 is very similar to Gideon's altar and revelation:

(Judges 13:17-23) And Manoah said to the angel of the Lord, "What is your name, so that, when your words come true, we may honor you?" And the angel of the Lord said to him, "Why do you ask my name, seeing it is wonderful?" So Manoah took the young goat with the grain offering, and offered it on the rock to the Lord, to the one who works wonders, and Manoah and his wife were watching. And when the flame went up toward heaven from the altar, the angel of the Lord went up in the flame of the altar. Now Manoah and his wife were watching, and they fell on their faces to the ground. The angel of the Lord appeared no more to Manoah and to his wife. Then Manoah knew that he was the angel of the Lord. And Manoah said to his wife, "We shall surely die, for we have seen God." But his wife said to him, "If the Lord had meant to kill us, he would not have accepted a burnt offering and a grain offering at our hands, or shown us all these things, or now announced to us such things as these."

Here, the Name of God is again the focus of the text. Like in Genesis 28, God's Name is requested, and here it is manifest according to His working of wonders. In Judges 6, the Name of God is "The Lord is Peace" and in Judges 13 it is "the Lord is Wonderful." Remarkably, the messianic prophecy of Isaiah 9, describing the heir to the throne of David whose kingdom endures forever, incorporates both of these revelations into the "Name" by which He shall be caused: He is "Wonderful" and also the "Prince of Peace." Isaiah 9:1-6 is actually constituted by a series of allusions to Israel's victory in Judges. The Angel of Yahweh is thus identified with the coming messianic seed. Finally, the "rock" is again the locus of the offering taken up by the heavenly flame.

The third example is found in Judges 21, where Israel gathers to Bethel to inquire of God and consider their course of action with respect to the apostate Tribe of Benjamin. According to Judges 20, the people had gathered to Bethel in order to inquire of God, after which they received a revelation. Thus we know it as a place of revelation. However, the text of Judges itself does not clearly fit the criteria specified above concerning the importance of a theophany and the revelation of the Name. However, this is because Bethel had already been the place of exactly such a revelation. Both Judges 6 and 13 allude to Genesis 28 and 33, as noted above. The locale in which these events take place is Bethel- prophetically named by Jacob as the house of God because of the ladder to heaven which is built by God down to earth, identified by the patriarch as the "Gate of Heaven." So this is likewise a place at which God's iniative was preeminent in revealing His character in a manifestation of His presence. The altar constructed at Bethel confirmed Israel in her bond to Yahweh, a bond sealed by the trust formed in Yahweh by His faithfulness to exactly what He signified by His Name.

After the period of the Judges during which there is an established central sanctuary preeminently located at Shiloh (though it does move to different places) we come to the Book of Samuel. Samuel begins with a description of the detestable acts committed by the Israelite priesthood, leading to the desolation of the sanctuary and its exile among the Philistines. Throughout Samuel, the ark of the covenant (the focal point of divine presence) moves from place to place, and after it is recovered from the Philistines it brings curses on Israel so that its administration is managed by Gentiles until it is brought to Zion by King David in 2 Samuel 6. The other part of the tabernacle, however, continued to operate, the two parts only being reunited in the construction of the Holy Temple by King Solomon. A key aspect of the prophetic office is the revelation of the place of worship. The Name is revealed to Moses who also reveals the pattern of the Tabernacle. The prophets are personal focal points of the same Spirit dwelling in the sanctuary. So in Samuel, during the ark's exile, the prophet builds an altar in Ramah where he sits in judgment and to which all Israel is gathered.

We find worship at a "high place" in 1 Samuel 9-10, a place which is called the "hill of God." However, we note that this is near Bethel, a traditional cultic site for the people of Israel rooted in the revelation of the Divine Name to Jacob in the building of the ladder from heaven to earth. Moreover, this is especially associated with the prophetic institution, with Saul's ascent to the hill marking the moment where he receives from other prophets the gift of the Holy Spirit. Finally, David builds an altar in 2 Samuel 24, and this altar is built on the site where the Temple will be constructed.

Turning finally to Mt. Carmel- first of all, given the priority of divine initiative, that the altar of Carmel is authorized by the prophet sets it apart from violations of Deuteronomy 12 at Canaanite cultic sites. But there's more to say than this. Jeroboam in the north created at Bethel graven images dedicated to the worship of Yahweh, fearing the necessity of the people's thrice-annual gathering at Jerusalem. Wishing to maintain social independence from Jerusalem, Jeroboam created graven images and set up an alternative cult and priesthood, actively suppressing any attempts to honor the Jerusalem temple. The work of Elijah and Elisha takes place in the northern kingdom, a kingdom seriously wounded by their lack of unity with the divinely authorized place of gathering and worship for all Israel. These two prophets build up a remmant of Israel in preparation for the coming exile, and they do so by the foundation of uniquely prophetic institutions and ministries which manifest the divine presence to Israel independent of the Temple of Jerusalem. So Elisha is described in terms reminiscent of the temple itself: a walking, talking temple of the Spirit, carrying with him the presence of God resident therein.

The altar at Mt. Carmel has a similar purpose. The supremacy of the one Name of God is manifested in the revelation on this mountain in fire. Moses revealed the Tabernacle to Israel from God: Elijah is described as a Mosaic prophet, actually traveling to Sinai in 1 Kings 19. The ascent of Ahab to "eat and drink" on the mountain at which God had manifested Himself resembles closely the meal of the seventy elders in Exodus 24, precisely in the context of the giving of the Tabernacle plans. Thus we must recognize that the presence of the altar at Mt. Carmel and successive events was never intended to be a manifestation of the normative Sinaitic order. It is precisely a special prophetic mode of the old covenant in response to the apostasy of the priesthood and the idolatrous alternative sanctuary built by apostate kings. The creation of schools of the prophets passes the normative task of teaching the Scriptures from the Levitical priesthood to a tradition of thought transmitted by the prophets themselves to a chain of disciples.

I think this is sufficient to put this biblical-critical objection to rest and manifest its failure to pay attention to the details of the canonical text and its interrelationships. Thanks for the good question!

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

♀ I BEE ALL Holy Sanctified when I Spiritually Live My Own [MO’ = Personal] MOST HIGH [MH = JAH] GENESIS of A HIGHLY Crucified Black Christ [B.C.] that BEE So Biblically Known in Our Scriptural Proverbs of Galactic + Ecclesiastic + Deuteronomic [GED] Codes 2 My Pornographic Psalms of Virgin Mary’s Sexually Promiscuous Sisters that Make Me [ME = U.S. Michael Harrell = TUT = JAH] Adam & Eve Sin ‘cause of My HIGHLY Evolved Black Christ [B.C. = Ezekiel] Raps of Congo Afrikkan [CA] American Atlantis ♀

#U.S. Michael Harrell#U.S. King TUT of Celestial Atlantis [CA]#I Spiritually Live My Own [MO’ = Personal] MOST HIGH [MH = JAH] GENESIS of A HIGHLY Crucified Black Christ [B.C.]#Our Scriptural Proverbs of Galactic + Ecclesiastic + Deuteronomic [GED] Light Code Intel#My Pornographic Psalms of Virgin Mary’s Sexually Promiscuous Sisters#Virgin Mary’s Sexually Promiscuous Sisters that Make Me [ME = U.S. Michael Harrell = TUT = JAH] Adam & Eve Sin#My HIGHLY Evolved Black Christ [B.C. = Ezekiel] Raps of Congo Afrikkan [CA] American Atlantis#MU of Lost Atlantis [L.A.]#U.S. Biblically Black Genesis#U.S. Biblical Black Americans#Ancient Biblically Black Hittite Egyptians of Pre Physical Black American Origins#Satan of Biblically Black Scriptures#Biblically Black American Israelite Indians of Lost Atlantis [L.A.]#Biblically Black Promised Lands#Ancient Black Esoteric Theologies = Holy Scriptures#Black Ebonic Scriptures [BES = Coptic Texts]#Black Scriptural Raps of Biblically Black Allegory Magick#Scriptural Exodus of the Soul

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Judaic Elements of the Philosophy of Language (and Semiotics)

1. Historicity

Historicity seems to be the main thrust of a covenant theology. What is worth keeping this history around if linguistics is primarily synchronic, or a science taking place in the present moment, or somehow within a concept of presence? There are many elements of this history that are synchronic (happening in the present), even though our power to know and understand this topic is not determined by our mutually shared historicity per se, but rather by our already-given ability to do so with our minds. This ability is a (logical) necessity, possessing its own validity to itself.

What Umberto Eco has given to humanity in his book Semiotics and the Philosophy of Language is something like a makeshift Deuteronomic history explicating the chronicles of semiotic investigation. Aristotle is Davidian, then, and Saussure is perhaps Solomonic. This hearkens back, even, to how King David's only sin was to covet his neighbor’s wife. Saussurean linguistics claimed that the signifier was arbitrary, and this was (and is) because the reversal of the signified yielded up or yields up a word that was (and is) of a concrete content and substance.

In Lacanian psychoanalysis, accordingly, this determinacy of a word is the relationship to knowledge which founds the unconscious, the discourse of the Other. Words of language are not themselves yet known to a young child, but his/her/their Mother certainly knows them, because she consistently proves that she knows about them by exhibiting her understanding of need itself. This fact is what the convoluted-looking diagram called "Schema L" gives expression to, pictured below:

Hence my own explanation of the term "need" in Lacanian psychoanalysis: Need isn't for something you require, but for something you've already had before.

For the philosophy of language, there is also the tradition of Hellenism, as well as classical philology, schools of literary investigation concerning dramaturgy and the historianship of Ancient Greek drama. There is found (in the experience of Ancient Greece) the ambiguity of the understanding of the oneiric image; for example, Agamemnon's dream of the eagle and the snake, which was interpreted by an oracle as a mandatory demand to sacrifice his daughter Iphigenia to Poseidon so he could cross the ocean with his men in order to fight in the Trojan War.

One appeals to the dream-image's or symbol's political authority maybe in Homeric epic poetry. But probably hardly anywhere else did it matter in Ancient Greek society, or seem actually true, that the condensations of the dreamwork ought to be metaphorized directly; especially not within the muddy camps of dirty, sweaty, injured Greek soldiers, or among the drunken audience members of a play or a bardic performance on their way home in the dark.

However, its appropriation onstage in an Ancient Greek play amounted to its all-important cultural transmission. Here Friedrich Nietzsche might be an expert in his essay The Birth of Tragedy. But I don't know if contemporary scholars agree with his cultural evaluations, still. Aristotle’s proportional scheme involving Dionysus/cup and Ares/shield gets a more abstract, sublime, and divine-seeming treatment in that essay though, I think. (Dionysus/pleasure and Apollo/intellect, I guess?)

2. Interpretation

The other thrust of a covenant theology might be its relationship to interpretation, but already in the annumeration of a second category or tendency, historicity has been betrayed. But philosophy of language asks, “what is worth keeping this history around?” Thus we see what the schematism is that Umberto Eco would like to implement:

What there is for the ultimate truth of the philosophy of language is that the interpretant of the semiotic triad “sign/object/interpretant” is not a social interpretant, but rather a natural one.

This bears upon the rabbinical praxis of Jesus Christ directly. Is Umberto Eco the Christ-like semiotician bringing me the information I need (or require) to interpret my own analogical “parable” of authentic philosophical perception? (I am referring to my own writing on the relationship between semiosis and symbolization.)

Jesus gave to the general public orally-transmitted parables which stood for the secret, orally-transmitted religious wisdom of the rabbis, drawn from the treasury of knowledge reserved for the Levitical caste, I think (the Pharisees and the Sadducees). The art of Jesus was to translate this wisdom into metaphorical stories for people to share with one another and think about, because they weren't allowed, according to Jewish law, to hear the truth directly. Jesus disagreed with this idea, even though he knew his betrayal of the other rabbis and of Jewish law could be potentially catastrophic to his own religion, and would result in his eventual execution. This is the forgotten part of his story that has lost the characteristic amazement that it really ought to evoke.

Was Jesus something of a performance artist, an actor, a conman to his neighboring Jews, maybe a fellow conspirator with the other rabbis to trick people into caring about their religion again, or the son of God himself perhaps? (People were probably very bored back then, I imagine as well.)

But for me, Jesus protects Love itself, and this has a lot to do with philosophy of language, and with the importance of interpretation. If matrimony is holy, it is because it protects us from our sexual desires hurting us, both physically and psychologically. It promotes a higher organization of sign systems as well, even though this system must be disseminated by a paradigm of “sexual jealousy” in relation to the paternal metaphor.

Why else am I loyal to my lover than for the pleasure of this sign system, even though I am gay no less, which gives me the symbolic mode I need to interpret my own life in a meaningful way that makes my creativity and understanding of nature more elaborate and satisfactory? It's also healthier for me psychologically to stay with someone I love for as long as possible, I think, even though better health is usually just a coincidental side-benefit of a considered behavior.

0 notes

Text

More Mariology from Michelle Mormon

On a Personal Note: I am currently taking a fascinating course in Mariology through my PhD studies. This was a recent paper I wrote that you may find to be of interest. I hope you find this helpful in your own search for Heavenly Mother. – Sincerely, Michelle Mormon (not Molly!)

Introduction

Comparative Mariology seeks to find common ground across religious traditions concerning Marian teachings regarding her role and personhood. However, the speculative nature of Mariology can lead into some uncharted territory that extends beyond traditional viewpoints, including esoteric studies and goddess-based spirituality. If one is not careful, the very foundations of Christianity can be called into question. Nevertheless, since Mariology is speculative, by its very definition, there are no clearly-defined rules outside the framework of traditional Catholic dogma, which leaves Marian studies open to interpretation. The goal of this paper is to examine the differing perspectives that lie beyond the framework of traditional thought, from interreligious, to the cosmic dimensions, to alternative viewpoints, in hopes of finding some common ground that remains true to a ‘biblical’ worldview. However, this is not a task for the faint of heart, because in doing so, deeply held convictions will be called into question in new ways previously unconsidered. Keeping an open mind remains the key to constructing a meaningful Mariology, regardless of one’s theological framework of interpretation.

Comparative Mariology

Comparative religion as an academic discipline can prove both challenging and rewarding. Finding common ground among differing religious traditions with the goal of seeking understanding of the ‘other’ can be rewarding, in that it gives way to a meaningful exchange of information among differing parties. At the same time, it can be challenging to find common ground among varying traditions where very little, if any, similarities exist. Clooney points out, “By such learning, intelligently evaluated and extended, we make deeper sense of ourselves intellectually and spirituality, in light of what we find in the world around us” (Comparative Theology 2010, 5). The goal of interreligious dialogue is not necessarily to convince the other of the ‘correctness’ of either side; rather it is to see what each side has to bring to the table. The end result is not to judge or condemn; rather it is to learn from one another, seek common ground, and most importantly, acknowledge one’s shared history. Comparative religion seeks, first and foremost, to celebrate differences while seeking understanding of the other perspective across cultural and ideological barriers.

In the case of Mariology, it is not all that difficult to find common ground among the various historical religions, as long as one turns to goddess spirituality- the Sacred Feminine, which ties in with the ancient Wisdom traditions, by whichever name it is known – Chokmah, Sophia, or the Shekinah Presence. Sacred Wisdom looks beyond the outward form of the religion to the inward state of the heart. Concerning Mary herself, Luke 2:51 makes it clear that Mary “treasured all these things in her heart” (NRSV), which suggests a quiet, contemplative spirituality characteristic of feminine ancient wisdom. While Wisdom teachings belong to the established tradition, at the same time, they often transcend – and confound – the hierarchy of formalized religion. The Shekinah Presence is a good example of this, as it was “considered feminine in esoteric (not exoteric) Judaism” (Barkhurst n.d., 19- parentheses belong to author.) This is why the Sacred Wisdom traditions are often misunderstood, and must, in many ways, remain hidden or kept underground. Certainly when one begins to examine Marian doctrines, the same principles apply; this makes it easier to examine the role of Mary outside the established perimeters of her familiar Judeo-Christian context.

Swiss author Frithjof Schuon was raised in a Christian household, and while he was, in essence, “an adamant defender of the Divinity of Christ and the other essential truths of this tradition” (Cutsinger 2000, 15), he was not afraid to delve into the deeper mysteries surrounding the Virgin Mary as found outside the boundaries of Christian thinking, including Islam, Buddhism, and Hinduism. His thinking was considered forward-thinking for its time, although it would become part of the Perennialist philosophical school, which seeks to find unity among thinkers of all major world religions, including the philosophy of Plato and the ancients. For Schuon, Mary is regarded as having the status of an Abrahamic Prophetess (in reference to Islam) characterized by her incredible “strength of soul which evokes such Biblical figures as Miriam and Deborah” (“Wisdom of the Virgin” 1968, 1). Simultaneously, Mary is the Eastern (Buddhist/Hindu) concept of Maya personified, as “she personifies the receptive or passive perfections of universal Substance, but she likewise incarnates – by virtue of the formless and occult nature of Divine Prakriti – the ineffable essence of wisdom or spirituality” (Schuon 1968, 3). Schuon is very careful to distinguish between the submissive nature of Mary, as would be consistent with Islamic thought; juxtaposed against his lofty thoughts concerning her cosmic significance “by her supereminence in the whole Abrahamic cosmos” (Schuon 1968, 5). In my observation, to say that Schuon performs a delicate dialectic balancing act would be an understatement, but he does so rather astutely for someone of a Western mindset, even though he does verge outside ‘traditional’ thinking in all respects. One does not have to agree with Schuon, necessarily, to appreciate his ability to make relevant connections.