#deutscher kunstverlag

Text

Among the many prestigious German state art collections the Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen in Düsseldorf certainly is the most junior: formally established in 1961 it nonetheless looks back at an eventful history that started with a bang. In 1960 Minister President Franz Meyers bought the 88 piece Paul Klee collection of American collector G. David Thompson as a sign of compensation for the Nazi years and the outlawry of Klee’s art during these years. This collection in 1961 became the core of the then established state art collection of which Werner Schmalenbach became director a year later. The collection’s legal form progressively was that of a foundation under civil law, a construction that withdrew it from a direct influence through the state government and which assigned a great degree of autonomy to its director. In 2021 Deutscher Kunstverlag published Martje Esser’s dissertation „Werner Schmalenbach und die Stiftung Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen - Eine Staatsgalerie im Aufbau“ which provides a detailed account of both the genesis and development of the art collection and the role Schmalebach played for it. Although the latter had initially proposed to model the collection after the MoMA and add contemporary art to the collection as well Schmalenbach ended up collecting primarily modernist classics of highest profile. As Martje Esser shows Schmalenbach followed a somewhat conservative policy that didn’t include taking risks by adding contemporary artists to the collection that might later prove irrelevant. This general skepticism regarding contemporary art also led to a fallout with the documenta board from which he withdrew in 1967. This notwithstanding Schmalenbach until his retirement in 1990 assembled a significant collection of modern art that includes Mondrian, Pollock, Léger and Picasso.

Martje Esser’s book is a wonderful read that convincingly amalgamates a collection history, the biography of its founding director and the tumultuous politics surrounding it in a complex but at any time highly readable narrative that ultimately also is a art-political portrait of West-Germany.

#werner schmalenbach#art book#art history#collection history#museum history#deutscher kunstverlag#book#modern art

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

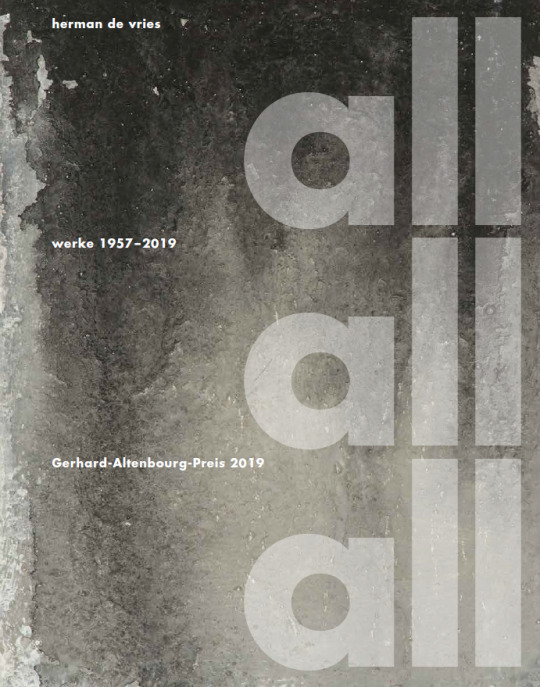

herman de vries – all all all. Werke 1957–2019. Gerhard-Altenbourg-Preis 2019, Compiled by Laura Rosengarten, Edited by Roland Krischke and Lindenau-Museum Altenburg, Texts by Roland Krischke, Anne Moeglin-Delcroix, Laura Rosengarten, Maren Wienigk, Deutscher Kunstverlag, Berlin, 2019 [Exhibition: Lindenau-Museum Altenburg, October 13, 2019 – January 1, 2020]

#graphic design#typography#art#exhibition#catalogue#catalog#cover#herman de vries#laura rosengarten#roland krischke#anne moeglin delcroix#maren wienigk#lindenau museum altenburg#deutscher kunstverlag#2010s#2020s

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Virtual Sketchbook 3

Visual Analysis on “Dream of Joseph” by Anton Raphael Mengs

DESCRIBE PHYSICAL QUALITIES (THE FACTS)

This painting uses oil for its color and is painted on a wooden frame. It is about 42 1/2 × 32 13/16 in. or 108 × 83.3 cm. There is a fair-skinned man, Joseph, and a pale angel that looks human-like. Joseph is on the left sleeping on an armrest with his right fist holding his face. He is also holding a staff-like object in his left arm. He is wearing a yellow blanket around him while also wearing blue clothing underneath. The man also has dark-silvered hair and a beard. The blonde-haired angel looks on the top right looking beneath Joseph wearing white clothing pointing to the left. The wooden frame has gold lines to present the painting in a very delicate design. Joseph takes up more space than the angel does, however the colors and brightness help give a balanced look. The proportion of the angel is placed on the right who is small compared to how bigger Joseph is. The triangular composition is used for Joseph on the right. The contrast is that the angel is brighter than Joseph. The variety in colors helps create an identity in how the art is portrayed.

THIS PART IS ALL ABOUT YOU:

It makes me feel relaxed and astonished especially with the detailed imagery. The level of detail on Joseph and the angel is eye-catching, especially since it took place in the late 1700s. It took five years to finish, and it was well worth putting a lot of time and effort into this painting.

NOW RESEARCH:

Anton Raphael Mengs was a German Bohemian artist who admired himself as a philosopher-painter using the style of Leonardo da Vinci. He also has an interest in mastering the art in the Neoclassical taste. His talent inspired other artists to create a visual language of colors, designs, and expressions that give senses of magnificent grace (Duffy and Mengs). Mengs is also known for making portraits featuring the royal family and the Spanish patricians (Salomon). The figure that he painted for Joseph resembles ancient sculptures and Michelangelo’s work. This painting presents a scene from the Bible where an angel is warning Joseph about King Herold coming to assassinate him and his family and tells him to move out of Bethlehem (Mengs).

THINKING:

This commissioned work of art was originally made as a gift. The subject is Joseph from the New Testament who is told to go somewhere safe from being killed. The artwork shows how majestic and natural the painting is by using his Neoclassical skills to create a masterpiece. Mengs wants to show dedicated artists must be to achieve such extraordinary artwork. The extremely devoted work sends the message of how perfect the piece of art can be.

THE LAST (most important) PART:

I picked this painting because it was eye-catching when I first saw it. Everything from the posture, faces, hair, arms, and legs, and clothes surprised me. It is even more surprised when I found out that this was made in the late 18th century. This work of art that was commissioned as a gift is one of Anton Raphael Mengs’s best paintings. If this was not placed in the Ringling Museum, it would show how far art could go. This must be recognized how incredible the world of art is, especially for its time. Mengs is one of the biggest examples of why art is so phenomenal.

PROOF OF VISIT:

WORK CITED:

Duffy, Michael H. “West’s ‘Agrippina, Wolfe’ and the Expression of Restraint.” Zeitschrift Für Kunstgeschichte, vol. 58, no. 2, Deutscher Kunstverlag GmbH Munchen Berlin, 1995, pp. 207–25, https://doi.org/10.2307/1482702.

Mengs, A. R. (n.d.). Dream of Joseph. eMuseum. Retrieved October 25, 2021, from https://emuseum.ringling.org/emuseum/objects/23046/dream-of-joseph?ctx=8e706bd1-0b32-4022-af88-632edaea071b&idx=1.

Salomon, Xavier F. “GOYA and the ALTAMIRA FAMILY.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, vol. 71, no. 4, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2014, pp. 1–48, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43825565.

0 notes

Text

NEL COMPLESSO monumentale del duomo di Siena, si definisce impropriamente “cripta” una serie di ambienti riscoperti a partire dal 1999, posti al di sotto del livello del coro e pertinenti alla cattedrale romanica che precedette quella attuale, dove si trovano delle pitture murali duecentesche in eccezionale stato di conservazione. Dal 23 marzo si trovano qui esposte, a cura del collaudato tandem formato da Alessandro Bagnoli e Roberto Bartalini, anche otto teste di marmo provenienti dalla facciata del battistero, restaurate da Giuseppe Donnaloia. Il catalogo, pubblicato dall’editore Sillabe di Livorno, contiene un saggio di Roberto Bartalini.

Il titolo Maestri “a rischio” è completato dal sottotitolo Il cantiere del duomo di Siena e le “teste grandi” per la facciata del battistero. Il visitatore potrebbe pensare che si parli di “rischio” riferendosi al degrado che minacciava la conservazione di queste opere. Anche se non è escluso che i curatori abbiano voluto giocare sull’equivoco per incuriosire il pubblico, il vero significato del termine viene subito svelato. L’impiego, da parte dell’Opera del duomo senese, di maestri addetti alla lavorazione della pietra era infatti regolato da differenti rapporti di lavoro: oltre ai “maestri a giornata”, che potevano contare su una certa continuità lavorativa, erano previsti – e spesso numericamente prevalenti – i “maestri a rischio” o “a misura”, la cui retribuzione era stabilita in base al lavoro prodotto. A questo proposito, è difficile non pensare all’attuale diffusione dei contratti di lavoro a tempo determinato.

Furono ingaggiati “a rischio”, tra il luglio e l’ottobre del 1356, cinque maestri, poi pagati per l’esecuzione di ventitré “teste grandi” con “archetti scorniciati con dentelli” : Niccolò di Cecco del Mercia (undici teste), Giovannino di Cecco (sette), Paolo di Matteo (una), Michele di Nello (due), Domenico di Vanni (due).

Restano soltanto le otto che sono state ricoverate nella “cripta” e che erano collocate in precedenza nella parte superiore della sezione centrale del battistero, alle quali non si può oggi attribuire un particolare significato iconografico, mentre se ne percepiscono il valore decorativo e la caratterizzazione fisiognomica, talvolta molto pungente, come nel volto maschile della testa A, segnato da rughe di espressione (fig. 1).

Fig. 1 – Lapicida senese del 1356, Testa virile (A), Siena, Museo dell’Opera.

A Siena il battistero non è, come altrove, una costruzione autonoma a pianta centrale, ma un corpo di fabbrica rettangolare prospiciente la piana di Vallepiatta, a una quota inferiore rispetto alla piazza del duomo, sopra il quale avrebbe dovuto svilupparsi il prolungamento di due campate del coro della cattedrale, previsto a partire dal secondo decennio del Trecento, nel periodo di grande espansione economica e demografica della città sotto il governo dei Nove, che sfociò circa vent’anni dopo nella decisione di costruire una nuova cattedrale che avesse per transetto l’attuale duomo. L’ambizioso progetto non giunse in porto, ma gli studi storici e documentari più accurati[1. si veda in particolare A. Giorgi, S. Moscadelli, Costruire una cattedrale. L’Opera di Santa Maria di Siena tra XII e XIV secolo, München, Deutscher Kunstverlag 2005] hanno chiarito che l’interruzione dei lavori non coincise con la peste del 1348: nella tragica epidemia morì molto probabilmente, con altri artisti come i fratelli Pietro e Ambrogio Lorenzetti e circa metà della popolazione cittadina, il capomaestro del duomo, Giovanni d’Agostino, ma la direzione passò al fratello Domenico, che seguì i lavori del duomo fino al 1358 e ne riprese la direzione nel 1362. L’abbandono dei lavori per il “duomo nuovo” avvenne nel giugno 1357, poco dopo l’insediamento del governo dei Dodici, per motivi essenzialmente strutturali (lesioni e crolli); dopo questo momento l’impegno si concentrò sul lato del battistero.

La peste era individuata come fattore determinante della crisi di metà secolo e spartiacque definitivo nella storia dell’arte del Trecento da studiosi come Millard Meiss[2. Painting in Florence and Siena after the Black Death: The Arts, Religion and Society in the Mid-fourteenth Century, Princeton, Princeton University Press 1951, trad. it. Pittura a Firenze e a Siena dopo la Morte Nera. Arte, religione e società alla metà del Trecento, Torino, Einaudi 1982] e Frederick Antal[3. Florentine Painting and its Social Background. The Bourgeois Republic before Cosimo de’ Medici’s Advent to Power: XIV and early XV Centuries, London, Kegan Paul 1948; trad.it. La pittura fiorentina e il suo ambiente sociale nel Trecento e nel primo Quattrocento, Torino, Einaudi 1960] ma il loro assunto è stato spesso confutato in seguito.[4. Si veda in particolare Luciano Bellosi, Buffalmacco e il Trionfo della Morte, Torino, Einaudi 1974] Anche il proseguimento dei lavori al duomo di Siena e l’attività dei cinque “maestri a rischio” contribuiscono a rendere meno netta la cesura.

Fig. 2 – Lapicida senese del 1356, Testa femminile (G), Siena, Museo dell’Opera.

Le otto teste, ancora collocate sulla facciata del battistero, erano state oggetto dell’attenzione di Bartalini in un suo studio di alcuni anni fa, nel quale ricostruiva la personalità di Domenico d’Agostino, scultore meno noto del padre Agostino di Giovanni e del fratello Giovanni d’Agostino. Il riferimento a “lapicida senese, su modello di Domenico d’Agostino” era allora accompagnato da un punto interrogativo.[5. Domenico d’Agostino, in Scultura gotica senese (1260-1350), a cura di Roberto Bartalini, Torino, Allemandi 2011, pp. 369-382] Nell’attuale catalogo lo studioso è in grado di proporre un’attribuzione per due delle otto teste. Quella indicata dalla lettera G, che raffigura una donna velata (fig. 2), è infatti paragonabile alla Madonna col Bambino di Giovanni di Cecco inserita nell’altare Piccolomini del duomo, databile al 1371.[6. La ricostruzione di Giovanni o Giovannino di Cecco è un risultato di Alessandro Bagnoli, La ‘Madonna Piccolomini’ e Giovanni di Cecco, in Scritti in ricordo di Giovanni Previtali, I (“Prospettiva”, nn. 53-56), 1988-1989, pp. 177-183] Per un’altra testa femminile, quella denominata H, Bartalini fa invece il nome di Niccolò di Cecco del Mercia, la cui opera più nota è il pergamo interno del duomo di Prato, al quale riferisce anche una testa nello sguancio di una finestra del cleristorio orientale della cattedrale senese.

La presentazione dei frammenti scultorei, corredati da dettagliati pannelli illustrativi, ha l’aspetto di una mostra, ma la mancata indicazione di una data di chiusura e la sostituzione in loco degli originali con i relativi calchi autorizzano a immaginare un’operazione museografica di più vasto respiro, con apprezzabili finalità di tutela.

Fig. 3 – Lapicida senese del 1356, Testa maschile (D), Siena, Museo dell’Opera.

Fig. 4 – Lapicida senese del 1356, Testa maschile (E), Siena, Museo dell’Opera.

Scultura a Siena dopo la peste nera: “maestri a rischio”, di G. Ragionieri NEL COMPLESSO monumentale del duomo di Siena, si definisce impropriamente “cripta” una serie di ambienti riscoperti a partire dal 1999, posti al di sotto del livello del coro e pertinenti alla cattedrale romanica che precedette quella attuale, dove si trovano delle pitture murali duecentesche in eccezionale stato di conservazione.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Doge's Palace in Venice: A Tour Through Art and History

In The Doge’s Palace in Venice, Wolfgang Wolters provides an art historian’s guide to the palace, St. Mark’s Cathedral, and Rialto Bridge. After providing a general description of the architecture and history, Welters dives deeper into the history of specific pieces of art in the palace. The art that is featured in Doge’s Palace is very special because it was specially created for the space and most of it was painted on the walls or ceilings so there is no way to see it anywhere else. As doges came into power and the needs of the Venetian government evolved, they would make additions to the palace and commission new, government themed art for the space. One such piece is Doge Francesco Venier presents to Venice its subject cities by Palma Vecchio.

Wolters, Wolfgang. The Doge's Palace in Venice: a Tour through Art and History. Deutscher Kunstverlag, 2010.

0 notes

Text

Haus Lemke

Pütz, Marwin

Hausarbeit im Fach Architekturtheorie an der TU Berlin. Berlin 2019.

Mies van der Rohes vorherrschende architektonische Idee war es, dass die Wände und das Dach eines Gebäudes Teil eines „größeren räumlichen Kontinuums definiert“[1], nicht dieses abschließt. So besteht

Mies van der Rohes Beitrag […] darin, das fundamentale Gesetz und die Logik der Materie zu erkennen und die Wände in einem wohlproportionierten Zusammenspiel zu einem offenen Raumgefüge nach außen und innen zu vereinigen.[2]

Trotz allem entwirft er 1932 das Haus Lemke ohne die Notwendigkeit eines offenen Grundrisses. Anders als häufig beschrieben[3] steht das Haus Lemke scheinbar nicht in der Tradition von Mies‘ Philosophie der Architektur.

Nachdem Mies das Konzept des Freien Grundrisses anhand des Landhauses aus Backstein entwickelte, baute er das Meisterwerk der klassischen Moderne, den Deutschen Pavillon, in Barcelona. Darüber hinaus verbesserte er jenes Konzept, indem er zur Berliner Bauaustellung ein Erdgeschosswohnhaus entwarf, welches unterschiedliche häusliche Programme beinhaltete.[4] Erst danach widmete er sich dem Entwurf des Haus Lemkes. Besonders der Grundriss des Gebäudes unterstützt die Annahme eines Bruchs mit dem zuvor von ihm entwickelten Konzepts.[5]

Aufgrund der finanziellen Möglichkeiten des Auftraggebers, Geschäftsmann Karl Lemke, entwarf Mies das Gebäude eingeschossig und mit einer Grundfläche von 160qm. Das auf einem L-förmigen Grundriss entstandene Haus besteht aus tragenden Ziegelsteinwänden. Den Ansprüchen des Ehepaar Lemkes entsprechend, war das Raumprogramm bescheiden.[6] An das Doppelschlafzimmer im Norden gliedert sich die Toilette und die Garage. Im Süden, zur Straße hin, befindet sich der Eingangsbereich, die Gästetoilette, der Wohnraum, die Küche sowie das Dienstbotenzimmer. Die sogenannte Halle verbindet den Eingangsbereich mit dem Schlafzimmer. Eine Terrasse liegt östlich zwischen Stamm und Arm des L-förmigen Grundrisses. Die Setzung der Wände zeigt deutlich wo jeder Raum verortet ist.

Dahingegen unterteilen beim Landhaus aus Backstein lange, scheinbar ins Leere gehende, Ziegelsteinmauern das Grundstück.[7] Mies schafft es durch sie das Außen und das Innen in Beziehung zu setzen. Eine klare Abtrennung vom Innen- zum Außenraum ist dadurch nur schwer zu fassen.[8] Betrachtet man beim Haus Lemke nur die Stellung der tragenden Wände, insbesondere im Übergang von Halle zum Wohnraum, meint man Mies‘ Idee des freien Grundrisses erkennen zu können. An der, zwischen Halle, Wohnzimmer und Terrasse liegende Mauer befindet sich eine verglaste Fassade. Im Grundriss erweitert sich scheinbar der Innenraum nach außen hin. Würde es sich um eine Öffnung im Sinne des Freien Grundrisses handeln, so läge die Decke auf der Glasfassade auf. Jedoch liegt über der Glasfassade ein gemauerter Fenstersturz. Somit erscheint die Öffnung wie aus der Ziegelwand geschnitten. Während im Landhaus aus Backstein lediglich durch die Stellung der Mauern Durchgänge entstehen, wirkt im Haus Lemke die Öffnung nach außen fast wie eine konventionelle Fensterfassade.

Um die freie Grundrissgestaltung weiterzuentwickeln setzte Mies Stahlstützen ein. So auch in seinem Beitrag zur Weltausstellung 1929 in Barcelona.[9] Die Last der Dachplatte wurde durch Stützen abgetragen. Dies ermöglichte ein freies Stellen von Mauerelementen. Diese bestanden aus edlen Materialien wie Marmor und Quarz.[10] Sie gliederten den Innenbereich und ließen ein fließendes Raumgefüge, ohne feste Begrenzungen entstehen.[11] Im Haus Lemke dagegen wurden nur einfache Materialien wie Ziegelsteine, Holz und Messing verwendet. Darüber hinaus tragen alle Wände die Deckenlasten ab, sodass keine Mauer freistehend ausgeführt werden konnte.

Auch bei dem Erdgeschosswohnhaus, das Mies zur Berliner Bauaustellung 1931 entwickelte, tragen Stützen die Last der Decke ab. Zusätzlich erweiterte er das Konzept des Freien Grundrisses um ein häusliches Raumprogramm. Um den daraus resultierenden Anforderungen gerecht zu werden, umschließt er die Funktionsräume mit massiven Wänden. Alle anderen Mauern streben in den Außenraum.[12] Diese Maßnahmen ermöglichen jede gewünschte Aufteilung der Räume. Zudem kann sich der Wohnbereich dem Garten zu jeder Seite hin öffnen.[13] Obwohl alle bereits genannten kompositorischen Prinzipien wichtig für Mies‘ architektonische Gestaltung sind, wendete er sie beim Haus Lemke nicht an.

In der Gegenüberstellung des Haus Lemkes mit dem des Landhauses aus Backstein, dem Barcelona Pavillon und dem Erdgeschosswohnhaus lässt sich das Fehlen von einigen für Mies van der Rohe wichtigen architektonischen Merkmalen erkennen. Man möchte den Schluss ziehen, das Haus Lemke sei eine Verirrung Mies van der Rohes gewesen. Passt es doch nicht ganz Recht in die Vorstellung einer linearen Entwicklung seiner Architektur. Dennoch entwarf Mies dieses Gebäude, obwohl seine Studien zum Freien Grundriss, zum damaligen Zeitpunkt, bereits fortgeschrittener waren. Die, zu dieser Analyse benutzten, Werke vermitteln jedoch das Bild eines linearen Schaffensprozesses. Es werden jene Gebäude ausgelassen oder nur kurz erwähnt, die nicht einer stringenten Konzeption folgen. Andererseits wird meist von Liebhabern des Haus Lemkes versucht das Haus unbedingt in diese vermeintliche Linearität einzugliedern. Dabei kommt es oft zu Falschinterpretationen, wie dies beim Vergleich des Hauses mit dem Landhaus aus Backstein verdeutlicht wurde. Aber der Schaffensprozess eines Künstlers ist nicht linear. Das Lebenswerk eines Architekten, wie der Entwurfsprozess selbst, ist nicht eine Reihe von rational aufeinander aufbauenden Ideen. Das kreative Schaffen ist verbunden mit Ausbrüchen, Rückschritten und Reminiszenzen. Daher ist anzunehmen, dass Mies‘ Philosophie der Architektur mehr beinhaltet als nur das Konzept des Freien Grundrisses. Welche weiteren Prinzipien Mies‘ Vorstellung von Architektur umfassen sind ein Untersuchungsgegenstand der Möglichkeiten zur Forschung bietet.

_________________________

[1] David Spaeth. Mies van der Rohe. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt Stuttgart 1986. 67.

[2] Werner Blaser. Mies van der Rohe. Verlag für Architektur Artemis Zürich 1972. 18.

[3] „Architekt,“ Freunde und Förderer des Mies van der Rohe Hauses e.V., Zugriff am 25.05.2019, https://www.miesvanderrohehaus.de/architektur/architekt/.

[4] Spaeth. Mies van der Rohe. 71.

[5] Vgl. Abb. 1. Grundriss Haus Lemke.

[6] „Die Bauherren,“ Freunde und Förderer des Mies van der Rohe Hauses e.V., Zugriff am 30.05.2019, https://www.miesvanderrohehaus.de/architektur/die- bauherren/.

[7] ABBILDUNG GRUNDRISS LANDHAUS BACKSTEIN

[8] Blaser. Mies van der Rohe. 18.

[9] ABBILDUNG GRUNDRISS PAVILLON

[10] Blaser. Mies van der Rohe. 26.

[11] Spaeth. Mies van der Rohe. 67.

[12] Ebd. 69-71.

[13] ABBILDUNG ERDGESCHOSSWOHNHAUS

QUELLEN

Blaser, Werner. Mies van der Rohe. Verlag für Architektur Artemis Zürich 1972.

Spaeth, David. Mies van der Rohe. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt Stuttgart 1986.

Freunde und Förderer des Mies van der Rohe Hauses e.V.. „Architekt.” https://www.miesvanderrohehaus.de/architektur/architekt/.

_______________. „Die Bauherren.“ https://www.miesvanderrohehaus.de/architektur/die- bauherren/.

WEITERFÜHRENDE QUELLEN

Andreas Beitin, Wolf Eiermann und Brigitte Franzen, Hrsg. Mies van der Rohe Montage Collage. Koenig Books London 2017.

Noack, Wita. Konzentrat der Moderne: das Landhaus Lemke von Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. Deutscher Kunstverlag München Berlin. 2008.

0 notes

Text

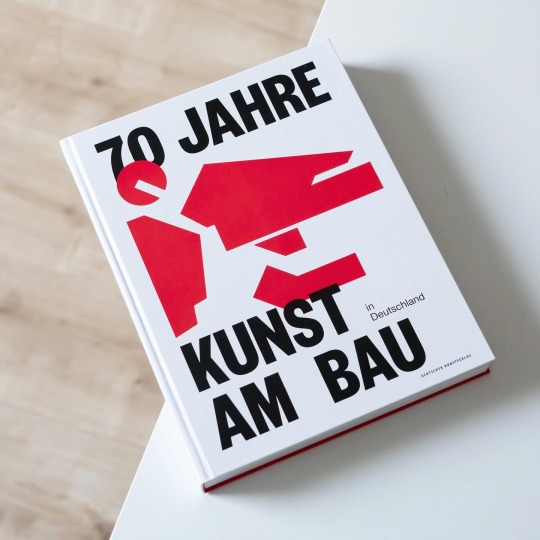

The history of art in architecture or „Kunst am Bau“ in Germany dates back to the Weimar Republic and the Roaring Twenties: as a consequence of the dire economic situation of artists after WWI the interior ministry in 1928 decided to stipulate the inclusion of artists in the artistic configuration of public buildings and to allocate a certain amount of the total building sum to art. After WWII and in view of the again often tense financial situation of artists the German parliament rekindled with this kind of cultural sponsorship and in 1950 adopted legislative measures to include art and artists in public projects. Interestingly and basically at the same time the government of the GDR did the same. Seventy years later the Federal Ministry of the Interior took this double anniversary as point of departure for a retrospective view at a long history of art in architecture in both states: alongside a traveling exhibition the Deutscher Kunstverlag in 2020 published the lavishly illustrated catalogue „70 Jahre Kunst am Bau in Deutschland“ that follows the exhibition’s structure and presents art in architecture in a variety of more or less publicly accessible buildings from federal ministries to military facilities. Artworks in the latter context are a particularly interesting feature since they can only rarely be visited by the public at large. In addition the catalogue also provides information about the development of art in architecture in both German states before and after the fall of the Berlin wall and sheds light on how the changing courses of time influenced art in architecture. The result is a comprehensive retrospective that through its multi-perspective view on the topic in both German states addresses differences and similarities and brings to light a rich heritage that is worth discovering!

30 notes

·

View notes

Photo

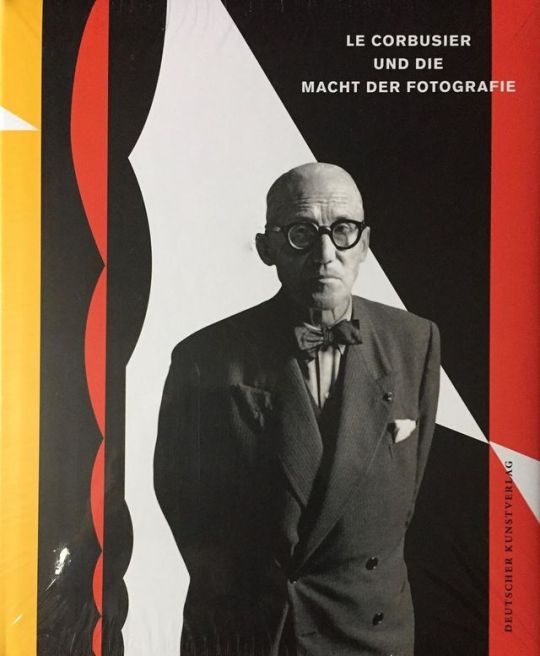

Le Corbusier. Le Corbusier und die Macht der Fotografie. Deutscher Kunstverlag, München und Berlin. 2013. Ausstellungskatalog La Chaux-de-Fonds und Brüssel #lecorbusier #photobook #photobooks #kunstkiosk #kunstkioskimhelmhaus http://bit.ly/2MLARJu https://www.instagram.com/p/B06Pl_LoAZg/?igshid=7i6i2jx3wcku

0 notes

Link

As the essays in the present volume demonstrate with richness of detail, the creation of the Other of the Christian West by means of literary and visual representations long predates the nineteenth-century era of Western imperialism. Trade and religious proselytising in the medieval and early modern ages were as important as later colonial expansion in making possible the intercivilisational encounters that inspired the representation of the Other. Equally significant is the fact that such representation was by no means a Western prerogative. By examining early modern Thai imagery of foreign people, this chapter seeks to broaden the analytical scope of the representation of alterity as a practice common to societies across cultural divides as well as across history.

Peleggi, Maurizio. "The Turbaned and the Hatted: Figures of Alterity in Early Modern Thai Visual Culture." In Anja Eisenbeiss & Lieselotte E. Saurma-Jeltsch (eds.), Images of Otherness in Medieval and Early Modern Times: Exclusion, Inclusion and Assimilation. Deutscher Kunstverlag (2012).

Siam’s intense relations with China, Japan, the Safavid Empire and Europe reflected its central role in trans-Asian maritime trading networks during a period of some two hundred years that historian Anthony Reid has termed the “Age of Commerce,” from c. 1450 to 1680.5 Siam’s territory proper covered only the central region of present-day Thailand—a flat agricultural land in the lower basin of the Chaophraya River—but its suzerainty extended over vassal principalities to the Malay Peninsula in the south and the Khorat Plateau in the east. The royal capital, Ayutthaya, was situated on an isle at the confluence of the Chaophraya and the Pasak rivers, and was crisscrossed by a network of canals that demarcated distinct residential and market areas and provided easy internal transportation (the Gulf of Siam was two days away by boat).

Mirroring the kingdom’s dual nature as an agrarian state and a maritime entrepôt, Ayutthaya fulfilled a dual function: seat of royal power and port city. The main island was an area of five square kilometres occupied by the royal palace, the residences of the aristocracy and major temples and monasteries. Outside of it lay the settlements of Siamese commoners and of traders from China, Japan, Vietnam, Cambodia, the Malay archipelago, coastal India and Persia. The Portuguese established a trading station there in 1516, five years after founding a colonial settlement in Malacca. In 1608 came the Dutch and in 1612 the English. The first Frenchmen to arrive in 1662 were missionaries dispatched with the blessings of Pope Alexander VII, who proclaimed Siam a vicariate apostolic for the spread of Catholicism in the East; merchants and diplomats followed suit. Foreigners were identified by ethnonyms that are still in use today: chin (a phonetic term) for the Chinese; khaek (meaning “visitor” or “guests”) for Arabs, Persians and South Indians, homogenised in the eyes of the Siamese by the common Islamic faith; and farang, an adaptation of the medieval Arabic frangi (Frank), for Europeans regardless of nationality. It has been calculated that in the mid-seventeenth century Ayutthaya had some 150,000 residents (at a time when Paris had a population of about half a million).

[...]

Here, the figures of khaek and farang clearly represent the Other of Buddhism, and hence of the Siamese people. Their representation serves the didactic goal of the murals: affirming Buddhism’s superiority over foreign faiths. And if the Christian farang are made to marvel at the power of the Buddha, the Muslim khaek are actually made to suffer its consequences. The substitution of the latter for the heretics of the Buddhist scriptures appears to be the ingenious solution the anonymous artist found to the predicament of how to give visual representation to such an obscure subject as a theological dispute for a provincial audience of devotees. It is worth noting that, in spite of religious toleration in Ayutthaya which made it possible for Muslims to practise their faith and for Catholic missionaries to attempt evangelisation, Buddhism’s primacy was never under any threat and so its superiority hardly needed to be asserted. Given the execution of the murals in 1734, by which time the foreign presence in Siam had dwindled considerably, the two mural scenes could be read as alluding to the historical event of this retreat. But representing Muslims and Christians as the vanquished Other in the context of the Buddha’s life could also be interpreted as a way of naturalising, and hence neutralising, them as elements of the Siamese universe.

0 notes

Text

William Petty, "The Burgis Views of Berlin =: Particularly That of Nehemiah" (Deutscher Kunstverlag, 1963)

0 notes

Text

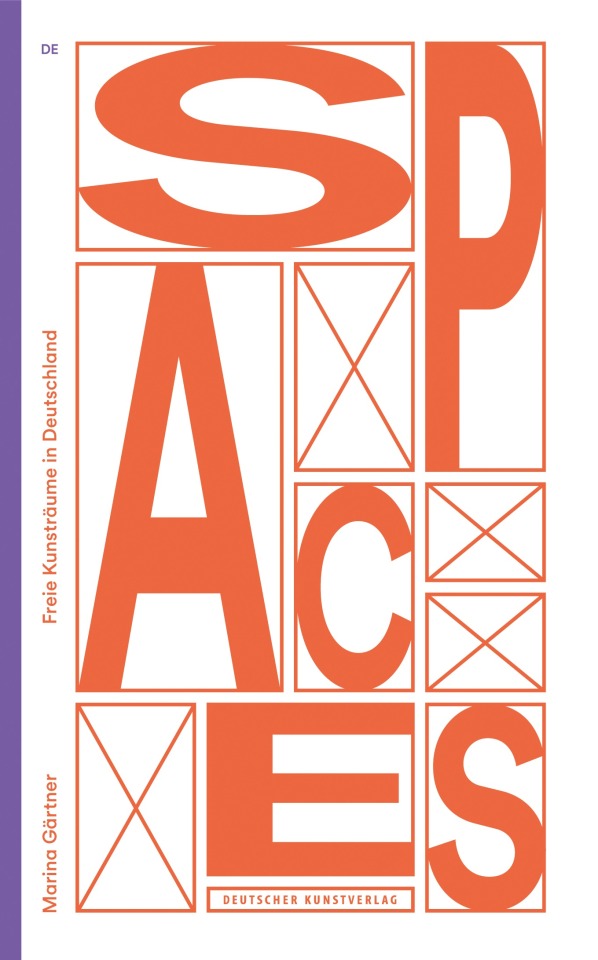

Rezension: Marina Gärtner, SPACES. Freie Kunsträume in Deutschland

Nach wie vor ist der Begriff Alternativkultur mit einem negativen Beigeschmack behaftet. Ein Grund dürfte darin liegen, dass sich die freie Kulturszene in der Vergangenheit meist an ein jüngeres Publikum richtete und oft aus dem Umfeld der Punks oder Hausbesetzer-Szene stammte. Dass sich in den vergangenen Jahren hier ein massiver Wandel vollzogen hat, beweist die Fotografin Marina Gärtner mit…

View On WordPress

#Deutscher Kunstverlag#freie Kunst#Harry Pfliegl#Kunst#Kunsträume#Leipzig#Marina Gärtner#Raum.Weisz#Reisen#SPACES#Städtereisen

0 notes

Text

Verre Églomisé

...EINE ANDERE ART VON MALEREY: HINTERGLASGEMALDE UND IHRE VORLAGEN, 1550-1850 (...a Different Kind of Painting: Verre Églomisé Paintings and Their Models, 1550-1850). Wolfgang Steiner et al. Schaezlerpalais, Kunstsammlungen und Museen Augsburg, 2012. Published by Deutscher Kunstverlag, Munich. 384 pp. 31 x 25 cm. ISBN 9783422071179 In German.

Indexing: Western, Europe — Several Periods, 1600-1800 — Painting

Plans: 69,50

Worldwide Number: 034982

Hardcover $125.00

#Schaezlerpalais#Kunstsammlungen und Museen Augsburg#Deutscher Kunstverlag#art#painting#exhibition catalogue

0 notes

Photo

Hans Scharoun (1893-1972) was an accomplished draughtsman powered by an overwhelming imagination. Already at the age of 16 the young Scharoun drew extensively in his free time and in art class, drawings in which he reflected the architecture of his time and his hometown Bremerhaven in autonomous architectural fantasies. Often neatly signed, dated and titled they lay the foundation of a singular body of work comprising more than a thousand individual drawings that are not related to a concrete project. Scharoun, who was the first postwar president of the Akademie der Künste (AdK) in West-Berlin, made over his estate to the AdK already before his death. As long-term head of the institution’s archive Eva-Maria Barkhofen researched Scharoun’s drawings and gained intimate knowledge of their development over time. As conclusion of her decades-long research Deutscher Kunstverlag recently published Barkhofen’s „Hans Scharoun - Architektur auf Papier: Visionen aus vier Jahrzehnten (1909-1945)“, a comprehensive analysis and overview of Hans Scharoun’s drawings focusing on the years 1909 to 1945. But in contrast to earlier publications on Scharoun’s drawings the author this time not only focuses on the famous expressionist drawings of the post-WWI years and the „Gläserne Kette“ connection but devotes ample space to his pupil and student drawings as well. During these formative periods Scharoun experimented with contemporary influences ranging from Art Déco over to the Heimatschutzstil to architects like Frank Lloyd Wright, Hans Poelzig and Eliel Saarinen. Interestingly he already in 1909/10 developed first organically shaped architectures in a series of six drawings of church remodelings, early hints at what was to come once he became an architect. Barkhofen in turn contextualizes these drawings, points at reference buildings and provides additional biographical context and archival material.

In addition to the research surrounding Scharoun’s drawings it is worth pointing out that the they are consistently reproduced on full pages, a feature that allows for detailed examinations. With that said the book rightly deserves being named a reference work.

#hans scharoun#monograph#organic architecture#architecture#germany#architecture book#architectural drawings#book#art history#architectural history

25 notes

·

View notes

Photo

It was a homecoming when in 1968 the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin was solemnly opened: over three decades after he had left Germany for Mies van der Rohe (in absentia) things came full circle with his only postwar building in his home country. Recently it has been reopened after an extensive and standard setting renovation through David Chipperfield, a perfect occasion to look back at the building‘s history: the Deutscher Kunstverlag with the recently published volume „Neue Nationalgalerie - Das Museum von Mies van der Rohe“ offers a detailed walkthrough of the building from its inception up to the collection it houses. But although the architecture has long been revered as a masterpiece its qualities as a museum have continuously been criticized, especially the fully glazed central pavilion. With regards to the latter a quartet of essays by Fritz Neumeyer, Dirk Lohan, Wolf Tegethoff and especially Beatriz Colomina shed light on the misunderstanding and particularities of Mies’ design and concept of a museum: since 1943 he continually worked on museum proposals and refined his particular vision of a universal space, the artwork as constituent of it and the relation between spectator, artwork and the outside. Inspired by Karl Friedrich Schinkel‘s Altes Museum also in Berlin Mies developed a building that enabled visitors to ambulate between artworks framed by the city, the changing seasons and the changing light. This full promenade architecturale is achieved through the majestic prodium, its terrace, the below lying exhibition spaces and, last but not least, the sculpture garden. Against this background the Neue Nationalgalerie surely is a museum challenging curators and visitors alike but one that ultimately rewards mutual dialogue.

Among the many books written about the Neue Nationalgalerie the present monograph stands out as a perfect amalgam of impressive visual documentation and profound study: extensive photographic material is accompanied by in-depth texts that range up to Erik Spiekermann’s analysis of the type font used by Mies and as such provide a most comprehensive account of an absolute architectural icon.

#mies van der rohe#monograph#architecture#germany#architecture book#art history#book#german architecture#nachkriegsmoderne#nachkriegsarchitektur

62 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Although I don’t conform wit the the author’s overly critical reception of traditional forms of mosque architecture I nonetheless am of the opinion that this an equally interesting and important little book: Christian Welzbacher’s „Europas Moscheen - Islamische Architektur im Aufbruch“, published by Deutscher Kunstverlag in 2017. Today mosques are a visible yet often controversial part of many a townscape in Germany and Europe, having developed from backyard-ish provisional buildings into fully developed, self-assured pieces of religious architecture. Welzbacher offers a brief cross section of mosque architecture in Europe but primarily focuses on modern mosque architecture of the late 20th and early 21st century. The very plurality of formal solutions is astonishing and so is the number of modern mosques in Europe departing from the stereotypical images we (I) have of what a mosque looks like. For me the book opened a whole new field of interest and one that I will surely look into deeper in the future as it not only touches architecture and art history but also topics like integration, historic preservation and migration history.

21 notes

·

View notes