#do you guys care about postpunk

Text

i should post my music books collection i’ve got some good ones actually

0 notes

Photo

A very special fireside interview with XUXA SANTAMARIA

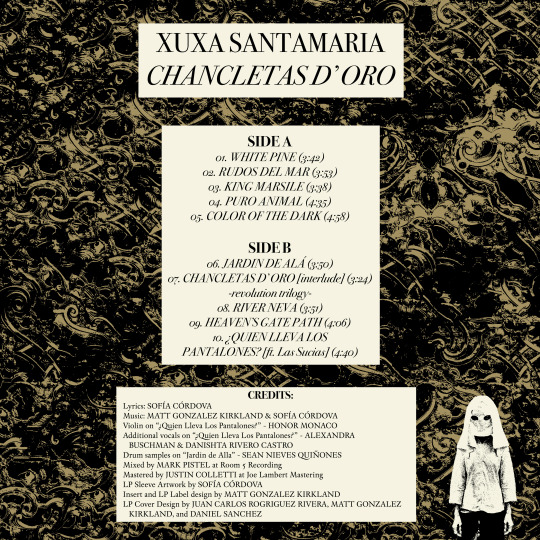

Check Insta for our thoughts on this landmark album from Oakland duo XUXA SANTAMARIA. Stay right where you are to read a really fun interview I scored with the band this week. They’ve just released Chancletas D’Oro on Ratskin Records out of Oakland and Michael blessed me with my very own copy. It was so good I knew I needed to tell you all about it and I wanted to pick their brains a little bit, too. Without further ado, please enjoy:

//INTERVIEW

You’re still breaking into indie world at large, but you’ve already got a huge following back in California and your home-base in Oakland. What has it been like to be featured in major outlets like The Fader?

SC: We are a funny project; we ebb and flow from being total hermits to having periods of relatively high visibility (relative to aforementioned hermit state). I wouldn’t say we have a huuuge following in CA but I do think that the ‘fandom’ we’ve developed here is really genuine because we don’t play shows out of an obligation to remain visible but instead do so because we feel super passionate about the work and the audience and I think people respond to that energy. I for one, and perhaps this is because of my background in performance, have a hard time performing the same stuff over and over without change which accounts for us being selective with our playing live. That’s also why videos are such an important part of what we’re about. The piece in The Fader was important to the launch of this album because it established some of the themes and, to an extent, the aesthetics of this album in a way that can be experienced outside of a live setting. None of this is to say we don’t like playing live, in fact we love it, we just like to make our sets pleasurable to ourselves and to our audience by constantly reworking it. We strike a weird balance for sure but we’ve made peace with it. If we ever ‘make it’ (lol) it’ll be on these terms.

Chancletas D'Oro is a pretty incredible record and while it reminds me of a few bands here or there, it’s got a really fresh and unique style that merges dance with all sorts of flavors. How would you describe your music to someone who is curious to listen?

MGK: Haha, we generally struggle to describe our music in a short, neat way (not because we make some kind of impossible-to-categorize music, but just because it’s the synthesis of a ton of different influences and it’s hard for US to perceive clearly). But with that caveat in mind - IDK, bilingual art-punk influenced dance/electronic music?

SC: Thank you for saying so, we’re pretty into it :) Like Matt says, we struggle to pin it down which I think is in part to what he says – our particular taste being all over the place, from Drexciya to The Kinks to Hector Lavoe- but I think this slipperiness has a relationship to our concept making and world building. As creative people we make and intake culture like sharks, always moving, never staying in one place too long. Maybe it’s because we’re both so severely ADHD (a boon in this instance tbh) that we don’t sit still in terms of what we consume and I think naturally that results in an output that is similarly traveling. Point is, the instance a set of words - ‘electronic’, ‘dance’, ‘punk’- feel right for the music is the same instance they are not sufficient. I propose something like: the sound of a rainforest on the edge of a city, breathy but bombastic, music made by machines to dance to, pleasurably, while also feeling some of the sensual pathos of late capitalism as seen from the bottom of the hill.

The internet tells me you’ve been making music as Xuxa Santamaria for a decade now. What has the evolution and development of your songwriting been like over those ten years?

MGK: Well, when we first started out as a band we were so new to making electronic music (Sofia’s background was in the art world and mine was in more guitar-based ‘indie rock’ I guess - lots of smoking weed and making 4 track tapes haha), so we legit forgot to put bass parts on like half the songs on our first album LOL. We’ve learned a lot since then! But in seriousness, we’ve definitely gotten better at bouncing ideas back and forth, at putting in a ton of different parts and then pulling stuff back, and the process is really dynamic and entertaining for both of us.

SC: This project started out somewhat unusually: I was in graduate school and beginning what would become a performance practice. I had hit a creative roadblock working with photography - the medium I was in school to develop- and after reading Frank Kogan’s Real Punks Don’t Wear Black felt this urge to make music as a document of experience following Kogan’s excellent essay on how punk and disco served as spatial receptacles for a wealth of experiences not present in the mainstream of the time. I extrapolated from this notion the idea that popular dance genres like Salsa, early Hip Hop, and Latin Freestyle among many others, had served a similar purpose for protagonists of a myriad Caribbean diasporas. These genres in turn served as sonic spaces to record, even if indirectly, the lived experiences of the coming and going from one’s native island to the mainland US wherein new colonial identities are placed upon you. From this I decided to create an alter ego (ChuCha Santamaria, where our band name originally stems from) to narrate a fantastical version of the history of Puerto Rico post 1492 via dance music. We had absolutely no idea what we were doing but I look back on that album (ChuCha Santamaria y Usted - on vinyl from Young Cubs Records) fondly. It’s rough and strange and we’ve come so far from that sound but it’s a key part of our trajectory. Though my songwriting has evolved to move beyond the subjective scope of this first album - I want to be more inclusive of other marginalized spaces- , it was key that we cut our teeth making it. We are proud to be in the grand tradition of making an album with limited resources and no experience :P

We’re a big community of vinyl enthusiasts and record collectors so first and foremost, thanks for making this available on vinyl. What does the vinyl medium mean to you as individuals and/or as a band?

MGK: I think for us, it’s the combination of the following: A. The experience of listening in a more considered way, a side at a time. B. Tons of real estate for graphics and design and details. C. The sound, duh!

SC: In addition to Matt’s list, I would just say that I approach making an album that will exist in record form as though we were honing a talisman. Its objecthood is very important. It contains a lot of possibility and energy meant to zap you the moment you see it/ hold it. I imagine the encounter with it as having a sequence: first, the graphics - given ample space unlike any other musical medium/substrate- begin to tell a story, vaguely at first. Then, the experience of the music being segmented into Side A and Side B dictate a use of time that is impervious to - at the risk of sounding like an oldie - our contemporary habit of hitting ‘shuffle’ or ‘skip’. Sequencing is thus super important to us (this album has very distinct dynamics at play between sides a/b ). We rarely work outside of a concept so while I take no issue with the current mode of music dissemination, that of prioritizing singles, it doesn’t really work for how we write music.

MGK: We definitely both remain in love with the ‘album as art object/cohesive work’ ideal, so I would say definitely - we care a lot about track sequencing, always think in terms of “Side A/Side B” (each one should be a distinct experience), and details like album art/inserts/LP labels etc matter a lot to us.

What records or albums were most important to you growing up? Which ones do you feel influenced your music the most?

SC: I know they’re canceled cus of that one guy but I listened to Ace of Base’s The Sign a lot as a kid and I think that sorta stuff has a way of sticking with you. I always point to the slippery role language plays in them being a Swedish band singing in English being consumed by a not-yet-English speaking Sofía in Puerto Rico in the mid 90s. Other influences from childhood include Garbage, Spice Girls, Brandy + Monica’s The Boy is Mine, Aaliyah, Gloria Trevi, Olga Tañon etc etc. In terms of who influences me now, that’s a moving target but I’d say for this album I thought a lot about the sound and style of Kate Bush, Technotronic, Black Box, Steely Dan, ‘Ray of Light’-era Madonna plus a million things I’m forgetting.

MGK: Idk, probably a mix of 70-80s art rock/punk/postpunk (Stooges, Roxy Music, John Cale, Eno, Kate Bush, Talking Heads, Wire, Buzzcocks, etc etc), disco/post-disco R&B and dance music (Prince, George Clinton, Chic, Kid Creole), 90s pop + R&B + hip hop (Missy & Timbaland, Outkast/Dungeon Family production-wise are obviously awe-inspiring, So So Def comps, Jock Jams comps, Garbage & Hole & Massive Attack & so on), and unloved pop trash of all eras and styles.

Do you have any “white whale” records that you’ve yet to find?

MGK: Ha - the truth is that we’re both much more of a “what weird shit that we’ve never heard of can we find in the bargain bin” type of record buyer than “I have a custom list of $50 plus records on my discogs account that I lust over”.

SC: Not really, I’m wary of collectorship. That sort of ownership might have an appeal in the hunt, once you have it do you really use it, enjoy it? Funnily, I have a massive collection of salsa records that has entries a lot of music nerds would cry over (though they’re far from good condition, the spines were destroyed by my Abuela’s cat, Misita lol, but some are first pressings in small runs). For me its value however, comes from its link to family, as documents from another time and as an amazing capsule of some of the best music out of the Caribbean. I’m glad I am their guardian (a lot of this stuff is hard to find elsewhere, even digitally) but I live with those records, they’re not hidden away in archival sleeves, in fact, I use some of that music in my other work. Other than that, the records I covet are either those of friends or copies of albums that hold significance but which are likely readily available, Kate Bush’s The Dreaming or Love’s Forever Changes, or The Byrds Sweetheart of The Rodeo as random examples

Finally, is there a piece of interesting band trivia you’ve never shared in another interview?

SC: haha, not really? Maybe that we just had a baby together?

//

Congrats on your new baby, and also for this wonderful new album. It was a pleasure chatting with you and I can’t wait to see what the future has in store for you and your music!

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

A wonderful and frightening world.

I’ll begin with a confession: I saw two of the best shows of my life back in 2006, and I don’t remember either of them as well as I’d like to. What I really remember is the feeling that I was at something unique, something that would never happen again. As it turned out, I was right.

The first of the shows was The Fall, one of the two greatest bands to come out of the post-punk movement, a genre as brilliant and short-lived as a firefly. Post-punk came out of the bright flare of British punk in 1977. The name meant what it said: It came, chronologically, after punk, and that seemed to mean it could be anything—any kind of music, any sound you wanted to make. It meant bands with names like Kleenex and Au Pairs and Cabaret Voltaire. Post-punk was there until, one day or one year, it wasn’t.

But The Fall—a band that spun entirely around the existence of Mark E. Smith, its lead singer and primary songwriter—never went away. I must have seen a hundred references to them in the imported music magazines I pored over as a teenager before I ever heard them. The references were never like the references to other bands, which ran the gamut from jokey to contemptuous to adoring. The Fall were like some natural landmark that had been standing for eons, and people talked about them as if they were at once utterly awe-inspiring and utterly ordinary. When Mark E. Smith died last month, it felt as strange and wrong as if someone had just said that Niagara Falls had run out of water.

And now here they were in Tucson, after scheduling and cancelling two shows since 2002. I thought I would never get to see them. My friends and I heard them blaring from the sidebar at Hotel Congress and rushed to push our way into the crowd to see them. Smith was cigarette-thin, his face wound in a perpetual unreadable scowl. He bobbed around the stage like a dreidel, not seeming to notice the crowd.

The other people in the band were unknown to us; the lineup of The Fall never held still, with members coming and going at Smith’s whim. A week after the show we heard he’d quarreled with the opening act and fired them from the tour; shortly after that, he’d fired the entire lineup of his band. By all accounts Mark E. Smith was one of the crabbiest and most unpredictable souls on the face of the planet. I didn’t regret not meeting him.

And yet I’ve also heard that Mark E. Smith—MES, everyone called him—was a nice guy, sometimes, capable of extraordinary kindness to random people. He opens the last interview he ever gave by telling the interviewer, whom he knew, how happy he was to be talking to him again, and it feels real. Everything his band ever did feels real, even if all but one of the players changed from album to album. Even the titles of those albums—I Am Kurious, Oranj; Hex Induction Hour; Live at the Witch Trials, The Wonderful and Frightening World of The Fall—are brittle, tetchy, highly suggestive. The repeated chants of “Hey, hey, hey” in “Copped It” haunt me like a voice that followed me out of a dream.

Their sound was tightly focused around a few elements—a clip-clop beat that reminded you sometimes of a carousel horse going round and round, humming keyboard notes as bright and vivid as kindergarten construction paper colors, and MES himself reciting his strange magical-realist poetry in a voice as flat as concrete. And that was The Fall, for decades and decades, and it is unreal to imagine them gone.

I got to see postpunk’s other greatest band, The Slits, a few months later—at the same venue, oddly enough. The Slits were a band so strange they didn’t seem to be of this Earth. They were, at least at first, a trio of teenage girls who came from the original punk scene—they toured with The Clash before they had quite learned to play their instruments—and their music sounded like no other phenomenon. Their style, which in their first performances came close to being completely atonal noise, had by the time of their first album evolved into something that moved like slowed-down reggae but also stopped and started at random, with squeaks and trills and ghostly moans and other noises you couldn’t quite categorize hissing out of the speakers like those cans of compressed air. And that was what they sounded like when I saw them.

In one of the strangest moments of my life as a writer, I got to briefly interview lead singer Ari Up. I don’t have the tape of the interview anymore—I recorded it on my friend’s phone and couldn’t figure out how to save it—but it was less an “interview” than a rambling conversation that went all over the place, and from which I ended up having to extract a few uncharacteristically normal-sounding quotes for the story I wrote for my university newspaper the next day, which I’m still proud of. It was, actually, a conversation that felt very much like a Slits song.

Ari Up died of cancer in 2010, and I still remember the sense of shock and grief I felt, probably harder than I would have felt otherwise because I had met her. But it wasn’t shock I could share with the world, not like the deaths of Joe Strummer or David Bowie. A few months after that, Poly Styrene of X-Ray Spex—whose 1977 album Germfree Adolescents is as magical and luminous as snow on Christmas Eve—died, and I felt grieved that, for all the world seemed to care, she hadn’t even existed. Even now, when people talk about punk, nobody ever mentions X-Ray Spex. And, for that matter, they rarely mention The Slits. Did they even matter?

They did. Nothing I have heard since underlines the sheer strangeness of existence, the unlikeliness of being alive, so well as these now-ancient records by people who weren’t so much aspiring rock stars as they were aspiring cranks and weirdos—not pursuing success so much as pursuing an impenetrably private vision, and turning themselves into the artists they needed to be in order to express it. It’s no surprise that many of them, once they were done communicating that vision, just disappeared back into private life. What was unique about The Fall was that they never got to the end of their own vision, never exhausted what it had to give them—and us. Had their singer not been mortal, you felt they could have kept on going for centuries.

I thought of all this when Mark E. Smith died last month, of all the music that engulfed my life when I was younger, the bands that meant so much to me. I feel a strange sense of grief that I’ve spent so much of my subsequent life not listening to these bands, not even thinking about them. I never feel guilty for not listening to The Beatles, my favorite band at the age of 14, though I’m always delighted to come back to them—The Beatles, I somehow feel, are doing just fine without me. But these bands feel precious and personal to my world, like a houseplant that will wither if I don’t pay enough attention to it. This sound felt like my sound, waiting to be discovered, when I was in my late teens, and no matter how many other bands I come to like and enjoy throughout my life, no other sound will ever be that sound.

Perhaps you have a band like this—perhaps even just a song. As likely as not, your band is not my band. Even if it is, the songs that move you are probably not the ones that move me—and even if they are, we are probably moved by different things. But it doesn’t matter, because what we feel is really the same. And if I feel braver now after finding my way back to these records, readier to talk back to a world that never stops trying to shut all of us up, I can only hope that the records that mattered like this to you, that promised you your own universe, can do the same for you.

0 notes