#especially through the lens of current politics and social organizations

Text

By: Frederick R. Prete

Published: Apr 18, 2023

In a recent article for FAIR Substack, David Ferrero argued convincingly that school programs designed to view their subject matter through an “ethnic studies”— rather than an “ethnic histories”— lens can be “reductive, tendentious, divisive, and doctrinaire.” He also pointed out that this narrow approach, which includes indiscriminate references to putative ‘racial’ groups (“black”, “Asian”, “white”, etc.), is antithetical to the ideal of bridging our “ethnic and religious differences in the service of forging a shared civic identity.”

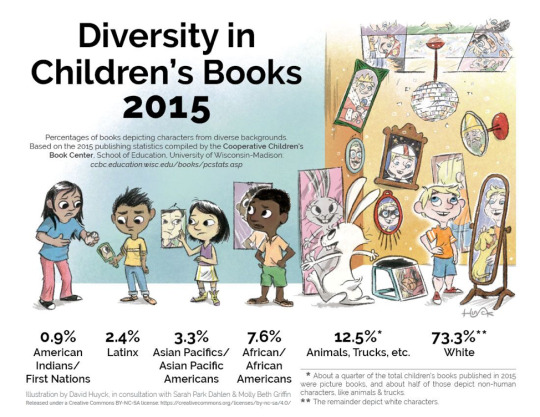

While I am in complete agreement with Ferrero, I would go even further. I believe that there is a fundamental conceptual flaw in using current racial categories in any academic analysis. These categories have become so hopelessly ambiguous that they are virtually meaningless, and they now function as terms of convenience, used only when they serve a political agenda. This is true throughout academia, but is most evident in discussions about academic achievement.

In biology, “race” is a taxonomic term, and like all biological terms, it can be ambiguous. Sometimes it’s used as a synonym for subspecies. Most often, however, it refers to a group of organisms that is biologically or geographically distinguishable from other groups within a species but is still able to reproduce with them.

On the other hand, when referring to humans, most contemporary scientists consider ‘race’ a social construct based on societal definitions without any inherent physical or biological meaning. That point of view is based on the understanding that there is more genetic variability within human racial groups than between them. In other words — to paraphrase the evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins — whereas human sex is binary (there are only two), race is a spectrum.

Ironically, despite the fact that most academics consider human racial categories to be socially constructed, they continue to use them enthusiastically as if they represented well-defined, homogeneous groups of people. Think of the controversies over college admissions, disparities in academic achievement, or ethnic studies curricula.

The problems with grouping students in terms of contemporary racial categories are most evident — and most instructive — in how we interpret their academic performance, especially on standardized tests like the ACT. I’ve argued (here, here, and here) that racial categories are virtually useless in explaining student performance differences because the categories are largely arbitrary, often contrived, and always confounded by self-reporting biases and socio-economics. Nonetheless, a race-based narrative continues to dominate our discussions despite the fact that thinking in those terms perpetuates a host of inaccurate, deleterious stereotypes.

The ACT is a standardized test that predicts the likelihood of student success in the first year of college. The overall score is based on the results of four, multiple-choice subject tests, English, math, reading, and science. The number of correct answers for each subject test is converted into a scaled score and averaged. Thirty-six is perfect.

In 2022, approximately 1.35 million students took the ACT. Overall, the average score was 20, about one point lower than the average between 1990 and 2021. In terms of the ACT’s racial categories, the highest 2022 scores were earned by students identifying as Asian (25), White (21), and Two or More Races (20). The next three groups were Hispanic/Latino, Prefer Not to Respond/No Response, and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (18). The two lowest-performing groups were American Indians/Alaskan Native, and Black/African-American (16).

This ranking by race has remained virtually unchanged for a decade, and when viewed in terms of these categories, the ranking seems to support the divisive and inaccurate belief that the test is racially discriminatory. However, there are two problems with viewing the scores in this way. First, it’s impossible to know exactly how students sort — or choose not to sort — themselves into racial categories, and there is no way of knowing the ethnicity of those in the Two or More Races (first introduced in 2012), or the Prefer Not to Respond groups.

Second, the categories, themselves, have always been somewhat arbitrary. For instance, in 2012, the ACT separated the so-called, Asian-American/Pacific Islander category into two cohorts that turned out to be completely different in their test performances. In that year, there was a 13% increase in the number of students in the Asian group, and a 12% decrease in the number of Pacific Islanders who met the ACT’s College Readiness Benchmarks compared to 2006. That remarkable divergence has continued. Since 2012, the Asian group’s ACT scores have steadily improved while all other groups have steadily declined. This clearly demonstrates that the original Asian-American/Pacific Islander group was a demographic of convenience with little external validity and which masked dramatic within-group differences. Further, because the two newly created groups are so diverse, it would be virtually impossible to determine precisely why the group performances are so different. Assuredly, the same thing would happen if any of the other racial categories were similarly subdivided.

Then, in 2006, the ACT began analyzing student scores in terms of Postsecondary Educational Aspiration (what students planned to do after graduation). This parameter included seven categories: Vocational-Technical Training, Two-Year College Degree, Bachelor's Degree, Graduate Study, Professional-Level Degree, and two which I won’t consider here, Other and No Response. When the data are considered in terms of these categories rather than race, a very different picture emerges.

In 2006, 2012, and 2022, across all racial groups, ACT scores were 31-51% higher for students aspiring to a professional-level degree compared to students planning on vocational-technical training, and scores were 12-17% higher for those aspiring to a graduate degree compared to a bachelor's degree.

The effects of postgraduate aspirations have been even more dramatic within racial groups every year since 2006. For instance, in 2022, students in every category who aspired to a professional-level degree had ACT scores averaging 47% higher than those planning on vocational-technical training. The largest differences — 53% and 61% — were in the Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander and Prefer Not to Respond/No Response groups. The smallest (but still significant) difference — 35% — was in the American Indian/Alaska Native group.

More importantly, in 2022, students in the four (overall) lowest-performing racial groups who aspired to graduate study or a professional-level degree earned scores as much as 39% higher than students in the (overall) highest-performing groups who aspired to vocational-technical training or a two-year college degree. In other words, Black, American Native, Hispanic, and Hawaiian/Pacific Islander students with high educational aspirations outscored Asian, White, multiracial, and non-identifying students with lower aspirations.

Unfortunately, no one seems to have noticed that aspirations are more important than race in predicting academic performance on the test. I guess that doesn’t fit the popular narrative.

Over the past 15 years, educational aspirations have consistently had a greater impact on ACT performance than self-reported race. This suggests that by doing what we can to elevate student aspirations, irrespective of their race, we will benefit their academic performance. One way to do this is by teaching students that they can and will succeed if they work hard, rather than telling them that they are at the mercy of uncontrollable external circumstances. This will also give the lie to the worn out, race-based tropes about academic performance that are so psychologically damaging to students.

As a Biological Psychologist — and someone who taught standardized test prep for over a decade — I understand that the factors influencing student performance are complex and often the result of long-term trends that vary within and between groups, regardless of how the groups are defined. However, using anachronistic, ambiguous, or contrived racial categories to interpret educational performance is misleading, unhelpful, and divisive.

Racial categories have external validity only to the extent that each represents a meaningfully homogenous and distinct group of people. However, none of these criteria are met by the colloquial categories currently applied to people. Distinguishing students by, for instance, family or socioeconomic demographics, internalized cultural beliefs, personality traits (such as resilience or aspirations), school district, or ZIP code would all be more informative and useful in improving educational policy than the current crude racial categories. Further, to paraphrase Ferrero, refocusing our conversation on aspirations — rather than on our perceived ethnicity — will help us bridge our imagined racial differences, recognize our shared humanity, and encourage us to pursue our goals together.

==

@madwriterscorner You might find this interesting.

This demonstrates the problem with univariate takes, like those of Kendi, whose entire academic output sits precariously atop the fallacy of Causal Reductionism and his complete lack of interest in understanding a problem before pretending he does.

#Frederick R. Prete#FAIR for All#Foundation Against Intolerance and Racism#standardized testing#ACT test#American College Testing#antiracism#antiracism as religion#religion is a mental illness

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gender Identity and Diversity

Written for and published originally by The Daily Oklahoman, 2022

Recently, the topic of gender identity and diversity has received some negative air time. There has been some general disagreement in the public due to inaccurate rhetoric about what gender is, how it functions, and why it is significant. And many people have not received an adequate gender education to dispute false claims, so these inaccurate claims only grow and mutate. Something so personal as gender is rightly bound to be political, but is then impractical to legislate or regulate. And there lies the issue that many people have with gender diversity, it cannot be regulated. So, gender diversity is often rejected. I urge readers that are still unsure about how they feel about gender identity and diversity, or perhaps want to learn more, to read this piece and do some self reflection about how they define their own gender.

But what really is gender, if it is not sex? Gender is an expression of one’s social, personal, and political identity through their relationships with masculinity and femininity. Gender has also been defined by a leading gender theorist, Judith Butler, as a “stylized repetition of acts.” People are defined by patterns in behavior, habits, and thoughts. Although personal, gender is strictly regulated by law and through the perpetuation of social norms. Think to yourself for a moment, have you ever noticed how at gender reveal parties, the sex of the baby is often symbolically replaced by a color? That is an accessible example of a gender norm: Pink is for girls and blue is for boys. It is my belief as a highly educated and open-minded person, that gender is far more complicated than that.

Through many pieces of proposed legislation, press releases, and even social media posts, the very idea of gender as personal has been discredited. The idea that your gender is yours, belongs to you, and is a reflection of your self-image is not very popular in dominant American discourse, especially when that means that the possibilities are endless and not generalizable. When something cannot be generalized or defined for the masses in law, it tends to make people uncomfortable and their thoughts flood with big “what ifs'' about gender that often stem from a lens of gender-based crime. However, restricting the human rights of a minority group from a place of misunderstanding, is not a sustainable solution to a problem with diversity or crime.

On the other hand, allowing people to exist and self-define in creative, non-restrictive ways could lead to a higher rate of community participation and economic development, an increase in the quality of life, specifically for LGBTQ+ people, and a reduced rate of suicidal ideation in the LGBTQ+ community. Furthermore, the current sex-linked, binary system of gender does not account for intersex people, whom are much more common than you think (1 in 2,000 to be exact, which roughly equates to about the same percentage of people with red hair).

Being intersex means that one’s chromosomes and/or sex phenotypes do not reflect either side of the sex binary, neither male (XY) nor female (XX). This group of people often undergo invasive medical procedures as infants to alter their sex organs, and some people live their lives completely unaware of their true sex identity. This is truly an injustice. So, if the gender binary leaves out 1 in 2,000 people, why do we still swear by it? This brings us to the idea of gender as a spectrum.

The concept that some people do not conform to binary gender at all, often loses momentum in the political arena because it can be seen as a threat to natural order. But, with intersex and even transgender people in mind, we cannot neatly define in law the unlimited ways gender can be expressed, unencumbered by one’s sex identity. If every person has the autonomy to dress themselves and behave in ways that reflect personal values, why do we not allow these same people to use more descriptive words to define their self concept? Why does gender have to be limited to one word or the other (man or woman)? Furthermore, why do we represent every person on earth with divergent sexual or gender identities with one acronym? This creates an “us” against “them” complex which is more divisive than helpful.

The LGBTQAI+ acronym is mosaic; It represents a span of many identity groups that have vastly different experiences, different identity performances, and different needs. Generalizing such a diverse group is an impossible task that we are reminded of each time a new letter is added. This acronym is made up of all types of people that have different cultural, racial, and sexual identities and abilities. Yet, we still lump them together because they are all similarly “different.” This is something I want you to really think about: What truly separates you from your queer neighbors? My guess is, not much.

I have dedicated my personal and academic life to the study of gender, so I have given this topic more thought than most. The one thing I wish more people understood about gender identity is how freeing it should feel. When we are granted the agency to self-define, we ought to seize it and maintain full power over our self presentations. People already self define in creative ways such as abbreviating a birth name, like changing Charlette to Charlie. But why do we draw the line there for queer people?

I changed my name socially about seven years ago, but I still get the question “...but what is your real name?” when I introduce myself. A question like that undermines and polices the authority I have over my own life. Think about it. I am pretty sure I have the capacity to know my name and share it appropriately when asked, just like everyone else. So why question the identity of any other person, unless you do not find them to be personally credible? If you find yourself questioning someone in that manner, ask yourself, “What do I have to believe that they are not credible?

Perhaps it is because queer people challenge the dominant social structures under which we live, and that can be scary. I am a non-binary person and my gender is untethered from social norms because I exist outside of the binary we are ruled by. To some, it may seem like I am bending the rules of our social contract. In reality, I am using personal agency and power to govern the rules of my own life. Most people would agree that personal power is important. Doesn't sound so bad when it's put like that, does it?

_____________________________

SOURCES:

Butler, J. (1988). Performative acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist Theory. Theatre Journal, 40(4), 519. https://doi.org/10.2307/3207893

Badgett, M. V. L., Nezhad, S., Waaldijk, K., & Rodgers, Y. van der M. (2014). Linking LGBT Inclusion and Economic Development. In The Relationship between LGBT Inclusion and Economic Development: An Analysis of Emerging Economies (pp. 13–19). The Williams Institute at UCLA School of Law. http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep35047.6

Flores, A. R. (2019). INTRODUCTION. In SOCIAL ACCEPTANCE OF LGBT PEOPLE IN 174 COUNTRIES 1981 TO 2017 (pp. 4–7). The Williams Institute at UCLA School of Law. http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep35024.4

Cottrell, D. B., Gonzalez, J. D., Atchison, P. T., Evans, S. C., & Stokes, A. (2022). Suicide risk and prevention in LGBTQ+ youth. Nursing, 52(2), 40–45. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.nurse.0000803432.31284.34

How common is intersex? Intersex Society of North America. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://isna.org/faq/frequency/

What is intersex? Frequently Asked Questions. interACT. (2022). Retrieved from https://interactadvocates.org/faq/#whatis

1 note

·

View note

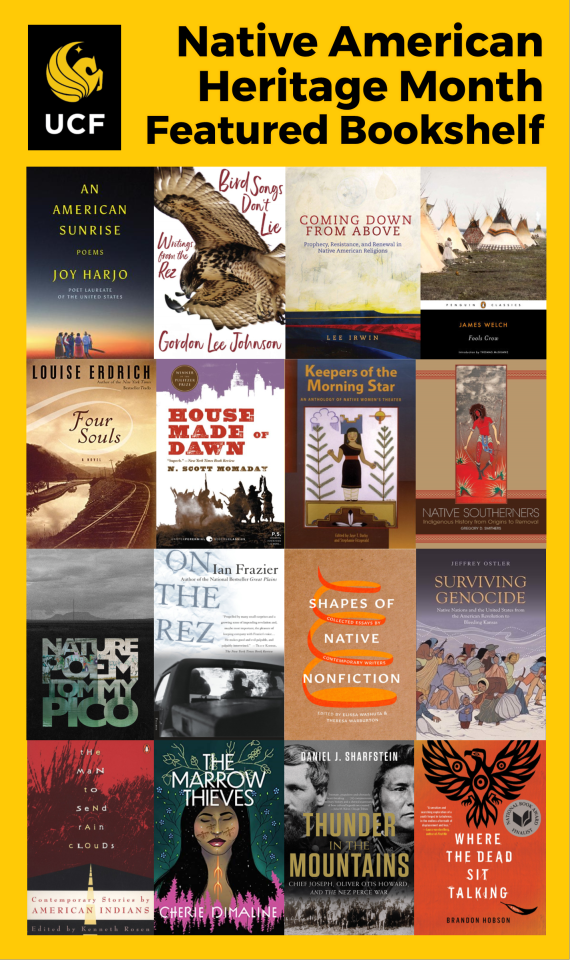

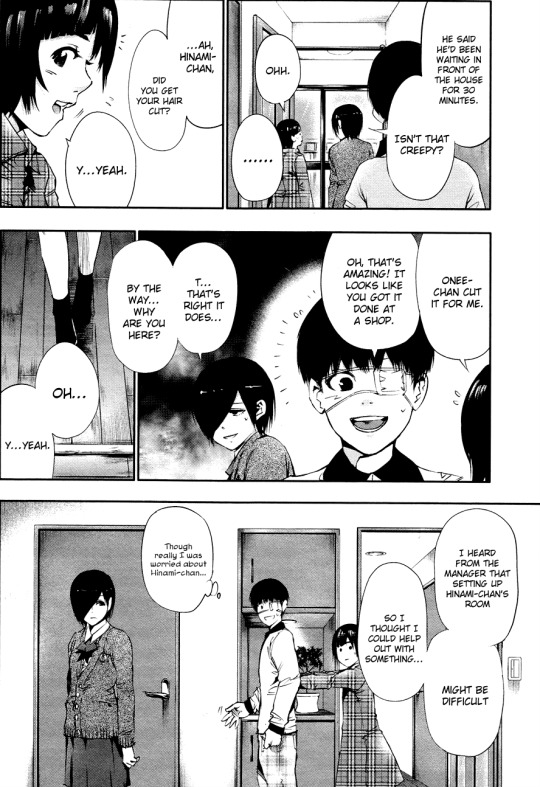

Photo

November in the United States is Native American Heritage Month, also referred to as American Indian and Alaska Native Heritage Month. It celebrates the rich history and diversity of America’s native peoples and educates the public about historical and current challenges they face. Native American Heritage Month was first declared by presidential proclamation in 1990 which urged the United States to learn more about their first nations.

Join the UCF Libraries as we celebrate diverse voices and subjects with these suggestions. Click on the Keep Reading link below to see the full list, descriptions, and catalog links for the featured Native American Heritage titles suggested by UCF Library employees. These 16 books plus many more are also on display on the 2nd (main) floor of the John C. Hitt Library next to the bank of two elevators.

An American Sunrise by Joy Harjo

In the early 1800s, the Mvskoke people were forcibly removed from their original lands east of the Mississippi to Indian Territory, which is now part of Oklahoma. Two hundred years later, Joy Harjo returns to her family’s lands and opens a dialogue with history. In An American Sunrise, Harjo finds blessings in the abundance of her homeland and confronts the site where her people, and other indigenous families, essentially disappeared. From her memory of her mother’s death, to her beginnings in the native rights movement, to the fresh road with her beloved, Harjo’s personal life intertwines with tribal histories to create a space for renewed beginnings. Her poems sing of beauty and survival, illuminating a spirituality that connects her to her ancestors and thrums with the quiet anger of living in the ruins of injustice.

Suggested by Sara Duff, Acquisitions & Collections

Bird Songs Don't Lie: writings from the rez by Gordon Lee Johnson

In this deeply moving collection of short stories and essays, Gordon Lee Johnson (Cupeño/Cahuilla) cements his voice not only as a wry commentator on American Indian reservation life but also as a master of fiction writing. In Johnson's stories, all of which are set on the fictional San Ignacio reservation in Southern California, we meet unforgettable characters like Plato Pena, the Stanford-bound geek who reads Kahlil Gibran during intertribal softball games; hardboiled investigator Roddy Foo; and Etta, whose motto is “early to bed, early to rise, work like hell, and advertise,” as they face down circumstances by turns ordinary and devastating. From the noir-tinged mystery of “Unholy Wine” to the gripping intensity of “Tukwut,” Johnson effortlessly switches genre, perspective, and tense, vividly evoking people and places that are fictional but profoundly true to life.

Suggested by Megan Haught, Research & Information Services/Teaching & Engagement

Coming Down from Above: prophecy, resistance, and renewal in Native American religions by Lee Irwin

An introduction to an important strand within the rich tapestry of Native religions, this shows the remarkable responsiveness of those beliefs to historical events. It is an unprecedented, encyclopedic sourcebook for anyone interested in the roots of Native theology. From the highly assimilated ideas of the Puget Sound Shakers to such resistance movements as that of the Shawnee Prophet, Irwin tells how the integration of non-Native beliefs with prophetic teachings gave rise to diverse ethnotheologies with unique features. He surveys the beliefs and practices of the nation to which each prophet belonged, then describes his or her life and teachings, the codification of those teachings, and the impact they had on both the community and the history of Native religions. Key hard-to-find primary texts are included in an appendix.

Suggested by Sandy Avila, Research & Information Services

Fools Crow by Thomas E. Mails; assisted by Dallas Chief Eagle

Set in Montana shortly after the Civil War, this novel tells of White Man's Dog (later known as Fools Crow so called after he killed the chief of the Crows during a raid), a young Blackfeet Indian on the verge of manhood, and his band, known as the Lone Eaters. The invasion of white society threatens to change their traditional way of life, and they must choose to fight or assimilate.

Suggested by Mary Lee Gladding, Circulation

Four Souls: a novel by Louise Erdrich

After taking her mother’s name, Four Souls, for strength, the strange and compelling Fleur Pillager walks from her Ojibwe reservation to the cities of Minneapolis and Saint Paul. She is seeking restitution from and revenge on the lumber baron who has stripped her tribe’s land. But revenge is never simple, and her intentions are complicated by her dangerous compassion for the man who wronged her.

Suggested by Jada Reyes, UCF Libraries Student Ambassador

House Made of Dawn by N. Scott Momaday

He was a young American Indian named Abel, and he lived in two worlds. One was that of his father, wedding him to the rhythm of the seasons, the harsh beauty of the land, the ecstasy of the drug called peyote. The other was the world of the twentieth century, goading him into a compulsive cycle of sexual exploits, dissipation, and disgust. Home from a foreign war, he was a man being torn apart, a man descending into hell.

Suggested by Mary Lee Gladding, Circulation

Keepers of the Morning Star: an anthology of native women's theater edited by Jaye T. Darby and Stephanie Fitzgerald

This is the first major anthology of Native women's contemporary theater bringing together works from established and new playwrights. This collection, representing a rich diversity of Native communities, showcases the exciting range of Native women's theater today from the dynamic fusion of storytelling, ceremony, music and dance to the bold experimentation of poetic stream of consciousness and Native agitprop.

Suggested by Rich Gause, Research & Information Services

Native Southerners: indigenous history from origins to removal by Gregory D. Smithers

Long before the indigenous people of southeastern North America first encountered Europeans and Africans, they established communities with clear social and political hierarchies and rich cultural traditions. Award-winning historian Gregory D. Smithers brings this world to life in Native Southerners, a sweeping narrative of American Indian history in the Southeast from the time before European colonialism to the Trail of Tears and beyond.

Suggested by Megan Haught, Research & Information Services/Teaching & Engagement

Nature Poem by Tommy Pico

This work follows Teebs―a young, queer, American Indian (or NDN) poet―who can’t bring himself to write a nature poem. For the reservation-born, urban-dwelling hipster, the exercise feels stereotypical, reductive, and boring. He hates nature. He prefers city lights to the night sky. He’d slap a tree across the face. He’d rather write a mountain of hashtag punchlines about death and give head in a pizza-parlor bathroom; he’d rather write odes to Aretha Franklin and Hole. While he’s adamant―bratty, even―about his distaste for the word “natural,” over the course of the book we see him confronting the assimilationist, historical, colonial-white ideas that collude NDN people with nature. The closer his people were identified with the “natural world,” he figures, the easier it was to mow them down like the underbrush. But Teebs gradually learns how to interpret constellations through his own lens, along with human nature, sexuality, language, music, and Twitter. Even while he reckons with manifest destiny and genocide and centuries of disenfranchisement, he learns how to have faith in his own voice.

Suggested by Sara Duff, Acquisitions & Collections

On the Rez by Ian Frazier

This is a sharp, unflinching account of the modern-day American Indian experience, especially that of the Oglala Sioux, who now live on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in the plains and badlands of the American West. Crazy Horse, perhaps the greatest Indian war leader of the 1800s, and Black Elk, the holy man whose teachings achieved worldwide renown, were Oglala; in these typically perceptive pages, Frazier seeks out their descendants on Pine Ridge―a/k/a "the rez"―which is one of the poorest places in America today.

Suggested by Larry Cooperman, Research & Information Services

Shapes of Native Nonfiction by Elissa Washuta

Just as a basket's purpose determines its materials, weave, and shape, so too is the purpose of the essay related to its material, weave, and shape. Editors Elissa Washuta and Theresa Warburton ground this anthology of essays by Native writers in the formal art of basket weaving. Using weaving techniques such as coiling and plaiting as organizing themes, the editors have curated an exciting collection of imaginative, world-making lyric essays by twenty-seven contemporary Native writers from tribal nations across Turtle Island into a well-crafted basket.

Suggested by Sara Duff, Acquisitions & Collections

Surviving Genocide: native nations and the United States from the American Revolution to bleeding Kansas by Jeffrey Ostler

An authoritative contribution to the history of the United States’ violent path toward building a continental empire, this ambitious and well-researched book deepens our understanding of the seizure of Indigenous lands, including the use of treaties to create the appearance of Native consent to dispossession. Ostler also documents the resilience of Native people, showing how they survived genocide by creating alliances, defending their towns, and rebuilding their communities.

Suggested by Megan Haught, Research & Information Services/Teaching & Engagement

The Man to Send Rain Clouds: contemporary stories by American Indians edited by Kenneth Rosen

Over a two-year period, Kenneth Rosen traveled from town to town, pueblo to pueblo, to uncover the stories contained in this volume. All reveal the preoccupations of contemporary American Indians. Not surprisingly, many of the stories are infused with the bitterness of a people and a culture long repressed. Several deal with violence and the effort to escape from the pervasive, and so often destructive, white influence and system. In most, the enduring strength of the Indian past is very much in evidence, evoked as a kind of counterpoint to the repression and aimlessness that have marked, and still mark today, the lives of so many American Indians.

Suggested by Rich Gause, Research & Information Services

The Marrow Thieves by Cherie Dimaline

Humanity has nearly destroyed its world through global warming, but now an even greater evil lurks. The indigenous people of North America are being hunted and harvested for their bone marrow, which carries the key to recovering something the rest of the population has lost: the ability to dream. In this dark world, Frenchie and his companions struggle to survive as they make their way up north to the old lands. For now, survival means staying hidden … but what they don’t know is that one of them holds the secret to defeating the marrow thieves.

Suggested by Mary Lee Gladding, Circulation

Thunder in the Mountains: Chief Joseph, Oliver Otis Howard, and the Nez Perce War by Daniel J. Sharfstein

Recreating the Nez Perce War through the voices of its survivors, Daniel J. Sharfstein’s visionary history of the West casts Howard’s turn away from civil rights alongside the nation’s rejection of racial equality and embrace of empire. The conflict becomes a pivotal struggle over who gets to claim the American dream: a battle of ideas about the meaning of freedom and equality, the mechanics of American power, and the limits of what the government can and should do for its people. The war that Howard and Joseph fought is one that Americans continue to fight today.

Suggested by Sandy Avila, Research & Information Services

Where the Dead Sit Talking by Brandon Hobson

With his single mother in jail, Sequoyah, a fifteen-year-old Cherokee boy, is placed in foster care with the Troutt family. Literally and figuratively scarred by his mother’s years of substance abuse, Sequoyah keeps mostly to himself, living with his emotions pressed deep below the surface. At least until he meets seventeen-year-old Rosemary, a troubled artist who also lives with the family. Sequoyah and Rosemary bond over their shared Native American background and tumultuous paths through the foster care system, but as Sequoyah’s feelings toward Rosemary deepen, the precariousness of their lives and the scars of their pasts threaten to undo them both.

Suggested by Rich Gause, Research & Information Services

623 notes

·

View notes

Text

Week #11 Blog Post due 11/04/20:

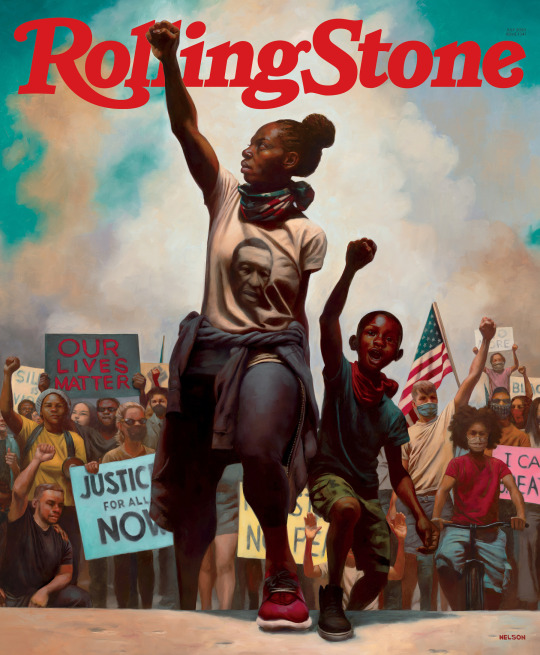

What influence does the mainstream media play in how black victims of police brutality are depicted?

“Days following the deaths of Garner and Brown, news reports of the incidents characterized Brown as a thug, gang member, and lawbreaker. Garner was characterized as a repeat offender with news reports discussing his criminal history. News reports also made reference to the height and body size of both Brown and Garner, using fear-mongering labels such as ‘giant’ and ‘huge’ to make Brown and Garner seem superhuman, dangerous, and therefore needing to be tamed.” (Lee, 2017). Mainstream media takes an innocent black individual and draws them out as the enemy, the one to blame, dangerous and “needing to be tamed”, finding the smallest of details from their lives and amplifying it through a negative lens to justify the use of force and police brutality. Cops are put in place to deescalate situations. Even if an individual is found guilty, cops do not play the role of executioner, jury or judge. Mainstream media forgets that when it comes to black lives. They find any reason or image to justify the cops’ abuse of power towards the black community and paint the individual as a ‘thug’, threat, danger, and criminal. Mainstream media enables cops and the law to further feed into this idea that it’s okay to kill black people if cops feel threatened. Mainstream media enables our society to be okay with this behavior from cops who are meant to protect us— not create fear in communities and kill innocent lives through the use of force and illegal tactics. Mainstream media adds gasoline to the fire that already exists in the tension between cops and black communities.

What is ‘Black Twitter’ and ‘blacktags’ as described in the reading, “Black Twitter: A Response to Bias in Mainstream Media”?

The term ‘Black Twitter’ refers to the black community present on Twitter. Blacktags refers to: “Building on this concept, this article is interested in the textual poaching that occurs in social media, specifically black Twitter, for purposes of challenging and resisting dominant degrading narratives placed on black and brown bodies through mainstream news coverage...She argues that black Twitter’s power comes from its participatory democratic nature—the idea that users, through the creation of ironic, yet cutting-edge hashtags, create a space to address social issues of racial bias and discrimination. Indeed, this forum allows for textual poaching as resistance, where the user produces content that challenges dominant (oppressive) cultural ideologies and norms, including racial bias” (Lee, 2017). This is an act of demanding justice where justice is lacking or not present. This is an effective response through the use of hashtags to inform and expose the injustices that the black community is constantly facing socially, economically, politically, educationally, culturally, and overall any possible aspect. Through blacktags, Black Twitter draws out the oppression and racism that still exists against them and their entire community. This is a smart and strategic way in utilizing social media platforms to create conversation where progress and fixing is very much needed. Through the use of twitter, information and voices are amplified and spread at a significant speed, making action follow faster than it normally would.

How can one be an active ally to people of color, particularly the black community?

“Ross shared his own story of ‘criming while white’ to mark the racialized double-standard of our criminal justice system, and encouraged other white folks to share their stories...this hashtag, which was named one of the most trending hashtags for 2014, demonstrated an unequal justice system and a racial double standard…[An example provided being:] When I was 20, I stole a pack of cigs, cop prayed with me and made me promise I wouldn’t do it again. #CrimingWhileWhite..” (Lee, 2017). People get uncomfortable when it's time to talk about racism and white privilege, but the time to talk about it is now, even when we don’t know how to get started. Getting the conversation going is the first step to creating a voice, community, and action in fighting for true justice for all. One can not say they are not racist and stay silent about the issues that black communities are currently facing. It is especially our responsibility to dismantle the structure and systems we currently have in place that strive off the oppression of the black community. The incarceration of the black community is a huge example of modern day slavery, the acts of inhumanity and violence towards them is an example of racism, hate, white supremacy and oppression that is still very much alive in our country and all over the world. To be an ally, we must use our privilege to speak and amplify what it is they are demanding, equality and humanization, equal opportunities, equity, and overall respect of their entire existence and identity, to acknowledge their suffering and to most importantly, listen. It is not our place to speak for them, but rather to share their stories, hear them out, and fight against injustices happening every single day.

What are some positive benefits that can be obtained through internet activism?

“Public awareness is achieved by accessing information that is relevant to the cause. Naturally there is often difficulty involved. Since the traditional information channels may well be controlled by those whose interest is counter to that of the activists, the Internet may serve as an alternative news and information source. The news and information are provided by individuals and independent organizations, largely focusing on events and issues not reported, underreported, or misreported in the mainstream mass media. The forms of obtaining information include visiting relevant Web sites or participating in different types of email distribution lists.” (Veghs, 2003). Through internet activism, as I stated earlier, information travels at a significant speed, making it faster and easier for information to travel across the world and form communities that share the same goal and values. This creates a sense of unity for some communities where it may be harder to find that overall safe space offline. The internet allows for many opportunities to arise with the use of forming and planning events such as protests, creating and participating in signing petitions, creating groups, sharing stories and overall posts with a message and purpose. Internet activism, if done right and being aware of falling into slacktivism, it can create widespread and rapid change if enough people are able to amplify the message, and with the internet, it is much faster and easier to bring this level of awareness to issues and problems that our country is currently facing— whether it be a hashtag, a headline, a post, or group messages. All of these are a few examples of the benefits that internet activism could provide for some communities in getting stuff done at a faster and widespread rate.

Fuchs, C. (2004). Social media and communication power. In social media: A critical introduction (pp. 69-94). London: Sage Publications Ltd. doi:10.4135/9781446270066.n4

Lee, L. (2017). Black Twitter: A Response to Bias in Mainstream Media. Social Sciences, 6(1), 26. doi:103390/socsci6010026

Vegh, S. (2003). Classifying Forms of Online Activism: The Case of Cyberprotests against the World Bank.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

10-Ways To Be Anti-Racist

1) Hold your friends and family accountable. Challenge yourself to engage in respectful conversation with people close to you when they make problematic comments by actively listening and utilizing the E.A.R.S strategies (credit: Dr. Kathy Obear). -Explore, inquire and ask questions(s) -Acknowledge their feelings -Restate what they said to check for accuracy -Exploring Solutions together

2) Attend workshops, events, conferences, and protests that focus on race-related issues. Conduct research on local non-profit organizations to locate resources and opportunities to engage. Many of these events are free and open to the public!

3) Diversify your knowledge and check your information bias. Subscribe to newsletters from nonprofits focused on racial equality and diversify your news outlets to include different viewpoints, ideologies, etc. Utilize different resources (i.e. educational videos, news articles) with more nuanced analysis through a lens of race/ethnicity, including updates and action steps.

4) Engage in race and ethnicity courses through different course or educational sessions. Take race and ethnicity focused courses outside what is required for your major or area of study. Engaging in classes you wouldn’t otherwise take allows you to gain more-in-depth perspectives and knowledge of current racial disparities through history exploration, contemporary issues, and theory.

5) Have intentional conversations with peers, friends, co-workers, etc. with respect to each other’s boundaries. Step out of your comfort zone to engage in conversations that challenge the way you see the world by exchanging stories and sharing different perspectives. Learning about other people’s lived experiences can broaden your preconceived notion of racial issues.

6) Learn with humility. Try to practice active listening by listening to understand rather than listening to respond. When you choose to engage, do not assume you know or understand the experiences of marginalized communities, especially those you do not identify with. If people share their experiences with you, be sure to affirm and validate their experiences while being cautious of the space you are occupying.

7) Support the work, art, and businesses of people of color. Institutional and systemic barriers have led to a lack of representation and support for many marginalized communities in mainstream media, politics, and organizations. It is important to champion their work in movies, art shows, books, and music by promoting it on social media, purchasing their materials, and recognizing their contributions to their respective industries.

8) Become involved in organizations that support racial justice issues. Locate organizations that are working within communities to enhance the lives of those disproportionately affected by racism. Support them by donating money (if possible), volunteering time, or spreading awareness of their mission.

9) Avoid usage of stereotypical and normalized, microaggressive comments. Examples include: -“Where are you really from?” -“What are you?” -“You sound white” or “You’re really well-spoken.” -“I don’t really see you as Indian.” -“You have really big eyes for an Asian person.”

10) During a national crisis, such as the Covid-19 pandemic, do not scapegoat certain racial and/or ethnic groups for the crisis. Blaming entire communities for crises can lead to increased violence and overt discrimination towards the targeted group(s). Remember that the U.S. consists of a diverse group of people and one's race/ethnicity and/or skin color does not determine one’s claim to being American. Recognizing the racism behind certain comments or actions will allow you to become a better ally to the targeted group(s).

From Michigan University

1 note

·

View note

Text

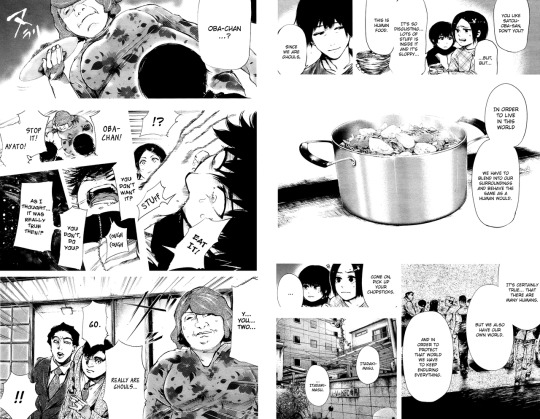

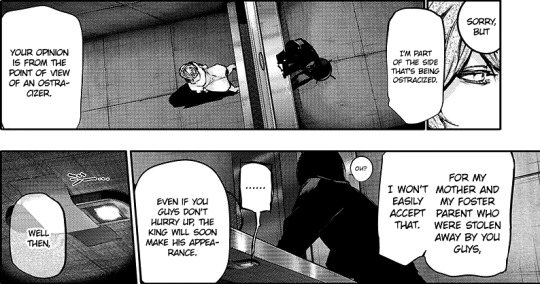

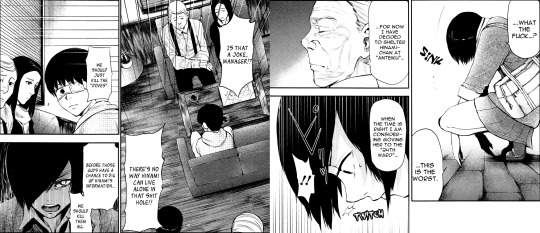

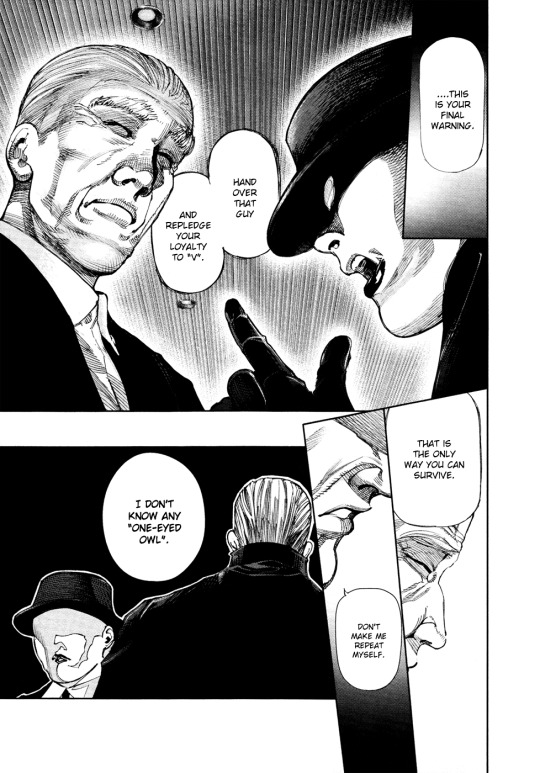

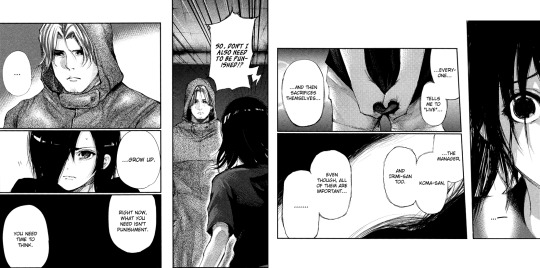

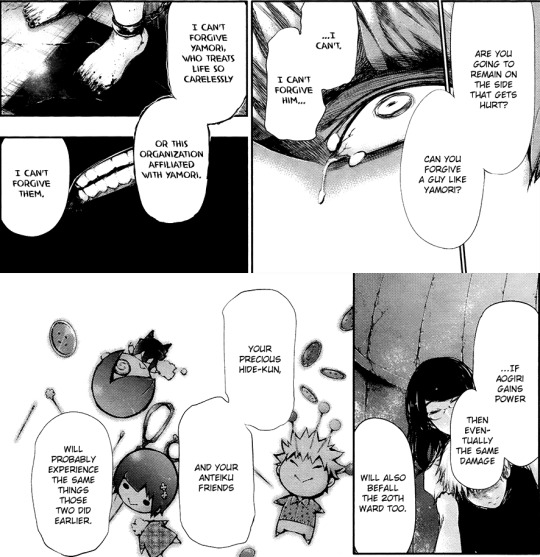

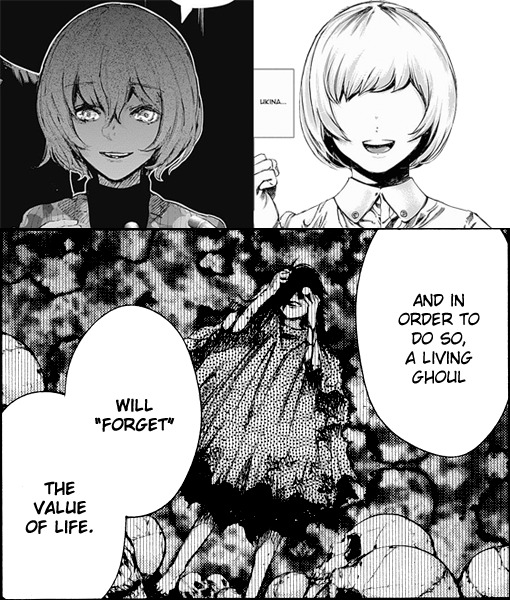

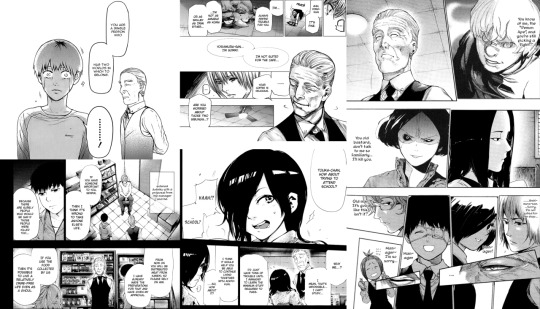

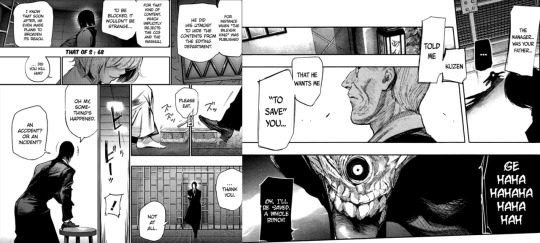

Touka and Kuzen - contrasting managerial styles

TG 143

I wanted to take a look at Touka and Kuzen through the lens of how they handled situations differently, and how they handled their creations of cafes for their loved ones. It’s well known that Touka’s creation of ;re paralleled Kuzen’s creation of Anteiku. However, Ishida goes out of his way to show the immense differences between these two characters. This difference, and how it came to be, is portrayed in their backstories, and how they carry themselves in the actual story. This post will cover things in both TG and TG;re.

So, to start with, we’ll cover Touka’s backstory. Then, we’ll cover Kuzen’s backstory. Then, we’ll note the difference between these two characters, how it shows in their backstories, how it shows in their characters, so on and so forth.

TG;re 71

Touka’s first encounter with tragedy is at a very young age. Her mother and father are engaged by Arima. While her mother holds them off, her father escapes with her and her brother. The loss of her mother leads her father to engage in ghoul cannibalism and developing a kakuja. Eventually, he ends up running into multiple ghoul investigators lead by Shinohara and Kureo Mado and is captured by them.

There are two versions of the stoy here - according to Yomo in TG;re 71, Arata was targeted for his power. Touka’s story in TG;re 120 is that her father was killing ghoul investigators; there, we learn she laments her father’s decisions, and blames herself for his actions.

TG 71, 70

Touka and Ayato end up being turned into the CCG by the very human neighbors their father encouraged them to trust, respect, and make sacrifices for. Touka is forced to kill one of the CCG agents that attempts to capture them as a result, and they flee.

TG 71, 70

Of course, before he left, her father instilled lessons on Ayato and her. These aren’t the only ones, of course but they are the ones we’ll be discussing. Before leaving, Arata instructs Ayato that he must keep his sister safe. For Touka, he instructs her that she must teach him about life. These are things that parents often say to their children, but it ends up taking on a different meaning for Touka and Ayato due to their childhood. Because of their circumstances, Touka ends up shouldering these burdens herself, quite literally, in the form of Ayato.

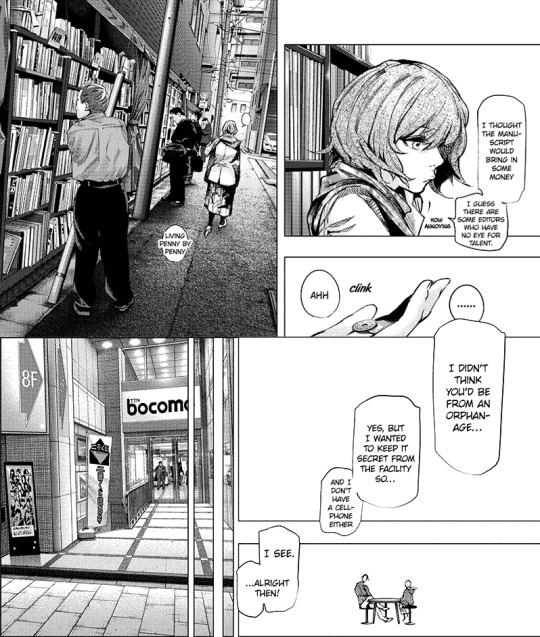

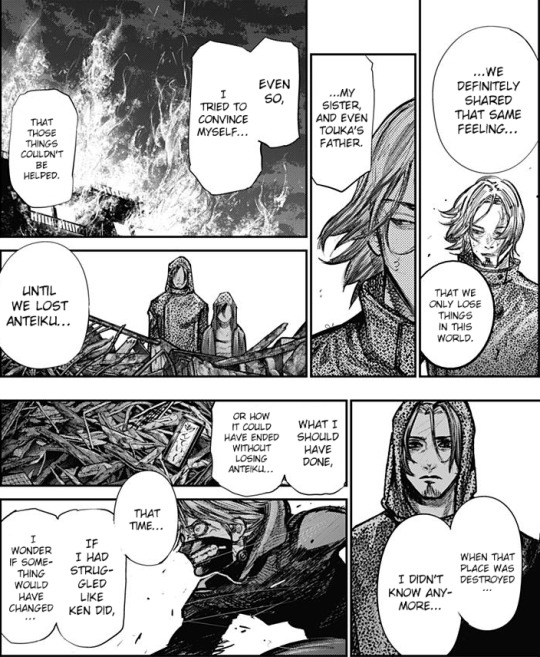

Now, lets talk Kuzen.

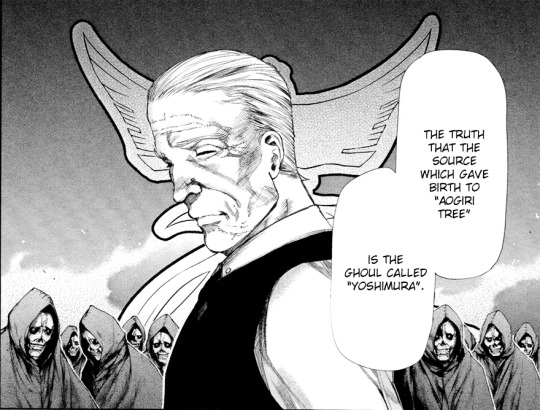

TG 119

Kuzen grew up completely alone. He never had anyone but himself to rely on - as a result, he ended up killing countless humans and ghouls. He started cannibalizing at a young age not for the reason that many other characters do - loss of others and the desire for strength - but instead because he wanted to live a long life and not go hungry (this is reminiscent of Roma’s backstory TG;re 135). Because of his strength and willingness to kill, he comes into contact with V. V provides him with food, shelter, and clothes, and in exchange, he continues what he’s already doing - killing. Kuzen’s needs in regards to safety, food shelter, and clothing are met. However, he feels unfulfilled.

The hierarchy of needs is not necessarily linear, but, generally speaking, it goes like this: human beings have physiological needs (eg food, water, shelter), safety needs (eg not fearing death), esteem needs (eg a career), social needs (eg love and family), and finally this leads to self actualization (eg fulfillment of one’s potential). Kuzen’s physiological, safety, and esteem needs are all being met by his employment by V. However, he still lacks loving and belonging. He still isn’t reaching his potential.

TG 119

And in comes Ukina, serving Kuzen coffee. Ukina was, according to Kuzen, an undercover journalist. The topic of her current story was V, the organization Kuzen worked for. Kuzen believes that Ukina was unaware of his status, as he was of hers, and that they happened upon one another. Eto provides a different version of the story - Ukina approaches her father because she’s aware he’s a member of V (TG;re 64).

Ukina is the first person Kuzen ever connects with intimately. She teaches him how to read the complex kanji he cannot understand. Through Ukina, Kuzen finds a place of belonging and higher fulfillment. Kuzen gets close to Ukina; she accepts him even after she finds out he’s a ghoul. Kuzen spares Ukina, and they eventually have a child together.

TG 119

Eventually Ukina’s objective is found out. Of course, V cannot let that stand. V orders Kuzen to kill Ukina. He does so, with Ukina’s last words being her remarks about his loneliness. One thing I want to note here is that, contrary to popular belief, Kuzen didn’t leave V. He simply stopped being part of their secret police. He just flat out says this, in much more polite words. That’s what “unable to cut ties” means. That’s why every time he goes to “work”, he’s wearing a V uniform. It’s why Kaiko can just walk right up to him later on in Tokyo Ghoul. There’s a reason why Eto was left in the 24th ward, after all.

This isn’t to say Kuzen didn’t make his own moves against V (such as sheltering Rize from their view), but that doesn’t mean he wasn’t a member still. All of the members of V are shown making moves against other members of V - eg, Kaiko, introduced as the face of V, helps Furuta kill the Washuus who are supposed to be higher ranking members of V. Arima and Furuta are both members of V and make their own moves against it. Matsuri also immediately considers members of V to likely be the culprit behind the attempt on his life. V in general is a very Darwinian organization that seems to compartmentalize and encourage, unintentionally or not, competition among its members as is common with authoritarian organizations.

Now that we’ve established these backstories before they began interacting in universe, lets take a look at how these two characters interact, and how they play off one another.

TG 71

There are substantial takeaways from these backstories, and what these characters actually value at heart. Kuzen’s story is a story of loneliness preceding tragedy - Touka’s story is a story of loneliness succeeding tragedy. Kuzen was always alone, but surviving. That is his state of being. It is what he knows. Touka’s situation was always with a family - making sacrifices to protect family, to survive with family. While both Kuzen and Touka ended up alone for a time, their actions and reactions are different.

It’s best encapsulated by Kuzen’s words to Touka after he hears of her and Ayato getting into a fight Tsukiyama, and splitting up once again. Kuzen’s words to Touka here aren’t exactly subtle - he’s not exactly being coy about implying Touka should prioritize herself over Ayato, by noting that fighting for family and food has its limits before mentioning Ayato’s violent tendencies. Kuzen then implies that Touka going for school and working at Anteiku would help her do better with Ayato. This makes no logical sense, however.

TG 71

The tragedy of Touka and Ayato was, from Ayato’s point of view, caused by humans. Arima took away their mother, followed by their father being taken away by Shinohara and Mado, followed by almost themselves being taken away by their own neighbors. They were betrayed by the very humans they suffered for at their fathers request. Touka is not only going to school with more humans, becoming friends with humans, she’s also spending time at Anteiku working as a human waitress, seving human customers, to pay Kuzen back. As a result, Ayato is being left alone, unchecked, and unguarded. Ayato gets upset and ends up running away, causing even greater chaos than he did when he was with Touka, and in much greater danger as a result.

This isn’t Touka’s fault. She’s a child herself in a very rough situations. Children running away from home isn’t uncommon, especially when they’re under stress and they feel they’re unappreciated and unloved, as Ayato does here. That doesn’t mean that he’s actually unappreciated or unloved, of course. The difference between a normal human teenager running from home, and Ayato running from home, is that Ayato’s family, in the form of Yomo and Touka, aren’t doing the smart thing and coming after him. They’re just letting him run rampant. Now, fortunately, this ends up working out for Ayato (YMMV) in that Aogiri Tree takes him in, rather than the CCG, or a rival ghoul gang that was angry at his attacks.

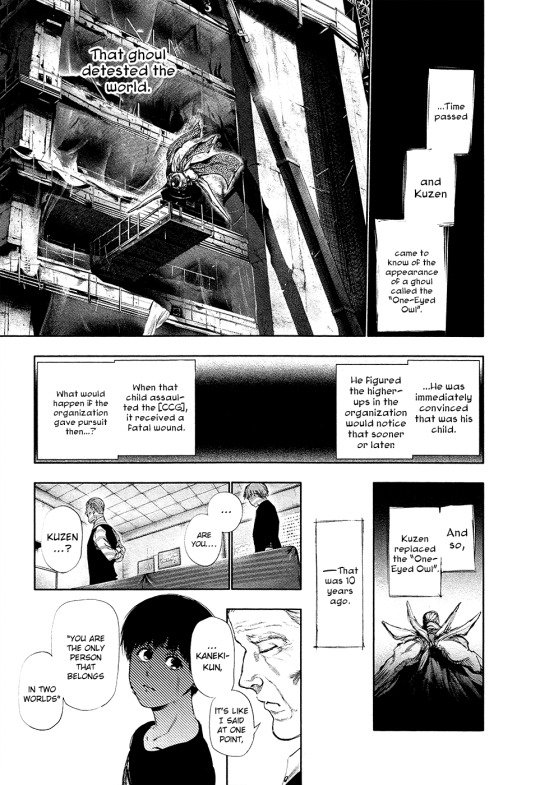

However, this is still the exact opposite thing that Kuzen intended. If it wasn’t for things that Kuzen couldn’t have predicted (eg Tatara), Ayato may very well have died. This is kind of a repeating pattern with him and it goes understated. So, before we go any further, lets go over his and Eto’s backstory again, before we get back to Anteiku.

TG 119

Ishida actually demonstrates how this plan failed, but lets go over this story, because there’s some obvious flaws with it.

So Kuzen leaves Eto in the one place that V will never find her. Inexplicably, Eto just comes out of nowhere, “filled with hatred of the world”, and decides to attack the CCG. During these attacks, she receives a lethal wound. Fearful that V might pursue Eto in addition to the CCG, Kuzen becomes Eto’s substitute and attacks a random CCG base, receiving a lethal wound himself.

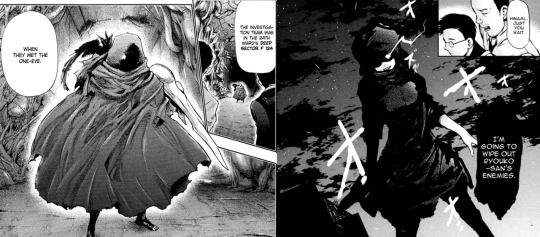

Okay, lets start with Eto’s motivation for her attacks. This is only going to be briefly covered, because the Eto/Touka parallels post covers this attack more thoroughly. Eto didn’t just pop up out of nowhere, as we know, she was actively being hunted by V and the CCG to begin with.

TG;re 66

Noroi ended up like Noro because V killed him. Shortly thereafter, as coincidence would happen, the CCG decided to do a “whack a mole” operation where they run into Eto at the specific coordinates they were sent to investigate in the deep section of the 24th Ward. It really can’t be stressed just how low the odds of this are.

TG;re 127, TG 80, TG 95

The Goat base in the middle of the 24th Ward in the D sector was 5 kilometers below the surface. The place they were attempting to escape to by going deeper was E14. Sector F124 is described as being part of the “deep”. We’re not given any reference points, and because V14 was just below the surface, it’s not necessarily linear. However, Eto was still located over 5 kilometers beneath the surface at the minimum.

The 24th Ward is a highly confusing, inconsistent labyrinth that is incredibly hard to navigate. And yet somehow, inexplicably, Marude’s team happen to run into Eto in the deep section they were sent to investigate. The implication here is that V failed their mission of killing Eto, and then tried to follow up with the CCG to kill Eto.

Why do I say the CCG’s battle with Eto occurred shortly after Noroi was killed? It’s simple.

TG;re 62

Noroi isn’t present with Eto when she is attacked by Marude’s team. You’d think that as her protector, he would be. Even Noro isn’t mentioned at any time for the original Owl campaign, despite being a known as a powerful fearsome ghoul of Aogiri. Eto’s also explicitly a penniless orphan right after her rebellion.

This is the first sighting of the One Eyed Owl and Eto cited both her mother’s death and Noroi’s death as a reason she cannot accept V, and Eto’s battle with Kasuka Mado is a parallel to Touka’s and Hinami’s fight against Kureo Mado, wherein Eto plays the part of both Hinami and Touka.

TG 124, 16

Eto didn’t just pop out of the abyss a fully formed kakuja that just hated the world. She didn’t even have a kakuja when she started her campaign, it’s shown as just a kagune. She was provoked by the the world controlling fascists that were intent on killing her and even went looking for her in the place that her father said would protect her from them to begin with. Kuzen knows, even after he “protected Eto”, that V was still pursuing her. We know this because he explicitly says so.

TG;re 71

So, lets move on to the part where Kuzen says he protects Eto. Eto receives a “lethal” wound…

TG;re 61

…that isn’t lethal to a kakuja one eyed ghoul. She literally lost an arm. It’s just damaging her combat ability to the point she was forced to run against multiple special class level investigators with reinforcements on the way. This type of injury is a non issue when it comes to “survival” to someone like Eto, who can, for example, be sliced in half and then chucked off the top of a skyscraper and survive. A ghoul’s regeneration is only stopped when their kahukou is severely damaged.

Then Kuzen takes her place without informing her or coordinating with her, and then also receives a “lethal” wound…

TG 69

And this somehow makes V and the CCG stop pursuing Eto because why, exactly? What changed here? If anything, shouldn’t the CCG and V be more enticed to go after the Owl, as it just received yet another supposedly lethal wound, if said lethal wound was really considered significant to begin with? It’s not like Kuzen immediately stepped in minutes after Eto received her wound and covered for her while she escaped. She explicitly escapes on her own.

Lets look at the logic here from two perspectives, one where Eto is in hiding and the CCG and V don’t know her identity, and one where she’s in hiding and they don’t.

If Eto was in hiding, and CCG and V didn’t know who or where she was, they wouldn’t be able to find her immediately to finish her off anyway. She’s in no immediate danger danger of being attacked as long as she’d not found. In that case, Kuzen’s attack is pointless. Actually, it’s less than pointless - it’s pinning an attack she had nothing to do with on her, and giving the CCG valuable anti-Owl experience to use against her due to the similarities of their kakujas.

If the CCG and V does know who she is, then it doesn’t matter if Kuzen attacks again. This attack doesn’t change the fact that, in this theoretical scenario, Eto’s identity has been exposed. Kuzen’s just getting into another fight that is pinned on Eto and changes nothing.

How does this stop Eto from going on the offensive again and running into V or the CCG? What’s stopping the CCG and V from going after Eto while Kuzen’s faking his attack? Now that Kuzen just ran into some random fight completely unrelated to Eto and received a “lethal” wound, how will he be able to help Eto if she is attacked? The answer is “it doesn’t do any of that”, because we know what ends up happening.

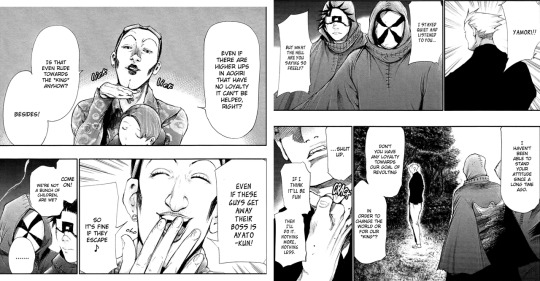

TG;re 86, 69, 52

Arima engaged Eto so close to the time frame that he engaged Kuzen, you can even see that Eto hasn’t even gotten enough time to regenerate her arm yet. Eto was made into a figurative quinque of Arima’s at the age of 14 because Kuzen’s attempt to protect her had no logical way of doing so.

TG 139

Because Arima wasn’t referring to a replacement for IXA here when he said he needed a quinque. Because Kaneki was not literally a quinque he went around killing ghouls with. Arima was referring to a new metaphorical quinque to replace an old one. The old one being Eto.

This isn’t fridge logic, this is something Kuzen should have thought about immediately, and it’s not like he didn’t have time. Kuzen says that he immediately knew that Eto was his child, and consider the description of the Owl campaign.

TG 69

Kuzen had months to think of a plan to help Eto. This was what he decided to do. Kuzen’s plan was liable to fail. It never made sense to begin with in any way, shape, or form to accomplish its goal to save Eto, and so of course it didn’t. Why would it? Kuzen’s not solving any of Eto’s problems - making her feel loved, actually protecting her, giving her guidance.

If it weren’t for Arima secretly hating V and his job, and Eto telling Arima she wants to “fix the world” she would have been killed. Eto survived because of Eto. Lets compare this to Touka, who was in a similar situation with Hinami

If you’re wondering “what should Kuzen have done?” the answer is to ask Touka, who actually succeeded at her goals.

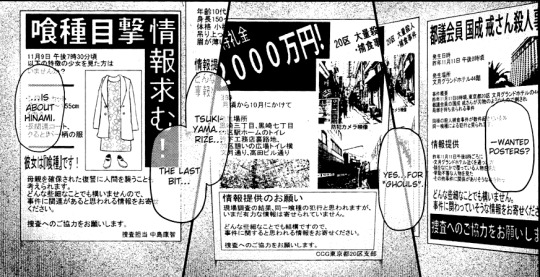

TG 23

I talked above how Volumes 2 and 3 of Tokyo Ghoul are effectively a parallel between Eto, and Touka and Hinami. It’s well known that Touka’s creation of ;re was meant as a parallel for Kuzen’s creation of Anteiku. There’s a reason for this. Lets take a look at how Touka handles the situations with Hinami and Kaneki that Kuzen’s also in, shall we?

TG 16

Kuzen left Eto in the 24th Ward. He tries to do the same with Hinami. Immediately, Touka gets enraged. You can’t just leave an orphaned 14 year old alone in the 24th Ward. The 24th Ward is considered one of the worst places in Tokyo Ghoul to live, let alone for an orphan. Children shouldn’t be left unattended in general…

While Touka’s reaction here (”Kill all the doves”) is an overreaction, it’s an overreaction to Kuzen’s overreaction. And yes, this is an overreaction. What logical reason is there for Kuzen to throw Hinami in the 24th Ward? I think it’s safe to assume it relates to the CCG confrontations that he gives moments later to Touka’s idea of killing all of the CCG.

TG 16

That still doesn’t make sense, though. Because even if he’s not on the radar because of his connections with V, Kaya, Koma, and Yomo are. A ghoul’s face being exposed is a big deal, yes, but the investigators had no knowledge of what Hinami actually looked like, and a simple investigation of his own could have solved that.

TG 20

To clarify this description is so vague as to be meaningless. It’s basically saying “this vaguely child sized person with a clover dress and a coat”. Hinami literally has to change her clothes and survive a few months and she’ll no longer fit this description in any way. In the end, there is a middle ground between these two sides - Hinami stays with a member of Anteiku and they protect her, and that’s exactly what happens anyway.

TG 31

Oh and also Hinami gets a haircut, grows because she’s still growing, and changes her clothes. Because she’s alive. The thing is, this is such an obvious and simple answer to the problem at hand that it should have been Kuzen’s first reaction. Touka’s not realizing this immediately is logical. Touka herself has a history of losing people to the actions of the CCG - her own parents directly, and indirectly Ayato. Touka being blinded by her rage is understandable.

Kuzen, meanwhile, has no excuse. He’s many times her age. He’s coolheaded enough to realize not to attack the CCG, and he’s old enough that he should have experience to realize the flaws in his logic. Again, like with his decision to “help” Eto, this is not a split second decision.

TG 17

As a result of him not doing so, the very thing he was trying to avoid, Doves dying, ends up happening anyway. And the very result he was trying to avoid, vengeful Doves, follows. This is a pattern with Kuzen’s actions. His actions keep leading to results he doesn’t want, because his actions have no logical basis of succeeding at anything he claims he wants them to.

TG 25

Kaneki, Touka, and Hinami subsequently are all almost killed. Kuzen and Yomo eventually show up, but they were mainly preoccupied with Kaneki and in the case of Touka it wasn’t even a last second save Hinami did. Kureo Mado’s quinque was in the midst of being swung meters away aimed at Touka’s head when Hinami cut it off.

All because Kuzen lacked the foresight to think that abandoning an innocent 14 year old in a hellhole was a bad idea. And he really should know better. Kuzen left Eto in the 24th Ward after Noroi died and he got… obvious results.

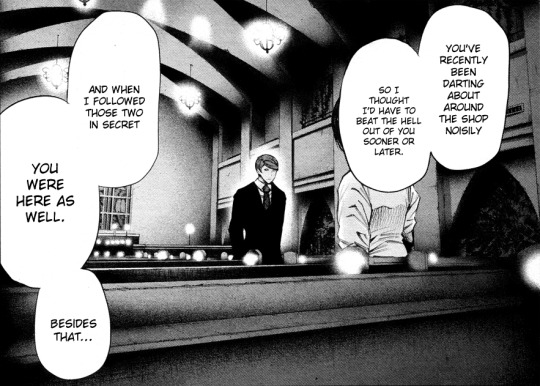

TG 32

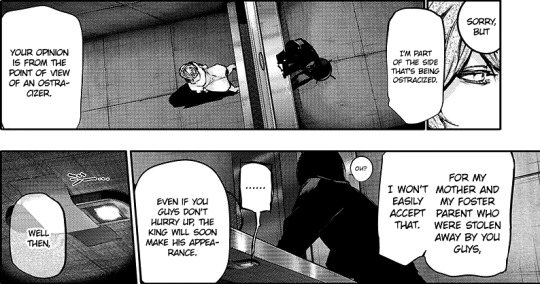

Lets move on to Kaneki’s encounter with Tsukiyama. We’ll start this by making an observation of Touka warning Kaneki about Tsukiyama. This might seem insignificant, but it’s not. Touka’s warning almost worked, were it not for Tsukiyama’s cunning and Itori’s goading, Kaneki would have likely avoided the Gourmet Arc. It’s rather interesting comparing this to both Itori and Tatara’s commentary on Kuzen, where they both make a good points about Kuzen’s treatment of Kaneki.

TG 34, TG 54

There was literally no good reason for Kuzen to not warn Kaneki of the impending danger around him. We know Kuzen’s reasoning here, according to Yomo, it’s to keep Kaneki from getting caught up in the confusion. The problem is that’s already too late. Kuzen already knows Kaneki’s mixed up in V’s business, the CCG’s business, and the Clown’s business, whether he likes it or not. He knows, and decides not to tell Kaneki.

To get back to Tsukiyama, Kuzen’s reaction shows, once again, a lack of learning anything.

TG 40

This is one of the many times that Yomo starts to questions Kuzen’s decision, but doesn’t fully follow through with the thought process. And it’s hard to do so, which I’ll get into later, because Kuzen has many redeeming qualities. But that doesn’t change his downsides. Remember, his inaction almost resulted in three of his people getting killed, and resulted in two members of the CCG getting killed.

Tsukiyama himself literally almost just had Kaneki tortured to death and eaten alive by a group of hungry ghouls. They just finished having a conversation with Kaneki about this very issue. Yomo is clearly worried about Kaneki, and he has a very good understanding of his strength because he’s been training him. This is not stuff that has not already come to pass - this is stuff that has passed.

TG 40

Que Touka, almost as if it’s a joke and she was listening in on them. As if her expression directed at the discussion and Kuzen’s poor decision making, and not Loser. As if it’s meta commentary.

TG 42

Touka picks the opposite decision that Kuzen does, and is in the right. Had she not shown up, Tsukiyama would have likely eaten Kaneki and Kimi, and killed Nishki. You can’t really be hands off when the guy in question is trying to kill one of your people, you know? But Kuzen doesn’t see it that way.

TG 18

You could say that, in a sense, Touka is paying Kaneki back for his own disregarding of Kuzen’s direct orders saving her in the process. One of the patterns that goes hand in hand with Kuzen constantly getting the worse outcomes is of course, characters going against Kuzen’s will and getting improved outcomes.

TG 59

Kaneki’s rescue from Aogiri is actually an example of Kuzen doing the right thing. Still interesting to note that Touka immediately knows she’s going to save Kaneki and makes it known, which contrasts with Kuzen’s malingering on the issue.

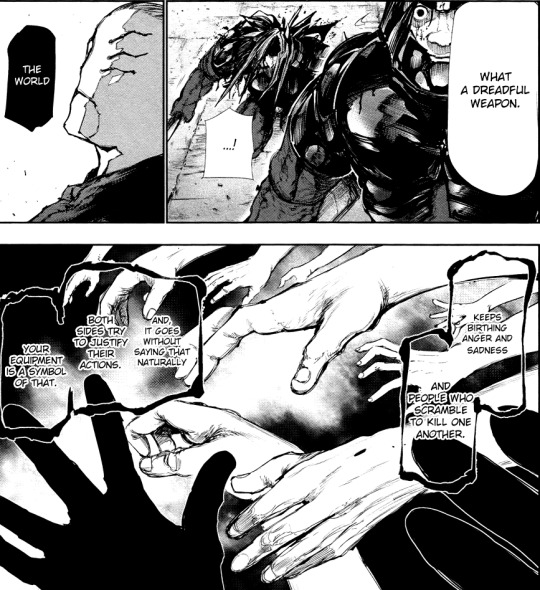

TG 124

Kuzen’s stand at Anteiku was also just pointless. He frames it as a stand against V for Eto when Kaiko chats with him, but how does fighting at Anteiku do so? How does this protect or help Eto? How does fruitlessly dying against the CCG stop V from going after Eto? Again, it doesn’t.

Even if Kuzen was going to be chased by V, we know you can avoid them for years with occasional fighting (see: Shachi, Noroi and Eto, Rize pre-Binging). And if you actually want to fight them, there are better means than playing defensive against a bunch of CCG agents protecting literally nothing.

TG;re 140, 65

It’s not like this is like Rushima and Coachlea, where the goal is to split the forces of the CCG to enable a rescue operation. The diversion Aogiri Tree made was an absolute necessity for the success of the Coachlea raid. And it’s not like there are countless numbers of noncombatants who couldn’t defend themselves if Kuzen didn’t fight, like in the 24th Ward. The stand made there was a necessity to stop the slaughter of civilians.

Kuzen didn’t have to fight, and neither did the Dobermans or the Apes. A lot of people just ended up dying for no reason. Anteiku was just a place that could have been rebuilt, which is exactly what the rest of the Anteiku crew sans Kuzen and Kaneki did. It was literally a building, the people inside the building are what mattered. And Kuzen decided they had to die and then effectively blamed it all on Eto. Because regardless of whether or not that’s what he intended, that is what he did.

TG 128

Kaneki is clearly implying that this entire battle, this entire fight is entirely Eto’s fault here, he’s just not saying her name. We’ll get back to this later on, because it’s important, and it explains a lot of the Anteiku/Eto interactions.

TG 130

Now the Anteiku raid itself. Kuzen framed the entire thing as a fight for Eto. He brings Kaya and Koma along with him, but as noted above, this doesn’t actually help Eto in any way. As noted above, if Kuzen just ran away, hid himself, anything, really, there would be no consequences to anybody.

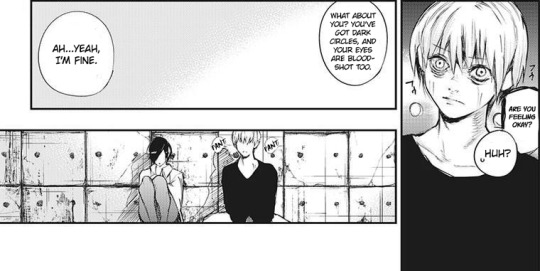

Touka attempting to rush to Anteiku was a foolish move, and it makes sense that Yomo stopped her. The problem is Yomo’s response to Touka’s response. Touka’s the only person in this situation who’s actually shown putting any thought into the situation, and yet she’s being belittled for it.

TG 130

Kaneki, Kaya, Koma, and Kuzen are all on suicide missions for no good reason, hoping that things will work out. Touka is desperately trying to understand, but can’t, because there is no logical reason for this to happen. People are just dying over a literal building. Touka’s objection destroys Kuzen’s argument here about redemption through death and how arbitrary he makes it. Yomo really has no good responses to Touka’s objections here, he just deflected with saying she’s too young to understand the thing that he himself doesn’t understand. He even outright agrees with her.

TG 130

He tries to play off her being confused by a senseless action leading to countless deaths as her “throwing a temper tantrum”. He adopts Kuzen’s policy of inaction once again, even though he feels this is all wrong. He even acknowledges this years later.

TG;re 171

The problem is that he still doesn’t see the pointlessness of Anteiku, here. No one does. Even Nishki and Kaneki were trying to rationalize the battle as Kuzen trying to cause enough chaos that the Anteiku crew would not be found.

“Or how it could have ended without losing Anteiku…”

We are literally shown how to have ended the situation without losing Anteiku, outside of a name change. It’s literally a situation that Yomo himself was in just months before in universe. It’s just that Yomo can’t bring himself to acknowledge the reality of Kuzen’s actions. He somewhat seems to have started to understand it towards the end of ;re, but not quite. On some level, he’s still trying to justify the battle. “Maybe if I had fought in that battle” is just that. The right answer would have been to… not fight.

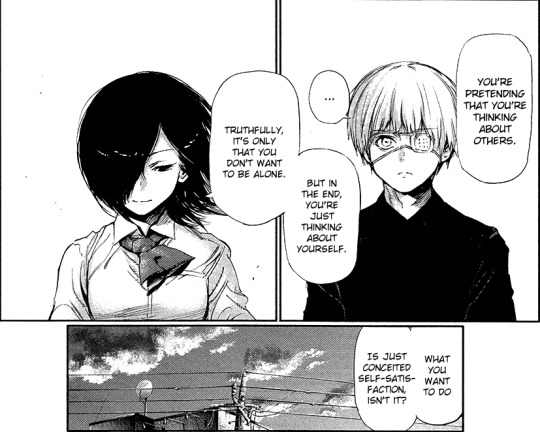

So, what was Kuzen’s real reason for the battle of Anteiku?

TG 120

I think the answer is the same as it is for many characters in this series. We hear it from Touka, who rather purposefully shares many parallels with both Kuzen and Eto, talking to Kaneki, in an arc that is a parallel to Kuzen’s own. Saying this to Kaneki in the chapter right after Kuzen tells his story to Kaneki, and right before the destruction of Anteiku.

Kuzen didn’t establish Anteiku solely for Eto’s sake. He did it so he could say to himself he founded Anteiku for Eto’s sake. Kuzen didn’t fight the CCG for Eto’s sake. He fought the CCG so he could say he fought for Eto’s sake. He did it for the self satisfaction, a way to soothe the guilt.

Because Kuzen , just like Kaneki, hated being alone. And so he starts doing anything he can to stop from being alone, while paradoxically wanting to die while living as long as he can, like Kaneki did. Anteiku is a parallel to Kaneki’s story as a whole.

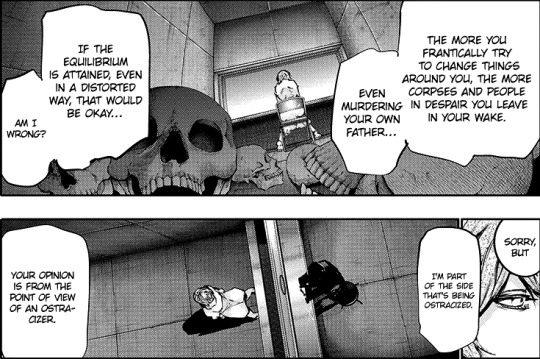

TG 126

Just as there’s a reason Eto was hunted down and forced to work for Arima (and yes, she’s forced to; the moment Arima discovered her identity, she has no choices left) despite Kuzen’s “protection”, there’s a reason that Anteiku was destroyed despite Kaneki’s “protection”. Because destroying Aogiri doesn’t solve the underlying issues that cause threats to Anteiku to begin with.

It doesn’t break the bird cage caused by V, it doesn’t solve the issues between humans and ghouls, it doesn’t even remotely encourage that. Destroying Aogiri doesn’t even solve the immediate threats to Anteiku in Tokyo Ghoul - V, and groups that work with them, like, say, the CCG. The groups who actually targeted Anteiku and actually destroyed it, and not just a theoretical that Kaneki proposed in his head.

TG 63

Because Aogiri never intended to attack Anteiku, a few individual members did of their own accord. Think about it this way: If they were intending to destroy Anteiku and kill all of its members, why would Ayato be in Aogiri when his goal is to protect Touka? There’s nothing that actually indicated that Aogiri had any interest in Anteiku outside of just checking out Kaneki’s worthiness as a possible One Eyed King.

Tatara, Eto, and Arima never even intended for Kaneki to be tortured in the first place.

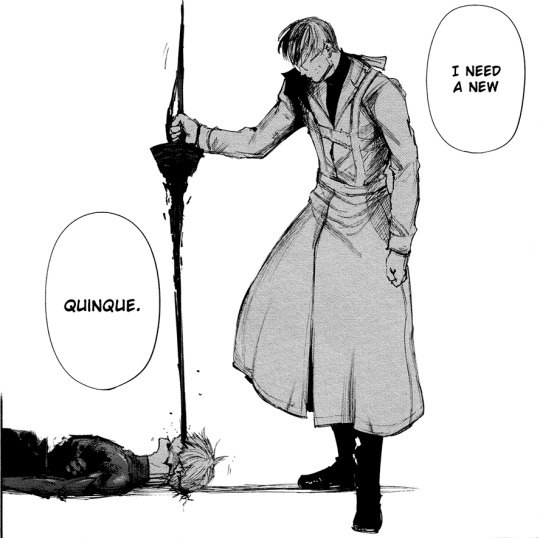

TG 54, TG 75

Tatara actively writes off Kaneki and gives him to Ayato, not Yamori. Ayato, as in the guy who angers Yamori, and who Yamori didn’t want to cross. The reason Kaneki was tortured was’t because of Aogiri using Yamori as a roundabout means to do so (why would they bother doing so in such a manner?), it was because of, primarily, Nico’s extensive machinations enabling Yamori to do so.

TG 58

Kaneki projected Yamori, a guy who has less in common with the average grunt of Aogiri as Kijima does the random grunt of the CCG, onto the rest of Aogiri Tree. Yamori was legitimately hated by the Aogiri members as a whole, this is made explicit on multiple occasions. Yamori also rather explicitly has literally no loyalty to Aogiri Tree. His motive? “it’ll be fun”.

Yamori torturing Kaneki was explicitly treason here, in the sense that he had to commit treason to do so. The only reason that the Bin Brothers didn’t try to fight Yamori was Nico and the oncoming CCG battle. We’ll leave this at that for now. However, it’s made clear that Nico was the one who enabled Yamori to torture Kaneki by stopping Kaneki’s and the others’ escape at every turn and being the one who lead Yamori to him in the first place.

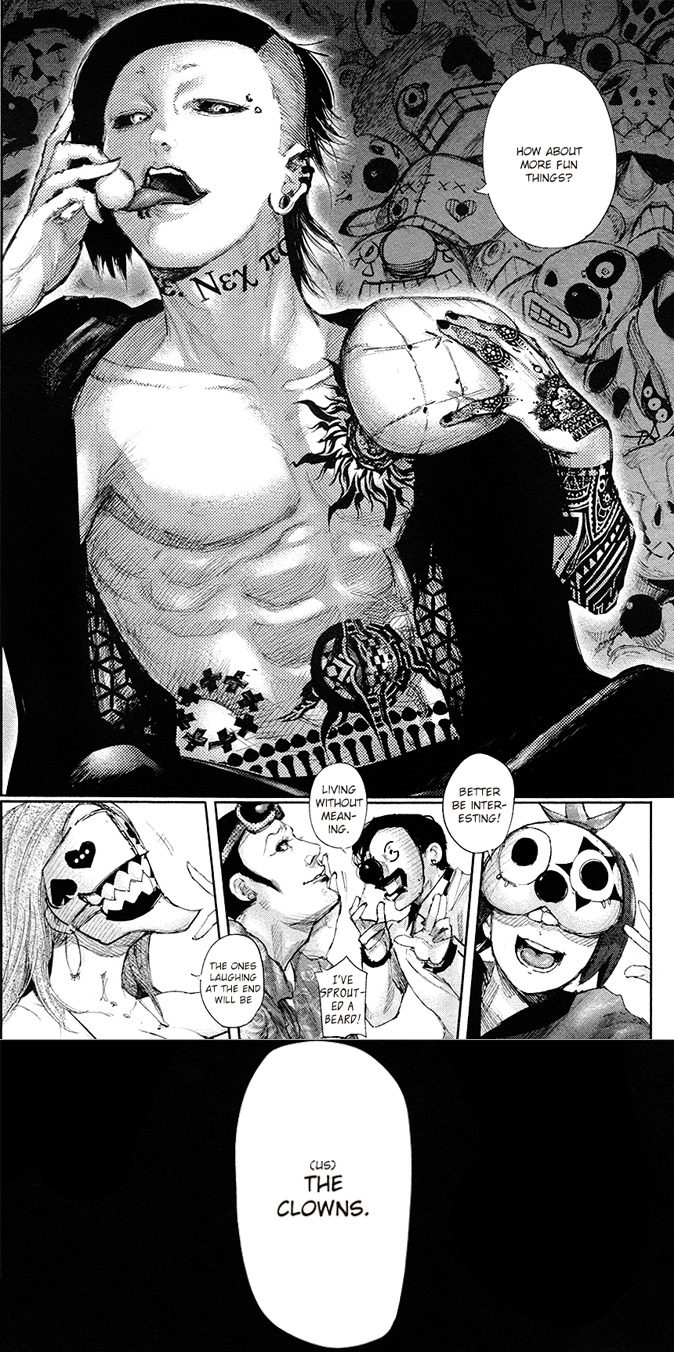

TG 139

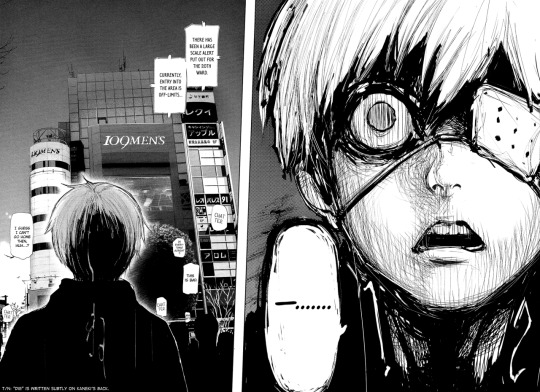

The tragedy of the original Tokyo Ghoul wasn’t that Kaneki’s actions amounted to nothing because the CCG’s attack made Kaneki’s actions against Aogiri meaningless, and he decided to shoulder the burden of fighting everyone alone. The tragedy of the original Tokyo Ghoul was that Kaneki didn’t actually protect Anteiku, because his actions had nothing to do with protecting Anteiku. In the end, Kaneki ends up in an unwitting battle against the One Eyed King and is defeated before he can reach his goal of Anteiku. He fought a series of pointless battles against Aogiri, because a Clown set him up.

TG 78

That’s why Nico’s saying all this to Furuta in a chapter called “Diversion”. It’s… literally right there. Eto and Aogiri a diversion for Kaneki from his true goal: being loved and finding happiness. Nico even kind of just outright says they had Kaneki tortured because they wanted to see the changes a human goes through when they enter despair. There is a very, very good reason why Kaneki is always portrayed as being at his worst when he’s going after Eto in both Tokyo Ghoul and Tokyo Ghoul ;re.

They’re mentioning Eto indirectly here, and how she’s not the One Eyed King (Nico lied to Kaneki - not Furuta) to foreshadow quite a bit. The tragedy of the original Tokyo Ghoul was that Kaneki’s actions were meaningless the entire time, that he wasn’t actually fighting the real threats to his loved ones, and he learned the wrong lessons from his experiences.

TG 143

That was the point of this entire scene with the Clowns celebrating at the end of Tokyo Ghoul. Like, they’re even referencing Yamori’s line here. Kaneki went on some random warpath against someone who is mostly irrelevant to his happiness and could have even been an ally to him (like Tsukiyama, or Nishki), who eventually became an ally to him in ;re, but not the actual threats to Antieku. Kuzen is the same as Kaneki. That’s how they parallel. The only difference between Kaneki and Kuzen is that Kaneki was tricked and misled, whereas Kuzen wasn’t.

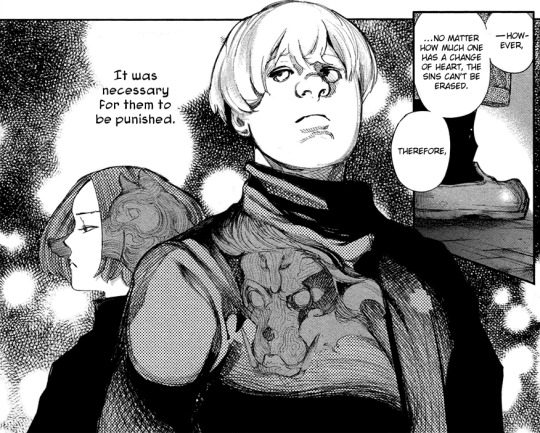

TG;re 71

Kuzen is completely aware of this fact. He knows his actions aren’t actually helping Eto. That’s the subtext here, even if Yomo doesn’t pick up on it. Yoshimura even lampshading that, more often than not, he gets the opposite outcome than what he wants in his statements here.

TG;re 62

I believe this scene to be grossly misinterprreted. The question I usually see pop up here is “Why is Eto getting so unreasonable here, so ungrateful towards her father?” There seems to be this perception that Eto could just walk in through the front door, that Kuzen would just welcome her with open arms. But there’s nothing to suggest that he would.

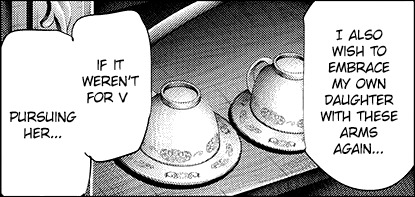

TG;remake 1, TG;re 62

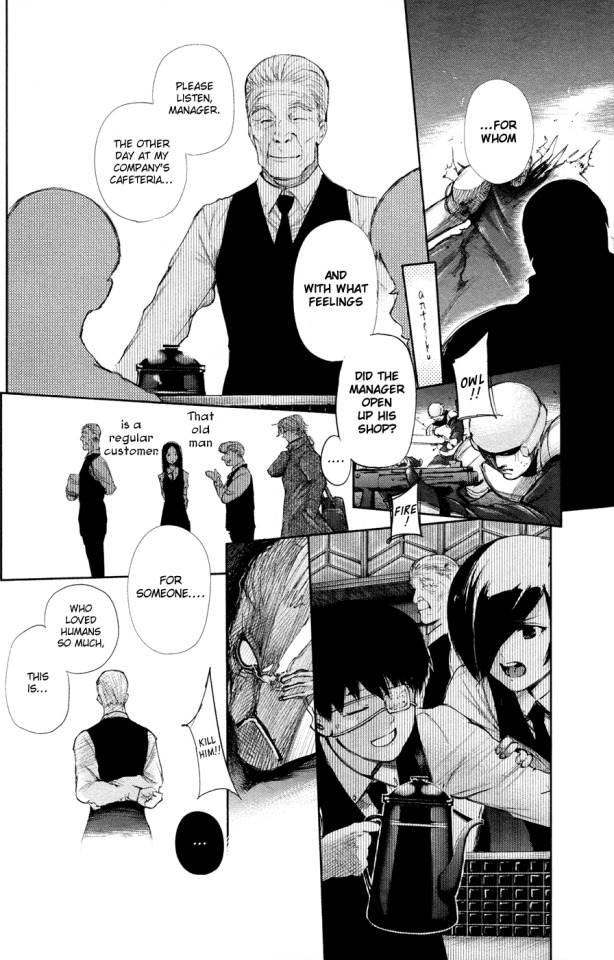

This novel Eto drops in front of Anteiku is about the longing for parents, or in other words, a family, while living in a hellish situation. Just look how long he lingers on the novel she drops in front of his door. This indicates the novel itself has meaning to him.

TG;re 63, TG 124, TG 119

Consider that Eto looks just like Ukina. Now consider that Eto makes public appearances and has her novels known around the world. Kuzen even imagines Eto in his mind’s eye during his speech to Kaneki. The implication here is that Kuzen is just as aware of Eto as she is of him. The other implication here is that Kuzen’s lingering on Eto’s novel because he knows she just walked by and dropped the novel as a message to him.

The real question should be “How does Eto know who Kuzen is?”

TG;re 71

The implication here is that Kuzen came forward to Eto. Given his foiling with Touka, and his intentions with Hinami, all point towards one thing: Kuzen’s last embrace of Eto? Wasn’t from when she was a baby. It was probably shortly after she published her novel. That is how he knows V is still pursuing her. That is why she is so angry. That is how Eto knows who he is. That is why Kuzen lingered on Eto’s novel for so long. Kuzen did with Eto the exact same thing he wanted to do with Hinami. Only with Eto, there was no one to tell him “this is wrong”.

Eto started working as a novelist as a 14 year old. Eto was forced to become a child soldier as a 14 year old, fighting a war against V, who controls the entire world, as a 14 year old. Not for her own selfish ends, not for simple revenge, but for the plight of her fellow ghouls.

TG;re 65

And Kuzen’s not helping her, he’s not taking care of her, he’s not taking notice of her, he’s not actually doing anything for her. The opposite of love is not hatred - the opposite of love is indifference. And Kuzen comes off as being completely and utterly indifferent towards Eto’s struggles. Eto’s writing novels about living through hell, because she’s being hunted by V, other ghouls, the CCG, and the only support system she believes she has at that moment is maybe Arima.

TG;re 62

So when Eto walks by Kuzen having a happy fun time with his new family, while she’s suffering alone, when she’s being hunted by V, she gets upset. And it’s completely understandable. She’s struggling alone.

(this image is from TG 125 and TG;re 71)

Kuzen wished for Eto’s embrace, to have a cup of coffee with her. He created Anteiku as a home for her, the name being an anagram of her name and her mother’s name; but in the end, it never amounted to any more than a wish. V was never going to go away without someone to stop them, and Kuzen had already resigned himself to never be able to do anything to beat them.

Therefore, Eto could never come to Anteiku. Kuzen referred to Eto using such terms with fantastical connotations, but simultaneous common usage, such as “wish” and “miracle”. Perhaps that was by design? Because he knew the arbitrary requirements he designed to be met could never be. These words would have immediate meaning to those around him as merely expressing desire; but in reality, they’re acknowleding it’s pure fantasy.

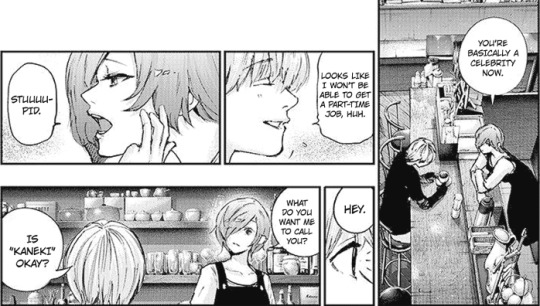

We’ll contrast Touka’s inaction with Kuzen’s inaction, because they’re two very different things. Both Kuzen and Touka made homes for Eto and Kaneki respectively to return too, and both avoided grabbing them and bringing them to those homes. But the reasoning here is polar opposite.

TG;re 42

Touka doesn’t want to bring Kaneki to this home she made for him because by being part of the CCG, he’s protected. The investigators know his identity, and will search him out if he runs away. Being in CCG custody and under their protection? It’s the safest thing for him. Of course, if he does run, he will always have a home at ;re. Touka is actually ignoring her own wishes, her wish for Kaneki’s return, because she thinks this sacrifice is necessary to keep Kaneki safe - because she believes he’s safer without her.

The other part of this equation is, of course, Haise Sasaki and the members of the CCG. Haise Sasaki is just as much a part of Ken Kaneki as any other “personality”. Haise is not something that can simply be removed from Kaneki.

TG;re 121