#feudal France

Text

How hard can it really be to build the perfect castle? Here are some of the biggest innovations in castle building anyone interested in finding out needs to know.

#castle#motte-and-bailey#Normans#towers#moats#gatehouse#medieval history#middle ages#feudal France#ancient#history#ancient origins

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Seignobos, Charles, 1854-1942, and Earle Wilbur Dow. The Feudal Régime.New York: H. Holt and company, 19041902.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Knowing that Napoléon is on the record as having said

I had been nourished by liberty, but I thrust it aside when it obstructed my path.

(as well as tampered Almost Always with votes and democratic elections) not only makes it perfectly clear why

"What could be greater?"

"To be free."

is such a one-hit KO but also 1000% apparent how hard that response fucks.

#which also feels a little like the system Javert has bought into interestingly enough?#but yeah it's really neat because Napoléon developed this merit-based system and took away feudal privileges#and did a lot to improve public infrastructure and develop accessible public education throughout France#and helped with religious freedom#but this one value ... he just couldn't find room for it and didn't see how it could fit into a functioning world#and it's one of the most important values of the amis#and frankly one of the most closely-held by Romantics imo#freedom beauty love#les mis#combeferre#ferre#être libre#to be free#combeferre has never done anything wrong in his life#napoléon#les amis#shitposting @ me

132 notes

·

View notes

Text

i spent all fucking dayyyy on this paper. 8 pages. of me talking about fucking nothing. not in the “this is all filler bullshit” way, in the “literally no one but an English major would find any enjoyment in reading/writing this” way

#it’s abt Marie de France’s Lais specifically the poem ‘Lanval’. and about how the defiance of gender roles critiques the larger feudal#system. and like. a lot of postulating on morality and masculinity. SNORES. ILL ADMIT IT. HONK SHOO. but I enjoyed it#lee speaks

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Normandy and Champagne, a paradox

One of the paradoxes of French history is that the duchy of Normandy, subject to the monarchy since the early thirteenth century, emerged from the Middle Ages with stronger provincial institutions than the county of Champagne, which was not definitively attached to the crown until 1361. By the early sixteenth century, the old Norman Exchequer had grown into the Parlement of Rouen, while in Champagne the Jours de Troyes withered away and the county remained under the jurisdiction of the Parlement of Paris. Although Rouen and Troyes are about the same distance from Paris, the Norman city became a provincial capital, while Troyes was subject to the influence and administration of the central government and Champagne became a province without a capital.

The reign of Philip the Fair was a turning point in the development of the two provinces, and the explanation of the greater dependency of Champagne contains an ironic element. When Philip Augustus conquered Normandy, its administrative and judicial institutions were independent of the monarchy and there was a clear demarcation between the rights and obligations which were Norman and those who were French. Since the king replaced his predecessor by conquest, the simplest way for him to govern his new territory was to keep the institutions separate but to replace the administration with men loyal to his court. The feudal history of Champagne before its acquisition was quite different, for its counts never had the independent power of the Norman dukes, and the western frontier of the county was permeable to royal influence. People from Meaux, for example, could go more easily to nearby Paris than to Troyes, and since the king exercised considerable feudal authority in the county, many religious houses and some lay vassals found it advantageous to invoke the king's power against the count. Even before Philip the Fair became count there were plenty of excuses for royal administrators to act in Champagne, while there was no reason for a royal agent outside Normandy to interfere with another agent of the king inside the duchy.

When Philip became both king and count, there was no longer an independent administration with an interest in opposing royal influence. There was also pressure within Champagne to take cases to the more powerful court, and litigants on expense accounts (like the communal office of Provins) undoubtedly preferred to plead in Paris rather than in the moribund city of Troyes. The flow of cases from Champagne to the Parlement could only have been checked if the government of Philip IV had made an effort to prohibit it, as Philip III had earlier attempted to limit the cases coming to Paris from provinces which had royal baillis. But Philip the Fair, count only in his wife's name, had no reason to build a strong local judicial system in Champagne. The masters of the Hours were not recruited from the county but sent from the royal court, and cases could be judged in Troyes or Paris as convenience dictated. Finally, when it was apparent that the monarchy might not be able to appoint the masters of the Jours indefinitely, Philip established the right of appeal from the Jours to the Parlement, a principle it was not necessary to impose on Normandy. The great centralizer of medieval France subordinated the Jours but permitted the Exchequer to remain relatively independent because in his day the monarchy had a firmer hold on Normandy than on Champagne.

John F. Benton & others- Culture, Power and Personality in Medieval France

#xiii#xiv#john f.benton#culture power and personality in medieval france#history of normandy#history of champagne#feudality#philippe ii#philippe iv

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

#my first post here shall be shameless self promotion#tier list#flags#coat of arms#escutcheon#emblems#nations#france#nobility#feudalism#medieval#habsburg#de valois#youtuber#Youtube

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

This Day in Anarchist History: The Paris Commune

youtube

0 notes

Text

Upon the edge of destiny, A choice must be made, with weighty consequence. In realms of past, and cultures forgotten, The echoes of time whisper in secret. In ancient Egypt's golden age, Two hearts entwined by Fate's design, To build a pyramid for the gods, Or sail the Nile to find their fortunes. In feudal Japan, where samurai's word is law, A daimyo must decide: Conquer land or spread peace? A life of war or harmony? The ripple of his choice echoes still. Upon a moonlit night in 18th century France, A queen must choose between love and duty: To marry for alliance or follow her heart's desire? The kingdom's future hangs in the balance, as hearts break and fates collide.

0 notes

Text

nationalism makes no sense, but these other things do

the very concept of nationalism is retarded. why should I be loyal to some abstract concept like “america” or “france”? it’s just a name and corresponding borders.

loyalty to people, ideology, religion, and family makes sense to me, but the more I think about nationalism the more insane it sounds.

what does it mean to be nationalistic? to be loyal to the concept of a nation? are you loyal to the government? the people it rules over? the system of laws which govern you? none of these makes sense. if nationalism was loyalty to the government, than the moment that the regime changes (as it does every 4 to 8 years in the United States) the corresponding nationalism should evaporate. if nationalism involved loyalty to the people, and the majority of the people disagreed with your views, then logically you should change your views to match the majority. if nationalism means loyalty to the system of laws associated with the government, then any time a law is added, removed, or changed you would logically have to abandon your earlier opinions to embrace the new ones. none of it makes any damned sense.

conversely, loyalty to people is natural. if you like someone, and see them as worth protecting, serving, or listening to, then it is only natural for you to act on those impulses and solidify that bond. with families this bond of loyalty is ready-made from shared experience and dependency. with friends, this relationship forms naturally and unconsciously from a sense of comradery. A knight swearing fealty to his liege does so out of respect for his liege, or at least appreciation for the land and resources his liege personally grants him. A couple who gets married solidifies their relationship spiritually, physically, and legally. all of these are natural relationships that emerge from the basic instincts of humanity.

Loyalty to religion or ideology is in a certain sense even more fundamental, as it involves the subject’s world-view. while things like “communism” or “catholicism” are abstract concepts like nationalism, they involve concrete shifts in the way the subject sees the world. the communist will, for example, begin to see the world through the lens of class struggle and naturally seek to aid those he identifies with (looking out for the interests of the working class), while a catholic will desire to act upon the will of God to do good deeds according to the teachings of the Church (such as donating to poverty relief and medical research). such individuals, in either case, are not acting out of loyalty to the regime, but instead out of a desire to act in accordance with his world-view. a member of the Vegan ideology believes that consuming animal products is inherently immoral, and therefore will not only refrain from eating them, but naturally seek to convince others not to eat them as well. the vegan is not acting out of loyalty to Veganism, but rather out of a desire to do good and prevent evil through the lens of his worldview. in this way, loyalty to ideology or religion is actually a form of loyalty to oneself, specifically the dictates of one’s superego.

these make sense to me. nationalism does not.

#nationalism#religion#ideology#family#loyalty#feudal#medieval#monarchy#catholic#catholicism#communism#veganism#united states#america#france#class struggle#good#evil

1 note

·

View note

Text

which civilization had the greatest metallurgical skill/knowledge?

which civilization had the best metallurgy?

which civilization had the best geological potential for metallurgical prowess?

#part of a series of questions i have for trying to solve 'why industrial capitalism in the west when it did'#i THINK the answer is some combination of capacity for metallurgy; some pathway for electricity generation (most obvious ways seem#the way it did; steam engines for getting water out of coal mine (b/c this takes care of the wagon equation)#or with hydropower tho i'm less confident on that--that might require too much high precision machinery)#some way to use those two to get to high precision machining; and then you might also need a HUGE capital dump in order to get political#liberalization (because you need some way to get out of Holy Roman Empire levels of friction -- I think this might have been some of the#issues that China + Italy had with getting industrialization quickly)#england is fucking weird; it had political liberalism BEFORE it became a naval power iirc#france makes sense because Louis XIV was a steamroller that cleared out most of the old growth and the Revolution took care of the rest#i'm pretty happy laying the blame for the Revolution as a combination of ineffectual poltiical forces and climate but i haven't checked#HRE had to wait for napoleon to bulldoze the feudal power structures; in Italy I think it took unification;#Russia has similar known causes#I think Spain/Portugal had a case of getting too rich too quickly? not sure.#that mostly takes care of europe; 'why didn't the nords do industrial capitalism' is still an open question to me#same thing with the ottomans#elsewhere in the world I don't know enough about

0 notes

Text

something thats annoying about pseudomedieval fantasy worlds is that they often depict a 17th-century-france level of absolutist monarchical power alongside what is otherwise a 14th-13th century society. if you're going to set your novel in a feudal setting and have the audacity to tell me to give a shit about rich people at least put in some convoluted power struggles between different layers of imperial bureaucrats, landed aristocracy, and local smallholders goddamnit

873 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aristocracy of Men of Arms

Seignobos, Charles, 1854-1942, and Earle Wilbur Dow. The Feudal Régime.New York: H. Holt and company, 19041902.

#Hathitrust#feudalism#nobles#warriors#chevalier#france#caballero#spain#ritter#germany#europe#charlemagne#emperor

1 note

·

View note

Text

The House of Capet.

987-1328

The Capetian dinasty was the first French dinasty resulting after the death of Louis V (c.967-987) last Frankish king of the Carolingian Empire. In my HC, this Frankish personification is father of both France and HRE, and also Austria. After the colapse of the Carolingian empire, the Kingdom of Francia disappeared and the empire was partitioned in three big territories; West Francia (France), East Francia (HRE) and Middle Francia (the territories that the both of them will be fighting for in the centuries to come, the Benelux spawned from those territorial wars in between them, as well and Switzerland and everything in between).

France and the Holy Roman Empire would become natural enemies, then, as Franco's inheritance would be the same as that of the Carolingian Empire; to become the next Roman Empire. And both kingdoms would spend the rest of the centuries until the World Wars trying to achieve that inherited goal. It has a name, in fact; Franco-German enmity.

Hence, then, the name Holy Roman Empire, from the intentions to become the next great empire uniting the three continents. France is the older son, by the way. The Frank had... a little favoritism towards the youngest, because it was identical to him. And more visibly German, of course. This fueled the competition between the two and the hereditary and historic animosity between the two "princes".

It was the Franks that started the monarchical rule, feudalism and the hereditary rule for the sons in Europe. So France, HRE and Austria would be the first princes, haha.

#hetalia#aph fanart#aph france#francis bonnefoy#hws france#historical hetalia#myart#As always this are my HCs based on historical events#no one has to agree with them or anything

217 notes

·

View notes

Text

Quick worldbuilding hack, if you want to make a coherent political system for your fantasy world:

Basically, between the fall of Rome and early modern times, in Europe* most political organization wasn't actually kingdoms ruled by One True King like it's usual in fantasy, but something like this:

Feudalism: here, the center of power was not the nation (there was little concept of such thing) or the state, and not even the King, but the landowners (from kings to dukes to counts...) and their network of vassalages to each other. There were no "countries" but rather hereditary titles, and the people who held them. There was little of a true state besides what individual rulers did; they didn't even have formal armies as such, but rather the vassals who provided them, they and could have multiple allegiances. Examples are of course the Holy Roman Empire (neither holy, etc. etc.) France (note that the 100 Years War was a dispute about titles rather than France vs. England), Spain (actually a bunch of kingdoms and crowns rather than a country), etc...

"Empires": A state where a central goverment exerts power over other territories and peoples. These are rather familiar to us, because a formal state exists here, and the ruler is more powerful and often does have a standing arming and administration instead of relying on vassals. Here, there is a bureacracy and a claim to rule a territory, and while they might have vassals and prominent artistocratic families (everyone did) their administration was state-based, not allegiance based. The Roman Empire is the most imperial empire, as well as its cringefail successor the Byzantine Empire, but note that the great Islamic empires also had this kind of administration, with governors appointed and confirmed by the imperial court.

City-States: Basically a powerful city (though they were often the size of small towns, still, very rich) ruled by a local aristocracy, sometimes hereditary, sometimes elected from a few families or guilds, or a mix of both, and in some cases ruled by religious authorities. These could be independent or organized in alliances, but were often vassals of more powerful goverments such as above. Cities are in many way the building brick of larger states; of note, in the Ancient Mediterranean before Rome conquered it all, leagues of city-states were the main powers. Medieval and Early Modern independent city states were the Italian city states of course, and a famous league was the Hansa (many of its members themselves vassals of other powers)

Tribes and Clans: Every culture is different with this, but basically here the centre of power is the relationships between families and kinship. If this sounds familiar to Feudalism, you've been paying attention; Feudalism is what happened when the Roman empire and administration fell, and it was replaced by landowners and their ties of vassalage and allegiances.

Now, besides the history lesson, why is this important? Because there are reasons why rulers had their power, and you should know that.

A king never ruled alone. He was only the head of nobles tied by vassallage (feudalism), or the head of a inherited state bureaucracy and army ("empire"). If you killed the king, another one would rise from the prominent families. Often by bloody civil wars or conquest yes, but the system overall would stay. A king did not reign by its own power or virtue, but because the system itself supported him, and of course, he maintained the system.

A new king who wants to replace the bad old king (a common fantasy storyline) needs to also deal with the allegiances of all its vassals (who would probably rather kill him and take the throne themselves) or build a bureaucracy and an army, supremely expensive endeavors in those times, which took decades if not centuries to build. In fact, the Byzantines and the Arabs inherited most of their state aparatus, in one way or the other, from the Romans.

This is also why these systems lasted so long, too. The appearance of modern republics and other systems of goverment needed the coordination of people and revolutions that did not just kill the king, but also replace it with something else, and for that you need literacy, economic changes, an empowered populace... But that's for another time.

I hope this is fucking helpful because I don't want to spell allegiance ever again.

*I would love to do more about goverments outside Europe, especially Precolombine American ones like the redistrubitionist state-based economy of the Incas, or the Mesoamerican city-states. But that's for another time.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

"The French Revolution, therefore, assumes a unique place in the history of the contemporary world. As the classic bourgeois revolution, abolishing feudalism and the seigneurial system, it forms the point of departure for capitalist society and liberal democracy in the history of France. As a revolution of the peasants and the masses, and therefore uncompromisingly antifeudal, it twice transcended its bourgeois limits: first during Year II, an experiment which, though necessarily doomed to fail, long retained its power as a prophetic example; then with the Conspiracy of the Equals, an episode that marks the birth of present-day revolutionary thought and action. These essential characteristics probably explain the vain efforts that have been made to deny the true historical nature and the specific social and national character of the French Revolution, for it is a fertile and dangerous precedent. Hence also the shudder that the French Revolution sent throughout the world, and the continued reverberation that it arouses in men's minds even today. The very memory of it is revolutionary, and stirs us still."

-Albert Soboul, A Short History of the French Revolution, 1789-1799

#saw there was some discussion going on about whether the frev was bourgeois or not#and i just finished reading this book#so i thought it would be topical to post some Professional Marxist Analysis :]#french revolution#frev#conspiracy of equals#albert soboul

96 notes

·

View notes

Note

Sorry if that's already been asked but what do you think about the "King's word is the law" in hotd/dance discourse? I'm not sure where that even came from and for me there is 0 evidence that suggests it's true

Hi anon, excellent question! Sorry it took me so long to reply, this got a bit long! This is actually something that comes up a lot when I teach feudalism to my high school students. I've found that most people in general do not know the difference between feudalism and absolutism, and conceive of all kingship as a form of tyranny. And compared to most modern systems of government, of course feudalism and absolutism are both oppressive and restrictive, so the difference can feel a bit like splitting hairs. Neither system gives the the common people any real voice, but the difference is that feudalism is a system with a relatively weak monarchy that has to, both directly and indirectly, answer to both the church and to his vassals. But Westeros, even under the Targaryens, even with the dragons, is not, strictly peaking, an absolute monarchy but rather a feudal monarchy.

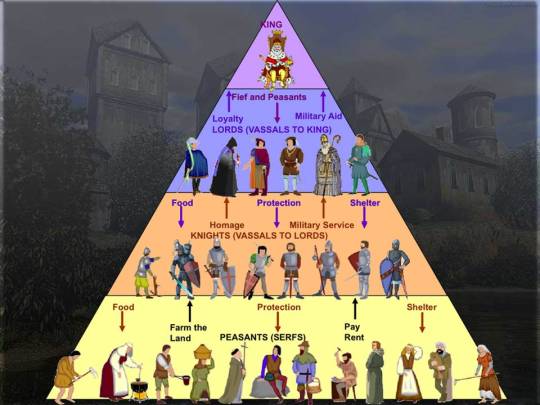

Broadly speaking, in a feudal system "the king's word is law" is only true insofar as the king can enforce that law, and to enforce his laws he needs the support of his vassals, the landholders who supply him with his armies and revenues. The feudal relationship between the king and his vassals looks roughly like this (this is the actual diagram we use in my world history curriculum):

Notice how the relationships are all reciprocal? The king might technically own all the land in the realm, but he has no standing army of his own. Knights pledge their service to the lords, rather than the king (he will have some knights in his personal service too, but not nearly enough to make war). It is in the king's best interest to keep his vassals happy. He needs them! They help him keep other unruly vassals in check, help defend against foreign invasion, and help him wage his own wars of expansion. They also provide the crown with revenue in the form of taxes, and their farmlands are what provide food for the people of the realm. In Westeros in particular, the royal family does not hold much land of its own (the land held by the royal family is called the royal demesne and the Targaryen royal demesne is very small compared to that of irl kings), so it's particularly dependent on the support of the vassalage. This makes it a relatively weak feudal monarchy, all things considered.

(also, notice the bishop up there with the lords? Usually, he would usually be appointed by the king with the approval of the pope, but the question of whether or not church officials were subjects of the king and subject to the king's laws was a huge point of contention hat caused many power struggles in medieval monarchies, and there was a whole separate court system, the ecclesiastical court, to deal with the crimes of court officials)

Anyway, a feudal king who just does whatever he wants without regard for his vassals will quickly find himself being named a tyrant, and the accusation of tyranny is a serious one in a feudal system, because vassals will rebel rather than serve a tyrant. Rebellions were not usually done with the goal of overthrowing the king completely, they were done in order to pressure the king into listening to their demands. We saw this happen with King John, whose barons were unhappy for a number of reasons including what they saw as avaricious economic policies, costly wars with France, increased royal interference in local administration of justice, and conflicts between the king and the church. Eventually, John's barons pressured him into signing the Magna Carta, a document that specifically limited the power of the king and stated outright that the king was not above the law and that the king could not impose new laws without the consent of the lords. John later repudiated this document, which led to further rebellions, and his son and heir Henry III had to reaffirm it after his death (and a series of rebellions still plagued Henry III). Eventually, this leads to a formalization of the idea that the king must not act without the consent of his lords and the creation of parliament.

Now, we never see a Westerosi Magna Carta or the creation of a set parliament, there is the small council and the occasional great council, and lords can and do object to the king's laws, force concessions, and remove kings. Notably, Robert's rebellion in the main series is an example of vassals losing faith in their king and eventually removing him. Aegon V cannot push his reforms through because he lacks the support of the lords, and in his desperation tries to bring back the dragons. But if we look back, even dragonriding Targaryens could not simply impose their will without the cooperation of the realm's lords. Aenys was considered weak and his rule was beset by rebellions, eventually coming to a head when he arranged an incestuous marriage for his heir, this after the Faith was already displeased with his brother's polygamous marriage. This led to Aenys being known as known as King Abomination and the Faith Militant uprising forced him to flee to Dragonstone. Maegor, who followed him, is ousted (and killed) as a tyrant for going further than that, suppressing the faith and committing kinslaying against his nephew. What makes Jaehaerys' rule notable and successful is that he's very good at appeasing the lords and when he is going to do something controversial, like the Doctrine of Exceptionalism or changing the succession, he campaigns and politicks for their support (I maintain that he knew Viserys being picked at the council was a forgone conclusion, but he did not want to unilaterally go against Andal custom without consulting his lords, it's a CYA move). This is something Viserys completely fails to do, not only failing to drum up support for his unconventional choice of heir, but actively alienating potential supporters.

It's worth keeping in mind that "law" means something different in this context than what many of us are used to today. Medieval law, and Westerosi law, was a hodgepodge of custom, statute, and precedent. Westeros, like England, operates on "common law." Successions are disputed all the time because competing claims exist. If Viserys named Mushroom heir, is his word law? What if he names Helaena? Jace? And in a normal situation, if it wasn't the succession of the throne in question the rival claimants would present their petitions, citing evidence and precedent, and the master of law, magistrate, or the king would make a ruling. The will of the lords is especially required to enforce an unconventional royal succession because succession takes place after the king is dead, and so if the succession is disputed, the claimants and the lords of the realm have to settle the dispute, nonviolently if possible, or else civil war will follow.

And you can get the lords behind an unconventional succession, but you have to have a good reason. "She's my favorite child from my favorite wife" is not actually good enough. For instance, when Robb chooses to legitimize Jon and disinherit Sansa in order to keep Winterfell out of Lannister hands, this is widely accepted among his vassals and allies because the reasoning is sound. Jon may be a bastard, but it would be worse for everyone to have Winterfell pass to a Lannister, even if it's shitty for Sansa. By the same logic, initially, Rhaenyra is accepted as heir because the lords do not want Daemon on the throne (the man she is now married to!). But after Aegon is born most assumed he would naturally become his father's heir. And remember, there's no reason for Alicent to marry Viserys if he cannot even ensure he inheritance of his own firstborn son. And Viserys never builds a case for Rhaenyra while he is alive, never tries to present Aegon as unworthy, he never has the lords come reaffirm their oaths, never writes a decree to formalize Westerosi succession. He doesn't take action because he knows he would not achieve anything near consensus (despite certain houses choosing Rhaenyra when it comes to war, it's doubtful they would have made the same choice if it had been a great council), so instead of dealing with the problem, he passes it on to his children.

I think it's fair to view the challenge to Rhaenyra's succession as an objection to what some see as tyranny on the part of the king. Viserys and Rhaenyra set themselves above the law in multiple ways-- not just jumping ahead of a son in the line of succession, but the way she has destabilized her own rule by placing bastards in her line of succession. What they are doing defies all precedent, and in a world where law is built in large part from precedent, this is not something the lords of the realm are obligated to accept.

85 notes

·

View notes