#for those keeping up with the sibling saga: they moved out this weekend

Text

btw no posts today!! my queue ran out and i'll try to set up some more for tomorrow but i'm just chilling rn after that doozy of a weekend

#delete later#for those keeping up with the sibling saga: they moved out this weekend#my parents helped them set shit up bc apparently they had no fuckin idea or plan for the moving out#like. it's fucking scary how they go about shit. how haphazardly they prepared for the move etc etc#AND THEY TOOK SOME OF MY SHIT!!! i want that back and my siblings like. oh parents can drop it off at ur place#bitch???? u think they're carrier pigeons??? i've been getting ur shitty deliveries just come get them urself and bring my hermetic rice ja#absolutely prepared to cut that cord and i would have already were it not for the fucking shit they took.#after that it's game over#and their room was absolutely disgusting. bc they did not clean up after themselves. jackasses.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Gardening/Life Lessons aka Plant Wisdom 🌱 🍃 🍂 The best laid plans, #amiright ? 1️⃣ my (NOT) perfect^ strawberry patch! I intended to expand this year and let the strawberries take over more garden space! 🍓 🙃 Even an intention set is not a goal achieved. Building in a cadence of check-ins to center back on the intention, co-opting a buddy for accountability, and laying out a framework for reaching an achievable* goal is important. Note, achievable has an asterisk next to it because my historical tendency is to set unattainable goals (scope too big, timeline too fast, stretched too thin). Note also, perfect has a carrot next to it to remind me that perfection is not something I truly want, and setting the metaphoric perfection carrot in front of me is NOT motivating at all (anymore) ☺️🍓 so while I know this year’s patch was an utter failure, I am learning more through my failures about my barriers to success, and what’s truly important in my life at this moment. 2️⃣ Extra tomatoes and better-late-than-never fly traps! 🍅🐛🙃 I have a big desire to give back to my community. So often, my partner and I start seeds from scratch and tend them in the haunt of the winter to someday be given away or sold to other gardeners in need. However, I failed to remember what the gardeners in our community garden really NEED. It was not participatory based research if you will, it was just convenient for ME because I had a lot of tomato seeds. Our community gardeners already have TONS of tomato enthusiasts. So obviously all our tomatoes didn’t go, and I failed to find a new home for them before they’d gotten too big for their pots. The fly traps are in response to not getting ahead of the chicken/fly larvae annual struggle. Now it’s kind of too little too late for mitigating the fly situation this season. This is a good example for me of complete ignorance on the matter. I oftentimes diffuse responsibility to my partner and don’t own up to my own part I can play. ☺️🐛🍅 So while I think about season planning for next year I will remember I can iteratively and continually improve the initiatives I have in place (funny, there comes that perfection sway again). Reminding myself of the impact my decisions can have on my community and the beings in my care can actually be a helpful reminder for what my vision of various initiatives can include. Setting goals that put me on a path to work towards that vision may be more motivating for me than the nuts and bolts of a particular initiative. 3️⃣ MY LOVE PLANT 💔🙃 I have always had a less-than green thumb when it comes to indoor plants. For my wedding anniversary this year I got an orchid to keep in our room. It was gorgeous and gave me much joy throughout the winter months. Then I don’t even know what happened but it died?! ☺️💔 this plant reminds me that I must appreciate each moment just as it is. The orchid served its purpose for its time in flourishing and then if I am too attached to its outcome, I may become extremely upset or start holding onto a limiting belief - such as that I am terrible with indoor plants. In actuality, the plant served its purpose and I am grateful for trying another indoor plant. It’s an attempt to stay open to whatever comes my way, even if it brings sadness (cause dang, those purple blooms were sad to see go). 4️⃣ Zinnia blooming hearty and strong 🌸☺️ I may have missed the blooms of other flowers as the season has progressed, but here I am today, noticing this beauty. 🙃🌸 it reminds me I was present today and mindful of the beauty around me - even if only for a moment. And then I realize how many other moments passed me by, so I breathe and remember to give myself grace. Each moment moving forward is another chance to be present, so maybe I’ll catch more of them if I let go of my striving so much. 5️⃣ bean blossom dance 💃🏼☺️ DANCE IT UP and let the wind run through my hair. My mom told a beautiful story this weekend about my brother’s first time on a bike without training wheels. She remarked how big his smile was and how he just looked like he was flying! 🙃💃🏼 OMG WHERE DID THAT CAREFREE INNER CHILD GO?!?! For me anyway?? My bro can still be pretty carefree :) On my bike home today I remembered that story and let myself go a little faster and release a little more tension as I let the work day melt off me in the wind. Envisioning these moments of release and letting them occur with some joy and movement for me has been just flippin DELIGHTFUL. 6️⃣➡️7️⃣ Jade Plant damage turned propogation. 🌪🙃This beaut was gifted to me by a dear friend and it is honestly one of my favorite plants in my care! This plant has already had a slight saga since it moved here but recently, a few dangling fronds dropped off. My partner learned he could try propagating! ☺️🌪 Physically turning a failure into new growth has no other need for explanation here, but I do want to say how much time I know these plants take to grow and propagate. AND my friend who gifted this to me says this baby comes from a long line of propagated plant siblings and aunts and uncles all the way to their mammoth grandmother of a jade plant. I only hope someday I have SOMETHING of a legacy to give to others, even if it’s a plant great grandbaby or some plant wisdom y’all will have in some weird millennial archive of social media use. Either way, the idea is planted (for legit lack of a better metaphor). 🙏🥰 thank you as always to my plants for inspo and insight 🌱✨ 💚 🥬 ♻️ https://www.instagram.com/p/B0R7F-eHhDE/?igshid=hmxhyjdhx5p

#amiright#plantwisdom#lifelessons#gardeners on tumblr#gardenfails#plantbabies#plantmama#gardeninspo#wellbeing#grow

0 notes

Text

Billie Eilish and the Pursuit of Happiness

New Post has been published on https://tattlepress.com/entertainment/billie-eilish-and-the-pursuit-of-happiness/

Billie Eilish and the Pursuit of Happiness

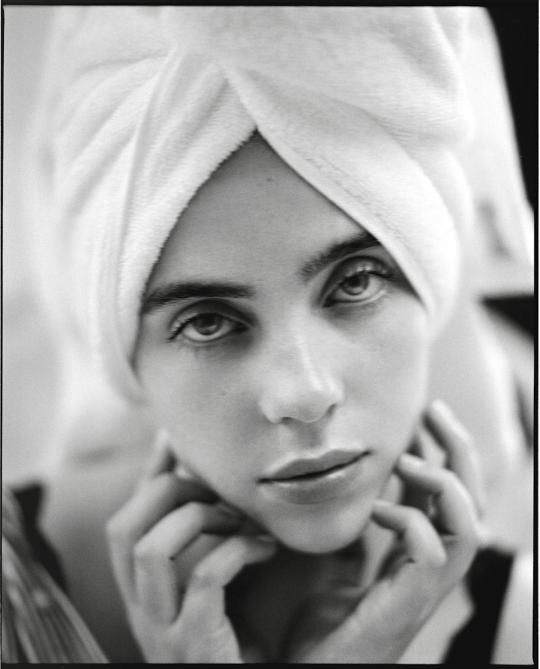

210413_ROLLING_STONE_06_1486_v4-billie-opener – Credit: Yana Yatsuk for Rolling Stone

From the outside, the house isn’t terribly different from others on the block: a cozy bungalow in L.A.’s Highland Park neighborhood with an old lilac tree blooming near the entrance. In fact, it’s legendary: the place where a prodigal teenager and her older brother recorded the album that made Billie Eilish Pirate Baird O’Connell the queen of Gen-Z pop.

It’s a location familiar to any Eilish fan, and at first glance on an absurdly beautiful day in April, not much appears to have changed about the house in the couple of years since it became famous, along with its teenage occupant. The O’Connell family’s rescue dog, Pepper, trudges through the backyard, now joined by Eilish’s year-old rescue, Shark, a gray pit bull. Signs of home-schooling linger in common areas, like an old-fashioned pencil sharpener attached to the wall and dingy supplies precariously placed on a desk.

More from Rolling Stone

But look closer, and plenty is different. For starters, contemporary pop’s most famous home studio, set up in the childhood bedroom of Billie’s brother Finneas, is no longer a studio. Instead, the siblings’ mom, Maggie Baird, has taken over the space. “It still looks similar. There’s just no equipment,” Billie insists as she greets me in her kitchen, gathering ingredients and utensils for the cookies she wants to bake. Her mom’s added a blue rug to the bedroom and sleeps there with their cat, Misha. “We kept [the studio] for a while, then we were like ‘We don’t need this,’ ” Eilish says.

Finneas moved out a couple of years ago, settling down in Los Feliz with his influencer girlfriend Claudia Sulewski. He constructed a new studio in his basement, where he and Eilish began recording music last year. Eilish is, at first, cagey about admitting that she’s moved out as well. “I’m secretive about what’s really going on,” she offers conspiratorially, rummaging around the cabinets of her parents’ kitchen like a college student visiting home on a long weekend. “It’s been a couple of years now where I’ve been doing my own thing. But secretly, because nobody needs to know that.”

Story continues

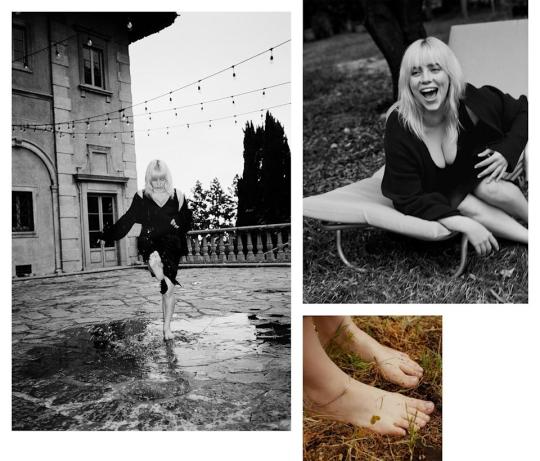

Eilish hasn’t been totally lying about where she lives; she still spends a lot of nights in her childhood bedroom. “I just love my parents, so I want to be around them,” she says, shrugging. Maggie and her husband, Patrick O’Connell, buzz in and out of the kitchen, commenting on the cookie baking and helping Eilish use the old oven. Eilish is sporting her new blond-bombshell look. A 180 from her formerly signature black-with-green-roots ’do, the new hair caused an uproar when she debuted it on Instagram in March. Today it’s damp from a shower, and she’s cozied up in a black T-shirt from her own merch store, along with a pair of matching sweats. On today’s menu are vegan, gluten-free peanut-butter-and-chocolate-chip cookies. She’s reading off an old recipe displayed on a food-stained printout that has clearly been well-utilized over the years. Eilish used to make them whenever she was sad. “It was a therapeutic thing for me,” she explains.

It’s been a while since she’s made the cookies (“You’re seeing history,” she teases). She’s found other ways to process her feelings, namely through writing her second album, Happier Than Ever, which is due out July 30th. The title is no fiction: She has, in fact, felt happier than she ever had before. But like a lot of things in her life, it’s not quite that simple.

“Almost none of the songs on this album are joyful,” Eilish explains, refuting the possibility that her second album is the bright, cheery counterpoint to 2019’s When We All Fall Asleep, Where Do We Go? The Babadook-inspired debut conjured up vivid memories of night terrors and lucid dreams over textures ranging from industrial electro-pop to jazzy ballads. Her videos were just as dark, full of spiders and black tears covering her face.

On the surface, Happier Than Ever is a different kind of nightmare. Emotional abuse, power struggles, and mistrust — stories drawn from Eilish’s life and the lives of people she knows — take up much of the lyrics, alongside musings on fame and fantasies of secret romantic rendezvous. The sound is mellowed out from the haunted-house sprawl of her debut: lush, somber, mesmerizing electronic soundscapes trickle down your spine, right along with Eilish’s words.

And yet, even on the darkest songs there are moments of reflection, growth and, most important, hope. This is an album from someone who began to heal long before she wrote it. Or at least tried to.

“Have you ever gotten stung on your head by a bee?”

Eilish mentions she got stung “like 20 times” on a camping trip when she was eight or nine. It’s a story she’s told before. “I don’t know why that popped into my head,” she says. “Why did that pop into my head? I have no idea.”

She posed the question after a bit of mesmerized silence as we watched Shark go to town on an empty can of peanut butter. Eilish doesn’t like silence; she even narrates the cookie baking like a food vlogger. She shows me how to make oat flour (“It’s literally oats on their own; pour them in this thing [a Vitamix blender], full power”) and figuring out the right chocolate chip to peanut-butter-dough ratio. (“Some people like too many. I like too little.”)

“I can’t go to the bathroom without watching something on my phone,” she says. “I can’t brush my teeth. I can’t wash my face.” Over the past year she rewatched a lot of things: Sherlock, The Office “probably like six times,” New Girl “like four times,” Jane the Virgin. There was also time for Good Girls, Killing Eve, The Flight Attendant, The Undoing, and Promising Young Woman “like four times.”

“It’s all on my phone,” she explains. She rarely watches anything on TV, except The Twilight Saga, which she took in for the first time recently, with a friend. “I just watch it while I do anything because it takes my mind off the reality of life. I should go on My Strange Addiction,” she says, coincidentally referencing her 2019 song of the same name (which, by the way, samples dialogue from The Office).

Eilish can’t really go outside anymore. There are paparazzi and creeps waiting for her every move, and some have threatened her safety to the point that she needed a restraining order against them. The instant recognizability of her When We All Fall Asleep-era look — bright-green hair, oversize clothes, saucer-like ocean eyes — helped keep her caged. She grew resentful: “I was a kid and I wanted to do kid shit. I didn’t want to be not able to fucking go to a store or the mall. I was very angry and not grateful about it.”

billie eilish rolling stone cover

When We All Fall Asleep and the image she projected at the time marked her uniqueness from the rest of the pop world. But those things also cemented a view of her she’d love to leave behind. I mention an instruction during a musical challenge on a recent season of RuPaul’s Drag Race where a competing drag queen was told the song she was performing was “very Billie Eilish.”

“What do they think when they think that? Do they think what the internet thinks, which is whispering or whatever the fuck people say? Anytime I see an impression on the internet, it just reminds me how little the internet knows about me. Like, I really don’t share shit. I have such a loud personality that makes people feel like they know everything about me and they literally don’t at all.” She wants people to understand a few things: “That I can sing. That I’m a woman. That I have a personality.” Happier Than Ever offers a statement on all of the above.

“Anytime I hear somebody say, ‘Oh, your songs sound the same,’ it gets me. That’s one thing I really try hard to not do. I think the people that say that have literally only heard ‘Bad Guy’ and ‘Therefore I Am.’ ” Both of those songs feature Eilish’s tendency for muted, moody sing-rapping. These days, she’s channeling the jazziness in her voice, a timbre honed from years of touring, on songs like “My Future” and “Your Power.”

Eilish’s privacy was more precious than she had initially realized. She put a lot of herself out for the world to consume early in her career, when she was an “annoying 16-year-old” (her words) trying to engage with her fandom the way she wanted her favorite artists like Justin Bieber to do back when she was a preteen fan. “It’s sad because I can’t give the fans everything they want,” she says. “The bigger I’ve gotten, the more I understand why [my favorite celebrities] couldn’t do all the things I wanted them to do.”

She struggles to find the right way to frame it. “It wouldn’t make sense to people who aren’t in this world. If I said what I was thinking right now, [the fans] would feel the same way I did when I was 11. They’d be like, ‘It would be so easy. You could just do it.’ No. It’s crazy the amount of things you don’t think about before it’s right in front of you.”

Eilish describes her life as “normal as hell,” and at times, it is. She’s watching Twilight. Going on first dates again, as discreetly as possible. Getting first tattoos (she got a giant black dragon on her right thigh in November and “Eilish,” in an ornate, gothic font, in the middle of her chest the day after the 2020 Grammys). “That’s why it’s hilarious when I see, like, ‘10 reasons why we think Billie -Eilish is in the illuminati,’ ” she says. “I’m like, you know how regular I am, dude?”

She wants to share more details with her fans, but the thought makes her nervous. The songs on Happier Than Ever are buzzing with the fear of “interviews, interviews, interviews,” of the names of abusers or toxic friends being forever tied to her, of her own words coming back to haunt her.

“I wish that I could tell the fans everything I think and feel and it wouldn’t live on the internet forever. And be spoken about and called problematic, or called whatever the fuck anybody wants to call any thoughts that a human has,” she explains. “The other sad thing is that they don’t actually know me. And I don’t really know them, but obviously we’re connected. The problem is you feel like you know somebody, but you don’t. And then it’s like, yeah. It’s just a lot.”

We move outside, to the sole picnic table in the yard, and enjoy the warm, crumbly peanut butter cookies. Shark finds a particularly bright patch of sunlight to lie in. Suddenly, he hops up and runs along the fence, in response to the barks of a neighbor’s dog that he desperately wants to befriend. Eilish is a bit jealous.

“Don’t you just wish that was you?”

billie eilish rolling stone cover

“My mom was saying this yesterday,” Eilish says. “When you’re happier than ever, that doesn’t mean you’re the happiest that anyone’s ever been. It means you’re happier than you were before.”

After an adolescence plagued with depression, body dysmorphia, self-harm, and suicidal thoughts, Eilish started feeling better in the summer of 2019, while on tour in Europe. It was shortly after the release of When We All Fall Asleep, and she was seeing a therapist, had just broken up with a boyfriend, and was joined on the road with one of her best friends (as well as, of course, her parents and brother). “I was thriving,” she says. “I felt exactly like who I was. Everything around me was exactly how it was supposed to be. I felt like I was getting better. I felt happier than ever. And I tried to continue that.”

Early 2020 was a whirlwind. Eilish swept the Big Four categories at the Grammys and started a headlining tour that would have eaten up most of her year. She was more excited than she had been for previous tours, which left her with sprained ankles, shin splints, and chronic pain. She played all of three dates before the pandemic forced her to cancel the rest.

Eilish kind of got to say goodbye to the When We All Fall Asleep era (and the look that helped make her famous) at the Grammys this year, performing the one-off single “Everything I Wanted” with Finneas. Happier Than Ever was nearly complete, but she wasn’t yet ready to show off her new blond look. So she hid it beneath a green-and-black wig. “It was weird,” she reflects. “I was playing this former Billie Eilish with green hair, singing a song from a year and a half prior, while I have 16 new songs that I haven’t put out yet. The fans didn’t really even know that it was a goodbye to an era. That’s kind of heartbreaking but endearing at the same time.”

Recorded as the world went on pause, Happier Than Ever was an opportunity to dig into her personal trauma. “I went through some crazy shit, and it really affected me and made me not want to go near anyone ever,” she says, though she declines to give details.

Like everything Eilish does, the lyrics are sure to spark debate, side-eye emojis, and conspiracy theories as people ponder who she’s singing about. The songs are a mosaic of experience, ripped from her own life and those of people she knows. They juggle deadbeats, secret lovers, emotional abusers. Eilish won’t name names or get into specifics, and she’s quick to remind that this is not just her life she’s talking about. But she also says the stories in the new songs are more honest than When We Fall Asleep, which she describes as “almost all fictional.”

Eilish says she’s letting go of the Old Billie, who would tuck away her own emotions to make others feel better. “There’ve been times where I’ve been really affected by somebody, and I said to them, ‘I need to tell you how you’ve made me feel.’ And they said something that was like, ‘I can’t handle this right now. I just can’t handle this right now. This is going to be too much for me.’ ”

She says she spent so long “being fucked with” and had to realize that while the toxic traits she sings about were often born out of pain, that doesn’t make it OK. “I was talking to a friend about their life, and they told me all this crazy traumatizing shit that happened to them. And I’m like, ‘Oh, right, you don’t have to treat everyone like a piece of garbage, just because you’ve been hurt.’ It’s OK to be traumatized by something and have bad instincts, but also, there’s no excuse for abusing people. There just is not. I feel like everything is excuses all the time. Excuses, excuses.”

Album opener “Getting Older” was particularly harrowing to write. “Wasn’t my decision to be abused,” she sings over a delicately plucking synth beat. By the end, she lays bare what’s on her mind. “I’ve had some trauma/Did things I didn’t wanna/Was too afraid to tell ya/But now I think it’s time.” Eilish recognizes how shocked listeners may be by the rawness of the song. “I had to take a break in the middle of writing that one, and I wanted to cry, because it was so revealing. And it’s just the truth.”

The title track, which starts like a mopey breakup song, then fires off into an electric-guitar-driven rager, was the first thing she started writing for the album, back on the European tour where she felt like she was thriving. The rest of the songs bare different kinds of catharsis, teetering between sexy, electronic beats and warm folkiness, reminiscent of her earliest music. Each song is delicate, sensuous, and balancing naked vulnerability with a bit of self-protective confidence posturing.

Writing about her deepest emotions wasn’t easy for someone who had painstakingly kept the details of her relationships under lock and key. “I’ve been in two [relationships],” she says. “I’ve experienced a lot in what I have done. But I’ve never been in something really real and normal.” The news cycle and fan response to her Apple TV documentary, The World’s a Little Blurry, earlier this year cemented her decision not to name names or get specific about details in the new songs. People are like “ ‘Well, you’re an artist, so when you put something out there like that, you can’t expect people to not dive into it more.’ Yes I can,” she says. “You should absolutely respect me giving you this much information and saying, ‘This is all you get.’ The rest is for my own brain.”

billie eilish rolling stone cover

The most the world has gotten to see of Eilish’s romantic life was in The World’s a Little Blurry, which spanned from the final weeks of recording When We All Fall Asleep in late 2018 through the 2020 Grammy Awards. Eilish wasn’t necessarily psyched for it to come out. “I don’t like to share that part of my life, and I was not planning on sharing that part of my life ever,” she says.

Her ex, Brandon Adams, an artist who performs under the name 7:AMP, played a pivotal role in the film. The World’s a Little Blurry showcases a painful give-and-take between Eilish and Adams, who was then in his twenties. In the aftermath of the documentary, fans went after Adams and his family on social media.

Many have assumed Eilish’s chilling single “Your Power,” which mentions a relationship between a teen girl and an older man, is about Adams. Eilish — who released the song in late April, along with a statement saying, in part, “this is about many different situations that we’ve all either witnessed or experience” — strongly objects to this notion. “Everybody needs to shut up,” she says. The documentary, she insists, “was a microscopic, tiny, tiny little bit of that relationship. Nobody knows about any of that, at all. I just wish people could just stop and see things and not have to say things all the time.”

Eilish describes herself as “clingy,” but since she and Adams broke up in 2019, she’s spent the past two years trying to learn how to exist on her own. “I didn’t know how before,” she explains, “which is ironic because I had never been in a relationship that allowed me to really exist with that person anyway. My emotion always is because of somebody else’s, and that had been such a big pain in the ass.”

She’s still trying to grow out of that. “You heal eventually.”

Eilish and I actually weren’t supposed to meet at her parents’ house. She wanted me to see where she recorded Happier Than Ever, in Finneas’ basement studio. But a pipe burst, nearly destroying the space. “The room had to be completely rebuilt,” he explains later over Zoom. “But my hard drives, synthesizers, and guitars and stuff were all fine. I feel very lucky for that.”

Eilish speaks with relief at how much less draining the recording process for Happier Than Ever was compared with her debut. It was partially due to some peak-mom advice from Maggie early in the pandemic. After nearly a month of lockdown, Maggie suggested that her kids get on a weekly schedule. Every Monday, Wednesday, and Thursday, Eilish would drive her matte-black Dodge Challenger over to Finneas’ house. Some days they would write songs. Other days they’d play Animal Crossing or Beat Saber. Every day they would eat good meals: “A lot of Taco Bell, homemade pizza, taro boba, Thai food,” Eilish lists. “Crossroads and Little Pine. Nic’s once. Fatburger once. It was such a reward.”

In The World’s a Little Blurry, the teen’s misery is palpable as she finishes When We All Fall Asleep. Eilish and Finneas had been largely left to their own devices, but pressure still loomed from the label. There were deadlines (the album was due right around her 17th birthday), constant meetings, and an expectation that a star was about to be born, thanks to a couple of years of growing buzz. “I hated every second of it,” she admits. “I hated writing. I hated recording. I literally hated it. I would’ve done anything else. I remember thinking there’s no way I’m making another album after this. Absolutely not.”

This time, there was no pressure. No notes from the label. No meetings. No rush to meet deadlines. “No one has a say anymore,” Billie says. “It’s literally me and Finneas and no one else.” On April 3rd, 2020, the first day of their new weekly work schedule, they wrote “My Future.” Within a couple of months, they realized that they were making an album.

She pulls out a clear acrylic sign holder with the track list written in marker, songs clearly erased and moved around. “I think I’m going to frame this,” she says, smiling. There are some water stains on it, since it got drizzled on when Finneas’ studio flooded.

The 16 songs on the album are the only 16 they worked on. The pair are completists: Once they start a song, they have to see it through with meticulous precision until it’s perfect to them. The way the album sounds is a testament to that, each song a unique, avant-pop soundscape that elevates the baroque trip-hop-ness of her debut.

billie eilish rolling stone cover

“I admire artists that can make, like, three songs in a day and keep doing that over and over,” Eilish muses. She compares songwriting to running, in that it would be “fucking exhausting” to do all the time. “Songwriting is like that for me. I’m pretty good at it, but it takes a lot out of me. I feel like I just ran a marathon whenever I write a song.”

Finneas saw the change in his sister this time around. She liked writing songs, feeling less tortured by the process than before. “It’s been awesome as a big brother to see her become more confident and feel more ownership and just to be more excited than I’ve ever seen her about the music that we’re making,” he says. “I also just think she has objectively gotten even better. That’s my opinion. If she were an Olympic gymnast or something, she would’ve gotten better. She’d be able to do a higher vault or something.”

Since “Bad Guy,” Finneas has become one of pop’s most in-demand producers, working with everyone from Tove Lo to Selena Gomez. He also has his own solo career that’s taken off, though the studio flood came at the worst time possible for it, as he was working on his debut album. Eilish has found Finneas’ career outside of being her creative partner to be “fucking great” and easy for them to adjust to. “It doesn’t interfere at all, and it’s fun for him,” she says. “He only does what he wants to do. He’s not a slave to it.”

“I scratch a lot of itches working with Billie,” Finneas continues. “I think my primary goal was to just go deeper. This was Billie’s sophomore album, you just . . . you have the opportunity to go further inward and further down in your Mariana’s Trench.”

Finneas says that their process is “50-50” creatively, and he speaks proudly about the gated tremolo and distortion that elevate songs like “Oxytocin” and “NDA,” two tracks that look at romance and hookups through the lens of a very famous person attempting to have both under the radar.

“Billie Bossa Nova” takes that theme one step further, building a fantasy around the life of a touring pop star. “We have to do a lot of goofy bullshit when we go on tour, where we enter through freight elevators in hotels and stuff, so that paparazzi doesn’t follow us to our room,” he explains.

“And so we acted as if there was also a secret love affair going on in there of Billie being like, ‘Nobody saw me in the lobby/Nobody saw me in your arms,’ as if there was a mystery person in her life during all of that.”

“I write songs with my brother, and we kind of have to plug our ears when we’re writing about desire for other people because we’re fucking siblings,” Eilish says later. Songs like “Oxytocin,” named for the hormone released in the bloodstream due to love or childbirth, has her wondering “What would people say . . . if they listen through the wall?” over a slinky beat. The folky “Male Fantasy” features her distracting herself with pornography, then meditating on the effect porn has on men.

“The thing is, we’re very open about both of our lives, so it’s not weird, really,” she continues. “It’s just fun. It’s songwriting and it’s storytelling. We just have to think about the art of it and not think too hard about [the lyrics].”

As 50-50 as they are, Finneas drives home the fact that everything is under Eilish’s name for a reason. “In many instances we’ve been asked about our relationship as a duo when it’s billed as a solo artist,” Finneas says. “It’s her life. It’s all her world. I’m helping her articulate that, but it’s really her experiences that she lived through, and on this album she let me into it a lot. But I don’t know what that’s like to go through.”

He quotes his friend, the singer-songwriter Bishop Briggs, who says writing is how she copes with everything. Finneas agrees. “Billie making this album was her working through a lot of this stuff.”

When Eilish releases a new song, she can’t listen to it again. It disappears into the universe, only to be heard by its maker if she happens to catch it as it’s played on radio every hour on the hour. “It’s not because I don’t like it anymore,” she explains. Happier Than Ever has become Eilish’s favorite album in the world, but she’s already mourning the loss of it, months before it even comes out. As we talk, it’s a couple of weeks before the first single is even public knowledge.

“I don’t know how to explain this, but all the songs on the album feel like a specific time, because they feel like when I wrote them and made them,” she explains. “It’s so funny that to the rest of the world it’s going to feel like a certain moment for them, and it’s going to be so different than mine. That’s such a weird, weird thing to wrap my head around. And I will fucking love it. I love it. That’s the reason you do this. It’s for that.”

When Eilish and I speak one last time, “Your Power” has been out for a few days. It spurred reflective conversations online, with many women sharing their own experiences with sexual or emotional abuse. The lyrics about an older partner taking advantage of a younger woman struck a particular chord, and Eilish herself is still processing that reaction.

billie eilish rolling stone cover

“I feel like people actually really, really listened to the lyrics,” she says, flopping around her room in an oversize Powerpuff Girls shirt. “I was scared for it to come out because it’s my favorite song I’ve ever written. I felt the world didn’t deserve it.”

She broke her own Instagram “like” record that weekend as well: Her shoot for British Vogue showed her in more revealing clothes than she had ever been pictured in, channeling Forties boudoir shoots. The images were a topic of internet obsession for days: Was it a betrayal of her more “modest”-seeming fashion before? Did she make the decision herself? But it’s not like her body hadn’t been up for debate even when it was clothed: Her baggy outerwear was used to shame her peers, and she was subjected to belittling, fatphobic assumptions from the too-curious. “I saw a picture of me on the cover of Vogue [from] a couple of years ago with big, huge oversize clothes [next to] the picture of [the latest Vogue]. Then the caption was like, ‘That’s called growth.’ I understand where they’re coming from, but at the same time, I’m like, ‘No, that’s not OK. I’m not this now, and I didn’t need to grow from that.’ ”

Like her fashion experiments, Happier Than Ever is not about resetting who Billie Eilish even is. It’s about expanding the definition and range. But like she feared, she stopped listening to “Your Power” after it came out. “I don’t know. Something changes,” she says, still confused by her own habit.

The song has already taken on a life of its own, so she doesn’t have many expectations for how people will react to the rest of the as-yet-unheard songs. She’d like to make a visual for each track, and plans to embark on a world tour at some point.

She has one other wish for her new music. “I hope people break up with their boyfriends because of it,” she says, with only the slightest tinge of humor. “And I hope they don’t get taken advantage of.”

Best of Rolling Stone

Source link

1 note

·

View note

Photo

New Post has been published on https://usviraltrends.com/a-babys-murder-opened-a-dark-chapter-in-ireland-that-still-hasnt-been-closed/

A baby's murder opened a dark chapter in Ireland that still hasn't been closed

Cahersiveen, Ireland — At the edge of an Irish village lies a cemetery nestled between lush hills and the craggy shores of the Atlantic. Under an umbrella of iridescent clouds, Catherine Cournane makes her way toward the back plots.

She meanders past the grave of her mother, two brothers and a cousin. She visits them often here in Cahersiveen’s Holy Cross Graveyard. But on this day, she is here for someone else.

Baby John.

It has been two days since Catherine last tended his grave and at the headstone, she sees fresh chrysanthemums. Their yellow and orange petals have weathered the pelting rain and wind. Catherine wonders who left them there.

Other babies are buried at Holy Cross and their loved ones look after them. But Baby John has no one.

So, Catherine took on the task of looking after the grave. She felt compelled to make sure Baby John rested in peace. He deserved that, Catherine thought, after the ugliness that had surrounded him.

Catherine Cournane at the Holy Cross Graveyard in Cahersiveen.

Baby John’s headstone reads: “I am the Kerry Baby.”

Catherine was 15 when the tragedy unfolded.

She was in high school when Baby John died 34 years ago and she had helped carry his tiny casket to the graveyard. She was there when hundreds of schoolchildren stopped off to pay their respects with prayer after school. She joined the children when they burst into spontaneous song at the infant’s grave.

In Ireland, it wasn’t unusual for a community to gather around a loss of their own. But Baby John’s funeral was different.

Catherine did not know who the baby’s parents were. No one did. Still, no one does.

His three-day-old body had been found on a rocky stretch of beach on the outskirts of town. He had been strangled and stabbed 28 times.

But what Catherine does know is this: A baby was laid to rest on a spring day more than three decades ago and nothing would ever be the same again.

The sordid saga that unfolded would shake Catherine, her community and her country. And it would force Ireland to confront the bitter truth on how it treated its women.

In spring of 1984, Catherine was 15 and living at home with her parents and six brothers and sisters in Cahersiveen. The town’s 1,300 people had the good fortune of residing on a stunning spit of coastal land in southwest Ireland’s County Kerry that felt like the edge of Europe. It very nearly is.

Back then, everyone knew one another and if they didn’t know someone, they’d at least know of them. Police stopped residents for missing lights on bicycles but rarely anything more.

That was until Baby John.

A runner had discovered the newborn’s body on the beach and the gardai, as the Irish police are known, called Catherine’s father to the scene of the crime. Tom was an undertaker and Catherine had been surrounded by death all her life. But she took notice that night.

Tom christened the baby with water from a nearby freshwater stream. He named him John and placed him in a tiny casket. Catherine stared at it on the back seat of her father’s car. It was the smallest she’d ever seen.

She knew the circumstances of the baby’s death. She knew the police were hunting the killer; that they suspected the baby’s mother.

A couple of weeks passed. Then, one afternoon, as daffodils were beginning to break through winter soil, Catherine cycled home, down familiar lanes, to find two men waiting for her in the sitting room.

They were the police and Catherine knew exactly why they were there.

Do you have a boyfriend? they asked Catherine.

No.

Do you know anyone who does have a boyfriend?

Yes.

They asked if any of those women had been pregnant and if Catherine had heard any gossip about anyone having an affair with a married man.

No, she replied.

Catherine nearly fainted from the gardai’s questioning. She thought of herself as a “good girl,” and her mother did too. The police had brought fear into their home.

But in 1984, fear was the norm in Catholic Ireland.

Although a referendum a decade before had drastically reduced the Church’s political sway, its patriarchal weight still came down on aspects of society.

The Church crafted the curriculum for nearly all state schools and sex education was practically non-existent for girls like Catherine.

Her only exposure to sex was a box of condoms a relative once brought home as a souvenir from England. She kept the contraband hidden away, and included one as a gag gift for a friend’s birthday. When her mother found out, she got a wallop.

Condoms required a prescription and birth control pills were available only to married women if they were able to find a doctor to prescribe them.

Women found themselves raising smaller families than their mothers’ generation; yet Ireland still held one of the highest fertility rates in Western Europe. In decades prior, unmarried women who became pregnant would disappear “on holiday” for months. More likely, they were sent to church-run homes to deliver babies that would be given up for adoption, a practice for which the Church has apologized in recent years. The last mother and baby home only shut its doors in 1996.

The women would return home to silence. No one dared to ask questions.

There were few ways out for women who felt stuck in oppressive marriages; divorce was illegal and would be so until 1996.

Irish women had little say over their bodies. The state was in control. It was in this environment that the Baby John investigation unfolded.

A road leading to White Strand, the beach where Baby John was found.

At Catherine’s home in Cahersiveen, the gardai pressed on with questions.

How could you be coming to talk to me about this? she thought. My God, I’m only 15 and I haven’t done anything.

After Catherine, the police moved on to the next young woman. And then the next. They were interrogating nearly every woman of childbearing age on the Iveragh peninsula.

Brigid, whose name has been changed to protect her identity, was one of them. She was 24, single and working in a neighboring county. One weekend, she returned home to Cahersiveen to visit her parents and found the police waiting.

She has never forgotten the way one of the police officers examined her body. She felt his eyes burning through her.

She had never taken any chances and would never have become pregnant. Her parents raised her in the Church and she knew pregnancy before marriage would have amounted to a death sentence. She’d seen the fate her aunt suffered after becoming pregnant out of wedlock. Her aunt was thrown out of the house and never seen again. She had, like so many other Irish women, been erased.

At the time, the line of questioning young women like Brigid and Catherine experienced was not so shocking. Irish authorities were pushing back against significant gains made by women’s rights groups including the abolition of a law that prevented married women in civil service from working as well as campaigns for equal pay, equal rights and access to contraceptives.

None of it sat well with conservatives who saw the advances as a threat to Ireland’s traditional way of life.

Road signs in Cahersiveen town.

Religious figurines and “Rally to Save the 8th“ posters seen through a window in town.

The Cahersiveen Garda station.

A backlash was evident when over a million people welcomed Pope John Paul II to Ireland in 1979. To some, including Mary McAuliffe, a lecturer at University College Dublin, the Catholic leader’s teachings that contraception was immoral, divorce was unconceivable and a woman’s role was at home played a part in reversing some of the gains women had made.

In 1982, a schoolteacher was fired after becoming pregnant out of wedlock with a married man; two years later, Ireland’s Supreme Court ruled children born out of wedlock had no succession rights.

In September 1983, a referendum was called to constitutionally ban abortion, already illegal in practice.

Church and state blurred into one, culminating in anti-choice rhetoric, including a comment from a County Galway bishop who reportedly said the most dangerous place for a baby is in the mother’s womb.

The abortion referendum passed with a two-thirds majority and the Eighth Amendment to the Irish constitution provided the unborn with an equal right to life as the mother.

Women lived under pervasive fear. Shortly after the Eighth Amendment was passed, a 15-year-old girl, Ann Lovett, became pregnant and died in a grotto. She had gone there to secretly give birth, under a statue of the Virgin Mary.

Lovett died around the same time police were interviewing Catherine, Brigid and scores of other women in the Baby John case.

Soon the police had a suspect. Her name was Joanne Hayes.

Joanne had given birth to a boy the day before Baby John’s body was found on the beach.

She delivered her child alone on her family’s farm in Abbeydorney, a tiny town less than two hours’ drive from Cahersiveen.

Joanne lived on that farm with her infant daughter, mother, aunt and siblings. She worked as a receptionist in a newly built gym in nearby Tralee, where she met the father of her children, Jeremiah Locke.

The relationship was far from typical. Jeremiah was married and had children from another marriage. And even though abortion was illegal in Ireland, adultery was not.

Still, Joanne concealed her pregnancy from her family and coworkers. It was, like the relationship, an open secret.

By the time Joanne went into labor, the couple had broken up and Jeremiah was no longer by her side when she gave birth. It’s not clear if the baby was stillborn or whether he died soon after. Only Joanne knows.

What is known is that she was a grieving mother who wanted to keep the ordeal to herself. Quietly, she buried her son in a field at her family farm.

But Joanne needed medical care and checked into a nearby hospital.

The Baby John investigation was going nowhere and after the police saw Joanne’s name on a registry of new mothers, they pursued a theory connecting her to the murder that, court documents would later show, was “inexcusable.”

She was brought in for questioning by detectives. For most of Joanne’s life, the gardai had earned an intimidating reputation. Just a few years before, Amnesty International had published a report alleging “systematic maltreatment” of suspects, including “oppressive methods of extracting statements.”

Joanne told them she could prove she was not Baby John’s mother and pleaded with them to take her back to the baby’s grave. But the gardai refused and threatened to throw her in jail and her daughter in an orphanage.

Intimidated and scared, Joanne relented and told the police what they wanted to hear: she had killed Baby John and disposed his body at sea. Her family went along with the falsehood.

The truth would take more than three decades to surface.

As the police pressed on, Joanne was moved from jail to a psychiatric hospital. There, she finally convinced police to recover her baby’s body at the farm. The police now had two dead babies to account for.

They bandied about the idea of “heteropaternal superfecundation,” a medical anomaly suggesting Joanne had been pregnant with twins by two different men.

But Joanne’s blood work proved she couldn’t have been Baby John’s mother. The police were forced to drop the charges.

After the charges were dropped, Joanne and her family reported allegations of police abuse, both physical and psychological — but the findings of an internal police investigation were inconclusive.

Public outcry prompted a probe into the gardai’s behavior but that quickly devolved into a trial of Joanne’s womanhood.

Joanne Hayes at the Tribunal of Inquiry in Tralee, County Kerry, in 1985. Michael MacSweeney/Provision

Women demonstrate in support of Joanne Hayes outside the Tribunal. Michael MacSweeney/Provision

For months, Joanne and her family’s private lives were put on public display at a tribunal, with scores of male officials taking turns to assassinate her character according to the court documents.

A legal team showed maps where Joanne and her lover had been intimate; a doctor detailed the size of Joanne’s birth canal; male psychiatrists aired their opinions on her personal character. One even said that Joanne didn’t appear to be guilt-stricken enough at the death of her own child.

The judge ordered sedation for a visibly upset Joanne and in this state, she took the stand to testify.

Joanne’s sole consolation was that from her tragedy grew support from women across the country. They rallied outside the court and sent Joanne yellow roses as a symbol of solidarity. They wrote letters and cards to her, detailing their own stories of suffering.

The support was solace for Joanne but justice eluded her.

In 1985, the tribunal absolved the police of wrongdoing. The officers central to the case were all eventually promoted.

But those officers never apologized.

She returned home to Abbeydorney and shrouded herself in a cloak of privacy. For 34 years, she has lived there, out of the limelight.

Baby John’s killer was never found.

For all these years, Catherine has carried the story of Baby John with her. At his grave, she dreams of the life he might have lived. Or not.

If contraception had been readily available, maybe he would have not been born at all. If society had allowed for a more open conversation about sex, he might still be alive. Maybe he would have grown to have a family of his own.

Catherine thinks about her own family.

She raised an 18-year-old daughter in a home without taboos, one that celebrated women. She raised her to become a woman no one would dare mess with.

Catherine wanted to make sure her daughter never experienced what she had.

She’d lost her innocence the day her father brought home Baby John’s body. She was shocked when she learned about Joanne and how she was treated, though, looking back, she realizes it was that moment that cemented her commitment to women’s rights.

Catherine never forgot that the blame in the Kerry babies case had fallen on a woman. No men were ever at fault.

Irish society has seen significant social changes since then. The Church has lost much of its moral authority, rocked by cases of scandal, sex abuse and the discovery of a mass grave of babies born out of wedlock in Tuam.

The small ripples of change that feminists won in the 1970s and ‘80s have since swollen into waves of protest on Ireland’s shores.

In 1992, the landmark X Case made it legal for Irish women to travel abroad for abortions, adding the threat of suicide as grounds for abortion.

In 2013, Savita Halappanavar died of sepsis after being denied a termination of a miscarrying fetus in a Galway hospital, prompting the government to pass a bill allowing abortions when a woman’s life is in danger.

And in January, 34 years after Joanne was wrongfully accused, the police finally issued her a formal apology. They admitted that DNA conclusively ruled that she could have not been Baby John’s mother. They also announced they would reopen the Baby John case.

But for Irish women like Catherine, none of it is enough.

No apology or monetary compensation, she believes, could ever make things right for Joanne.

Catherine realizes that Irish attitudes have changed. Still, she knows many people in Ireland remain reluctant to talk about the Kerry babies saga. And the tribunal transcripts remain restricted to the public.

“It’s about time for Ireland to wake up and shake itself and say this was wrong,” she says.

Catherine says she was too naive, too powerless then to realize she might have been able to put an end to what has been described as a “medieval witch-hunt.”

Brigid has come forward on her own volition and Walter Sullivan, the detective leading the new investigation, says it’s standard protocol to go back to everyone. That could include Catherine.

The police won’t comment on the case, except to refute the notion that only women are considered suspects. O’Sullivan says the renewed probe focuses on DNA samples that might help identify Baby John and his parents.

For many women here, a familiar pattern is again unfolding.

Ireland is again calling a referendum on abortion. And the pope is again scheduled for a visit. Only this time, his visit will come after the vote.

And this time, Catherine is certain Irish women are more aware of their rights than before.

They will have a chance to voice their opinions when they cast their votes in a May 25 abortion referendum, hailed by many, including the prime minister, as a critical step for women’s rights in Ireland.

While her nation stands poised to make history, Catherine spends her time in Cahersiveen, with her daughter and her ailing father. At 88, he has grown frail and is no longer able to look after Baby John’s grave.

The headstone has been destroyed several times and Catherine and her family are fearful that new interest in the Baby John case will once again bring trouble.

On this misty afternoon, Catherine plucks weeds poking out of the gravel, cleaning the grave as though it held one of her own.

Baby John would have been 34 this year.

As Catherine leaves the grave, she sees a plush bear sullied in the mud near the cemetery gate. Its knees are bent as in prayer, its eyes closed.

Ireland apologized to Joanne Hayes but Baby John never found his peace, Catherine believes. And without a fair investigation, he will never have that peace. She feels fairly sure the baby’s real mother still lives nearby. She hopes that woman can one day come forward without shame or fear.

“Our community is still dealing with a dark secret of the past,” she says.

The only way to move forward, Catherine believes, is to absolve the mother.

Then, perhaps, Baby John will be able to finally rest.

(function(d, s, id) var js, fjs = d.getElementsByTagName(s)[0]; if (d.getElementById(id)) return; js = d.createElement(s); js.id = id; js.src = "http://connect.facebook.net/en_US/all.js#xfbml=1"; fjs.parentNode.insertBefore(js, fjs); (document, 'script', 'facebook-jssdk'));

0 notes