#humorproduksjon

Text

Storyclock vs. Story formula

The Storyclock from Plot Devices, originally launched as a Kickstarter campaign in 2017, resembles Dan Harmon’s story formula (which I mentioned in this post, but still haven’t written about... oh, and read a useful writing advice from Harmon here).

Oh, and this is a pretty long post with many pictures, so I’ve split with a “Read more”-section.

Okey, so let’s take a side track, and first explore...

Dan Harmon’s story circle

Dan Harmon explains his approach to storytelling in a multipart series on the Channel101 wiki-page:

Story Structure 101: Super Basic Shit

Story Structure 102: Pure, Boring Theory

Story Structure 103: Let's Simplify Before Moving On

Story Structure 104: The Juicy Details

Story Structure 105: How TV is Different

Story Structure 106: Five Minute Pilots

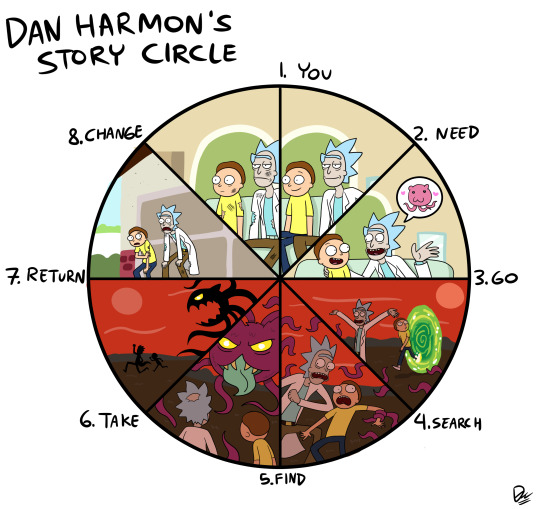

This is really mandatory reading for anyone interested in modern day storytelling. The creator of genre bending and fan-inducing shows like Community and Rick and Morty (explored in the early days of this blog), clearly has a strong sense of the inner drives and mechanisms of a well-designed story. So it has been defined as this (illustration via tredlocity):

A character is in a zone of comfort,

But they want something.

They enter an unfamiliar situation,

Adapt to it,

Get what they wanted,

Pay a heavy price for it,

Then return to their familiar situation,

Having changed.

I first came across this model in a WIRED-article about Dan Harmon from 2011 which describes the model in much detail.

Later, I’ve seen many videos describing the model, and it even has its own Wikipedia chapter in his name, where sitcom writer Graham Linehan is quoted explaining it as “basically a distillation of the 'hero's journey' idea”. It is quickly explained by the master himself here:

youtube

Alright... so back to...

The Storyclock

The tool was originally developed as a notebook, equal parts research oriented and development oriented. I first came across it through a Film Riot video with the creator where it is described as “A Writer’s Cheat Code”.

youtube

The claim is that this model not really limited to screenwriting, but relates to all kinds of story, irrespective of format – including everything from novels, to blog posts, powerpoint presentations and book reports. There are many universal story structures, ranging from Aristotle and Vladimir Propp, to Joseph Campbell, Blake Snyder – and the Pixar emotional structure, that deserves a separate post some day.

What I find fascinating about this particular model, is its dynamic structure.

Step 1: Set up the clock

Step 2: Fill in your plot

Step 3: Find the symmetry

Step 4: Let your story grow

Why use a model like this?

What’s different about the circular story templates – and to be honest, The Hero’s Journey (as described by Joseph Campbell, mentioned earlier in this article) is also circular and not that different from these other models – is that it lends itself well to episodic narratives, such as television. This point is especially important to Dan Harmon.

These story clocks, circles and models allow us to take a step back, identify the essential components and find the themes and through-lines of a story. This is not meant to be limiting (in my view, at least), and function as a “locked set of story rules”, but a way to explore, investigate and discover what the story is and can be. It allows us as authors to take a step back, clarify the story progression and build up to the themes in a way that is also mentioned in the previous post, with a video essay about The Good place – where this sitcom is applauded for its clarity of storytelling where themes are shared across storylines within a single episode, providing a stonger structure, more satisfied audience experience and a clearer vision... maybe?

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Search Party – pilot breakdown

So I decided to do a breakdown of the Search Party pilot episode, by comparing the pilot script (available here) and the televised episode (currently streaming on HBO Max).

I am fascinated by these dark comedies – or what has been coined “post comedy” (see this and this blogpost on the same topic) – which isn’t really *funny*, but *humorous*. There is a fine line between what qualifies Search Party as a comedy, and what qualifies Breaking Bad as a drama. To me, it seems to be grounded in delivery, pacing, the characters, and their relationships. The dark “post comedies” seem to follow an Aristotelian tragic structure populated with comedic characters. This is definitely worth exploring further, but time to get back on track with the Search Party analysis.

Differences between the script and production

The subway sequence and YWCA conference meeting (pp. 1–4), as well as the the Dory/Chantal backstory (p. 6), are not in the pilot.

The bathroom scene (pp. 10–11) is moved after the rooftop party (pp. 12–17), and the scene in the liquor store (pp. 11–12) is dropped.

The scene in Paulette’s office (pp. 17–18) and Dory’s meltdown scene (pp. 18–19) seemed to have been cut, but I suspect this is more of a thing that happened in post to match the performances, rather than a planned script change.

Elliott’s yoga scene (p. 20) and Drew’s meeting with April in the hallway (pp. 20– 21) were dropped from the pilot.

Dory’s surprise visit to Eirick – later renamed Julian – (pp. 22–23 and 23–25) was intercut with the Drew/April interaction (p. 23 and 25–26). Between the available script draft and the production draft, it seems to have been rewritten quite a bit – among other things injecting Jimmy (a kid Eirick/Julian is mentoring) as a third party in their conversation. Eirick/Julian drops the following truth-bomb on Dory: “I think you’ve decided that this matters to you because you have nothing else”, without her accepting his verdict, but instead being defensive.

The first part of the Drew/April interaction (p. 23) was dropped, not really changing anything.

The intercutting between the scene in the woods, and Dory’s discovery of Chantal in the bakery (pp. 26–29) seems to be drastically shortened.

There are also, of course, several changes in dialogue throughout, which mostly strengthens the juxtaposition. A few examples:

Portia’s reaction to the news of Chantal, and then suddenly wondering if she’s dated the waiter,

Gail’s question “Why does everything have to be so hard?” being changed to “How is it that you are so good at all the stuff no-one else wants to do?”, and

Drew – instead of saying “I love you” after sex – saying “My foot’s cramping”.

All these dialogue changes highlight Dory’s low status in different settings – in a very similar (but maybe not quite so harsh) manner to Walter White in the Breaking Bad-pilot.

What I learned

A lot of setup scenes have been cut throughout the episode, which indicates that the audience needs far less introduction and exposition than what feels necessary in the writing stage. Entire scenes about Dory were cut because they didn’t directly intersect with the Chantal-storyline – and likewise, smaller scenes were skipped when they didn’t add to the story (e.g. the liquor store and the yoga studio).

There is always room for more juxtaposition, more hard-hitting and confrontational lines, and more sadistic treatment of our characters. Watching the episode, it seems heightened from the script in several places – the disconnect between the characters and the meritless life of Dory. Even the removal of unnecessary exposition scenes could be argued to have a juxtaposing and heightening effect, as it removes the “connective tissue” allowing for more abrupt and crass dramatic shifts both within and between scenes.

All of this is written in a stream-of-consciousness, so I may have left out some things, or would have written it differently some other time. But I think there is a lot to learn from this type of analysis. I might do it again.

#teori#inspirasjon#humorproduksjon#search party#alia shawkat#john reynolds#john early#meredith hagner#brandon micheal hall#sarah-violet bliss#charles rogers#michael showalter

0 notes

Video

youtube

A theory describing why Dan Harmon thinks episode 304, Vindicators, is the worst Rick and Morty-episode of the series... Spoiler: It’s because it doesn’t follow the story formula. Which I haven’t described sufficiently here. Guess I have to put that in the queue.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

How to Make Memes

Sometimes, I stumble across a well-written article unexpectedly. This happened while browsing the blog of icons8, where they had an article called “How to Make Memes”. And it was a good intro with many examples.

It suggests getting inspiration from Reddit, and provides a separate article on viral content, before getting down to the details of meme-components. It discusses text in memes – both as subtitles and as “in-context elements”, and using text for clarity – and collages, cultural context, and trends.

The article has inspired me to research the topic further, but I think that’s for another, and more in-depth post. A good starting point may be the category-list at Know-Your-Meme, maybe this Daily Star-article describing 15 meme categories, and possibly Wikipedia. There are also scientific studies that can help explore the topic, such as this list, this article, this master thesis, another master thesis, this article on memes as political satire, this dissertation on the influence of memes, and probably lots of other resources. But this is a big topic, and not something I’m motivated to work on today.

0 notes

Video

youtube

This... this right here... this is satire GOLD! It actually took me several minutes before realizing the subtext, since I’m used to these bits being humourous at face-value without any layering of punchlines.

But this was a really good metaphor. Max Greenfield is so convincingly immersed in his own story, that it acts as a very effective “sleight of hand”. So once you realize what’s going on, you’re all “Oh... oh... Oh!!!”.

It’s a good example of how subverting expectations and slowly building up to a reveal makes the punchline stronger. It makes the satire sharper. It allows us to see the parallells more clearly, and provides a better foundation for the social commentary.

In this bit, Greenfield lays it out like this (at 6:10): “Maybe, if we were a little bit nicer to our referees – just a little bit – then more qualified people would want to be the referee.”

#satire#humorproduksjon#teori#late show#the late show#late show with stephen colbert#the late show with stephen colbert#stephen colbert#colbert#max greenfield#new girl

1 note

·

View note

Quote

We sort of make our money on volume. I don’t feel like, you know, I’d like to think «If we did the show once a week, I could craft this so that it was sterling». But truth of the matter is that I don’t think it would improve that drastically with consideration. We are the opposite of whiskey and fine wine. We’re more like Mad Dog 20/20. Just fucking drink it by the bus stop. You’ll get wasted. It’ll be fine.

Jon Stewart

27 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Jon Stewart on the process of producing the Daily Show:

“It’s actually easier for me to do this than when I used to do the regular talkshow, that I would do for like an hour, because we have a – like I say – a cycle to work off of. There’s a news cycle to work off of. You don’t necessarily have to adhere to it, but you at least get to work off it. So it’s somewhat easier... you known, like you said, it’s the contradiction, you’re tied to that news cycle, so in some ways it’s constricting, but it’s freeing because you don’t have to come in every day and go «what joke will I make about J-Lo’s dairyere (?) today?»”

4 notes

·

View notes

Quote

There is a part of me that feels like there is a high-mindedness to news and journalism that doesn’t exist. I feel like I do have liberties that you don’t have. And I could lose them by stepping into that, and what I would gain in that – I think – is a little bit more dignity, a little bit more – you know what I mean, like – I’d have a little more skin in the game, and I think there’s something about that that’s more courageous than what we do. Uhm, so that I very much admire… but I also think, though, that there is a part of me that says like ‘these rules have existed for people such as me forever, and we’re not the ones bending them’.

Jon Stewart on the difference between journalism and satire

17 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Best advice I ever received was probably from Jon Stewart. And Jon was like ‘Move towards your discomfort’ (…) In terms of subject matter. Like, if there’s something that’s making you uncomfortable, explore that. Like, dig into that.

Hasan Minaj, The Daily Show-correspondent

671 notes

·

View notes

Quote

I’m a climate scientist. I study weather patterns and climate. You’re talking about the *weather*, and maybe these networks are not meant to be viewed in aggregate – but there is an aggregate, there is an effect. And when people say ‘well, you’re influential too’ – I’m a 22 minute show, and when I say that, you know, puppets make crank calls in front of me, I don’t mean that to diminish comedy, I mean that that is not then reinforced through the next person. It’s not a relay. And there is an amplifying effect to the relay.

Jon Stewart on studying the political climate of 24 hour news networks

1 note

·

View note

Quote

Really, what we do on the show, it’s like political 'Chopped'. We take the ingredients of what we’re given that day. We gotta make sand castles out of it. And that’s all we’re trying to do. Respect the process, Kobe Bryant, Muse (?)… We’re just picking up marbles every day with our toes. Building a sand castle. It’s like ‘Fine. Get a little bit of Carly Fiorina, we got some Trump, mega vetting that we’re doing on the show tonight’… We build a sand castle. The water washes it away. We do it again. We do that, like, two hundred plus times a year. That’s what we’re supposed to do.

Hasan Minaj, The Daily Show-correspondent

12 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

American and British humor, part two.

1 note

·

View note

Video

youtube

Stephen Fry on the difference between American and British humor

1 note

·

View note

Quote

There’s something someone says, and then there’s the way they behave. And in between, in that arch, is where all the satire lives, you know – or the subversion. Those two, there’s a little arch in there… and the closer somebody is to the way they behave, the less fun they are to write jokes about.

Stephen Colbert on Face the Nation 25.12.2016

1 note

·

View note

Text

Pilot breakdowns

In the spirit of the Search Party pilot breakdown I wrote in August, I’ve written some notes on a few more pilots. I’ve kept it short, though.

One Mississippi (script)

The enjoyable interaction on page 2-3 in the pilot script has been cut in the pilot episode. Probably some practical reasons for this, but I would have fought to keep it.

The scene with the cab driver (pp. 11-13) is cut. This felt like a distraction and a break with the rhythm of the episode, so I think this was a good decision.

The contrasts between the characters produce a lot of humor: her girlfriend who’s happy and in her own bubble, and Tig who is much darker at heart. Her brother who is very practical and “simple”, and hear step father who is quite rigid and OCD. None of them are on the same wave length as Tig.

Insecure (script)

The first 3,5 pages were dropped in the pilot. We jump right into the classroom scene. A part of a skipped scene from page 3 is repositioned after the classroom scene. Then we get the mirror-rap, and then we get the Facebook message. So it is sort of unwrapped in an opposite order from the script.

In the restaurant scene, they split it so half the conversation is after they leave the restaurant, which makes it more visually interesting than staying in one place.

0 notes

Text

Historieutvikling: Contour-modellen

Jeg har gravd i arkivet mitt, og oppdaget et par interessante nedbrekk som kan være nyttige ressurser for kreativ skriving. Her er en nedskriving av Contour-modellen, basert på mobil-appen til Mariner Software som jeg lastet ned i 2011.

Jeg henviser også til åttesekvensmodellen, og Blake Snyder i denne artikkelen.

Contour-modellen starter med fire grunnleggende spørsmål, før den bryter disse videre inn i fire grunnleggende arketyper som igjen representerer de fire aktene i en filmfortelling. Særlig interessant er Ja/Nei-parene som dominerer andreakten (2A og 2B), som beveger oss nærmere og lengre vekk fra det sentrale spørsmålet.

Alt i alt en ganske interessant og annerledes tilnærming. Mer under...

4 SPØRSMÅL

Hvem er hovedpersonen? Protagonisten.

Hva prøver han/hun/de å oppnå? (re: goal) Profesjonelt (A-story), personlig (B-story) og privat (C-story). Hvordan vil deres seier vekke håp hos "resten av oss" og deres tap sette "oss andre" i fare?

Hvem prøver å stoppe ham/henne/dem? Hvem er antagonisten? Hvor villig er han/hun/de til å oppnå _sitt_ mål på bekostning av protagonisten? Hvis det ikke finnes en naturlig antagonist, må det etableres en sterk opposisjon/kontrast til heltens mål, noe som kontrasterer alt han kjemper for.

Hva skjer hvis de feiler? (re: stakes) Risikoen må handle om liv og død. I det minste en figurativ død eller noe som oppleves som en død av hovedpersonen (karakterdrap?).

4 ARKETYPER

Orphan i akt 1. Protagonisten er ensom eller iferd med å bli det. Det kan være utenfor hans kontroll eller han kan ha valgt en outsider-rolle selv ved å distansere seg fra familie eller kjærlighet på grunn av pliktfølelse, religion, egoisme eller sjenanse... for eksempel.

Wanderer i akt 2A. For å besvare Det sentrale spørsmålet må protagonisten ut på vandring. Han jakter på ledetråder, møter hjelpere så vel som motstandere, overkommer hindringer.

Warrior i akt 2B. Vis protagonisten kjempe for å besvare det sentrale spørsmålet. Krigeren forandres kun til sitt siste stadium gjennom en stor hendelse, vanligvis død eller gjenoppstandelse (?).

Martyr i akt 3. Protagonisten må være villig til å dø for å besvare spørsmålet. Han må være villig til å bli martyr. Viljen til å miste alt gjør at han kan vinne alt. Ved å gi opp det han ønsket, kan han få det han trenger (re: want vs. need).

FORMELEN

Når Protagonisten har/gjør/ønsker/får A, får/gjør/prøver/lærer han B, men oppdager at C skjer, noe som innebærer at han må respondere med D.

A = Orphan

B = Wanderer

C = Warrior

D = Martyr

AKT 1: Enstøing

Plot point 1: Introduser Protagonist, offeret/"Stakes character" eller Antagonist.

Plot point 2: Vis Protagonistens mangel i forhold til "Stakes character".

Plot point 3: Introduser Antagonist eller noe symbolsk for antagonisten.

Plot point 4: Vis "Deflector" som drar Protagonisten off-track.

Plot point 5: Katalysatoren. Protagonisten blir følelsesmessig involvert.

Plot point 6: Vis Protagonistens mål i forhold til "Stakes character"/love interest. Tydeliggjør Protagonistens problem.

Plot point 7: Protagonisten får (bevisst eller ubevisst) en alliert som tvinger ham ut av status quo.

Plot point 8: Vis hvordan Protagonisten er klar for å gå videre mot målet eller "Stakes character", men likevel ikke kan gjøre det.

Plot point 9: Vis at Protagonisten blir stoppet av en konflikt eller blir følelsesmessig truet av Antagonist eller "Deflector".

Plot point 10: Utdyp følelsene mellom Protagonist og "Stakes character" eller vis alvoret av trusselen mot ofrene.

Plot point 11: Vis "Deflector" eller Antagonist true med å ta "Stakes character" fra Protagonisten.

Plot point 12: Vis at Protagonisten bestemmer seg for at han MÅ handle for redde "Stakes character".

DET SENTRALE SPØRSMÅLET - Når dette er besvart med et definitivt "ja" eller "nei" er filmen over. Det kan være flere ledd, men må ha en klar "ja" eller "nei"-utforming for at problemstillingen kan bli løst.

AKT 2A: Vandrer

Denne akten består av sett med "ja" og "nei" som kaster Protagonisten nærmere og lengre fra det sentrale spørsmålet. De første tre "ja/nei"-parene, de neste to og deretter de siste to:

Ja/Nei 1-3: Protagonisten får hjelp fra allierte eller en mentorkarakter. Vi får se at Antagonisten ikke bare er slem, men VELDIG slem. Protagonisten lærer, nærmer seg det sentrale spørsmålet, men innser ikke at det han lærer egentlig er en avsporing. Protagonisten møter "low-level opposition", som han så vidt overkommer, som treningsøvelser for det som kommer. Kjærlighetshistorien/comic relief/sekundær-story starter.

Ja/Nei 4-5: Protagonisten fortsetter å vandre, lærer stadig mer om det sentrale spørsmålet og hva som trengs for å løse det. Han tester vannet med sine nyevunnede ferdigheter og verktøy. Motstanden øker og hindringene blir større. Antagonisten eller opposisjonen blir stadig mer bevisst på Protagonistens potensielle trussel og gjør motgrep.

Ja/Nei 6-7: Trusselen mot "Stakes character" øker til et liv/død-nivå. "Third act solution" blir vist, men betydningen av denne er ennå uviss for Protagonisten. En klar motsats til historiens theme blir uttrykt, det er denne ytringen eller situasjonen som debatteres videre i andre halvdel. Protagonisten er (eller føler seg) utlært, og er nødt til å konfrontere Antagonisten.

Antagonistens plan blir forklart til helten, av helten eller til andre.

Protagonisten kjemper mot Antagonisten eller entrer Antagonistens verden.

AKT 2B: Kriger

Ja/Nei 8-10: Protagonisten gjør teori til handling, tar beslutninger (både riktige og gale), og går aktivt inn for å besvare det sentrale spørsmålet. Han møter noe suksess, men deretter slår Antagonisten hardere tilbake. Det tematiske spørsmålet debatteres, gjerne i eksplisitt dialog mellom to karakterer. Helten vakler mellom disse synspunktene, mens han (uvitende?) forbereder sin største forandring.

AKT 3: Martyr

Big Yes: Protagonisten omfavner det positive tematiske argument, forplikter seg, etablerer løsningen på privat konflikt (intern, emosjonell story). ofrer seg for Stakes character. Dette etablerer løsning på B-story. Protagonisten handler så modig og dristig som mulig. Dette etablerer løsningen for A-plottet.

No: Til tross for høye ambisjoner, krasjer Protagonisten. Men han bretter opp ermene og går på.

Big No: Det sentrale spørsmålet er på nippet til å bli besvart i negativ retning. Vis helten (og eventuelt de allierte) gjøre et stort offer. Hent inn "Third act solution" som X-faktoren som gir Protagonisten en fordel.

Final Yes: Helten løser den private konflikten, noe som forløser den personlige konflikten (B-story), som igjen gir ham styrke/innsikt til å løse A-storyen. Jo tettere disse tre nivåene kan løses, jo bedre! Etterspillet samler trådene og viser protagonisten fullt aktualisert, returnert til sin vanlige verden hvor han aksepterer de positive verdier ved temaet. Klassisk Hollywood-ending.

Oppsummering

Så der har vi den modellen. I hovedtrekk sammenfaller jo mye med andre teorier (åttesekvensmodellen, BS2), men det er et par interessante ting å bite seg merke i:

Arketypene - Protagonistens reise og metamorfose. Hvordan han utvikler seg i løpet av historien, påvirket av sine omgivelser og dermed påvirkes også hans omgivelser i en sirkulær dialogisme mellom karakter og miljø.

Antagonisten - Hvis det ikke er et episk stykke, er det ofte at de antagonistiske kreftene faller ut. Men som det her påpekes kan de også være figurative. De kan komme fra innsiden, de kan komme som motsand fra miljøet. Men det må være en motsats til målet. Hva skjer "hvis ikke"?

Det sentrale spørsmålet - Filmen handler om et "skjer det?" som må kunne besvares enkelt... "skjer det?" for det er enkelt å ta stilling til, det er enkelt å heie på, det er enkelt å forstå... "Han skal redde henne. Klarer han det?".

Ja/Nei-parene - Apropos dialogisme. Andreakten skal ha en viktig vekselform... hver gang noe positivt skjer, kontrasteres dette med en motvekt. Tese-antitese... Blake Snyder har jo en tilsvarende løsning i sin modell med markering av +/- på hver beat, men Contour tydeliggjør dette forholdet bedre. Det som tydeliggjøres her (over Blakes modell) er at hele andre akt handler om det sentrale spørsmålet! Det er ikke noe rom for å spore av med masse sidehistorier - hver beat har en funksjon; å enten bringe oss nærmere eller lenger unna svaret på det sentrale spørsmålet.

Third Act Solution - Dette handler om frampek. Selv om third act solution er spesielt viktig, er det ikke nødvendig å stoppe der. Ta alltid en ekstra runde for å sjekke om det er andre frampek som kan bakes inn i en ytring eller et øyeblikk. Noe som peker mot alt som skal skje. Det binder narrativet og styrker koblingen mellom ulike handlingstråder. Og ved å la noe skje for så å grave det ned gjennom halve filmen, vil man fortsatt huske det og få en "Oh, snap!"-feel når det hentes opp igjen. Alle de beste bruker dette.

Positive og negative verdier ved den tematiske konflikten - Ingen andre modeller tar for seg akkurat dette. Debatten kommer ikke bare i forbindelse med om protagonisten skal forplikte seg til prosjektet, men også når han skal gå inn i den siste kampen. "Hva er det jeg kjemper for?", "Hvilke posisjoner eksisterer rundt dette temaet?", "Hva er min motivasjon, og er dette egoistisk eller selvoppofrende?". Veldig nyttig å tenke på. Skaper også et dypere og mer relaterbart narrativ; Publikum kan identifisere seg og minnes på å ta stilling til problemet før kampen fyrer løs.

Privat konflikt < Personlig konflikt < Hovedkonflikt - Måten de tre lagene av historien er nøstet sammen på er utrolig interessant. Den indre konflikten, den tematiske, løses først. Det tematiske forener Protagonisten med kjærlighetsobjektet/vennen/de allierte eller andre. Dette gir dermed enda større grunn til å kjempe og vinne den siste kampen. Veldig stilig.

Men: I forhold til andre modeller, er ikke tidslåsen fremhevet nok. Contour er sterk på de dype linjene i historien, men jeg syns fortsatt at Blake Snyders 5-point finale er uovertruffen. Åttesekvensen er uslåelig enkel og god for å ta en grovsortering. Jeg tror det kan være lurt å tenke slik:

Åttesekvensmodellen - Grovstrukturering av narrativet.

Blake Snyder's Beat Sheet (BS2) - Finstrukturering av narrativet.

Contour - Validering av narrativet. Sjekke at tematikken og trådene henger sammen og holder mål.

0 notes