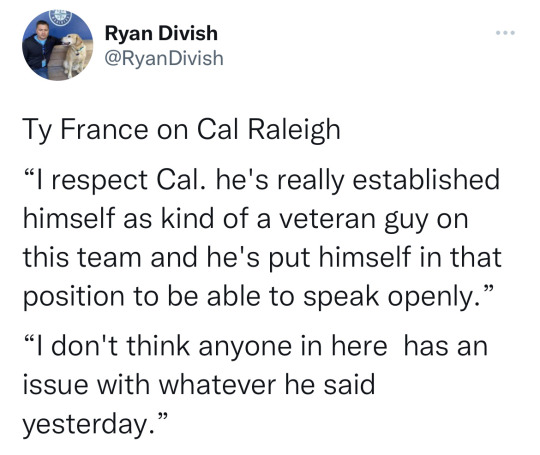

#i would die for cal raleigh and so would everyone on this team

Text

anyway everyone agrees with Cal bc he’s Right and he should say it

#i would die for cal raleigh and so would everyone on this team#mlb#seattle mariners#ty france#logan gilbert#jp crawford#cal raleigh

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Coronaviruas Delivery Die-Off Has Started

A single order awaits being carried out from Sushi Yasuda in Midtown Manhattan | Gary He

As dining rooms around the country shuttered in response to the pandemic, restaurants turned to delivery and takeout — but now, some chefs are saying it’s not worth it

“I don’t think we as a society are fully grasping how fucking dire and dystopian this can get,” says Andy Ricker, the chef and owner of the Pok Pok restaurant group. In the week following Oregon’s March 17 order to shutter dining rooms statewide to slow the spread of COVID-19, five of Ricker’s seven Portland-area restaurants continued operating in a takeout or delivery capacity. But after chef Floyd Cardoz’s March 25 death from complications of COVID-19, a loss that Ricker described on Instagram as “an arrow to the heart,” he decided to close all of his restaurants. “We are food professionals,” he wrote. “We’re okay following health code, and being careful about spreading foodborne illnesses. But a deadly coronavirus? That’s just not something we’re trained to deal with. It just hit me: It’s better to close than to be open.”

Ricker joins a growing number of chefs and restaurant owners across the country who initially tried to make a go of takeout and/or delivery after many cities implemented social distancing or shelter-in-place plans, but have recently decided it was too risky for the health and safety of their workers, and are instead choosing to close entirely. Last week, Chicago’s One Off Hospitality Group announced it was closing its restaurants (which include Big Star and the Publican) due to safety concerns for staff and customers; in Houston, Ford Fry announced he was shutting down his restaurants for similar reasons. This week, Los Angeles’s Sqirl added to the chorus, writing on Instagram that the restaurant’s last day of service will be April 3. At suburban Detroit’s Eli Tea, Elias Majid made the tough decision to close his shop thanks in part to “customers not respecting distance,” he tells Eater. “One lady came in visibly sweating and coughing.” From a financial perspective, Majid had been doing well, as had many of the restaurant owners interviewed for this story. But it’s public health they’re more concerned about now.

“The unfortunate reality is that there are no concrete guidelines available for small restaurants about how to operate in a way that’s not endangering their employees and potentially their customers,” says Heather Sperling, co-owner of Botanica in Los Angeles. When the city’s “safer-at-home” orders came down on March 19, Sperling and her partner, Emily Fiffer, quickly rejiggered their restaurant setup into a marketplace, selling pantry items, fresh produce, and prepared foods.

Business was “hugely successful,” Sperling says, and the revenue sustainable enough to allow Botanica to stay open indefinitely. And yet, on March 20, she and Fiffer announced on Instagram that they were closing to “regroup, restock & do a precautionary quarantine.” Ultimately, “until we better understand how to operate in a way that truly feels safe — if that’s even possible — we didn’t feel it was fair to put our employees at risk,” Sperling says.

In other parts of the country, other operators echoed that sentiment. On March 25, the team at Jonathan Waxman’s beloved New York City restaurant Barbuto announced they were halting their popular to-go operation and closing entirely. “We have been so thrilled to have your support, however the crisis has become too hard to justify our staying open. ... Until the government declares New York City safe, we will remain hunkered down for the duration,” they wrote. Other restaurants across the city, including Superiority Burger and Cafe Katja, posted similar messages of their own.

Back in Portland, Ricker’s post hit home for Johnny Nunn, the owner of Verdigris. Although the French-inspired restaurant had been doing a robust curbside takeout business, Nunn decided to close down on March 25. “I just feel outmatched,” he explains. “I’m a cook. I’m not qualified to make decisions about people’s wellbeing in the face of a crisis.”

Some chefs and owners say that part of the issue is the lack of guidance about worker safety from local and federal officials, who are themselves scrambling to manage and distribute information to an industry in crisis. Nick Cho, the owner of San Francisco’s Wrecking Ball Coffee Roasters, has written Medium posts about the measures he’s put in place to keep his workers safe: They include trying to minimize all contact by moving service to the front door, installing an enormous plexiglass sneeze guard that separates customers from baristas, and asking all customers to wrap their fingers in a sheet of thin wax paper before signing on a touch screen for their credit card orders. Momofuku owner David Chang has also been particularly vocal on this topic: As part of a long Twitter thread on the question of how to keep workers safe in the event that restaurants reopen, he wrote, “One thing is for certain we cannot wait for local, state or federal authorities to prepare us. We need to go on the offensive here.”

“What I wish is that there would be rapid training and mobilization within the Health Department, to send a free consultant to any operation that wants to stay open at all, to come into their facility and help establish best practices,” Sperling says. “Instead, what we got was an email alerting us to the safer-at-home ordinance that had been passed four days earlier. It was laughably, dismayingly useless.”

When I reached out to the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health to ask if it had any specific guidelines for restaurants to operate safely in a takeout or delivery capacity, it sent over this link, which encourages increased handwashing, basic food safety precautions, and the establishment of “social distancing practices for those patrons in the queue when ordering or during pick-up.” It declined to comment further.

Other officials are trying to address an issue of unprecedented scale, while grappling with quickly changing and sometimes-conflicting information about the virus and best practices for preventing it. In Oregon’s Multnomah County, where Portland is located, environmental health supervisor Jeff Martin says his team has been calling every restaurant in their district individually, talking to them about how to safely execute delivery and takeout and answering as many questions as possible—often, he says, about proper sanitation procedures and what exactly “contactless” delivery means. “We’re doing phone calls, video inspections, and email—we’re trying to use technology to cover as much ground as possible,” he says. The Multnomah County Health Department has set up an online FAQ page that’s updated constantly with questions like “Should I wear a mask when preparing food?” (“No, masks should only be worn for people experiencing symptoms. If you are experiencing symptoms, you should not be at work.”) and “What are acceptable takeout and grab-and-go methods?” (Maintain social distance, no self-service, etc.)

And on a personal level, Martin adds that he still feels comfortable ordering takeout. “I think it’s still safe,” he says. “I’ve been picking up food almost every day.”

Gary He

Carbone in Manhattan resorted to taping out spaces for waiting couriers to maintain distance

Not everyone is discouraged by the efforts of their local officials. In Raleigh, North Carolina, chef Ashley Christensen has been working closely with the Wake County Health Department to stay ahead of rapidly changing developments: On March 17, the state ordered all bars and restaurants closed for dine-in; on March 27, Wake County issued shelter-in-place orders. “We’ve been in constant contact with the governor and county reps; any time any document is produced, we have direct access to it, and we distribute it to a number of colleagues,” Christensen says. “These guys are busy, they have a lot on their plates right now.”

Christensen started offering takeout at her restaurants two weeks ago, but found herself dealing with an unforeseen problem: the crowds who clamored outside without adhering to social-distancing guidelines. It’s an issue that has dogged restaurants around the country, and created perhaps the biggest threat to takeout safety. This became startlingly clear the week before last at the New York City restaurant Carbone, where the crowds of delivery workers and pickup customers were so bad that the police had to be called and the restaurant’s managers eventually closed down the operation, leaving a number of customers empty-handed.

“We can’t really control how the public thinks and how they interact with each other in front of our shops,” Christensen says. So she and her business partner and wife, Kaitlyn Goalen, quickly made the decision to pivot to a delivery-only model, offering premade dinner kits prepared in a commissary kitchen with social-distancing practices in place.

“I don’t think anyone who is staying open is really thinking they’ll make money — most of them are scared that if they close, they’ll lose everything.”

The pair aren’t sure what they’ll do in a few days when they run out of the product they had already ordered, and which had made the switch to delivery temporarily possible. “Takeout and delivery was important for us to do for a week to stretch the timeline of what we could do for the team we’ve been able to retain, and hopefully stretch the cash flow until we can access some other kind of support,” says Goalen. “But the biggest concern here is the very real reality that people are getting sick and dying.”

All of the chefs interviewed for this story have been in constant communication with their staff about whether they felt comfortable coming to work. “I checked in with every person on my team, and they all said, as bad and hard as this is, I feel safer not working,” says Sylvie Gabriele, owner of Love & Salt in Manhattan Beach, California. After initially pivoting to become a curbside and delivery grocery popup, Gabriele decided to close on March 26. “I wanted to ride as far as we could until some relief came through, so there could be a little good news,” Gabriele says. “I’m just hoping I didn’t wait too long.” The day after she closed the restaurant, the House of Representatives passed a $2 trillion economic stimulus plan, which will offer some relief to affected workers in the restaurant industry — though it still might not be enough for small-business owners and millions of workers.

Some owners who are frustrated by the lack of guidance from official sources are still choosing to stay open, and implementing extraordinary safety precautions as best they can. In San Francisco, which ordered restaurants and bars to close for dine-in service and residents to shelter in place on March 17, Wrecking Ball owner Nick Cho says that safety means “taking control of our space and the customer environment.” Of the measures he’s taken to that end, he explains, “I’m just trying to think about it in terms of managing systems and creating protocols and procedures. Too much is being left to individuals to figure this out on our own.”

Most chefs emphasize with their colleagues who choose to stay open. “I can’t find fault with it — I myself was there just a few days ago,” says Ricker. “I wanted to protect as many employees’ job status as I could, and I wanted to show spirit and feed the community. I don’t think anyone who is staying open is really thinking they’ll make money — most of them are scared that if they close, they’ll lose everything.”

He hopes that as the situation continues to evolve, the government will “do the right thing” and provide relief so that more operators feel comfortable shutting their doors. “I love my restaurants, and I love the restaurant world, but we are not a part of the supply chain that can deliver basic human necessities to stay alive in hardship,” Ricker says. “We have got to stay home. All of us.”

Jamie Feldmar is a Los Angeles-based writer and cookbook author. See more at jamiefeldmar.com and follow her @jfeldmar.

Photos by Gary He

from Eater - All https://ift.tt/2Juq9Ej

https://ift.tt/2QZaBws

A single order awaits being carried out from Sushi Yasuda in Midtown Manhattan | Gary He

As dining rooms around the country shuttered in response to the pandemic, restaurants turned to delivery and takeout — but now, some chefs are saying it’s not worth it

“I don’t think we as a society are fully grasping how fucking dire and dystopian this can get,” says Andy Ricker, the chef and owner of the Pok Pok restaurant group. In the week following Oregon’s March 17 order to shutter dining rooms statewide to slow the spread of COVID-19, five of Ricker’s seven Portland-area restaurants continued operating in a takeout or delivery capacity. But after chef Floyd Cardoz’s March 25 death from complications of COVID-19, a loss that Ricker described on Instagram as “an arrow to the heart,” he decided to close all of his restaurants. “We are food professionals,” he wrote. “We’re okay following health code, and being careful about spreading foodborne illnesses. But a deadly coronavirus? That’s just not something we’re trained to deal with. It just hit me: It’s better to close than to be open.”

Ricker joins a growing number of chefs and restaurant owners across the country who initially tried to make a go of takeout and/or delivery after many cities implemented social distancing or shelter-in-place plans, but have recently decided it was too risky for the health and safety of their workers, and are instead choosing to close entirely. Last week, Chicago’s One Off Hospitality Group announced it was closing its restaurants (which include Big Star and the Publican) due to safety concerns for staff and customers; in Houston, Ford Fry announced he was shutting down his restaurants for similar reasons. This week, Los Angeles’s Sqirl added to the chorus, writing on Instagram that the restaurant’s last day of service will be April 3. At suburban Detroit’s Eli Tea, Elias Majid made the tough decision to close his shop thanks in part to “customers not respecting distance,” he tells Eater. “One lady came in visibly sweating and coughing.” From a financial perspective, Majid had been doing well, as had many of the restaurant owners interviewed for this story. But it’s public health they’re more concerned about now.

“The unfortunate reality is that there are no concrete guidelines available for small restaurants about how to operate in a way that’s not endangering their employees and potentially their customers,” says Heather Sperling, co-owner of Botanica in Los Angeles. When the city’s “safer-at-home” orders came down on March 19, Sperling and her partner, Emily Fiffer, quickly rejiggered their restaurant setup into a marketplace, selling pantry items, fresh produce, and prepared foods.

Business was “hugely successful,” Sperling says, and the revenue sustainable enough to allow Botanica to stay open indefinitely. And yet, on March 20, she and Fiffer announced on Instagram that they were closing to “regroup, restock & do a precautionary quarantine.” Ultimately, “until we better understand how to operate in a way that truly feels safe — if that’s even possible — we didn’t feel it was fair to put our employees at risk,” Sperling says.

In other parts of the country, other operators echoed that sentiment. On March 25, the team at Jonathan Waxman’s beloved New York City restaurant Barbuto announced they were halting their popular to-go operation and closing entirely. “We have been so thrilled to have your support, however the crisis has become too hard to justify our staying open. ... Until the government declares New York City safe, we will remain hunkered down for the duration,” they wrote. Other restaurants across the city, including Superiority Burger and Cafe Katja, posted similar messages of their own.

Back in Portland, Ricker’s post hit home for Johnny Nunn, the owner of Verdigris. Although the French-inspired restaurant had been doing a robust curbside takeout business, Nunn decided to close down on March 25. “I just feel outmatched,” he explains. “I’m a cook. I’m not qualified to make decisions about people’s wellbeing in the face of a crisis.”

Some chefs and owners say that part of the issue is the lack of guidance about worker safety from local and federal officials, who are themselves scrambling to manage and distribute information to an industry in crisis. Nick Cho, the owner of San Francisco’s Wrecking Ball Coffee Roasters, has written Medium posts about the measures he’s put in place to keep his workers safe: They include trying to minimize all contact by moving service to the front door, installing an enormous plexiglass sneeze guard that separates customers from baristas, and asking all customers to wrap their fingers in a sheet of thin wax paper before signing on a touch screen for their credit card orders. Momofuku owner David Chang has also been particularly vocal on this topic: As part of a long Twitter thread on the question of how to keep workers safe in the event that restaurants reopen, he wrote, “One thing is for certain we cannot wait for local, state or federal authorities to prepare us. We need to go on the offensive here.”

“What I wish is that there would be rapid training and mobilization within the Health Department, to send a free consultant to any operation that wants to stay open at all, to come into their facility and help establish best practices,” Sperling says. “Instead, what we got was an email alerting us to the safer-at-home ordinance that had been passed four days earlier. It was laughably, dismayingly useless.”

When I reached out to the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health to ask if it had any specific guidelines for restaurants to operate safely in a takeout or delivery capacity, it sent over this link, which encourages increased handwashing, basic food safety precautions, and the establishment of “social distancing practices for those patrons in the queue when ordering or during pick-up.” It declined to comment further.

Other officials are trying to address an issue of unprecedented scale, while grappling with quickly changing and sometimes-conflicting information about the virus and best practices for preventing it. In Oregon’s Multnomah County, where Portland is located, environmental health supervisor Jeff Martin says his team has been calling every restaurant in their district individually, talking to them about how to safely execute delivery and takeout and answering as many questions as possible—often, he says, about proper sanitation procedures and what exactly “contactless” delivery means. “We’re doing phone calls, video inspections, and email—we’re trying to use technology to cover as much ground as possible,” he says. The Multnomah County Health Department has set up an online FAQ page that’s updated constantly with questions like “Should I wear a mask when preparing food?” (“No, masks should only be worn for people experiencing symptoms. If you are experiencing symptoms, you should not be at work.”) and “What are acceptable takeout and grab-and-go methods?” (Maintain social distance, no self-service, etc.)

And on a personal level, Martin adds that he still feels comfortable ordering takeout. “I think it’s still safe,” he says. “I’ve been picking up food almost every day.”

Gary He

Carbone in Manhattan resorted to taping out spaces for waiting couriers to maintain distance

Not everyone is discouraged by the efforts of their local officials. In Raleigh, North Carolina, chef Ashley Christensen has been working closely with the Wake County Health Department to stay ahead of rapidly changing developments: On March 17, the state ordered all bars and restaurants closed for dine-in; on March 27, Wake County issued shelter-in-place orders. “We’ve been in constant contact with the governor and county reps; any time any document is produced, we have direct access to it, and we distribute it to a number of colleagues,” Christensen says. “These guys are busy, they have a lot on their plates right now.”

Christensen started offering takeout at her restaurants two weeks ago, but found herself dealing with an unforeseen problem: the crowds who clamored outside without adhering to social-distancing guidelines. It’s an issue that has dogged restaurants around the country, and created perhaps the biggest threat to takeout safety. This became startlingly clear the week before last at the New York City restaurant Carbone, where the crowds of delivery workers and pickup customers were so bad that the police had to be called and the restaurant’s managers eventually closed down the operation, leaving a number of customers empty-handed.

“We can’t really control how the public thinks and how they interact with each other in front of our shops,” Christensen says. So she and her business partner and wife, Kaitlyn Goalen, quickly made the decision to pivot to a delivery-only model, offering premade dinner kits prepared in a commissary kitchen with social-distancing practices in place.

“I don’t think anyone who is staying open is really thinking they’ll make money — most of them are scared that if they close, they’ll lose everything.”

The pair aren’t sure what they’ll do in a few days when they run out of the product they had already ordered, and which had made the switch to delivery temporarily possible. “Takeout and delivery was important for us to do for a week to stretch the timeline of what we could do for the team we’ve been able to retain, and hopefully stretch the cash flow until we can access some other kind of support,” says Goalen. “But the biggest concern here is the very real reality that people are getting sick and dying.”

All of the chefs interviewed for this story have been in constant communication with their staff about whether they felt comfortable coming to work. “I checked in with every person on my team, and they all said, as bad and hard as this is, I feel safer not working,” says Sylvie Gabriele, owner of Love & Salt in Manhattan Beach, California. After initially pivoting to become a curbside and delivery grocery popup, Gabriele decided to close on March 26. “I wanted to ride as far as we could until some relief came through, so there could be a little good news,” Gabriele says. “I’m just hoping I didn’t wait too long.” The day after she closed the restaurant, the House of Representatives passed a $2 trillion economic stimulus plan, which will offer some relief to affected workers in the restaurant industry — though it still might not be enough for small-business owners and millions of workers.

Some owners who are frustrated by the lack of guidance from official sources are still choosing to stay open, and implementing extraordinary safety precautions as best they can. In San Francisco, which ordered restaurants and bars to close for dine-in service and residents to shelter in place on March 17, Wrecking Ball owner Nick Cho says that safety means “taking control of our space and the customer environment.” Of the measures he’s taken to that end, he explains, “I’m just trying to think about it in terms of managing systems and creating protocols and procedures. Too much is being left to individuals to figure this out on our own.”

Most chefs emphasize with their colleagues who choose to stay open. “I can’t find fault with it — I myself was there just a few days ago,” says Ricker. “I wanted to protect as many employees’ job status as I could, and I wanted to show spirit and feed the community. I don’t think anyone who is staying open is really thinking they’ll make money — most of them are scared that if they close, they’ll lose everything.”

He hopes that as the situation continues to evolve, the government will “do the right thing” and provide relief so that more operators feel comfortable shutting their doors. “I love my restaurants, and I love the restaurant world, but we are not a part of the supply chain that can deliver basic human necessities to stay alive in hardship,” Ricker says. “We have got to stay home. All of us.”

Jamie Feldmar is a Los Angeles-based writer and cookbook author. See more at jamiefeldmar.com and follow her @jfeldmar.

Photos by Gary He

from Eater - All https://ift.tt/2Juq9Ej

via Blogger https://ift.tt/3aD6wWz

0 notes