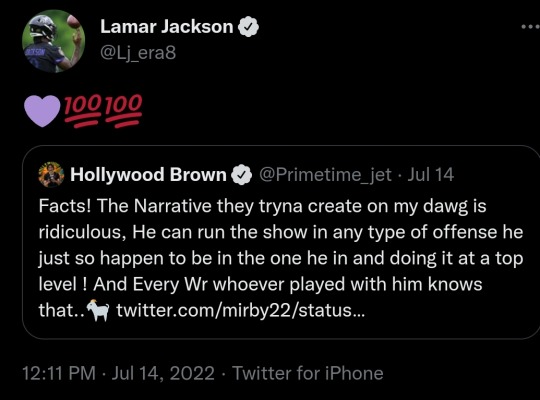

#in MY personal interpretation of this narrative.. hollywood being not so subtle with his love for lamar

Text

True love: winning

Skip bayless: exists

#sorry but all i can focus on is 'his man' 🥰🥰#like yeah thats hollywoods man#AND DONT FORGET IT!#kyler cant cover the big picture without the camera needing to tilt down#lamars purple heart 😭😭#them still bein close even after a trade.. where have i heard this before 🤔#holly rlly wrote him a paragraph of praise and lamar replied with the 100 emoji 💀..#2 of them!!#hollywood defends his man 😊😊🥰🥰..#sorry im still stuck on that let me analysize what i spelled that wrong whatever eat my farts#in MY personal interpretation of this narrative.. hollywood being not so subtle with his love for lamar#and constantly pushing the blame on the system which makes sense but also he hates himself lol#but he also also hates himself enough to not let lamar know he hates himself#he wants to distance himself from lamar for the best of lamar but also he just cant seem to make himself let go#every excuse just seems to hurt lamar more and more#until hollywoods worried lamar actually hates him and thinks him a traitor...#for being cold..#and hes worried lamar will start to hate himself too which isnt ok when actually good people do that 2 themselves in his opinion#'yet what hes saying sounds hypocritical' it's because hes in LOVE#str8 people wish they could be as insane (pos nonquirky) as us. they can only be insane neg and they Know it#hollywood complaining abt the narrative... bby you literally helped contribute to that#my contradictarion... he is Sick#hollywood/jackson#their relationship is so hard to explain to me but i love it and i hate it it's so fun to me i despise it#im having the time of my life#im in constant misery#i hate you skip

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Part 2

This is part 1.

Can you tell how tired I was getting by the end? This is life under meds, but given the other benefits (I think?), I’ll take it for now.

When I woke up the next morning, I had a whole lot I was thinking about and it’s stuff I want to say given I said a lot, but didn’t cover this stuff. I’m still happy with part 1, I think that’s just how I write, moving from subject to subject more or less organically and it does show me to more unstructured even if there is a vague plan for how I want the piece to go.

Anyway let’s get going.

As always, mild spoilers for well, everything. If you haven’t seen this stuff and are mildly interested in watching them then ah, you may have a lot of catching up to do. I don’t think I’ll drop any real hard spoilers for anything but you never know.

Ghost In The Shell is an Outsider story

There are whole stacks of lore you could dive into with Stand Alone Complex in particular, with Motoko having been in an aircraft accident and getting her first shell (cyber-body) at a very early age, what that means, the thing with Kuze (avoiding spoilers here), and the extended cast - not that Paz, Boma and even Ishikawa get a whole lot of time anyway - but it’s not really that important.

Looking at just Mamoru Oshii’s 1995 film, and even more-so his 2004 film Innocence (not really a sequel but usually regarded as such), the narratives cast the characters very much as Outsiders. In the first film, Section 9 is already at odds with the government in general and while it’s subtle, Aramaki as a department head is certainly different from his contemporaries, even if we don’t see much of it - again, so much more of this in Stand Alone Complex. Motoko’s early conversation with Togusa in the first film is probably the most telling as far as playing it loud. She speaks in pragmatic terms to why he’s there, but this is a precursor to what will ultimately transpire for herself at the conclusion of the film, something very intentionally written into the film. Batou is also an Outsider in more ways than one, not only in the role he plays in the department but in the very clear personal boundary between him and Motoko. There are boundaries between Batou and everyone and they become more apparent in the second film. Togusa is easy pickings so I’ll leave him alone, suffice to say if the film needs one, he’s the audience’s window of ignorance which is why he’s discarded so willingly half way in. He gets his time in the spotlight in Stand Alone Complex and it’s pretty amazing.

As for Motoko... I admit it is difficult separating my understanding of her character from Stand Alone Complex and attempting to just isolate what’s shown of her in the first film but I’ll try.

I mentioned the film’s centrepiece montage in my previous journal, in which we might say Motoko is the centrepiece but if so, she probably shares it with the city itself, and I feel much more is being said about the two together rather than separated simultaneously. This would be one of the first indications of Motoko’s sense of identity, of otherness, isolation, questioning. Again the scene that plays it most loud would be diving on the boat and her speech to Batou. There are other moments tho; single frames of her face, looks, movements that are lingered on, I feel like Oshii is constantly telling us about her and what she’s going to do, but more important than that, why she’s going to do it and how she feels.

Ghost in the Shell is a film about great emotion, and not like I’d know because it’s been a long time since I’ve looked into the discourse around it, but I suspect no-one really talks about it as a film about feelings.

I realise these days I talk more and more about moods and art being mood pieces. I labelled my Instagram account as being “A catalogue of moods” and I’m very fond of the use of the word in vernacular. It might seem flippant but it’s immensely empowered, especially for me as an individual when I understand my moods and can translate them into, via and thru art. I do appreciate many struggle with Oshii’s cinematic language as it can appear cold and detached and that’s fine, but it’s anything but for me - it’s immensely emotionally charged, it just appears differently to what audiences are perhaps accustomed to seeing. It’s a different language that perhaps takes time to learn, but it’s all there.

This couldn’t become more evident than in Innocence (the Ghost in the Shell 2 moniker I think was a western addendum). Batou takes centre stage and is immediately presented as bluntly as possible as an Outsider, reaffirmed later by Aramaki who also cements Togusa’s position in limbo.

I should pause and say that within the GitS canon, I feel Togusa is definitely embraced by Section 9, so he’s not wholly an Outsider to the department, but for obvious reasons, he doesn’t fully share all of their daily or philosophical concerns - hence not wholly. He would also definitely be an Outsider to most other members of the force after joining Section 9, but unfortunately I’m not here to love Togusa, poor guy - I feel like he’s always a bit unloved. Someone write a giant essay in service to his greatness. He actually is great.

But I adore Batou in Innocence. I love his story, his struggle, his emotion. I love how present Motoko is without ever appearing on screen and then when she does, the impact she has on everything, especially with the lines she delivers, one of which I quoted to open the last journal. Batou is in many ways a shadow of what Motoko was and is/has become, just in physical form, mirroring her in a real world manifestation with the natural physical limitations that comes with.

For some reason I feel like I need to inject a comment about Batou putting the jacket/vest on Motoko’s body. I don’t know if people perceive this as an act of masculine modesty but it’s not how I read it. I did stumble on this action for years but as I began to interpret the films as Outsider stories, I realised that he does this as an act of inclusion, and that Motoko consents, permits him to and doesn’t immediately react with violence or technological recourse we know she is well capable of, indicates it’s mutual. Their inclusion isn’t just about the boundaries of the Section 9 department but extends beyond that, an inner circle that may only contain the two of them - inside which there are still boundaries between them Batou can never cross. Those boundaries become infinitely more apparent after the final events of the first film, and the second film effectively is all about how he feels about them. He is an ultimate Outsider, but so is Motoko in the state she now is in.

Section 9 is a department of stray dogs. Individuals who haven’t quite fit in where they belong, and found belonging with one another. Then, after a time, one of them moves on - at the conclusion of the first film, and then another feels an almost permanent and ultimate sense of separation - more or less the duration of the second film.

Ghost in the Shell isn’t about technology and sentience and hacking and corporations at all. It’s about loneliness and belonging and acceptance and affection. It’s about how that feels.

I’m Not Sure Why People Struggle With David Lynch Films

I need to stop talking about anime.

Honestly I looked at the list at the start of the last journal and thought hell yea Sky Crawlers, Jin-Roh, Haibane Renmei and Lain let’s unpack some shit! but honestly I’ll run out of time and I should really draw from a variety of mediums and sources.

OK I’m not being facetious when I say Lynch’s films are fairly straight-forward narrative-wise. Again, it’s hard for me to position myself in a place where I’m not into the stuff I’m into and maybe that’s what gives me the cinematic language familiarity to parse them but that just sounds like wanker bullshit to me. I don’t mind if folks don’t like Lynch films, that’s fine. But they aren’t difficult.

So in the context of everything else, even on that short list on the last journal, plus how I keep trying to shift the discussion of works from the pragmatic reading of them to an emotional reading of them from a mood perspective, I feel as tho the same process can be applied to Lynch. So much about his films are about how they make you feel, or I’ll say - how they make *me* feel. It might be grandiose to assume I’m feeling the correct emotion, that these are the moods that David Lynch himself is attempting to create and evoke and thus, I am interpreting them correctly but hey - I enjoy the hell out of the films, feel I understand them and watch them over and over again so that’s all I’m basing it on.

That’s not to say there are things I dismiss as meaningless or that I don’t understand in his films, it’s just that I don’t have to parse them immediately at first watch and perhaps that’s the audience’s problem. I don’t know if reverse-diagnosis is appropriate but looking at how much hand-holding there is in other directors’ films might be just as telling. I mean I saw Nolan’s Tenet and was about the least confusing thing I’d ever seen in my life but apparently *that* confused people, and you know hey that’s fair I guess, but I mean Nolan did a whooooole lot of audience hand-holding in that film, I mean, the dialogue was terrible. There was so much unnecessary exposition, which I generally find in all of his films, so if an audience can’t follow that then OK sure, Lynch is going to be a problem.

The thing is popcorn cinema is totally OK. I watch it. I really love it, I’ve written about it before, it’s good Industry. There’s a lot of great creativity in popular cinema, I don’t at all think poorly of it and I love seeing a really well produced, Hollywood picture... but I guess if that’s all you consume, and I guess if folks’ short-format episodic media (aka series - think Netflix, HVO etc.) is more or less to the same standard, then it begins to make sense that anything outside of that isn’t going to make sense.

Long story short - Lynch films tell simple stories where the feeling of the film is as important as the narrative of the film. To understand the story, you have to understand the feeling, and vice-versa.

Surprise surprise, it turns out independent and deemed “fringe” film-makers... aka Outsiders... make films about Outsiders.

Now I wouldn’t know if any of the Marvel films thematically are about Outsiders or Outsider culture, they probably are and very loudly at that, but the reason I’ve never included one in my catalogue of moods is they all read the same way. Not only are Marvel films mostly indistinct from one other to me, they’re also mostly indistinct from much of popular culture in general. That doesn’t make them bad, some of them still have some pretty awesome stunts, visfx, even parts of the narratives, funny jokes etc. in them, but on the whole they’re not useful to me as things I deem truly valuable in the long-term.

It’s OK, I’m not at all going to lament the proliferation of Marvel films, a lot of them have been pretty cool and they keep people in work. Meow meow meow “the death of cinema” mate, sure - I find it more difficult to find the sorts of films I like but that’s always been the case. Humans will do what they do, it’s not a read on cinema, it’s about being an Outsider and what that’s all about. True, maybe weird shit like Lynch and Noe might be more difficult to make, but the weird-indie corner was also dominated by white men and that needs to change, so who knows what the future holds.

Can you detect the point at which I took my meds and started getting tired?

Ghost in the Shell // Innocence // What We Want // What We’re Left With

Growing up as an Outsider, I feel as tho the first Ghost in the Shell film carries the weight of isolation, questions of identity and belonging, ultimately of acceptance, empowerment and liberation. Then Innocence brings to bear very similar moods but states that things may not necessarily change for the better, they simply change state. I love that in both narratives, the main texts of hacking or corrupt corporations, crime etc. are the least common denominators and barely relevant to heart of the films. I think about the theme of icons in Innocence, icons operatively being the dolls throughout the film, and the final image of Togusa’s daughter’s gift. As humans we assume we’re to take the position of biological humanity as representative of sentience, taking moral priority over all other beings. Earlier in the film we think Togusa is in limbo, but at the conclusion Motoko asks the question, or perhaps states that perhaps we’re all in limbo together.

I think that’s a significant part of what growing up as and being an Outsider is like, what it feels like. Christians have this saying about “living in the world but not of the world” (derived from a bible verse) and honestly I don’t think they know what it means because they just operate like a cult, but I think queers and folks with long term mental health conditions have a better idea. We are pushed out to the fringes of our social groups from an early age, long before we know or understand what’s different about us. Our peers and the adults around us do this to us because their social behaviours are so well hard-coded, even they may not even know precisely what’s different about us, they just do - and they’re right. We are different. And they don’t accept us.

Maybe I am starting to get a little more upset that weird/different art is becoming more difficult to fund and make, because it’s for us, for me. It speaks to me. You already have so much, and representation and inclusion is so important. I don’t just need queer cinema, I need weird cinema, I need moods. I need quiet, introspective, pensive, reflective, Outsider moods.

I still feel like an Outsider. I have a few people who understand more about me, but I don’t think I have a place, not in a real sense. I have never felt that. Art is one of the few places I feel any connection with anything, and connecting with people is a very odd thing to consider - honestly, I actually would really like to connect with people but the unique combination of being queer *and* autistic comorbid with bipolar makes it really tough, more difficult the older I get. And now all you want to do is fund Marvel movies. I can’t feed off of that.

I’m getting tired, I’m not making any sense.

It’s time for bed.

#2021#chrono#ghost in the shell#innocence ghost in the shell#outsider culture#outsider#queer#queer culture

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Review:The Secret Theatre by Anders Lustgarten

So last year I saw TST at the Sam Wanamaker Theatre and I found my review for it just now. (Below cut).

The Secret Theatre by Anders Lustgarten

As a second year student with deadlines ominously marching over the horizon, Sir Francis Walsingham’s vast swathes of paper (his filing cabinets are ingeniously built into the set itself) hit a little close to home. The Secret Theatre is about more than one man’s exploding in-tray, however.

Anders Lustgarten’s play is allegory first, tragedy second, with an ending to match. If you prefer your allegory subtle and implied, this is not the play for you. Lustgarten is as subtle as a shoe to the face. This isn’t necessarily a problem, as much of the allegory already speaks for itself: spies, asylum seekers, martyrs, beheadings, zealots, propaganda, mass murder- all of these things are inherent to the historical source material. Parallels are therefore easily established. Nevertheless, there are moments when characters feel more like mouthpieces for the playwright than people with their own thoughts. Sir William Cecil’s line “If you tax the bankers, they’ll leave” is probably the biggest example of this, being a modern soundbyte word for word.

The strength of this play lies not in the messages of its allegory. The arguments that torture doesn’t elicit proper information, that martyrdom inspires recruitment to the cause, that unscrupulous politicians take advantage of fears over immigration, that surveillance spreads fear and mistrust, are old and surprisingly safe. The strength of this play lies more in its characters coming to such realisations. The look on Walsingham’s face, when a Catholic torture victim triumphantly declares how martyrdom boosts militant Catholicism, is far more powerful than the line itself.

A sense of relentlessness and hopelessness pervades this play, in keeping with Lustgarten’s overarching theme: that authoritarianism poisons everything it touches. The setting is highly evocative: the play’s first and current run (until 16 December) is at the beautiful Sam Wanamaker Theatre. The auditorium is small and compact and the thrust stage therefore makes the action very intimate. All of the lighting onstage is done with candles, lit and doused throughout the play, so the symbolism of “working in the shadows” is made very clear (at one point, Queen Elizabeth’s massive skirt swept across a candle flame and there was a collective intake of breath from the audience). The gilded panelling and painted ceiling of the theatre are alone worth a visit to the theatre and juxtapose excellently the beauty of Elizabethan culture with the ugliness of the play’s violent politics. There is something particularly haunting about the sight of a noose when it’s swinging from a ceiling painted with cherubs. The use of tiny paper models to represent the Armada and the city of London is inspired as it is highly symbolic of the main characters’ power, as they tower over society, but also the distorting effect of paranoia upon reality.

The cast give excellent performances. Aidan McArdle as Walsingham has to convey a huge range of passionate emotion as well as master the moments of dry and quiet humour that encapsulate the character’s shrewd and cynical observations. The only hitch in his otherwise entirely believable performance is that in Act One he moves around the stage with the vim and vigour of someone who doesn’t have so much as the common cold, let alone debilitating and untreated health conditions, random bursts of coughing aside. This hitch is gone in the second act, when the disintegration of Walsingham’s physical and psychological health is visceral and harrowing.

In the hands of an actor of lesser skill, the role of Queen Elizabeth I in this play could easily become one-dimensionally catty, but Tara Fitzgerald keeps the character as venomous as she is despairing. Tara Fitzgerald is aided by the fact that, refreshingly, the production refuses to follow Hollywood’s recent lead in sexing up history: Elizabeth’s dresses are magnificent, but the wig and white face paint are there to be authentic, not to aesthetically appeal to the viewer. All of the play’s violence serves a narrative and thematic purpose rather than simply shock value (looking at you, Game of Thrones). This gives the play a weight and maturity beyond your bread and butter thriller.

Much has been made of how unconventional this interpretation of Elizabeth I is: foul-mouthed, vulgar, self-centred and spiteful. However, no portrayal of Elizabeth in the past forty years, no matter how reverent, has omitted her famous temper and often irrational jealousy. The suggestion that Elizabeth I was actually sexually active is also not new, but used in this play for the theme of state propaganda. To the play’s credit, the portrayal of Elizabeth as foul-mouthed and violent is more of an exaggeration or an extrapolation of historical record rather than pure invention, as some reviewers of the play have suggested. The real Elizabeth did use “Jesus!” as an expletive and the story goes she once threw her shoe in Walsingham’s face (I was rather hoping to see this play out onstage, but given the number of candles it probably wasn’t a good idea). Elizabeth’s use of bad language also has motive: to gain the upper hand in her power dynamic with Walsingham through calculated degradation and humiliation. The acrimonious working relationship between the two, more toxic than any 16th century medicine, makes for the play’s best scenes.

The play’s worst scenes suffer from the flat characterisation of Lady Sidney, Walsingham’s daughter, who is two things in this play: angry and sad. This subplot is intended to show the personal cost caused by political unscrupulousness, but there’s never any sign of familial love and affection between father and daughter, meaning that the estrangement feels inevitable and therefore not much of a sacrifice. The scenes feel like they were written last minute and in a hurry, so the play and the ending suffers.

This play can be found in digital and hard copy on Amazon and I recommend it to anyone interested in history, the War on Terror, current affairs and good old-fashioned tragedy. It does not require prior knowledge of the period to enjoy, though if you are knowledgeable of the historical figures and their lives, there is much irony and nuance to be spotted and appreciated, like little Easter eggs. Licence may have been taken with the events, but historical purists (such as myself) can appreciate this play far more than they can most media set in the past.

#theatre#my writing#non fiction#Elizabeth i#the secret theatre#Sir Francis Walsingham#anders lustgarten#tara fitzgerald#feminist history#feminism#history#aidan mcardle#theatre reviews

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

someOne is coming

It is said that once in the old days in an Eastern city a poor old beggar, his body shrunken and sick and covered with sores was sent to one of the great hospitals, and after being there for some days, was taken to the operating room. In those days they did not have anesthesia, as they have now, and the patient could hear all the preparations for the ordeal.

So before the surgeon began his work on this poor old wreck of a human being, he turned to the young medical students who were in attendance and using scholarly Latin, said to them,

"Let's perform an experiment on this worthless body."

He thought his language wouldn't be understood, but this old beggar was once a great scholar himself. Although he had drifted away into liquor and sin, and had gone down the primrose path until he was just a wreck, he still understood Latin. So he lifted himself on one elbow there in the operating room and said, in perfect Latin, mind you,

"Yet for this worthless body Jesus Christ has died."

And so, friends, it might seem like a worthless body, a worthless man, a worthless, shattered, character; but always remember: Yet for this worthless one, this worthless life, Jesus Christ has died. And that puts an infinite worth on every human being. A human being is infinitely valuable. (taken from "Revival Sermons by H.M.S. Richards" 1978 Hosanna House, Hollywood, California. pp158-159)

I love talking about Jesus and what He means to me, and what He has done for me and for those around me. On my previous post we talked about how Jesus is able to save to the uttermost those who come to God through Him.

My grasp of the gospel, the good news, and my appreciation for what Jesus did and does for me, is magnified each time I study the Bible. Some may think it odd that we are spending so much time in the first few chapters of Genesis. Many tend to ignore the first 11 chapters of Genesis. Creation, the fall, the flood, these are accounts that some struggle with believing and many have tendency to downplay the importance of this portion of scriptures.

The majority of Christians seem to prefer to discuss the teachings of Jesus and the apostles. I love the New Testament. And something fascinating caught my attention as I studied the New Testament. One of them is found in the book of Acts chapter 8.

Here we have story of how Philip, a deacon, (Acts 6:5) was awakened by an angel and told to head south along the road. There he meets high ranking Ethiopian official who is returning from Jerusalem and reading Isaiah the prophet. The Ethiopian had gone to Jerusalem to worship and now the Spirit tells Philip to go and talk to the Ethiopian official.

Acts 8:35 says that Philip opened his mouth and beginning with Isaiah he preached Jesus to the Ethiopian. Philip preached the gospel, from Isaiah. Philip preached Jesus from prophetic books and the Old Testament. Which is the proper way of studying prophecy. If you are studying prophecy and you find nothing pointing to Jesus anywhere, you’re doing something wrong.

Another story that caught my attention is found in Luke 24. Here we have Jesus, after He raised from the dead, joining two disciples on the road to Emmaus. The disciples talk with Jesus without recognizing Him and Luke 24:25-27 records Jesus saying:

Luke 24:25-27 (NRSV)

25 Then he said to them, “Oh, how foolish you are, and how slow of heart to believe all that the prophets have declared! 26 Was it not necessary that the Messiah[a] should suffer these things and then enter into his glory?” 27 Then beginning with Moses and all the prophets, he interpreted to them the things about himself in all the scriptures.

Here we have Jesus helping His disciples understand His ministry by teaching them from the Old Testament. Philip used the same approach when preaching to the Ethiopian official.

The careful and prayerful study of any book of the Bible will always give us a clearer understanding of who Jesus is, what He did, what He is doing, and ultimately what He will do.

We have seen Jesus in Genesis 1 as the Word of God according to John 1. So we have God creating through Jesus. Now we will continue our study on Genesis 3 and we will find the first gospel message of the Bible.

Last time we talked about how when we sin, we are pretty much telling God that we can do a better job than Him, that we are our own masters, and we know better.

This is evident int he text when we notice how many times the text says “God saw that it was good” (Genesis 1:4, 10, 12, 18, 25, 31) and then we see the text saying “the woman saw that the tree was good…” (Genesis 3:6)

Even also behaves like God in that “she took of its fruit and… gave to her husband, and he ate.” (Genesis 3:6) The three verbs in the quotation that I italicized have so far in the story only been associated with God. God “gave” to “eat” (Genesis 1:9); God “took” the man (2:15); and God “took” one of his ribs (2:21).

If you were a reading this in Hebrew you would notice how even the verbal forms match. Eve identifies herself with the Creator and Adam follows automatically, “and she ate” and “and he ate.” (3:6)

Now for the first time in their lives Adam and Eve experience disconnection with God. They are no longer covered and protected by Him.

Psalm 104:1-2 Describes God clothed with honor and majesty covered with light as with a garment. Some believe that Adam and Eve were naked but not ashamed in Genesis 2:25 because they had similar garments of light and now Genesis 3:7 that garment of light is gone making them feel the need to cover themselves. The original text also uses different words for naked, `arowm in Genesis 2:25 and a different word `eyrom in Genesis 3:7.

Now we also read that Adam and Eve “made” themselves coverings. Guess who had been the only person making anything up to this point? So far the verb used here for “make” was used in relation to God 12 times. 12 times so far the Bible says God “made,” and now that Adam and Eve ate the fruit suddenly they are also “making.”

Remember the temptation, remember what the serpent said?

“You will be like God.”

When we read the text carefully we notice how Eve than Adam slowly begin to do things that before only God had been doing. I am not saying it is wrong to look and judge if something is good or bad, I am not saying it wrong for someone to make, build, or create. I am only pointing out how the biblical narrative portrays the subtle shifts in the story with a careful attention to how the story is told.

Many of these narrative details I have pointed out have been noticed by scholars who deny that the story ever took place. They may not believe that Adam or Eve ever really existed, but they agree the storyteller masterfully portrays their separation from God and trying to become like God in the way he tells the story. These scholars may deny that the Bible is inspired, but they regard whoever wrote Genesis as an unparalleled master storyteller.

I believe that Moses wrote the account, I believe it took place, and I believe this careful attention to detail is one more evidence of the divine inspiration of this book.

Adam and Even made themselves coverings and they heard the sound of the LORD God walking in the garden. And what do Adam and his wife do?

They hide!

Apparently their own works (Gal. 2:16) were not enough to solve their problem. What Adam and Eve made was not sufficient to take away their shame and guilt and fear.

Now God speaks to Adam and Eve and asks them a series of questions.

This is interesting because God already knows everything. So why do you think God asks questions?

“Where are you?”

Is the first question. God knows where Adam is. Adam is the one who needs to understand his position. God here is playing the role of a judge, or the prosecutor in a court of law who interrogates the culprit in order to make him realize his fault and prepare him for the forthcoming sentence. You could label this an investigative judgment. God is gathering the facts, and exposing the truth. This process, God approaching humans to confront their behavior and judge them, is a theme that is repeated multiple times in Genesis.

It is important to note that God is not asking because He lacks information, but rather for the sake of the person being judged, to help him/her understand what he/she did.

We do similar things when we hear a loud crash and see a child standing by and we know what happened, but we still ask the child what happened. We want to make sure the child understands what she did and the consequences that are about to follow.

Adam answers God’s question stating he heard God and was afraid because he was naked and he hid.

God asks another question.

“Who told you you were naked?”

“Have you eaten from the tree of which I commanded you that you should not eat?”

Adam has a golden opportunity to confess his sin and beg God for mercy. Instead he throws Eve under the buss and blames even God before stating that he did in fact eat of the tree.

“What is this you have done?”

God now asks Eve a question.

Eve follows her husband’s template and blames the serpent (indirectly blaming God who created the serpent) and acknowledges she was deceived (also a way of diminishing personal blame) and finally admits she also did eat.

After God has asked these questions and Adam and Eve are both aware of what they did, God proceeds to the next part of the judgment. He pronounces the sentence.

The sentence begins with the serpent. No questions are asked, the serpent has no excuse. The serpent is cursed because of its actions, because of what Adam and Eve said.

At the end of the sentence on the serpent we have the first gospel message, or the first messianic prophecy

"And I will put enmity Between you and the woman, And between your seed and her seed; He shall bruise you on the head, And you shall bruise him on the heel.”" -- Genesis 3:15 NASB

God places enmity, hostility, between the serpent and the woman, between the seed of the woman and the seed of the serpent.

The seed can be understood as a reference to offspring, but because of the sentence that follows. “He shall bruise your head” we notice that the seed is also referring to a specific person who will defeat the serpent but also suffer in the process.

In the midst of the judgment, in the heart of the the chapter, we have a messianic prophecy, we have good news!

The serpent will be defeated!

SomeOne is coming!

The rest of the Old Testament will tell us more about this theme, and about what He will do. The Old Testament is all about announcing that someOne is coming to defeat the serpent.

By the end of the chapter God has to “make” one more thing. God made tunics of skin and clothed them. God could have made them clothes out of cotton or silk, but God made them tunics of skin. For Adam and Even to be clothed an animal had to die. Remember, the serpent would bruise the heel of the seed. To defeat the serpent, to solve the sin problem, there would be a cost. For Adam and Eve to be covered and innocent animal had to die.

Adam and Eve were given hope. Ultimately, the serpent would be defeated. SoneOne was coming! But until that day, there were consequences because of their choice, because of their sin. Their disobedience caused them to be banished form the garden and from access to the tree of life. The death process would now begin.

But in the midst of the sadness and guilt and regret. Adam and Eve had a hope to hold on to. for God had told them.

SomeOne is coming!

0 notes