#interaction bertram and rose

Text

—No esperaba encontrarte aquí— expresó el chico con una gran sonrisa cuando se encontró a Rose en la fiesta de Sturgis, pero sin duda le alegraba ver que ya estaba saliendo más pues aparte de estar enamorado de ella, la consideraba una amiga —¿quieres que busquemos algo de beber?— la curiosidad era más que notable en su voz.

@thcgoodwitch

#THIS NIGHT IS SPARKLING DONT YOU LET IT GO#[ ☔ ] : bad luck boy ➜ bertram aubrey➜interaction#interaction bertram and rose

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

ARC Review: Curled Up with an Earl by Amy Rose Bennett

3.5/5. Releases 2/7/2023.

For when you're vibing with: nerdy heroines, a bit of servant/rich girl (but not really), mystery in your romance, and a looming villain.

Lucy Bertram is in a tight spot: her father wants her to marry an odious man for the sake of her family, and her brother (who would normally be in her corner) is missing. Little does she know that there's an investigator (investigating something else, but still) right under her nose in the form of the new groom Will, who's actually the Earl of Kyle and an agent of the Crown. Will could come in handy for Lucy--but there is that issue of his overwhelming attraction to her...

This one was a mixed bag for me--I really liked aspects of it, and others I found harder to follow. Part of this may be that I'm just not the right reader for the book; I think that mystery subplots can be hard for me to follow in romances. However, I really did like the pacing of the book, and the sex scenes were frankly pretty bomb.

Quick Takes:

--Having read two Amy Rose Bennett books (both of which I had a mixed reaction to) for me the standout is really how she handles the sexuality of her heroines. Lucy is a virgin, but as a nerdy heroine, she's not completely in the dark about the physicality of sex. Furthermore, she's super enthusiastic about learning! I also really loved the amount of sex in this book--and while, how it did lead up to in v, that wasn't the end all be all. Both Lucy and Will treated the non-penetrative sex they had as really physically and emotionally important. This is something you don't find in a lot of het romance, and especially not in a lot of het historical romance.

--The mystery... It was just hard for me to get into. I kind of wish that Will had just been--actually a groom. I liked the villain trying to marry her, I liked their interactions, but the mystery was just... Not hard to follow, but not connecting with me. Again, that might just be me as a reader; I've had mysteries work for me in romances, but here it just didn't and it did feel like it took away from the love story.

--While I enjoyed Will and Lucy's chemistry and dynamic, I do think that if the mystery hadn't been so in focus, we could've gotten more focus on them and their personal flaws and issues and conflicts as a couple. I don't need a romance to be conflict central (though I love conflict) but to me, when I don't see a couple come up against each other (non-sexually) at some point, I kind of wonder about their long term romantic viability...? I don't know, I guess I as a reader just want a bit more oomph to my leads, even if they're not in an enemies to lovers situation (which to clarify, these two are not).

I definitely want to read more from Amy Rose Bennett. I like her writing style a lot, I just don't know if I've come up on the right plot from her for me. However, if you do like a bit of a cozy mystery vibe, if you enjoy a nerdy heroine and a bit of an undercover situation, you will probably love this book.

Thank you to Netgalley and Sourcebooks Casablanca for providing me with a free copy of this book in exchange for an honest review.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

“...It is easy to treat the eighteenth century as a unit: to use a modern concept, the “long eighteenth century,” generally seen as 1689–1815. However, this period was not static or uniform. Instead, the situation when Austen was born was changing rapidly, as contemporaries were well aware. Indeed, Thomas Malthus, a cleric from a clerical background, addressed population issues, publishing An Essay on the Principle of Population in 1798. This warning about the problems stemming from population growth is one perspective on the five Bennet children and the Heywoods’ fourteen, which greatly affected their living standards.

Malthus’s arguments are echoed in the more unpleasant and personal reflections of the childless Mrs. Norris on the nine children of her impoverished sister Frances, Mrs. Price. Her wealthier sister, Maria, Lady Bertram, is not the target of such criticism, but she also has fewer children. Whereas England averaged an annual population increase of 0.3 percent in 1700–55, between 1755 and 1801 the increase was 0.8 percent. As a result, the population of England and Wales rose from 6.20 million in 1751 to 8.89 million in 1801. It went on to grow to 10.16 million in 1811 and 12 million in 1821, a rapid rate of increase. This increase was particularly visible in the expansion of cities, including the largest, London.

Rural England was both hierarchical and changeable—like its urban counterpart but differently so. The economic transformation of rural England is addressed in part in the next chapter, but change was not only a matter of the agricultural revolution and its limits. The social imprint of this change was of most interest to novelists. Social patterns were the product of dynamic relationships, especially the daily reaffirmation of status; the continuous interaction between, and within, groups; and the multiple links of friendship, kinship, and patronage. In England, there was no fixed, caste-like rigidity, which would have left scant room for social mobility. Instead, there was an active land market, as well as the impact of agrarian fortune or failure.

Alongside such shifts, the weight of the past was apparent in the distribution of wealth, status, and power, which were all factors to the fore in Austen’s world, not least in the matrimonial stakes. During her lifetime, there was scant change in the ways individuals could determine or change their social position. Certainly, in comparison with the following two centuries, the rate of social change was low. However, that does not imply there was little social change. In addition, although it cannot be measured with precision, social mobility was greater than on the Continent, as was the interaction of social groups. Status and power were linked to wealth, although they were not identical with it.

This situation was repeatedly probed by writers, including Austen in her major works and especially in Sanditon, a late work of the postwar period that is particularly sensitive to the issue. This linkage of status, power, and wealth was generally regarded as appropriate in English society. However, at the same time, there was a long-standing degree of tension over the terms of this linkage, as well as the definition of acceptable wealth, and notably of land as opposed to other forms. Related to this, the traditional vocabulary of social “orders” appeared less relevant. The legitimacy of money, which many saw as disruptive, as opposed to landed wealth, was a continuing matter of controversy.

Certainly it was disruptive as far as the matrimonial stakes were concerned. The relationship between capital and income greatly favored the former. Indeed, the ability to create income without capital was limited, which helped increase the tendency to borrow and thus the role of credit. Nevertheless, despite the role of inherited capital, opportunities for self-advancement from imperial expansion or industrialization existed. Men who had earned their money in India and the West Indies made their mark, creating positions back in English society, as in Mansfield Park. In Sanditon, Miss Lambe, an heiress from the West Indies, is one of the young women whose education is being finished under the care of Mrs. Griffiths: “She was about seventeen, half mulatto, chilly and tender.”

The chilly is best explained as a reference to the cold of Britain after the West Indies. Although the Bertrams of Mansfield Park are not criticized, certainly not explicitly, for earning their money in part from a plantation in Antigua, a British island colony in the West Indies where sugar was cultivated, those who had earned their money abroad could in fact arouse suspicion. Samuel Foote’s play The Nabob illustrated the disdain with which people treated new money made in the empire, as was the case with Warren Hastings, an empire builder in India who was tried for corruption in one of the great political spectaculars of the age. Fanny Burney, who attended the trial, was very sympathetic toward Hastings.

As was known within the family, Hastings may have been the true father of Austen’s cousin Eliza, although this claim was much disputed. Eliza certainly was a product of women being sent to the colonies to find a husband, as discussed by Austen. Self-advancement also came from trade, which was an issue as a source of money and social uncertainty. Austen sometimes was positive about those who had made money through trade. The Coles in Emma and, far more, the Gardiners in Pride and Prejudice fall into this category. In contrast, in Emma the Sucklings, the family of Mr. Elton’s wife, are mercilessly caricatured for their concern (at least as expressed through Mrs. Elton) with material goods and status.

At the same time, in a multilayered response, Mrs. Elton’s concern is in part a matter of her almost painful uncertainty about her social and personal position. Money gained through trade and other means can be honorable, but valuing people only in terms of their wealth is very much not, according to Austen: John Dashwood eyed Colonel Brandon “with a curiosity which seemed to say, that he only wanted to know him to be rich, to be equally civil to him.” Many former London merchants had moved out of the capital—for example, the Heathcote family of Horsley. The care taken by the newly affluent to buy status helped ensure they did not undermine notions of social hierarchy.

Indeed, the very existence of social distinctions was seen as obvious and arising from the natural inequality of talents and energies. Egalitarianism found favor with few writers on social topics, and social control by the elite was a fact. These assumptions pervaded society, encouraging the ranking by birth and snobbery that features so prominently in Austen’s novels and through which characters establish their personality and the plot advances. The desire to preserve family status and wealth in part lay behind Hardwicke’s Marriage Act of 1753, which increased the power of parents by outlawing clandestine marriages in England, a crucial challenge to the marriage market and the related social assumptions.

This act encouraged couples to elope to Gretna Green just into Scotland, where Lydia Bennet is (wrongly) feared to have gone in Pride and Prejudice. In 1774, Robert Nugent, an opportunist in all things including his marriages, attacked the act in the House of Commons as “tending to prevent an union of willing hearts, and to hinder young girls from giving their hands to such hearty young men as they could like and love, in order that miserly parents might couple youth with age, beauty with deformity, health with disease.” Certainly, the power of fathers over the marriage of children, particularly daughters, emerges repeatedly in Austen’s novels. Far less so for sons, but it is still a factor.

The desire to preserve family status and wealth by controlling marriage, as seen in Hardwicke’s Marriage Act, was also crucial to the system of entail (a limitation of the inheritance of property) that threatened the future of the Bennet women in Pride and Prejudice. Under this system, the entire estate would be inherited by the next male relative—in their case, a cousin, the egregious Mr. Collins. This arrangement, which Mr. Bennet regrets, explains Mrs. Bennet’s eagerness for Mr. Collins to marry Elizabeth and thereby keep access to the property and her somewhat extreme anger when Elizabeth turns him down. Somewhat differently, the death of George Austen in January 1805 left his wife and unmarried daughters in a difficult position, rather like that of the clergyman in The Watsons.

Social differentiation, or at least an awareness of distinctions of rank and status, may have become more acute in this period in response to social mobility and the pressures of commodification that commercialism created, although neither element was new. This concern about mobility owed much to the degree to which heredity and stability were regarded as intertwined. Yet Lady Catherine de Bourgh and Sir Walter Elliot are scarcely presented by Austen as exemplars of hereditary rank, although neither, interestingly, was at the height of society, unlike Darcy or, to a lesser extent, Fitzwilliam.

Concern to keep land within families, or, more particularly, their male line, is seen with the role of the entail, not only for the Bennets in Pride and Prejudice and the Dashwoods in Sense and Sensibility but also for Sir Walter Elliot in Persuasion: “He had condescended to mortgage as far as he had the power, but he would never condescend to sell. No; he would never disgrace his name so far.” Sir Walter repeatedly emerges in a very poor light, and even more because the book was published at a time of postwar economic problems and of concern with the related tensions. His wartime attitudes are clearly unacceptable. He thought Frederick Wentworth, a naval hero, “a very degrading alliance” for his daughter Anne.

A man without a “fortune,” the hero had “no connexions” to secure even his farther rise in that profession. The obsession with rank and the practice of condescension seen with Sir Walter affect other relatives; faults were corrosive and generally operated through condescension, as with Lady Catherine and the Bingley sisters, Caroline and Louisa. The baronet’s married daughter, Mary, expects precedence over her mother-in-law because of her inherited rank. Yet, as with many writers, criticism of an individual was not criticism of an entire order but rather a call for good behavior by its members.

Austen’s mother was proud of the aristocratic connections of her family, the Leighs, although the most distinguished—James, first Duke of Chandos (Austen’s great-grandfather married one of his sisters)—was a connection that was shadowed by the financial problems of Henry, the second duke, which led, in 1747, to the demolition sale of the family seat, Cannons in Middlesex. That was not an Austen-like plot. A more attractive (and recent) experience was provided by Austen’s brother Edward, who was adopted by a wealthy, childless, distant cousin, Thomas Knight. Edward married well in 1791 and changed his name in 1812 to inherit the Knight family estates, but he did not cut himself off from the Austens.

Indeed, far from it. Austen was well aware of the peerage and used current names for some of her characters. She also captured the gradations of expectation in the social elite very well in a conversation between Colonel Fitzwilliam and Elizabeth Bennet. The former contrasts himself with his cousin Darcy: “He is rich, and many others are poor. I speak feelingly. A younger son, you know, must be inured to self-denial and dependence.” This earns the rejoinder: “In my opinion, the younger son of an Earl can know very little of either. Now, seriously, what have you ever known of self-denial and dependence? When have you been prevented by want of money from going wherever you chose or procuring any thing you had a fancy for?”

In turn, Colonel Fitzwilliam correctly notes: “Younger sons cannot marry where they like.” This rules out Elizabeth for him, which represents his loss. Austen presents this problem more generally and for women as well as men. Social status is clearly understood as finely graded, but that can also be made inappropriate, at least to a degree, as with the discussion of Lady Russell’s attitude toward Sir Walter Elliot: “She was as desirous of saving Sir Walter’s feelings, as solicitous for the credit of the family, as aristocratic in her ideas of what was due to them. . . . She had prejudices on the side of ancestry; she had a value for rank and consequence, which blinded her a little to the faults of those who possessed them. Herself, the widow of only a knight, she gave the dignity of a baronet all its due.”

At the same time as the emphasis on lineage, there was a growing sense that status, instead, should be a matter of conduct. In contrast, indeed, Austen links “pride and ill nature” in the case of Mrs. Ferrars. The stress on civil as much as social virtue contributed to the importance of conduct judged polite and reflected it. Yet, if morality was increasingly prescribed, and indulgence proscribed, this process represented not a middle-class reaction against noble culture but a shift in sensibility common to both. For every decadent aristocrat depicted on the stage in the second half of the eighteenth century, there were several royal or aristocratic heroes.

Thus, rather than seeing the commercialization of leisure as a triumph for middle-class culture, the role of the middle class was largely one of patronizing both new and traditional artistic forms and emulating the aristocracy, rather than developing or demanding styles that were distinctive, consciously or otherwise. Indeed, George III played a key role in exemplifying a moral purposefulness that fitted with Austen’s values. From a different perspective, the expansion and profitability of the commercial and industrial sectors of the economy led to a growth in the middling orders, who were increasingly difficult to locate in terms of a social differentiation based on rural society and inherited position.

Moreover, thanks to an active land market, status could be readily acquired by the wealthy. By 1790, about one-fifth of the membership of the House of Commons came from backgrounds outside the landed elite. This mobility strengthened, rather than weakened, the social hierarchy, whatever Sir Walter might have thought. At the same time, social flux led some to emphasize social distinctions. This represents the range of responses that can be described as Tory, one of the two major political traditions of the century. Social differentiation was reflected in a range of activities and spheres, such as sport and dress, and, more generally, in conversation and socializing—for example, visiting and receiving visitors.

Hunting, a key aspect of socializing, was restricted to the affluent by the laws that entrenched this differentiation. These laws were maintained by gamekeepers and mantraps, and both the legislation and its defense helped make clear the nature of hierarchy and power in the rural community. Hunting was restricted by legislation, and, keeping horses, especially hunting horses, was expensive. Mr. Bingley returns to Netherfield for the shooting, another very expensive process redolent of status. This point is discussed further in the next chapter. The seating arrangements in churches, and the treatment of the dying and their corpses, also reflected social status and differences, as did the provision of health care: only the wealthy could afford church pews, indoor tombs, and fashionable doctors.

Patterns and practices of crime and punishment, credit and debt, also reflected social distinctions. Aristocratic debtors escaped the imprisonment for debt that was a frequent consequence of the role of credit in society. Power and wealth were concentrated. The hierarchical nature of society and of the political system, the predominantly agrarian nature of the economy, the generally slow rate of change in social and economic affairs, the unwillingness of governments composed of the social elite to challenge fundamentally the interests of their social group or govern without their cooperation, and the inegalitarian assumptions of the period all combined to ensure that the concentration of power and wealth remained reasonably constant.

The old order could be “insolent and disagreeable,” as in the person of Lady Catherine de Bourgh. This arrogance was particularly directed against those seen as challenging the instrumental assumptions of the elite about others, as with Lady Catherine’s consistently harsh and condescending response to Elizabeth Bennet. Across Europe, those who enjoyed power and wealth tended to be nobles/aristocrats by birth or creation. In Britain, accordingly, the peerage dominated government, politics, and the military. All adult, male, non-Catholic English peers were members of the House of Lords, and only they were eligible for membership. The sole male peers were heads of families and thus the current chiefs of respective lineages.

The peers were influential collectively, as well as often individually. In 1782–1820, fifty-seven of the sixty-five ministers were peers or the sons of peers. Moreover, most new peers were relations of existing ones. There were 189 male peers in 1780 but, due to many creations, 220 by 1790. The size of the English peerage was far smaller than that on the Continent because the ownership of a significant amount of land was not itself an indication or cause of noble rank. However, the (nonaristocratic) gentry who had such land enjoyed considerable social status. There was an active land market, and, by European standards, land and status could be readily acquired.

Nevertheless, marriage and inheritance, rather than purchase, remained the crucial means by which land was transferred. Moreover, surname substitution, a frequent practice, helped strengthen a sense of continuity in land ownership while the pattern of estates itself did not alter. The socially prominent who were wealthy, famously the “single man in possession of a good fortune,” were the prime catches in the marriage market and thus best able to preserve and increase their wealth by marriage. Lady Catherine de Bourgh was simply stating the obvious about the pattern of social endogamy when she haughtily informed Elizabeth Bennet in a truly dramatic clash of values (and personalities) where Austen’s opinion is clear:

“My daughter and my nephew [Darcy] are formed for each other. They are descended on the maternal side, from the same noble line; and, on the father’s, from respectable, honourable, and ancient, though untitled families. Their fortune on both sides is splendid. They are destined for each other by the voice of every member of their respective houses; and what is to divide them? The upstart pretensions of a young woman without family, connections, or fortune.” Elizabeth’s first retort is that she is “a gentleman’s daughter.” Lady Catherine crushes this by asking: “But who was your mother? Who are your uncles and aunts?”

After thus being told she is a nobody, Elizabeth responds with the more pointed and radical response: “Whatever my connections may be, if your nephew [Darcy] does not object to them, they can be nothing to you.” This response is a determined statement in favor of individualism, youth, and personal attraction over caste and age. This statement is also significant for the dynamics of female relationships, including between the generations. These dynamics are easily as significant in Austen’s books as male-female relations.

At the same time as Elizabeth’s robust response, Elizabeth’s mother, Mrs. Bennet, jealously maintained downward social distinctions, as with her determination to differentiate the accomplishments of her daughters from the occupations of her servants: “I always keep servants that can do their own work; my daughters are brought up differently” and “assured him with some asperity that they were very well able to keep a good cook, and that her daughters had nothing to do in the kitchen.””

- Jeremy Black, “Rural England: The Epicenter of Austen’s World.” in England in the Age of Austen

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

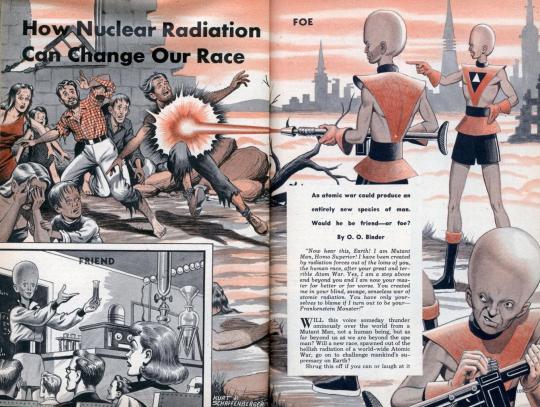

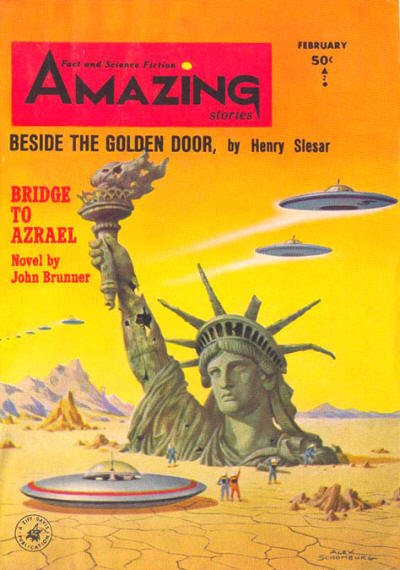

Top Misconceptions People Have about Pulp-Era Science Fiction

A lot of people I run into have all kinds of misconceptions about what pulp-era scifi, from the 1920s-1950s, was actually like.

“Pulp-Era Science Fiction was about optimistic futures.”

Optimistic futures were always, always vastly outnumbered by end of the world stories with mutants, Frankenstein creations that turn against us, murderous robot rebellions, terrifying alien invasions, and atomic horror. People don’t change. Then as now, we were more interested in hearing about how it could all go wrong.

To quote H.L. Gold, editor of Galaxy Science Fiction, in 1952:

“Over 90% of stories submitted to Galaxy Science Fiction still nag away at atomic, hydrogen and bacteriological war, the post atomic world, reversion to barbarism, mutant children killed because they have only ten toes and fingers instead of twelve….the temptation is strong to write, ‘look, fellers, the end isn’t here yet.’”

The movie Tomorrowland is a particulary egregious example of this tremendous misconception (and I can’t believe Brad Bird passed on making Force Awakens to make a movie that was 90 minutes of driving through the Florida swamps). In reality, pre-1960s scifi novels trafficked in dread, dystopian futures, and fear. There was simply never a time when optimistic scifi was overrepresented, even the boyish Jules Verne became skeptical of the possibilities of technology all the way at the turn of the century. One of the most famous pulp scifi yarns was Jack Williamson’s The Humanoids, about a race of Borg-like robots who so totally micromanage humans “for our own protection” that they leave us with nothing to do but wait “with folded hands.”

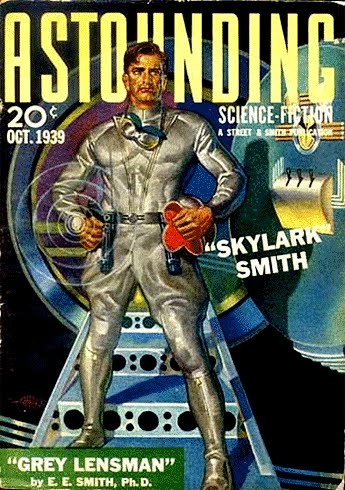

“Pulp scifi often featured muscular, large-chinned, womanizing main characters.”

Here’s the image often used in parodies of pulp scifi: the main character is a big-chinned, ultra-muscular dope in tights who is a compulsive womanizer and talks like Adam West in Batman. Whenever I see this, I think to myself…what exactly is it they’re making fun of?

It’s more normal than you think to find parodies of things that never actually existed. Mystery buffs and historians, for example, can’t find a single straight example of “the Butler did it.” It’s a thing people think is a thing that was never a thing, and another example would be the idea of the “silent film villain” in a mustache and top hat (which there are no straight examples of, either). There are no non-parody examples of Superman changing in a phone booth; he just never did this.

In reality, my favorite description of pulp mag era science fiction heroes is that they are “wisecracking Anglo-Saxon engineers addicted to alcohol and tobacco who like nothing better than to explain things to others that they already know.” The average pulp scifi hero had speech patterns best described as “Mid-Century American Wiseass” than like Adam West or the Lone Ranger.

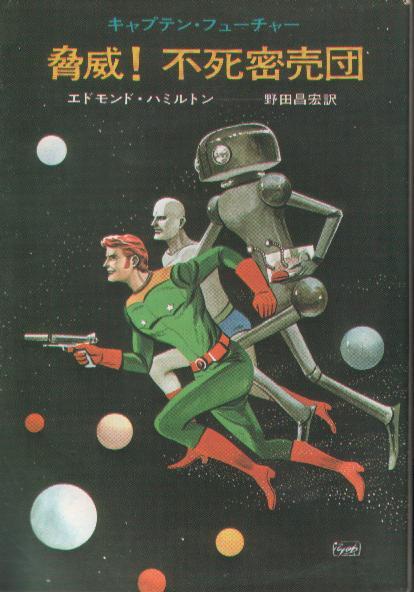

The nearest the Spaceman Spiff stereotype came to hitting the mark was with the magazine heroes of the Lensmen and Captain Future, and they’re both nowhere near close. Captain Future was a muscular hero with a chin, but he also had a Captain Picard level desire to use diplomacy first, and believed that most encounters with aliens were only hostile due to misunderstandings and lack of communication (and the story makes him right). He also didn’t seem interested in women, mostly because he had better things to do for the solar system and didn’t have the time for love. The Lensmen, on the other hand, had a ruthless, bloodthirsty streak, and were very much like the “murder machine” Brock Sampson (an attitude somewhat justified by the stakes in their struggle).

“Pulp Era Scifi were mainly action/adventure stories with good vs. evil.”

This is a half-truth, since, like so much other genre fiction, scifi has always been sugared up with fight scenes and chases. And there was a period, early in the century, when most scifi followed the Edgar Rice Burroughs model and were basically just Westerns or swashbucklers with different props, ray guns instead of six-shooters. But the key thing to remember is how weird so much of this scifi was, and that science fiction, starting in the mid-1930s, eventually became something other than just adventure stories with different trappings.

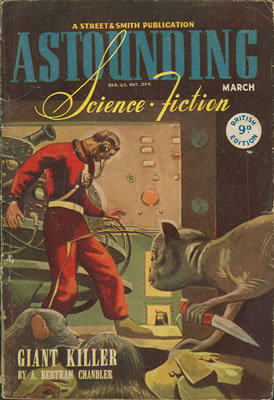

One of my favorite examples of this is A. Bertram Chandler’s story, “Giant-Killer.” The story is about rats on a starship who acquire intelligence due to proximity to the star drive’s radiation, and who set about killing the human crew one by one. Another great example is Eando Binder’s Adam Link stories, told from the point of view of a robot who is held responsible for the death of his creator.

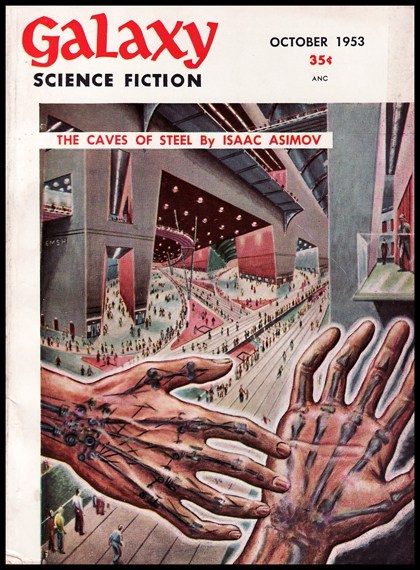

What’s more, one of the best writers to come out of this era is best known for never having truly evil bad guys: Isaac Asimov. His “Caves of Steel,” published in 1953, had no true villains. The Spacers, who we assumed were snobs, only isolated themselves because they had no immunities to the germs of earth.

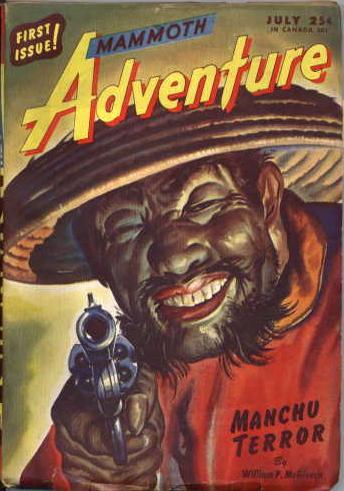

“Racism was endemic to the pulps.”

It is absolutely true that the pulps reflected the unconscious views of society as a whole at the time, but as typical of history, the reality was usually much more complex than our mental image of the era. For instance, overt racism was usually shown as villainous: in most exploration magazines like Adventure, you can typically play “spot the evil asshole we’re not supposed to like” by seeing who calls the people of India “dirty monkeys” (as in Harold Lamb).

Street & Smith, the largest of all of the pulp publishers, had a standing rule in the 1920s-1930s to never to use villains who were ethnic minorities because of the fear of spreading race hate by negative portrayals. In fact, in one known case, the villain of Resurrection Day was going to be a Japanese General, but the publisher demanded a revision and he was changed to an American criminal. Try to imagine if a modern-day TV network made a rule that minority groups were not to be depicted as gang bangers or drug dealers, for fear that this would create prejudice when people interact with minority groups in everyday life, and you can see how revolutionary this policy was. It’s a mistake to call this era very enlightened, but it’s also a mistake to say everyone born before 1970 was evil.

“Pulp scifi writers in the early days were indifferent to scientific reality and played fast and loose with science.”

FALSE.

This is, by an order of magnitude, the most false item on this list.

In fact, you might say that early science fiction fandom were obsessed with scientific accuracy to the point it was borderline anal retentive. Nearly every single one of the lettercols in Astounding Science Fiction were nitpickers fussing about scientific details. In fact, modern scifi fandom’s grudging tolerance for storytelling necessities like sound in space at the movies, or novels that use “hyperspace” are actually something of a step down from what the culture around scifi was in the 1920s-1950s. Part of it was due to the fact that organized scifi fandom came out of science clubs; Hugo Gernsback created the first scifi pulp magazine as a way to sell electronics and radio equipment to hobbyists, and the “First Fandom” of the 1930s were science enthusiasts who talked science first and the fiction that speculated about it second.

In retrospect, a lot of it was just plain obvious insecurity: in a new medium considered “kid’s stuff,” they wanted to show scifi was plausible, relevant, and something different from “fairy tales.” It’s the same insecure mentality that leads video gamers to repeatedly ask if games are art. You’ve got nothing to prove there, guys, calm down (and take it from a pulp scifi aficionado, the most interesting things are always done in the period when a medium is considered disposable trash).

One of the best examples was the famous Howard P. Lovecraft, who published “The Shadow out of Time” in the 1936 issue of Astounding. Even though it might be the only thing from that issue that is even remotely reprinted today, the letters page from this issue practically rose up in revolt against this story as not being based on accurate science. Lovecraft was never published in Astounding ever again.

If you ever wanted to find out what Star Wars would be like if they were bigger hardasses about scientific plausibility, check out E.E. Smith’s Lensman series. People expect a big, bold, brassy space opera series with heroes and villains to play fast and loose, but it was shockingly scientifically grounded.

To be fair, science fiction was not a monolith on this. One of the earliest division in science fiction was between the Astounding Science Fiction writers based in New York, who often had engineering and scientific backgrounds and had left-wing (in some cases, literally Communist) politics, and the Amazing Stories writers based in the Midwest, who were usually self taught, and had right-wing, heartland politics. Because the Midwestern writers in Amazing Stories were often self-taught, they had a huge authority problem with science and played as fast and loose as you could get. While this is true, it’s worth noting science fiction fandom absolutely turned on Amazing Stories for this, especially when the writers started dabbling with spiritualism and other weirdness like the Shaver Mystery. And to this day, it’s impossible to find many Amazing Stories tales published elsewhere.

3K notes

·

View notes

Note

1, 5, 10, 15!

1. your favorite face claims

oh boy. marina laswick, adelaide kane, stephen james, ben barnes, avan jogia, stephanie rose bertram, fei fei sun, meisa kuroki, tom kaulitz, thomas davenport, corentin huard, david beckham, kit harington, daniel bederov, emma watson, aaron taylor-johnson.

5. your favorite original-verse oc (or one of your favorites)

if i’m being honest, my favorite original-verse oc is one of my opp’s on another site and his name is garrett watson. he’s the cutest little button of selflessness and he’s just one of my favorite characters to write against. it’s one of my favorite ships in the entire world. like, i’ll go down with this ship tbh.

10. a fandom character who you would like to interact with

ok so is this one like, if i were irl who would i want to meet? because 10/10 if i got to hang with luna lovegood i’d be on that shit like white on rice. if we’re talking a character from a fandom rp someone give me a reason to plot with the hymn potter family they seem so pure ok.

15. your favorite rp otp

maleigh. otp forever honestly. of mine though, probably decelle?

0 notes