#jean paul marat

Text

"And what shall be the reward of spilling so much blood, one drop of which has more worth than all the crowned heads of the world?"

L’Ami du Peuple, No 634, from Thursday 19th April 1792.

[The very next day, on the 20th April 1792, war was declared against Austria]

If it was still impossible to doubt the traitorous dispositions of the court, after all the plots that it has formed to this day, in order to crush the people, to ruin the nation, and to re-establish despotism, the scene of high scandal that the ministerial cabinet has just been playing out should have sufficed to open the eyes of all.

On the 14th of this month, the ministers presented themselves in the Assembly. The Minister of Foreign affairs [Dumouriez; he took this post on 15th March 1792] took the floor to communicate to them, after the orders of the king, of the dispatches that, he said, were delivered by an extraordinary courier who arrived during the night. He first read out the letter written [by Louis XVI] to sieur [Louis Marie Antoine, Vicomte de] Noailles, ambassador at the court of Vienna, demanding the new king of Hungary [Franz II of the Holy Roman Empire, nephew of Antoinette] to give a categorical response on his attitudes towards France. He then read out the response of sieur Noailles, containing a formal refusal to continue a negotiation that he [Noailles] said was impracticable and an announcement of his [Noailles’s] resignation. He [Dumouriez] proceeded to give a reading of a very pressing dispatch [from Louis XVI] addressed to sieur Noailles. Finally, he [Dumouriez] announced that Louis XVI had just written in his own hand a letter to the king of Hungary, and sieur Molle the field marshal was to deliver it. The response to this letter would arrive on the 10th of next month at the latest and would decide whether peace or war would be. In this epistle, one can clearly sense that Louis XVI is repeating his crude joke of professing his love for the Constitution.

Scarcely had these readings been finished than sieur Briche and sieur Guadet demanded a decree of indictment against sieur Noailles for having disobeyed the orders of the king; they must say so, for he had betrayed the interests of the nation and compromised public safety. After several light debates, this decree was given a near-unanimous pass. Already the ones that did not follow the thread of the story were singing to their victory, for they saw that he was declared a nation-harming (lèse-nation) criminal, he who is an ambassador of France, a close relative (cousin-germain) to sieur Motier [Noailles and Lafayette had the same father-in-law], a member of the Tuileries committee, and a pillar of the Feuillant club; that is to say, one of the main conspirators, bolstered by all the forces of his accomplices, and sure of the support of the vast majority of counter-revolutionary conscript fathers. But their joy was short-lived. Several hours after the decree of indictment, the veil was ripped to lay bare the juggleries of the ministerial cabinet. Sieur Dumouriez appeared on stage to announce to the president a letter that he had allegedly just received from sieur Noailles, who had finally obeyed the orders of Louis XVI and had given news that the king of Hungary refused all negotiations, declaring war on the French nation.

Immediately Thuriot, Goupilleau, Vaublanc, Gentil, Dumas *and the other gangrenous ministers demanded that the decree of indictment be revoked. Sieur Kersaint and Sieur Delacroix ⁑ proposed that the letter of the minister [Dumouriez] and the dispatch of the ambassador be sent back to the diplomatic committee, so that the report would be done on time.

The report done, under the name of the committee, by sieur Lasource, the decree of indictment was adjourned. Such was the conclusion of the ministerial and senatorial farce against sieur Noailles. Thus, by the method of a double correspondence, the perfidious agents of the prince will always get away with their deeds, just like how pirates escape by the method of using false flags. Always the artifices of the court will render the laws illusory; always the apparent acts of justice from the legislator will be none but lures to deceive the people; and no matter how things turn out, always the public enemies at the helm of the vessel of the State will manage to throw it at the reefs, and to direct it in such a way as that shall see it broken by the storm and engulfed by the waves in the end.

So finally here is war declared on the French by the powers plotted against freedom. However, who does not see that all these pretend ministerial negotiations with foreign courts had no other goal than to amuse the nation and to buy time, until all these powers have their batteries loaded, and they are ready to shoot us? Who does not see that all these bellicose preparations, arranged by the Assembly, had no other goal than to lure the nation to sleep in deep dreams of security? Who does not see that all these sending-back to the executive power, the denunciations, the prevaricating ministers, and these complaints of citizen soldiers crammed onto the frontiers and left without munitions, without weapons, without clothes, without pay, had no other goal than to leave the patrie with no means of defence, to leave the State in the grip of the machinations of the court, of the undertakings of the fugitive plotters, of the attacks of the foreign lackeys.

Will there be war? Everybody is saying yes. It is certain that this opinion has finally prevailed in the cabinet, after the representations of sieur Motier who, without doubt, has made it the only way in order to distract the nation from the concerns within to occupy with concerns without, in order to make the nation forget the internal dissensions in favour of news in gazettes, in order to dissipate the national property into military preparations, instead of employing it to liberate the State and to comfort the people, in order to crush the Nation under the feet of taxes, and in order to slit the throats of patriots of the infantry and of the citizen army, leading them to the butcher’s, under the pretext of defending the barriers of the empire.

It is always certain that he pressures the monarch to stop negotiating and to order the campaign to be started, which he regards as a means to honourably end his own career, if he runs out of ways to regain the nation’s confidence with new acts of seduction and of hypocritical devotion to the cause of liberty.

Lost in the heady rhetoric from Brissot, from Lemontey, from Girardin, from Delacroix, from Gouvion, from Dumas and from other scoundrels who have sold themselves to the court, seduced by a false image of national forces, intoxicated by the fumes of Gallic boastfulness, the people seem no less desiring for war than their implacable enemies do. For three years I have represented war as the last resort of counter-revolutionaries and I have not stopped working to thwart the various undertakings of the cabinet to set it aflame. Since then, my attitude has not changed, and in my eyes, war is always the cruellest curse that may be cast on the kingdom. Whatever new focus that war will draw public attention to, by only fixing it onto news in gazettes, war will leave an open field for the enemies within to machinate at their ease and to breathe the fire of civil dissensions into all parts of the kingdom, to instigate troubles, and to set traps for proponents of freedom; the war will completely squander the national property and accelerate public bankruptcy; the war will consummate the loss of everything that France has in good citizens and it will drain the State of all the patriotic youth, because it is the most zealous proponents of the revolution who have been rushing to the defence at the frontiers, and they will always do so.

However fearless they may be, they are without weapons ¹, without discipline, without tactics, without idea of grand manoeuvres ², without the smallest notion of the art of war, without experienced chiefs, without shrewd and faithful generals. How would the soldiers of the patrie resist the attacks from the disciplined armies of lackeys, they who are commanded by shrewd generals?

If war happens, I repeat, regardless of the bravery of the defenders of freedom, it does not take an eagle-eyed genius to foresee that our armies will be crushed in the first campaign.

I can conceive that the second campaign would be less disastrous and that the third could even be a glorious success, since it is impossible that we would not learn at our own expense, impossible that some great man would not be given a position. Yet, to wrest victory from our enemies, we will need to suffer a long and disastrous war. Now, it would fall short of the truth, to say that our losses, over three campaigns, shall round to a billion livres and five hundred thousand combatants.

How shall we compensate for the loss of so many brave soldiers, the flower of the French citizens? And what shall be the reward of spilling so much blood, one drop of which has more worth than all the crowned heads of the world? To prevent this precious blood from being shed, I have proposed for a hundred times an infallible method, which is to take hostage among us Louis XVI, along with his wife, his son, his daughter, his sisters ⁂, and hold them accountable to what happens. A senate faithful to the patrie will speak to him thus: “King of the French, it is in vain that you (vous) hide in the detours of a tortuous policy to see us ensnared in the disasters of war; you have no escape from the avenging power of the people. We declare to you, in the name of the nation, who is your august sovereign, that we do not wish to deal with your fellowmen, the princes of Europe, that we wish to make no preparations at all for war. Whether or not you compromise with them is your choice. The duty to remind your rebellious brothers and cousins is upon you, and so is the duty to divert your fellowmen from all hostile undertakings. The barriers of the State will stay open, yet rest assured that upon certain news that the first corps of enemies shall have crossed them, your culpable head will roll at your feet, and your entire dynasty shall be extinguished in its own blood.”

But a senate faithful to the patrie is even rarer than a patriotic king. How insensible the people is, that they do not sense the necessity to finally choose a supreme dictator, to give him powers that would be circumscribed, so that he would have no authority to dominate, but unlimited authority to cut down the chief conspirators that the public voice has identified, to force the corrupt legislator to put at a price the heads of kings, of princes and of the generals who will come with weapons against us, to offer sums of gold to their troops who will deliver these kings, princes, and generals to us, living or dead, and to receive these troops among children of the State. Soon we shall see their numerous legions, running with weapons and equipment under the flags of freedom, and France shall be delivered from her enemies forever.

The fate that awaits her is less consoling for the friends of the patrie, but the fate that awaits her enemies will be terrible.

At the first shot of the canon fired on the frontier, the departments agree on a plan to reduce the castles and the gardens to ashes and to slit the throats of all public enemies who can be found in cities and in the countryside. As the army will massacre its own perfidious chiefs and conspiratorial generals, and as the entire nation will rise up against its own worthless representatives to seize back the powers that they have stripped from her, the mysterious veil long hung over the intrigues of the cabinets will be torn: however impatient the cabinets are to put the French back into chains, I strongly doubt that Louis XVI shall have the humour to do nothing if he even takes a look at this terrible picture. Let some good man have the courage to put it before his eyes.

---------------------------

Notes in the original:

[1] It is an unchanging fact that sieur de Grave, despite all his civic affectations, has not given a single order to prompt the ministry to arm the national guards of the frontiers since he arrived at the ministry. It is upon their actions, and not upon their talk, that the royal agents must be judged.

[2] It was to prevent the citizen battalions from training for grand manoeuvres that the generals have kept them divided and dispersed into different posts.

Translator's notes:

*This would be Mathieu Dumas (1753 - 1837), a colonel of the general staff of Paris, long lambasted by Marat for refusing to fight, and whose name had come from his father, and not to be confused with Thomas-Alexandre Dumas (1762 - 1806) the Haitian general, whose name had come from his mother, an enslaved and nigh-erased woman.

⁑ This would be Jean-François Delacroix (1753 - 1794) the Dantonist, not to be confused with Charles-François Delacroix (1741 - 1805) the Thermidorian, and father to the painter Eugène Delacroix (1798 - 1863).

⁂ Marat notably did not mention either of the brothers of Louis XVI, because the comte de Provence (future Louis XVIII) emigrated in June 1791 to the Austrian Netherlands, and the comte d’Artois (future Charles X) emigrated even earlier, on 17th July 1789 to Savoy.

I am indebted to @citizen-card for helping me with finding out about the relation between Motier and Noailles, and to @lamarseillasie for making me interested on "just what was Marat's view on dictatorship" in the first place.

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Uhm...Marat turn..Turn around

158 notes

·

View notes

Text

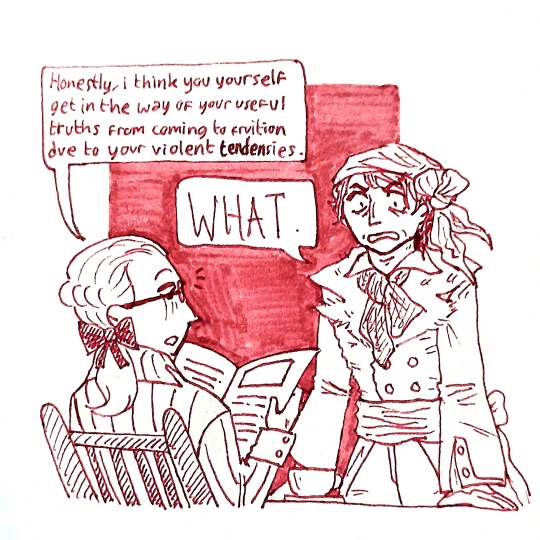

Click for better quality!!!

Marat and Robespierre's very awkward lunch date. A drawing requested by good citizen, @maratsbathtub !!!!!!!!!

jfjadjsjdksk this was really fun to draw

Have a good evening everyone

#tea art 🎨#marat#robespierre#maximilien robespierre#jean paul marat#frev#frev community#french revolution#oklo makes a post

173 notes

·

View notes

Text

When I'm having a crappy day at work, I sometimes visit "L'Ami du Peuple" during my lunch break. It tends to put all the petty day-to-day stuff into perspective…

During the quieter moments, like today, when room 55 is nearly empty, I can't help but notice a pattern. Every single visitor, upon entering, pauses before the painting.

They do a double-take at the painting's name and give him another look. Some snap a photo they'll probably never look at again.

Then they move on.

Most of them likely have no clue who he is. They don't know he's holding a note from his assassin. If they even notice "L'An Deux" written at the bottom, they're probably confused by it.

But still, for those 30 seconds, David's brushstrokes exquisitely forming the face of this stricken man make them pause. What makes them linger? Is it the vaguely familiar name? The face they've seen on numerous posters and leaflets? The unsettling quiet brutality of the piece?

It doesn’t really matter why. Because, for that half-minute, through their eyes, he exists. He is present. He is contemporary.

#pseudo-philosophical ramblings#frev#french revolution#marat#jean paul marat#l'ami du people#jacques louis david#my happy place is a picture of a 18th century dead guy#personal opinion

86 notes

·

View notes

Text

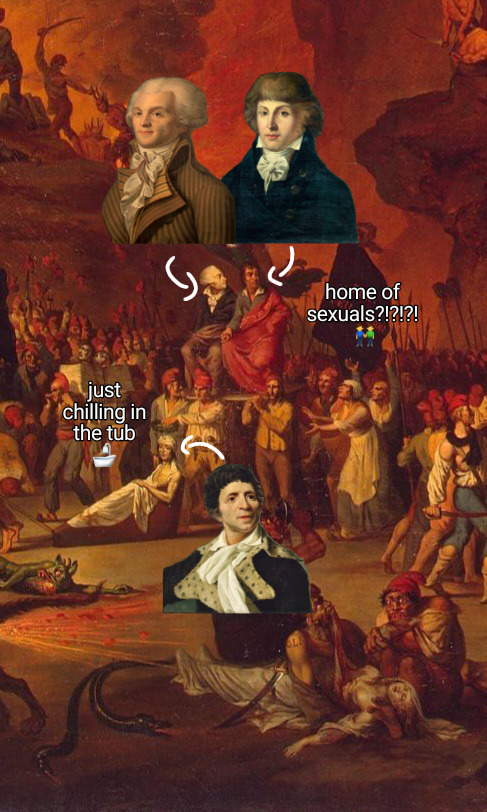

Ummmmmmm ommggg MARAT and Robespierre too 😳

Yesss it’s him! Omg there’s not enough Marat content here. I coloured the blood blue cus I dunno if it’s too scaryyy or not

Anyways, love y’all! 😚

182 notes

·

View notes

Text

#robespierre#frev#saint just#marat#french revolution#maximillian robespierre#jean paul marat#frev memes#louis antoine de saint just

97 notes

·

View notes

Text

the whiplash of reading through l'ami du peuple and seeing marat complain about how the government is using its budget for ceremonial bullshit instead of attending to public needs and then remembering how the government reacted to marat's death... he really was worth more to them as a symbol than as a living critic.

#simone evrard mentioned smth similar iirc#about how people were saying all kinds of shit in marat's name#when it wasn't stuff he supported#marat#jean paul marat#french revolution#frev#pigeon.txt#reading through adp has been very interesting tho#I've been going in order in the original french#good practice for french + cool primary source

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

Since today is Simonne Évrard's birthday I thought it was nice to share my translation of her biography written by the historian Stefania di Pasquale. The books also talks about Simonne's husband, Jean-Paul Marat and sister-in-law, Albertine Marat.

You can find it here.

This is my first ever serious translation work and I'm no professional, so if you notice some mistakes, let me know and I'll fix them ^_^

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marat 🐀

162 notes

·

View notes

Note

hi there!! i was wondering you knew anything about the relationship between robespierre and marat? ive been seeing some information that robespierre wasnt fond (or at least less fond??) of marat than marat was of robespierre, but havent found any other information about it unfortunately. thanks :)!

In total, Marat mentions Robespierre around 90 times in his journals from his debut in September 1789 up until his death in July four years later. The first time he does so (which also happens to be the first connection I’ve been able to find between the two) is already in the second number of l’Ami du Peuple(released September 13 1789) where he writes about a certain ”Robertpierre.” Then one day later, in number 4, he instead mentions a ”Robers-Pierre.” In both these instances, Marat does however appear to just give the exact same summary as three other journals, and there’s value put into it whatsoever.

It would appear Marat never got a hold on how to spell Robespierre’s name properly, as he throughout the rest of his career as a journalist inconsistently shifts between calling him ”Robespierre,” ”Roberspierre” and, in some rare instances, ”Robertspierre.” The next time he mentions him is in number 81 (December 29 1789). The following three times Robespierre is brought up in l’Ami du Peuple are the very first instances of Marat showing his own thoughts on him instead of just giving a neutral summary of things he’s said at the National Assembly:

M. de Robespierre and especially Mr. Charles de Lameth energetically fought against the inconsiderate proposal to give praise to officers, whose conduct has harmed the liberty and security of citizens.

l’Ami du Peuple, number 101 (January 18 1790)

M. de Robespierre supports the motion of Mr. de la Salcette, with more or less solid arguments.

l’Ami du Peuple, number 104 (January 21 1790)

…to remove from the fatherland its most zealous defenders, [the Municipal Research Committee] pushed its audacity to the point of directing its pursuits against Barnavre, Péthion [sic] de Villeneuve, the Lameths, d'Aiguillon, Roberspierre [sic]..., cherished names of the free France, to which it had added those of La Fayette and Mirabeau.

l’Ami du Peuple, number 108 (May 20 1790)

This praising of Robespierre is something Marat would consistently keep up throughout the rest of his journalistic career. Only throughout the rest of 1790, we find him calling him ”the wise Robespierre” (number 156 (July 7), ”the loyal Robespierre” (number 210 (September 3), an orator with ”great principles” and ”excellent views […] [that] we have no doubt he will develop in a way that will cause a sensation.” (number 265 (October 29) and ”[a man] who’s heart always appears to be animated with the purest of civism” (number 320 (December 24), listing him among deputies he considers ”patriotic” (number 156 (July 7), number 188 (August 11), number 210 (September 3), number 277 (November 11), number 288 (November 22), number 292 (November 28) and at one point even playing him on a higher level than so, calling him ”the only deputy who is educated in great principles, and perhaps the only true patriot who sits in the Assembly” (number 263, October 27).

February 2 1791 is the first instance where Robespierre in his turn is recorded to have mentioned Marat’s name. He does so defending the journalist at the Jacobins after an arrest warrant has been issued against him for an article recently published in his paper. Desmoulins’ Révolutions de France et de Brabant, the journal giving the most detailed description of the defence, summarizes it in the following way:

At the same session at the Jacobins, Robespierre, the only member of the National Assembly to whom the severe Marat would not have given the black ball, also took up his defense. He made us aware of the absurdity of the crime that the president of research attributed to the Friend of the People, of getting along with the English. Marat had never ceased to deplore the trade treaty of 1786 with the English, and to vociferate against Pitt, and against the intelligence of the cabinet of S. James, with the Austrian committee of the Tuileries. In favor of Marat was also this thing which militates so strongly for all patriotic writers: if the Friend of the People is extreme and angry, at least it is in the direction of the revolution. On what front did the research committee sign this order against him, under the ridiculous pretext of intelligence with the English, while it at the same time leaves Durosoi, as extreme, as bloodthirsty as Marat, in peace, and so many other friends of the king, the nobility and the clergy, who did not even hide their understanding with the Austrians, with all our enemies, and every day invite them with loud cries to come and slaughter the patriots. There is no reply to this reasoning; so Voidel, who saw his condemnation in everyone's eyes, recognized his sin, and promised to withdraw the order and remove the sentence.

In a speech regarding liberty on the press held on May 11 1791, Robespierre also says that ”if it is true that the courage of writers devoted to the cause of justice and humanity is the terror of the intrigue and ambition of men in authority; the laws against the press must become in the hands of the latter a terrible weapon against liberty,” which according to the by publisher inserted footnote is an allusion to the situation of the journalists Desmoulins and, especially, Marat.

Marat in his turn continued his praising of Robespierre throughout the same year. Besides grouping him together with other men considered patriotic (number 342 (January 16), number 371 (February 14), number 382 (February 25), number 392 (March 7), number 455 (May 11), number 519 (July 15), number 526 (August 1), number 562 (September 30) and calling him things such as ”the loyal Robespierre ”(number 367 (February 8), number 478, number 443 (April 29), number 458 (May 14), (June 3), number 488 (June 13), number 520 (July 16), number 521 (July 17) ”the just Robespierre” (number 409 (March 24) and ”the virtuous Robespierre” number 438 (April 21) he also goes further in placing Robespierre on a higher level than his fellow representatives, frequently going so far as to call him ”the only pure member of the Assembly” (number 414 (March 29), number 462 (May 18), number 472 (28 maj), number 475, May 31, number 504 (June 28), number 510 (July 4), number 511 (July 5). He also starts to frequently refer to Robespierre as ”the Incorruptible”number 458 (May 14), (number 462 (May 18), number 504 (June 28), number 514 (July 8), number 513 (July 13), number 545(September 4), number 551 (September 10) In his Robespierre biography (2014), Hervé Leuwers writesthat, if it was Fréron who coined the nickname, Marat nevertheless did a lot to popularize it. Finally, his number 515 (July 9) Marat dedicates entirely to the ”superb speech” held by Robespierre regarding the flight to Varennes two weeks earlier. His admiration did not go unnoticed by other journalists besides Desmoulins, such as those behind Les Sabbats jacobites, who on April 10 1791 called Robespierre ”the hero of Marat” and those behind Journal générale de France who called him ”the god of Marat, Garat, Carra, Corsas and Marte” on June 13 the same year.

Once Robespierre on September 30 ceases to be a member of the National Assembly, the apperences of his name in l’Ami du peuple do however rapidly decrease, only appearing two more times (number 603 (November 19), number 618, December 6) until Marat temporarily puts it down on December 15.

The first actual meeting between Marat and Robespierre didn’t take place until January 1792, as revealed by the latter ten months later. By then, the two almost lived neighbors since about a month back, Marat having gone to live with the Evrard sisters on 243 rue Saint-Honoré in Decenber, not far from the Duplay house on number 366 on the same street.

One of the most terrible reproaches that people have aimed against me, I do not hide it, is the name of Marat. I will therefore begin by telling you frankly what my contacts with him have looked like. I could even make my profession of faith on his behalf, but without saying more good or more bad than I think, because I do not know how to translate my thoughts to appeal to general opinion. In January 1792, Marat came to see me. Until then, I had not had any kind of either direct or indirect relationship with him. The conversation turned to public affairs, about which he spoke to me with despair. I told him everything that the patriots, even the most ardent ones, thought of him; namely that he himself had put up an obstacle to the good that could be produced by the useful truths developed in his writings, by persisting in eternally returning to extraordinary and violent proposals (such as that of making five to six hundred guilty heads fall), which revolted the friends of liberty as much as the supporters of the aristocracy. He defended his opinion; I persisted in mine, and I must admit that he found my political views so narrow that some time later, when he had resumed his journal, which had been abandoned by him for some time, reporting on the conversation of which I have just described speaking, he wrote in full that he had left me, perfectly convinced that I had neither the views nor the audacity of a statesman; and if Marat's criticisms could be titles of favor, I could still place before your eyes some of his sheets, published six weeks before the last revolution, in which he accused me of feuillantism, because I, in a periodical work, did not say out loud that the constitution had to be overthrown. After this first and only visit from Marat, I found him again at the National Assembly.

In number 648 (May 18) of l’Ami du Peuple, Marat gives his own version of this meeting:

I therefore declare that not only does Roberspierre [sic] not have my pen at his disposal, although it has often served to do him justice; but I protest that I have never had any note from him, that I have never had any direct or indirect relationship with him, that I have never even met him but once; also in this instance, our interview served to give rise to ideas and to manifest feelings diametrically opposed to those that Guadet and his clique attribute to me. The first word that Robespierre addressed to me was the reproach of having myself partly destroyed the prodigious influence that my paper had on the revolution by dipping my pen in the blood of the enemies of liberty, by speaking of rope, of daggers, no doubt against my heart, because he liked to convince himself that these were just empty words dictated by circumstances. Learn, I replied to him immediately, that the influence that my paper had on the revolution was not due, as you believe, to these close discussions in which the vices of the fatal decrees prepared by the Constituent Assembly are methodically developed, but to the terrible scandal that it spread among the public, when I unceremoniously tore the veil which covered the eternal plots hatched against public liberty by the enemies of the fatherland, people conspiring with the monarch, the legislators and the main custodians of authority; but to the audacity with which I trampled underfoot every detracting prejudice; but to the outpouring of my soul, to the impulses of my heart; to my violent protests against oppression, to my impetuous outings against the oppressors; to my painful accents; to my cries of indignation, fury and despair against the scoundrels who abused the trust and power of the people to deceive them, rob them, load them with chains and precipitate them into the abyss. Learn that there has never been a decree attacking liberty and that never an official has allowed himself an attack against the weak and the oppressed, without me having hastened to raise the people against these unworthy prevaricators. The cries of alarm and fury that you take for empty words were the naive expression with which my heart was agitated; learn that if I had been able to count on the people of the capital after the horrible decree against the garrison of Nancy, I would have decimated the barbaric deputies who had issued it. Learn that after the investigation of the Châtelet on the events of October 5 and 6, I would have had the unfair judges of this infamous tribunal perished at the stake. Learn that after the massacre on the Champ-de-Mars, had I found two thousand men animated by the feelings which tore me apart, I would have gone at their head to stab the general in the middle of his battalions of brigands, to burn the despot in his palace and impale our atrocious representatives on their seats as I declared to them at the time. Robespierre listened to me with fear, he turned pale, and remained silent for some time. This interview confirmed for me the opinion that I had always had [sic] of him: that he combined with the knowledge of a wise senator the integrity of a truly good man and the zeal of a true patriot, but that he also lacked the views and audacity of a true statesman.

In 1793, Jacques Roux also claimed to have gone home to Marat the year before and there have received ”a letter for Robespierre and for Chabot, the goal of which was to interest the Jacobin club to propagate an edition of your works.” I can however find no letter from Marat to Robespierre in the latter’s correspondence, nor even a letter to or from Robespierre that so much as mentions Marat (and the same thing goes for Marat’s correspondence). So did Robespierre actually receive this letter, we might assume he didn’t think all that much about it.

Despite Robespierre’s frosty attitude, Marat continued to hold admiration for him when he started up his journal again on April 12 1792, dedicating almost all of number 648 (May 3) and number 660 (May 29) with defending him against girondin attacks, a struggle which he describes as existing ”between the traitor Brissot and the Incorruptible Robespierre” (number 643 April 28 1792).

On September 9, Robespierre held a speech which he ended by recommending voting for Marat and Legendre for the National Convention (he did however deny that be had singled out Marat ”any more particularly than the courageous writers who had fought or suffered for the cause of the revolution” two months later). On September 21 1792, the day after the opening of said Convention, the last number of l’Ami du peuple appears, and a few days later Marat starts a new journal — Journal de la République française (it changed name to Le Publiciste de la République française in March 1793) that would run up until his death in July the following year. In total, Robespierre’s name gets mentioned around 35 times in this journal. As far as I can see, Marat does however appear to have cooled down a bit with his praising, mostly mentioning Robespierre in the context of reciting something he’s said or at tops mentioning him alongside other ”patriotic” deputies. In number 239, released the day before his death, Marat inserts a letter to Robespierre from a certain Labenette, ”orator of the people.”

The fact that Robespierre and Marat didn’t have any contacts with one another was not something that was believed by all contemporaries. Already in 1791, the journal Le Défenseur du Peuple had describedthe former as ”the friend of Marat, who he pretends to doesn’t know.” These allegations got a lot more serious in the fall of 1792, with the two plus Danton being accused of wanting to form a triumvirate, or having arranged the September Massacres together. On September 25 Marat openly denied that any of these allegations aligned with reality, that he had discussed the idea if a dictatorship or triumvirate with Danton and Robespierre, but that both had rejected it:

Certain members of the Paris deputation are accused of aspiring to dictatorship, to triumvirate, to tribunate; This absurd indictment can only find supporters because I am part of this deputation: well! monsieurs, I owe it to justice to declare that my colleagues, notably Danton and Robespierre, constantly rejected any idea of dictatorship, triumvirate and tribunate, when I put it forward; I even had to break several lances with them on this subject.

The very same day, Robespierre made allusions to Marat when regretfully declaring ”it was then that the thoughtless phrases of an exaggerated patriot or the signs of confidence he gave to men whose incorruptibility he had experienced for three years were attributed to us as crimes.”

On October 19 appeared the first number of Lettres de Maximilien Robespierre, membre de la Convention nationale de France, à ses commettants. In number 6, when discussing Marat getting interupted when laying out some own theories on the battalions of Mauconseil to the point that the Jacobins have to move with the agenda due to the tumult, Robespierre writes: ”Whatever the deviations of Marat's imagination, good citizens nonetheless groaned to see personal sentiments make the interests of immocence and oppressed patriotism forgotten, and hateful passions banished from the sanctuary of the laws. dignity, calm and love of humanity.” In number 9 he also writes that ”in his wanderings, Marat often encountered the truth.”

Robespierre also mentioned Marat when the Lettres in January 1793 got renewed for a second edition, starting already in number 1, where he for long defended himself against the girondin Gensonné linking him and Marat together:

What obstinacy to want me to be someone other than myself? It doesn't even matter to you that everyone believes that I named Marat: having been unable to succeed, you have decided to repeat my name so often with his, that I was at least taken for an accessory of this great character, so celebrated in your pages; as if I had not had an existence of my own, several years before you had decided to strip me of it; as if my constituents and my fellow citizens had not been able to judge me by my own actions; while Marat wrote underground, and Brissot still obscurely intrigued, with the henchmen of the old police, his colleagues, and crawled in the antechambers of the men in power. In the past, I still remember, Brissot and a few others had entered into I don't know what conspiracy to make my name almost synonymous with that of Jérôme Pétion; they took so much trouble to put them together. I don't know if it was for love of me or of Pétion: but they seemed to have plotted to send me to immortality, in company with the great Jérôme. I have been ungrateful; and, to punish me, they said: since you don't want to be Pétion, you will be Marat. Well, I declare to you, monsieurs, that I want to be neither. I have the right, I think, to be consulted on this, and you will perhaps not dispose of my being in spite of myself.

It's not that I want to deny Marat the justice that is due to him. In his papers, which are not always models of style or wisdom, he nevertheless stated useful truths, and waged open war against all powerful conspirators, although he may have been wrong about a few individuals. I know that he did not spare you yourselves: but this merit has not erased in my eyes, these extravagant sentences which he sometimes mixed with the healthiest ideas, as if to give to you and to your likes, the pretext of slandering liberty. It was said a long time ago that, in this respect, Marat was the father of the moderates and the feuillans; we could say for the same reason that he is also your boss; and we would be tempted to believe that he only punishes you because he loves you. I bet you love him too, although you pretend to shout very loudly at the slightest correction he gives you. Indeed, what would you be without him? What would become of all your newspapers and all your harangues if he had not written these two or three absurd and bloodthirsty sentences, which you constantly strive to repeat and comment on? You would have perhaps been reduced to becoming patriots, if he had not provided you with the pretext of disguising patriotism as maratism, in order to give to incivism, feuillantism, royalism and rascality, I don't know what air of wisdom and moderation.

It is so convenient for the enemies of liberty to simply appear to be the adversaries of Marat, and to confuse the cause of liberty with the person of an individual, in order to be excused from respecting it. Such was the policy of the first aristocrats, and of the heroes of the intrigue, whose disgraces you will share, after having imitated their exploits. Like them, you want to persuade all of Europe that the Republicans of France, that the partisans of the principles of equality, are only one faction, and that this faction is Marat himself. Thus, thanks to the gift of metamorphoses with which you are eminently endowed, Paris, the Jacobins, the members of the Convention, who do not bend to the views of the intriguers, and Marat are precisely the same thing. All the energetic friends of liberty are, at most, only satellites drawn into the whirlwind of this new star. With this magical name, you claim to overthrow the entire work of our revolution. It is to carry out this great work that you write, that you print, that you speak, that you plot tirelessly: but the revolution will triumph over the name of Marat, as well as over your intrigues; we will do justice to you and to him, by disproving his deviations and by disconcerting your plots. A journalist's sentences have never made a guilty head roll; but the plots of ambition that you seem to forget have caused torrents of human blood to flow. The crimes of tyranny cost humanity more disasters than the most heroic periods of the most atrocious writer. Only you, gentlemen, can give importance to an exaggerated man, much less through your declamations than through your conduct. It would not even be noticed under a wise government. It is only oppression that forces the people to pay less attention to faults that they themselves do not believe, than to the courage of those who unmask their enemies.

He defends himself against the charge of him and Marat being the leaders of a coalition, ”when these deputies, too independent to form a coalition, even with a view to the public good, see every day the coalition of factions.” again in number 3. In number 9, the second to last number, he rhetorically asks whether ”giving ridiculous importance to some inconsistent and bizarre journalist, to charge him with all the iniquities of Israel, and to identify with him all the defenders of freedom?” really is such a good way to ensure tranquility.

Between December 1792 up until the death of Marat, we find him and Robespierre taking part in the same debates at both the Convention and the Jacobin club, sometimes agreeing (December 26, February 21) and sometimes disagreeing (December 16, March 3, June 18) with each another.

On January 4 Robespierre complains that a speech made by Barère regarding the fate of Louis XVI ”contains the most violent diatribes against the patriots” for having stated ”If anything could have made me change my mind [on an appeal to the people], it would be to see the same opinion shared by a man whom I cannot bring myself to name (Marat), but who is known for his bloodthirsty opinions...” A month later, February 11, Marat and Robespierre together calmed down a group of petitioners, disgruntled over not having received a hearing at the Convention. When a representative on February 26 asked ”that Marat be temporarily expelled from the Assembly and be locked up so that it could be examined whether he was crazy” and another one ordered the referral of the denunciation to the ordinary courts, ”Robespierre approaches the president, and there he announces that if the decree passes, Paris will be burning today.”

On 12 April Robespierre spoke against the arrest order issued against Marat the very same day — ”One has requested a decree of accusation be drawn up against the warmest patriots […] Marat spoke with force, precision, and at the same time with moderation. He painted the crimes of our enemies with colors capable of making any man who has any sense of modesty blush.…”

When the indictment against Marat was presented on April 13, Robespierre took to the floor a total of three times to speak against it:

To the question that agitates us, we will not disagree that the man in question excites very strong passions; you are asked if you will decree a representative of the people immediately, or if you will postpone until Wednesday; there is no respect there for the principles, and for what we owe to the character of representative of the people: what, you would send a slanderous report, when nothing is proven, and is it not barbaric to put a representative under accusation without examination; this report is the fruit of passions and liberticidal conspiracies. […]

Yes, it will be proven that this man, whom I have always seen as patriotic, was only attacked to prove that all the Republicans in this Assembly are exaggerated and must suffer the same fate.

…As I see in this whole affair only the developed spirit of the Feuillants, the moderates and all the cowardly assassins of liberty, only a vile intrigue hatched to dishonor patriotism, the departments infested for a long time with the liberticidal writings of royalists, I reject with contempt the proposed decree of accusation.

Marat was acquitted on April 24, and four days later, a motion proposed by him with an amendment from Robespierre was passed at the Jacobin Club.

One day after the murder of Marat, July 14 1793, Robespierre spoke against the idea of granting him a state funeral, arguing that there were much more urgent things that needed to be taken care of before that could happen:

Robespierre: I have little to say to the Society. I would not even have asked to speak had the right to do so not somehow devolved to me at this moment; if I did not foresee that the honors of the dagger are also reserved for me, that priority has only been determined by chance, and that my fall is fast approaching. When a man, deeply sensitive and imbued with a love of the public good, sees his enemies raise their heads with impunity, and already share the spoils of the State, and his friends, on the contrary, frightened by oppression, flee a murderous soil and abandon it to fate, he becomes insensitive to everything, and no longer sees in the tomb anything other than a safe and precious asylum reserved by Providence for virtue. I believed that a session which followed the murder of one of the most zealous defenders of the fatherland, would be entirely occupied with the means of avenging him by serving said fatherland better than before. We haven't talked about it, and what are you occupying yourselves with in this precious time, for the use of which we are accountable? We are dealing with outrageous hyperboles, ridiculous and meaningless figures, which do not provide a remedy to the thing at hand and prevent it from being found. For example, you are seriously asked to discuss the fortune of Marat. Well! What does the fortune of one of its founders matter to the Republic? Is it a memoir that we are going to occupy ourselves with, when it is still a question of fighting for it? One is speaking of the honors of the Pantheon. And what are these honors? Who are those who lie there? With the exception of Le Peletier, I can’t see a single virtuous man there. Is it next to Mirabeau we will place Marat? Next to this intriguing man whose means were always criminal; this man who only earned his reputation through profound villainy? Here we have are the honors requested for the Friend of the People.

Bentabole: Yes, and he will obtain them in spite of those who are jealous of him.

Robespierre: Let us occupy ourselves with the measures which can still save our fatherland; let's make the effect of Pitt's guineas null. Let's bring the Cobourg and the Brunswick back to their territories. It is not today that we must show the people the spectacle of a funeral ceremony, but when finally victorious, the strengthened Republic will allow us to take care of its defenders; all of France will then ask for it and you will undoubtedly grant Marat the honors that his virtue deserves, that his memory demands. Do you know what impression the spectacle of funeral ceremonies attaches to the human heart! They make the people believe that the friends of liberty are thereby compensating themselves for the loss they have caused, and that from then on they are no longer required to avenge it; satisfied with having honored the virtuous man, this desire to avenge him dies in their hearts, and indifference succeeds enthusiasm and his memory runs the risk of oblivion. Let us not stop seeing what can still save us. The assassins of Marat and Peletier must come and atone on the Place de la Révolution for the atrocious crime of which they are guilty. It is necessary that the perpetrators of tyranny, the unfaithful representatives of the people, those who display the banner of revolt, who are convinced that they are sharpening the daggers on their heads every day, of having murdered the fatherland and a few of its members; it is necessary, I say, that the blood of these monsters responds to us and avenges us for that of our brothers which flowed for liberty, and which they shed with such barbarity. We must share the most painful burdens of the State; one must instruct all the people and gently lead them back to their duties; the other must render them exact justice: one must make food flow everywhere; the other deals exclusively with agriculture and the means of multiplying its relations; another must make wise laws; someone else must raise a revolutionary army, exercise and harden it, and know how to guide it in battle. Each of us must, forgetting ourselves at least for a while, embrace the Republic and devote ourselves unreservedly to its interests. The municipality must rule out, for the moment, a funeral celebration, which at first seemed dear to our hearts, but whose effects, as I have demonstrated, can become disastrous.

The following day, July 15, Robespierre asked that Marat’s printing presses be obtained by the Jacobins, a request a different member had already made the day before. A week later, July 22, the club tasked Robespierre, Desmoulins, Dufourny and Le Peletier’s brother with writing an adress to the French people about the murder. Said adress was printed and read aloud at the club four days later, obviously deploring of the event and praising Marat.

On August 5, Robespierre denounced Jacques Roux and Jean Théophile Victor Leclerc as ”two men paid by the enemies of the people, two men that Marat denounced [that] have succedeed, or think they have succeeded this patriot writer.” Three days later, August 8, Simonne Evrard, ”the widow Marat” presented herself before the Convention and held a long speech defending her dead fiancé’s memory, that in her view had gotten hijacked by ”scroundel writers” and in particular the two men already denounced by Robespierre. After her speech was finished, Robespierre again took to the floor to demand that the speech be printed and ”that the Committee of General Security be required to examine the conduct of the two mercenary writers denounced to it; the memory of Marat must be defended by the Convention and by all patriots.” Indeed, Roux and Leclerc would soon thereafter find themselves imprisoned, the former in September 1793, the latter in April 1794. How much of this was Robespierre being genueinly concerned for Marat’s memory and how much it was him using said memory to rid himself of a political rival I will leave unsaid…

On November 23, when Robespierre gives clarifications regarding the CPS changing the general in charge of the taking of Toulon, he says that it was on the recommendation of Marat that the new general had been promoted to rank of brigade leader. ”Marat could have been wrong, but his recommendation was a very favorable presumption in favor of an individual; he has always justified it since.” On 10 January 1794 he exclaims that ”my dictatorship is that of Le Peletier, of Marat. Or I don’t mean that, I don't want to say that I resemble them: I'm neither Marat nor Pelletier; I am not yet a martyr of the Revolution; I have the same dictatorship as them, that is to say the daggers of tyrants.” In an undelivered speech written shortly thereafter he again describes Marat and Le Pelerier as martyrs and Leclerc and Roux as”mercenary writers, daring to usurp the name of Marat, to desecrate it.”

Finally, on 9 thermidor, we find the following two claims made against Robespierre that involves Marat. (1, 2) I will leave them as they are as it’s very hard to know if they’re legit or not:

Dubois-Crancé: I must pay tribute to the sagacity of Marat: at the time of the judgment of the tyrant Capet, he said to me, speaking of Robespierre: ”You see that rascal? That man is more dangerous for liberty than all the allied despots.”

Collot d’Herbois: I am going to cite a fact which will prove that Robespierre, who for some time spoke only of Marat, always hated this constant friend of the people. At Marat's funeral, Robespierre spoke for a long time on the platform that had been set up in front of the Luxembourg, and the name of Marat did not come out of his mouth once; Can the people believe that a person loves Marat when he angrily declares that he doesn’t want to be assimilated to him? No, although these hypocrites talked incessantly about Marat and Challier, they loved neither of the two.

Alphonse Esquiros, who tracked down Marat’s younger sister Albertine for an interview in the 1830s or 1840s, reported that it was ”with bitterness” she spoke of Robespierre. ”There was nothing in common, she added, between him and Marat. Had my brother lived, the heads of Danton and Camille Desmoulins would not have fallen.”

Robespierre’s little sister Charlotte (who Albertine despised) did in her turn write the following regarding the relationship in her memoirs (1834). This anecdote is however suspeciously similar to the meeting Marat and Robespierre describe as having happened in January 1792, in which Charlotte impossibly could have taken part, still not having gone to Paris by then:

I have often heard my brother’s name attached to that of Marat, as if the way of thinking, the sympathies, the acts of those two men were the same, as if they had acted in concert. It is thus that the portraits and busts of Voltaire and Rousseau are placed side by side, as if those two great writers had been the best friends in the world when they were alive, while in truth they found each other insufferable. I do not claim to discount Marat’s merit, nor make an attempt on the purity of his devotion and of his intentions. Some have dared to say that he was in the pay of foreigners; but have they not said that of my brother? The field of the absurd is immense and limitless. Have they not said of Maximilien Robespierre that he had asked the young daughter of Louis XVI in marriage? After such an accusation nothing should be surprising anymore; more burlesque and impossible assertions must be expected; it is the nec plus ultra of inanity. To return to Marat, I will dare to affirm that he was not an agent of foreigners, as it has pleased some to say; Marat had felt the infamies of the Ancien Régime and the poverty of the people strongly; his fiery imagination and his irascible temperament had made him an ardent, and too often even imprudent, revolutionary; but his intentions, I repeat, were good. My brother disapproved of his exaggerations and his rages, and believed, as he said many times to me, that the course adopted by Marat was more detrimental than useful to the revolution. One day Marat came to see my brother. This visit surprised us, for, usually, Marat and Robespierre had no rapport. They spoke first of affairs in general, then of the turn the revolution was taking; finally, Marat opened the chapter on revolutionary rigors, and complained of the mildness and the excessive indulgence of the government.

“You are the man whom I esteem perhaps the most in the world,” Marat said to my brother, “but I would esteem you more if you were less moderate in regard to the aristocrats.”

“I will reproach you with the contrary,” my brother replied; “you are compromising the revolution, you make it hated in ceaselessly calling for heads. The scaffold is a terrible means, and always a grievous one; it must be used soberly and only in the grave cases where the fatherland is leaning toward its ruin.”

“I pity you,” said Marat then, “you are not at my level.”

“I would be quite grieved to be at your level,” replied Robespierre.

“You misunderstand me,” returned Marat, “we will never be able to work together.”

“That’s possible,” said Robespierre, “and things will only go the better for it.”

”I regret that we could not come to an understanding,” added Marat, “for you are the purest man in the Convention.”

#robespierre#marat#jean paul marat#maximilen robespierre#frev#frev friendships#ask#unrelated but the relationship between marat’s little sister and fiancée really was the polar opposite to robespierre’s counter parts…

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marat: To work, patriots of the Mountain, there’s not a second to lose.

me 200+ years later: *works on memes*

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

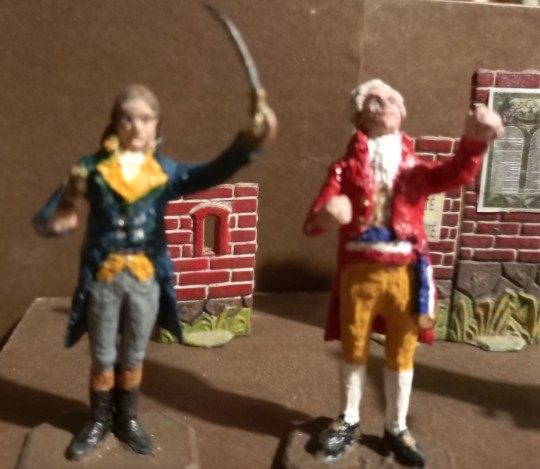

What Ridley Scott did to Napoleon, I did to the heroes of the French Revolution. They are made from Historex multi-pose figures and two-part putty. They couldn't have been uglier 🤦♂️

and there's still a sans-culote, Graccus Babeuf and Hérault de Séchelles (It's going to be the first figure of Hérault in the world! 😄)

#frev#art?? maybe#french revolution#camille desmoulins#danton#jean paul marat#maximilien robespierre#louis antoine saint just

99 notes

·

View notes

Text

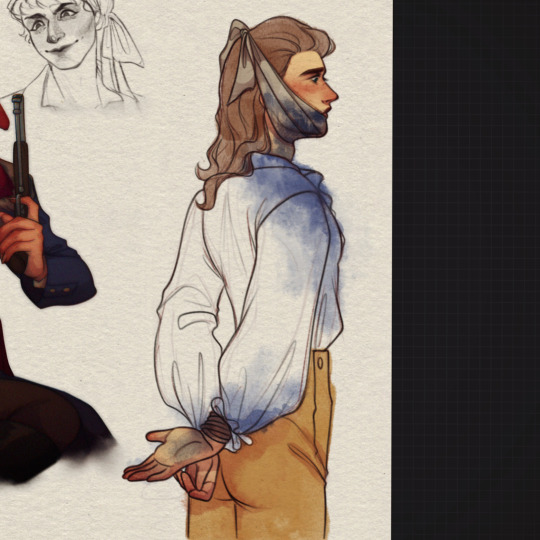

Click for better quality

Help me, my dear friend!

Sooooooo

Because these two have literally been occupying my mind the moment I found out about simonne's existence, I decided to draw them!!!!!!! As one does.

These two together, specifically Simonne, ARE SO UNDERAPPRECIATED

AGHJJHH I WISH WE KNEW MORE ABOUT HER AND MARAT'S LIFE TOGETHER

Well. We know quite a handful of information about them but IT'S NOT ENOUGH FOR ME

Whyyyyyy aren't there more people talking about simonne. She is so awesome. She's extremely politically active, attending the cordeliers club even after marat died, literally funding the publication of his newspapers that would change the hypothetical political tides of France during the revolution and cause big changes for the better, HER DEDICATION TO MARAT IN GENERAL, TO THE POINT OF PROTECTING MARAT'S LIFE FROM LAFAYETTE'S AGENTS MULTIPLE TIMES OVER THE COURSE OF TIME THEY KNEW EACH OTHER, because she truly saw something in him that most people, even to this day, don't see. They understood each other, and not a lot of people can say they understand marat. How she stood by him, even when his chronic illness got worse, and more people were out to get him, their entire relationship is just..... It's just so special to me.

I kind of hate myself more and more by the day because of my chronic illness, aaaand I feel like I'm not worth any dedication from anyone. Because. I feel like i'm just too much to deal with. Too much to take care of. My back pains, constant low energy, and just!!!!!! Never as good as I could be!!!! Aaaahhhh!!!!!! Hahahaha

But the existence of these two. Like. It might sound silly but I feel hopeful knowing they existed. That despite everything horrible that was sent towards marat, despite his illness becoming worse and worse... He was going to be okay at the end, because he had simonne, who was never going to give up on him!!!! Because he was worth the hard work!!!!! And she loved him!!!!!! And he loved her!!!!!! And I won't ever allow anyone to forget them!!!!!! You hear me?!??? Now who wants to be my simonne?!?!!!!?!

#simonne evrard#simone evrard#why are there 2 ways of writing her name????? lmao#marat#jean paul marat#frev#frev community#oh my god i love them so much#MY SWEETIES#THEY ARE DEFINITELY ONE OF MY FAVORITES#tea art 🎨#oklo makes a post

137 notes

·

View notes

Text

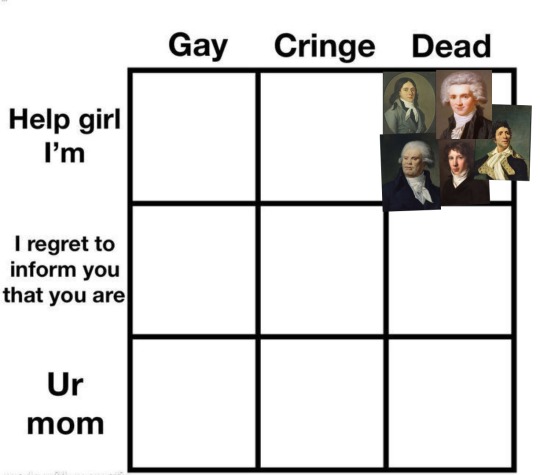

on my shit again

#shitpost#french rev#frev#marat#french revolution#jean paul marat#saint just#maximilien robespierre#danton#desmoulins

179 notes

·

View notes

Text

yeah…

79 notes

·

View notes