#life inside

Text

Inside and Outside: Wolves and Punks

Early-twentieth-century observations of sex between prisoners were shaped by a burgeoning sexological literature whose conceptual categories proved useful in understanding and mapping prison sexual culture. But heightened attention to prison sex in the 1920s and 1930s, on the part of penologists, prison administrators, and prisoners themselves, is not explained simply by the availability of a new conceptual template. While sexologists puzzled over the etiology of same-sex practices performed by apparently "normal" people, those practices would have been more easily and readily comprehended in urban working-class communities of the period.

George Chauncey has documented the visibility of queer life in early-twentieth-century New York City and its integration in working-class and immigrant communities. In that world, Chauncey writes, "the fundamental division of male sexual actors... was not between "heterosexual' and 'homosexual' men, but between conventionally masculine males, who were regarded as men, and effeminate males, known as fairies or pansies, who were regarded as virtual women, or, more precisely, as members of a 'third sex' that combined elements of the male and female.

Prisons were enclosed communities that gave rise to and perpetuated their own distinctive cultures, but they were far from hermetically sealed. The attribution of sexual deviance or "queerness" to the gender transgression of "fairies" and the possibility of conventionally masculine men having sex with them without compromising their status as "normal" found an echo in men's prison populations. Prison vernacular, especially the terms used to denote participants in prison sex, overlapped closely with working-class vernacular and the roles and expectations it delineated, no doubt reflecting its importation into prisons by a disproportionately working-class inmate population and perhaps its exportation into working-class communities as well.

Prison sexual vernacular was part of a prison argot that attracted considerable attention more generally, from both prison insiders and outsiders. Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) organizer and prisoner Hi Simons was fascinated by prison language that seemed to him "full of swagger and laughter, because of the vivid if often violent and vile poetry that streaked through it.... To use it," Simons wrote, "made us feel bold and free." Simons acknowledged that "except for a few terms from the I.W.W. vocabulary," incarcerated labor organizers "added nothing" to the specialized vocabulary of prisoners, but he worked to compile a dictionary of "prison lingo" he learned while an inmate of the U.S. Disciplinary Barracks at Fort Leavenworth and published it in 1933. Others in this period published glossaries of prison terms as well, testifying to the emergence of a collective consciousness and shared culture among prisoners.

Central to prison argot were the coded terms that delineated sexual types and declared expectations about sexual acts and roles, offering a vernacular analog to sexological taxonomies. Noel Ersine included eighteen terms referring to same-sex sex among the fifteen hundred entries in Underworld and Prison Slang, published in 1933. Simons imagined that "a complete prison dictionary" would constitute "an encyclopedia of all imaginable sexual deviations," rivaling the sexologists' ambitions in cata loging sexual variance."

Prison constituted a unique transfer point between expert and vernacular sexual discourses, the terms of one often inflecting the other. Those men typed by sexologists as "pseudo-homosexuals" or "semi-homosexuals" were known to male prisoners as "wolves" and "punks." Those were men whose participation in same-sex sex was presumed to spring not from their nature but from the exigencies of circumstance. Wolves, sometimes also referred to as "jockers," were typically represented as conventionally, often aggressively masculine men who preserved (and according to some accounts, enhanced) that status by assuming the "active," penetrative role in sex with other men. As Victor Nelson made clear, "The wolf (active sodomist)... is not considered by the average inmate to be 'queer' in the sense that the oral copulist... is so considered. " In contrast to many accounts by penologists and some prison officials who blamed fairies for prison seduction, those most familiar with prison life typically credited wolves with initiating sex behind bars.

That initiation was often aggressive. As their name suggested, wolves were understood to be sexual predators, wooing, bribing, and sometimes forcing other men to have sex with them. Wolves were "always on the lookout for a handsome boy with a weak mind, who had nobody to send them in some food and money," sociologist Clifford Shaw wrote in his 1931 case study of a young juvenile delinquent." Berg described the process by which the wolf secured a sexual partner as "a campaign in which all the luxuries of prison - candy tobacco, sweets, and choice foods - are pressed upon the newcomer." Once the object of the wolf's affection accepted the goods offered, "he is quickly given to understand that he must repay the favor in kind." Sometimes seduction by wolves was described as a deliberate and cold-hearted maneuver of engaging a younger inmate in a relationship of indebtedness, which could be repaid only by sex. Others offered examples of more heartfelt and romantic courtship. Nelson recalled "Dreegan," the "champion "wolf" at Auburn Prison," who

outrageously flattered the objects of his lust; he gave them cigarettes, candy, money, or whatever else he possessed which might serve to break down their powers of resistance; and otherwise courted' them exactly as a normal man 'courts a woman. Once the boy had been seduced, if he proved satisfactory, Dreegan would go the whole hog, like a Wall Street broker with a Broadway chorus-girl mistress, and squander all of his possessions on the boy of the moment.

Wolves may not have been motivated by "true" homosexuality, in the understanding of contemporaries, but the relationships they forged in prison were often far from casual. Jealous rivalries and violent confrontations among inmates were credited to the passionate feelings of some wolves for their partners. Inmate-author Goat Laven described "brutal fights," some fatal, that arose from sexual jealousies: "It means a kick in the back to steal another man's kid." Louis Berg seconded Laven account. "The unwritten law of the prison forbids any 'wolf" to make approaches to another's 'boy friend' once he is wooed and won," Berg observed. "But it is not to be expected that men who break the laws for lesser urges will hesitate when they are driven by passions that rock them to the roots of their being. Fights occur between 'wolves' over some boy which are sanguinary and even end in murder."

Berg went on to recount the murder of "Mildred," an inmate at Welfare Island, by her jealous ex-lover. "From all accounts, Berg observed, "Mildred' was the victim of jealousy caused by 'her' unfaithfulness. That 'she' paid with 'her' life partner. shows the seriousness with which such prison marriages' are regarded." To some, the jealous violence that prison relationships could spark testified not only to depth of feeling but also to their similarity to heterosexual relationships. In a disturbing comparison, Berg concluded that Mildred's murder "proves how completely such relationships are identified with the normal ones between men and women." Charles Ford described jealousies among female inmates that resulted in fist fights, "hair pullings," and "every other conceivable type of trouble making activity" and that were even more real than husband-wife jealousies."

One theory explaining the existence of prison wolves, enshrined in inmate lore by the early twentieth century, proposed that "a 'wolf' is an ex-punk looking for revenge!" The object of wolves' and jocker attentions were known as "punks" and "kids," often identified as younger inmates, unfamiliar with life behind bars and unable or unwilling to defend themselves physically. A type recognized in prison argot at least the early twentieth century, punks were understood to be "normal" men, vulnerable to sexual coercion by other inmates because of the combination of small physical stature, youth, boyish attractiveness, and lack of institutional savvy. A few accounts suggested that punks were potential homosexuals whose latent desires were nurtured and realized the prison context, but most saw them simply as the unfortunate victims of wolves.

The punk's fate was often attributed to naïveté and, especially, his ignorance of the inmate code and the consequences of indebtedness. Charles Wharton wrote in his 1932 prison account of a fellow inmate, "a mere boy" who "seemed to have come direct from a farm" who had "all the bewilderment of a child thrust into strange, frightening surroundings." The youth soon became the object of "pretended interest and sympathy" from other convicts, who showered him with presents, "silk hose, fancy underwear, food stolen from the kitchen, and best of all, cigarets [sic], the gold standard of prison barter." In the process, Wharton wrote, the boy "became a wretched victim of the most vicious circle in Leavenworth's convict population.

Punks also suffered as a result of their youthful good looks. Jim Tully, author of the many books on his experiences on the road as a hobo and time in prison, recalled Eddie, a young inmate "with yellow hair and wondering hazel eyes" who was "too beautiful to be a boy." Eddie's life in prison as a result "was made a constant hardship by sex-starved men." Berg wrote that prison populations always include "boys at that uncertain age where they have a good deal of the feminine in them." Such boys, Berg wrote, "are in most prized in jails and prisons as virgins." Berg also attributed the fate of punks to "biologic inadequacy (another name for lack of guts)."

Whether understood to be the victims of their own attractiveness, their youth and small stature, or their cowardice, punks were never depicted as wholly willing participants in sex with other men. Although there was little attention to overt sexual violence in early-twentieth-century prison writing, many acknowledged that some form of coercion was often involved in sex in prison, in men's prisons especially. Like wolves, punks were also understood under the rubric of "acquired" homosexuality - they participated in sex with other men not because of a constitutional condition but because of the unusual circumstances of prison life. "Had they never gone to prison," Berg wrote ruefully, "most of them would today be normal men."

Prison sexual vernacular and the culture it delineated overlapped particularly closely with that of itinerant laborers, tramps, and hoboes who traveled the country's highways, rural byways, and railroad arteries in the early decades of the twentieth century. The association between tramping and homosexuality was strong enough by 1939 for a textbook on prison psychiatry to warn of "the possibility of homosexuality in prisoners of the vagabond type," since "this tendency among them appears to be very widespread." In his 1923 study The Hobo, sociologist Nels Anderson characterized homosexual practices among homeless men as "widespread and described relationships between older men, known as wolves or jockers, with younger men, referred to as punks, kids, or "prushuns." In transient communities, young men partnered with older, more experienced men who promised to protect them and teach them how to survive life on the road in return for domestic and sometimes sexual favors.

Judging from many accounts, those relationships were often predatory and abusive. Jim Tully, whose experiences as a "road-kid," hobo, circus worker, prisoner, and professional prize-fighter provided the material exper for his twenty-six books, characterized the jocker as "a hobo who took a weak boy and made him a sort of slave to beg and run errands and steal for him." Punks, he reported, "were loaned, traded, and even sold to other tramps." John Good recalled that the "criminal tramps or yeggs" who were his companions on the road in turn-of-the-century Denver "needed a boy to beg and steal for them, and to listen around for information." "These boys are degraded to unnatural uses," Good reported, "as well as trained in the arts of pickpocketing and sneak-thieving." Josiah Flynt, an early participant-observer of transient life, also described relationships between boys and their jockers, in which "abnormally masculine" men take "uncommonly feminine" boys as partners." Those attachments sometimes lasted for years, and boys remained with their jockers until they were "emancipated."

Men who lived on the road and on the economic margins were vulnerable to arrest, and incarceration in jails and prisons was a nearly inevitable experience for hobos, tramps, and transient workers. It is not surprising. then, that the vocabulary of prisoners would borrow closely from that of hobo culture, another nearly uniformly single-sex world populated by working-class men. Some prison terms revealed a direct etymology between hobo and prison terminology. When Jack London was arrested for vagrancy in Niagara Falls in 1894, he was locked up in the "Hobo." "The Hobo," he explained, "is that part of a prison where the minor offenders are confined together in a large iron cage. Since hoboes constitute the principle division of the minor offenders, the aforesaid iron cage is called the Hobo." Hi Simons defined the term "Bo" as both a "hobo" and "boy, catamite" in his dictionary of prison argot. The direction of influence was probably two-way, and some prison terms were no doubt ported into hobo and working-class vernacular as well.

The importation of sexual vernacular, customs, and assumptions about same-sex practices from transient men as well as from a larger ur-working-class world meant that some prisoners were familiar with the sexual culture they found behind bars. Fiction writer Chester Himes, who was sentenced to the Ohio State Penitentiary in 1928, claimed "that nothing happened in prison that I had not already encountered in outside life." Himes grew up in a middle-class African American neighborhood in Cleveland, but youthful desire for excitement drew him to the city's rougher side. In prison, he wrote, "all sex gratification derived sodomy, and I had encountered homosexuals galore around the Matic Hotel and the environs of Fifty-Fifth Street and Central Avenue Cleveland." The many incarcerated men with transient pasts would've been similarly familiar with wolf-punk relationships in prison, which mirrored man-kid relationships on the road.

But while prisons, then as now, were by disproportionately populated by working-class inmates, they drew prisoners from other demographic groups as well, some of whom were unfamiliar with prison sexual terminology and the roles and assumptions it described. The persecution of political radicals under the Espionage and Sedition Acts passed during the First World War and in the wake of the Palmer raids of 1919 resulted in the incarceration of activists in the 1920s, many of whom became vocal and articulate critics of the American prison system while behind bars. These spokespeople for the working class often betrayed their own distance from and naïveté about working-class sexual life in their prison writing, and many were shocked by the sexual life they witnessed behind bars.

Alexander Berkman, for example, was candid in detailing his own prison sexual education in a chapter on an encounter with another prisoner, "Red," a hobo who worked alongside Berkman. When Red announced to Berkman, "you're my kid now, see?" Berkman claimed not to understand him and asked him to explain. Bewildered by Berkman's naiveté, Red exclaimed, "You're twenty-two and don't know what a kid is! Green? Well, sir, it would be hard to find an adequate analogy to your inconsistent maturity of mind." When Red explained to him the practice he termed "moonology," which he defined as "the truly Christian science of loving your neighbor, provided he be a nice little boy," Berkman professed not to "believe in this kid love," and was deeply shocked, protesting that "the panegyrics of boy-love are deeply offensive to my instincts. The very thought of the unnatural practice revolts and disgusts me." The pedagogical question-and-answer structure of this chapter allowed Berkman to tutor his readers in "moonology" while maintaining claims to his own sexual innocence. He may also have intended to contrast Red's perverse sexuality with his own presumably platonic love for another inmate that he described later in the memoir. But Berkman was far from alone among early-twentieth-century inmate narrators in professing innocence of same-sex sexuality before life behind bars.

When attorney and former Illinois state congressman Charles S. Wharton was sentenced to two years in Leavenworth penitentiary in 1928 for conspiracy in armed mail robbery, he acknowledged his own pre-prison innocence. Prefacing his discussion of "the worst of all phases of prison life," which he attempted to describe "as delicately as possible," Wharton wrote that, "looking back, I felt that I had been everywhere, seen everything, done about all which the average man-about-town is expected to do, and I held that impression until Leavenworth made me feel like a country yokel staring slack-jawed at his first sight of urban sin."

Socialist and anti war activist Kate Richards O'Hare was similarly shocked and appalled by the homosexuality she witnessed as an inmate of the Missouri state penitentiary in Jefferson City in 1919-20. Scoffing at O'Hare's estimate that 75 percent of her fellow inmates were "abnormal" as "entirely too high," Fishman speculated that she was "naturally led into such an exaggeration because, having no previous personal knowledge of prisons, she was swept off her feet to find that such things existed. She was utterly amazed when I told her that homo-sexuality was a real problem in every prison."

Eugene Debs, who was convicted of violating the Espionage Law in 1918 and sentenced to ten years in prison, lamented that "every prison of which I have any knowledge... reeks with sodomy" and wrote with dismay about "this abominable vice to which many young men fall victims soon after they enter the prison." "I shrink from the loathesome [sic] and repellant task of bringing this hidden horror to light," Debs wrote. "It is a subject so incredibly shocking to me that, but for the charge of recreance that might be brought against me were I to omit it, I would prefer to make no reference to it at all." Debs wrote in near-apocalyptic language about the fate of the boy "schooled in nameless forms of perversions of mind and soul" and prison sexual practices that "wreck the lives of countless thousands and send their wretched victims to premature and dishonored graves."

Whether shocked or inured, prisoners of all stripes acknowledged sex in both men's and women's prison as nearly ubiquitous and its roles and customs elaborated to the point that it constituted a culture unto itself. That culture occupied a curious status in early-twentieth-century prisons. Officially, sex between prisoners was unequivocally forbidden. Prisoners who were found engaging in sex were punished, often by placement in solitary confinement and extension of their sentences. Some prisons took harsh and sometimes draconian measures to distinguish homosexual prisoners from the general population in order to humiliate them and punish their behavior. In the federal penitentiary at Leavenworth, inmates were reportedly forced to wear a large yellow letter D (designating them as "degenerate") if they were discovered having sex.

The superintendent of the Ohio prison at Chillicothe boasted to the director of the Bureau of Prisons, in response to a question about how he handled the problem of "sex perversion" at the institution, that he had found a way to deter such practices through the use of humiliation. "By this I mean that all known perpetrators or anyone anyway connected with sexual perversions be been compelled to sit at a certain table at the mess hall." A report from Kentucky noted that inmates convicted of sexual offenses had one side of their heads shaved to identify them. These practices of marking prisoners as homosexual were forms of punishment for sexual transgression; they also suggested the need for the production of a legible marker of homosexuality that ran counter to the notion that homosexuals, inside and out, were easily identifiable by their gender transgression.

Homosexual prisoners were also dealt physical punishments. A photograph from a Colorado prison depicted two African American prisoners wearing loose dresses, perhaps as another form of stigmatizing market of sexual deviance, and pushing wheelbarrows filled with heavy rocks as a form of punishment for same-sex sex. Kentucky physician F. E. Wylie proposed sterilization and "emasculation" that would "make it impossible for degenerates to commit sex crimes," adding that "surgery might even be used as a punishment" for homosexuality. The authors of an investigation of the Oregon state penitentiary in 1917 moved further to argue that "in cases of congenital homo-sexuality in the penitentiary," the more radical surgery of castration was necessary, to deprive offenders not only of the ability to procreate but of their libido as well. By the 1920s, more than half of the United States had adopted sterilization laws and some targeted "moral degenerates and perverts" specifically. Those laws were most easily and readily applied to people in prisons, mental asylums, and other carceral institutions.

Sex in prison was officially prohibited and sometimes harshly punished. But because of the difficulty of detection and the belief in its inevitability, prison officers often seemed to take it in stride. Joseph Wilson and Michael Pescor criticized prison officers who "regard homosexual practices as only another kind of dirty joke" and wrote that it was "essential that "this question shall always be considered gravely-never with smiles smirks, and a shrug of the shoulder" in their 1939 text on prison psychiatry, suggesting that this was often precisely how it was treated. Berg confirmed that to officials at Welfare Island, "the 'fairies' were, for the most part, simply the butt for lewd jokes. When they spoke of perverts it was with the kind of indulgence that one uses toward children whose peccadillos are amusing rather than serious." He added that "sex indiscretions" were "rarely detected and still less frequently punished."

If prison guards could not be relied on to maintain a properly vigilant and condemnatory attitude regarding prison homosexuality, the some hoped, prisoners themselves would rise to this role. "Only the co-operation of the decent element will ultimately weed them out," Sing Sing warden Lewis Lawes speculated in 1938. Wilson and Pescor went so far as to suggest that if homosexuals "received a reasonable dose of violence" at the hands of prisoners "known to be aggressively heterosexual," it would "help build up a correct prison community attitude towards this question."

But the community attitude in men's prisons, to the extent that it is possible to generalize, seemed often to be characterized by a rough tolerance, even by those who presumably did not participate in same-sex sex. Samuel Roth, who spent several years in prison for publishing what was considered obscene material, noted that "one thing happened immediately," on his incarceration; "I lost my horrors of [homosexuality] as a vice." He was far from alone. Recalling his experience on a Georgia chain gang in the 1930s, George Harsh had "too many other things to think about to care what two consenting adults do between them." "Under the conditions," Harsh wrote, "I think such a situation was inevitable, and I could understand it and condone it." Indeed, the institutional culture of some prisons recognized the established place of prison fairies. Though fairies were segregated in Welfare Island's South Annex, they were allowed to stage a bawdy Christmas show called the "Fag Follies." In later decades, prisons would sponsor football and baseball games that pitted queens against jockers.

- Regina Kunzel, Criminal Intimacy: Prison and the Uneven History of Modern American Sexuality. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008. p. 61-73

#prison slang#convict code#wolves and punks#history of homosexuality#history of heteronormativity#sex in prison#life inside#research quote#reading 2021#hobos#tramps#working class culture#history of crime and punishment#american prison system#victor nelson#chester himes#samuel roth#hi simons#penology#prison administration#queer history

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

shoutout to the mutuals i never talk to. shoutout to the mutuals who i silently reblog stuff from and who silently reblog stuff from me. shoutout to the mutuals who i don't have the balls to reach out to. shoutout to the mutuals i was once close with but now we are merely coexisting. i see you. i appreciate you

10K notes

·

View notes

Text

mike flannagan essentially saying that greed and capitalism and the hunger for money (not borne out of a need for safety and contentment, but for power and the urge for more) is death to an artist. that poetry and truth and art cannot live in tandem with greed. that they are anathema to the duplicitous, treasonous and covetous nature of the wealthy and gluttonous.

#how verna said something about poetry being the vessel for hard truths#and roderick spent his entire life lying and lying and killing the poet inside of him#woof#mike flannagan#the fall of the house of usher#usher spoilers#house of usher

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

you think YOU had a bad day at work?

bonus: sid shrieking "no!!!! NO!!!!!" loud enough to be heard in the stands and on camera

#this is now my FAVOURITE game i've watched in real life knocking the game misconduct one off the number one rank#he was so annoyed the entire game and so annoying about it :')#he kept shrieking away on the bench and i couldn't hear a word from where i was seated#but you could just hear this constant yipping away dhfsgfkjshgfsjf PLEASE it was so funny your 36-year-old babygirl was BARKING#drew kept sitting there like... is mom okay... i don't think mom's okay...#also extremely good for me (since he wasn't really hurt) was the whumpfest of it all oh my god what ancient gods did he anger.........#geno kept Hovering in concern#po kept giving him little shoulder pats the way a sweet brave babyboy would try his best to soothe a rabid little dog#ek of course kept trying to slide right inside him and also kept skating up to him and STARING him in the face in concern/lust/both#also guys this is my first time in canada ever!!!!!!!! i'm excited#anyway. very good game for me sorry for this post but you know i love a#long post#sidney crosby#evgeni malkin#pittsburgh penguins#also!!! to all who celebrate#ramadan kareem/eid mubarak#<333 staying with a friend here through the eid celebration and they've been cooking and everything smells so good

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

experimenting w making little trek dolls for the STLV craft swap :))

#sisko first bc idk how I'm gonna make hair LMAO but isn't he so cute??#made the doll a while ago but I just made his little outfit today and yesterday :))#hopefully giving them away for free means no one will mind the shoddy craftsmanship lmao#I think I've set a new record for terrible hand sewing. and there's raw edges on the inside. and none of the thread is the right color#but WHO CARES HES SO CUTE!!!!#it's the early ds9 uniform bc I've been watching voy and I'm sooo enamored with their uniforms ugh I need to make an actual life size one#watching voyager will have u saying things like. surely it can't be that hard to sew an invisible zipper??#anyways. need to figure out how to make hair so I can make characters other than him and picard 💀💀#ds9#star trek#benjamin sisko#deep space nine#captain sisko#narcissus's echoes#narcissus plays dress up#(?)

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

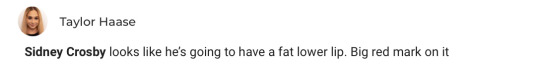

two sides of the same coin

#itadori yuuji#ryomen sukuna#jjk#jujutsu kaisen#my art#jujutsu kaisen fanart#brainrot incoming (pls don’t mind me)#one thing sukuna and yuuji have in common is that they’re both absolutely miserable#sukuna is utterly selfish and yet it only made him hollow inside and now he’s just killing time waiting for death to come#yuuji is completely selfless and yet it’s only made him suffer and bc of that he’s been constantly trying to check out of life#and I think the funniest but also the most painful thing about these two is that…#despite that they’re vastly opposite they might be the only people that can understand each other the most#imagine them having a heart to heart lol maybe then they would realise some things about themselves

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

#Updated!! Cause sooo many people asked for lobcorp and a bunch of others#lobotomy corporation#fallout 4#inside job#scp#portal#half life#control 2019#literally me though

9K notes

·

View notes

Text

I just don’t want to feel anything anymore. I’m tired, drained, exhausted. Just let me die already.

#kinda depressing#depressing shit#this is depressing#bpd#bpd shit#depressing life#sorry for being depressing#tw depressing thoughts#actually bpd#bpd mood#ptsd#trauma#dead inside#mentally fucked

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

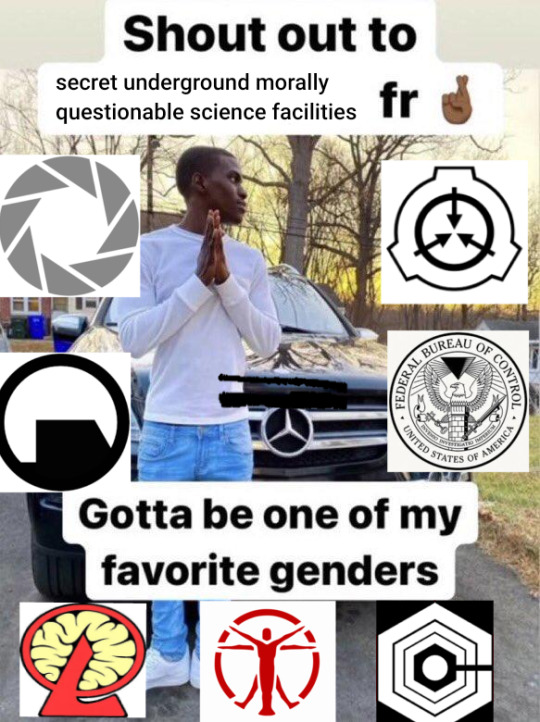

more svanhildr - trying new things, like a brave boy

#my art#anthro#furry#illustration#oc#svanhildr#dysterel#i have so many great brushes i never use for no reason so i'm expanding my horizons and using like 10 brushes instead of 3#and i used the pencil tool for the first time so i could make a sprite of svanhildr#btw don't do pixel art without looking at multiple tutorials first. worst mistake of my life#i think my blobby indeterminate sprite daughter looks great though#also has anyone seen brass eye and if so have you seen when the posh reporter lady is walking to the prison#and she turns to the camera and says something like “i'm going going inside now. like a BAD boy”#anyway it gets me every time and writing brave boy made me remember it

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Progressive-Era Prisons and the Emergence of Prison Sexual Culture

"Fag Follies" and football games would seem to be worlds away from the dens of solitude and enforced silence held as carceral ideals just a few decades before. Changes in prison administration and prison architecture and penology aimed at enhancing inmate sociability in the 1910s and 1920s combined to create new sexual possibilities among prisoners. Material changes in prison architecture and administration that made possible new forms of contact between inmates made sexual contact more likely well, creating new sexual geographies behind bars. Prison writers probably devoted more attention to prison sex in the early twentieth century, at least in part, because there was more sex in prison to attend to.

Beginning in the 1910s, Progressive reformers undertook an ambitious agenda to transform the prison. While few prisons if any had achieved the utopian nineteenth-century goal of perfect carceral solitude, a new generation of prison reformers and administrators judged those earlier visions once inhumane and impractical. Armed with progressive ideas about trinality that emphasized environmental and psychological causes over congenital and moral ones, reformers repudiated nineteenth-century strategies of solitary penitential reflection as well as the disciplinary practices of lockstep marching, the rule of silence, the humiliation of striped uniforms, and corporal punishments such as flogging and the water torture, and the shackling of inmates to cell walls still practiced in many prisons. Embracing a new commitment to correction and rehabilitation, they encouraged inmate sociability, collective labor, exercise, and recreation that, they hoped, might approximate the normal society to which the reformed criminal would return.

The federal penitentiary in Lewisburg, Pennsylvania, opened in 1932, was built with six dormitories rather than cells, with the notion that "the openness promotes rehabilitation by teaching men how to get along with each other. " Some prisons built baseball diamonds and exercise yards and organized football leagues and prison bands, and prisoners in many institutions began to enjoy weekly movie nights. Some reform-minded prison administrators went so far as to give prisoners a role in the government of their own community. A pioneer in the concept of inmate self-government, reformer and warden Thomas Mott Osborne established the Mutual Welfare League in the New York state prisons at Auburn and Sing Sing. Designed to train prisoners in the exercise of democracy, the league was composed of a committee of prisoners elected by their peers and responsible for overseeing prison disciplinary procedures.

Changes in prison architecture and its uses, reflected most centrally in the yard, accompanied and reinforced new ideas about prison life. An iconic feature of the "Big Houses" of the day - Sing Sing, San Quentin, Stateville, and Jackson foremost among them - "the yard" referred typically to an open expanse in the middle of the prison. Often surrounded by imposing and fortified walls and towers, its barbed-wire (and later electrified) borders were closely patrolled by armed guards. The activities within, however, were often considerably less strictly monitored than its perimeters. As "freedom of the yard" was gradually extended, prisoners spent less time by themselves in their cells and more time mingling with each other.

The resulting prison sociability ran directly counter to the Benthamite vision of strict surveillance and perfect discipline, and was captured in the writing of many prisoners. On admission to Utah's state penitentiary, Jack Black explained that he was "turned loose in the yard where there were about one hundred prisoners." There, the prisoners played poker all day in the yard on blankets, and occasionally a game bull, when they could get up enough ambition." Inmate George Wright described the federal penitentiary at Leavenworth in 1915 as "a Jory": "All the prisoners are allowed to roam anywhere inside the walls, you can say run foot races, or anything you like." Edward Bunker told of living "two lives" as an inmate at San Quentin a few decades later in the early 1950s, "one in the cell from 4:30 p.m. to 8:00 am.. the other in the Big Yard." "In those days," Bunker explained, "convicts had the run of the inside of the prison. Each morning when the cell gate opened, I sallied forth to find adventure."

The yard was a place of exercise, organized athletics, and casual congregation. Reformers and administrators hoped that these changes would promote a healthier, more "natural" environment that would help prepare prisoners for life after release. But inmates in early-twentieth-century prisons took advantage of the new blind spots in prison surveillance to engage in a range of illicit as well as licit activities, including drug dealing and consuming, fighting, and sex. "Every day at nine o'clock the cells were opened by the turnkeys, and the men circulated freely in the entire prison block for the rest of the day," African American Communist organizer Angelo Herndon recalled in his 1937 autobiography. "This made it possible for the prisoners with homosexual inclinations to go prowling around for their private pleasures." Prisoner Malcolm Braly recalled a time, before the segregation of homosexuals at San Quentin initiated at the beginning of warden Clinton Duffy's regime in 1941, when "the queens had been free to swish around the yard and carry on open love affairs." The "corner of the yard" was the site of a wedding ceremony between male inmates observed by Piri Thomas, as well as for the wedding ceremonies of inmates of the women's penitentiary at Bedford Hills years later.

The new uses of the yard opened up a place of sexual display and opportunity in many prisons. But a loosely supervised yard could also be a place of sexual vulnerability and danger. "Vast and forbidding when empty," the yard, in prison chaplain Julius Leibert's description, was "a monster when packed. Five thousand heads, ... and a million pent-up hungers aching to burst forth-that's the yard. Perverts on the prowl, jockers' ganging up on a fish, 'queens' reveling in fights between rivals for their favors, homos pairing off for an affair or quarreling like obscene lovers."

The early twentieth century also witnessed the expansion of profit-making prison industries, bringing together prisoners to work in laundries, woodshops, metal shops, forges, mines, quarries, and farms. Collective workshops were much less closely monitored than cellblocks, and the movement of prisoners there, as on the yard, was less carefully regulated. These changes also produced new opportunities, settings, and spaces for encounters between prisoners, some of them sexual. Inmate John Reynolds had earlier warned of the "horrible and revolting practices of the mines" where prisoners labored together side by side in the federal prison at Leavenworth, Kansas. There, "far removed from light and even from the influences of their officers," prisoners were free to "mistreat themselves and sometimes the younger ones that are associated with them in the work." Years later, Ted Ditsworth described his first day working to coal mine as a prisoner in Missouri in the 1920s:

"I had many propositions where these miners would dig my task for me if I would be their kid - was they meant was that they wanted to use me in a homosexual way."

Some of this new inmate sociability and relative freedom from scrutiny was the result of progressive planning, and some was an inevitable consequence of the overcrowding of prisons that had vexed nineteenth-century prison administrators and intensified in the twentieth century. The prison population in the United States more than doubled between 1890 and 1925 and grew even more rapidly from 1920 until World War II, swelling with the rise in unemployment during the Depression. Despite a new commitment to identifying and classifying homosexual, mentally ill, and "hardened" prisoners in order to segregate them from the general population, not all prisons could afford to employ trained psychiatrists or had the physical space to put those plans fully in place.

Overcrowded prisons carried associations of sexual impropriety for early-twentieth-century observers, as they had for their predecessors a century earlier. Louis Berg cited overcrowding as a serious factor contributing to prison homosexuality, writing that "when two or more men are confined in one cell and sex starvation has existed for some time, "doubling up' becomes more than a mere expression to denote cell occupancy. One prisoner described life in the military disciplinary barracks in 1919 as a place where "a man of refined sensibilities is often quartered in the same double-decked bunk with a degenerate or a moral pervert." Investigator Dean Harno wrote to sociologist Ernest W. Burgess in 1927 about the reformatory at Pontiac, Michigan: "All cells have two inmates and quite a number have three. This brings a very acute matter in connection with the morals of the institution." A prisoner of that institution called Pontiac "a 'deformatory'" in 1927, noting of sexual perverts: "They take them fellows and separate them in a separate building so they don't have to mix with the other fellows." Unevenly instituted in prison for men, the practice of segregating homosexuals was virtually unheard of most institutions for women. Kahn noted that, at the Women's Workhouse on Welfare Island, "the homosexuals have been unclassified and are not segregated so that they all mingle freely with the other and are not segregated. "

Prisons varied dramatically by geographical region, and certainly not all prisons put progressive reforms into practice. Many Western state penitentiaries in the early decades of the twentieth century, some resembling hastily built stockades, allowed for little if any classification and segregation of prisoners by offense, sexual disposition, or any other taxonomy. Prisons were peripheral to the criminal justice system that emerged in the South after the Civil War, and some Southern states lacked them altogether. Instead, convict-lease systems flourished in the post-bellum South, drawing heavily on a newly criminalized population of black men and essentially replacing the labor system of slavery. Prisoners in that system were contracted out by the state to work on sugar and cotton plantations, in coal and phosphate mines, turpentine farms, brickyards, quarries, and sawmills, and on levee and railroad construction, where they were exposed to harsh conditions and often brutal treatment. Later in the 1930s, prisoners in the South worked on chain gangs, moving about in labor camps rather than housed in permanent prisons. Mississippi's notorious Parchman penal farm, with its sprawling cotton acreage, predominantly African American field hands, and armed white overseers, resembled an antebellum plantation more closely than it did a modern prison. Constructed in 1904, Parchman served the postbellum imperatives of racial subordination and control and provided as well a cheap and steady labor supply for the rapidly industrializing New South.

Even those prisons furthest removed from Progressive ideals, however, allowed for considerable interaction among prisoners. Convicts leased by railroad companies "slept side by side, shackled together" in mobile iron cells. Collective work and living conditions on prison plantations, in which men worked together by day and slept together in stacked bunks in barracks known as "cages" by night, also allowed for considerable unsupervised contact among inmates, albeit under horrific conditions.

With this increase in inmate interaction and sociability emerged a distinctive and broad-based prison culture that expanded and flourished in the early twentieth century. Prison accounts in this period recognized the development of a prisoners' code of behavior and ethics, the establishment of a tradition of prison tattooing, prison songs and work chants, and the emergence of a comprehensive prison argot. Prison sexual culture was part of this efflorescence of inmate cultural life and increasingly expansive communal life among prisoners.

- Regina Kunzel, Criminal Intimacy: Prison and the Uneven History of Modern American Sexuality. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008. p. 73-75

#penal reform#penal reformers#wolves and punks#history of homosexuality#history of heteronormativity#sex in prison#life inside#academic quote#reading 2021#progressive penology#prison administration#classification and segregation#history of crime and punishment#american prison system#penology#queer history

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#selfie bee#me telling a coworker who I have been working with for 4 months and whose name I do not know about my toenails#i'm sorry Tobias (?? Paul ??) it was the only topic I could come up with after I already told you about the big bird I saw in 8th grade#FRIENDS how are you!! :) how has the new year been so far!!#did you have a lot of snow on christmas!#we did and it was really fun! I had a very bad cold so I just watched the snow from inside but that was good too c:#do you have any plans for the new year?#i always have lot and most of the time I do not do any of them but planning is fun#this year I REALLY want to watch all of Star Trek ヽ(´∇`)ノ#I would also love to learn how to make a handstand#imagine if you could just make yourself upside down#but it is a far away dream because honestly I am not very good at being usual side up most of the time either#but I will try probably at least 2 times to learn it ( ᐛ )#maybe I'll finally finish that website!#new years are good and fun#it's wild to think about how much daily life has changed since last year but I feel just the same :)#who knows what this year will bring!#I hope I don't hit a pheasant with my car#I almost hit a pheasant with my car last year and the pheasant made direct eye contact#I wonder how he is doing today#since that moment I think about pheasants a lot#I knew they were real but I had never seen one#just to know they are out there is a mystical feeling#right know it is raining so all the pheasants might be wet#get dry soon pheasants!!#I don't think I've ever seen a wet bird either#I don't know what do do with all these birds thoughts#also thank you for the person who asked about my skirt!! ( ˊᵕˋ )♡.°⑅#I've finished it and its really really bad#but I love it

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

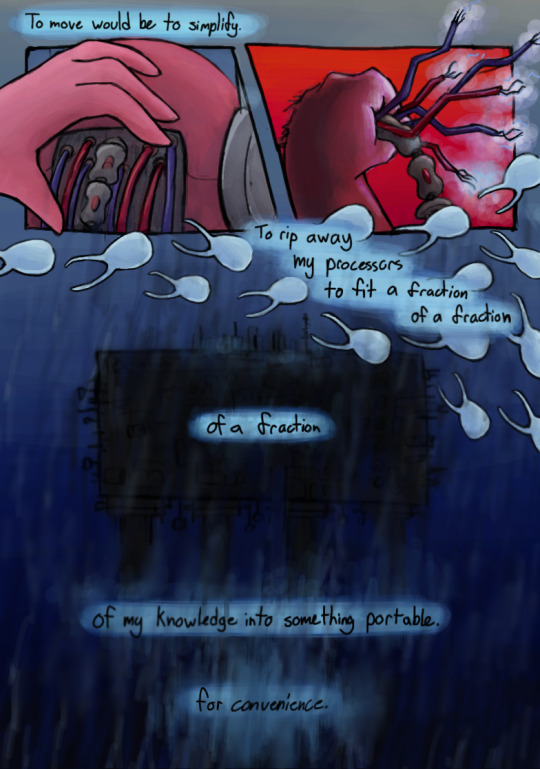

case study of the self-identified god

#obsessed with the fact that rain world is a game about survival#yet every character we meet has the express goal of trying to optimize killing themselves#every creature in game seems perfectly content fulfilling their role in the ecosystem no matter how many cycles they do the same thing#(rly obvious with gourmand's entire route. guy who lives their life to the fullest without the slightest hint of resentment)#it was really only the ancients who thought they were above it and thought of it as something to escape from#5pebbles is so interesting because the only reason hes “”“godlike”“” is because of his vast knowledge. if he was in any slugcats shoes he#would die instantly which is ironically what hes been trying to do this whole time#this comic was kind of exploring the idea of awareness (divinity) as something that drags down ones enjoyment of life (walking).#if 5p would humble himself down enough to walk around like any other creature#he would a) be much happier in life and b) achieve the ascension he's been gunning for for millennia like all the slugcats did#but he never will.#getting rid of all his work on the problem or even his awareness of it entirely#would just be a trick of convenience that steals away his godhood#and him calling himself godlike is kind of a cope LOL#a cope being faced with a problem he was never meant to solve#a cope being faced with what he did to moon#a cope being faced with the rot inside him#oh well.#anyway fuck 5 pebbles i hate that guy#rain world#rain world fanart#rw five pebbles#rain world five pebbles#rw gourmand#rain world gourmand#five pebbles#rain world void worm#rain world ancients#also JUST KIDDING ilu 5p. you suck but i💛u

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy holidays, Law! EAT SNOW

#trafalgar law#luffy#lawlu#tony tony chopper#monkey d. luffy#one piece#op#my art#dingbatsy#fanart#drawing law so tired and dead inside adds years to my life#sorry law#let luffy loosen you up#i really love how choppers expression came out lol

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

The only reality where I'm happy is a reality where I'm dead, gone from this earth.

A reality where I'm never born.

Everything would be so much better.

#personal vent#anxiety depression#depressing life#depressing shit#kinda depressing#dead inside#sorry for being depressing#tw depressing stuff#tw depression#tw depressing thoughts#bpd vent#bpd fp#actually bpd#bpd thoughts#bpd

729 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Systemic Approach (Part Two),” Avengers Unlimited (Vol. 1/2022), Infinity Comic, #64.

Writer: Mat Groom; Penciler and Inker: Caio Majado; Colorist: Pete Pantazis; Letterer: Joe Sabino

#Marvel#Marvel comics#Marvel 616#Avengers Unlimited#Avengers Unlimited Infinity Comic#Moon Knight comics#latest release#Moon Knight#Marc Spector#Jake Lockley#Steven Grant#Captain America#Steve Rogers#hey Mr. Groom excuse me but how did you get access to inside my head because this is pretty much exactly what I could have wanted in life#because don’t get me wrong I love Mr. MacKay’s run but one thing I’ve been missing is just Steven - Jake - and Marc interacting#(and I was hoping that the name of this arc was in reference to the Moon Knight system but I hadn’t dared hope too much)#which means there’s so much I love here#love Jake’s jacket and the acknowledgement that the people he mingles with are in no way lesser than Steven’s socialite#or Marc’s superhero ilk but rather the people who often just need some help (whether that be through Steven’s funds/business acumen#Jake’s hands-on social support#or Marc’s /very/ hands-on support method of boxing villains over the head) but could be the least likely to get it#and !!!!! an acknowledgement that the system is a strength and an invaluable asset to Moon Knight work !!!!#and that it was Khonshu’s influence that was largely the problem as opposed to the system’s neurodivergence !!!!#and an acknowledgement from Cap of all people! I WEEP#it just means so much to me: Marc getting some support both from the system and from Cap#as well as how in character this is for Cap#as some of my favorite moments of his are where he reaches out to those deemed by others too ‘unstable’ or ‘unreliable’ to ever amount to#much in the grand scheme of things and he asks them to be Avengers#recognizing what invaluable talents they posses#could the cynical say this reads like a Saturday morning psa? sure but this is an infinity comic with Cap. Enjoy it for what it is akshsksj

1K notes

·

View notes