#like she wants to expose the racism of colonization by using a book from the colonizer’s perspective which is kinda dumb

Text

I think it’s so funny how every time I read my book for class I fall asleep as if my body can’t tolerate the bullshit I’m reading.

#payton goes to: college#I hate this book so much#I’ve got like half a chapter left and then one more section for Wednesday’s class and I’m done#but then we have to watch the film#I love how my professor didn’t consider choosing a book from a perspective of the negative impacts of colonization and went with this book#like she wants to expose the racism of colonization by using a book from the colonizer’s perspective which is kinda dumb#since the US already promotes that view#she didn’t really get my point and it didn’t feel like it would be meaningful to go in circles with her about it#it’s so strange because the books we read for women and gender studies were so good and these ones aren’t I guess her concussion did her in

1 note

·

View note

Photo

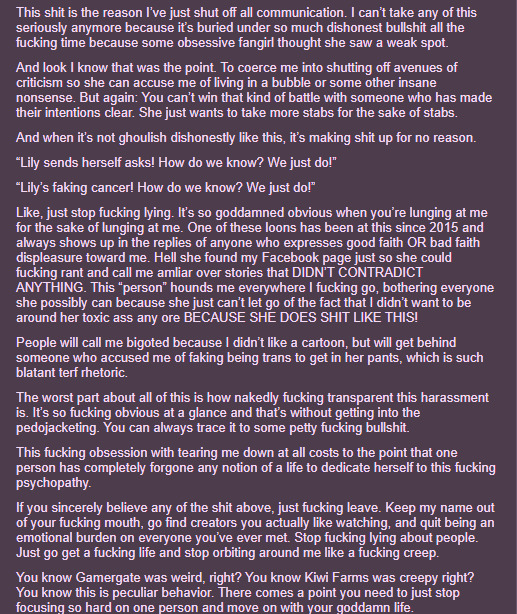

...This post really is the definition off, “Writing your version of events and expecting everyone to believe them.”...which given how dedicated parts of Lily’s fanbase can be, will happen, but just...let’s see:

The whole thing with Rebecca Sugar is not only because of how Lily acted when being critical of the show, but also cause of how even in 2023, Lily still has an ongoing hatred for Rebecca simply cause Lily didn’t like Rebecca’s show and instead of moving on, similar to how she treats Dana Terrace (creator of The Owl House), Lily still drags Rebecca whenever she can, including insulting Rebecca’s talents in music and writing and art and it’s at that point that you start to wonder if its less ‘Rebecca made a show Lily didn’t like’ and more ‘does Lily just have a obsessive hatred for Rebecca?’

And the thing with Big Bang Theory and Harley Quinn was literally people seeing how convenient Lily will call out stuff in Steven Universe but if its shows Lily happens to like? Oh look at that, suddenly its being ignored, as Lily won’t ever dare call out stuff she likes.

And Lily acting like she has to talk about anime is just...no one’s making her. She’s choosing to talk about it. To the point of starting a whole dubs vs subs discourse where its clear Lily prefers dubs and thinks its okay to censor Japanese culture and even acted like there wasn’t much difference between Japan and America, even implying in her version of history that Japan got destroyed by America and basically colonized their culture and from how Lily spoke, she seemed happy about that idea and seemed to imply you can easily replace Japanese with English and....oh, would you look at that- suddenly it becomes less about ‘oh you just hate I said your favorite anime is bad’ and more people literally have found her being racist towards Japanese people and she wants to try and make it about anime.

Something that adds to her racism when she can only ever discuss Anime when it comes to Japan and yet, thinks its more popular in America then its own home country.

And oh god, the racism against black people accusations is far more then what Lily’s trying to paint them as:

*She only ever writes black women ocs as nothing but violent and easy to anger, including Aliana whose easy to get pissed and will murder on a whim and throw someone across a room and also proceed to colonize planets and force them to follow Sith culture, while her Harry Potter OC basically used a torture spell on Vernon and it was made to seem cool when anyone whose read Harry Potter, knows who are shown using those spells in the books (hint: not the good guys).

*She also wrote Aliana’s mom as being a slave trafficker and Aliana as a result, being fine with that and even getting mad if someone insults her mom for that.

*When it comes to The Owl House, she has basically fetished the idea of Hunter being black (saying it’d make him interesting) and for some reason, wanted the backgrounder character, Skara, to be more focused on instead of characters like Hunter and Amity, and there’s also how she treats Luz as soon as Luz stopped being the character Lily expected her to be.

And there is likely stuff I’m missing from this, but its less ‘oh i mixed words up’ and actually just again, Lily burying stuff.

And there’s a-lot of shit to unpack with her clearly proceed to slander someone throughout the rest of the post to try and make them the villain of her narrative, but the whole ‘Lily sends herself asks’ and ‘Lily lied about having cancer’ is literally because:

*When one of the NSFW Art website accounts was exposed to be Lily’s, Lily suddenly and conveniently got an ask warning her that ‘someone is pretending to be her on the website’...when not much on that situation had even come out at the time, so basically Lily played herself there, and then there’s asks that Lily gets that basically looks to be Lily’s writing style that also allows Lily to rant or slander or deny anything/anyone she wants to at the time.

*The cancer thing is still on-going but Lily has slipped up constantly in her cancer lying and keeps adding to the lying, all because now her sister has called her (and the twos brother) out for pretty serious allegations including molestation.

*And it should be noted that Lily also proceeded to slander her sister in response, trying to paint her sister as this mastermind villain.

And her calling someone terfy is also ironic, given Lily has gotten into hot water for lore in her Star Wars OC fic where...her OC basically said that only women can become siths, and if they happen to come out as trans male or non-binary while a sith, its okay because...they still considered sith women to their fellow sith.

Yeah uh, suddenly not so much of a hate wagon/wanting to tear Lily down as Lily claims it is, huh?

#lily orchard#i dont think i have everything here and i could be wrong in areas#so i am welcome to being corrected and such#but this whole post is just....#lily still trying to paint a narrative that doesnt exist#though her dedicated fans will buy it so

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Frozen 2: Dangerous Secrets Review Essay

Why Sensitivity Readers Are Always Necessary

Before I start, I would like to make it very clear that this review only critiques the aspects of colonialism and representation in Frozen 2: Dangerous Secrets. I will not be discussing the romance, side characters or anything else like that. Also, I would like to make it very clear that none of this review is meant to personally attack or berate the author @marimancusi . I firmly believe that none of the cultural insensitivities in her book were intentional, but were simply the result of a non-indigenous, white author writing about experiences she could not personally relate to. My only goals for writing this review is to show the author how her book unintentionally perpetuated many harmful and outdated ideas about racism and colonialism, and to convince her and Disney to contact and hire sensitivity readers before they create content about vulnerable racial/ethnic groups.

I would also like to state that I am an African American woman and not indigienous, so I have personal experiences with racism and colonialism towards black people, but not towards indigenous communities. So if any indigenous people see problems or inaccuracies with my review, I would be happy to listen and put your voice first.

- - -

To summarize quickly (with full context), Frozen 2: Dangerous Secrets is about Iduna, a young indigenous Northuldra girl (oppressed racial/ethnic minority) who was suddenly and violently separated from her home and family when her people were betrayed and attacked by the Arendellians (colonizing class). As a result of the massacre battle between the two groups, Iduna is permanently separated from her home (caused by a magical and impenetrable mist) and forced to spend the rest of her days in the kingdom of Arendelle, where she lives in almost constant fear of being exposed as a Northuldran (for the townsfolk are violently bigoted against them). Naturally, this book contains many many depictions of racial hatred and bigotry along with exploring the mindset and fears of a young girl dealing with the brunt of colonialism. Unfortunately, it tends to fumble the seriousness of these situations (out of ignorance or out of a desire to keep the book lighthearted/to center the romance plotline), which results in an overall detrimental message to the audience. The missteps I specifically want to unpack are as follows.

- (1/5) Severs Iduna’s connection to her culture before the story even begins (making us feel less empathetic for the Northuldra’s plight)

I’m not 100% certain, but my understanding is that the purpose of making Iduna a double orphan was to make her more sympathetic and to give her a reason to save Agnarr’s life (to have compassion for a stranger, the same way her adoptive family did for her). In theory this is perfectly fine, quickly establishing that the audience should like Iduna is smart and so is rationalizing her most important, life changing decision. But in practice this only functions to distance Iduna from her culture and family and make the reader care less about the Northuldra. This is because it takes away Iduna’s chance to have a strong, palpable relationship with a specific Northuldra character, which would humanize their entire group (even if only in memory). The only Northuldra characters that Iduna mentions more than once is her mother and Yelena. Both of these characters are mentioned rarely, neither have a close relationship with Iduna (her mother dying 7 years before the events of the story), nor do either of them have any specific personality traits or lines of dialogue (Yelena has exactly one line and it is about knitting). The goal of a story about a child unjustly stolen from her home should be to explore why those acts of violence were so horrific. The very first step of exploring that is to humanize the victims. After all, why would a reader care about the injustices done to a group of people who barely exist? How are we, the readers, supposed to feel bad for Iduna and mourn her family like she does, if we barely know them?

We needed more of Iduna’s memories. We needed to learn about her friends, her family, her mother and Yelena. What were they really like? How did they love Iduna? What were their last words to her before she never saw them again? Didn’t Iduna care for them? Did she worry about their well being and miss their comforts? We need to hear about how she bonded with them, how they made her feel, how they made her laugh or cry. How they taught her to hunt, forage, and knit so that when we hear how the Arendellians speak of them, with such ignorance and contempt, we are as truly disgusted and offended as we should be.

- (2/5) Equates Iduna and Agnarr’s suffering, aggressively downplaying the brutality of colonialism (even to the point of prioritizing Agnarr’s needs)

First things first, I understand that Dangerous Secrets is a modern day romance novel for older children/teens so an equal power balance between Agnarr and Iduna is preferred (which I agree with). But, this balance extends past the romance and personalities and into attempting to portray Agnarr and Iduna’s suffering as equal. This is best exemplified in these lines of internal dialogue by Iduna:

I did not deserve to be locked away from everyone I loved. But Agnarr did not deserve to die alone on the forest floor because he’d had a fight with his father. Whatever happened that day to anger the spirits and cause all of this, it was not his fault. Nor was it mine. And while we might be on different sides of this fight, we had both lost so much. Our friends. Our family. Our place in the world. In an odd way we were more alike than different. (Page 67)

All of this is technically true, up until the very last line about them being “more alike than different”. Agnarr and Iduna’s lives are nothing alike. Iduna is a poor, indigenous girl who had everyone she ever knew or loved either killed or permanently taken away from her, stolen from her home and forced to spend the rest of her life living in a foreign kingdom rife with people who actively, consistently threaten her safety. While Agnarr, on the other hand, is a white male member of the royal family, heir to the throne, and extremely wealthy. The novel doesn’t shy away from this (at least on Agnarr’s part), and doesn’t hesitate to show us that Agnarr is royalty and will never experience what Iduna has to endure. But it behaves like Agnarr’s relatively petty, temporary, and incomparable ills are just as heartbreaking as Iduna’s and focuses significantly more time and energy building up empathy for him and his woes. This extends from small things like the book asserting that the few times Agnarr needed to stay in his castle, to avoid political assasination was comparable to Iduna’s family being trapped in the mist (against their will for 30+ years); to more concerning issues like claiming Agnarr’s separation from his parent’s is just as distressing as Iduna’s separation from her entire people. Now fleshing out Agnarr and his relation to parents is a good thing, since it can provide crucial character motivation and make him more of a well rounded character. But when Agnarr’s suffering is presented as more relevant and worthwhile discussing than Iduna’s it, by extension, implies that the frustrations of an affluent life and being separated from parents that did not value you in the first place (Runeard and Rita) is somehow more or just as pressing as facing the brunt of the most violent and terrifying forms of colonialism. Agnarr’s story may be tragic, but it is nowhere near as horrific as Iduna’s and the book should acknowledge and reflect that.

- (3/5) Has a rudimentary understanding of racism and how if affects the people who perpetuate it

Dangerous Secrets’ understanding of racism (and how to deal with it) is summed up very concisely in a conversation between Lord Peterssen and young Prince Agnarr. Agnarr asks his senior why the Arendellian towns people are so obsessed with blaming magic and the spirits (magic and spirits being an allegory for real world characteristics that are unique to one culture or people) for all their problems, and the following exchange insues:

“People will always need something to blame for their troubles”, he explained. “And magical spirits are an easy target-since they can’t exactly defend themselves… “So what do we do?” I asked. “We can’t very well fight against an imaginary force!” “No. But we can make the people feel safe. That’s our primary job.” (Page 132-133)

Though Lord Peterssen is supposed to be a flawed character, who puts undue pressure onto Iduna and Agnarr to uphold the status quo of Arendelle, this line is (intentional or not) how the book actually views racism and how it expects the characters (and reader by extension) to deal with/understand it. Bigotry is portrayed as something that is inevitable and something that should not be quelled or disproven, but accommodated for. Agnarr, as king next in line, should not worry about ending the unjust hatred in his kingdom, or killing the root of the problem (the rumors). Instead he should tell his people their suspicions are correct, and put actual resources and time into abetting their dangerous beliefs. Even later on, at the very end of the novel, Agnarr treats the prolific bigotry and magic hatred of his people as an unfortunate circumstance he has found himself in, and not something that he, as king, has the power or civic responsibility to change.

This could have been an excellent line of flawed logic, representing how privileged people tend to avoid/project the blame of racism, and prioritize order and peace over justice. Which would work especially well for Peterssen and Agnarr since they are both high class nobles with the power to actually make a difference, instead choosing to foist responsibility onto Iduna (in the case of Peterssen) who was only a child, relatively impoverished, and the one with the most to lose if she spoke out. Or, in the case of Agnarr, they do disagree with the fear mongering, but only for personal reasons (Agnarr because his father used it as an excuse for his lies); refusing still to actually work to improve his society. But the key detail is that this needs to be portrayed as wrong, which this book fails to do. Agnarr nor Peterssen are ever expected to disprove the townsfolk’s bigotry in any meaningful, long lasting sense, Peterssen is never confronted seriously for his cowardice and victim blaming, and Agnarr is never criticized for his anti-bigotry being based entirely on his own personal parental issues and not in the fact that he knows with 100% certainty that the Northuldra are innocent.

This flawed understanding of bigotry also applies to how the book depicts the Arendellian townsfolk, who are awarded no accountability whatsoever for their actions. The townspeople spend the entire book threatening to kill any Northuldra they find and Peterssen, Agnarr, and Iduna are constantly afraid that they would immediately destabilize the government if they found out their king was close to one. But somehow this does not translate into any contempt or distrust in our protagonist or the reader. In this novel, we meet only four openly bigoted individuals: the two orphan children playing “kill the Northuldra”, the purple/pink sheep guy (Askel), and the allergy woman (Mrs. Olsen). The orphans are dismissed wholesale because they are literal children who also lost both of their parents in the battle of the dam (so they were killed by Northuldra; somewhat justifying their anger). And the other two townsfolk are joke characters, whose claims are so unbelievable that they aren’t supposed to be seen as a serious threat. Not only that but Askel is rewarded for his bigotry when Iduna offers he sell his pink sheep’ wool (which he thought was an attack from the Northuldra) as beautiful pink shawls. These are the only specific characters that show any type of active bigotry in the entire kingdom besides Runeard, whomst is dead. Every other character is either an innocent and friendly bystander (the woman at the chocolate shop, the new orphans Iduna buys cookies for, the farmers Iduna sells windmills too, the people at Agnarr and Iduna’s wedding), has no opinion at all (Greda, Kai, Johan), or is portrayed as someone who is just innocently scared and doesn’t know any better (the rest of the townsfolk, especially those who fear the Northuldra are the sun mask attackers). Even the King of Vassar, the most violent and dangerous living character of the story, doesn’t even hold any prejudice against the Northuldra, and simply uses their imagery to scare Arendelle into accepting his military rule.

So according to this book, bigotry and racism come not from the individual, but from society and the system you live in, but also not really because the people in charge of that system (Peterssen, Agnarr, and eventually Iduna) are also virtually guiltless. This, of course, is not true at all. Racism is a moral failing which exists on all levels of society, from individuals who chose to be bigoted, to others who tolerate bigotry as long as it doesn’t inconveniance them. It's not just an inevitable fear of what you don’t understand, but an insidious choice to be ignorant, fearful, and unjust to the most vulnerable members of society. It is malicious and irrational, and the more you tolerate it, the more dangerous it becomes.

- (4/5) Presents Iduna’s assimilation to the dominant culture as a positive

As the romance plotline of Dangerous Secrets really starts to get underway, Iduna’s life seems perfect. Her romance with Agnarr blossoms, she has her own business, and is becoming accustomed to her new surroundings (in order to make the coming drama more exciting). This is her internal dialogue as she returns to town one day:

I couldn't imagine, at the time, living in a place like this. But now it felt like home. It would never replace the forest I grew up in… But it had been so long now, that life had begun to feel almost like a dream. A beautiful dream of an enchanted forest… There was a time I truly believed I would die if I could never enter the forest again. If the mist was never to part. But that time, I realized, was long gone. And I had so much more to live for now… And my dreams were less about returning to the past and more about striking out into the future- (Page 128-129)

Again, I understand that the point of Iduna being content with her life like this is to be the “calm before the storm” of the romance arc, but the fact that Iduna is almost forgetting her old life, and that it is presented as a good thing, is extremely distressing. At only 12 years old Iduna lost everything she ever had besides the literal clothes on her back; she would never forget that. Not only that, but the real world implication that a minority should cope with their societal trauma by spending the rest of their life working for said society that unapologetically wants to kill them (and get a boyfriend) is horribly off putting. It strikes a nerve with many people of color and indigenous readers because telling minorities to “get a job” or “get a life” (especially when said jobs ignore/are separate from their own cultures) is commonly used by privileged folk to blame them for their own dissatisfaction/unhappiness with the society they live in. The idea is that minorities should continue to suffer, but busy themselves, so they stop criticizing dominant culture and defending/uplifting their own. This is part of cultural erasure, and the book plays into it, by commending Iduna for “having more to live for” than cherishing/wanting to return to her original home, for prioritizing Arendelle over herself, and for forgetting her heritage/playing it off as nothing but a dream. Devaluing indigenous culture like this, especially through an indigenous character, is extremely disrespectful.

Not only that, but it’s completely antithetical to Iduna’s character, since she claims to be proud and unashamed of who she is, but happily assists the townsfolk who hate her, and rarely mentions her heritage besides when she’s caught in a lie or actively being persecuted. This is another failing brought on by the lack of understanding of how racism affects its victims. Being a minority plays into all the decisions you make and all the interactions you have; it’s not something that you can just turn off unless directly provoked. Iduna’s would be constantly fretting about who she talks to, and who she is with because if she gets too close to the wrong person, she could have put herself in serious danger.

Nowhere is this lack of realism more obvious than the scene directly after Iduna rejects Johan’s proposal. Iduna spends a long time thinking about whether marrying Johan or Agnarr would be better for her, and not even once does being a Northuldra play into her decision making. This should’ve been front and center because your husband can be your strongest ally or your greatest enemy. If Iduna was outed, what could she do to defend herself against or alongside her partner? If she was ever going to consider marrying for anything other than true love, her chances of survival should have been her first priority.

What I’m not saying is that there needs to be a complete overhaul of Iduna’s personality, or that she needs to be frightened and suspicious at all times. Iduna can project strength and caution. She can be kind to the townspeople, but reserved in order to keep a safe distance. She should cling to the few pieces of her culture she has left, despite what society tells her to do. Or, on the exact opposite side of the coin, Iduna’s personality could be kept relatively the same, but the book needs to acknowledge that this is a terrible thing. Iduna is being assimilated against her will to a society that doesn’t value her and that is a tragedy. In a futile attempt at survival, Iduna buries her culture away and lives her life as a perfect, contributing, model Arendellian citizen, but they terrorize her regardless.

- (5/5) Negatively depicts the indigenous Northuldra as murderous invaders

In Chapter 34 of Dangerous Secrets it is revealed, during a flashback, that Iduna lost her parents and her entire family group in an attack by a separate group of Northuldra invaders. This scene is completely unacceptable regardless whatever narrative/story purpose it was supposed to achieve for several reasons. Firstly, because this book is about colonialism, which we as a society already know the consequences of and how colonizers, in an attempt to rid themselves of blame, react to it. One of the very first things a colonizer/privileged class will do to make themselves feel less guilty for the atrocities they perpetuate is bring up acts of violence/wrongdoing on behalf of the oppressed. The sole purpose of this is always to make the victims look less sympathetic and less deserving of justice, equality, or attention because “they’re not so innocent, they did wrong things too, so maybe we shouldn't feel that bad for them/maybe they got what they deserved”. And of course this mindset is absolutely horrific and unforgivable when you’re talking about a group of white colonizers actively trying to destroy and indiscriminately slaughter a large group of indigenous people, including their children.

The second reason is because the author is a non-indigenous white person, and therefore benefits directly from the downplaying of indiginous pain. I’m sure this wasn’t intentionally malicious on her part, but that’s what she wrote; these are the consequences.

((Also the fact that one of the Northuldra groups are murderous invaders means that Iduna was actively lying the entire book about the Northuldra being peaceful.))

- - -

In conclusion, any book that incorporates the culture and experiences of a group the author is not a part of, should absolutely hire a sensitivity reader to ensure accuracy and respect. As a Frozen superfan myself, I actually enjoyed this book a lot and I was delighted to see the lore, worldbuilding and romance. I loved Agnarr, Lord Peterssen, and Princess Runa and certain pieces of dialogue and imagery were beautiful. This novel just desperately needed someone to check it. All this book needed was a bit more of a critical gaze on some of the character decisions and motivations (I truly believe Agnarr and Peterssen would have been even more intriguing and likeable characters if they were actually called out, and given time to reflect on their hypocrisies) and it would’ve been much stronger and more palatable to diverse audiences. Some elements did need to be cut out completely, but a sensitivity reader would’ve easily been able to point this out and offer alternatives that preserved the spirit of the novel, without including any offensive and distasteful implications.

#dangerous secrets#Frozen 2: Dangerous secrets#agduna#iduna frozen#agnarr frozen#iduna#agnarr#frozen#frozen 2#dangerous secrets review#frozen reviews#frozen review#frozen analysis#frozen 2 analysis#Frozen 2: Dangerous Secrets Review

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

Excellent expose on racism and how to challenge white supremcy and our ideas about racism. It's well worth the time. He is brilliant!!!

Historian Ibram X. Kendi has daring, novel ideas about the nature of racism — and how to fight it

By David Montgomery | Published

October 14, 2019 1:17 PM ET | Washington Post | Posted October 20, 2019 |

Ibram H. Rogers, 17, hadn’t even told his parents that he was entering a Martin Luther King Jr. Day oratorical contest. They found out after he won one of the early rounds and they got a videotape of his performance. “We’ll never forget that Saturday morning we put the tape in and watched him,” Larry Rogers, Ibram’s father, told me recently. “We were really surprised.” Ibram was a bright but underachieving senior at his Northern Virginia high school. His GPA was below 3.0; his SAT scores were just above 1000. He thought he wasn’t smart enough for college, even though he had been admitted to historically black Florida A&M University.

The Prince William County Alumnae Chapter of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, sponsor of the competition, saw to it that the finale, in January 2000, was filled with pride. The MLK Community Choir serenaded the mostly African American audience of 3,000 that filled a local chapel. “It was a very proud moment,” recalls Carol Rogers, Ibram’s mother. “An awesome event.” Six students out of more than 100 contestants made it to the final round to deliver 10-minute speeches on “Dr. King’s Message for the Millennium.”

The contestants dressed like young business people — except Ibram, who wore a loud golden-brown blazer, black shirt, bright tie and baggy pants. (The fact that the public school he represented, Stonewall Jackson High School, was named for a Confederate general was one of those ironies that, in the moment, was too deep to dwell on.) For his speech, Ibram adopted the persona of an angry King come back to life to scold black youth for thinking “that the cultural revolution that began on the day of my dream’s birth is over. ... How can it be over when kids know more about Puff Daddy than they know about me? ... How can it be over when many times we are unsuccessful because we lack intestinal fortitude?” The speech swelled into a jeremiad of disappointment. Ibram paced around the pulpit as he reeled off more supposed failings of young black people: “They think it’s okay to be those who are most feared in our society! ... They think it’s okay not to think! ... They think it’s okay to confine their dreams to sports and music!”

The audience loved the message, reacting with “whoops of agreement,” according to a Washington Post account at the time. Ibram didn’t win the top prize, but, two days after the big night, a picture of him speaking was spread over three columns in The Post, with the headline: “Students Give New Voice to King’s Dream.”

Ibram H. Rogers has grown up to be Ibram X. Kendi, 37, a leading voice among a new generation of American scholars who are reinvestigating — and redefining — racism. In 2016, at 34, he became one of the youngest authors to win the National Book Award for nonfiction, for “Stamped From the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America” — which, gushed the award judges, “turns our ideas of the term ‘racism’ upside-down.” The following year, American University recruited him from the University of Florida to join the faculty and create the Antiracist Research & Policy Center. (The very evening in September 2017 when Kendi introduced the center at a gathering of students, faculty and administrators, someone stuck cotton balls to fliers depicting Confederate flags and posted them around campus.) More recently, the crowds turning out to hear Kendi discuss his new bestseller, “How to Be an Antiracist,” have been so large that bookstores have resorted to holding readings in churches, synagogues and school auditoriums.

Kendi’s ideas — that few, if any, are free of racism; that we should confess to our own racism as a first step toward becoming anti-racist; that racism begins not with the prejudice of individuals but with the policies of political and economic power — are bracing and challenging. They also constitute a very different take on race from the speech he gave at 17. For years afterward, he had vague memories of his MLK oration, and they were troubling. The competition, he told me, had been “a pivotal moment in my life” — one that gave him the confidence to believe that he was college material after all and that his future would involve communicating ideas to a larger public. Yet he also recalled how, a couple of years ago, when he took the time to watch his performance on a DVD that his father had made, “I cringed and was completely ashamed.”

The speech, he saw, had been a litany of blame, implying that there was something wrong with young African Americans as a group and that they could conquer white racism by behaving differently. How did these perspectives get lodged in the young orator’s brain? Why did the African American crowd respond with such enthusiasm? To his chagrin, Kendi realized his own experience was a prime example of how racist ideas quietly worm their way through the culture. It also showed all too clearly how one can be anti-racist in some contexts yet sick with racism in others.

Reflecting on the shame he felt at his words, he realized that the best way to communicate his newest message would be to hold out his journey as an example. Whereas his previous book, “Stamped From the Beginning,” had been built around five historical characters — Cotton Mather, Thomas Jefferson, William Lloyd Garrison, W.E.B. Du Bois and Angela Davis — he reluctantly concluded that his next book, “How to Be an Antiracist,” must be based on the errors and evolution of Ibram X. Kendi.

I think even the book got better after his diagnosis,” says Kendi’s wife, Sadiqa. “I think he was writing for his life.

“Initially, I was like, that central character will not be me,” he told me. “I’m too private. I don’t want to show all of my bones and all of my baggage and all those shameful moments that I’m still ashamed of. I don’t know — I don’t want to do that. But the more I thought about it, the more I realized: How can I ask other people to share those shameful moments, to free themselves of their baggage, to confess the most racist moments of their lives, if I’m not willing to do that, too?”

And so his work and his life have built to this moment of invitation to his readers, his audiences, America. After a precocious scholarly career spent demonstrating the depressing pervasiveness of racism, he stands uncommonly hopeful, inviting us onto a path forward. “We know how to be racist,” he writes. “We know how to pretend to be not racist. Now let’s know how to be antiracist.”

Recently, Kendi’s life and work have fused in another way, too — this one potentially tragic. In January 2018, after having drafted about five chapters of “How to Be an Antiracist,” he received a diagnosis of Stage 4 colon cancer. About 88 percent of people in that condition die within five years, he was told.

Kendi was devastated but still detached enough to fold his illness into his work. He began to make sense of racism through cancer, and to make sense of cancer through racism — essentially seeing both as diseases that can be systematically fought. He wrote through months of chemotherapy and recovery from surgery, taking naps when he was too weak to remain at his keyboard, then awakening to write some more. “I was like, you know what, I want to finish this book before I die,” he told me. Sadiqa Kendi, his wife, a pediatric emergency medicine doctor at Children’s National Hospital in Washington, kept watch to see that at least he didn’t work himself to death. “I think even the book got better after his diagnosis,” she says. “I think he was writing for his life.”

Have you noticed that almost everyone self-identifies as “not racist”? Consider: In June, responding to backlash over his fond recollections of working with segregationists in the Senate in the 1970s, Joe Biden insisted, “There’s not a racist bone in my body.” The following month, in response to backlash over his attacks on four women of color in Congress, President Trump tweeted, “I don’t have a Racist bone in my body!”

Kendi has little use for such protestations, for two reasons. First, he thinks “racist” should be treated as a plain, descriptive term for policies and ideas that create or justify racial inequities, not a personal attack. Someone is being racist when he or she endorses a racist idea or policy. Second, he doesn’t acknowledge “not racist” as a category. At all times, people are being either racist or anti-racist; in Kendi’s view, “there is no in-between safe space of ‘not racist.’ ” Through his scholarship, Kendi has traced nearly six centuries of racist and anti-racist ideas. He could not do the same for “not racist.” It’s an identity without content.

All policies, even the most trivial, are either racist or anti-racist, he argues — they support equity or they don’t. A do-nothing approach to climate change is racist because climate change overwhelmingly affects people of color on the planet. Forgiving student debt and offering universal health care would be anti-racist policies because people of color are more likely to have student debt or lack health care, so those policies would lessen if not erase those inequities.

In Kendi’s analysis, everyone, every day, through action or inaction, speech or silence, is choosing in the moment to be racist or anti-racist. It follows, then, that those identities are fluid, and racism is not a fixed character flaw. “What we say about race, what we do about race, in each moment, determines what — not who — we are,” he writes. In studying the history of racist ideas, Kendi has found the same person saying racist and anti-racist things in the same speech. “We change, and we’re deeply complex, and our definitions of ‘racist’ and ‘anti-racist’ must reflect that,” he told me. Those who aspire to anti-racism will, when accused of racism, seriously consider the charge and take corrective action. They will not claim to lack any racist bones. “The heartbeat of racism is denial,” he writes in his new book. “The heartbeat of antiracism is confession. ... Only racists shy away from the R-word.”

As for where racism comes from: A popular explanation for the genesis of racism assumes that people’s ignorance and hatred harden into racist ideas, which lead to racist policies. “But that gets the chain of events exactly wrong,” Kendi writes. From slavery to Jim Crow, from redlining to mass incarceration to the unequal distribution of government largesse, power has been the first link in the chain. Power, he argues, devises racist policies for economic self-interest and then justifies the racist policies with racist ideas of hierarchy, inferiority, necessity, greater good and otherness. These racist ideas are consumed and reproduced at large, giving rise to ignorance and hate. Stop focusing on people, Kendi advises: The smart anti-racist identifies racist policy and attacks the racist ideas justifying it.

Contemporary thinkers on race say Kendi’s approach represents a bold extension of previous work on the subject. Molefi Kete Asante, who in 1988 created the nation’s first PhD program in African American studies at Temple University (where Kendi got his doctorate in 2010), told me he recalls when Kendi returned to campus in February and presented his idea that racism begins with policies. “I remember how shocked we were when we first heard him lecture on that, and people, you know, had to go back and reread [his argument] to figure out how he does this work,” Asante says. “I think it’s a wonderful innovation. ... There were questions, and he defended himself quite well.” Kendi, he adds, “is really the ascendant African American intellectual of his time. ... He has attempted something that is in the Afrocentric tradition ... and that is: Let’s redo almost everything. Let’s look at everything and ask ourselves the question, What if we turned it upside down?”

Kendi’s contention that racist policies spur the creation of racist ideas, not the other way around, is not fully embraced by all scholars, including his doctoral adviser at Temple, Ama Mazama, professor of Africology. “I don’t think that the power of ideas can necessarily be minimized,” she says. “It would be great, like he suggests, if we want to do away with racism, we could have anti-racist policies. ... I’m not sure if it would work. ... Maybe too much damage has already been done, too much ignorance that would be very difficult to eradicate through anti-racist policies.” Still, she is proud of her “brilliant” former student: “His work is important. ... He’s also looking for solutions. It’s not just an intellectual exercise, it’s something much more than that.”

Members of Kendi’s own generation of scholars praise his ability to break through to a wider audience. It certainly helps that his writing is lyrically accessible. (Two years ago, Kendi contributed a short piece to a special issue of The Washington Post Magazine, in which he proposed an anti-bigotry constitutional amendment.) “I think it’s just astonishing that someone is able to have an intellectual history like ‘Stamped From the Beginning’ influence so many people’s thinking about understanding the undercurrents of white supremacy in the United States and its durability over such a long period of time, and then pivot to actually spending time with people to rethink the strategies of their own choices in their own life,” says Marcia Chatelain, associate professor of history and African American studies at Georgetown University, who, after the 2014 police shooting and subsequent protests in Ferguson, Mo., organized scholars to develop the Ferguson Syllabus, a curriculum aimed at digging into the marginalization of black and brown communities. “Ibram represents a generation that I see myself as part of where we take our ideas in a number of places and we take the feedback from a number of audiences, and we really struggle and grapple with how our work isn’t just confined by the traditions of academia, but is really defined by its ability to resonate in people’s lives and help them to move closer to the types of worlds that people have long imagined but never realized.”

One of Kendi’s early racial memories is from when he was 7 and his parents brought him to check out a private school on Long Island where he might attend third grade. The family, including Kendi’s older brother, Akil, lived in Queens at the time, but Carol and Larry Rogers were looking to send their children to a school outside the neighborhood. It was after school hours and the third-grade teacher, an African American woman, met them at the door. Are you the only black teacher? Ibram asked with uncomfortable directness. She was. Why are you the only black teacher?

“The beauty about being 7 years old is that chances are we’re not hypocritical, chances are we’re not filled with contradictions, and chances are we see the world for what is in the world,” Kendi told me, recalling the moment, which he also describes in “How to Be an Antiracist.” He credits his parents with anchoring him at an early age with enough pride in being black to make such an observation. Both rose from poverty to the new black middle class and had been inspired by the Black Power movement of the 1960s. His mother became a business analyst for a health-care organization, and his father became a tax accountant and later a hospital chaplain. As committed Christians, they were steeped in black liberation theology. They gave Ibram piles of books from a junior series on black achievers, which he devoured.

Kendi’s mother tried to explain all this about her son to the taken-aback teacher at the school, but they ended up not sending him there anyway. Instead, Kendi went to another school, where his third-grade teacher was white, and he engaged in his first anti-racist protest: After the teacher ignored the raised hand of one of his black classmates, and called on a white student yet again, Ibram sat in the school’s chapel and refused to return to class. The principal was summoned, and his parents were called.

“We tried to raise both of our sons, Akil and Ibram, to think for themselves, and if they want to challenge authority, then they have to be willing to suffer the consequences,” Carol Rogers told me. (Akil is now an event specialist for Sam’s Club in Florida, where Carol and Larry Rogers are retired.) Such was the anti-racist path his parents set Ibram on from an early age, but it’s a deceptively hard one on which to keep your footing. “How to Be an Antiracist” takes the form of a memoir, with Kendi interspersing his experiences with analyses of types of racism that he has found in himself: ethnic racism, bodily racism, behavioral racism, cultural racism, color racism, class racism, gender racism and queer racism. It’s hard to believe one person — let alone a scholar of racism — could have encompassed so much bigotry, but that’s Kendi’s point: Anyone can.

In college at Florida A&M, he wore honey-colored contact lenses for a time, until he realized this was a form of racism, privileging a look associated with another race. He dated a light-skinned woman, until he realized what a warped sensation this was causing among some of his friends, who wished they were dating light-skinned women, too. He dropped her and vowed to date only dark-skinned women — until he realized this was an equally twisted obsession, driven by racist colorism. During another phase in college, he determined that the problem with white people was that if they were not devils, maybe they were just plain destructive by nature — until he realized judging white people as a group is as racist as judging black people as a group.

He came to see in retrospect that even his parents had sometimes strayed from the anti-racist path. Like others in the black middle class, he writes, “My parents — even from within their racial consciousness — were susceptible to the racist idea that it was laziness that kept Black people down, so they paid more attention to Black people than to [President] Reagan’s policies, which were chopping the ladder they climbed up and then punishing people for falling. ... Americans have long been trained to see the deficiencies of people rather than policy.”

Kendi is harder on no one than himself. “I arrived at Temple as a racist, sexist homophobe,” he writes of the dawn of his graduate school career. His most important mentors in shedding those views — in learning how racism, sexism and homophobia intersect — were fellow graduate students Yaba Blay and Kaila Adia Story. “I learned from them that I am not a defender of Black people if I am not sharply defending Black women, if I am not sharply defending queer Blacks,” he writes. They held court in one of the common areas during study breaks and sent him scurrying to bookshelves for works by Audre Lorde, Bell Hooks and Kimberlé Crenshaw.

“What’s so wonderful about Ibram is that even though he talks about his journey, and here he is meeting me and Yaba and he’s some kind of black male patriarch homophobe, he never gave us that reception,” says Story, an associate professor of women’s, gender and sexuality studies at the University of Louisville. “He said, ‘Okay, these women, if I say how I’m feeling or how I’m thinking about freedom, they’re going to challenge me. ... So let me be open enough to actually listen to what they’re saying.’ And I’m grateful for that. ... Ideological vulnerability is so important when it comes to dealing with ideas of anti-racism and intersectionality.”

In 2011, Kendi was doing postdoctoral work at Rutgers University — turning his dissertation into his first book, “The Black Campus Movement” — when he met Sadiqa, who was doing a fellowship in pediatric emergency medicine in Philadelphia. He had reached out to her on Match.com. “We both kind of ended up in online dating in the same way,” she recalls. “We just didn’t have time but still wanted to pursue meeting people. ... I saw he was younger than me and said, ‘Well, there’s no way I’m going to date this dude. But I’m a nice person, so I’ll respond at least.’ So I responded and we ended up going back and forth on Match and communicating there for a little while. After a few back-and-forth messages on Match, I thought, ‘Well, gosh, this guy actually seems really cool, pretty mature.’ So I gave him a chance.”

After they had been dating for a few months, Sadiqa and Ibram had dinner at an Asian fusion restaurant in Philadelphia. There was a big statue of the Buddha against a wall, and a drunk white man climbed up and began fondling the statue, to the amusement of his friends. At least he’s not black, Sadiqa recalls saying of the white man. Why? Ibram asked. We don’t need anyone making us look bad, Sadiqa replied.

So began an extended conversation about “uplift suasion,” another racist concept Kendi realized he needed to shed — the assumption that black conduct is to blame for white racist ideas, thus legitimizing white racist ideas about black conduct. “I realized early on that if I’m going to be with Ibram, we’re going to have some discussions on some stuff that is deep,” Sadiqa told me.

By 2013, they were ready to make plans for a spring wedding on a beach in Jamaica, which Essence would photograph for a “Bridal Bliss” feature. There was one more detail to take care of, another case of life and work merging: During his painstaking hunt for the origin and effect of every racist idea he could find, Kendi had discovered that perhaps the first racist idea — grouping all Africans as a single, inferior people — is contained in the 1453 biography of arguably the first racist, Prince Henry the Navigator of Portugal, who was the first European to orchestrate a slave-trade that exclusively targeted Africans. The moment is also significant because, Kendi would argue later, it marked the original case of a racist policy, created out of economic self-interest, being justified by a racist idea: that captive Africans were being civilized and saved by slavery.

The budding historian and evolving anti-racist — still known then as Ibram H. Rogers — became uncomfortable with his middle name: Henry, after his enslaved great-great-great-grandfather. He reasoned that the fate of his ancestor Henry had been set in motion by the original racist, Prince Henry. So as part of the wedding ceremony, with Carol and Larry Rogers officiating, Ibram adopted the middle name Xolani, meaning “peace” in Zulu. At the same time, he and Sadiqa took the last name Kendi, which means “loved one” in the Meru language of eastern Africa.

On a Tuesday evening in mid-August, Kendi brought his ideas to a packed crowd of 575 people invited by a local bookstore to Congregation Beth Elohim in Brooklyn. It was the first stop on his marathon tour for “How to Be an Antiracist,” with dates scheduled through March. It also happened to be his 37th birthday, and his parents, wife and 3-year-old daughter, Imani, were in the audience. Activist and writer Shaun King was seated beside Kendi at the front of the sanctuary to lead the conversation. “Who needs this book?” King began. “Who is this book for?”

Anti-racism, Kendi said, “is recognizing how we’ve been trained, nurtured and educated in ways to be racists. How hard it is to grow up in a racist society, where racist ideas are constantly being rained on your head, and never get wet.” That’s why, he concluded, the book is “for people who think somebody else could use it instead of them. Because I know I needed this book when I was 30, when I was 25 ... and I could even still use this book today.”

He started his answers to King’s questions low and slow. As he got swept up in his argument, his voice picked up speed and gained about an octave in outrage. At one point, Imani emerged from the audience and climbed into his lap. She listened quietly until Kendi wheeled into a riff about how there are only two explanations for a racial inequity such as black unemployment being significantly higher than white unemployment: “Either there’s something wrong with black workers — [which is a] racist idea — or there’s something happening to black workers as they move into the job market” — i.e., racist policies. “Relax, Daddy!” Imani said.

The audience on this night was predominantly white, as it was on the other two occasions I watched Kendi discuss his work and sign hundreds of books: at a church in Lower Manhattan and at Sidwell Friends School in Washington. Kendi has a lot to say to the types of white people who flock to book events about racism. “I can talk all day about how endemic racism is within American conservatism,” he said in Brooklyn. “But when you look at radical thought, when you look at progressive thought, when you look at liberal thought, there are prevailing racist ideas that people are not confronting. Liberals have long made the case there’s something behaviorally or culturally wrong with black people — progressives and radicals have long made the case there’s something behaviorally wrong with black people — but that those inferior behaviors come about as a result of their oppression, their poverty, slavery. ‘Yes, they are inferior, but [it’s] because of what they’re experiencing, the racism they’re experiencing, so that’s why you need to fight racism!’ ”

Kendi calls this the “oppression-inferiority thesis” — the often well-meaning but always destructive idea that mass oppression must manifest itself somehow in defective group behavior, hence the pitiable group must be championed. In “Antiracist,” Kendi quotes abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison’s preface to Frederick Douglass’s slave narrative of 1845: Slavery degraded black people “in the scale of humanity. ... Nothing has been left undone to cripple their intellects, darken their minds, debase their moral nature, obliterate all traces of their relationship to mankind.” Then there is Barack Obama’s campaign speech on race in 2008: “For all those who scratched and clawed their way to get a piece of the American Dream, there were many who didn’t make it — those who were ultimately defeated, in one way or another, by discrimination. That legacy of defeat was passed on to future generations — those young men and increasingly young women who we see standing on street corners or languishing in our prisons, without hope or prospects for the future.”

I think a lot of times we think about this as the work for other people, specifically white people,” says high school teacher Tamika Golden, “and I recognize that this work is for all people.

On the contrary, Kendi told any progressives in Brooklyn who might think that way, “you assume that since the system is dehumanizing, that it is literally making the people subhuman. No. The beauty of humanity is we have the capacity and the ability to strive and thrive in the most horrible, oppressive and dehumanizing conditions. And certainly black people did that during slavery, and they’ve been doing that ever since.”

The white audience members I spoke with after the events were looking for a way to describe what they were seeing in the America of 2019. “There’s a lot of categories of awfulness going on,” said Miles Seligman, a medical coder in Brooklyn. “There’s nothing — from the message and the language and the vocabulary of this kind of book — that can’t help me understand that better.”

Moreover, the example of a black man going first in a prospective communal racial confessional — and this black man’s conception of racism as a curable condition rather than a damnation for all time — seemed to encourage white listeners to look inward. “Racism doesn’t necessarily make you a bad person,” said Jimmy Dabrowski, who took three trains from New Jersey to hear Kendi at the church in Lower Manhattan. “You have to be willing to accept it and then face the reality that anti-racism is the only way forward.” Dabrowski is a health and phys-ed teacher at an elementary school in Perth Amboy. “I’m not an activist,” he said, “but I would hope that maybe by initiating a policy change where we have anti-racism in schools — that’s the kind of activism in my field I want to push for.”

The black audience members I met were already familiar with Kendi’s work. They came clutching well-thumbed copies of “Stamped From the Beginning.” In other words, they did not need to be taught the language. Rather, they were here to heed Kendi’s call for everyone to aspire to more-perfect anti-racism.

“What led me to his work was the belief that what I offered to my students had to be more than what I was giving them now,” said Tamika Golden, a high school English teacher in Brooklyn who uses “Stamped From the Beginning” in her classes. “I needed to figure out what it meant for me to be an anti-racist and to truly work against the socialization and the feelings and thoughts I had about my own people as a group. ... I think a lot of times we think about this as the work for other people, specifically white people, and I recognize that this work is for all people.”

Anwar Abdul-Rahman, principal at a charter middle school in Brooklyn where the majority of students are black or Latino, told me Kendi’s work offered “a framework for looking at racist ideas in America. You have your segregationists, you have assimilationists, and then you have your racist ideas and then counteracting that with anti-racism and what does that look like — I thought that was just a real profound idea that even as a black man was something that I could use in my life.” He, too, finds ways to work Kendi into the curriculum.

To his publics of all races, Kendi offers the same redemptive promise. In Brooklyn, King had asked him to read a couple of pages aloud. Kendi’s voice, now sonorous and incantatory, transformed the passages into a prose poem, ending with this paragraph: “But there is a way to get free. To be antiracist is to emancipate oneself from the dueling consciousness. To be antiracist is to conquer the assimilationist consciousness and the segregationist consciousness. The White body no longer presents itself as the American body; the Black body no longer strives to be the American body, knowing there is no such thing as the American body, only American bodies, radicalized by power. "

Kendi received his cancer diagnosis just as he was focusing his writing on the role of denial in the persistence of racism — all those folks who say they are “not racist.” At the time, he was a seemingly healthy, relatively young man with no apparent risk factors. Denial was an option for him, too.

“If I would have denied that I had cancer, then the cancer would have just continued to spread and eventually would have killed me,” he told me. “I had also been thinking about, even before the diagnosis, about how important it is for Americans to stop denying the existence of racism itself. ... The fact that in order for America to survive racism, they had to stop denying racism. Then, in that moment — in that same week — I was diagnosed with metastatic cancer.”

When he felt better, he began to write new sentences — hopeful sentences — that found their way into the last chapter of the new book: “We can survive metastatic racism. Forgive me. I cannot separate the two, and no longer try. ... What if we treated racism in the way we treat cancer? ... Saturate the body politic with the chemotherapy or immunotherapy of antiracist policies that shrink the tumors of racial inequities, that kill undetectable cancer cells.”

Sadiqa told me she and Ibram had a deal during his treatment regimen. He could continue to write, lecture, run the Antiracist Center, as long as he would listen to her on the occasions she detected he was pushing himself too hard. “People heal differently, and for him, he needed to have some semblance of his life, of his work, in order to mentally have the fight that I knew he would need for healing,” she said. “Pushing and making that will-to-live larger than giving up and succumbing to something that, if you just look at the numbers, was likely to take his life.” At least once, when he had a bad fever during chemo, she ordered him to cancel a speaking trip. “He was upset, but he listened,” she said.

After six months of chemotherapy, at the end of summer 2018, surgeons removed tissue in which pathologists found no cancer cells. This past summer, his body was scanned and all looked clear. “I can’t necessarily call myself a survivor as much as I’m surviving it,” Kendi told me. “But I think I’m headed in a good direction.”

And the rest of us? What direction are we headed in? The popularity of his books and the size of his lecture crowds are signs that more and more people are willing to look inside themselves to consider their own racism. At the talk in Brooklyn, King asked Kendi where he finds hope. Kendi went through the history of anti-racist progress, then added, “In order to bring about change, you literally have to believe in the possibility of change” — just as you have to believe in the possibility of a cure. “Here I am,” he told the audience, “cancer-free.”

But for America, it’s touch and go. Racist ideas continue to kill — that’s no metaphor — as the El Paso shooter most recently demonstrated. At times, Kendi sounds like an oncologist who has seen the worst. “It’s the same case with racism,” he told me. “You have people who do not want to take America, or even themselves, through the pain of healing because they’re convinced that it’s not going to work. Which makes sense if they’re convinced it’s not going to work. But once we convince ourselves that America can never heal itself from racism, then racism will persist and, I suspect, eventually destroy this country.”

David Montgomery is a staff writer for the magazine.

#black lives matter#black and white#racism#white supermacists#u.s. news#u.s. politics#us politics#politics and government#politics#african american history#american history#history#equal rights#equality#all lives are equal#currently reading

0 notes

Text

My 15 favorite books

I made a Top 15 of my favorite books and explained why. They are listed as they came to my mind.

1. Dancing on our Turtle's Back (Leanne Simpson, 2011)

With this book, Leanne Simpson shows a path towards an Indigenous resurgence. She does it by exploring the philosophical thoughts and sociopolitical theories of her people, for instance, through the study of the etymology and epistemology behind words, intergenerational meanings associated with Creation stories and systems of governance such as breastfeeding as a treaty, that I quoted in my earlier post Allaiter, un acte de résurgence. This book got me into thinking about how can we (e.g. Les Québécois) resurge? How are we infected by colonialism? How do we clean ourselves from it? How do we update and live our ancestors’ ways of seeing and being in the world? This is the reason why I started to focus more on my positionality and on my own family story. It’s something I’ve been reflecting on after reading the impacting article Decolonization is not a metaphor and Vine Deloria Jr’s Custer Died for your Sins.

2. A People's History of the United States [Une Histoire Populaire des États-Unis] (Howard Zinn, 1980)

Take a look at this video, and you’ll get why it came right away. It’s inspiring as it exposes the development of settler colonialism and imperialism in the US.

youtube

I simultaneously read Zinn’s short autobiography You Can't Be Neutral on a Moving Train: A Personal History of Our Times. He is such an inspiration for me as a person, as an engaged researcher, an organic professor, and a militant.

3. Les Damnés de la Terre [The Wretched of the Earth, Los condenados de la tierra] (Frantz Fanon, 1961)

I highly recommend this book to activists and engaged researchers. He’s the heart of national liberation or decolonizing thinking. Frantz Fanon is a psychiatrist from Martinique who participated in the National Liberation Front of Algeria at the of the 1950′s. He died from Leukemia in 1961. He left a great legacy as an analyst of the pervasive grips of colonialism on our minds and of its traps as it intertwines with nationalism (fabricated by the national bourgeoisie). He also exposes results from his work with patients who’s colonial violence experiences are reflected in their tensed and muscular dreams. If there is something i always recall from that book, is that according to Fanon, you see people’s decolonization as they recreate themselves, through arts for instance. I see it as the beginning of the resurgence process. Like me, Fanon was very skeptical of the uses of history in national liberation processes.

4. Settler Sovereignty (Lisa Ford, 2010)

Comparing “settler colonialism” in Georgia and New South Wales, Lisa Ford reflects on how settlers (I would also say colonizers) consolidate their sovereignty on the Indigenous lands and peoples through state building. It’s close to what I have been researching in Uruguay by putting together colonialism, capitalism, and nationalism.

5. Red Skin, White Mask (Glenn Coulthard, 2014)

I have to say I was first attracted by the title but was rapidly aligned with Coulthard. In his work, he focuses on colonialism and capitalism as interdependent socioeconomic phenomenon. He also takes a look at the “Identity Politics” in Canada by exploring the relationships between his people, the Diné, and the government of Canada.

6. Peau noire, masque blanc [Black Skin White Masks, Piel negra, máscara blanca] (Frantz Fanon, 1952)

Here Fanon explores how colonial thought influences relationships, intimacy and interbreeding among people who’s gender and skin color vary. He takes his own experiences in Martinique as a sample, then in France as he was studying to become a psychiatrist. He suddenly realized how Black people were “surdéterminés de l’extérieur” (”overdetermination from the outside”).

7. The Autobiography of Malcolm X [L'autobiographie de Malcolm X] (1992)

Malcolm X or Malek El-Shabazz deeply impacted the Black Power Movement with its incisive critiques of US colonialism, racism, and imperialism. He made me conscious of the importance to be open-minded and humble so to change my perspectives and ways of being since it is necessary for becoming “righteous” or coherent with our vision of the world. I like X because he not only puts emphasis on decolonization as a public struggle but also as an inner collective and personal process.

8. Thérèse Raquin (Émile Zola, 1867)

It’s funny how we sometimes refuse to do something because we “have to”, no? We’ll I’m a bit like that. I had to read this book in College (Cégep) in a Literature class, but only read it completely years later. Zola impulses naturalism as a literary movement. He not only shows how the ambiance is or feels like but also how people’s mind is distorted and what they are willing to do for freedom and love. I can re-read this book on and on.

9. The Dispossessed [Les Dépossédés, Los desposeÃdos] (Ursula K. Le Guin, 1974)

I was introduced to Le Guin at the ls Librairie lâInsoumise, an anarchist bookstore on Saint-Laurent in Montréal. I was looking for a political science fiction book. In The Dispossessed, she shows us what an anarchist setting could look like and she sometimes highlights it through its interaction with a capitalist one. Sheâll make you dream and think of âdecolonial loveâ, relationships and knowledge. This is the kind of book that impacts your political walk of life, how you will, later on, deal with decision making and relationships.

10. The Caves of Steel [Les Cavernes d'acier, Las bóvedas de acero] (Isaac Asimov, 1954)

Asimov and his série Foundation is about human relationships with robots. The Caves of Steel is about the necessary filiation of a human from the earth and a robot detective to investigate the murder of a detective on a planet where professionals once got to migrate in order to save their lives. I like this book because he made me think of our relationships with technological developments and to go beyond appearance.

11. Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation (Silvia Federici, 2004)

I met Silvia Federici at the 2017 Anarchist Bookfair in Montréal. It was love at first sight. But I first got to know her through a Charrua friend who dug the relationships of Indigenous women and colonialism. Federici explores how capitalism separated men and women as a subaltern unit and dispossessed women from their political power in order to commodify land and work. To do this, she investigates witch hunting in Europe. It was quite relevant to me as most Charrua women I met during my fieldwork were descendants of midwives and healers... and I descend from voodoo and tarot practitioners. Her work associates well with the Indigenous feminism movement and its stance on colonial traditionalism.

youtube

12. Wasáse. Indigenous Pathways of Action and Freedom (Taiaiake Alfred, 2005)

Alfred introduced me with Peace, Power, and Righteousness to the Indigenous resurgence movement and how to contribute as an âorganic intellectualâ to remove consent to the system that oppresses us. I like Wasáse, the warriorâs dance because it offers us a path to a resurgence that works through cleaning our inner self, reconsolidating relationships within our collective and confronting oppressive external powers according to our own philosophical principles and as a political unity. Itâs quite similar to what Malcolm X was advocating for. Alfred does so by exploring individualsâ path to resurgence and the possibilities of being autonomous towards colonial powers.

13. Los dones étnicos de la Nación (Diego Escolar, 2007)

This one can to my mind because Escolar shows how settler colonialism and nationalism affect our settler and Indigenous minds in seeing and living an Indigenous present.Escolar does so by exposing Indigenous oral histories and settler colonial archives in the light of the return of supposed Indigenous extinct groups in Argentina.

14. Roots of Resistance. A history of Land Tenure in New Mexico (Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, 1980)

This is a brilliant book if you want to know the history of the south of the United States, you know where Trump is building his fence. Dunbar-Ortiz looks at an Indigenous territory that has been colonized by multiple interests and empires through time and how its Indigenous peoples were used to protect foreign sovereignties, but also how they resisted to colonialism.

15. Little Red Book, Petit livre rouge, Libro Rojo] (Mao Tsedong, 1964)

I think Mao ended up here because I had the Black Panthers Party in mind. Iâm not a Maoist, but I am curious. This book, along with The Wretched of the Earth, put up the table for national liberation movements in the 1960â²s by advocating for an armed and cultural revolution. The 1960â²s are the golden era of activism.

#settler colonialism#frantz fanon#malcolm x#settler#sovereignty#zinn#united states#history#land tenure#indigenous#resurgence#decolonizing#decolonization#colonialism#colonization#literature#national libertion#nationalism#bourgeoisie#books#top 15#science fiction#anthropology#classic literature#classics#mao#maoism#realism#naturalism#revolution

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

January is (finally) over! In this post, I’m going to wrap up what I read for the Own Voices Global Challenge for Indigenous America, share with you some cool playlists and accounts I love on Instagram, and we’re going to close up with a bit of info on some current topics in Indigenous America that you should be aware of. Let’s go!

What I Read

The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie

This book is a cornerstone of Native American young adult literature. Released in 2007, Alexie racked up a ton of awards and nominations for this book, including National Book Award for Young People and the American Indian Youth Literature Award for Best Young Adult Book, but it also was banned in some places for discussing sexuality (it’s about a high school boy, what do you expect?!). It follows the trials and tribulations of high-schooler Junior as he navigates his indigenous identity. Ultimately deciding to leave the reservation school for a better education at a white school, Junior deals with the fallout among his friends back home, deals with new bullies and casual racism at his new school, and finds his feet as a basketball star. Overall, I found the book real and charming in the ways that teen books can be. I’m not a huge contemporary YA reader, so the genre didn’t help the book in my opinion, but I did like the nuance of the Indian experience in this novel.

The Heartbeat of Wounded Knee: Native America from 1890 to the Present by David Treuer

Let me begin by saying I loved this book. I’ve gotten really into nonfiction lately, and when I heard about this book I had to get it. Shortly after, I made the global reading challenge so it worked perfectly! It’s a hefty book, filled with a lot of political discussion and history, so be prepared for that, but I think it’s an absolutely essential read for Americans. Treuer recounts Indigenous North American history from prehistory to the beginnings of colonization in the first part, so don’t let the title mislead you — it’s an absolutely comprehensive look at Native American history literally to the present day. It’s filled with stories, data, reflection, and conversation. I loved Treuer’s conversations with modern Indian people across the country, and I think the power of this book really lies in the honest and raw look at how the American government is corrupt, crooked, and ultimately deeply racist and biased. There is no making America great again, because Treuer points out that America was never great to begin with. However, this isn’t all doom and gloom and disaster. Treuer remains optimistic and hopeful, noting that while America may never have been great, we can make it great ourselves. The greatness of America isn’t in the past, but in the future that we can form and craft and shape to benefit everyone who lives here.

Heart Berries by Terese Marie Mailhot

This one was hugely recommended to me. It was a quick read, taking me perhaps only a couple of hours to read. This book was also outside of my genre comfort zone, as I don’t usually read memoirs (the occasional celebrity memoir but those are limited). It wasn’t my cup of tea, I think for the genre alone, but there were some aspects I really liked. I liked the look at the modern Indigenous American identity off the reservation in the modern world. I think a lot of popular Indigenous works are popular because they take place on the reservation which is really a way for white readers to gawk at the Otherness of Indigenous people. I also liked the frank discussion of mental health and the struggles that people who are neuro-divergent and/or traumatized face when they are dealing with people in their lives who don’t get what mental health can be like. I’ll be honest: I did not like Casey, and I was quite upset to hear that Mailhot had continued her relationship with him. Oh, well. To each her own!

P.S. I started Trail of Lightning by Rebecca Roanhorse (pictured above), but I just couldn’t get into the story. Edgy supernatural fiction isn’t really my speed!

Check This Out

I like to tune my playlists to what I’m reading. While I was reading Treuer’s book and Mailhot’s memoir, I wanted a playlist that helped me settle into the Indigenous American world and music is a huge way that I do that. I found a set of playlists on Spotify, and particularly enjoyed listening to a variety of genres and styles of music (search Native America on Spotify to find the genre!). Here’s what I most enjoyed:

This is Redbone – I’m obsessed with “Come and Get Your Love” and “The Witch Queen of New Orleans”.

Dreamcatcher – This was a great instrumental playlist, but it did make me kinda sleepy.

This is Mary Youngblood – A mix of singing and instrumentals, this playlist was really soothing and relaxing.

I follow some great instagram accounts for Indigenous people who share great resources, make amazing art, and are activists for the modern Indigenous American community. These are just a few of the ones I engage with, so make sure to follow links, explore their pages, and support them if you can! Share their work, find new voices, and listen to them. They’re amazing!

@maybell.eequay – Maybell is such a beautiful soul and makes such amazing traditional Indigenous art. Her bitten birchbark art is so insane and beautiful! She often sells her beadwork via her stories so keep your eyes peeled! She also shares a lot about her tribe’s native language which is really interesting and a huge issue in the Indigenous community as the languages struggle to survive.

@lamalayerbalove – Xochitlcoatl is an indigi-queer activist who shares inspiring and affirming messages on their page at the same time that they work to dismantle patriarchal, racist, and exclusive structures in the world. They are positive, affirming, and spiritual. Great resource to learn about the intersections of identity.

@the_sioux_chef – I learned about Sean Sherman from Treuer’s book and was so intrigued by his mission to make food with the indigenous ingredients that the Indigenous populations of the northern US would have used. His food is so beautiful and looks so yummy. He’s also an activist for Indigenous people and speaks often about Native American history being American history.

Finally, I want to close out with some links to info that you should know about.

Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women: According to the Coalition to Stop Violence Against Native Women, 4 out of 5 Indigenous women are affected by violence and they are 10 times more likely to be murdered. These are shocking and terrifying numbers. The MMIW movement is seeking to bring public awareness to this issue, help find missing girls and women, solve their murders, and change the patriarchal and sexists mindsets that allow this violence to continue unchecked. Check this site to find out more about this movement and how you can help those affected.

Racist Sports Mascots: This weekend is Super Bowl Weekend, and this year, the Kansas City Chiefs are playing on the biggest field in the world. The use of Native American imagery, tropes, and stereotypes in sports is not news, but for the first time in a while, this fight is being taken to the national stage with the Super Bowl. Here in Atlanta, we have our own history of negative stereotypes in sports, as for years the Braves national baseball team used a Native American mascot and still performs tomahawk cheers in the stands. Tara Houska took to the New York Times to share her grievances and griefs on this topic in a moving essay about the damage of this old-fashioned racism.