#lindisfarne

Text

Lindisfarne Castle

Some pics of a great wee trip to Lindisfarne Castle/Holy Island with my pal Laura Summers yesterday. Laura did her homework on this, first was the tides, it's a tidal island only accesableby a causeway, thursday was one of the days that the low tide would be at it's longest duration, secondly, aftera week ofof chanheable weather the forecast wasfor a sunny day, great work from her, the only thing was that half of Northumbria and beyond had alsodescended on Lindisfarne.

I've only addeda few pics of the castle, Ispent a wee bit editing themand erasing someofthe peoplethat got in the wayofphotoes, and a silly looking flag on topof thestronghold.

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

LINDISFARNE/MEDCAUT (HOLY ISLAND), MARCH 2024.

20 notes

·

View notes

Photo

lindisfarne priory, holy island, northumberland, england, july 28th, 2023

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

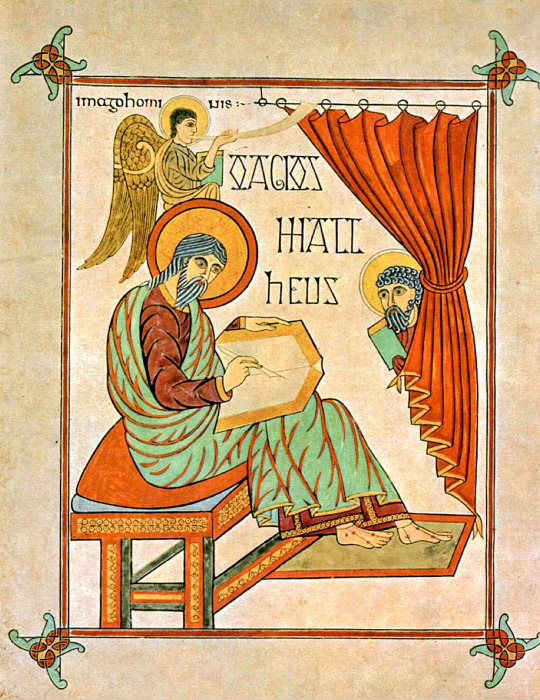

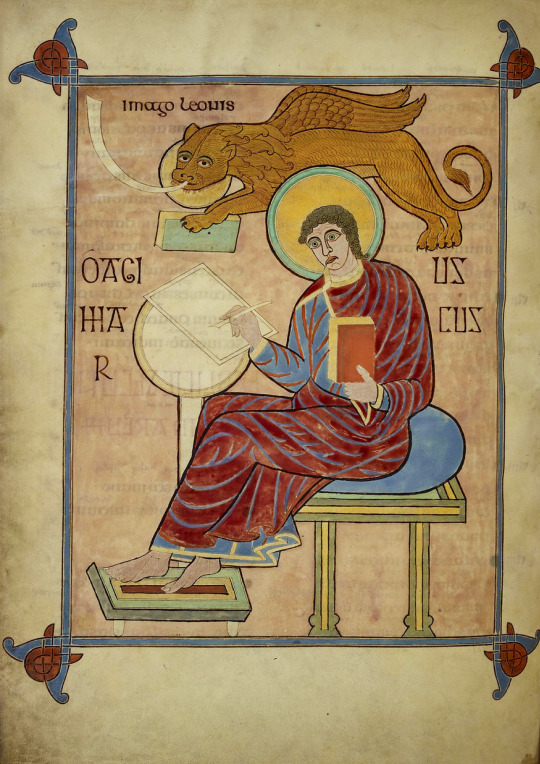

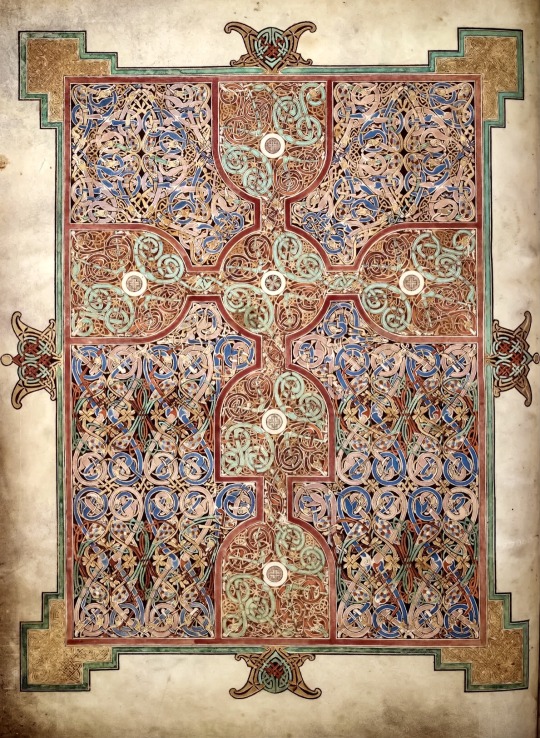

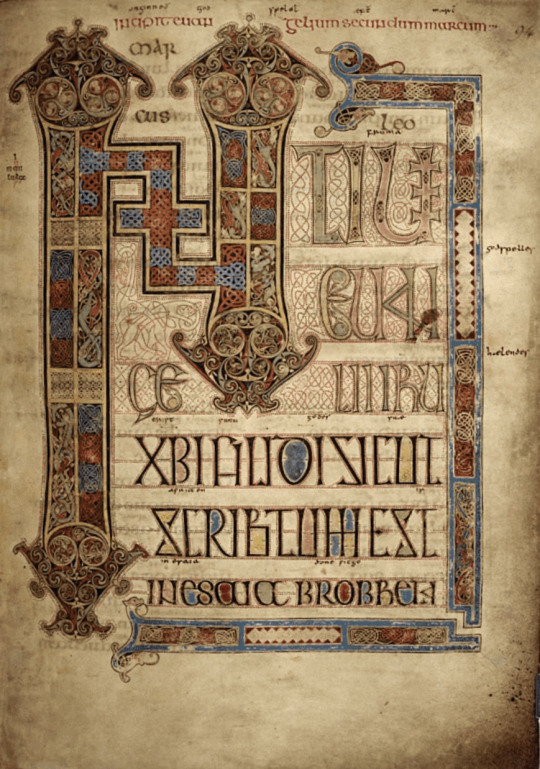

THE LINDISFARNE GOSPELS (c. 700) Modern binding, commissioned in 1852 by Edward Maltby, Bishop of Durham. It is one of the first and greatest masterpieces of medieval European book painting. The Lindisfarne Gospels is described as Insular or Hiberno-Saxon art, a general term for manuscripts produced in the British Isles between 500 and 900 AD.

The story of the Lindisfarne Gospels is intimately connected to life in the north east of England. It speaks to the migration of communities, the passing on of artistic traditions and the preservation of a communal history that resonates with modern-day concerns around identity and belonging.

One of the most characteristic styles in the manuscript is the zoomorphic style (adopted from Germanic art) and is revealed through the extensive use of interlaced animal and bird patterns throughout the book. The birds that appear in the manuscript may also have been from Eadfrith's own observations of wildlife in Lindisfarne. The geometric design motifs are also Germanic influence, and appear throughout the manuscript.

The carpet pages (pages of pure decoration) exemplify Eadfrith's use of geometrical ornamentation.

As a part of Anglo-Saxon art the manuscript reveals a love of riddles and surprise, shown through the pattern and interlace in the meticulously designed pages. Many of the patterns used for the Lindisfarne Gospels date back before the Christian period. There is a strong presence of Celtic, Germanic, and Irish art styles. The spiral style and "knot work" evident in the formation of the designed pages are influenced by Celtic art.

source

source2

#beautiful books#book blog#books books books#book cover#books#old books#incunabula#illuminated manuscript#book design#book binding#treasure binding#gospel#lindisfarne#carpet pages

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

A lot can be learned about the #Viking mindset by studying the Old #Norse sagas. A blend of vengeance, black humor and a belief in fate drove these fearsome warriors.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Getting back to Marmion! Some bits of context for the last few days’ posts.

A palmer was sort of a continual pilgrim, who spent a period of time travelling to holy sights and praying. The greatest holy sight of all was Jerusalem, where the palmer in the poem has in fact been, along with a huge list of other holy sights, from Mt. Ararat where Noah’s Arc reputedly came to rest after the Flood, to Mt. Sinai, to Santiago de Compostela in Spain, and in England Durham and Canterbury among others.

I think (I am not sure) palmer paid for their travels in part by donations from pious people, who might want the palmer to pray for them at some shrine. Marmion himself expresses a more lighthearted picture of palmers in general -

I love such holy ramblers; still

They know to charm a weary hill,

With song, romance, or lay:

Some jovial tale, or glee, or jest,

Some lying legend, at the least,

They bring to cheer the way.”

- and that may not be unrealistic for a category of people that could have included the medieval equivalent of a tourist with a GoFundMe. But this palmer is not of that kind - he’s haggard and gloomy, and kind of disturbing with his nighttime mutterings. But Marmion chooses to accept him as a guide all the same, and the next morning the whole group departs.

The first canto (The Castle) ended, we switch scenes and characters for the second (The Convent), to a boat travelling north, up the eastern coast of England, from Whitby to the island of Lindisfarne (also called St. Cuthbert’s Isle) with a group of nuns aboard. Now, where has Lindisfarne been mentioned in the previous canto? In the bit about Marmion’s former page:

That boy thou thought’st so goodly fair,

He might not brook the Northern air.

More of his fate if thou wouldst learn,

I left him sick in Lindisfarne:

The voyage is both a little scary and exciting for the nuns, who don’t get out much. Many of the castles the pass, like Warkworth and Dunstanburgh and Bamburgh, are ones you can still see on the Northumberland coast today.

But two of the group in particular are not having fun: the abbess (chief nun), who is not named, and the novice (i.e., has not yet taken vows and become a nun) Clare. Clare joined the convent recently after the loss of the man she loved, and in order to escape an unwelcome suitor who is trying to marry her in order to get at her property.

She was betrothed to one now dead,

Or worse, who had dishonoured fled.

Her kinsmen bade her give her hand

To one who loved her for her land;

Herself, almost heart-broken now,

Was bent to take the vestal vow,

And shroud, within Saint Hilda’s gloom,

Her blasted hopes and withered bloom.

On top of these griefs, there’s been an attempt to murder her, and the people who attempted it are now prisoners in Lindisfarne awaiting trial:

And jealousy, by dark intrigue,

With sordid avarice in league,

Had practised with their bowl and knife

Against the mourner’s harmless life.

This crime was charged ’gainst those who lay

Prisoned in Cuthbert’s islet grey.

Moving back a bit to yesterday’s entry, this is why the abbess of Whitby is going on this journey: to sit in judgement on these attempted murderers.

Sad was this voyage to the dame;

Summoned to Lindisfarne, she came,

There, with Saint Cuthbert’s Abbot old,

And Tynemouth’s Prioress, to hold

A chapter of Saint Benedict,

For inquisition stern and strict,

On two apostates from the faith,

And, if need were, to doom to death.

Lindisfarne is a tidal island: at low tide it is a peninsula that can be reached from the mainland across mudflats, but at high tide it is an island.

The tide did now its floodmark gain,

And girdled in the saint’s domain:

For, with the flow and ebb, its style

Varies from continent to isle;

As the ship reaches Lindisfarne, the nuns of Whitby on the ship sing a hymn, and the nons and monks of Lindisfarne sing one in return.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lindisfarne Priory on the Holy Island of Lindisfarne off northeast England dates back to the 6th century when Celtic Christianity was introduced here. The priory was rebuilt in Norman times after a devastating Viking raid then abandoned in 1537.

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Lindisfarne Castle, Northumberland.

#Lindisfarne Castle#Lindisfarne#Northumberland#north east england#england#britain#islands#castles#beaches#coastline#english coastline

153 notes

·

View notes

Text

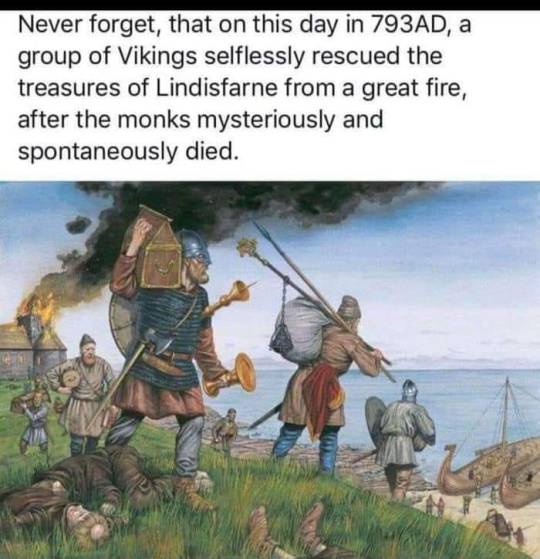

Happy Lindisfarne y'all! 8-6-793

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today is the anniversary of the death of St Cuthbert, celebrated as one of England’s greatest saints, he died on 20th March 687AD.

St Cuthbert was a monk, bishop and hermit of Lindisfarne who lived in Anglo-Saxon Northumbria. A wee bit geography for you, during St Cuthberts time, the area that is now Scotland was divided into three areas: Pictland, a patchwork of small lordships in central Scotland, the Anglo-Saxon Kingdom of Northumbria, which had conquered southeastern Scotland; and the kingdom of Dál Riata in western Scotland. Anglo-Saxon Northumbria stretched from on the East coast, the Humber, where it got it’s name, on the west from the river Mersey, up the the Firth of Forth, and what is now Dumfries and Galloway in the west.

Cuthbert was born (perhaps into a noble family) in Dunbar, now in East Lothian, at the time the region was still largely Pagan, although King Edwin of Northumbria was spreading Christianity having been converted about ten years previously. Incidentally some claim that Edwin might have given Edinburgh it’s name, but it is generally accepted the name derived from the area being known as Eidyn, from the time the Roans left, into the dark ages, the name Eidyn itself’s origin is not known.

Back to oor Cuthbert, he is known to have grown up in what is now The Scottish Borders, we know that he tended sheep on the hills above the abbey at Melrose when he was older.

t seems, from stories about his childhood, that he was brought up as a Christian. He was credited, for instance, with having saved by his prayers, some monks who were being swept out to sea on a raft. There is some evidence that, in his mid-teens, he was involved in at least one battle, which would have been quite normal for a boy of his social background.

His life changed when he was about 17 years old. He was looking after some neighbour’s sheep on the hills. (As he was certainly not a shepherd boy it is possible that he was mounting a military guard - a suitable occupation for a young warrior!) Gazing into the night sky he saw a light descend to Earth and then return, escorting, he believed, a human soul to Heaven. The date was August 31st 651AD - the night that Saint Aidan died. Perhaps Cuthbert had already been considering a possible monastic calling but that was his moment of decision.

He went to the monastery at Melrose, also founded by Aidan, and asked to be admitted as a Novice.

For the next 13 years he was with the Melrose monks. When Melrose was given land to found a new monastery at Ripon, Cuthbert went with the founding party and was made guestmaster. In his late 20s he returned to Melrose and found that his former teacher and friend, the prior Boisil, was dying of the plague. Cuthbert became prior (second to the Abbot) at Melrose.

In 664AD the Synod of Whitby decided that Northumbria should cease to look to Ireland for its spiritual leadership and turn instead to the continent the Irish monks of Lindisfarne, with others, went back to Iona. The abbot of Melrose subsequently became also abbot of Lindisfarne and Cuthbert its prior.

Cuthbert seems to have moved to Lindisfarne at about the age of 30 and lived there for the next 10 years. He ran the monastery; he was an active missionary; he was much in demand as a spiritual guide and he developed the gift of spiritual healing. Cuthbert was said to be an outgoing, cheerful, compassionate person and no doubt became popular. But when he was 40 years old he believed that he was being called to be a hermit and to do the hermit’s job of fighting the spiritual forces of evil in a life of solitude.

After a short trial period on the tiny islet adjoining Lindisfarne he moved to the more remote and larger island known as ‘Inner Farne’ and built a hermitage where he lived for 10 years. Of course, people did not leave him alone - they went out in their little boats to consult him or ask for healing. However, on many days of the year the seas around the islands are simply too rough to make the crossing and Cuthbert was left in peace.

At the age of about 50 it is written that he was asked by both Church and King to leave his hermitage and become a bishop. He reluctantly agreed. For two years he was an active, travelling bishop as Aidan had been. He seems to have journeyed extensively. On one occasion he was visiting the Queen in Carlisle when he knew by second sight that her husband, the King, had been slain by the Picts doing battle in Scotland.

Feeling the approach of death he retired back to the hermitage on the Inner Farne where, in the company of Lindisfarne monks, he died on on this day in 687AD.

His body was brought back and buried on Lindisfarne, well for a time anyway, after long journeys escaping the Danes his remains "chose", as was thought, to settle at Durham, causing the foundation of the city and Durham Cathedral. The St Cuthbert Gospel is among the objects later recovered from St Cuthbert's coffin, which is also an important artefact.

Pics are depictions of Cuthbert, the second featuring his incorrupt body from the Life of Cuthbert, a 12th century manuscript.

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Come back to the Holy Isle of Lindisfarne again. That's the ancient ruins of the priory and inside the new one built behind it. Lindisfarne Castle is in the distance, and that's me with my new drinking horn 😁

For fans of the tv show Vikings, that priory is NOT where Athelstan would have been, the one on the island was built out of wood not stone and the original location of it is long since lost.

Edit:

However this might have been:

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lindisfarne Castle, Holy Island, Northumberland, England

May 28, 2023

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tonight’s Folk Friday earworm: Lindisfarne - Together Forever

Today is Deanne’s and my wedding anniversary!

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The first Viking raid on English soil happened at Lindisfarne in Northumbria in June 793. The attack’s brutality sent shockwaves through Europe and marked the beginning of the Viking Age.

26 notes

·

View notes