#lindy don’t hear this and act silly

Text

“dawson mercer was so excited to play with nico hischier” STOPSJDJSKSNJS

#devs lb#i like this line#i like mercer on this line#i like these guys#lindy don’t hear this and act silly

8 notes

·

View notes

Link

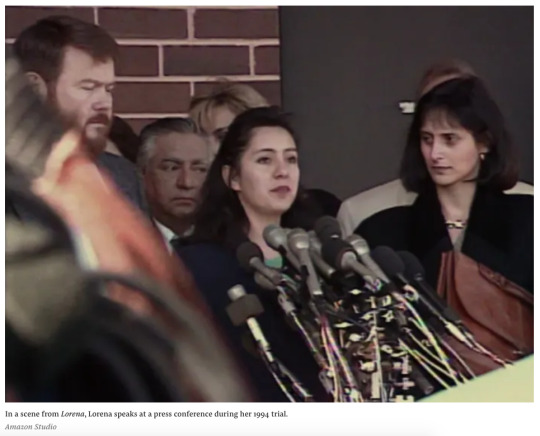

Chances are that you know what made Lorena Bobbitt famous in 1993, even if you aren’t old enough to have experienced it in real time. Just over 25 years ago, Lorena — who now goes by her maiden name, Lorena Gallo — cut her husband’s penis off in the middle of the night, driving away with it and throwing it into a field. The trial and media coverage were sensational, as you might expect them to be around any penis-chopping case — and Lorena’s story became a punchline, an oddity, a way to consider supposedly hotheaded Latina women.

Amazon is now premiering a four-part docuseries about her, aptly called Lorena. The documentary, produced by Jordan Peele, covers the trial, of course, but also explores the context around it that people have largely forgotten, or never learned to begin with: the ways Lorena’s husband, John Wayne Bobbitt, allegedly abused her; the cruel treatment she received from the media, her tender age (she was 24 years old); and how this case brought the issue of marital rape to the forefront for the American public.

The timing is excellent, if a total bummer. The embers of the #MeToo movement are still burning, marital rape continues to be a surprisingly controversial topic for the courts to grapple with, and everyone is still afraid of immigrants. Lorena is compelling and well-made, a narrative that focuses both on the salacious details of the case (wanna see a severed dick? Girl, you got it) and Lorena’s activism in preventing domestic violence and sexual assault. It acts as both a historical primer for those who didn’t live through Lorena’s trial and a rectification for the way she was treated, not just by her husband but by late-night talk show hosts, journalists, and the public. “The media was focusing only on the penis, the sensationalistic, the scandalous. But I wanted to shine the light on this issue of spousal abuse,” Lorena told Vanity Fair in an interview this past summer.

As a documentary that reassesses a notable ’90s scandal with the benefit of a couple decades’ hindsight, Lorena is one among many recent examples. And these retrospectives tend to fit a similar pattern: We are asked or encouraged to reconsider a woman whose public image was linked inextricably with a man’s bad behavior, whose reputation was destroyed while the man got away relatively consequence-free.

2013’s Anita was a reconsideration of Anita Hill’s allegations of sexual harassment against then–Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas. The documentary recast her not as an angry black woman trying to keep a man from his deserved job, but a reserved, smart attorney who merely told the truth about a man about to be given a tremendous amount of power. (Sound familiar?) 2014’s The Price of Gold gave Tonya Harding room to tell her version of the story of her career and the 1994 attack on Nancy Kerrigan, replete with class context and details about her own abuse.

The 2016 documentary O.J. Simpson: Made in America, though primarily about Simpson, also forced audiences to rethink how his murdered ex-wife Nicole Brown Simpson was treated by him and by the press. And 2018’s The Clinton Affair included an interview with Monica Lewinsky herself about her affair with President Bill Clinton — long considered a salacious sexual scandal, with Lewinsky cast as a slut trying to fuck a powerful man — and reframed the incident as one in which a young intern was seduced (and then thrown under the bus) by the goddamn president, who should’ve known better.

These reconsiderations aren’t limited to documentaries. In June, journalist Allison Yarrow published the book ’90s Bitch: Media, Culture, and the Failed Promise of Gender Equality, which includes Hill, Harding, Lewinsky, and Lorena in telling “the real story of women and girls in the 1990s, exploring how they were maligned by the media.” Podcasts like Sarah Marshall and Michael Hobbes’ You’re Wrong About… also serialize reassessments of history, often focusing on women mired in scandals. They’ve done episodes on Amy Fisher (the “Long Island Lolita”), televangelist Tammy Faye Bakker, Lindy Chamberlain-Creighton (the “dingo’s got my baby” woman, who never actually said that), Courtney Love, and Lorena herself.

“America is going through this period of realizing how much we misread what was right in front of us,” says Marshall. “We came to the realization that we elected a reality TV president. We elected someone whose image was made by reality TV. That kind of understanding can allow us to go back and say, “What else did I just swallow that I was sold?”

Documentaries that revisit scandals are no doubt valuable in that they can profoundly change the way we consider the past and hopefully, the future. But they also pose a certain temptation to get too comfortable: There is some risk that we might watch something like Lorena, pat ourselves on the back for figuring out who the bad guy really is, and walk away thinking that the past is the past and we won’t make the same mistakes again. But what Lorena Bobbitt’s story meant in 1993 “is not that different from what it means today,” says journalist Kim Masters in Lorena. “It’s the same story.”

Then, too, there’s the reality that these reconsiderations tend to revolve around trials or public hearings, which provide a clear way to revisit the past through criminal records and court transcripts and recorded interviews. These were big, splashy stories that now get big, splashy reappraisals. But the world is filled with smaller, more mundane injustices and oversights, and most of those who suffer will never make it to court or Congress, or receive a high-profile opportunity to seek vindication.

Watching something like Lorena feels important, but it also feels lousy, because not enough is different now. Reconsiderations like these can’t be antidotes if we ignore the cure — if we continue to dismiss women and other marginalized, vulnerable people when they’re being abused, or taken advantage of, or otherwise maligned. Lorena receives a tremendous amount of empathy in Lorena, as she should. But why can’t we extend that kind of empathy to more people like her today, instead of waiting two and a half decades to rethink how we’ve behaved?

Apology tours for sexual misconduct are practically rote at this point: Transgressors get plenty of airtime to beg for forgiveness for touching butts, to come out of the closet, to recommend a supposedly great pizza dough cinnamon roll recipe. Meanwhile, victims or survivors are largely forgotten after the accusation becomes public. It’s relatively new that women like Lorena or Hill are getting some space to tell their stories on their own terms, and still rare that the opportunity is afforded to women of color in particular.

Lorena is timely not only in the sense that conversations about sexual abuse and assault have taken center stage over the past year, but also because anxiety about immigrants taking advantage of the system and of poor, unwitting white Americans is currently at a fever pitch. When Lorena and John Wayne Bobbitt got married in 1989, she was 20, and in the US on a student visa. “There’s women who are opportunists, gold diggers, they use you as a stepping stone to advance their career,” Bobbitt says, referring to his ex-wife in an interview in Lorena. “These women, they know that their backup is [to] use law enforcement to their advantage by saying, ‘You know what, if you leave or you fuck up this relationship or you don’t get my citizenship, I’ll call the cops.’”

Despite Bobbitt’s own laundry list of arrests — many of which are for domestic violence against past partners — he still uses Lorena’s citizenship (or lack thereof) as supposed proof that she was unstable, demanding, and manipulative. “She was obsessed with having her American dream, her American dream, her American dream,” Bobbitt told Vanity Fair. “She just wanted too much, too fast.” And even in a supposedly silly reality series like 90 Day Fiancé (a show about bad American people marrying other, noncitizen but still-often-bad people), it’s clear that many of the same biases against immigrants that were at play in the Bobbitt case are alive and well today.

Lorena takes great pains to draw similarities between then and now, reminding viewers that domestic violence is still a secret shame for countless women, and that it’s still incredibly challenging to get away from your abuser. The last episode of the series is called “The Cycle of Abuse” and opens with a slideshow of women’s bruises and scars from domestic violence. “This is about a victim and a survivor and this is about what’s happening in our world today,” Lorena recently told the New York Times.

And that may be true of what Lorena experienced at the hands of the media, as well as her husband. “If Lorena’s story hit today, Fox News would take the place of Howard Stern, and the 24-hour news cycle would focus on what she did, rather than what he did,” says Kim Gandy, the president of the National Network to End Domestic Violence. Documentaries like Lorena are timely for a reason — a bad reason — and instead of feeling smug for finally listening, 25 years later, it’s worth taking the opportunity to see what we can do better now.

While the outrage around Brett Kavanaugh’s confirmation to the Supreme Court this past fall might have sounded deafening depending on who’s inside your political bubble, the result is ultimately the same as it was for Clarence Thomas after Anita Hill’s testimony. He’s in, and there’s nothing anyone can do about it. Meanwhile, Christine Blasey Ford, the woman who came forward to detail Kavanaugh’s alleged assault, was left unable to work and in need of a security detail.

I was 3 years old during Lorena Bobbitt’s trial. I was 7 during the Clinton–Lewinsky scandal. I was a few months old for Anita Hill’s hearing. When Blasey Ford testified late last year, I was 27. And yet somehow her testimony still felt like unbearable déjà vu, as if I had lived through this already and already knew the inevitable conclusion.

Today, though entertainment industry figures like Harvey Weinstein and Les Moonves are facing some long-overdue music for accusations of sexual assault and harassment, it’s taken decades for that to happen. For figures like Bryan Singer and R. Kelly — both the subject of recent reporting that details sexual abuse allegations stretching back many years, both of whom continue to deny any wrongdoing — it remains to be seen what lasting consequences, if any, they will suffer. Their accusers, like Lorena, have been vulnerable people from already marginalized groups — in these cases young, primarily queer boys and black girls — who have been either painted as liars and manipulators or outright dismissed.

What’s upsetting about these stories is not just the abuses they describe, but the public indifference they often get in response; the rumors and allegations around Kelly, for example, have done astonishingly little to tarnish his celebrity or dim public affection until very recently, following the release of the Lifetime documentary series Surviving R. Kelly. And it’s taken 10 years since Michael Jackson’s death for a significant documentary about the allegations of child molestation against him, HBO’s Leaving Neverland, to crack through the surface.

Ten or 20 years from now, will we be watching a heartbreaking five-part docuseries on the alleged victims of Bryan Singer? On the many accusations against him, on how they were ignored for years, on how they sort of broke through in early 2019, how they quickly petered out, and how he continued to get work — and watch his movies win awards — even after the allegations were made public? (Hopefully not.) Is years or decades of hindsight the only way any of us can begin talking about things like domestic violence or sexual assault? The distance might make it feel safer to discuss, especially when powerful people are involved, but it also means the conversation starts far too late.

Lorena also reminds audiences that she was the subject of wild cruelty from the media and comedians during and after her trial. “David Letterman used to call me his girlfriend,” Lorena says in the docuseries. “The jokes did bother me, because I didn’t know to handle it. People were talking about my background. They were saying I was just a hot-blooded Latina woman. It hurts my heart. It hurts my brain. It hurts my whole body.”

Howard Stern practically made a career out of promoting Lorena’s ex-husband — he had Bobbitt on his show repeatedly and during his 1994 Rotten New Year’s Eve Pageant special, raising money for Bobbitt’s medical expenses. During the pageant, Stern airs a mocking reenactment of Lorena’s crime. “A penis is a terrible thing to waste,” Stern says, holding two pieces of a fake member, cut in half, aloft. The Bee Gees performed a parody song that included the advice “Don’t ever piss off your wife.” The metaphor is so blatant it’s embarrassing: A man’s penis is his power, and this woman had the audacity to try to take it away. She needed to be put in her place. “To me it was just cruel,” Lorena told the New York Times. “Why would they laugh about my suffering?”

In hindsight, jokes like these may seem to be in such bad taste that it’s a wonder Stern still has a career. But jokes at the expense of victims and marginalized people haven’t gone away, and neither have most of the comedians who make them. Amy Schumer used to crack jokes about Mexicans being rapists; she apologized for it years later. Sarah Silverman did blackface in 2007; it took her until 2015 to apologize for it (sort of??). Louis C.K. is, currently, mocking the Parkland shooting survivors and joking about his history of masturbating in front of nonconsenting women, all to applause from comedy club audiences. Every Saturday, Michael Che and Colin Jost turn Saturday Night Live into a Statler and Waldorf sketch where they complain about having to learn a few new gender pronouns. None of this will age well, but even in the moment, plenty of us don’t find these “jokes” all that funny to begin with.

The only tangible thing to learn from watching Lorena, besides the full facts of her case, is that the strongest advantage people like Lorena have on their side is time. You just have to wait. You have to wait out the cruel late-night jokes and the sexist media coverage about you and the gossip and conjecture and slut-shaming and mockery. You have to wait two and a half decades, and then maybe, if your case was a big enough deal, someone will make a movie about you, and you’ll get a chance to wear a nice blouse and trousers and sit on a couch and tell your story from the beginning, without interruption, for the first time in your life. The world will turn in your direction, and your abusers will look worse and worse with every passing day (even if they’ve evaded any concrete kind of consequences), but first — you have to wait.

Scandalous stories like Lorena’s are also undoubtedly complicated by the fact that they don’t only boil down to a bad man and a woman wronged. Even in light of widely publicized and well-produced reconsiderations, not all viewers will be on board with Lorena, who did commit a crime, just as Lewinsky is far from a fully redeemed figure now in the public eye. And both women will always be punchlines to some people; even for the few who do get their turn to reframe the stories of their own lives, not everyone is going to listen.

“We always want to find a victim, a villain, and a hero,” says Marshall. “We accept the story we’re told. Having everyone filed away as a certain kind of person and every event filed away as a certain kind of story is how we impose order in the world.” But if you’re able to turn away from that tidy story, and hear what the people who lived it are really saying, “you get closer to the truth.” ●

CORRECTION

February 19, 2019, at 6:34 p.m.

The name of the Michael Jackson HBO documentary Leaving Neverland was misstated in an earlier version of this post.

98 notes

·

View notes

Text

YOU’RE A SAP, MISTER JAP

When Japan attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7 1941, Tin Pan Alley’s songwriters reacted with instant fury and patriotic zeal, churning out hundreds of war songs at a ferocious clip. Amateurs jumped into the fray as well. By December 20, just two weeks later, The Billboard was already reporting that music publishers had received more than one thousand war song submissions. Only a fraction were ever published and recorded, but even that amounted to a lot of records, and a few would have big impacts on American morale early in the war.

The hive of most of that activity was the Brill Building on the west side of Broadway between 49th and 50th Streets. At the start of the century, when the term “Tin Pan Alley” was coined, the music business was concentrated on West 28th Street between Fifth and Sixth Avenues, with Broadway cutting diagonally through. Its nickname referred to the constant racket of cheap upright pianos where guys stacked five stories high toiled long into the night banging out a cacophony of competing tunes. By 1941 most of the publishers had migrated uptown to the eleven-story Brill Building, opened in 1931. Lindy’s, immortalized by Damon Runyon as Mindy’s, was across Broadway.

The first two Tin Pan Alley songs reacting to Pearl Harbor — “We’ll Knock the Japs Right into the Laps of the Nazis” and “We Did It Before (and We Can Do It Again)” — were allegedly written that very day, December 7. Hearing the news from Hawaii, composer Lew Pollack and lyricist Ned Washington whipped out “We’ll Knock the Japs” on Sunday afternoon and rushed it to Bert Wheeler, of the vaudeville and Broadway comedy duo Wheeler & Woolsey. (Woolsey had died in 1938.) Wheeler apparently introduced the song that night as part of his club act in Los Angeles. In part it went:

Oh, we didn't want to do it but they're asking for it now

So we'll knock the Japs right into the laps of the Nazis,

When they hop on Honolulu that's a thing we won't allow

So we'll knock the Japs right into the laps of the Nazis!

Chins up, Yankees, let's see it through,

And show them there's no yellow in the red, white and blue

I'd hate to be in Yokohama when our bombers make their bow,

For we'll knock the Japs right into the laps of the Nazis!

Also on Sunday, another pair of Tin Pan Alley stalwarts, Charles Tobias and Cliff Friend, knocked out “We Did It Before,” a rousing George M. Cohan–style march. Friend is best known now for having written the theme song for Looney Tunes (“The Merry-Go-Round Broke Down”) in 1937. Tobias’s long list of credits includes “Those Lazy-Hazy-Crazy Days of Summer,” “Merrily We Roll Along” — which he cowrote with his brother-in-law Eddie Cantor, and which Warner Bros. adapted for its Merrie Melodies theme song — as well as one that became a huge hit during the war, “Don’t Sit Under the Apple Tree (With Anyone Else but Me).”

Cantor introduced “We Did It Before” on his popular weekly radio show that Wednesday, December 10. Dinah Shore sang it on her radio show the following Sunday, and Cantor went on to interpolate it into his stage revue Banjo Eyes, which opened on Broadway on Christmas Day and ran into April 1942. The sheet music was a top ten seller for a couple of months. Bringing things full circle, in 1943 Warner Bros. would use the song in a Merrie Melodies cartoon, Fifth Column Mouse, in which the mice mobilize for war against a dictatorial cat.

By Monday morning, December 8, the Tin Pan Alley trio of lyricist James Cavanaugh (best known for “You’re Nobody till Somebody Loves You”), John Redmond, and Nat Simon had written the upbeat “You’re a Sap, Mr. Jap”:

You’re a sap, Mr. Jap, you make a Yankee cranky,

You’re a sap, Mr. Jap, Uncle Sam is gonna spanky

It was released as a single before the month was out. In 1942 it also found its way into a cartoon, the first Popeye cartoon of the war, with caricatures of Japanese that were so extreme it was removed from circulation after the war — along with a number of other patriotically racist cartoons — and rarely seen again until the birth of the Internet.

By the week of January 11 Billboard counted twenty-four war singles released since December 7. There was the catchy “Goodbye Mama, I’m Off to Yokohama,” written by Brooklyn-born J. Fred Coots, better known for writing “Santa Claus Is Coming to Town” in 1934. The singer of this song was going to “teach all those Japs / The Yanks are no saps.”

Kate Smith weighed in with the spritely “They Started Somethin’ (But We’re Gonna End It)” and the sentimental ballad “Dear Mom,” a soldier’s letter home. She would follow them in February with “This Time,” a not particularly memorable Irving Berlin number. (“We’ll fight to the finish this time / Then we’ll never have to do it again.”) Billboard listed three different recordings of the inevitable “Remember Pearl Harbor,” plus the clever “Let’s Put the Axe to the Axis” and the swinging “The Sun Will Soon Be Setting (For the Land of the Rising Sun).”

The list also included two interesting “hillbilly” songs, as country music was then called. They emanated not from Nashville but the Brill Building. Tin Pan Alley had been exploring the relatively small markets for hillbilly and folk music since the 1920s. Then the genres got a boost in popularity in 1941 from an unlikely source. In January, ASCAP (American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers), the professional organization that licensed music to the radio broadcasters, demanded a doubling in fees. Broadcasters responded by pulling all ASCAP music from the airwaves and plugged the gap with music by non-ASCAP members, especially hillbilly and folk. By October, when ASCAP and the broadcasters came to new terms, hillbilly and folk had expanded their niche in the market, and the Tin Pan Alley pros cashed in.

One of those pros was Fred Rose, whose “Cowards Over Pearl Harbor” was a mournful, guitar-strumming folk ballad recorded by Denver Darling. Two of the most prolific were Memphis-born Bob Miller and Kansas-born Carson Robison, who both came to Tin Pan Alley in the 1920s. Miller worked for a while as Irving Berlin’s arranger, while Robison specialized in country and cowboy songs that humorously treated topical themes. Their response to Pearl Harbor was the outrageous “We’re Gonna Have to Slap the Dirty Little Jap,” sung to a silly, quick-time oompah melody:

We're gonna have to slap the dirty little Jap

And Uncle Sam's the guy who can do it

We'll skin the streak of yellow from this sneaky little fellow

And he'll think a cyclone hit him when he's through it

We'll take the double crosser to the old woodshed

We'll start on his bottom and go to his head

When we get through with him he'll wish that he was dead

We gotta slap the dirty little Jap

We're gonna have to slap the dirty little Jap

And Uncle Sam's the guy who can do it

The Japs and all their hooey will be changed into chop suey

And the rising sun will set when we get through it

Their alibi for fighting is to save their face

For ancestors waiting in celestial space

We'll kick their precious face down to the other place

We gotta slap the dirty little Jap

Robison went on to record several more humorous war songs, including “Mussolini’s Letter to Hitler” and its flip side “Hitler’s Reply to Mussolini,” “Get Your Gun and Come Along (We’re Fixin to Kill a Skunk),” and “Who’s Gonna Bury Hitler (When the Ornery Cuss Is Dead)?”

Far and away the most successful song responding to Pearl Harbor was Frank Loesser’s “Praise the Lord and Pass the Ammunition,” one of the biggest hits of 1942. Born into a wealthy Upper West Side Jewish household, Loesser had dismayed his family when he went first to Tin Pan Alley and then to Hollywood, where he wrote the lyrics for such standards as “Heart and Soul,” “Baby, It’s Cold Outside,” and “Two Sleepy People.” “Praise the Lord” was inspired by a Pearl Harbor legend concerning the fleet chaplain (“sky pilot” in the song) Father William A. Maguire, who helped carry ammo to the guns firing at the attacking planes and supposedly cried out the song’s title. Father Maguire told Life he didn’t remember saying the line and it would not have been heard in all the uproar even if he did, but you can’t stop a legend. In some versions — including Loesser’s — Maguire actually manned a gun himself.

First recorded by the vocal quartet the Merry Macs, then by Kay Kyser and others, “Praise the Lord” sold huge numbers in both disc and sheet music, nearly matching Irving Berlin’s giant “White Christmas” in sales and jukebox plays for a time. No doubt much of its popularity stemmed from its easy-to-sing simplicity, with lyrics that weren’t much more than the title repeated over and over to a strolling melody that sounded like an old-time spiritual.

Loesser donated his proceeds from the song to the U.S. Navy Relief Fund. After the war he would have a big Broadway hit with Guys and Dolls.

by John Strausbaugh

Excerpted from John's new book Victory City: A History of New York and New Yorkers During World War II.

0 notes

Note

part1) This Mongolia deal has gone on so long I can't remember if I actually typed it out loud or deleted it, but I said waaay back around episode 6 or so that the only thing that makes sense with the way things came unraveled with the story this year was either someone had a serious illness or there was some sort of a contract dispute, and I had no idea back then that the Mongolia thing would drag on like it eventually did. It was obvious that Michelle was looking for something else (cont)

to do when all those photo shoot head shots started showing up on her social media accounts. I watched her Christmas movie and I hear there are other things she did, so don't make the mistake of thinking it was all about her family. Wardle has kept the fans in the dark so, what we know is all we know about that. Like I have said before, it is their life to live and if they choose to do something else, so be it and I wish them well, but the least they could do is quit jerkingus loyal fans around with making the writers pull a miracle plot out of their ass every time one of them pulls the disappearing act on us. I empathize with the writers and their dilemma of the way things have gone with production this year. How can you tell a story when most of your cast is unavailable? I chose to skip the most of this season until I can binge watch and 'get it over with" without having to agonize days between waiting for nothing to happen for most of the season.I know this is a pretty abrasive reaction from me, especially for those who know me at least a little, but enough is enough. There are so many good stories to draw from, such as what really happened with Lindy's illness, filling in Lisa's backstory and business dealings, how did Mitch get to be who he is and what kind of guy is he really, (with Lou or without her), and where is Scott and what has he been up to? There's a million questions about Caleb and Cass to be exploredand bring in more guests with an interesting problem or agenda if a steady cast is too expensive to maintain. There are a lot of arcs out there waiting to be developed which could be pleasantly entertaining. I hope we get to see that kind of commitment from key people in this production from now on, not more silly distractions to cover up whatever has been driving things off the rails the past couple of seasons. Bill Sims, we miss your input right about now. - Steve

2 notes

·

View notes