#look at that John Cassavetes quote

Text

“At times Mikey treats Nicky like a son (‘Open the door,’ he soothingly says as he tries to feed Nicky an antacid tablet).

“At other times they tease each other like brothers.

“And then there is the touching moment when a distraught Nicky leans into Mikey, and Mikey massages the back of his neck with the gentleness of a lover.”

Mikey and Nicky (1976) dir. elaine may

#I don’t think I’ll ever recover from this movie#falk and cassavetes are absolutely amazing actors#I’m looking forward to watching more of their movies#mikey and nicky#elaine may#Peter falk#john cassavetes#mikey and nicky 1976#the quote is an excerpt from an article from Larsen on Film about Mikey and Nicky

104 notes

·

View notes

Text

Taylor going to Tribeca and now TIFF film festival with All Too Well’s short film makes me think a couple of things; she’s never been prouder of anything she’s made, she’s deadly serious about getting that Oscar shortlist/nomination spot, she thrives on being asked about her art and the process of creating and that there are indeed more films coming - although not necessarily drawing inspiration from her songs as directly. We should be prepared to hear a lot more from director/screenwriter Taylor

#taylor swift#all too well short film#tiff 2022#I just know there’s more coming#look at that John Cassavetes quote#hannah post™️#director taylor swift

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

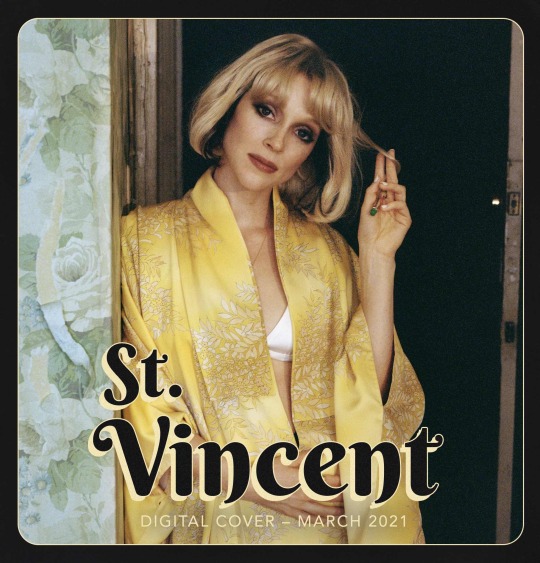

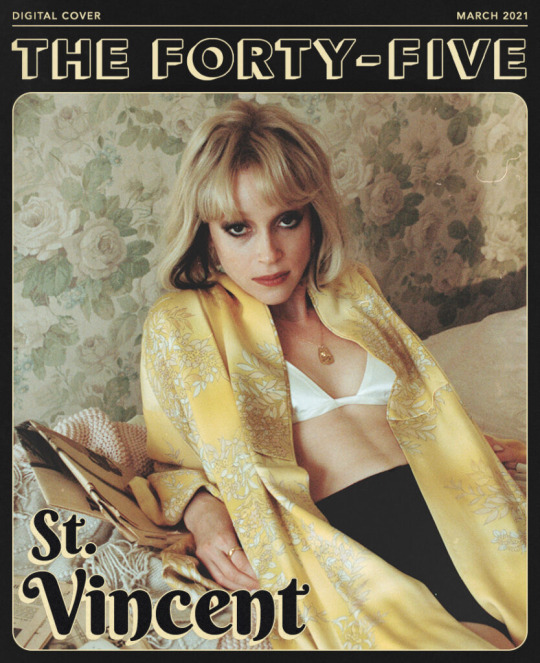

THE FORTY-FIVE: ST. VINCENT

Sleazy, gritty, grimy – these are the words used to describe the latest iteration of St. Vincent, Annie Clark’s alter ego. As she teases the release of her upcoming new album, ‘Daddy’s Home’, Eve Barlow finds out who’s wearing the trousers now.

Photos: Zackery Michael

Yellow may be the colour of gold, the hue of a perfect blonde or the shade of the sun, but when it’s too garish, yellow denotes the stain of sickness and the luridness of sleaze. On ‘Pay Your Way In Pain’ – the first single from St. Vincent’s forthcoming sixth album ‘Daddy’s Home’ – Annie Clark basks in the palette of cheap 1970s yellows; a dirty, salacious yellow that even the most prudish of individuals find difficult to avert their gaze from. It’s a yellow that recalls the smell of cigarettes on fingers, the tape across tomorrow’s crime scene or the dull ache of bad penetration.

The video for the single, which dropped last Thursday, features Clark in a blonde wig and suit, channeling a John Cassavetes anti-heroine (think Gena Rowlands in Gloria) and ‘Fame’-era Bowie. She twists in front of too-bright disco lights. She roughs up her voice. She sings about the price we pay for searching for acceptance while being outcast from society. “So I went to the park just to watch the little children/ The mothers saw my heels and they said I wasn’t welcome,” she coos, and you immediately recognise the scene of a free woman threatening the post-nuclear families aspiring to innocence. Clark is here to pervert them.

She laughs. “That’s how I feel!” From her studio in Los Angeles, she begins quoting lyrics from Jimi Hendrix’s ‘Red House’. “It’s a blues song for 2021.” LA is a city Clark reluctantly only half calls home, and one that is opposed to her vastly preferred New York. “I don’t feel any romantic attachment to Los Angeles,” she says of the place she coined the song ‘Los Ageless’ about on 2017’s ‘Masseduction’ (“The Los Ageless hang out by the bar/ Burn the pages of unwritten memoirs”).“The best that could be said of LA is, ‘Yeah it’s nice.’ And it is! LA is easy and pleasant. But if you were a person the last thing you’d want someone to say about you is: ‘She’s nice!’”

On ‘Daddy’s Home’, Clark writes about a past derelict New York; a place Los Angeles would suffocate in. “The idea of New York, the art that came out of it, and my living there,” she says. “I’ve not given up my card. I don’t feel in any way ready to renounce my New York citizenship. I bought an apartment so I didn’t have to.” Her down-and-out New York is one a true masochist would love, and it’s sleazy in excess. Sleaze is usually the thing men flaunt at a woman’s expense. In 2021, the proverbial Daddy in the title is Clark. But there’s also a literal Daddy. He came home in the winter of 2019.

On the title track, Clark sings about “inmate 502”: her father. He was sentenced to 12 years in prison for his involvement in a $43m stock fraud scheme. He went away in May 2010. Clark reacted by writing her third breakthrough album ‘Strange Mercy’ in 2011; inspired not just by her father’s imprisonment but the effects it had on her life.“I mean it was rough stuff,” she says. “It was a fuck show. Absolutely terrible. Gut-wrenching. Like so many times in life, music saved me from all kinds of personal peril. I was angry. I was devastated. There’s a sort of dullness to incarceration where you don’t have any control. It’s like a thud at the basement of your being. So I wrote all about it,” she says.

Back then, she was aloof about meaning. In an interview we did that year, she called from a hotel rooftop in Phoenix and was fried from analytical questions. She excused her lack of desire to talk about ‘Strange Mercy’ as a means of protecting fans who could interpret it at will. Really she was protecting an audience closer to home. It’s clear now that the title track is about her father’s imprisonment (“Our father in exile/ For God only knows how many years”). Clark’s parents divorced when she was a child, and they have eight children in their mixed family, some of whom were very young when ‘Strange Mercy’ came out. She explains this discretion now as her method of sheltering them.

“I am protective of my family,” she says. “It didn’t feel safe to me. I disliked the fact that it was taken as malicious obfuscations. No.” Clark wanted to deal with the family drama in art but not in press. She managed to remain tight-lipped until she became the subject of a different intrusion. As St. Vincent’s star continued to rocket, Clark found herself in a relationship with British model Cara Delevingne from 2014 to 2016, and attracted celebrity tabloid attention. Details of her family’s past were exposed. The Daily Mail came knocking on her sister’s door in Texas, where Clark is from.

“Luckily I’m super tight with my family and the Daily Mail didn’t find anybody who was gonna sell me out,” she says. “They were looking for it. Clark girls are a fucking impenetrable force. We will cut a bitch.”

Four years later, Clark gets to own the narrative herself in the medium that’s most apt: music. “The story has evolved. I’ve evolved. People have grown up. I would rather be the one to tell my story,” she says, ruminating on the misfortune that this was robbed from her: a story that writes itself. “My father’s release from prison is a great starting point, right?” Between tours and whenever she could manage, Clark would go and visit him in prison and would be signing autographs in the visitation room for the inmates, who all followed her success with every album release, press clipping and late night TV spot. She joked to her sisters that she’d become the belle of the ball there. “I don’t have to make that up,” she says.

There’s an ease to Clark’s interview manner that hasn’t existed before. She seems ready not just to discuss her father’s story, but to own certain elements of herself. “Hell where can you run when the outlaw’s inside you,” she sings on the title track, alluding to her common traits with her father. “I’ve always had a relationship with my dad and a good one. We’re very similar,” she says. “The movies we like, the books, he liked fashion. He’s really funny, he’s a good time.” Her father’s release gave Clark and her brothers and sisters permission to joke. “The title, ‘Daddy’s Home’ makes me laugh. It sounds fucking pervy as hell. But it’s about a real father ten years later. I’m Daddy now!”

The question of who’s fathering who is a serious one, but it’s also not serious. Clark wears the idea of Daddy as a costume. She likes to play. She joins today’s Zoom in a pair of sunglasses wider than her face and a silk scarf framing her head. The sunglasses come off, and the scarf is a tool for distraction. She ties it above her forehead, attempts a neckerchief, eventually tosses it aside. Clark can only be earnest for so long before she seeks some mischief. She doesn’t like to stay in reality for extensive periods. “I like to create a world and then I get to live in it and be somebody new every two or three years,” she says. “Who wants to be themselves all the time?”

‘Daddy’s Home‘ began in New York at Electric Lady studios before COVID hit and was finished in her studio in LA. She worked on it with “my friend Jack” [Jack Antonoff, producer for Lana Del Rey, Lorde, Taylor Swift]. Antonoff and Clark worked on ‘Masseduction’ and found a winning formula, pushing Clark’s guitar-orientated electronic universe to its poppiest maximum, without compromising her idiosyncrasies. “We’re simpatico. He’s a dream,” she says. “He played the hell outta instruments on this record. He’s crushing it on drums, crushing it on Wurlitzer.” The pair let loose. They began with ‘The Holiday Party’, one of the warmest tracks Clark’s ever written. It’s as inviting as a winter fireplace, stoked by soulful horns, acoustic guitar and backing singers. “Every time they sang something I’d say, ‘Yeah but can you do it sleazier? Make your voice sound like you’ve been up for three days.” Clark speaks of an unspoken understanding with Antonoff as regards the vibe: “Familiar sounds. The opposite of my hands coming out of the speaker to choke you till you like it. This is not submission. Just inviting. I can tell a story in a different way.”

The entire record is familiar, giving the listener the satisfaction that they’ve heard the songs before but can’t quite place them. It’s a satisfying accompaniment to a pandemic that encouraged nostalgic listening. Clark was nostalgic too. She reverted to records she enjoyed with her father: Stevie Wonder’s catalogue from the 1970s (‘Songs In The Key Of Life’, ‘Innervisions’, ‘Talking Book’) and Steely Dan. “Not to be the dude at the record store but it’s specifically post-flower child idealism of the ’60s,” she explains. “It’s when it flipped into nihilism, which I much prefer. Pre disco, pre punk. That music is in me in a deep way. It’s in my ears.”

On ‘The Melting Of The Sun’ she has a delicious time creating a psychedelic Pink Floyd odyssey while exploring the path tread by her heroes Marilyn Monroe, Joni Mitchell, Joan Didion and Nina Simone. It’s a series of beautiful vignettes of brilliant women who were met with a hostile environment. Clark considers what they did to overcome that. “I’m thanking all these women for making it easier for me to do it. I hope I didn’t totally let them down.” Clark is often the only woman sharing a stage with rock luminaries such as Dave Grohl, Damon Albarn and David Byrne, and has appeared to have shattered a male-centric glass ceiling. She’s unsure she’s doing enough to redress the imbalance. “There are little things I can do and control,” she says of hiring women on her team. “God! Now I feel like I should do more. What should I do? It’s a big question. You know what I have seen a lot more from when I started to now? Girls playing guitar.”

If one woman reinvented the guitar in the past decade, it’s Clark. Behind her is a rack of them. The pandemic has taken her out of the wild in which she’s accustomed to tantalising audiences at night with her displays of riffing and heel-balancing. Instead, she’s chained to her desk. Her obsession with heels in the lyrics of ‘Daddy’s Home’ she reckons may be a reflection of her nights performing ‘Masseduction’ in thigh highs. “I made sure that nothing I wore was comfortable,” she recalls. “Everything was about stricture and structure and latex. I had to train all the time to make sure I could handle it.” Is she taking the heels off when live shows return? “Absofuckinglutely not.”

Clark is interested in the new generation. She’s recently tweeted about Arlo Parks and has become a big fan of Russian singer-songwriter Kate NV. “I’m obsessed with Russia,” she says. In a recent LA Times profile, she professed to a pandemic intellectual fixation on Stalin. “Yeah! I mean right now my computer is propped up on stuff. You are sitting on The Gulag Archipelago, The Best Short Stories Of Dostoyevsky andThe Plays Of Chekhov. I’m kinda in it.” The pop world interests Clark, too. She was credited with a co-write on Swift’s 2019 album ‘Lover’. At last year’s Grammys she performed a duet with Dua Lipa. It was one of the queerest performances the Grammys has ever aired. Clark interrupts.

“What about it seemed queer?!”

You know… The lip bite, for one!

“Wait. Did she bite her lip?”

No, you bit your lip.

“I did?!”

Everyone was talking about it. Come on, Annie.

“Serious? I…”

You both waltzed around each other with matching hairdos, making eyes…

“I have no memory of it.”

Frustrating as it may be in a world of too much information, Clark’s lack of willingness to overanalyse every creative decision she makes or participates in is something to treasure. “I want to be a writer who can write great songs,” she says. “I’m so glad I can play guitar and fuck around in the studio to my heart’s desire but it’s about what you can say. What’s a great song? What lyric is gonna rip your guts open. Just make great shit! That’s where I was with this record. That’s all I wanna do with my life.”

More than a decade into St. Vincent, Clark doesn’t reflect. She looks strictly forward. “I’m like a horse with blinders,” she says. She did make an exception to take stock lately when the phone rang. “I saw a +44 and that gets me excited,” she says. “Who could this be?” Well, who was it? “Paul McCartney,” she says, in disbelief. “Anything I’ve done, any mistake I’ve made, somehow it’s forgiven, assuaged. I did something right in my life if a fucking Beatle called me.”

Now there’s a get out of jail free card if ever she needed one.

Daddy’s Home by St. Vincent is out May 14, 2021.

#‘I HAVE NO MEMORY OF IT’#LOOOOOL#WHY ARE U LIKE THIS#st vincent#full of shit#annie clark#Annie Clark on beds#yellow is the color for dull ache of bad penetration?

68 notes

·

View notes

Note

What is your favorite Cassavetes movie and why? Do you have a favorite falksavettes moment?

well HELLO!! i think my favourite Cassavates movie is Opening Night. incredible experience. a total masterpiece. Gena Rowlands invented acting and this movie is a love letter to her and theatre.

for my favourite falksavetes moments, the whole dick cavett interview is definitely up there [”don’t tell him the true nature of our relationship.” “why not? you find it damaging?” “yes.” “alright i won’t”]. You can look through my john & peter tag, its all fave moments tbh, but here is a quote that makes me insane.....

#john accepting to direct one last film despite his health just because peter asked him....is also...quite Up There#thank you anon <3#peter talking about john is always a tear making moment#add gena talking with him to the mix and im in SHAMBLES baby#john cass#ask

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Border Radio”: Where Punk Lived

Some years back, I wrote notes for the Criterion Collection’s edition of Allison Anders’ first feature Border Radio for the Criterion Collection. Tomorrow (June 3), Allison will gab about punk rock with John Doe, Tom DeSavia, and my illegitimate son Keith Morris at the Grammy Museum in L.A. in observance of the publication of the book we’re all in, More Fun in the New World (Da Capo).

**********

“You can’t expect other people to create drama for your life—they’re too busy creating it for themselves,” a punk groupie says at the conclusion of Border Radio. And the four reckless characters at the center of the film certainly manage to create plenty of drama for themselves. In the process, they paint a compelling picture of the Los Angeles punk-rock scene of the 1980s: what it was like on the inside—and what it was like inside the musicians’ heads.

Border Radio (1987) was the first feature by three UCLA film students: Allison Anders, Kurt Voss, and Dean Lent. The subsequent work of both Anders and Voss would resonate with echoes from Border Radio and its musical milieu. Anders’s Gas Food Lodging (1992), Mi vida loca (1993), Grace of My Heart (1996), Sugar Town (1999), and Things Behind the Sun (2001) all draw to some degree from music and pop culture. (She quotes her mentor Wim Wenders’s remark about making The Scarlet Letter: “There were no jukeboxes. I lost interest.”) Voss, who co-wrote and codirected Sugar Town, also wrote and directed Down & Out with the Dolls (2001), a fictional feature about an all-girl band; and in 2006, he was completing Ghost on the Highway, a documentary about Jeffrey Lee Pierce, the late vocalist for the key L.A. punk group the Gun Club.

The three filmmakers met at UCLA in the early eighties, after Anders and Voss had worked as production assistants on Wenders’s Paris, Texas. By that time, Anders and Voss, then a couple, were habitués of the L.A. club milieu; they favored the hard sound of such punk acts as X, the Blasters, the Flesh Eaters, the Gun Club, and Tex & the Horseheads. The neophyte writer-directors, who by 1983 had made a couple of short student films, formulated the idea of building an original script around a group of figures in the L.A. punk demimonde.

Border Radio—which takes its title, and no little script inspiration, from a Blasters song (sung on the soundtrack by Rank & File’s Tony Kinman)—was conceived as a straight film noir. Vestiges of that origin can be seen in the finished film. Its lead character bears the name Jeff Bailey, also the name of Robert Mitchum’s doomed character in Jacques Tourneur’s 1947 noir Out of the Past; its Mexican locations also reflect a key setting in that bleak picture. One sequence features a pedal-boat ride around the same Echo Park lagoon where Jack Nicholson’s J. J. Gittes does some surveillance in Roman Polanski’s 1974 neonoir Chinatown; Chinatown itself—a hotbed of L.A. punk action in the late seventies and early eighties—features prominently in another scene. Certainly, Border Radio’s heist-based plot and the multiple betrayals its central foursome inflict upon each other are the stuff of purest noir. But the film diverges from its source in its largely sunlit cinematography and its explosions of punk humor; Anders, Voss, and Lent also abandoned plans to kill off the film’s lead female character.

In casting their feature, the filmmakers turned to some able performers who were close at hand. The female lead was taken by Anders’s sister Luanna; her daughter was portrayed by Anders’s daughter Devon. Chris, Jeff’s spoiled, untrustworthy friend and roadie, was played by UCLA theater student Chris Shearer.

The directors considered another student for the lead role of the tormented musician, Jeff, but Anders, in an inspired stroke, suggested Chris D. (né Desjardins), whose brooding, feral presence animated the Flesh Eaters. After being approached at a West L.A. club gig and initially expressing surprise at the filmmakers’ desire to cast him, the singer and songwriter signed on, and he helped recruit the other musicians in Border Radio. (A cineaste whose criticism often appeared in the local punk rag Slash, Desjardins would later write an authoritative book on Japanese yakuza films and write and direct the independent vampire film I Pass for Human. He is currently a programmer at the Los Angeles Cinematheque.)

John Doe, bassist-vocalist for the celebrated L.A. punk unit X, and Dave Alvin, guitarist and songwriter for the top local roots act the Blasters, had both played with Chris D. in an edition of the Flesh Eaters. Doe—taking the first in a long list of film and TV roles—was cast as the duplicitous, drunken rocker Dean; Alvin makes an entertaining cameo appearance, essentially as himself, and wrote and performed the film’s score.Texacala Jones, frontwoman for the chaotic Tex & the Horseheads, does a hilarious turn as Devon’s addled babysitter. Iris Berry, later a member of the raucous all-female group the Ringling Sisters, portrays the self-absorbed groupie whose observations frame the film.

Julie Christensen, Desjardins’ vocal partner in his latter-day group Divine Horsemen (and, for a time, his wife), essays a bit part as a club doorwoman. Seen in walk-ons are such local rockers as Tony Kinman, Flesh Eaters bassist Robyn Jameson, and punk hellion Texas Terri. The Arizona “paisley underground” transplants Green on Red and the local glam-punk outfit Billy Wisdom & the Hee Shees were captured in live performance. Those seeking punk verisimilitude could ask for nothing more.

Border Radio had a torturous, piecemeal production history worthy of John Cassavetes. Shooting took place over a four-year period, from 1983 to 1987. Begun with two thousand dollars in seed money, supplied by actor Vic Tayback, the film scraped by on money given to Voss upon his 1984 graduation from UCLA, a loan from Lent’s parents, and cash and film stock cadged here and there. Violating UCLA policy, the filmmakers cut the film at night in the school’s editing bays, where Anders’s two young daughters would sleep on the floor.

The film’s lack of a budget forced Anders, Voss, and Lent to shoot entirely on location; this enhanced the work, as far as the filmmakers were concerned, since they sought a naturalistic style and look for the feature. Lent���s Echo Park apartment doubled as Jeff’s home, while Anders and Voss’s trailer in Ensenada served as his Mexican hideout. The storied punk hangout the Hong Kong Café (whose neon sign can be seen fleetingly in Chinatown) was utilized, as were the East Side rehearsal studio Hully Gully, where virtually every local band of note honed their chops, and the music shop Rockaway Records (one of the few punk stores of the day still around).

Befitting the work of film students on their maiden directorial voyage, Border Radio evinces the heavy influence of both the French new wave of the sixties and the New German Cinema of the seventies. The confident use of improvisation—the cast is credited with “additional dialogue and scenario”—recalls such early nouvelle vague works as Breathless. The ongoing “interview” device immediately recalls Jean-Pierre Léaud’s face-to-face with “Miss 19” in Jean-Luc Godard’s Masculin féminin, while Shearer’s shambling comedic outbursts are reminiscent of the sudden madcap eruptions in François Truffaut’s early films. The work of the Germans is felt most in the great pictorial beauty of Lent’s black-and-white compositions; certain striking moments—a languid, 360-degree pan around Ensenada’s bay; an overhead shot of Chris’s foreign roadster wheeling in circles in a cul-de-sac—summon memories of Wenders’s and Werner Herzog’s most indelible images. (Lent would go on to work as a cinematographer on nearly thirty pictures.)

Though the styles and effects of these predecessors are on constant display, Border Radio moves beyond simple imitation, thanks to a sensibility that is uniquely of its time, spawned directly from the scene it depicts so faithfully. Though putatively a “music film,” very little music is actually on view in the picture; mere snatches of two songs are actually performed on-screen. The truest reflection of the period’s punk ethos can be found in the restlessness, anger, self-deception, and anomie of its Reagan-era protagonists.

In Border Radio, one can see what punk rock looked like, all the way to the margins of the frame: in the flyers for L.A. bands like the Alley Cats, the Gears, and the Weirdos taped in a club hallway, in the poster for Andy Warhol’s Frankenstein and the calendars of L.A. repertory movie houses tacked on apartment walls, in the thrift-store togs and rock-band T-shirts (street clothes, really) worn by the players. But, more importantly, the shifting tragicomic tone of the film, the energy and attitude of its musician performers, and the uneasy rhythms of its characters’ lives present a real sense of the reality of L.A. punkdom in the day.

Put into limited theatrical release in 1987, by the company that distributed the popular surf movie Endless Summer—a film that offers a picture of a very different L.A.—Border Radio was not widely seen and later received only an elusive videocassette release through Pacific Arts (the home-video firm founded, ironically enough, by Michael Nesmith of the prefab sixties rock group the Monkees). With this Criterion Collection edition, the film can finally be seen as the overlooked landmark that it is: possibly the only dramatic film to capture the pulse of L.A. punk—not as it played, but as it felt.

(Thanks to Allison Anders for her invaluable contributions.)

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Famous Muses & Groupies in Rock Music Pt. 27

MUSE: Molly Ringwald (full name Molly Kathleen Ringwald)

Molly was born on February 18th, 1968 in Roseville, CA as one of three daughters to Bob and Adele Ringwald. Molly started her performing career at age 5 with a local Sacramento theatre production of ‘Alice Through the Looking Glass,’ and that same year she recorded a jazz-pop album called ‘I Wanna be Loved by You.’ By the time she was in middle school, she’d already completed an LA production of ‘Annie’ in 1978 and right afterwards landed her first screen role as one of the original students on “The Facts of Life” (1979-80). Molly was let go from the sitcom after only the first season, but then got to play John Cassavetes’ and Gena Rowlands’ daughter in Paul Mazursky’s all-star ensemble Tempest (1982). It was this film where comedy writer-director John Hughes first saw Molly and was so impressed, he wrote a script just for her. The movie turned out to be the iconic teen movie Sixteen Candles (1984), and made her a star overnight. Molly’s ginger-haired presence resonated with every-day, average teen girls in a more relatable way than young movie stars had been in the past. She continued to be John’s leading lady and inspiration with his hits The Breakfast Club (1985) and Pretty in Pink (1986).

But soon after the success of Pretty in Pink, Molly turned down the female lead in the film’s ‘spiritual sequel’ Some Kind of Wonderful (1987), afraid of being typecast. John took the decision a little too sensitively and didn’t speak to her again for almost a decade. Besides their films together, Molly also starred in the dramas Surviving (1985) and Fresh Horses (1988), and the romcoms The Pick-up Artist (1987) and For Keeps (1988) throughout the 1980s. She was also in the cult sci-fi flick Spacehunter (1983) and Jean-Luc Godard’s bizarre King Lear (1987) feature. Molly’s popularity teetered by 1990 because she kept turning down movies that happened to turn into classics, like Blue Velvet (1986) and Pretty Woman (1990) for flops like Betsy’s Wedding (1990). Despite the bombs, Molly continued to steadily act, like with Billy Bob Thornton’s original short film Some Folks Call It a Sling Blade (1994); the mini-series of Stephen King’s “The Stand” (1994); tongue-in-cheek appearances in Teaching Mrs. Tingle (1999) and Not Another Teen Movie (2001); and regular roles on “The Secret Life of the American Teenager” (2008-13) and “Riverdale” (2017- ). She’s also an accomplished writer with two published books—Getting the Pretty Back (2010) and When It Happens to You (2012)—and a column in The Guardian newspaper since 2014.

As Molly’s stardom was blowing up in her youth, she not only had a glam public image and resume, but also dated her fair share of interesting dudes. Her first famous boyfriend was fellow Hughes collaborator, Anthony Michael Hall in between filming Sixteen Candles and The Breakfast Club. The pair only lasted about 4 months according to Michael, though they ended the fling casually and just went back to being friends. Less than a year later, Molly met Frank Zappa’s own musically talented son, Dweezil. The actress and guitarist were introduced through Dweezil’s older sister Moon Unit, and had a high-profile relationship from 1985-86. Molly was quoted in a 1986 People Magazine article calling Dweezil “totally gorgeous.” The couple occasionally jammed together musically, and Dweezil appeared in one of the club scenes of Pretty in Pink. In a 2014 interview with PennLive, Dweezil revealed that he’s never actually liked the movie that much. Near the end of their love affair, Dweezil & Molly appeared on the Spring 1986 cover and were profiled in In Fashion Magazine.

From 1987-88, Molly went from rock royalty, to rap-rock rebellion with Beastie Boy Ad-rock (Adam Horovitz). They met during production of The Pick-up Artist, where the BB song ‘She’s Crafty’ was on the soundtrack. Molly claims she was the one who asked Adam out because he was “so cute.” She traveled on her first rock tour with the trio, but only lasted half a month because she found the after-partying exhausting. Adam then allegedly spent the rest of the tour calling her every single day. Even though her artistic partnership with John Hughes ended awkwardly, Molly still attended the premiere of Some Kind of Wonderful, with Adam as her date. Reporter Jace Daniel remembers the couple getting into an argument after the screening, with Molly continually brushing off Adam—who was acting boorish. The pair also appeared at the Oscars a month later. In a 1992 Spin cover story on Adam, he admitted that he was already attracted to subsequent girlfriend Ione Skye while he was still with Molly.

Molly’s first marriage was to French writer Valéry Lameignère from 1999 to 2002. Since 2007, she’s been married to book writer and editor Panio Gianopoulos, with whom she has two daughters and a son.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Read it and then read it again.

https://www.killyourdarlings.com.au/article/the-arts-crisis-and-the-colonial-cringe/

The Arts Crisis and the Colonial Cringe

The arts industry in Australia is at a precipice—decimated by the pandemic and systematically starved of funding. Instead of advancing an economic and nationalist argument for the value of the arts, we need to confront Australia’s cultural estrangement and reorient the sector towards social justice.

By

Lauren Carroll Harris

15th Oct, 2020

‘Art is a really bad word here.’

——John Cassavetes

‘If you want to destroy something, a standard method is first to defund it.’

——Noam Chomsky

*

For months now, art has lived almost entirely on the internet. Museums battened down. Ticketing revenue from cancelled cultural events vanished. Major cultural institutions made frictionless, robotic virtual gallery tours their go-to method of adaptation. And as unemployment in the arts soars, the Federal Government’s late stimulus package—tiny in comparison to the size of the industry, precluding basics like hardship payments, still unspent—expressed contempt for practicing artists and the sector’s grassroots. The recent federal budget has reinforced the Government’s tactic: turning away from whichever sector it deems to be an ideological opponent with fatal indifference.

One of the earliest cultural responses in this country to the COVID-19 catastrophe was to bunker down and look inward: with the suspension of air travel, touring and international acts came a call for insularism, to enlarge ‘the breadth, calibre and impact of Australian stories that our festivals could help commission, nurture and unleash every year.’ A column in the Guardian quoted festival directors putting together programs that discuss ‘what it means to be Australian’ and celebrate ‘our place and our home.’

It struck me as puzzling. A festival can program an author or activist to speak via Zoom from anywhere in the world, or commission newly produced podcasts and radio plays by authors whose book tours have been cancelled. Video artists can collaborate remotely with their editors and sound designers to cut together new projects. Writers can work on scripts across borders and hold Skype meetings with international mentors. You can activate your VPN and click onto a trove of world cinema. Digital curators can open up access to new art to anyone, anywhere in the world, 24/7. And yet amid this internationalisation of culture, in Australia, the same tired, milquetoast cultural narratives about art’s service to national identity were being rehearsed.

I know what you’re about to say: I’m indulging in the cultural cringe. But I’m beginning to think many of us have lost sight of what that term really means. And that may be the whole problem.

*

A.A. Phillips’ seminal essay on the cultural cringe first appeared in Meanjin in 1950, describing an internalised inferiority complex, mainly regarding literature; Australian writing at the time was not thought worthy of undergraduate study. ‘Australia is an English colony,’ wrote Phillips, at a time when Australians were still British subjects by definition, and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people had not yet won suffrage. ‘Its cultural pattern is based on that fact of history or, more precisely, on that pair of facts… But the fact of our colonialism has a pervasive psychological influence, setting up a relationship as intimate and uneasy as that between an adolescent and his parent.’

The cringe’s historical origins lie in the material reality of colonialism, producing what literary academic Emmett Stinson has since called a wider set of anxieties about Australian culture in relation to the world around it. Colonists denied and evicted the cultures of this continent’s custodians and supplanted it with their own. That process cemented a displacement of culture at Australia’s heart—art lost its origin—as well as a tendency to look abroad (at first to Britain, the culturally dominant hegemony, then to the US) for cultural confirmation.

When we talk about the cultural cringe, we’re really talking about the colonial cringe.

What we are seeing this year is the arts sector grapple, or rather, refuse to grapple, with its decline and gradual rejection as a federally funded public project.

Today, though, the term stands in for a form of reflexive reverse snobbery—a lazy satisfaction with the status quo and whatever is made here. Contemporary usage of the term is cut adrift from that understanding of colonial culture, which was key to Phillips’ argument: that Australia’s subservience to overseas cultural values, specifically, British cultural values, came from it’s ‘umbilical connection’ to the literature, art and ideas of its colonial parent. Consider that the Art Gallery of NSW didn’t consider Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art worthy of collection until the 1950s; that Queen Elizabeth opened the National Gallery of Australia as late as 1982.

Phillips confessed that at times ‘a raucous nationalism’ had led to excessive ‘over-praise’ for Australian works. Indeed, the popular interpretation of the term now is used to shut down discussion, to automatically praise local culture with an uncritical eye, such that it is almost impossible to advance a critique of Australian culture without being dismissed as an unthinking imbiber of the cultural cringe.

That’s the paradox—that the term cultural cringe is now called upon regularly with the same assumed anti-intellectualism that Phillips wished to challenge. I still believe that the best, or rather, only way, to grow the standing of the arts here is to engage with it critically and rigorously—to discard the implicit idea that anything Australia produces is above critical engagement simply because it is Australian. The question then becomes how to investigate the history of art and culture when, historically, there have been few institutional channels here to do so?

What we are seeing this year is the arts sector grapple, or rather, refuse to grapple, with its decline and gradual rejection as a federally funded public project. As this happens, it should reckon with where it first drew its power and what it replaced—what A.A. Phillips called the ‘colonial dilemma’. This cultural estrangement will continue, until the problem of colonialism is materially addressed. The centre of this society is missing a knowledge that should have been omnipresent. How will we choose to live, with such emptiness?

*

These things set in motion 250 years ago are still bearing out. The cultural subservience and intellectual timidity that Phillips described was baked into the structure of Australian life, from everything to the economy to citizenship. Australia never has kicked out the Brits. Still, it is the only colonial country that has not engaged in a process of treaty, truth-telling and justice on a national level (Victoria’s formal movement toward this is a necessary, heartening step).

That means that history isn’t finished with us. The defunding of the arts is of course nowhere near equivalent to colonialism and genocide, but they’re part of the same project—bending this country’s narratives and history backwards in service of lies to substantiate settler-colonial Australia’s existence and the sideswept racial guilt that haunts every aspect of life here.

Now, the art world is also facing the great failure of neoliberalism—of the logical endpoint of defunding, privatising, removing state influence and casting off formerly federal projects to states and councils. The parts of the art world founded on neoliberal economics—Carriageworks, namely, a private cultural enterprise that stayed afloat by way of venue hire to commercial activities—haven’t avoided catastrophe, rather, they’ve faced catastrophe first.

Rather, the art sector’s response to the twin crises of whiteness and defunding comes from its dedication to a tradition that promotes individual achievement rather than collectivism like political action, nonviolent organising, picket lines, marches. The impact of COVID-19 hasn’t been helped by the fact that, unlike the US arts sector, Australian museums, galleries, cinemas, theatres and festivals—which usually conceive of themselves as physical spaces, events, collections and so on—have never developed much in the way of online infrastructure and expertise with which to commission and exhibit new digital programs.

Does the Australian arts sector have the strategy and power to get what it wants? Does the electorate care enough to act, and vote, and make the arts’ defunding politically unacceptable?

Does the Australian arts sector have the strategy and power to get what it wants? Does the electorate have faith in contemporary art and culture? If so, do they care enough to act, and vote, and make the arts’ defunding politically unacceptable? Many artists and advocates have made noble, decades-long attempts to patiently explain what art contributes to a social democracy. For those of us working in the arts, its necessity is almost too ubiquitous to grasp and too transparent to prove. Rehearsing the same arguments on the back foot is pointless—the art’s displaced basis here is material, in the foundation of how this society is organised to evict one set of cultures and overlay new ones.

At present, there is enough evidence to suggest that the attacks against the arts have already been successful. It has been a political project. Even before the coronavirus forced the cancellation of cultural events, the Australian public’s art attendance only appears high because it tends to be measured in yearly brackets. Diversity Arts recorded that 71% of Australians attended art events in the year preceding the study, which institutes a low benchmark for arts participation (there’s a dearth of data on regular—say, weekly—arts attendance). In more recent research by Australia Council for the Arts, one in four people said that there were no arts events near where they live. They live in an arts desert. Cost is cited as another thing preventing more people from attending art more regularly. This data is hugely substantial. It spells out a failure in arts policy to provide access to art to everyone regardless of where they are and how much they earn. If the arts sector is to win back its funding, it needs to rapidly expand its audience within the general public. Artists are good at envisaging an audience; now this audience needs to be thought of as the sector’s allies, agents and actors for change.

Art has, since 1788, assumed a minority status. Form-breaking, adventurous modes of artmaking like moving image, net art, hybrid and experimental arts and, until recently, digital forms of exhibition, have very little institutional support here. Depletion of funding leads to depletion of ambition, experimentation and innovation. Meanwhile, media outlets often run more opinion pieces bemoaning the arts crisis than they do critically reviewing new Australian work. The arts bloodbath has outrun the arts’ output—the crisis is the story. Artists are now starved both of their bread-and-butter and a wide critical responsiveness.

The arts sector has refrained for calling for restoration of public cultural aid to, say, 1990s levels. Its main tactics to appeal for relevance from middle Australia—comparing Australians’ support of the arts to its love of sport, arguing the sector’s value in neoliberal dollar terms and employment numbers—have failed to stem the blood loss. The remaining line of argument is that the arts are essential to who we are as a country. Holding up a mirror to our life as a nation. Examining who we are, our national identity. The narrators of our nation. What it means to be Australian. These words are generally uttered with goodwill, but a terrible conservatism haunts them. It must be said: this vision of an absurd, unhealthy, nationalistic identity has backfired. The history of the cultural cringe suggests that Australia’s national existence has been predicated on the eradication of particular forms of cultural life rather than its encouragement, and its importation from greater global powers. Being Australian is absolutely congruent with degrading, ignoring and deleting culture. Art and the people who make it barely figure in the imagined community of Australia.

I’m wary and worried about the way that many of us have internalised funding agency-speak of ‘celebrating Australian stories.’ I’m more interested in art that is a window to other places and ways of thinking.

Over the course of my time contributing to the arts and media, I’ve come to reassess the ways in which I naively contributed to what I now see as a kind of liberal, culturally nationalist conversation that says that the work of the arts should necessarily advance a national interest or even, in academic Julian Meyrick’s words, to persuade the nation to examine its own soul. Some artists may think of their work in that way, but art also precedes nations and borders and federations. I’m wary and worried about the way that many of us have internalised funding agency-speak of ‘celebrating Australian stories.’ I’m more interested in art that is a window to other places and ways of thinking, and culture as a project of enlargement, future possibilities and internationalism.

The arts sector’s response has also been separate from a concept of social justice beyond its spaces. It has no memory of collective power. From the top down, it values career development over social justice for its practitioners. The forces of economic segregation and sexism, austerity and racism, division and austerity bearing down on the world are the same as those in the arts. Curator Liz McNiven makes the point that the growth of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander filmmaking only took off after decades of pressured progress in civil rights, social participation and legal representation—the self-representation in Bla(c)k screen art we see today is not just a function of creative and industry forces. Lack of structural opportunity means that those with financial mobility, inherited wealth, parental generosity or spousal support—or those who can bear the poverty and hardship—can make a living in the arts. There’s no possible diverse, thriving, funded art sector without a materially just society that acts on issues like decommodifying housing and issuing a universal basic income. Diversity in the arts isn’t purely a curatorial project, it’s also a social justice project. It means the arts, and society beyond it, confronting its relationship to First Nations dispossession and the potential of sovereignty.

The most dangerous discourses are often the benevolent liberal ones that hide deeper systemic prejudices and allow oppressive structures to continue invisibly. Rather than automatically confirming and celebrating who we are as Australians, the arts need to critically engage with this continent’s history. It could also reject the idea that art here must address the concept of Australian nationhood, and work instead to think about regional, local, marginalised and community identities and how those identities connect to the rest of the world. It could even take apart the very concept of Australia and think beyond Anglo-founded empires. To this end, I’ve noticed that many of the most audacious young artists do not frame their work around a national vision, and often they’re not addressing Australia at all, but link their own very specific experiences of living across cultures to broader global narratives of diaspora, lineage and family displaced by movement. I’m inclined toward the view that the most interesting art is taking place outside a national lens.

Another glittering instance of this internationalism is Brook Andrews’ Sydney Biennale, NIRIN, a program that gathers the work of Indigenous and First Nations artists from around the world. Though many in the art world have reflexively read NIRIN as a decolonising project, Andrews’ curatorial statement makes no mention of Australia. Rather than nationhood, the NIRIN website speaks primarily about sovereignty; rather than trying to insert Indigenous voices into imposed colonial narratives, the works simply stand for themselves—a quietly radical shift in the discourse, moving away from national boundaries and borders.

The small screen sometimes offers flashes of insight as to what art can look like when it doesn’t automatically address Australian identity. Made in Arnhem Land, ABC TV’s short creative documentary series Black As is fascinating in that it does not really take place in the imagined community of ‘Australia’. Its situation is the Ramingining community, its language is Djambarrpuyngu and its collaborators—Jerome Lilypiyana, Chiko Wanybarrnga, Dino Wanybarrngu, Joseph Smith—are constantly honouring law and land in small ways along their epic, mundane, hilarious journeys across country.

There’s no possible diverse, thriving, funded art sector without a materially just society. Diversity in the arts isn’t purely a curatorial project, it’s also a social justice project.

As a nation where language and images are used to obfuscate and mislead, Australia has designated its own sacred sites since invasion: statues of Winston Churchill, King George V and Queen Elizabeth in capital cities, monuments to Captain Cook along the coast where he put English names to places already named. This is where art and politics bisect right now. Statues and monuments show the myths of the nation—what is deemed worthy of being remembered, who is seen as central to the stories a country tells about itself. Tearing down statues that unthinkingly celebrate colonialism, and instead, placing them in museums, whose purpose is to interrogate and contextualise the past, designed as a gesture of cultural compensation.

And yet 2020 is also showing us the limits of art and the necessity of systemic change. Change requires policies and legalities like defunding the police, abolishing jails, establishing free childcare so that domestic labour is socialised rather than delegated to women. What can culture do? Some of the work of truth-telling, some of the work of renovating our myths and heroes. There is not much in Australian history’s cultural narrative that would suggest to you that art predates borders and nations, and that people of all genders, ethnicities, sexualities and worldviews make art. But through engaging with the social world, art can guide us through its attendant dramas of colonialism, class, race, gender, sexuality, empire and capitalism. What is art if not a search for a collective memory? As curator and artist Djon Mundine said recently, art can help this place make ‘the conceptual leap to be honest about the past.’ That means the crimes committed against First Nations people and ecologies so that an Australian nation might exist.

I’m not here to depress you or to kick a sector while it’s down. How we change the ending of the arts’ sorry downward trajectory is still to be decided. I believe the sector’s future is tied up with art as a form of community mobilisation and political action as part of a shift in the national consciousness. It’s tied up with how social change happens, and how we change the ending of this country’s sordid relationship with colonialism. Formal recognition of genocide, compensation, treaties, the teaching of Indigenous history, culture and languages in schools, and the empowerment of First Nations communities to govern their own affairs are part of this historical and cultural reckoning. There could have been a hundred Emily Kame Kngwarreyes, a hundred Nora Wompis. There still could be a hundred Tracey Moffats.

I’m only pessimistic as long as the public conversation carries on in the current mood of bewilderment and paralysis. Through history, the most unthinkable crises have led to serious debates and movements in which the future is reassembled and real progress is made. If you’re tired, act. It might be the only way to pull yourself—and the culture—out of inertia. I used to traffic in the culturally nationalist, local boosterist reasons for funding the arts. Now, only one reason remains in my mind: I want to live in a smart country.

End

0 notes

Photo

Lana Del Rey: Wild At Heart

‘Is this the mysterious Lana Del Rey?’ — set to release her era-defining fifth LP, pop's dream-queen shoots the LA breeze with grunge hellraiser Courtney Love.

Editor's Note: This interview has been condensed from the print edition.

Courtney Love’s gravelly voice is unmistakable on the line next to Lana Del Rey’s syrupy sing-song: “Is this the one and only Courtney Love?”

It’s been a while since any of us has heard from Del Rey. She’s calling Love from her home in California a few weeks after releasing “Love”, the booming, lounge-y first single off her upcoming fifth studio album, Lust for Life. Although Del Rey’s last record, Honeymoon, was released only a year and a half ago, that particular span has felt like forever. An anti-anthem of sorts, “Love” takes into account turbulent times, offering commiseration as opposed to call-to-action. Lines like “the world is yours and you can’t refuse it” slip under a ringing chorus that proclaims, “You get ready, you get all dressed up to go nowhere in particular.” The video rockets a group of teenagers, current-day devices in hand, to a vintage-rendered outer space.

It’s a message that could easily be mistaken for nihilism. A month earlier, though, Del Rey pre-empted criticism by Instagramming the Nina Simone quote, “An artist’s duty, as far as I’m concerned, is to reflect the times.”

Which is perhaps what Del Rey does best. Lust for Life could be called the next chapter in a long-running investigation into era-non-specific youth qualifiers that started with the self-directed video for her breakout single, “Video Games”. That song perfectly crystallised a mood and a moment, splicing an at-home aesthetic heretofore only found in webcam vlogs with imagery of a 1950s red carpet, an iPod billboard, and Paz de la Huerta falling in front of paparazzi. While Del Rey often insists that she’s lost in reverie, obsessed by the past, her music is a poignant reflection of a generation that continues to resist expectations. It’s a study, too, of femininity in general. For isn’t womanhood itself, she appears to ask, steeped in anachronism?

Both Lana Del Rey and Courtney Love write about irresistible institutions – Hollywood, mainstream acceptance and powerful men. The heartbreaking twist of each narrative is that the singers will always be outside the circles they describe desiring. While Love deftly played the unfiltered outsider as frontwoman with Hole through the 90s, in the age of infinite footnotes, Del Rey has taken up the role of oblivious misfit, more prone to a pout than a scream.

Two decades apart in age, similarities between the two women (who played eight shows together in 2015 for Del Rey’s Endless Summer tour) are irrefutable. What if Love had come of age when Del Rey did, when every professional move she made was documented on Wikipedia within moments? Or if Del Rey grew up in a time when she would have to petition for music reviews, even as the wife of a huge rock star? Would one more closely resemble the other? Either way, each has become a Cassavetes-esque tragic figure in her performed world, toeing the line between outlying cult hero and revered pop star.

“People ask me about musical similarities between our stuff,” Del Rey says to Love, who is calling from a movie set in Vancouver. “I just know it’s the kind of music I listen to all the time: when I’m driving, or when I’m alone, or when I’m with friends.”

You can buy a copy of Dazed’s latest issue here. Taken from the spring/summer issue.

Lana Del Rey: So, we could just talk about whatever... Like those burning palm trees that you had in the ‘Malibu’ video. I didn’t think they were real!

Courtney Love: Back when rock’n’roll had budget, you mean? Oh my God, Lana, setting palm trees on fire was so fun. You thought they were CGI?

LDR: Yeah.

CL: God, you’re so young. I burned down palm trees. In my day, darling, you used to have to walk to school in the snow. So, since I toured with you, I got kind of obsessed and went down this Lana rabbit hole and became – not like I’m wearing a flower crown, Lana, don’t get ideas – but I absolutely love it. I love it as much as I love PJ Harvey.

LDR: That’s amazing because, maybe it’s slightly well documented, but I love everything you do, everything you have done – I couldn’t believe that you came on the tour with me.

CL: I read that you spend a lot of time mastering and mixing. Is that true on this new record?

LDR: Oh my God, yeah, it’s killing me. It’s because I spend so much time with the engineers working on the reverb. Because I actually don’t love a glossy production. If I want a bit of that retro feel, like that spring reverb or that Elvis slap, sometimes if you send it to an outside mixer they might try and dry things up a bit and push them really hard on top of the mix so it sounds really pop. And Born to Die did have a slickness to it, but, in general, I have an aversion to things that sound glossy all over – you have to pick and choose. And some people say, ‘It’s not radio-ready if it isn’t super-shiny from top to bottom.’ But you know this. Whoever mixed your stuff is a genius. Who did it?

CL: Chris Lord-Alge and Tom Lord-Alge. Kurt was really big on mastering. He sat in every mastering session like a fiend. I never was big on mastering because it’s such a pain in the butt.

LDR: It is a pain in the ass.

CL: I think my very, very favourite song of yours – you’re not gonna like this because it’s early – is ‘Blue Jeans’. I mean, ‘You’re so fresh to death and sick as ca-cancer’? Who does that?

LDR: I have to say, that track has this guy (Del Rey collaborator) Emile Haynie all over it. I remember ‘Blue Jeans’ was more of a Chris Isaak ballad and then I went in with him and it came out sounding the way it does now. I was like, ‘That’s the power of additional production.’ The song was on the radio in the UK, on Radio 1, and I remember thinking, ‘Fuck, that started off as a classical composition riff that I got from my composer friend, Dan Heath.’ It was, like, six chords that I started singing on.

CL: You have that lyric (on the song), ‘You were sorta punk rock, I grew up on hip hop.’ Did you really grow up on hip hop?

LDR: I didn’t find any good music until I was right out of high school, and I think that was just because, coming from the north country, we got country, we got NPR, and we got MTV. So Eminem was my version of hip-hop until I was 18. Then mayb I found A Tribe Called Quest.

CL: Have you met Marshall Mathers?

LDR: No. Sometimes he namechecks me in his songs. I called the head of my label (Interscope CEO) John Janick and I was like 'OK in this last song (Big Sean's "No Favors") when Eminem says 'I'm about to run over a chick, Del Rey CD in’. Did he mean he wanted to run me over or was he listening to me while he ran someone over?'. And John was like, 'No, no he was listening to you while he ran someone over' and I was 'Ok, cool.'

CL: You got namechecked by Eminem? oh my god that is a jewel in the crown.

LDR: Just a little ruby.

CL: Yeah, it's not really a diamond, but it's a ruby.

LDR: Not like touring with Courtney Love. That's like an Elizabeth Taylor diamond.

CL: You know, I met Elizabeth Taylor. I was with Carrie Fisher at (Taylor’s) Easter party and she was taking six hours to come downstairs.

LDR: I love it.

CL: I looked at Carrie and I said, ‘This is not worth it,’ and Carrie said, ‘Oh, yes it is.’ So we snuck upstairs and, Lana, when you go past the Warhol of Elizabeth Taylor as you’re sneaking up the stairs and it says ‘001’, you start getting goosebumps. And then you see her room and it’s all lavender, like her eyes. And she’s in the bathroom getting her hair done by this guy named José Eber who wears a cowboy hat and has long hair, and I’m like, ‘What am I doing here? I’m not Hollywood royalty.’ And the first words out of her mouth are, like, ‘Fuck you, Carrie, how ya doin’?’ She was so salty but such a goddess at the same time.

LDR: She was so salty. The fact that she married Richard Burton twice – and all the stories you hear about those famous, crazy, public brawls – she was just up for it. Up for the trouble.

CL: So back to you. What I hear in your music is that you’ve created a world, you’ve created a persona, and you’ve created this kind of enigma that I never created but if I could go back I would create.

LDR: Are you even being serious right now? I don’t even know if your legacy could get any bigger. You’re one of the only people I know whose legacy precedes them. Just the name ‘Courtney Love’ is… You’re big, honey. You’re Hollywood. (laughs).

CL: You know what, darling? I started real early. I started stalking Andy Warhol before I could even think about it. And you kind of did the same, from my understanding. That ‘I want to make it’ thing. And there’s nothing wrong with that.

LDR: No, there’s not. There’s nothing wrong with it when you do the rest of it for the right reasons. If music is really in your blood and you don’t want to do anything else and you don’t really care about the money until later. It’s also about the vibe, not to be cliched. And the people. I think we had that in common. It was about wanting to go to shows, wanting to have your own show – living, breathing, eating, all of it.

CL: Can I ask you about your time in New Jersey? Was that a soul-searching time?

LDR: Oh, I don’t even know if I should have said to anyone that I was living in that trailer in New Jersey but, stupidly, I did this interview from the trailer, in 2008.

CL: I saw it!

LDR: It’s cringey, it’s cringey. (laughs)

CL: You look so cute, though.

LDR: I thought I was rockabilly. I was platinum. I thought I had made it in my own way.

CL: I understand completely.

LDR: The one thing I wish I’d done was go to LA instead of New York. I had been playing around for maybe four years, just open mics, and I got a contract with this indie label called 5 Points Records in 2007. They gave me $10,000 and I found this trailer in New Jersey, across the Hudson - Bergen Light Rail. So, I moved there, I finished school and I made that record (Lana Del Ray a.k.a. Lizzy Grant), which was shelved for two and a half years, and then came out for, like, three months. But I was proud of myself. I felt like I had arrived, in my own way. I had my own thought and it was kind of kitschy and I knew it was going to sort of influence what I was doing next. It was definitely a phase. (laughs)

CL: But you have records about being a ‘Brooklyn Baby’. You can write about New York adeptly and I cannot. I tried to write a song about a tragic girl in New York, going down Bleecker Street – this girl couldn’t afford Bleecker Street, so the song made no sense, right? (laughs) I did my time there, but it chased me away. I couldn’t do it because I wouldn’t go solo. I had to have a band.

LDR: I wanted a band so badly. I feel like I wouldn’t have had some of the stage fright I had when I started playing bigger shows if (I had) a real group and we were in it together. I really wanted that camaraderie. I actually didn’t even find that until a couple of years ago, I would say. I’ve been with my band for six years and they’re great, but I wished I had people – I fantasised about Laurel Canyon.

CL: I wanted the camaraderie. The alternative bands in my neighbourhood were the (Red Hot Chili) Peppers and Jane’s (Addiction). I knew Perry (Farrell, Jane’s Addiction frontman) and I went to high school for, like, ten seconds with two Peppers and a guy named Romeo Blue who became Lenny Kravitz. I remember being an extra in a Ramones video and he stopped by, when he was dating Lisa Bonet from The Cosby Show and it was a big deal.

LDR: See? You didn’t really see that in New York. When I got there, The Strokes had had a moment, but that was kind of it. LA has always been the epicentre of music, I feel.

CL: LA is easier. People have garages. And then as you go up the coast, in Washington and Oregon people have bigger houses and bigger garages, and people have parents. I didn’t have parents, and you – well, you had parents, but you were on your own.

LDR: Yeah. You know that song of yours (‘Awful’) that says, ‘(Just shut up,) you’re only 16’? I think there are different types of people. There are people who heard, ‘What do you know? You’re just a kid,’ and then there are people who got a lot of support (from the line), like, ‘Go for it, go for your dreams.’ (laughs) And I think when you don’t have that, you get kind of stuck at a certain age. Randomly, in the last few years, I feel like I’ve grown up. Maybe I’ve just had time to think about everything, process everything. I’ve gotten to move on and think about how it feels now, singing songs I wrote ten years ago. It does feel different. I was almost reliving those feelings on stage until recently. It’s weird listening back to my stuff. Today, I was watching some of your old videos and this footage of you playing a big festival. The crowd was just girls – just young girls for rows and rows. I was reminded of how vast that influence was on teenagers. And – going back to enigma and fame and legacy – you know, those girls who have grown up and girls who are 16 now, they relate to you in the exact same way as they did right when you started. And that’s the power of your craft. You’re one of my favourite writers.

CL: You’re one of mine, so, checkmate. (laughs)

LDR: What you did was the epitome of cool. And there’s a lot of different music going on, but adolescents still know when something comes authentically from somebody’s heart. It might not be the song that sells the most, but when people hear it, they know it. Are you a John Lennon fan?

CL: When I hear ‘Working Class Hero’, it’s a song I wish to God I could write. I wouldn’t ever cover it. I mean, Marianne Faithfull covered it beautifully, but I would never cover it because I think Marianne did a great job and that’s all that needs to be said.

LDR: I felt that way when I covered ‘Chelsea Hotel (#2)’, the Leonard Cohen song, but when I was doing more acoustic shows, I couldn’t not do it.

CL: I don’t have your range. I’ve tried to sing along to ‘Brooklyn Baby’ and ‘Dark Paradise’ and this new one, ‘Love’. You go high, baby.

LDR: I’ve got some good low ones for you. You know what would be good, is that song, ‘Ride’. I don’t sing it in its right octave during the shows because it’s too low for me. But I’ve been thinking about doing something with you for a little while now. Then after we did the Endless Summer tour, we were thinking we should at least write, or we should just do whatever and maybe you could come down to the studio and just see what came out.

CL: When we were on tour, our pre-show chats were very productive for me.

LDR: Me too. That was a real moment of me counting my blessings. I just wanted to stay in every single moment and remember all of it, because it was so amazing.

CL: Likewise. It was really fun coming into your room. My favourite part of the tour was in Portland, getting you vinyl that I felt you needed. (laughs)

LDR: When you left the room, I was just running my hand over all the vinyl like little gems, like, ‘I can’t believe I have these (records) that Courtney gave to me, it’s so fucking amazing.’ And we were in Portland, too. It felt surreal.

CL: Yeah, I don’t like going there much but I went there with you. We have this in common, too: we both ran away to Britain. If I could live anywhere in the world, I’d live in London.

LDR: If I could live anywhere in the world other than LA, I’d live in London. In the back of my mind, I always feel like I could maybe end up there.

CL: I know I’m going to end up there. I know what neighbourhood I’m going to end up in, and I know that I want to be on the Thames. I subscribe to this magazine called Country Life which is just real-estate porn and fox hunting. It’s amazing. OK, so, if you weren’t doing you, what would you do?

LDR: Do you have a really clear answer for this, for yourself?

CL: Yeah, I would work with teenage girls. Girls that are in halfway houses.

LDR: That’s got you all over it. I’m selfish. I would do something that would put me by the beach. I would be, like, a bad lifeguard. (laughs) I’d come help you on the weekends, though.

CL: Do you like being in Malibu better than being in town?

LDR: I like the idea of it. People don’t always go out to visit you in Malibu. So there’s a lot of alone-time, which is kind of like, hmm. I’m not in (indie-rock enclave) Silver Lake but I love all the stuff that’s going on around there. I guess I’d have to say (I prefer) town, but I’ve got my half-time Malibu fantasy.

CL: The only bad thing that can happen in Malibu really is getting on Etsy and overspending.

LDR: Oh my God, woman... (laughs) Tell me about it. Late-night sleepless Etsy binges.

CL: Regretsy binges. OK, so, lyrically, you have some tropes and one of them is the colour red. Red dresses, scarlet, red nail polish... I kind of want to steal that.

LDR: You need to take over that, because I think I’ve got to relinquish the red.

CL: Well, I overuse the word ‘whore’.

LDR: You take ‘red’. I’ll trade for ‘whore’. I’m so lucky.

CL: I love this new song (‘Love’).

LDR: Thank you. I love the new song, too. I’m glad it’s the first thing out. It doesn’t sound that retro, but I was listening to a lot of Shangri-Las and wanted to go back to a bigger, more mid-tempo, single-y sound. The last 16 months, things were kind of crazy in the US, and in London when I was there. I was just feeling like I wanted a song that made me feel a little more positive when I sang it. And there’s an album that’s gonna come out in the spring called Lust for Life. I did something I haven’t ever done, which is not that big of a deal, but I have a couple of collabs on this record. Speaking of John Lennon, I have a song with Sean Lennon. Do you know him?

CL: I do, I like him.

LDR: It’s called ‘Tomorrow Never Came’. I don’t know if you’ve ever felt this way, but when I wrote it I felt like it wasn’t really for me. I kept on thinking about who this song was for or who could do it with me, and then I realised that he would be a good person. I didn’t know if I should ask him because I actually have a line in it where I say, ‘I wish we could go back to your country house and put on the radio and listen to our favourite song by Lennon and Yoko.’ I didn’t want him to think I was asking him because I was namechecking them. Actually, I had listened to his records over the years and I did think it was his vibe, so I played it for him and he liked it. He rewrote his verse and had extensive notes, down to the mix. And that was the last thing I did, decision-wise. I haven’t mixed the record, but the fact that ‘Love’ just came out and Sean kind of finished up the record, it felt very meant-to-be. Because that whole concept of peace and love really is in his veins and in his family. Then, I also have Abel (Tesfaye), The Weeknd. He is actually on the title track of the record, ‘Lust for Life’. Maybe that’s kind of weird to have a feature on the title track, but I really love that song and we had said for a while that we were gonna do something; I did stuff on his last two records.

CL: Do you have a singular producer or several producers?

LDR: Rick Nowels. He actually did stuff with Stevie Nicks a while ago. He works really well with women. I did the last few records with him. Even with Ultraviolence which I did with Dan (Auerbach), I did the record first with Rick, and then I went to Nashville and reworked the sound with Dan. So, yeah, Rick Nowels is amazing, and these two engineers – with all the records that I’ve worked on with Rick, they did a lot of the production as well. You would love these two guys. They’re just super-innovative. I wanted a bit of a sci-fi f lair for some of the stuff and they had some really cool production ideas. But yeah, that’s pretty much it. I mean, Max Martin –

CL: Wait, you wrote with Max Martin? You went to the compound?

LDR: Have you been there?

CL: No. I’ve always wanted to work with Max Martin.

LDR: So basically, ‘Lust for Life’ was the first song I wrote for the record, but it was kind of a Rubik’s Cube. I felt like it was a big song but... it wasn’t right. I don’t usually go back and re-edit things that much, because the songs end up sort of being what they are, but this one song I kept going back to. I really liked the title. I liked the verse. John Janick was like, ‘Why don’t we just go over and see what Max Martin thinks?’ So, I flew to Sweden and showed him the song. He said that he felt really strongly that the best part was the verse and that he wanted to hear it more than once, so I should think about making it the chorus. So I went back to Rick Nowels’ place the next day and I was like, ‘Let’s try and make the verse the chorus,’ and we did, and it sounded perfect. That’s when I felt like I really wanted to hear Abel sing the chorus, so he came down and rewrote a little bit of it. But then I was feeling like it was missing a little bit of the Shangri-Las element, so I went back for a fourth time and layered it up with harmonies. Now I’m finally happy with it. (laughs) But we should do something. Like, soon.

CL: I would like that. That would be awesome.

Lust for Life is out this spring.

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

'The Pocket book' Shocker - Ryan Gosling REFUSED To Movie With Rachel McAdams!

http://tinyurl.com/y6rl3hkr