#mannlibrary

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Bird travels

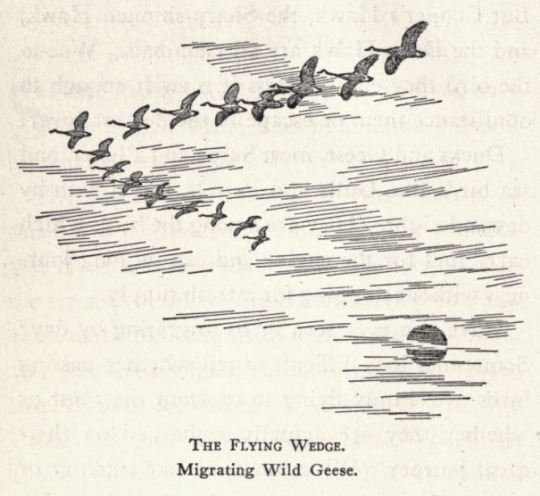

From the great white pelican to the snowy owl — birds spread their wings and flock southward in droves in the late summer and early fall. As the bird lovers among us would likely agree, few natural sights are as breathtaking as a group of cranes flying in a V-formation or a migrating group of snow geese, or even robins, which typically migrate in groups of less than fifty but sometimes gather in groups of hundreds or thousands. For those of us lucky enough to live near migration corridors, the sight of this fall phenomenon can captivate the mind and move the soul.

Over the centuries, many naturalists have attempted to better understand avian migration. One of these was early 20th century American ornithologist and author Frank Chapman. Chapman was a self-taught ornithologist from New Jersey – he is perhaps most well known as an early promoter of the photographic blind in bird photography, and for bringing the science of ornithology to the people through the use of non-specialized language and field guides composed with the bird-loving lay person in mind. As Frank Chapman observed in his lovely 1916 volume, The Travels of Birds, the study of natural history has been replete with thoughtful theorizing about the reasons behind bird migration, some of which have been a little out there (at least in the light of what we do currently know). Writes Chapman “At one time it was thought that some birds flew to the moon. Others, particularly the Swallows and Swifts, were believed to fly into the mud and pass the winter hibernating like frogs; while the European Cuckoo was said, in the fall, to turn into a Hawk.”

Such speculations may sound silly to us today, but the truth is, the facts of bird migration are indeed astonishing — bird populations seemingly disappear en masse overnight, make their way without a map or compass, across hundreds of thousands of miles of land and sea only to reappear every year, hale and hearty after winter’s last thaw. Thanks to insights gathered from careful scientific observation over the years, we now know that our feathered friends are able to navigate using a variety of methods such as a sun compass or olfactory cues, that migration is cued by factors like changes in day length, and that migration is driven to a significant degree by the seasonal availability of nourishment in different regions of the globe.

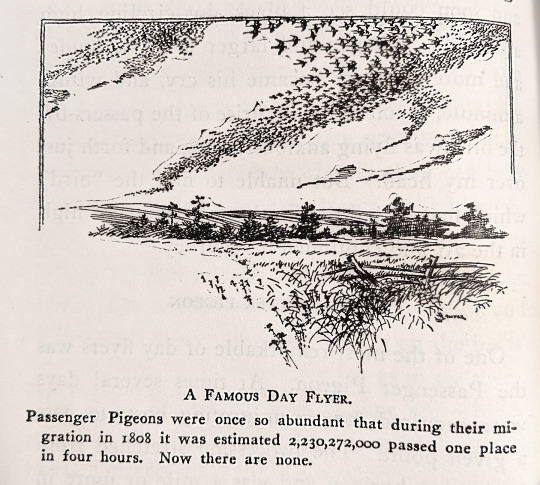

In Travels, Chapman takes a moment to ponder one of history’s most impressive migrants, the North American passenger pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius) whose day-flying migratory group — as observed in the early part of the 1800s at least — could reach flocks that were “a mile or more in width. Often the sun would be obscured by the clouds of flying birds." So great were the numbers of these birds in migration flight that hunters assumed the passenger pigeon would provide them with an inexhaustible supply of income — and used their rifles accordingly. Alas, passenger pigeons were hunted with such reckless abandon, and their deciduous forest habitat was sufficiently degraded during the course of the 19th century, that in less than 100 years, the death of the last known surviving passenger pigeon at the Cincinnati Zoo in 1914 marked their final extinction.

So, while Chapman's lyrical volume about travelling birds does not fail in his goal of evoking in his readers a great (yes we'll call it soaring!) sense of wonder and appreciation about bird migration, it serves as a sobering cautionary tale as well. With brand new research by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology highlighted in Science Magazine just this month suggesting an alarming 30% decline in the general bird population of Canada and the United States since the early 1970s, it's a tale that we would be wise to take seriously to heart.

Sources:

wikipedia

audubon.org

catalog.hathitrust.org

#birds#migration#Ornithology#specialcollections#rarebooks#vaultsofmann#mann library#mannlibrary#passenger pigeon

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Janet Harvey Kelman

Janet Harvey Kelman (1873-1957), Scottish illustrator and author, new on my blog. Kelman illustrated many natural history books for children, including Butterflies and Moths (1910). Thanks to @mannlibrary of Cornell University Library for contributing this book for digitization in @biodivlibrary. Explore more of her butterflies and moths in #BHLib's Flickr album.

#historicalsciart#womeninhistsciart#art#janetharveykelman#cornelluniversitylibrary#biodiversity#bhlib#womeninscience#womeninnaturalhistory#scientificart#femaleartists#scientificillustration#womenshistorymonth#biodiversityheritagelibrary#femaleillustrators#naturalhistory#histsciart#mannlibrary#science

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

mannlibrary: American toadstool Chanterelles, King Boletes, Waxcaps, Cauliflower Corals, and... https://ift.tt/2oCXoen

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Learn more about green screen. Chk link in bio. Reposted from @doinkapps (@get_regrann) - At the MannLibrary they are getting in some #Greenscreen basics with #doink! It was a lot of activity but they squeezed in a few basics. They learned that mistakes will be made, but they also learned how to correct + problem solve. It takes teamwork. #everyonecancreate https://www.instagram.com/p/B7CtPoPhN7O/?igshid=whoi6c619lqf

0 notes

Photo

Happy Big Caturday!

Cougar (Puma concolor) by Louis Agassiz Fuertes for Edward William Nelson, The Larger North American Mammals (1916).

Contributed for digitization by Cornell University Library (@mannlibrary) to the Biodiversity Heritage Library.

#cats#scientificillustration#cougar#puma#bhlib#mountainlion#naturalhistory#openaccess#caturday#librariesofinstagram#sciartfix#biodiversityheritagelibrary#biodiversity#scientificart#bigcats

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Wed 11/28 11-4pm @cornelluniversity @mannlibrary LiXTiK ithaca soap and wendy ives felt art @cufarmersmarket #cornellfashioncollective #mannlibrary #farmersmarket #winterfashion #sustainable #cufarmersmarket #mandible #cornell #lipbalm #presents #gifts (at Manndible Cafe) https://www.instagram.com/p/BqsFNUeA9vU/?utm_source=ig_tumblr_share&igshid=tplxmqvu5apj

#cornellfashioncollective#mannlibrary#farmersmarket#winterfashion#sustainable#cufarmersmarket#mandible#cornell#lipbalm#presents#gifts

0 notes

Text

Celebrating LGBTQ Scientists

June is Pride Month, which also makes it a great month to honor early LGBTQ scientists who made huge strides not only in their respective fields but in providing role models for LGBTQ scientists to come.

Photograph of Sara Josephine Baker taken in 1922, from the National Library of Medicine.

One of these trail-blazers was Sara Josephine Baker, born 1873 in Poughkeepsie New York. Baker was a physician and early advocate for preventive medicine and public health, primarily working with New York City’s impoverished and immigrant communities. She was the first woman to earn a doctorate in public health from NYU and Bellevue Hospital Medical College (now called the New York University School of Medicine). She was the director of New York’s Bureau of Child Hygiene, helped establish the Children’s Welfare Federation of New York, founded the American Child Hygiene Association, and held positions within numerous national and international organizations such as the Health Committee of the League of Nations. By the time of Baker’s retirement, New York City had the lowest infant mortality rate of any other large American city, in good part thanks to her work.

Photograph of children playing in the water from Healthy Children: a Volume Devoted to the Health of the Growing Child, by Sara Josephine Baker. Boston: Little, Brown and company, 1923, from the special collections of Albert R. Mann Library, Cornell University.

Sara Josephine baker was also a lesbian and an outspoken feminist. As a woman, Baker was a minority in the male-dominated medical field. She began to play with gender norms and would adopt a traditionally-masculine style of dress, often donning male-tailored suits and ties. Baker and her long-term partner Ida Wylie lived together most of their lives and would periodically hold meetings where women (many of them LGBTQ) who were also radical thinkers challenging the gender norms of their day would share their ideas over meals.

Book cover of Healthy Children,1923. (Note: Cellophane tape kept this book in circulation back in the day, but was not an ideal repair treatment. Today’s methods would instead reinforce the spine with cloth and conservation-quality adhesives. Still a lovely book cover though!).

With Healthy Children, Baker addressed the health of children of preschool age (i..e ages two to six), hoping to fill a void in the existing medical literature about this vulnerable early life stage. Baker recognized the need, especially in growing, densely-populated cities, for disease and injury prevention through family education. She intended her book to give the average parent a guide to children’s basic physical and mental health and preventive medicine in the home, though, as a physician, she was also careful to note the book was not meant to serve as a substitute to good professional medical care. Often charmingly illustrated, Healthy Children covers a range of issues from child physical and psychological development, personal hygiene, malnutrition, common diseases of childhood and how to identify them, and basic medicines that should be kept in the home.

“Child’s Romper and Creeper” illustration from Baker’s Healthy Children, meant to show how good clothing design can help maintain a healthy body temperature and to provide the child with a free range of motion.

Sara Josephine Baker was a forward-thinking physician, public health advocate and family educator who had the courage to break important new ground in both her professional and personal life. For a June Pride Month that this year commemorates a major turning point in the gay pride movement, we do well to remember this lesbian pioneer and her unflinching zeal for taking big, important steps for a better, healthier and happier world.

Sources:

britannica.com/biography/Sara-Josephine-Baker

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1470556/

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1447383/

#pride#pride month#lgbtq#public health#childrens health#medicine#vaults of mann#mannlibrary#rarebooks#special collections

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Beekeeping: From Amos to Z!

If you’re into beekeeping you likely know the name Amos Ives Root- the Ohio-born author and pioneering apiculturist who wrote “The ABC of Bee Culture” in 1879. The book in still in circulation today (although now titled “The ABC and XYZ of Bee Culture: An Encyclopedia of Beekeeping”) in its 41st edition and is affectionately nicknamed “The Beekeeper’s Bible” among bee-enthusiasts. “ABC” covers everything in regard to honey-bee rearing: from building hives to honey-harvesting, beekeeping implements, pollinator-friendly plants, biographies of noted beekeepers, and how to deal with pesky bears. A true A to Z of beekeeping!

As the story goes, Amos Root’s journey into beekeeping began on a warm August day in 1865 as a swarm of bees passed over Root’s worksite. An employee of his, recalling that Root had previously mentioned a desire to keep bees, offered to catch the swarm for him. Root was soon to discover that beekeeping is not an easy task, as his first swarm of bees was to fly off and abandon him. But he was not quick to give up! After much trial and error Root had his first successful hive, and four years later, in 1869, he decided to spread his passion for bees and founded the A.I. Root Company, producers of quality beehive and beekeeping equipment. He later went on to establish the publication “Gleanings in Bee Culture” and wrote his renowned book “The ABC of Bee Culture”. Impressively, all of Root’s accomplishments are still alive in some form. His beekeeping company would later switch to candle manufacturing, but Root Candles is still in business today and is run by Root’s great-great grandson (and produces some fine beeswax candles of course!). “Gleanings in Bee Culture” is today produced in magazine and online format and now known as “Bee Culture: The Magazine of American Beekeeping”. Last, but not least, of course the beekeeper’s bible “The ABC of Bee Culture”, while updated, is still a go-to for the modern beekeeper.

It was the efforts of early pioneers and inventors like Amos Root that laid the foundation for the modern beekeeping industry. Much has changed since Amos Roth’s time, but while the pollinators we rely on to produce over 75% of our food crop are in crisis and declining rapidly, we will need to summon that same gusto and tenacity as the early apiculture pioneers to help ensure their recovery and future health. Apiculturists like Amos Ives Root seemed to truly recognize the beauty of our pollinators and their supreme importance to all life. That isn’t a lesson we should be quick to forget!

References:

“ABC of Bee Culture”, Amos Ives Root, 1891

beeculture.com

rootcandles.com/

#specialcollections#bees#honeybees#pollinators#mann library#vaultsofmann#mannlibrary#rarebooks#scientific illustration#apiculture#beekeeping#entomology

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

On trees

“We, as a Nation, have already in the most wanton and reckless waste the world has ever known, changed our climatic conditions and wasted a good part of our heritage. The question is, shall we do what is in our power to save comfortable living conditions for ourselves and the spots of natural beauty that remain for our children. If this is to be done, a nation-wide movement must be begun immediately.”

This was a statement made by American novelist, nature writer, photographer and conservationist Gene Stratton-Porter for the book Moulding Public Opinion to Help Save our Trees written by Mabel Louise Mills and published in 1927 by the American Reforestation Association. The book tackles issues of deforestation and wild fires in the early twentieth century landscape. And while our understanding of the causes of climate change and the effects of deforestation have evolved over the years with new insights from science, many of the ideas presented in Moulding Public Opinion ring as true today as they were a hundred years ago.

The book was gifted to the Mann Library collections in 1929 by Cornell’s own Liberty Hyde Bailey—the renowned horticulturist, founder of the American Society for Horticultural Science, and the first Dean of the New York State College of Agriculture. Bailey was a proponent of the Nature Study Movement, which aimed to combine practical science with spirituality and a love for nature. This perspective is clear in Bailey’s foreword of the book, where he writes, We are the keepers of the earth. It is our privilege to see that the earth is clean and fit, and that all its resources are utilized with forethought and care. Untold generations are to follow us and they are entitled to productive soil, unspoiled vegetation, pure and abundant streams, undefiled scenery.

The publication takes a romantic yet academic tone, blending data, research, and poetry equally in an attempt to sway public opinion from all angles. The mission of the American Reforestation Association (later also known as the American Green Cross Society) was, in fact, to disseminate educational materials through whatever means necessary to foster a love for trees in the public eye— from cinema, to games, to lectures, to editorial cartoons. Founded in California in the 1920’s, the organization was a response to concerns about America’s rapidly diminishing forest cover. Its members’ organizing efforts focused on influencing public opinion through media channels and public tree plantings. And while the Association’s existence as a formal organization was short-lived, they were clearly experts in celebrity-backed publicity—aligning themselves with Hollywood names like Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford. With its pointed title, Moulding Public Opinion to Help Save Our Trees makes no secret of its ultimate goal: While serving both to document the Association’s efforts and to suggest effective tree-protecting measures and legislation, its primary aim is to tune its audience closely in to the value of trees to every area of human life.

Flip through Moulding Public Opinion’s lively illustrated pages and you’ll learn of the impact trees make to our every day work lives, to agriculture, to the entertainment industry, to the air we breathe. Presaging an issue that has become all too familiar to us in the early 21st century, it details the ways in which trees offset the carbon dioxide that humans produce.

Moulding Public Opinion however, is anything but dreary. It is a celebration of the natural world and what it gives to us. Emphasizing how science has shown the “great circles in which Nature works; the manner in which marine plants balance marine animals, as the land plants supply oxygen which the animals consume, and the animals the carbon which the plants absorb…”, it evokes the hopeful cycle of rebirth inherent in nature. Given its membership, it’s likely that the American Green Cross Society understood that tackling big environmental issues requires hard science and large swathes of good data to inform technical know-how. But it also recognized that ultimate success may well hinge more profoundly on our ability to inspire public interest and resolve. And that’s where celebrating the beauty and the poetry of the cause comes into play. With that thought, we honor the deep and adamant appreciation of the trees of our world reflected in the Society’s beautiful book, and we wish you all a Happy Arbor Day!

Additional references: https://fhsarchives.wordpress.com/tag/american-reforestation-association/

#arbor day#trees#conservation#environment#forests#mannlibrary#vaults of mann#Cornell University Library#rare books#special collections

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cow Appreciation

Cow Appreciation Day 2018 is today, July 10, We didn’t quite see it coming, but still, we’ve managed to be ready with this appreciative view of an Ayrshire Cow (”Race d’Ayr—Vache”) as illustrated by O. de Penne for the book Animaux de la ferme: Espèce Bovine, by Victor Borie (Paris, 1863). Sadly, we don’t yet know much about this beautifully illustrated book....but we do know a few things about Ayrshires, a breed that originated in southwest Scotland’s County of Ayr and is now known throughout the world for its ability to produce rich, high quality milk. The first Ayrshire arrived in America in 1822, a ship’s cow that had supplied milk during the voyage. Popular in the northeastern U.S. because of their tolerance to cold weather and ability to graze rough rocky pastures, Ayrshire cows demonstrated their strength and hardiness in a promotional stunt that the Ayrshire Breeders’ Association staged in 1929. Tomboy and Alice, two amiable Ayrshires, were walked from the association’s headquarters in Brandon, Vermont to the National Dairy Convention at St. Louis, Missouri. Both cows not only survived the trip, but went on to produce outstanding milk records for their time. For many years, the horns of Ayrshires were a hallmark of the breed, reaching at least a foot in length. Properly trained, they gracefully curved out, then up and slightly back. When polished for the show ring, these glossy projections were a spectacular sight For their impressive horns, their place in American agricultural history, and all the benefit they continue to give us--let’s have a good round of applause, please, in honor of these beauties--today and every day!

#cowappreciationday#ayrshire#dairy#farming#animal husbandry#rare books#special collections#vaults of mann#mannlibrary

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

Spider Curious

We don’t need Tolkien’s fantastically horrifying Shelob or his monstrous spiders of Mirkwood Forest to remind us that people find arachnids—even at their natural sizes—among the most fearsome creatures of the natural world. So in the spirit of spooky late October fun we've dug out a few creepy crawlies from The Natural History of Spiders and Other Curious Insects (1736), by 18th century painter and water colorist Eleazar Albin (d. 1742?).

Page through this entomological rarity, and you’ll make the acquaintance of over 180 spiders, most from England but some also from other corners of the world (South Africa, the Philippines, Suriname, among others). You won't learn their names though. Drawing from his own "ocular observation" (probably in good part via various private specimen collections), Albin provides accounts that detail the shape, color, size, and sometimes behavior of each spider depicted, but does not attempt to sort out species identification. To Albin's time, the art of taxonomy was, after all, a very young science still. Proceed to the chapter-like appendices — penned by physician Richard Mead and famed natural philosopher Robert Hooke — you get up-close-and-personal views of tarantulas, scorpions, and, somewhat incongruously, a range of fleas and lice associated with a variety of birds. The inspiration for this intriguing if somewhat discomfiting volume, as declared by author Albin in his introductory notes: A desire to provide a reliable account of the spider species that would “instruct our understanding and gratify our commendable curiosity.” Thanks to this work, and his earlier treatise, The Natural History of English Insects (London, 1720), Albin has been recognized by at least one team of science historians as "one of the great entomological book illustrators of the 18th century." (Salmon, et. al., quoted in Wikipedia).

Figure 173: A spider from the Cape of Good Hope. “These foreign large spiders have ten legs besides the forceps, all our English spiders having but eight. They are said to spin a web so strong between the branches of the trees as is able to intangle the humming-birds, which they kill and devour.” [Note: Albin mistakes two of the spider’s appendages, the short pedipalps on either side of the jaws at the top, for legs. By definition of course, spiders are 8-footed creatures].

So how did Albin—whose first paying job was that of teacher of painting and drawing in the bustling city of London—come by his success as an early pioneer of English science illustration? One lucky break came when the young artist’s life path crossed with that of Joseph Dandridge, a successful fabric pattern designer who was also respected as an amateur botanist, entomologist and collector. As Dandridge (himself a talented if possibly time-strapped illustrator) relied on Albin to render some of the choice caterpillars and other specimens gathered during expeditions across the English countryside, their collaboration provided the artist with access to a widening circle of British intellectuals, aristocrats and other wealthy patrons who would eventually become paying subscribers for several ambitious natural history projects of his own. Ultimately, Albin had five illustrated natural history works to his name, which in addition to Spiders and Insects, included, A Natural History of Birds (1731) , Natural History of English Songbirds (1737), and The History of Esculent Fish (published posthumously in 1794) , —no shabby life achievement.

Among others, the Empress of Russia. Taking care to include a celebrity-studded subscriber list in his introduction to Spiders, Albin was clearly not above stoking some 18th century FOMO as part of his marketing strategy.

While clearly adept at tapping into the wealth of England’s upper crust to make his work possible, Albin was not one born with a silver spoon in his mouth. The specific date and place of his birth are unclear, but he appears to have been born in Germany and come to London as an immigrant in either his child- or early adulthood. In London, he ended up with a large family to support (ten children in all), and their residence on Golden Square, SoHo, "next ye Green Man near Maggots Brew House," was likely not conducive to forging easy connections with the city's monied class. Yet a large family also provided some important resources. Albin's daughter, Elizabeth, and possibly his son (or son-in-law) Fortin contributed some of the lovely artwork in Albin's volumes. And according to at least one contemporaneous natural historian (James Petiver), Albin was known to use a surprisingly effective secret ingredient in mixing up the pigments for his artwork: boys' urine. No shortage of that agent in a household with five boys!

Spider no. 178: “The back, belly, legs and feelers of this large Spider were of a yellowish brown, with marks of a darker shade of the same color; its forelegs were longer than any of the others; its feelers were oddly sloped like claws of a lobster, with which it would lay hold of any thing it had a mind to.”

Albin beat some considerable odds in the unforgiving social environment of 18th century England to achieve respect as a natural history illustrator in his lifetime, but there’s a murky side to his story as well. In the late 1960's, some intrepid sleuthing by British science writer W. S. Bristowe yielded a troubling discovery: It appears that the spider illustrations in Albin's 1736 work were essentially copies of an unpublished set of "delicately executed and often excellent" illustrations by Albin's mentor Joseph Dandridge, which were found tucked away in the archives of the British Museum. Bristowe takes Albin severely to task (to the point possible with someone who’s been dead over 200 years) for failing to include even a hint of attribution to Dandridge's work is in his Spider volume. Now to be fair, Dandridge was very much still alive and kicking — "far from being in his dotage" as Bristowe puts it — when Albin published Spiders, and Albin's appropriation appears to have elicited none of the justifiable outrage one might have expected from his mentor or any of his other contemporaries. At least not anything that's been recorded in the history books.

And for your frontispiece, why not a put portrait of the author riding a fine horse among an array of mites, scorpions, tarantulas and other spiders!? One can’t, of course, help wondering about he inspiration behind this composition. An eccentric sense of grandeur ? A surreal sense of humor? Or maybe a need to express some wry commentary on the way this particular project had taken over the author’s life? Your guess!

Regardless of the specific story behind his Spider work, it’s clear that Albin labored greatly in life to achieve the results he did. Perhaps Joseph Dandridge felt sorry enough for hard-toiling Albin—and appreciated his zeal for the natural history project enough—to cut his erstwhile mentee a generous break and forgive him his piracy; perhaps Dandridge owed Albin some kind of intellectual debt stemming from their years of collaboration; or perhaps Albin contributed to Dandridge's original spider drawings in ways that he himself had not yet been able to acknowledge.

We may never know the full story behind this apparent act of 18th century intellectual property theft. But it's a good cautionary tale in the month of October in any case. While the entomologically unenlightened among us may still find spiders profoundly scary creatures, there's nothing like a cry of plagiarism to send shivers of horror into both the halls of academia and the world of publishing. And almost surely, that is a very good thing.

Additional references:

Albin, Eleazar. A Natural History of English Insects. 1720 Bristowe, W. S., "The Life and Work of a Great English Naturalist: Joseph Dandridge," Entomologist's Gazette, Vol. 18, No. 2 (April 24, 1967), pp. 71-89 Bristowe, W. S., "More About Joseph Dandridge and His Friends James Petiver and Eleazar Albin," Entomologists Gazette, Vol. 18, Nos. 3 & 4, pp. 197-201. Osborne, Peter (2004): "Albin, Eleazar (d. 1742?)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press. Weiss, Harry B., "Two Entomologists of the Eighteenth Century--Eleazar Albin and Moses Harris," The Scientific Monthly, Vol. 23, No. 6 (Dec., 1926), pp. 558-564

Wikipedia:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_Dandridge https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eleazar_Albin

#spider#arachnid#insect#entomology#natural history#rarebooks#mannlibrary#vaultsofmann#cornelluniversitylibrary

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marigolds in May

Caltha palustris (Marsh Marigold), from Flora Londinensis, William Curtis, London, 1777-1787

Take a stroll near the boggy fields, glens, and wet woodland edges around the Cornell University campus in spring and you’re likely to see some of these darlings take their place—in bunches—alongside the May flowers of the Finger Lakes. Caltha palustris —aka marsh marigold —is a wildflower native to a large swathe of the temperate Northern Hemisphere. There’s something about stumbling across a patch of these deeply yellow blossoms, nestled as they are against their softly curved, verdantly green leaves, that’s sure to soften any heart and brighten any mood. We think it no wonder that they caught the eye of English naturalist and botanical illustrator William Curtis back in the day.

William Curtis (1746-1799) is one of the most famous naturalists of eighteenth century England.Originally trained as an apothecary, Curtis turned to the study of natural history and botany as his true calling while in his early twenties. In his lifetime, William Curtis was known as a prolific innovator and the driving force behind some of the most ambitious natural history projects of his time. Curtis himself probably derived his greatest satisfaction from the Flora Londinensis, a delightful series of illustrated descriptions of native plants that Curtis identified within a ten-mile radius of the city of London. It includes both native flowers grown in local gardens as well as a wide variety of far less showy common wild flowers and grasses. Published incrementally over time to eventually make up a two volume work, Flora Londinensis revealed Curtis's deep love of the natural landscape and earned him his modern-day reputation as one of England's earliest conservationists. It’s one of our favorite treasures in the Mann Library special collections!

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

Death in the Pot!

For a large serving of the sinister and spooky this Halloween, dig no further than this morbid title from Mann’s Special Collections: Deadly Adulteration and Slow Poisoning or, Disease and Death in the Pot and the Bottle. Published in London, around 1829 by an anonymous author self-described as “An Enemy of Fraud and Villainy”, this volume caused quite a stir at the time. While the title may suggest some kind of “How-To” for the murderously inclined, this work was actually intended to publicize the use of chemicals and unsafe practices in the production of common food items such as tea, flour and medicines.

Many later historians of food safety believe this work was actually the last-ditch effort of Friedrich Accum to get his message across to ordinary citizens. Accum was a German chemist who wrote in English and whose many scientific publications were influential in the popularization of chemistry during this era. Earlier in 1820, Accum had published his “Treatise on Adulteration of Food” to both great acclaim – and outrage. The cover was imprinted with a skull-and-crossbones above a spider sitting in the center of an intricate spiderweb.

And what about that catchy headline: Death in the Pot? This is a Biblical reference (2 Kings 4:40), which started to appear in the early 1700s in medical treatises and books about food contamination.

For a closer look at our creepy collections you can request to view both volumes from Mann’s special collections: http://mannlib.cornell.edu/use/collections/special/registration

Deadly Adulteration and Slow Poisoning, Anonymous, c1829, Call Number TX563.D27.

A Treatise on Adulterations of Food and Culinary Poisons, Accum, Friedrich Christian, 1820, Call Number TX 563. A17 1820.

#pagefrights#food#contamination#public health#rare books#special collections#mannlibrary#vaultsofmann

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Heavy Metal Moth!

Death's Head Hawkmoth (Acherontia atropos), aptly named for the skull image on its thorax. SciArt by Janet Harvey Kelman for her Butterflies and Moths (1910). In @biodivlibrary via @mannlibrary.

#femaleillustrators#sciart#womenshistorymonth#deathsheadhawkmoth#historicalsciart#femaleartists#moths#entomology#scientificillustration#womeninhistsciart#hawkmoth#histsciart#bhlib#art#naturalhistory#scientificart#5womenartists#biodiversity#womeninscience#womeninnaturalhistory#science

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Challenging the Deep

In December 1872, the H.M.S. Challenger, a re-tooled British naval ship outfitted with some of the most sophisticated scientific equipment of the times, left Portsmouth, England to take a crew of sailors and scientists around the globe on what is today widely regarded as the first major oceanographic expedition in modern science. In celebration of its launch in a cold winter 144 years ago, we excerpt from our Fall 2016 exhibit “Challenging the Deep: The Voyage & Revelations of H.M.S. Challenger” to give this historic voyage our December spotlight.

H.M.S Challenger Amongst the Ice February 14th 1874, by B. Shepard.

Funded by the Royal Society of London, the Challenger set out to the explore the world’s oceans through sounding and dredging – measuring the depth of the water and bringing up material from the ocean floor. But while this main mission was primarily geological in scope, her crew discovered, documented, and collected samples of thousands of marine creatures. The scientific crew made meticulous drawings and preserved specimens in jars, both of which became objects of intense study by English and European scientists for years after the expedition.

A goosefish (Lophius naresi) in print…

…and preserved.

Among the advanced scientific equipment on board the Challenger, was a full photographic darkroom and precision stereo microscopes. Planktonic creatures like this shrimp larva – only a few millimeters long – could not have been recorded in such detail before such optics existed.

The Challenger expedition produced so much information that its findings are collected in a 50 volume report that took 19 years to publish in its entirety. This vast wealth of data about the ocean and its inhabitants is still searched through and referenced by 21st century researchers, forming the first core text of the modern science of oceanography.

The Challenger’s laboratory

“Challenging the Deep: The Voyage & Revelations of H.M.S. Challenger” looks at the voyage, the discoveries her crew made while dredging and sounding the deepest parts of the world's oceans, and the legacy of oceanic science that has followed in her wake. The exhibit is on display in the Mann Library lobby through March 2017.

400 notes

·

View notes