#medieval history

Text

all RIGHT:

Why You're Writing Medieval (and Medieval-Coded) Women Wrong: A RANT

(Or, For the Love of God, People, Stop Pretending Victorian Style Gender Roles Applied to All of History)

This is a problem I see alllll over the place - I'll be reading a medieval-coded book and the women will be told they aren't allowed to fight or learn or work, that they are only supposed to get married, keep house and have babies, &c &c.

If I point this out ppl will be like "yes but there was misogyny back then! women were treated terribly!" and OK. Stop right there.

By & large, what we as a culture think of as misogyny & patriarchy is the expression prevalent in Victorian times - not medieval. (And NO, this is not me blaming Victorians for their theme park version of "medieval history". This is me blaming 21st century people for being ignorant & refusing to do their homework).

Yes, there was misogyny in medieval times, but 1) in many ways it was actually markedly less severe than Victorian misogyny, tyvm - and 2) it was of a quite different type. (Disclaimer: I am speaking specifically of Frankish, Western European medieval women rather than those in other parts of the world. This applies to a lesser extent in Byzantium and I am still learning about women in the medieval Islamic world.)

So, here are the 2 vital things to remember about women when writing medieval or medieval-coded societies

FIRST. Where in Victorian times the primary axes of prejudice were gender and race - so that a male labourer had more rights than a female of the higher classes, and a middle class white man would be treated with more respect than an African or Indian dignitary - In medieval times, the primary axis of prejudice was, overwhelmingly, class. Thus, Frankish crusader knights arguably felt more solidarity with their Muslim opponents of knightly status, than they did their own peasants. Faith and age were also medieval axes of prejudice - children and young people were exploited ruthlessly, sent into war or marriage at 15 (boys) or 12 (girls). Gender was less important.

What this meant was that a medieval woman could expect - indeed demand - to be treated more or less the same way the men of her class were. Where no ancient legal obstacle existed, such as Salic law, a king's daughter could and did expect to rule, even after marriage.

Women of the knightly class could & did arm & fight - something that required a MASSIVE outlay of money, which was obviously at their discretion & disposal. See: Sichelgaita, Isabel de Conches, the unnamed women fighting in armour as knights during the Third Crusade, as recorded by Muslim chroniclers.

Tolkien's Eowyn is a great example of this medieval attitude to class trumping race: complaining that she's being told not to fight, she stresses her class: "I am of the house of Eorl & not a serving woman". She claims her rights, not as a woman, but as a member of the warrior class and the ruling family. Similarly in Renaissance Venice a doge protested the practice which saw 80% of noble women locked into convents for life: if these had been men they would have been "born to command & govern the world". Their class ought to have exempted them from discrimination on the basis of sex.

So, tip #1 for writing medieval women: remember that their class always outweighed their gender. They might be subordinate to the men within their own class, but not to those below.

SECOND. Whereas Victorians saw women's highest calling as marriage & children - the "angel in the house" ennobling & improving their men on a spiritual but rarely practical level - Medievals by contrast prized virginity/celibacy above marriage, seeing it as a way for women to transcend their sex. Often as nuns, saints, mystics; sometimes as warriors, queens, & ladies; always as businesswomen & merchants, women could & did forge their own paths in life

When Elizabeth I claimed to have "the heart & stomach of a king" & adopted the persona of the virgin queen, this was the norm she appealed to. Women could do things; they just had to prove they were Not Like Other Girls. By Elizabeth's time things were already changing: it was the Reformation that switched the ideal to marriage, & the Enlightenment that divorced femininity from reason, aggression & public life.

For more on this topic, read Katherine Hager's article "Endowed With Manly Courage: Medieval Perceptions of Women in Combat" on women who transcended gender to occupy a liminal space as warrior/virgin/saint.

So, tip #2: remember that for medieval women, wife and mother wasn't the ideal, virgin saint was the ideal. By proving yourself "not like other girls" you could gain significant autonomy & freedom.

Finally a bonus tip: if writing about medieval women, be sure to read writing on women's issues from the time so as to understand the terms in which these women spoke about & defended their ambitions. Start with Christine de Pisan.

I learned all this doing the reading for WATCHERS OF OUTREMER, my series of historical fantasy novels set in the medieval crusader states, which were dominated by strong medieval women! Book 5, THE HOUSE OF MOURNING (forthcoming 2023) will focus, to a greater extent than any other novel I've ever yet read or written, on the experience of women during the crusades - as warriors, captives, and political leaders. I can't wait to share it with you all!

#watchers of outremer#medieval history#the lady of kingdoms#the house of mourning#writing#writing fantasy#female characters#medieval women#eowyn#the lord of the rings#lotr#history#historical fiction#fantasy#writing tip#writing advice

29K notes

·

View notes

Text

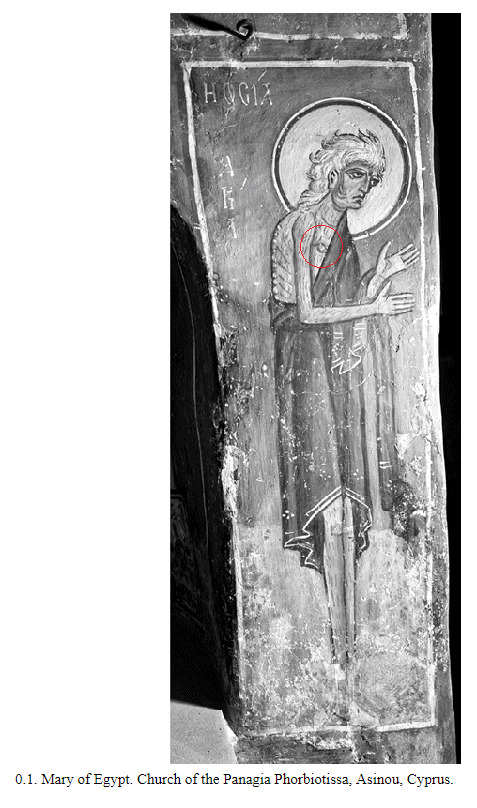

I started reading Roland Betancourt's Byzantine Intersectionality because it has a chapter on transwomen, but it turns out that the book is heavily focused on transmasculinity and race in the Byzantine world.

Specifically I wanted to show you this discussion on artistic representation of top surgery and the likelihood that this actually represents top surgery.

Anyway this is really fucking cool

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

Medieval Toy Unearthed in Poland

A 800-year-old horse figurine was found during an excavation conducted as part of the construction of a new fire station in Toruń, a medieval town on the Vistula River in north-central Poland. The small clay horse was glazed and has a hole in its underside. Researchers think a stick may have fit into the hole so that playing children could pretend to make the horse gallop or use it as a puppet.

#Medieval Toy Unearthed in Poland#A 800-year-old horse figurine#Toruń#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#medieval history

872 notes

·

View notes

Text

Available as an open-access PDF via the publisher or @jstor, this sourcebook takes in a wide range of genres to look at histories of disability in medieval Europe. You can also get a hard copy for under $30 if you feel like supporting an indie publisher. Any royalties are donated to causes related to disability justice.

2K notes

·

View notes

Link

"The desire to be 'accurate' suddenly disappears when sex isn't involved and it is actual interesting day to day minutiae," says Eleanor Janega, a medieval historian who teaches at the London School of Economics. "If the ('Game of Thrones') world was historically accurate, why isn't every single noble house or castle absolutely covered by huge gaudy, colourful murals? Why is it that this form of historical accuracy isn't important, but showing rape as endemic is?"

Other historians point out that, as prurient and gasp-worthy as something like a crude C-section death is, such butchery wasn't as prevalent as storytellers would have you believe.

"They were very keen on protecting mothers from harm," medieval history scholar Sara McDougall told Slate.

Texts from the time indicate that such extreme measures would usually be performed on women who had already died -- not, as in "House of the Dragon," a fully awake and alert woman with no clue what was about to happen to her.

[...]

Janega points out that, while medieval times were certainly not overkind to women or anyone else who wasn't rich, powerful and male, they weren't the burlesque of suffering we're so used to seeing on screen.

"'Accuracy' is always focusing on the distasteful aspects of a society, but never the pleasurable ones," she says. "(It) somehow always encompasses sexual violence and never things like, for example, the three field system, or fishing weirs. They don't really show how women other than the nobility are a dynamic part of the medieval workforce. Women are found in pretty much every facet of medieval work: as blacksmiths, running shops, brewing beer, in cloth production, running bath houses or in trading delegations addressing the court."

12K notes

·

View notes

Text

Medieval Europeans regarded embroidery as an art, much as we today consider painting. It was considered a female task, and even chambermaids were expected to be competent in it. Yet it was a coveted line of work, as one early Irish law tract stated that "the woman who embroiders earns more profit even than queens." Embroiderers could find employment with professional clothing makers or in tapestry workshops.

By the thirteenth century, given that embroidery was held in high esteem and could bring in money, the field contained plenty of men as well. In England, over time women come up less frequently on the lists of embroiderers than men and more often in conjunction with a husband, even when their work was exceptional. In May 1317 "Rose, the wife of John de Bureford, citizen and merchant of London," sold "an embroidered cope for the choir" to the French queen Isabella (ca. 1295-1358), who gave it as a gift "to the Lord High Pontiff." Rose was clearly a very skilled artist, since she was commissioned by the queen, but was not skilled enough to be named as an artist in her own right. We don't know how many other working embroiderers were subsumed into their husbands' workshops with even their first names lost to us. Once a field became truly profitable, men nudged women out of it. It was all well and good to let ladies have fun with a needle and thread. But if there was cash to be made, men suddenly showed up front and center and excluded women from the role.

-Eleanor Janega, The Once and Future Sex: Going Medieval on Women’s Roles in Society

#eleanor janega#womens history#art history#embroidery#the more things change the more they stay the same#medieval history#men menning

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Was minding my own business today when my brain suddenly recalled a history text I read years ago back in college describing homosexuality in medieval monasteries. Being an isolated population of entirely men comprised of the cast-off and spare sons of local lords and nobles, it was not uncommon for the monks to rampantly bugger the hell out of each other.

Then, in a display of rules-lawyering that medieval monks were infamous for, the monks would Confess their recent “sins” to their lover so they could Absolve each other. That way, they could walk around with a spiritually clean slate until the next time they got together with the hot monk in the next cell over and “sinned” again. Genius. Outstanding. Gaming the system. No notes.

#History#LGBTQ History#Medieval History#Medieval Monk#Queer History#Shower Thoughts#yes this is real#and if memory serves the book's author also found it as funny as I did

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Loyalty to Monarchs or Ruling Houses:A family loyal to a specific monarch might adopt characters associated with that ruler's heraldic symbols.

For instance, during the Tudor period in England, supporters like the red dragon were often used to express loyalty to the Tudor dynasty.

558 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wild Goats, Horns Interlocked

Detail from “The Ashmole Bestiary”

1511 (Bodleian Library)

#art history#art#history#european art#medieval#medieval art#middle ages#animals#catholic art#illuminated manuscript#illustrated manuscript#early medieval#medieval manuscripts#medieval history#goats

765 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gold rings from Anglo-Saxon England, 8th-10th century AD

from The British Museum

9K notes

·

View notes

Text

So here's one of the coolest things that has happened to me as a Tolkien nut and an amateur medievalist. It's also impacted my view of the way Tolkien writes women.

Here's Carl Stephenson in MEDIEVAL FEUDALISM, explaining the roots of the ceremony of knighthood:

"In the second century after Christ the Roman historian Tacitus wrote an essay which he called Germania, and which has remained justly famous. He declares that the Germans, though divided into numerous tribes, constitute a single people characterised by common traits and a common mode of life. The typical German is a warrior. [...] Except when armed, they perform no business, either private or public. But it is not their custom that any one should assume arms without the formal approval of the tribe. Before the assembly the youth receives a shield and spear from his father, some other relative, or one of the chief men, and this gift corresponds to the toga virilis among the Romans--making him a citizen rather than a member of a household" (pp 2-3).

Got it?

Remember how Tolkien was a medievalist who based his Rohirrim on Anglo-Saxon England, which came from those Germanic tribes Tacitus was talking about?

Stephenson argues that the customs described by Tacitus continued into the early middle ages eventually giving rise to the medieval feudal system. One of these customs was the gift of arms, which transformed into the ceremony of knighthood:

"Tacitus, it will be remembered, describes the ancient German custom by which a youth was presented with a shield and a spear to mark his attainment of man's estate. What seems to the be same ceremony reappears under the Carolingians. In 791, we are told, Charlemagne caused Prince Louis to be girded with a sword in celebration of his adolescence; and forty-seven years later Louis in turn decorated his fifteen-year-old son Charles "with the arms of manhood, i.e., a sword." Here, obviously, we may see the origin of the later adoubement, which long remained a formal investiture with arms, or with some one of them as a symbol. Thus the Bayeux Tapestry represents the knighting of Earl Harold by William of Normandy under the legend: Hic Willelmus dedit Haroldo arma (Here William gave arms to Harold). [...] Scores of other examples are to be found in the French chronicles and chansons de geste, which, despite much variation of detail, agree on the essentials. And whatever the derivation of the words, the English expression "dubbing to knighthood" must have been closely related to the French adoubement" (pp 47-48.)

In its simplest form, according to Stephenson, the ceremony of knighthood included "at most the presentation of a sword, a few words of admonition, and the accolade."

OK. So what does this have to do with Tolkien and his women? AHAHAHAHA I AM SO GLAD YOU ASKED. First of all, let's agree that Tolkien, a medievalist, undoubtedly was aware of all the above. Second, turn with me in your copy of The Lord of the Rings to chapter 6 of The Two Towers, "The King of the Golden Hall", when Theoden and his councillors agree that Eowyn should lead the people while the men are away at war. (This, of course, was something that medieval noblewomen regularly did: one small example is an 1178 letter from a Hospitaller knight serving in the Latin kingdom of Jerusalem which records that before marching out to the battle of Montgisard, "We put the defence of the Tower of David and the whole city in the hands of our women".) But in The Lord of the Rings, there's a little ceremony.

"'Let her be as lord to the Eorlingas, while we are gone.'

'It shall be so,' said Theoden. 'Let the heralds announce to the folk that the Lady Eowyn will lead them!'

Then the king sat upon a seat before his doors and Eowyn knelt before him and received from him a sword and a fair corselet."

I YELLED when I realised what I was reading right there. You see, the king doesn't just have the heralds announce that Eowyn is in charge. He gives her weapons.

Theoden makes Eowyn a knight of the Riddermark.

Not only that, but I think this is a huge deal for several reasons. That is, Tolkien knew what he was doing here.

From my reading in medieval history, I'm aware of women choosing to fight and bear arms, as well as becoming military leaders while the men are away at some war or as prisoners. What I haven't seen is women actually receiving knighthood. Anyone could fight as a knight if they could afford the (very pricy) horse and armour, and anyone could lead a nation as long as they were accepted by the leaders. But you just don't see women getting knighted like this.

Tolkien therefore chose to write a medieval-coded society, Rohan, where women arguably had greater equality with men than they did in actual medieval societies.

I think that should tell us something about who Tolkien was as a person and how he viewed women - perhaps he didn't write them with equal parity to men (there are undeniably more prominent male characters in The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit, at least, than female) but compared to the medieval societies that were his life's work, and arguably even compared to the society he lived in, he was remarkably egalitarian.

I think it should also tell us something about the craft of writing fantasy.

No, you don't have to include gut wrenching misogyny and violence against women in order to write "realistic" medieval-inspired fantasy.

Tolkien's fantasy worlds are DEEPLY informed by medieval history to an extent most laypeople will never fully appreciate. The attitudes, the language, the ABSOLUTELY FLAWLESS use of medieval military tactics...heck, even just the way that people travel long distances on foot...all of it is brilliantly medieval.

The fact that Theoden bestows arms on Eowyn is just one tiny detail that is deeply rooted in medieval history. Even though he's giving those arms to a woman in a fantasy land full of elves and hobbits and wizards, it's still a wonderfully historically accurate detail.

Of course, I've ranted before about how misogyny and sexism wasn't actually as bad in medieval times as a lot of people today think. But from the way SOME fantasy authors talk, you'd think that historical accuracy will disappear in a puff of smoke if every woman in the dragon-infested fantasy land isn't being traumatised on the regular.

Tolkien did better. Be like Tolkien.

#tolkien#middle earth#jrr tolkien#lord of the rings#lotr#the lord of the rings#eowyn#writing fantasy#fantasy#female characters#writing#historical fiction#medieval women#medieval history#medieval#history#womens history

8K notes

·

View notes

Text

Orava Castle, a medieval (13th century) stronghold on an extremely high and steep cliff by the Orava River, Slovakia.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

"That Æthelswith was the bestower of such gifts is consistent with the other things we know about her. In 868 she witnessed a West-Saxon charter, in which she made a grant of fifteen hides of her own land in Berkshire. She also witnessed all of her husband King Burgred’s charters. Though we only see glimpses of her influence, Æthelswith, like other Mercian queens before her, was a politician.

In 874, twenty one years after Æthelswith married Burgred, the royal couple were forced out of their kingdom by an encroaching Viking army. They fled together to safety in Rome. While Burgred died soon after they arrived, Æthelswith outlived him for another decade, which she spent in Italy.

Queen Æthelswith passed away in 888 in Pavia, and was laid to rest there. She may have been undertaking a pilgrimage when she died. Her body and the ring that she once bestowed were both buried underground a thousand miles apart. And they say medieval women didn’t travel…"

#Æthelswith#history#women in history#women's history#9th century#english history#queens#leaders#english queens#anglo saxon history#anglo saxon england#medieval women#medieval history#middle ages#medieval#archeology

249 notes

·

View notes

Text

But that’s my emotional support 12th century nun music :(

#I’m still thinking about her ok#hildegard von bingen#medieval#music#medievalcore#bardcore#medieval history#history#meme#i’ll be on my merry way now

309 notes

·

View notes

Text

Medieval peasants did not behave in a manner modern social scientists think of as optimal for their circumstances.

--Barbara A. Hanawalt, The Ties That Bound: Peasant Families in Medieval England.

(Dr. Hanawalt explains that there is no real evidence that English peasants were living in or even particularly acknowledging the existence of extended kinship groups in the 14th-15th century, no matter how much anthropologists think they should have been.)

#barbara a hanawalt#the ties that bound: peasant families in medieval england#history#england#kinship#medieval history#english did not have a word for COUSIN until borrowing it from french#english did not have a word for AUNT#there was a word for a father's brother#for nuclear family#and that was IT

213 notes

·

View notes

Text

[I know lions weren’t a totally alien concept in medieval Europe, but I do find it quite funny how they were… lionised]

208 notes

·

View notes