#medieval women

Text

all RIGHT:

Why You're Writing Medieval (and Medieval-Coded) Women Wrong: A RANT

(Or, For the Love of God, People, Stop Pretending Victorian Style Gender Roles Applied to All of History)

This is a problem I see alllll over the place - I'll be reading a medieval-coded book and the women will be told they aren't allowed to fight or learn or work, that they are only supposed to get married, keep house and have babies, &c &c.

If I point this out ppl will be like "yes but there was misogyny back then! women were treated terribly!" and OK. Stop right there.

By & large, what we as a culture think of as misogyny & patriarchy is the expression prevalent in Victorian times - not medieval. (And NO, this is not me blaming Victorians for their theme park version of "medieval history". This is me blaming 21st century people for being ignorant & refusing to do their homework).

Yes, there was misogyny in medieval times, but 1) in many ways it was actually markedly less severe than Victorian misogyny, tyvm - and 2) it was of a quite different type. (Disclaimer: I am speaking specifically of Frankish, Western European medieval women rather than those in other parts of the world. This applies to a lesser extent in Byzantium and I am still learning about women in the medieval Islamic world.)

So, here are the 2 vital things to remember about women when writing medieval or medieval-coded societies

FIRST. Where in Victorian times the primary axes of prejudice were gender and race - so that a male labourer had more rights than a female of the higher classes, and a middle class white man would be treated with more respect than an African or Indian dignitary - In medieval times, the primary axis of prejudice was, overwhelmingly, class. Thus, Frankish crusader knights arguably felt more solidarity with their Muslim opponents of knightly status, than they did their own peasants. Faith and age were also medieval axes of prejudice - children and young people were exploited ruthlessly, sent into war or marriage at 15 (boys) or 12 (girls). Gender was less important.

What this meant was that a medieval woman could expect - indeed demand - to be treated more or less the same way the men of her class were. Where no ancient legal obstacle existed, such as Salic law, a king's daughter could and did expect to rule, even after marriage.

Women of the knightly class could & did arm & fight - something that required a MASSIVE outlay of money, which was obviously at their discretion & disposal. See: Sichelgaita, Isabel de Conches, the unnamed women fighting in armour as knights during the Third Crusade, as recorded by Muslim chroniclers.

Tolkien's Eowyn is a great example of this medieval attitude to class trumping race: complaining that she's being told not to fight, she stresses her class: "I am of the house of Eorl & not a serving woman". She claims her rights, not as a woman, but as a member of the warrior class and the ruling family. Similarly in Renaissance Venice a doge protested the practice which saw 80% of noble women locked into convents for life: if these had been men they would have been "born to command & govern the world". Their class ought to have exempted them from discrimination on the basis of sex.

So, tip #1 for writing medieval women: remember that their class always outweighed their gender. They might be subordinate to the men within their own class, but not to those below.

SECOND. Whereas Victorians saw women's highest calling as marriage & children - the "angel in the house" ennobling & improving their men on a spiritual but rarely practical level - Medievals by contrast prized virginity/celibacy above marriage, seeing it as a way for women to transcend their sex. Often as nuns, saints, mystics; sometimes as warriors, queens, & ladies; always as businesswomen & merchants, women could & did forge their own paths in life

When Elizabeth I claimed to have "the heart & stomach of a king" & adopted the persona of the virgin queen, this was the norm she appealed to. Women could do things; they just had to prove they were Not Like Other Girls. By Elizabeth's time things were already changing: it was the Reformation that switched the ideal to marriage, & the Enlightenment that divorced femininity from reason, aggression & public life.

For more on this topic, read Katherine Hager's article "Endowed With Manly Courage: Medieval Perceptions of Women in Combat" on women who transcended gender to occupy a liminal space as warrior/virgin/saint.

So, tip #2: remember that for medieval women, wife and mother wasn't the ideal, virgin saint was the ideal. By proving yourself "not like other girls" you could gain significant autonomy & freedom.

Finally a bonus tip: if writing about medieval women, be sure to read writing on women's issues from the time so as to understand the terms in which these women spoke about & defended their ambitions. Start with Christine de Pisan.

I learned all this doing the reading for WATCHERS OF OUTREMER, my series of historical fantasy novels set in the medieval crusader states, which were dominated by strong medieval women! Book 5, THE HOUSE OF MOURNING (forthcoming 2023) will focus, to a greater extent than any other novel I've ever yet read or written, on the experience of women during the crusades - as warriors, captives, and political leaders. I can't wait to share it with you all!

#watchers of outremer#medieval history#the lady of kingdoms#the house of mourning#writing#writing fantasy#female characters#medieval women#eowyn#the lord of the rings#lotr#history#historical fiction#fantasy#writing tip#writing advice

29K notes

·

View notes

Text

“You just wrote your medieval fantasy setting to have medieval gender roles and homophobia and prejudice because you secretly fantasize about being able to be sexist and homophobic in a land with no PoC without any pushback! It’s fantasy, there’s dragons and wizards, it doesn’t have to have prejudice unless you, the writer, want it like that! In *my* D&D setting, there’s no sexism or homophobia, so that gay transgender women of all races can be holy knights fighting to protect the good kingdom from the endless hordes of the evil dark race that has threatened its borders for a thousand years!”

#writing#medieval fantasy#medieval women#fantasy#d&d#d&d 5e#dungeons and dragons#ttrpg#books#novels#worldbuilding

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

"Burginda’s letter is instructing the young man in his spiritual endeavours, and the contents of the (albeit short) letter reveal that she was highly educated and well-read. Written in a period that many still refer to erroneously as an intellectual ‘Dark Ages’, Burginda’s letter uses Greek words, utilises biblical exegesis, imitates Christian poetry like the fifth-century Psychomachia of Prudentius, and references both the sixth-century Italian poet Arator and the classical Roman poet Virgil. It also contains a reworking of a description of heaven found in a Latin poem from Africa that dates to c. 500. Burginda was clearly a very well-read intellectual.

This letter can be used as an example to refute many popular misconceptions about the early middle ages. The first misconception is that antique texts were neglected or unknown in this period. The second misconception is that medieval women were uneducated and unintellectual. The third misconception is that there was little or no intellectual transmission between Africa and Europe in this period. Burginda’s letter proves all these assumptions false. Not bad for two paragraphs of Latin."

#burginda#history#women in history#women's history#8th century#england#english history#female writers#herstory#middle ages#medieval#medieval women

446 notes

·

View notes

Text

comfort boob grab

in an astrological-astronomical manuscript, germany, ca. 1445

source: Berlin, Staatsbibliothek, Ms. germ. fol. 244, fol. 142r

#iykyk#medieval art#medieval women#illuminated manuscripts#15th century#illumination#medieval#astrology#medieval fashion

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Matilda, Eleanor, and Joanna - retrospring request for the Angevin daughters

#Angevin empire#Plantagenets#Matilda of Saxony#Eleanor of England queen of Castile#Joanna of Sicily#12th century#medieval#medieval women#requests#my art

123 notes

·

View notes

Text

Saint Hedwig discovers a hedgehog, 1353.

Here's the source, which contains entertaining historical info about monks & nuns keeping pets: http://inpress.lib.uiowa.edu/Feminae/DetailsPage.aspx?Feminae_ID=46288

#medieval#medieval manuscripts#manuscripts#art#medieval art#medieval women#women#saint hedwig#manuscript#funny#hedgehog#cute#adorable

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

I drew some fun medieval ladies! :)

Drawing historically inspired clothing is so fun! I sort of flubbed the peasant woman's outfit though 😅

#art#my art#artists on tumblr#art by me#traditional art#pencil sketch#oc#original content#original art#original character#medieval#medieval times#character design#medieval character#medieval women#fantasy#fantasy character#fantasy character design#noblewoman

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mistakes in Magnificent Century part I

In part I I would like to speak about mistakes they made while writing characters. Their ages, titles, origins etc.

Let's start with Ayse Hafsa Sultan:

Several things about her were done wrong. First of all, She was not Crimean princess. There are two possibilities that although contradicts one another counters her royal origin. 1. There was another concubine named Ayse,who was daughter of Crimean khan, while she was called Ayse Hafsa for that reason 2.( I agree with that possibility more ) there was no concubine from Crimean family Sultan Bayazid would never let Selim, who was not his favourite, to gain such allie, nor would khan of Crimea risk to marry her daughter to non-favoired prince. Besides, Selim did not have much of a support from Crimea during his Rebellion.

As we more or less agreed that Ayse Hafsa was not Crimean, now we have to agree on where she was from. Legendary mother of the Magnificent sultan was actually converted slave of Caucasian origin, therefore she was either Circassian or Georgian.

Third thing about her is her title. Screenwriters both demoted and promoted her in this case. She was not "Valide Sultan" as we know today, first holder of that title would be Nurbanu 40 years after her death. She was Sultan and respected mother Padisah yes,but those two honours never joined for her. She was simply " Mother of Sultan Suleiman",who had title of Sultan instead of Hatun. While Nurbanu was full fledged "Valide Sultan" and was addressed so. Despite not being Valide Sultan, she was the first slave in Ottoman history, who was elevated to Status of Sultan that was never underlined in the show.

Other mistakes about her are how they represented her pre-1520 life, which I will discuss in Part 3 about "Titles, ranks and traditions" and her relationship with daughters- in law, that will be discussed in part 2, that will be specifically about relationships.

2. Ages of Suleiman's sister.

In the show Suleiman Seems to be older, followed by Sah or beyhan, Fatma being somewhat middle and Hatice as baby of the Family, while actually going backwards. One thing I want to make clear is that all the full sisters of sultan were older than them(before 1522 of course), half sister could have been either younger or older. So Fatma, Beyhan and Hatice despite being portrayed as younger sisters were definitely older. A more accurate sequence would be:

Hatice- c. 1490

Fatma: 1491-92

Beyhan: most likely 1493

Suleiman: 1494

Hafsa: 1495

Sah-huban: 1500

Suleiman also had at least three brothers orhan, salih, who seemed to be older than Suleiman, a sister who likely died during childhood and Shehzade sultan or Hanim sultan, who was either another sister or perhaps she never existed and all the little sources about her is actually about hatice.

3. Origin of Sah Huban Sultan.

She was not the daughter of Hafsa and older sister of Hatice, she was actually the youngest of shown siblings,born as the only child of an unknown concubine registered as " The mother of Sah Huban Sultan".

4. Origin of Hurrem

In the show she was portrayed to be Crimean and was addressed as " Russian slave" numerous times. However, she was actually from Ruthenia, it was then part of the Polish crown, now it's part of Ukraine, so definitely not Russian.

5. Forgotten Children

Apart from the six children that were shown in the show, Suleiman had four other children. Three sons and a daughter.

Shehzade Mahmud and Shehzade Murad were born before Hurrem arrived and had different mothers. Mahmud was the eldest born in 1512, Murad was younger than Mustafa born in 1519. Raziye was born between 1513 and 1518, but most likely she was born in 1513-14 as she seems to be the second child and old enough to be considered Mahidevran's(which is by the way false). All three of them died in 1521 as the result of the plague.

The fourth child Shehzade Abdullah was born as the fourth child of Hurrem and Suleiman, born in 1525 and died in 1528. His date of birth is kind of troubling, some historians argue if he was born in 1525,some even say he was Mihrimah's twin, but considering no birth of twins registered, definite ages of other kinds and his appearance in Hurrem's letters Abdullah seems to be born in 1525.

6. Nurbanu's Triplets

Mistakes about the birth of Selim I daughters are more or less clear, let's speak about Selim II as well.

In the show, triplets- Sah, Esmahan and Gevherhan were introduced as younger twin sisters of shehzade Murad. In reality, all three were older but certainly not twins, Sah was not even Nurbanu's daughter, she shared the birth year with Gevherhan though, both were born in c.1544, then was Esmahan in 1545, Murad in 1546, at this point Nurbanu stopped giving birth to any more kids, last of Selim II's kids was Fatma born in 1559.

7. Origin and death of Gulfem hatun

In "Magnificent century" Gulfem is portrayed as Suleiman's first concubine, who bore a son,but lost everything after he died. In reality, Gulfem was one of the highest ranking harem managers, whom Suleiman trusted Hurrem to, she was overseeing her education and well-being, bonding with future Haseki Sultan in the process. Gulfem actually became the closest friend and Confidant of Hurrem, about which I will speak about in part II.

Her death was also portrayed inaccurately. She was not killed for the attempted murder of Suleiman, The closest rumor to it is him executing Gulfem for rejecting him,but she actually died of old age. Suleiman had no reason to execute Gulfem,there is a version were Gulfem exchanges her Night to other concubine to for money to build complex,but there are so many flaws in this theory:

1. There was no such thing in harem as "my turn and your turn"

2. It was strictly against the traditions to call harem servant, especially one from the highest ranks, and considering when it happened in kate nineteen-early twentieth century at caused some probmens,which means tradition was never broken before

3. Gulfem had right to send concubine to Suleiman and even reject one already chosen.

4. Suleiman had no known concubine that time

5. Gulfem was not building anything as all of her projects was already finished.

6. Even if she was building something, it would cost so much mere concubine would never have enough money to help it. Gulfem's daily stipend was 150 akches, which is almost four times as much as Mahidevran's and almost as much as imperial princesses', while titles concubines were receiving 1-6 depending on their status.

7. Even if she needed something she would ask it to either Suleiman, Mihrimah or Sah huban as we know it had happened before and they thought her as family member.

8. Even if we just jump these 7 reasons and somehow accept that Suleiman realy called her that night , he would never kill her for that, she broke no rule, she needed money for project, he would understand this.

9. Gulfem was childhood friend of Suleiman, she was already a high ranking woman when mahidevran came,so she was certainly older than her,who was likely born in 1498-99, she was even older than Suleiman most likely. She was a childhood friend of one of Suleiman's sisters so her date of birth could vary from 1490 to 1493. That would make her between 69 and 72 in 1562. Dieing at such age is nothing strange even today, live past 60 was actually achievement in her era. There is no need to look for intrigue where there is none. Several theory existed,but show chose most dramatic one,that happened to be least likely.

8. Safiye's arrival

I have nothing against the portrayal of her origin, but about how she got in Murad's harem. Accord- ing to MC she was Mihrimah's gift. However,in real life she was raised and educated at Humaşah sultan's court,who later gifted Sifiye(then called Meleki) to her cousin.

9. History of Kösem

In Magnificent Century Kosem young Anastasia was kidnapped as a gift of Safiye to Ahmed per his accession. Actually, Kösem, then called Mahpeyker, was a servant of Handan Sultan and met Ahmed in his mother's personal Gardens. Ahmed developed a "Childhood crush" towards her and Handan,aware of what it could cause, had Kösem beaten up and exiled. When Ahmed ascended her recalled her and brought back.

10. Another forgotten child.

In the show, Şehzade Mehmed died without any kids, while in reality, he had a posthumous daughter born in 1543 named Humaşah. Who grew up to be one of the most powerful women in the Ottoman empire. She was one of two favourite grandchildren of Suleiman and Hurrem and due to the death of her father, she was raised in the household of her grandmother, so she would have been deeply involved in their later life. However, her existence was completely cut out, while the role and importance of Ayse Humaşah, daughter of Mihrimah Sultan was reduced into nothingness.

#history#16th century#historical drama#magnificent century#magnificent century kosem#mc: kosem#medieval women#hurrem sultan#kosem sultan#safiye sultan#nurbanu sultan#gulfem hatun#sultan suleyman#ottomanladies#ottoman history#ottoman#ottoman empire#ottoman sultanas#historical figures#historical events#haseki hurrem sultan#ayse sultan#valide sultan#historical fiction

130 notes

·

View notes

Video

New archeological find confirms and supports historical theory!

92 notes

·

View notes

Text

If you get an opportunity to go through the British Library digitised manuscripts, don’t miss this one! So many hilarious and bizarre images!

Harley MS 6563

Date c. 1320-c. 1330

Title: Book of Hours (fragmentary)

httpss://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?index=4&ref=Harley_MS_6563

Here were my favourites:

1. I love her sassy face. They believe she represents the sin of avarice.

2. Woman playing the tambourine

3. Woman fighting with distaff

4. Woman fighting with sword

5 & 6. Nude warriors

7. Woman grieving at a tomb

8 & 9. Medieval killer bunnies, because they make me happy.

266 notes

·

View notes

Text

So here's one of the coolest things that has happened to me as a Tolkien nut and an amateur medievalist. It's also impacted my view of the way Tolkien writes women.

Here's Carl Stephenson in MEDIEVAL FEUDALISM, explaining the roots of the ceremony of knighthood:

"In the second century after Christ the Roman historian Tacitus wrote an essay which he called Germania, and which has remained justly famous. He declares that the Germans, though divided into numerous tribes, constitute a single people characterised by common traits and a common mode of life. The typical German is a warrior. [...] Except when armed, they perform no business, either private or public. But it is not their custom that any one should assume arms without the formal approval of the tribe. Before the assembly the youth receives a shield and spear from his father, some other relative, or one of the chief men, and this gift corresponds to the toga virilis among the Romans--making him a citizen rather than a member of a household" (pp 2-3).

Got it?

Remember how Tolkien was a medievalist who based his Rohirrim on Anglo-Saxon England, which came from those Germanic tribes Tacitus was talking about?

Stephenson argues that the customs described by Tacitus continued into the early middle ages eventually giving rise to the medieval feudal system. One of these customs was the gift of arms, which transformed into the ceremony of knighthood:

"Tacitus, it will be remembered, describes the ancient German custom by which a youth was presented with a shield and a spear to mark his attainment of man's estate. What seems to the be same ceremony reappears under the Carolingians. In 791, we are told, Charlemagne caused Prince Louis to be girded with a sword in celebration of his adolescence; and forty-seven years later Louis in turn decorated his fifteen-year-old son Charles "with the arms of manhood, i.e., a sword." Here, obviously, we may see the origin of the later adoubement, which long remained a formal investiture with arms, or with some one of them as a symbol. Thus the Bayeux Tapestry represents the knighting of Earl Harold by William of Normandy under the legend: Hic Willelmus dedit Haroldo arma (Here William gave arms to Harold). [...] Scores of other examples are to be found in the French chronicles and chansons de geste, which, despite much variation of detail, agree on the essentials. And whatever the derivation of the words, the English expression "dubbing to knighthood" must have been closely related to the French adoubement" (pp 47-48.)

In its simplest form, according to Stephenson, the ceremony of knighthood included "at most the presentation of a sword, a few words of admonition, and the accolade."

OK. So what does this have to do with Tolkien and his women? AHAHAHAHA I AM SO GLAD YOU ASKED. First of all, let's agree that Tolkien, a medievalist, undoubtedly was aware of all the above. Second, turn with me in your copy of The Lord of the Rings to chapter 6 of The Two Towers, "The King of the Golden Hall", when Theoden and his councillors agree that Eowyn should lead the people while the men are away at war. (This, of course, was something that medieval noblewomen regularly did: one small example is an 1178 letter from a Hospitaller knight serving in the Latin kingdom of Jerusalem which records that before marching out to the battle of Montgisard, "We put the defence of the Tower of David and the whole city in the hands of our women".) But in The Lord of the Rings, there's a little ceremony.

"'Let her be as lord to the Eorlingas, while we are gone.'

'It shall be so,' said Theoden. 'Let the heralds announce to the folk that the Lady Eowyn will lead them!'

Then the king sat upon a seat before his doors and Eowyn knelt before him and received from him a sword and a fair corselet."

I YELLED when I realised what I was reading right there. You see, the king doesn't just have the heralds announce that Eowyn is in charge. He gives her weapons.

Theoden makes Eowyn a knight of the Riddermark.

Not only that, but I think this is a huge deal for several reasons. That is, Tolkien knew what he was doing here.

From my reading in medieval history, I'm aware of women choosing to fight and bear arms, as well as becoming military leaders while the men are away at some war or as prisoners. What I haven't seen is women actually receiving knighthood. Anyone could fight as a knight if they could afford the (very pricy) horse and armour, and anyone could lead a nation as long as they were accepted by the leaders. But you just don't see women getting knighted like this.

Tolkien therefore chose to write a medieval-coded society, Rohan, where women arguably had greater equality with men than they did in actual medieval societies.

I think that should tell us something about who Tolkien was as a person and how he viewed women - perhaps he didn't write them with equal parity to men (there are undeniably more prominent male characters in The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit, at least, than female) but compared to the medieval societies that were his life's work, and arguably even compared to the society he lived in, he was remarkably egalitarian.

I think it should also tell us something about the craft of writing fantasy.

No, you don't have to include gut wrenching misogyny and violence against women in order to write "realistic" medieval-inspired fantasy.

Tolkien's fantasy worlds are DEEPLY informed by medieval history to an extent most laypeople will never fully appreciate. The attitudes, the language, the ABSOLUTELY FLAWLESS use of medieval military tactics...heck, even just the way that people travel long distances on foot...all of it is brilliantly medieval.

The fact that Theoden bestows arms on Eowyn is just one tiny detail that is deeply rooted in medieval history. Even though he's giving those arms to a woman in a fantasy land full of elves and hobbits and wizards, it's still a wonderfully historically accurate detail.

Of course, I've ranted before about how misogyny and sexism wasn't actually as bad in medieval times as a lot of people today think. But from the way SOME fantasy authors talk, you'd think that historical accuracy will disappear in a puff of smoke if every woman in the dragon-infested fantasy land isn't being traumatised on the regular.

Tolkien did better. Be like Tolkien.

#tolkien#middle earth#jrr tolkien#lord of the rings#lotr#the lord of the rings#eowyn#writing fantasy#fantasy#female characters#writing#historical fiction#medieval women#medieval history#medieval#history#womens history

8K notes

·

View notes

Text

The relatively scant discussion of arms and hands landed medieval writers somewhere that our own society (and certainly the legions of evolutionary psychologists) likes to place emphasis—the breasts. If you as a modern reader are excitedly hoping for tales of heaving bosoms spilling from gowns, I am afraid I have disappointing news for you. Medieval men were uniform in their description of the perfect set of boobs as decidedly small and white. Matthew of Vendôme praised the "dainty" breasts of Helen of Troy, which lay "modest on her chest." Geoffrey of Vinsauf meanwhile wrote that the ideal beauty's breasts were like gems and were only a "brief handful." Machaut, adding more adjectives to the discussion of a young woman's chest, nonetheless took pains to emphasize that while they were "white, firm, and high-seated/pointed, round," they were also "small enough," perhaps indicating that in an ideal world her cups would overflow a bit less.

An interest in small breasts is of note because this ideal too was easier for the wealthy to live up to, as they could opt out of breast-feeding. Most mothers undoubtedly nursed their own children, but wealthy women could employ wet nurses to do so in their stead. Women of the nobility and royalty simply bound their maternal breasts up, to ensure that they shrank back down to a pleasing size, and left it to the lower-class women in their employ to feed any and all screaming mouths. The wet nurse as the preferred method of keeping breasts small is testified to in the Trotula, a twelfth-century medical guidebook, in a segment called “On Conditions of Women,” which devotes an entire section to "Choosing a Wet Nurse." Funnily, any good wet nurse should have the preferred beauty attributes found among the nobility, "redness mixed with white . . . who is not blemished, nor who has breasts that are flabby or too large . . . and who is a little bit fat." In this way, well-off women had the ability to keep the dainty breasts that were so preferred, while also ensuring the beauty benefits of a good night's sleep.

-Eleanor Janega, The Once and Future Sex: Going Medieval on Women’s Roles in Society

#eleanor janega#medieval women#female breast in history#breastfeeding in history#womens history#classism#the more things change the more they stay the same

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

"That Æthelswith was the bestower of such gifts is consistent with the other things we know about her. In 868 she witnessed a West-Saxon charter, in which she made a grant of fifteen hides of her own land in Berkshire. She also witnessed all of her husband King Burgred’s charters. Though we only see glimpses of her influence, Æthelswith, like other Mercian queens before her, was a politician.

In 874, twenty one years after Æthelswith married Burgred, the royal couple were forced out of their kingdom by an encroaching Viking army. They fled together to safety in Rome. While Burgred died soon after they arrived, Æthelswith outlived him for another decade, which she spent in Italy.

Queen Æthelswith passed away in 888 in Pavia, and was laid to rest there. She may have been undertaking a pilgrimage when she died. Her body and the ring that she once bestowed were both buried underground a thousand miles apart. And they say medieval women didn’t travel…"

#Æthelswith#history#women in history#women's history#9th century#english history#queens#leaders#english queens#anglo saxon history#anglo saxon england#medieval women#medieval history#middle ages#medieval#archeology

249 notes

·

View notes

Text

Women will see these images and be like "hell yeah"

#ora parlo io 🥶#radical feminists do touch#radical feminists please interact#radical feminism#women's history month#Women's history#medieval women#Medieval

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

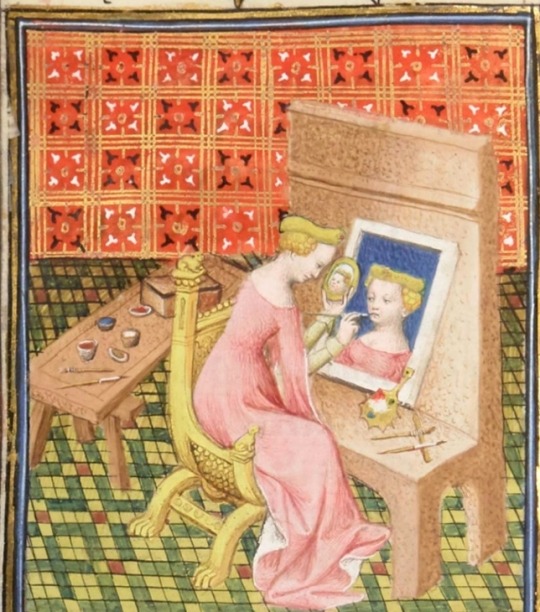

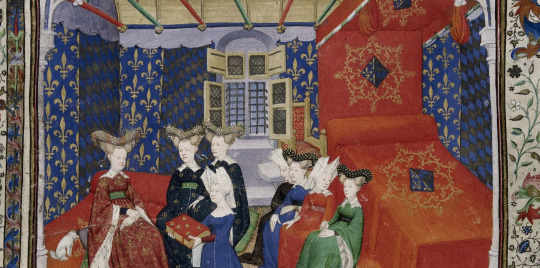

Educating the princesses

“All of these princesses, both foreign and French, had received a first-rate education. Some were raised at the French court from childhood, such as Philip IV’s wife Joan of Navarre and Charles VIII’s young fiancée Margaret of Austria. Others were educated within their own families in their respective principalities.

Educators had long debated what women should be taught. In 1265,

Philip of Novara had advised against teaching girls—except for nuns— how to read and write. He was, however, in the minority. Far from being neglected when it came to aristocratic education, women were the recipients of veritable miroirs aux princesses (didactic works presenting the exemplary image of the good ruler or, for women, the ideal princess), which reveal all the care that went into their training—as religious as it was moral and intellectual.

(...)

Beyond these theoretical treatises, sources on the practice of that time provide information about the educational methods of the period. Young princesses learned to read and often write. Such instruction often took place within the palace under a tutor. At the court of Savoy in the mid-fifteenth century, Pierre Aronchel was the schoolmaster of Louis and Anne of Cypress’s eldest daughters Margaret and Charlotte (future wife of Louis XI).

Like their brothers, young princesses first learned reading and religion. They learned to read using an alphabet book (Margaret of Austria learned the alphabet using a book handsomely bound in black velvet) and continued with psalters and books of hours. At the age of seven, young Joan of France, who was married to the Count of Montfort, received a richly illuminated book of hours of Notre-Dame from her mother Isabeau of Bavaria. During the fourteenth century, young girls at the court of Savoy practiced reading using liturgical collections, matins and penitential psalms, which were replaced by books of hours in the fifteenth century. Like their brothers, Savoyard princesses also learned to write.

Latin, however, was reserved for boys, which was one of the primary differences when it came to education. Princesses only knew the necessary prayers and formulas for following mass and reading their books of hours. There were a few exceptions nonetheless. Saint Louis’s sister Isabella of France (d. 1270), for example, was reputedly an excellent Latinist.

Failing Latin, aristocratic ladies knew other languages. John II’s future wife Bonne of Luxembourg, who had been raised in Bohemia, spoke Czech, German and French. Yolanda of Bar —daughter of Robert, Duke of Bar, and wife of John I, King of Aragon—could read ‘Limousin’ and Latin in addition to being able to write in French and Catalan. Others had a harder time learning a foreign language. During her entry ceremony in Paris in 1389, Isabeau of Bavaria was criticized for her poor understanding of French—four years after she had arrived in the kingdom.”

Queenship in medieval france 1300-1500, Murielle Gaude-Ferragu

#history#women in history#women's history#queens#middle ages#medieval women#france#french history#medieval history#isabeau of bavaria#Joan of navarre

95 notes

·

View notes