#minimalism materialism consumerism christianity

Text

Pursuing Minimalism: 5 Lessons Learned

The decision to pursue a minimalist lifestyle became easy the moment I decided I could no longer bear the burden of attachment to material possessions - but I first had to realize that such a burden even existed. Although we are still early in our journey and have much to learn, I am amazed at the depth of self-discovery that has already occurred only a few days in. It’s as if all of this has been teeming just beneath the surface, waiting for the right moment to present itself before bursting forth like a fountain, unannounced and unstoppable. (What better time than only days before a comprehensive respiratory final exam.) I am certain there will be more than 5 lessons to come of this adventure, but these first 5 have been so important that I couldn’t risk waiting to write them down later. Here goes nothing:

1. Having more than I need might actually be a bad thing.

I have assumed for most of my life that having an excess of things fell somewhere between good and neutral, that you could certainly stand to benefit from having extra things but at worst it would have neither positive nor negative affect on your life. After significant reflection, I now think very differently. My thoughts are summarized as follows.

By having more than we needed, we allowed ourselves a false sense of security, thinking that having multiples of the same or similar things made us "prepared". All it really made us was unable to properly use any of the things we owned. Often this was because we had so many things, we forgot that we even owned some of them. They were simply collecting dust in the deepest recesses of our cupboards and drawers, taking up space and not contributing to our lives, often resulting in us buying a duplicate of something without even realizing it.

While this might be fairly harmless on its own, the reasons behind our "need" for excess were not.

Speaking for myself, I was motivated to keep certain things I didn't need out of fear and uncertainty, essentially enslaving myself to preparing for a future I wasn't even sure I would have, never living in the present. When I first decided to let go of those "just-in-case" possessions, I found myself face to face with a fear of the unknown that I didn't even realize I had, and the freedom that followed it’s absence.

I was motivated to keep other things out of guilt, as they had been gifts or something I had spent a great deal of money on, regardless of its usefulness or its ability to offer anything of lasting value to my life. Most of these things were packed away in boxes, following me from apartment to apartment never to be unpacked, simply taking up space and quietly causing me anxiety every time I was reminded of their existence. Finally letting some of these things go lifted a burden I did not realize I had been carrying until I finally set it down.

For other things, I was motivated to keep them in order to maintain some sort of status or reputation, enslaving myself to the approval of others. As soon as I decided such status was no longer important to me, about half of my possessions suddenly lost their value.

Still for other things, I simply couldn't part with them because of their sentimental value. I had convinced myself that giving up this object would mean giving up my memories of loved ones, when in fact there is nothing that can take those memories from me, object or no object. I ended up choosing to keep a small amount of such sentimental items - mostly books and toys from my childhood that I hope to give to my children someday - and the rest I made peace with and said goodbye.

The anxiety and emotion that accompanied the simple task of throwing away an old pair of shoes or and unused gift was enough to grab my attention. This is a problem, and it needs to be addressed.

2. Having less things means making less decisions about them.

Having 4 professional outfits to choose from instead of 24 means less time spent every morning deciding what to wear to work.

Having less dishes to use means actually washing them as you use them instead of simply grabbing another dish and letting them pile up in your sink.

Having less bottles of hair product on your shelf means less time fumbling through everything trying to find the only one you ever use anyways.

Having 2 musical instruments in the house instead of 5 means I'll spend less time worrying about which one I should practice (or spend so much time trying to decide that I give up all together and play none of them).

Having less stuff means I'm actually excited to use the few things I do have because I know that they bring value to my life. For the first time in my life, I honestly believe that less is more.

3. For a family of 2, we produce an impressive (embarrassing) amount of garbage.

In these few days of intense purging, we have walked at least 8-10 bags of un-recyclable trash out to our dumpster - not to mention the 8-10 bags worth of stuff still sitting on our living room floor waiting to find a home with either our friends and family or at Good Will.

Even before we began this process, we've struggled to keep up with recycling. We know that it is important, but since our apartment doesn't offer it, and we don't know where to go, (and it's one more thing for us to try to squeeze into our already overloaded schedules) it simply hasn't been a priority for us to figure it out outside of occasionally taking our returnables back to Meijer. But it's time to make a change.

Our stewardship of the earth as followers of Christ is supposed to be an important task, gifted to humans above all other creatures because we were made in the image of its Creator. Unfortunately, most of us simply choose not to treat the earth this way, as something that was entrusted to us but does not truly belong to us. In light of this conviction, I plan to start asking myself with EVERY purchase and waste-related decision, "Would a proper steward of the earth make this same choice?"

As overwhelming as this will feel at first, making small changes every month will go a long way towards forming habits that will better honor God and the earth he has placed in our care.

4. An impressive (and embarrassing) proportion of my belongings are the result of an impulse purchase.

After some thorough self-reflection, I realized that, for most of my life, shopping has been an outlet for my anxiety. Whether I took an unsupervised trip down the snack aisle after a bad day or hit up the clearance rack in the women's clothing section, purchasing things brought me a fleeting happiness and momentary distraction from my stress - bordering on an addiction. I'd find all sorts of ways to justify my decisions - "It's on sale", "I really want it", or my favorite "I deserve this". And for the number of times I did it you'd think I'd have remembered the "fleeting" part and found some other more permanent solution, but for whatever reason I knowingly continued to pursue an empty well.

What hasn't been fleeting is the relief and freedom I have consistently found in giving my things away to others. Where my purchases added to the clutter that ultimately worsened my anxiety, giving them away removed the clutter and my anxiety followed suit.

Taking intentional steps to significantly reduce our number of possessions has done more for my mental health than just about anything else I've tried. I wish I could succinctly describe the peace (and weirdly the thrill) I have found in letting go of things I thought I'd keep indefinitely, and the spiritual parallels I am discovering as my walk with Christ is also "decluttered".

5. This shift in focus is not a phase, but rather something that has been quietly stirring, not making itself fully known until now.

Elements of minimalism have been making their way into my life ever since I gave my life to Christ 7 years ago. The story of the rich man has always been a convicting read, hearing about a young man who was so attached to and in love with his material possessions that he was unwilling to part ways with them in order to follow Jesus, Himself being the greatest gift mankind would ever receive. Easier it is for the camel to pass through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the kingdom of Heaven, Jesus said - not because God loves the rich young man any less than the next guy, but because the young man loved his stuff more than he loved God. His bondage to his valued possessions blinded him to the surpassing worth found in knowing Jesus. He allowed the temporary to take precedence over the eternal.

I do not think this passage of scripture implies that owning material possessions is evil. Owning things is a necessary fact of life on earth. But enslaving ourselves to them is not. And the more we own, the more we commit ourselves to a given standard of living, the more we stand to lose - and the harder it is to let it go.

Taking these teachings to heart requires asking ourselves some hard questions, and the end result will look differently for different people, but I can tell you that it has been one of the most rewarding and important things I have ever done. Might I challenge you, reader, to ask yourself the same thing: Where is your treasure?

0 notes

Text

Christmas Wasn't Always the Kid-Friendly Gift Extravaganza We Know Today

https://sciencespies.com/history/christmas-wasnt-always-the-kid-friendly-gift-extravaganza-we-know-today/

Christmas Wasn't Always the Kid-Friendly Gift Extravaganza We Know Today

There’s a special, even magical connection between children and the “most wonderful time of the year.” Their excitement, their belief, the joy they bring others have all become wrapped up in the Christmas spirit. Take the lyrics of classic songs like “It’s Beginning to Look a Lot Like Christmas,” “White Christmas,” or even the aptly titled “Christmas Is for Children” by country music legend Glen Campbell—these are just a few of the many pop culture offerings that cement the relationship between kids and Christmas. But it hasn’t always been this way, even though the holiday celebrates the Christ child’s birth. How kids got to the heart of Christmas has a lot to tell us about the hopes and needs of the modern grown-ups who put them there.

Until the late 18th century, Christmas was a boisterous affair, with roots in the pre-Christian Midwinter and Roman Saturnalia holidays. You’d find more along the lines of drunkenness, debauchery and raucous carousing at this time of year, especially from young men and the underclasses, than “silent night, holy night.” For example, in early forms of wassailing (the forerunner of neighborhood carol-singing) the poor could go into the homes of the rich, demanding the best to drink and eat in exchange for their goodwill. (Once you know this, you’ll never hear “Now bring us some figgy pudding” the same way again!)

But the boozy rowdiness of the season, together with its pagan roots, was so threatening to religious and political authorities that Christmas was discouraged and even banned in the 17th and 18th centuries. (These bans included the parliamentarians in mid-17th century England, and the Puritans in America’s New England in the 1620s—the “pilgrims” of Thanksgiving fame.) But then, as now, many ordinary people loved the holiday, making Christmas difficult to stamp out. So how did it transform from a period of misrule and mischief into the domestic, socially manageable and economically profitable season that we know today? This is where the children come in.

Until the late 18th century, the Western world saw children as bearers of natural sinfulness that needed to be disciplined toward goodness. But as Romantic ideals about childhood innocence took hold, children (specifically, white children) became seen as the precious, innocent keepers of enchantment that we recognize today, understood as deserving protection and living through a distinct phase of life.

This is also the time when Christmas began to transform in ways that churches and governments found more acceptable, into a family-centered holiday. We can see this in the peaceful, child-focused carols that emerged in the 19th century, like “Silent Night,” “What Child Is This?,” and “Away in a Manger.” But all the previous energy and excess of the season didn’t just disappear. Instead, where once it brought together rich and poor, dominant and dependent according to old feudal organizations of power, new traditions shifted the focus of yuletide generosity from the local underclasses to one’s own children.

Meanwhile, the newly accepted “magic” of childhood meant that a child-centered Christmas could echo the old holiday’s topsy-turvy logic while also serving the new industrializing economy. By making one’s own children the focus of the holiday, the seasonal reversal becomes less nakedly about social power (with the poor making demands on the rich) and more about allowing adults to take a childlike break from the rationalism, cynicism and workaday economy of the rest of the year.

Social anthropologist Adam Kuper describes how the modern Christmas “constructs an alternate reality,” beginning with rearranged social relations at work in the run-up to the holiday (think office parties, secret Santas, toy drives and more) and culminating in a complete shift to the celebrating home, made sacred with decked halls, indulgent treats and loved ones gathered together. During this season, adults can psychologically share in the enchanted spaces we now associate with childhood, and carry the fruits of that experience back to the grind of everyday life when it starts up again after the New Year.

This temporary opportunity for adults to immerse themselves in the un-modern pleasures of enchantment, nostalgia for the past and unproductive enjoyment is why it’s so important that kids fully participate in the magic of Christmas. The Western understanding of childhood today expects young people to hold open spaces of magical potential for adults through their literature, media, and beliefs. This shared assumption is evident in the explosion of children’s fantasy set in medieval-looking worlds over past century, which was the focus of my recent book, Re-Enchanted (where I discuss Narnia, Middle-earth, Harry Potter and more). Christmas or Yule appear in many of these modern fairy stories, and sometimes even play a central role—think Father Christmas gifting the Pevensie children weapons in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe—using the holiday as a bridge between the magical otherworlds of fiction and our real-world season of possibility.

Beyond storytelling, we also literally encourage kids to believe in magic at Christmas. One of the most iconic expressions this is an 1897 editorial in the New York Sun titled “Is There a Santa Claus?” In it, editor Francis Pharcellus Church replies to a letter from 8-year-old Virgina O’Hanlon with the now-famous phrase “Yes, Virginia, there is a Santa Claus,” and describes her friends’ disbelief as coming from the “skepticism of a skeptical age.” Church argues that Santa “exists as certainly as love and generosity and devotion exist,” minimizing the methods of scientific inquiry to claim that “[t]he most real things in the world are those that neither children nor men can see.”

Many of the arguments for the importance of the arts and humanities that we still hear today can be found in Church’s language, which identifies sources of emotional experience like “faith, fancy, poetry, love, romance”—and belief in Santa Claus—as crucial to a humane and fully lived life. According to this mindset, Santa not only exists, but belongs to the only “real and abiding” thing in “all this world.” “Yes, Virginia, there is a Santa Claus,” as it has come to be known, has been reprinted and adapted across media forms since its publication, including as part of holiday TV specials and as the inspiration for Macy’s department store’s “Believe” charity and advertising campaign since 2008.

The fact that the sentiments in this editorial have come to be associated with a major retailer may seem ironic. Yet, calls to reject consumerism at Christmas have been around ever since it became a commercial extravaganza in the early 19th century, which is also when buying presents for kids became a key part of the holiday. How to explain this? Today, just as in premodern Christmases, overturning norms during this special time helps to strengthen those same norms for the rest of the year. The Santa myth not only gives kids a reason to profess the reassuring belief that magic is still out there in our disenchanted-looking world, it also transforms holiday purchases from expensive obligations into timeless symbols of love and enchantment. As historian Stephen Nissenbaum puts it, from the beginning of Santa Claus’s popularization, he “represented an old-fashioned Christmas, a ritual so old that it was, in essence, beyond history, and thus outside the commercial marketplace.” Kids’ joyful wonder at finding presents from Santa on Christmas morning does more than give adults a taste of magic, it also makes our lavish holiday spending feel worthwhile, connecting us to a deep, timeless past—all while fueling the yearly injection of funds into the modern economy.

Does knowing all this ruin the magic of Christmas? Cultural analysis doesn’t have to be a Scrooge-like activity. To the contrary, it gives us the tools to create a holiday more in line with our beliefs. I’ve always found the way we abandon kids to deal with the discovery that “Santa isn’t real” on their own—or even expect them to hide it, for fear of disappointing adults that want to get one more hit of secondhand enchantment—unethical and counter to the spirit of the season. The song “I Saw Mommy Kissing Santa Claus” is supposed to be funny, but it captures shades of the real anxiety many kids go through every year. Knowing what children and their belief do for society during the holidays can help us choose a better approach.

A couple of years ago I saw a suggestion floating around on the internet that I think offers an ideal solution for those who celebrate Christmas. When a child starts questioning the Santa myth and seems old enough to understand, take them aside and, with utmost seriousness, induct them into the big grown-up secret: Now THEY are Santa. Tell the child that they have the power to make wishes come true, to fill the world with magic for others, and as a result, for us all. Then help them pick a sibling or friend, or better yet, look outside the family circle to find a neighbor or person in need for whom they can secretly “be” Santa Claus, and let them discover the enchantment of bringing uncredited joy to someone else. As Francis Pharcellus Church wrote to Virginia O’Hanlon more than 100 years ago, the unseeable values of “love and generosity and devotion” are in some ways the “most real things in the world,” and that seems like something that all kids —whether they’re age 2 or 92—can believe in.

Maria Sachiko Cecire is an associate professor of literature and the director of the Center for Experimental Humanities at Bard College. This essay has been adapted from material published in her recent book, Re-Enchanted: The Rise of Children’s Fantasy Literature.

#History

0 notes

Text

Let’s Talk About Ethics: Worldviews, Justice, and Education

Environmental ethics and philosophy are a great portion of environmental studies. Science would have no significant call to action for humans if we didn’t have a sense of right and wrong.

There are a few basic environmental worldviews that inform individuals beliefs on environmental issues. Human-centered (anthropocentric) environmental worldviews are primarily concerned with the needs and desires of humans. One such view is called the planetary management worldview, which holds humans as the hierarchically highest species, giving them the ability to manage the Earth however they see fit for their own personal requirements; the value of other species comes from how valuable they are to humans. There are three major variations: the no-problem school, the free-market school, and the spaceship-earth school. The first believes that environmental issues are solved through economic, managetary, and technological improvements. The second holds that a free-market global economy is the best thing for the environment, with minimal interference from the government. The third, and perhaps most abstract, views the Earth as a spaceship, that is, it is a complex machine that we can control.

A second anthropocentric view is the stewardship worldview, which declares that humans have an ethical responsibility, or obligation (depending on the strength of the view), to take care of the Earth. Some find this foolish because they believe it’s not the Earth that needs saving, humans do.

Some dismiss these worldviews all together because they assume that we have the knowledge and power to be effective stewards of the Earth. As it is now, the way we are “managing” the Earth is only benefiting us, and not even in the long-term. There is no evidence to support the idea of us successfully managing the Earth. Critiques of the global free-market point out that “we cannot have an unlimited economic growth and consumption on a finite planet with ecological limits or boundaries” [1]. Finally, the spaceship concept may be interesting but is far too oversimplifying and misleading.

Life-centered, or earth-centered, worldviews expand the boundaries of what life forms should be valued beyond humans. The environmental wisdom worldview believes that we should study nature and use it to guide us in living more sustainably, that we are a part of the community of life that sustains us and all other species, and that we are not in charge of the world. Research shows that becoming more environmentally literate is an important factor in environmental change.

Figure 1. A Guide to Environmental Literacy. (Miller, G. Tyler. Living in the Environment. National Geographic Learning/Cengage Learning, 2018.)

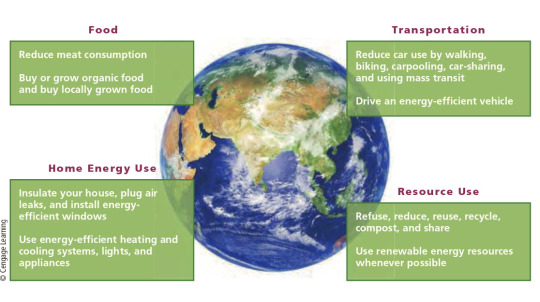

Research also shows, however, that education is not enough. We ought to foster a true ecological, aesthetic, and spiritual appreciation for nature, which happens primarily through experience in nature. Furthermore, an important factor in living more sustainably is consuming less. Not only does this benefit the environment, but it also combats the ethically questionable concepts of materialism and consumerism, and the idea that things can bring happiness. Research shows that people actually crave community, not stuff.

Figure 2. Ways to Live More Sustainably. (Miller, G. Tyler. Living in the Environment. National Geographic Learning/Cengage Learning, 2018, 693)

We also need to avoid two common views that lead to no effective change: gloom-and-doom pessimism and blind technological optimism. The first views the situation as too dire to combat, while the second puts too much hope in technology saving us without us putting in the work.

Environmental justice examines environmentalism through the lens of social justice. It recognizes that environmental issues aren’t purely natural, they are distributive, participatory, political, and cultural. It is an interdisciplinary field that combines humanities and hard sciences. In the U.S., the environmental justice movement rose as it became clear that “a disproportionate burden of environmental harms was falling on African Americans, Latino/a Americans, Native Americans, Asian Americans, the working class, and the poor” [2]. Beyond the U.S., environmental justice extends to issues of colonialism, the global environmental commons, and the effects of the corporate globalization.

I believe that a complete view of environmentalism must include environmental justice. Environmental issues are inherently linked to issues of wealth disparity, racism, and colonialism. Therefore, environmental solutions need to recognize the disproportionate effects of climate change in order to bring true, comprehensive change. For example, we must recognize that low-income communities and communities of color suffer more from being located near industrial plants or waste disposal sites than wealthier communities who have the resources to influence the location of those sites, or to choose to live elsewhere.

Intergenerational justice is the idea that current generations have obligations to past or future generations. Applied to environmentalism, it holds that those living now have a responsibility to preserve ecosystems and conserve resources for the next generations. While I think the idea of protecting Earth for future generations is not harmful in itself, I think it has the tendency to fall into anthropocentrism and therefore fails to address the issue comprehensively. Yet again, the focus is only on humans and not on the millions of other species that we are affecting through our environmental havoc. While it might be successful in inspiring care for the environment since it appeals to pride, it truly only reflects a care for ourselves, which I consider a failure.

Environmental citizenship is the idea that humans are a part of a larger ecosystem and that our future is dependent on each individual accepting the challenge and acting for change. Instead of human domination of the environment, humans are seen as members of the environment. It appeals to a sense of ethics similar to Aristotle’s virtue ethics. It internationalizes the concept of stewardship as it is more religiously neutral, and even clarifies the misunderstanding of human dominion for domination in Judeo-Christian traditions. While environmental citizenship is difficult to pin down, its general principle is helpful in educating and creating change due to its neutrality. Growing up in a primarily Christian community, I am far too familiar with the confusion of human dominion for human domination. I think that religiously neutral stances of environmentalism could be helpful in bringing about comprehensive and international change.

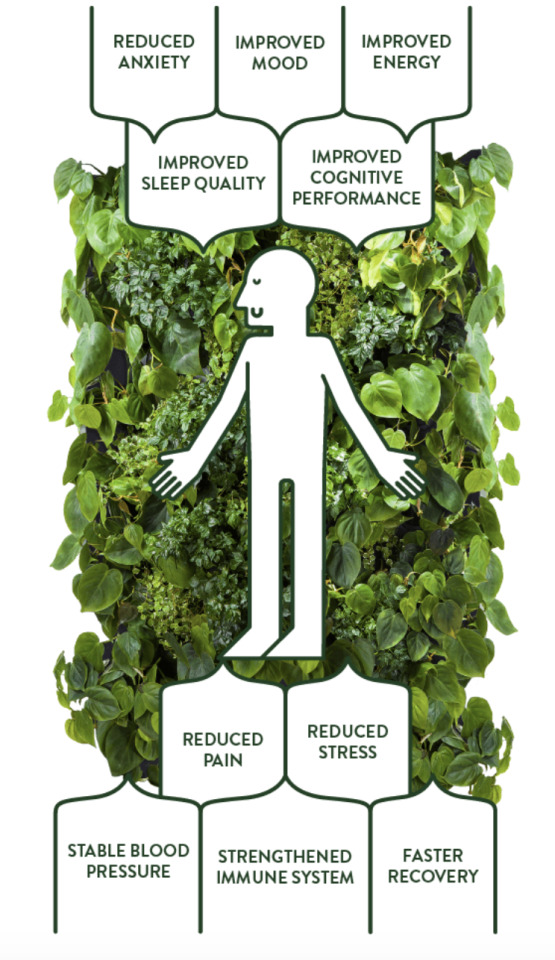

Another important idea is biophilia, an “innately emotional affiliation of human beings to other living organisms” [3]. There is research supporting the idea that the brain “has an evolved intelligence that grew out of the need for detailed information about nature” [4]. Nature also provides many benefits to human health and well-being, through direct contact, indirect contact, and simulations such as photographs. Windows, trees, and gardens are just a few elements of nature that have been shown to improve human behavior. However, it is also important to note how human attraction to nature has led to unsustainable practices, such as building hotels in the forest for panoramic views. Far too often our appreciation of nature is harmful to it.

Figure 3. How exposure to natural elements is known to improve health and well-being. (Heiskanen, Siru. “Biophilia - The Love of Life and All Living Systems.” NAAVA. September 11, 2017. Accessed February 17, 2020. https://www.naava.io/editorial/biophilia-love-of-life)

Last Child in the Woods is a book about emerging research that shows how important exposure to nature is for healthy childhood development. Author Richard Louv comments on today’s “nature-deficit disorder” in children which could have ties to the rising rates of obesity, attention disorders, and depression. The book began the No Child Left Inside movement, focused on creating increased interest in children’s environmental awareness. The movement has impacted legislation and been endorsed by 58 organizations. In Milwaukee, WI, Riverside Park was once a place of crime and pollution, but after the introduction of an outdoor-education program and removal of a dam, the park has been restored. As one puts it, “nature was not the problem; it was the solution” [5]. The movement brings people together through agreement on one basic principle: “no one among us wants to be a member of the last generation to pass on to our children the joy of playing outside in nature” [6].

Finally, with all of this research and talk of the importance of education comes an important disclaimer: education does not guarantee decency. In fact, a large portion of damage is done by highly educated individuals. All of that to say, it’s not only a matter of educating, but a matter of how we educate.

Word Count: 1309

Question: What system of environmental ethics is most successful in creating change? Does it differ person-to-person?

[1] Miller, G. Tyler. Living in the Environment. 19th ed. (Boston: Cengage Learning, 2018) 684.

[2] Figueroa, Robert Melchior. “Environmental Justice.” Encyclopedia of Environmental Ethics and Philosophy. 342. https://drive.google.com/file/d/0BzKbjVLpnX0RczhaLWFEMFJWbjg/view

[3] Heerwagen, Judith. “Biophilia.” Encyclopedia of Environmental Ethics and Philosophy. 109. https://drive.google.com/file/d/0BzKbjVLpnX0RQ2p3dlZ3UGlMNVk/view

[4] Heerwagen, 110.

[5] Louv, Richard. “Children and Nature Movement.” Richard Louv. 2008. http://richardlouv.com/books/last-child/children-nature-movement/

[6] Louv, 2008.

0 notes

Text

Silly Things Christians Say: ‘God Will Provide’

When it comes to preaching on money in the Church, we usually talk about being “good stewards” by getting out of debt and of course giving money to the Church. Of course, neither of these are bad, but I think there is one passage that is either ignored or quickly glossed over in most situations. In Matthew 6 we have a portion of the Sermon on the Mount where Jesus speaks his famous words:

Therefore I tell you, do not worry about your life, what you will eat or drink; or about your body, what you will wear. Is not life more than food, and the body more than clothes? Look at the birds of the air; they do not sow or reap or store away in barns, and yet your heavenly Father feeds them. Are you not much more valuable than they? Can any one of you by worrying add a single hour to your life?

And why do you worry about clothes? See how the flowers of the field grow. They do not labor or spin. Yet I tell you that not even Solomon in all his splendor was dressed like one of these. If that is how God clothes the grass of the field, which is here today and tomorrow is thrown into the fire, will he not much more clothe you—you of little faith? So do not worry, saying, ‘What shall we eat?’ or ‘What shall we drink?’ or ‘What shall we wear?’ For the pagans run after all these things, and your heavenly Father knows that you need them. But seek first his kingdom and his righteousness, and all these things will be given to you as well.

Therefore do not worry about tomorrow, for tomorrow will worry about itself. Each day has enough trouble of its own (Matthew 6:25-34).

Jesus is clear: do not worry about these things, because God has provided and will continue to do so.

So many of us love to stop right there, though, because that’s easy. Rather than letting these verses challenge our relationship to our consumption, we assume that the standard of living we have come to expect need not be changed. We walk away with a generic, shallow, and bland spiritual platitude that has no more depth than the Bob Marley song, “Don’t worry about a thing, cause every little thing is gonna be alright.”

When Jesus said not to worry about food or drink or clothes or even their lives, He was speaking to a crowd of people who literally had to worry about not having these things. I think many of us need to shift our focus from the command not to worry and the reassurance that God will provide and ask ourselves what it means for God to provide in the first place.

What does it mean that God will provide? To learn this, we may need to stop spending money on new clothes–many of which are made by laborers under abusive conditions–and start shopping at Goodwill. And that is God providing. We may need to forego spending a thousand dollars on the latest iPhone for the used hand-me-down that is three or four generations old. And that is God providing. Rather than a $12,000 car that’s 3 years old, we might have to buy one that’s $1,200 and 13 years old. And that is God providing. We might have to give up the 1500 square feet in St. John or Bedford for 500 in Lansing or Manchester. (I’ve lived in New Hampshire and Illinois, but feel free to substitute your own “rich” and “poor” towns). And that is God providing. We can even come to know God’s provision when we have to go to the food pantry to make ends meet.

We might need to do all of this because we can’t afford better. However, we might not need to do any of it, because we have more than enough to live the life we want. But in another very real sense, we can and must choose to make decisions like these to be able to be generous with our funds in the service of God. Because if we are to be part of the Church, we must be generous; and it is not truly the kind of generosity God desires unless it costs you something.

Generosity over Greed

When we handle our money the way Jesus taught, we do not only witness to God’s provision; we also witness to His generosity. The point of the radically counter-cultural teachings on possessions that we find in the New Testament is not asceticism–denying oneself pleasure and earthly goods to earn God’s favor or because they are inherently bad. Rather, it is to free us from the hold that these things have on our lives and empower us to be no longer self-centered, but others-centered when it comes to the way we use our resources. Martin Luther defined “sin” as a soul incurvatus in se–curved in on itself. Well, I think a sinful handling of money looks like a wallet curved in on itself.

Jesus is calling us to have our bank statements be as much of a witness to the Kingdom as our sermons. In many ways, our spending can preach louder than our words as we literally put our money where our mouth is.

The fact is that “God will provide” often means “God will provide through us.” Using the examples above, you might have enough money to provide all of those things–but what if you chose to shop at Goodwill to give some nice clothes to others? Or if you chose to go to the food pantry to give another family grocery money? Or if you’ve already got the nice house, what if you shared a spare room for free with a person in need?

I have found that the very best way to witness to God’s provision (and to rethink what that means altogether) and cooperate with God’s generous heart is by reorienting my view on possessions to become more and more of a minimalist.

Minimalism over Extravagance

Minimalism–the “new” hipster trend. The commitment to reducing the number of possessions to live the most simple and full life possible has gained a lot of momentum recently. The most recognizable faces of this movement are Josh Millburn and Ryan Nicodemus, “The Minimalists.” Their documentary, book and podcast have taken on American consumerism and materialistic greed and, against all odds, scored a major victory.

When I first saw their film Minimalism: A Documentary, I was surprised that so many of the converts to this movement came not from poor backgrounds in which they had to struggle to make ends meet, but from wealthy–sometimes extravagantly wealthy–situations. I thought Minimalism would be about a way to live life fully with a shortage of income, yet so many of the interviews were with people who had stories similar to Josh and Ryan, who write, “Nearly a decade ago, while approaching age 30, we had achieved everything that was supposed to make us happy: six-figure careers, luxury cars, oversized houses, and all the stuff to clutter every corner of our consumer-driven lives.” Yet, in spite of all this, they found themselves left with “a lingering discontent.”

This discontent with all the fittings of the American Dream was the one common thread that ran through every single interview. It’s actually the one thing that stood out to me most about the film. The Minimalists continue, “And yet with all that stuff, we weren’t satisfied. There was a gaping void, and working 80 hours a week just to buy more stuff didn’t fill the void. It only brought more debt, stress, anxiety, fear, loneliness, guilt, overwhelm, depression.”

The dramatic and revolutionary idea of minimalism is to make a total priorities pivot regarding our view of “stuff.” The Minimalists explain it well,

At first glance, people might think the point of minimalism is only to get rid of material possessions. But that’s a mistake. True, removing the excess is an important part of the recipe—but it’s just one ingredient. If we’re concerned solely with the stuff, though, we’re missing the larger point.

Minimalists don’t focus on having less. We focus on making room for more: more time, more passion, more creativity, more experiences, more contribution, more contentment, more freedom. Clearing the clutter from life’s path helps make that room.

Minimalism is the thing that gets us past the things so we can make room for life’s important things—which aren’t things at all.

How is it that so many people who do not consider themselves part of the Church are taking hold of this truth while so many evangelicals in the United States are still playing by the worn out rules of consumerism? How are people “in the world” coming closer to the heart of Jesus’ teachings on money and possessions while many Christians here are still literally buying into the view that more wealth and material comforts are always God’s blessings? (Maybe we need to rethink our assumption that the world is “ignorant” to God’s built-in patterns of the universe.)

Christian Minimalism versus “Secular” Minimalism

But there is one major difference between Christian minimalism and secular minimalism: Christian minimalism is both a crucial witness to the Kingdom of God and a profoundly transformative spiritual practice. How is reducing possessions and financial entanglements a spiritual practice? Because “where your treasure is,” Jesus said, “your heart will be also.” (Matthew 6:22) I would even go so far as to say that this commitment is more spiritually (trans)formative than daily Bible reading or quiet times–since it is actually living out Scripture.

Secular minimalism is about pivoting our priorities to reduce clutter and stress, to live our fullest life, and to “make room for more.” Christian minimalism embraces all of these, but redefines what they mean by centering our priority not on self, but on Christ, His Kingdom and His Body. Christian minimalism is about giving, “for it is in giving that we receive.” It is about sacrificially taking up the Cross, “for if you try to hang onto your life, you will lose it.” (Matthew 16:25, NLT)

Christian minimalism is not asceticism, which often looks like self-denial for its own sake, many times to earn God’s favor. Instead, in its fullest form it embraces the perspective of New Monastics like Shane Claiborne, whose book The Irresistible Revolution about his intentional community, The Simple Way, left a permanent impact on my faith when I read it at 16.

Shane lives in an intentional community in a poor part of Philadelphia. Some of them make their own clothes, they grow as much of their own food as possible, and they share a common purse, making money available so that there is enough to supply the needs for each one. They all contribute in various ways, and they are relentlessly committed to being a presence of peace among a community that so desperately needs it.

While Claiborne’s particular form of minimalism is beautiful and inspiring, it is also extreme. It can be easy to write off this man in baggy, hand-sewn shirts and pants with a bandana covering his dreadlocks as just an extremist. Indeed, Claiborne himself identifies as an extremist, citing Martin Luther King’s famous quote on being “extremists for love and justice.” It is ironic that his radically counter-cultural way of life has led him to become an internationally known and highly regarded speaker while simultaneously making it easier and easier to dismiss his way of life as unrealistic or even irresponsible.

But what do we mean when we say irresponsible? What are the cultural values and narratives we have embraced that make it so easy for us to marginalize the way of life that Claiborne and so many other monastics–new and old–have chosen? The truth is that this form of Christian minimalism reaches closer to the heart of the Gospel and the practices of the early Church in Acts than the gospel of prosperity, preservation and self-sufficiency that we all too often accept without any qualifications. What makes Christian minimalists like Claiborne “irresponsible” to us might say more about our own hearts than the heart of the Gospel of Jesus Christ.

Editor’s note: This piece originally ran on CoreyFarr.com. It was republished here with permission.

Go to the article

0 notes

Text

Ways to Make Better and More Sustainable Shopping Decisions

Do you like keeping up with trends? If you do, read on.

The 21st century saw the rise of consumerism to another level. Most of the products in the market nowadays would not last for several months, either because of poor quality or they go out of fashion. It gives consumers reasons to buy and discard easily. Latest trends dictate the ever-present need to keep up with what’s in, which is not generally a bad thing until it becomes rampant and out of control.

This cycle of buying and discarding does not only impact the social and economic aspects of one’s life. It also brings in huge environmental repercussions, with companies scrambling to meet demands without considering how it affects the world. Now more than ever, consumers should be aware of their purchasing habits and do more to improve product sustainability footprints, where every chain in the creation of the product has certain consequences. So, how do you make sure you are making better and more sustainable shopping decisions?

Doing Your Research

The move to ethical and sustainable shopping can only be realized if you are well-informed about the products you are using and buying. Do your part by conducting your own research. There are many traceable companies that give transparency on their production, from the harvesting of raw materials to transporting the finished products to your local stores. Traceability safeguards every person involved in the production of the products. In the case of clothing, you will be able to trace how your T-shirt was produced. Knowing where it came from, whose hands touched it, and whether they were well-compensated can put things into perspective.

Photo by Charles Etoroma

Making Use of Consumer Tools

Shopping for products with specific environmental and social is the number one consideration when it comes to sustainable purchasing. Make sure that you do your part as a consumer by checking if the products you’re buying meet the standards. Consumer tools like environmental labels can help you identify greener, healthier products. Look out for labels like ECOLOGO, Energy Star, EPEAT, Fair Trade, GREENGUARD, and many others.

Checking the Latest Statistics

Another way to put things into perspective is to know your numbers. Check the latest statistics on the CO2 emissions produced by the apparel and textile industry each year. How many trees are cut down to make cellulose fabrics? How many companies don’t know the origins of their raw materials? You’ll realize how bad it gets each year. Companies try to keep up with constant demand for new inexpensive clothes by exploiting third world countries and turning to safe labor. Keeping abreast with the latest statistics will inspire you even more to make sustainable shopping decisions.

Photo by Christian Fregnan

Choosing Quality over Quantity

It might sound like a no-brainer, but hoarding clothes and the latest gadgets do not really help. It only costs you more money and enables companies to have more reasons to keep up the race to the bottom. Instead of investing in several inexpensive clothes, for example, you can shop for high-quality clothes that you know will last for several years. That way, you are saving money in the long run and stemming the rampant consumerism tendencies.

Considering Second-hand Stores

It is no secret that many clothes go to waste each year as people keep up with the latest trends, discarding the old ones that go out of style and replacing them with the hottest fashion pieces. You can help minimize the waste and fashion footprint by opting for second-hand stores to hunt for your wardrobe update. They usually sell at a fraction of their original price – a win-win for all.

Photo by Ashim D’Silva

Learning When to Say Enough

Overconsumption is a vice. Learn to draw the line and stop buying more things than you need. Be creative with your choices and mix and match what you already have in your closet. Love what you already have. Aside from letting your personal style shine, this practice can free your budget to let you take on experienced-based hobbies like traveling.

Getting More from Your Clothes

Knowing what your clothes are made of will help you better take care of them, which in turn makes them last longer. Get more from your clothes by determining whether they are made of silk, cotton, polyester, etc. and care for them accordingly. It’s also helpful to learn how to sew and mend your clothes and minimize the need to easily replace them when they only lose a button.

It’s easy to take the complexity of producing many of the products and goods you enjoy for granted when you are far removed from their history and origin. By being aware of sustainable actions when it comes to your shopping decisions, you can do a lot to help planet earth and improve society. Remember, a simple step is already a great start.

#sustainability#susatainable fashion#conscious consumer#tips#clothes#clothing trends#savetheearth#fashion

0 notes

Text

Expert: (Image credit Banksy) The holiday period provides us with a unique opportunity to express the new awareness that must inform a less commercialised and more sharing-oriented world. Rather than spending all our time partaking in conspicuous consumption, why don’t we commemorate Christmas by organising massive gatherings for helping the poor and healing the environment? ***** At this time of year, our overconsuming lifestyles in the affluent Western world are impossible to ignore. Brightly-lit shops are bursting with festive foods and expensive indulgences, while seasonal songs play in the background of shopping malls to keep us spending the money we don’t have on things we don’t need to make impressions that don’t matter. The frenetic commercialism of Christmas on the high streets continues to escalate to inconceivable proportions. Despite all the warnings from climate scientists that ordinary Western lifestyles are destroying the planet, still we buy enough Christmas trees in the UK alone that could reach New York and back, if placed in a straight line. Enough card packaging is thrown away in this country that could cover Big Ben almost 260,000 times. Not to mention the 4,500 tonnes of tin foil, the 2 million turkeys, the 74 million mince pies and 5 million mounds of charred raisins (from rejected Christmas puddings) that are thrown away come early January. Mountains of e-waste from discarded electronic items – much of it bought as unwanted gifts and soon discarded – is projected to reach 10 million tonnes by 2020. Pause for a moment and try to picture the extent of that annual waste by the British populace. For if you combine our surplus produce with every Christian nation in Western Europe, North America and other over-industrialised regions, you have an appalling idea of the unnecessary ecological destruction that we collectively contribute to each year. Christmas is, after all, only an exaggerated illustration of the gross materialism that defines our everyday lives in a consumerist society. What is more difficult for us to contemplate, however, is how our profligate consumption habits also directly exacerbate levels of inequality worldwide. We know that the so-called developed world – roughly 16% of the global population – consumes a hugely disproportionate share of the earth’s resources, and is responsible for at least half of all greenhouse gas emissions. But behind such statistics lies a depressing reality, in which our artificial standards of living in the global North are dependent on the dire working conditions and impoverishment of millions of people throughout the global South. In spite of the spurious claims of trickle-down economics by the adherents of corporate globalisation, the number of people living on less than $5-a-day has increased by more than 1.1 billion since the 1980s. The vast majority of people who live in developing countries survive on less than $10-a-day; none of their families can remotely afford the wasteful and conspicuous consumption that we consider normal. Our personal complicity in this unsustainable global order is highly complex, of course, because we are all caught in a socioeconomic and cultural system that depends on ever-expanding consumerism for its survival. Everywhere, we are besieged with messages that encourage us to buy more stuff, as profit-driven businesses increasingly seek to meet our needs – either real or constructed – through interaction in the marketplace. Our consumption patterns are often tied to our sense of identity, our desire for belonging, our need for comfort, our self-esteem. So we are all the victims of an excessively commercialised culture, not only in a collective way through environmental harm and global warming, but also through the proximate psychological and emotional harm that in some way afflicts everyone. We experience that harm through the time-poverty of affluence; through all the pressures of living in an individualistic and market-dominated society; through all that we have lost due to the competitive work/consume treadmill – our freedom for leisure, our mental space, our community cohesion, our psychological health. There is also an inarticulable form of spiritual harm that arises from simply being part of this exploitative world order, in which our over-consuming lifestyles in the West are connected to the vast suffering and immiseration of people in poorer countries who we do not know, or care to know. Clearly it is the whole system that needs to go through a radical transformation – but how can that transformation be brought about, when we ourselves are the constituent parts that maintain the system in its currently destructive form? Over many decades, the basic problem and solution has been well articulated in a theoretical sense by progressive thinkers. Numerable reports cite the physics of planetary boundaries, demonstrating how we already require one and a half planets to support today’s consumption levels. Simply put, it is impossible to reconcile the twin challenges of ending poverty and achieving environmental sustainability, unless we also confront the huge imbalances in consumption patterns across the world, and fundamentally re-imagine the economy as something different that escapes the growth compulsion. Hence the resurgent focus on post-growth economics in a world of limits, recognising the importance of reducing the use of natural resources in high-income countries, so that poorer nations can sustainably grow their economies and rapidly meet the basic needs of their populations. Nowhere is the case for sharing the world’s resources more obvious or urgent, than in the question of how to achieve equity-based sustainable development or ‘one planet lifestyles’ for all. Yet our societies remain so far from embarking on this great transition, that the interrelated trends of commercialisation, inequality and environmental destruction continue to intensify year on year. What better example of double-standards and duplicity than the spectacle of French President Emmanuel Macron convening the ‘One Planet Summit’ this month to demonstrate international solidarity in addressing climate change, while at the same time governments were attending the resurrected World Trade Organisation talks in their continued attempts to turn the world into a corporate playground with minimal protections for the poor. These larger questions of global injustice and ecological imbalance may seem far removed from our daily lives, but everyone who participates in a modern consumerist society is conjointly responsible for perpetuating destruction and divisions on an international scale. Again, our frenzied spending around Thanksgiving and Christmas time is a salient case in point, exemplifying how our relentless mass consumption is directly propping up an extreme market-oriented economic system, and further preventing us all from embracing the radical transformations that will be required in the transition to a post-growth world. What, then, should we do? There are lots of answers from campaigners about how we can de-commercialise Christmas, like the buy nothing movement that advocates we ignore altogether the conditioned compulsion to purchase luxury goods, thus demonstrating our awareness of over-consumption and how it affects global disparities and the earth. At the least, we can practise ethical giving and support the work of activist groups and charitable organisations. For example, Christian Aid has released a witty video this year that entreats UK citizens to be aware of festive food waste in the context of global hunger, and donate £10 from Christmas food shopping – enough for a family in South Sudan to eat for a week. Actions like these may constitute a small step towards celebrating Christmas with awareness of the critical world situation, and the need for Westernised populations to live more lightly on the earth, while prioritising the needs of the less-privileged. If extended beyond the holiday season, hopefully that awareness may be translated into a mass movement that rejects the consumerist lifestyle altogether, instead voluntarily downshifting their lifestyles and meeting more of their needs in ways that bypass the mainstream economy. As proponents of the gift economy, the commons and collaborative consumption variously attest, this is the long-term antidote to mass consumerism. It means becoming co-creators of alternative economic systems in which we reinvest in our communities, shift our values towards quality of life and wellbeing, and embrace a new ethic of sufficiency. It means resisting the competitive economic pressures towards materialism and privatised modes of living, thereby releasing our time and energies for cooperative activities that promote communal production, co-owning and civic engagement. It means, in short, an expanded understanding of what it means to be human on this earth, in which we relearn how to participate in civic life and share resources at every level of society. The holiday period during Christmas actually provides us with a unique opportunity to express the new awareness that must inform a less commercialised and more sharing-oriented world. Rather than spending all our time partaking in conspicuous consumption that has nothing to do with the message of Christ, why don’t we organise local meetings or massive gatherings for helping the poor and healing the environment, both in our own countries and further abroad? Such an appeal to our goodwill and conscience is made in a seminal essay by Mohammed Mesbahi, titled Christmas, the System and I. He exhorts us to imagine what could be done if all the money we needlessly spend on festivities and unwanted gifts was collectively pooled, then redistributed to all those who urgently need it. Indeed imagine what could be achieved if people not only donate to charities at this time of year, but also unite in countless numbers on the streets for sharing and justice on behalf of the poorest members of the human family. If Jesus were walking among us today, writes Mesbahi, surely that is what He would call on us to do. For what cause can be of greater priority in this era of growing inequalities and planetary crisis, than the need to save the millions of people who continue to die from poverty-related causes each year? Perhaps that would be the first expression of the true meaning of Christmas in the twenty first century, when millions of people come together in constant demonstrations that call upon our governments to implement the principle of sharing into world affairs. http://clubof.info/

0 notes