#mongol empire

Text

A medieval painting of Godzilla at the battle of Liegnitz in 1241, between the Mongol horde and European Knights.

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

Steppe heavy cavalry but on a chicken horse 👀

She's here to conquer your heart and steal your girl~

#mongol#mongolish#how fantastic#caffe art#art#doodle#ink#tone#armor#chicken horse#mongol empire#I ended up getting lots of different things but I don't have the time to do enough research#that's why she's mongol-esque#swords#knights#medieval#I tried to make her very cool#but frankly nobody looks super cool on a chicken#their locomotion is hard to figure out too ;(

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Yurt front door - Khiva, 2022

#original photographers#photographers on tumblr#travel#uzbekistan#ancient architecture#yurt#ger#mongol culture#mongol empire#architecture#streetphoto color

141 notes

·

View notes

Text

Safe conduct pass stating that the bearer is under the protection of the Mongol Empire, Yuan Dynasty, 13th century

from The Metropolitan Museum of Art

824 notes

·

View notes

Text

Khutulun, Mongolian Princess Warrior

#digital art#anime#anime and manga#anime art#artists on tumblr#anime aesthetic#anime drawing#anime style#art#artwork#history#world history#history tag#mongolia#mongol empire#mongol history#genghis khan#khan#khutulun#digital art#digital illustration#digital drawing#digital painting#drawing#lineart#my art#art style#art tag#illustration#art on tumblr

173 notes

·

View notes

Text

They say a maiden carrying a lamb can travel the entire length of the Mongol Empire alone

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stone Turtle of Karakorum, Mongolia, c. 1235-1260 CE: this statue is one of the only surviving features of Karakorum, which was once the capital city of the Mongol Empire

The statue is decorated with a ceremonial scarf known as a khadag (or khata), which is part of a Buddhist custom that is also found in Tibet, Nepal, and Bhutan. The scarves are often left atop shrines and sacred artifacts as a way to express respect and/or reverence. In Mongolia, this tradition also contains elements of Tengrism/shamanism.

The city of Karakorum was originally established by Genghis Khan in 1220 CE, when it was used as a base for the Mongol invasion of China. It then became the capital of the Mongol Empire in 1235 CE, and quickly developed into a thriving center for trade/cultural exchange between the Eastern and Western worlds.

The city attracted merchants of many different nationalities and faiths, and Medieval sources note that the city displayed an unusual degree of diversity and religious tolerance. It contained 12 different temples devoted to pagan and/or shamanistic traditions, two mosques, one church, and at least one Buddhist temple.

As this article explains:

The city might have been compact, but it was cosmopolitan, with residents including Mongols, Steppe tribes, Han Chinese, Persians, Armenians, and captives from Europe who included a master goldsmith from Paris named William Buchier, a woman from Metz, one Paquette, and an Englishman known only as Basil. There were, too, scribes and translators from diverse Asian nations to work in the bureaucracy, and official representatives from various foreign courts such as the Sultanates of Rum and India.

This diversity was reflected in the various religions practised there and, in time, the construction of many fine stone buildings by followers of Taoism, Buddhism, Islam, and Christianity.

The prosperous days of Karakorum were very short-lived, however. The Mongol capital was moved to Xanadu in 1263, and then to Khanbaliq (modern-day Beijing) in 1267, under the leadership of Kublai Khan; Karakorum lost most of its power, authority, and leadership in the process. Without the resources and support that it had previously received from the leaders of the Mongol Empire, the city was left in a very vulnerable position. The residents of Karakorum began leaving the site in large numbers, until the city had eventually become almost entirely abandoned.

There were a few scattered attempts to revive the city in the years that followed, but any hope of restoring Karakorum to its former glory was then finally shattered in 1380, when the entire city was razed to the ground by Ming Dynasty troops.

The Erdene Zuu Monastery was later built near the site where Karakorum once stood, and pieces of the ruins were taken to be used as building materials during the construction of the monastery. The Erdene Zuu Monastery is also believed to be the oldest surviving Buddhist monastery in Mongolia.

There is very little left of the ruined city today, and this statue is one of the few remaining features that can still be seen at the site. It originally formed the base of an inscribed stele, but the pillar section was somehow lost/destroyed, leaving nothing but the base (which may be a depiction of the mythological dragon-turtle, Bixi, from Chinese mythology).

This statue and the site in general always kinda remind me of the Ozymandias poem (the version by Horace Smith, not the one by Percy Bysshe Shelley):

In Egypt's sandy silence, all alone,

stands a gigantic leg

which far off throws the only shadow

that the desert knows.

"I am great OZYMANDIAS," saith the stone,

"the King of Kings; this mighty city shows

the wonders of my hand."

The city's gone —

naught but the leg remaining

to disclose the site

of this forgotten Babylon.

We wonder —

and some Hunter may express wonder like ours,

when thro' the wilderness where London stood,

holding the wolf in chace,

he meets some fragment huge

and stops to guess

what powerful but unrecorded race

once dwelt in that annihilated place

Sources & More Info:

University of Washington: Karakorum, Capital of the Mongol Empire

Encyclopedia Britannica: Entry for Karakorum

World History: Karakorum

#archaeology#history#anthropology#artifact#ancient history#mongol empire#mongolia#karakorum#middle ages#ancient ruins#art#turtle#bixi#ozymandias#poetry#mythology#genghis khan

152 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Mongol empire in 1276. Pink is sparsely populated

136 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy women's day!

And today mongolian princess Khutulun congratulates you. She was Haidu's daughter, who was a grand grandson of Genghis Khan. Khutulun struggled like a man and ruled armies. She and her father took part in the Civil war in Mongolian Empire.

#khutulun#mongol history#mongol empire#mongolia#woman#women's day#mongolian woman#nomad#female warrior

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

i feel like i would excell as a medieval messenger boy.

open the gates i have a message from the khan.

my lord my duty is to only deliver the message, i do not have a say on the contents of it.

i would advise against that, sire, as a single casualty amongst his diplomats will bring forth the wrath of the great khan upon thy lands.

dream job

#then i would get stabbed by a random prince at age 22 bcuz he didn't like the news i brought#and my homeland would see this as a declaration of war and freaking destroy those who killed me#good stuff#memes#explore#explorepage#funny#fypツ#fyp#hilarious#writers on tumblr#artists on tumblr#female artists#history#history memes#mongolia#mongol empire#medieval history#medieval memes#medieval europe

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

Various sketches and tomfoolery🪤

#the thief and the cobbler#zigzag the grand vizier#thethiefandthecobbler#thief and the cobbler#mongol empire#earth wind and fire#ewf#fanart#the great mouse detective#ratigan#oc#puss in boots#the last wish#sketches

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

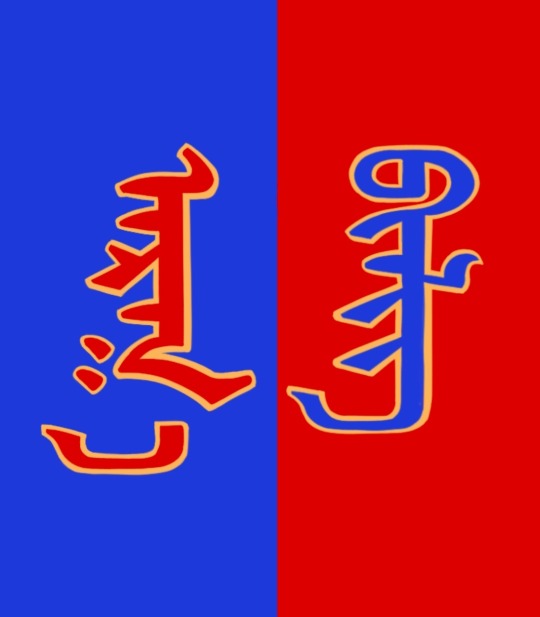

Married Mongolian Women’s Hairstyle in the Yuan Dynasty

Mongolians have a long history of shaving and cutting their hair in specific styles to signal socioeconomic, marital, and ethnic status that spans thousands of years. The cutting and shaving of the hair was also regarded as an important symbol of change and transition. No Mongolian tradition exemplifies this better than the first haircut a child receives called Daah Urgeeh, khüükhdiin üs avakh (cutting the child’s hair), or örövlög ürgeekh (clipping the child’s crest) (Mongulai, 2018)

The custom is practiced for boys when they are at age 3 or 5, and for girls at age 2 or 4. This is due to the Mongols’ traditional belief in odd numbers as arga (method) [also known as action, ᠮᠣᠩᠭᠤᠯ, арга] and even numbers as bilig (wisdom) [ᠪᠢᠴᠢᠭ, билиг].

Mongulai, 2018.

The Mongolian concept of arga bilig (see above) represents the belief that opposite forces, in this case action [external] and wisdom [internal], need to co-exist in stability to achieve harmony. Although one may be tempted to call it the Mongolian version of Yin-Yang, arga bilig is a separate concept altogether with roots found not in Chinese philosophy nor Daoism, but Eurasian shamanism.

However, Mongolian men were not the only ones who shaved their hair. Mongolian women did as well.

Flemish Franciscan missionary and explorer, William of Rubruck [Willem van Ruysbroeck] (1220-1293) was among the earliest Westerners to make detailed records about the Mongol Empire, its court, and people. In one of his accounts he states the following:

But on the day following her marriage, (a woman) shaves the front half of her head, and puts on a tunic as wide as a nun's gown, but everyway larger and longer, open before, and tied on the right side. […] Furthermore, they have a head-dress which they call bocca [boqtaq/gugu hat] made of bark, or such other light material as they can find, and it is big and as much as two hands can span around, and is a cubit and more high, and square like the capital of a column. This bocca they cover with costly silk stuff, and it is hollow inside, and on top of the capital, or the square on it, they put a tuft of quills or light canes also a cubit or more in length. And this tuft they ornament at the top with peacock feathers, and round the edge (of the top) with feathers from the mallard's tail, and also with precious stones. The wealthy ladies wear such an ornament on their heads, and fasten it down tightly with an amess [J: a fur hood], for which there is an opening in the top for that purpose, and inside they stuff their hair, gathering it together on the back of the tops of their heads in a kind of knot, and putting it in the bocca, which they afterwards tie down tightly under the chin.

Ruysbroeck, 1900

TLDR: Mongolian women shaved the front half of their head and covered it with a boqta, the tall Mongolian headdress worn by noblewomen throughout the Mongol empire. Rubruck observed this hairstyle in noblewomen (boqta was reserved only for noblewomen). It’s not clear whether all women, regardless of status, shaved the front of their heads after marriage and whether it was limited to certain ethnic groups.

When I learned about that piece of information, I was simply going to leave it at that but, what actually motivated me to write this post is to show what I believe to be evidence of what Rubruck described. By sheer coincidence, I came across these Yuan Dynasty empress paintings:

Portrait of Empress Dowager Taji Khatun [ᠲᠠᠵᠢ ᠬᠠᠲᠤᠨ, Тажи xатан], also known as Empress Zhaoxian Yuansheng [昭獻元聖皇后] (1262 - 1322) from album of Portraits of Empresses. Artist Unknown. Ink and color on silk, Yuan Dynasty (1260-1368). National Palace Museum in Taipei, Taiwan [image source].

Portrait of Unnamed Imperial Consort from album Portraits of Empresses. Artist Unknown. Ink and color on silk. Yuan Dynasty (1260-1368). National Palace Mueum in Taiper, Taiwan [image source].

Portrait of unnamed wife of Gegeen Khan [ᠭᠡᠭᠡᠨ ᠬᠠᠭᠠᠨ, Гэгээн хаан], also known as Shidibala [ᠰᠢᠳᠡᠪᠠᠯᠠ, 碩德八剌] and Emperor Yingzong of Yuan [英宗皇帝] (1302-1323) from album Portraits of Empresses. Artist Unknown. Ink and color on silk. Yuan Dynasty (1260-1368), early 14th century. National Palace Museum in Taipei, Taiwan [image source].

To me, it’s evident that the hair of those women is shaved at the front. The transparent gauze strip allows us to clearly see their hairstyle. The other Yuan empress portraits have the front part of the head covered, making it impossible to discern which hairstyle they had. I wonder if the transparent gauze was a personal style choice or if it was part of the tradition such that, after shaving the hair, the women had to show that they were now married by showcasing the shaved part.

As shaving or cutting the hair was a practice linked by nomads with transitioning or changing from one state to another (going from being single to married, for example), it would not be a surprise if the women regrew it.

References:

Mongulai. (2018, April 19). Tradition of cutting the hair of the child for the first time.

Ruysbroeck, W. V. & Giovanni, D. P. D. C., Rockhill, W. W., ed. (1900) The journey of William of Rubruck to the eastern parts of the world, 1253-55, as narrated by himself, with two accounts of the earlier journey of John of Pian de Carpine. Hakluyt Society London. Retrieved from the University of Washington’s Silk Road texts.

#mongolia#mongolian#yuan dynasty#mongolian history#chinese history#china#boqta#mongolian traditions#history#gegeen khan#empress dowager taji#mongol empire#William of Rubruck#historical fashion#arga bilig#central asia#central asian culture#mongolian culture#asia

273 notes

·

View notes

Text

During his travels one woman seems to have impressed Marco Polo above all others. Her name was Khutulun, a fierce Mongol warrior princess famed for her fighting prowess.

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

Horse archery and heavy cavalry

While many tend to associate heavily armoured cavalry with tactics similar to Europe in that they are solely lancers, meant to charge into enemy formations and break them, in most of the world heavy cavalry didn't tend to serve solely this role. In essentially all of Asia heavy cavalry tended to be equipped with bows and served the same role as more lightly armoured horse archers while also being able to double as shock cavalry when the situation called for it due to their heavier equipment. These tactics were also adopted in North Africa, due to direct influence from the Turkic slave soldiers in use by the Islamic caliphates.

Of course many people do tend to associate horse archery with lighter cavalry and this is understandable as most horse archers did tend to be more lightly equipped in the steppe armies. But this isn't because they're horse archers, but rather the opposite. Because it was the default for cavalry to be archers, and when one is lightly armoured the best role to serve would be that of a horse archer. However by no means does horse archery require lightly armoured troops.

One specific way of utilizing heavy cavalry, popular all across central and west Asia though by no means limited to it, would be to equip heavy cavalry with lances in addition to their bows. The most famous users of this tactic would probably be the Mongols which made very liberal and effective use of their heavy cavalry in this manner. The cavalry would serve the regular horse archer role at first - harrassing the enemy at range - but when the situation called for it they'd swap to their lances and charge into the weary enemy ranks. If the enemy didn't break immediately (which they often did) they'd pull back, regroup and charge again.

This might then raise the question in some of you which is - how does one carry both a bow and a lance at the same time? Luckily for us, we have got sources for this. Below is a depiction from an early 14th century Ilkhanate manuscript, depicting the lance tied around the foot and arm to leave the hands free for bow- or indeed in this case sword - usage.

Another source for how to hold a lance while using a bow on horseback can be found in the Silahşorname by the late 15th century Ottoman author, Firdevsî-i Rûmî. The translation below was done by a friend of mine:

"The second way is that if you wish to shoot arrows while on top of a running horse, whether it be in battle against an enemy or other places or in hunting, then it’s necessary to secure the lance between the strap of the right stirrup and the horse’s chest while making the horse run. That is to say, put the lance between the strap of the right stirrup and the horse’s chest and tuck its blade high up. As in tuck the lance into your right elbow and have the blade of the lance behind you so that it stays secure. And after that, your horse can run and you can make your shot. Shooting arrows in this way is the legacy of Behram-i Gur, who was the sultan of Persia, he was a hunter and an archer."

The attribution of this technique to the 5th century Behram-i Gur is definitely a fabrication by the author of the book, no doubt to mythicise the usage of the weaponry in this manner. regardless, the technique mentioned is pretty interesting.

While there's scores more to say about this topic I think leaving it here for this time is good enough. I will however leave you with a video series below which is an extremely well researched overview on heavy cavalry in the Mongol armies, and definitely a must watch if you have any interest in this topic.

youtube

73 notes

·

View notes

Note

How many boards would the Mongols hoard, if the Mongol hordes got bored?

I was sad that Calvin came up with that poem then the comic shows him throwing it out because it was the moment I realized I could write my own silly statements, and thus in some ways the dawn of my career as a writer.

Fun trivia, Calvin's full name in Calvin and Hobbes is canonically Calvin L. Biró, he was named after László Bíró, inventor of the ballpoint pen who had died shortly before the comic strip was first published.

79 notes

·

View notes