#or maybe those farmers are taking shots with creed

Text

My reaction to the chain scene:

Me the moment after that scene I realized I had to fight those farmers without nothing but my bare fists and 1 percent health: Don’t this to me! I can’t believe Capcom sold this to the public! 😭

#i swear#it’s me#or maybe those farmers are taking shots with creed#Bcz Leon is hitting them with enough force to kick their heads off#and they’re still GETTING UP#i am afraid#in this game always#leon kennedy imagine#leon kennedy#resident evil 4 leon#leon s kennedy#leon kennedy x reader#leon kennedy x you#resident evil 4#resident evil 4 remake

459 notes

·

View notes

Note

*kisses you* /p

As per my headcanon, Jekyll owns a garden. And I like to imagine that he experiments a bit on some of the plants, ranging from "more colors" "Stonger smell" To "This snapdragon could swallow you whole, but would rather eat raspberries out of your hand like some weird horse"

Jekyll should also own a horse, at the very least every stable in London should know him by name since hes probably too busy to actually take care of a horse 😔. I was about to ask what name Jekyll would give a horse but then I realized he would probably name it after some alchemy person

*slams hands on table* ZOMBIE HORSE. Or ohhhh! Skeleton horse >:3. What would a chuch grim horse look like? Like shadowmere from Skyrim? In fact if shadowmere wasn't made from Sithis Juice™ I'd bet he's a church grim. Theres a stong chance she still could be actually. Shadowmere my beloved <3 hey have you ever played Oblivion? The Khajiits look like the cheeto mascot and being a vampire sucks. But its v fun and I love destroying everyone with that one powerful staff

I think Jekyll would like spiders. They're v cute ::::)

Speaking of, moths are grand and I adore them. I think Luna moths and Comet moths should know each other

Do you like mushrooms/fungi? Do you have a favorite, I adore all mushrooms but I think the Barbie Pagoda, the "Toadstool" Mushroom, and whatever the heck the one that zombifies bugs is called, are my favorites

Favorite video game 🔫

Oh wow I'm really going to try to reply to all of this on my phone Huh.

Anyways! I love that HC and I accept it wholeheartedly, I feel like it would make a lot of sense for him to have a lot of plants bc so many of them can be used in alchemy. Plants are so lovely and I'd like to say that I have a lot but the plants my family have are all like 15 years old and also half dead BC all of us forgot to take care of them. I spontaneously bought a Bride orchid a few months back. It's very dead </3 I'd like to imagine that he has a sun/plantroom in his house and that he would have a lot in the society too, if not for the fact that he doesn't really have time to tend to them, but my version of Jekyll definitely has a lot of plants<3

He definitely should own a horse and that horse is a Clydesdale named Mayhem /j but I like the thought of him having horses. Specifically either those really ragged horses that only farmers use BC they have no better BC he thinks they deserve a good life (and very much will be offended if anyone dares to try to suggest he buys a new horse) or he would have those really, really fancy white purebreeds. Either way he would definitely be a horse girl and one of those that would be obsessed with buying accessories for them. All his horses, tended to by stable boys, hired or otherwise, would all be spoiled rotten <3

(new drinking game; take a shot everytime I use a <3)

I remember watching videos about commanding in skeleton and zombie horses into minecraft and i thought it was THE SHIT when I was a kid! Skeleton horses my beloved!! Henry can have a zombie horse, as a treat. You know Henry with Shadowmare would be absolutely terrifying and so cool... Although I will probably spoil your fun by saying that, at least in folklore, a church grim (of any race or species) would probably just be a black-coloured, ragged looking animal with a slightly ghostly... Vibe to it? Nothing completely demonic about them, they just have That Wrong Vibe and look like a stray/neglected most of the time, I think that’s v fun <3

I’m a fake Elder scrolls fan bc I have only played Skyrim, sadly. I have watched some videos about Oblivion but it was mostly “trying to beat Oblivion with only X” videos and stuff, but I HAVE Seen the khajiits from there and just... Im glad that I’m used to how they look in Skyrim XD

Jekyll would be someone to like spiders and his lab would probably be covered in spiderwebs, not bc he doesn’t clean but bc he would feel bad destroying the beautiful webs. Maybe he would try to genetically enhance a spider to be the size of a puppy? I feel like spiders would be much cuter if they were larger, at least the thicc hairy ones. The spinely ones still freaks me out tho XD

Moths are so fucking beautiful but they are dumb as bricks. A few months ago a moth accidentally came into my room, scared the shit out of me, and then got stuck in the blinds and went back and forth with the length of one of the... Blades of the blinds? Strips? Sounding like a fucking jet engine until my sister caught it and put it outside again. The most common moths I have seen are emperor moths and I think blood vein moths? Very cute when they don’t scare the shit out of me <3

I’m not an expert on them but I think they are cool, as long as I don’t have to touch them most of the time-- fungi, at least, actual edible mushrooms are fine tho. I remember when I was in like... First grade, my class went on a field trip with a lady who owned a funky bus that she used to teach kids about nature and shit, and she taught us a lot about mushrooms and the parts of mushrooms, I think she talked about toadstolls a lot and did the classic “don’t eat the red mushrooms, you will die” speech, and she also gave us speeches about how everything in Australia (which is fun, since we are on the other side of the world) is out to kill you. It was fun <3

ANyways I’m a basic bitch, so I’m going to say that chanterelles and champignon are my favourite mushrooms bc those are some of the only ones I know and they taste v good. I think we are entering chanterelle season here so I’m going to try to convince my parents to buy some to make a stew out off <3<3

It will come as no surprise when I say Skyrim, right? Skyrim and Assassin’s creed Origins/Syndicate. I absolutely love Skyrim and I love AC, I forced my sister to buy Origins bc it was the first AC game I got interested in bc I was in the middle of an Ancient Egypt phase and I fell in love with the franchise. I bought Syndicate premium edition (with all DLCs and extras) for 75sek/7$ bc it was on sale bc it’s such an old game and I absolutely love it, I have been so tempted to make a Syndicate / TGS crossover bc it is basically in the same time period and I would very much like Henry to be the frye twins secret poison supplier. My bff bought me Odyssey when it was on sale for my birthday but I haven’t gotten around to play it yet bc I’m still not finished with Syndicate, and my sister bought me Valhalla for my birthday last year but our computer is a potato and can’t run it. I ruined my Skyrim with too many mods and I haven’t had time to play a lot of games lately, sadly </3

#Ah... rambles my beloved.#you always know how to distract the shit out of me and now im going to see if there are any more ac games on sale <3#ask#darling-dolly-darlene#long post

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

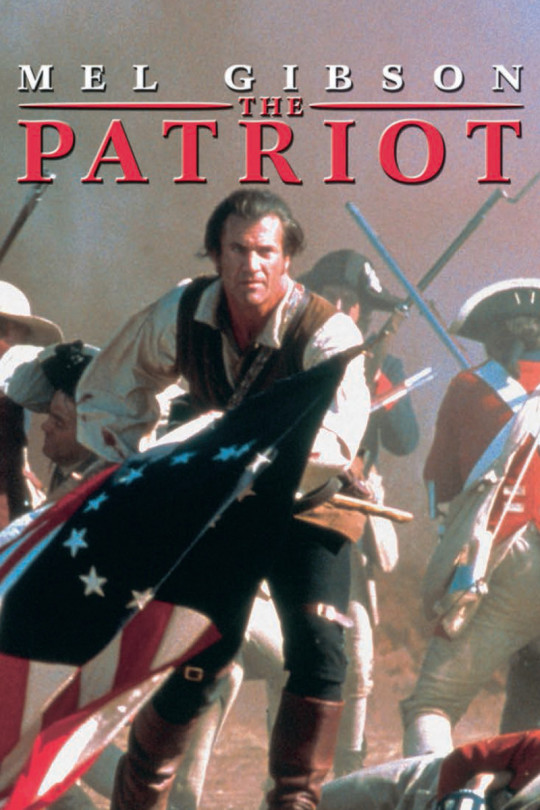

The Patriot is a weird movie that has somehow grown on me? I think it’s a good movie, but I don’t know if it’s a great movie, and it’s about as subtle as a brick to the face. I wouldn’t say it handles the subject matter very well, cutting a few corners to make the story work.

So The Patriot tells the story of Benjamin Martin (Mel Gibson), a South Carolina...farmer? Plantation owner? Whatevs. He’s a widower with several kids and a veteran of the French and Indian War, so despite the beginning of the American Revolution going on, and his oldest son Gabriel (Heath Ledger) joining the Continental Army, he advocates a peaceful solution to the conflict with Britain because he doesn’t want to be drawn into another war. But when a British dragoon leader Colonel Tavington (Jason Isaacs) shows up and shoots his son, Martin joins the war effort, and attacks the British in a brutal guerilla campaign leading a group of local militia.

If you’re from South Carolina, you’ve probably heard about this movie quite a lot, in part because it takes place and was filmed there, but especially because the protagonist is heavily based on American Revolutionary hero and militia leader Francis Marion (and some other South Carolinians from the time but they didn’t have a cool nickname so that’s the one we usually go with). It’s not precisely an accurate depiction of Francis Marion’s life by any means, other than he was a guerilla militia leader in the Revolution that hung out in the swamps. For starters, Benjamin Martin’s anti-slavery, which is not quite the attitude Francis Marion held towards the practice (but fellow SC native and Revolutionary hero John Laurens certainly did!); his plantation is staffed entirely by freedmen--a facet of the character that even Mel Gibson felt was a bit of a cop out, avoiding a chance to do a warts-and-all look at American history. Admittedly, this is a bit much to ask of the movie, I think. And Roland Emmerich, probably.

Still, it’s a bit jarring to have a subplot about one of the militiaman, a black man, finding out that the Continental Army will free any slave that fights for the Revolution for a year when that’s not really a thing that happened at all. And Francis Marion wasn’t nearly as great of a guy as Benjamin Martin; although that may be exactly why there’s a fictional stand-in instead of the actual historical figure in the lead role.

There is often a conversation about the atrocities that the British (mostly Tavington, if we’re being real here) commit during the course of the film. Yes, he’s based off of the real British officer Tarleton, who is infamous in American history for being vicious and giving no quarter. And yes, atrocities happened. And to be clear, in-film, Cornwallis and other Redcoats call out Tavington on his brutality throughout the film, to the point that none of the Brits seem particularly torn up when he dies at the end. But burning a church full of people is a _Nazi war crime._ There’s no record of the British doing anything like that during the Revolution, and so people accuse this movie of demonizing the British. But while the British didn’t do this to American colonists, similar atrocities were committed against the Irish a hundred years before. So no, the British didn’t do this to _US_, but they did do it at some point. That probably doesn’t justify its use here in this movie, but I feel like it’s all important to keep in mind.

This all leads me to the idea of _The Patriot_ not as a history--it’s Hollywood, of course it’s not--but as a sort of mythologized version of the American Revolution. Maybe that’s a weird take, and that might make some people turn off from this movie, but for me it works. I guess that I haven’t been one of those “This movie’s inaccurate, so it SUX!” people for a long time.

The hero of our movie isn’t a man who wants to go to war--he does everything he can to try to avoid going to war, to convince his neighbors that war is not in their best interests, even though he believes in independence for the American colonies. It’s not until the war refuses to leave him alone, and begins to harm his family, that he fully commits to fighting the injustices he sees being perpetrated. Yeah, it’s kind of American _Braveheart_ but is that really a bad thing? As long as we know that’s what it is, I don’t think it is. If there were people out there who took this movie seriously, I don’t know that I’d be as lenient, but I have yet to meet someone whose opinion of history was seriously influenced by this film. Which is probably for the best.

I do understand though that the Plot kind of feels like it’s making the main character way too important to the war effort. It makes it seem as if Benjamin Martin is the only officer in the Continental Army who actually knows what he’s doing against the British. And while I like the character and his arc, I do think it’s a bit silly the way it frames the story in a way that would lead one to think that he’s fighting this war by himself. It’s not fantastic when a story dumbs down the rest of the Good Guys in order to make the Hero stand out--there are ways of accomplishing that without making everyone else incompetent.

And I’ll admit that the story’s structure is a bit… weird, I think. Sometimes Tavington just does terrible things, and I don’t know what this contributes other than adding angst. Towards the end of the movie, he gets information from some colonials before locking them in a church and burning it, but it’s not as if we see him do much with that information. It’s not really Plot Relevant. It just provides motivation for Gabriel to go after Tavington and shoot him with what should have been a fatal shot, and get killed, and give Ben MOAR ANGST. Of course it’s better to show the war as something that has casualties and consequences, but I felt that there were better ways to do it than this.

But this movie is telling an almost mythical epic story set in the American Revolution. Benjamin Martin isn’t a real person; he’s a legendary hero vaguely based off of a real hero. And in epics, seemingly pointless terrible things happen to the hero all the time to make his life suck. And like I said, this is a war movie (albeit, in an 18th century war), made before a lot of the discourse about Fridging came into public forums. Yeah, bad stuff happens, and it doesn’t always seem to make sense--that’s war. And the audience getting invested in the story, and being bothered by character deaths; well that’s kind of the point of character deaths in the first place, isn’t it?

Also it’s kind of an awesome historical action movie--I really like this period in history, because it’s a point where firearms have become commonplace, but haven’t yet become practical enough to completely replace melee weapons in battle. So we’ve got Benjamin Martin taking out Lobsterbacks with muskets, knives, and a tomahawk. It’s great, I love it. This is a huge part of why I love Assassin’s Creed III so much.

Maybe this movie isn’t that great, and I’m just projecting on it because of the lack of good American Revolution movies in the last twenty years…

I dunno. Decide for yourself. It’s a worthwhile watch. It’s got problems for sure, but I think it’s probably one of Roland Emmerich’s greatest films (maybe not a high bar), and a great film on its own merits.

[Also you know Logan Lerman is in this movie? Yeah, Percy Jackson. He’s the youngest son in the family. And Adam Baldwin is a loyalist officer, which is so off from how he’s usually portrayed it’s weird.]

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

By Ingo Schmidt / Socialist Project.

Conservatives: Overestimating their Popularity

“For a Germany in which we live well and happily.” Maybe it was just this less than catchy campaign slogan that cost Angela Merkel’s conservative CDU so dearly at the polls; leaving the party at a record low of 26.8 per cent of the total vote. What is more likely, though, is that the slogan was better at revealing chancellor Merkel’s state of mind – something like: A Germany that should be happy that I govern it so well – than capturing the mood of many of her erstwhile supporters. The conservatives had little sense that terrorism and refugee hysteria were much more than media spectacles. The hysteria indicates how much the so-glad-it’s-not-as-bad-as-elsewhere mood that helped to elect Merkel in the aftermath of the Great Recession and after the Euro-crisis had given way to a much more pessimistic zeitgeist. Locked into the corridors of power, Merkel and her party underestimated the shift from positive to negative outlooks amongst significant parts of the electorate.

Social Democrats:

Stumbling over the equity-employment trade off

The Social Democratic Party (SPD) failed doing the splits. One foot, notably at the beginning of Martin Schulze’s campaign, moved toward genuine social democratic policies. The reward: A massive surge in the polls and party membership. Yet, while the campaign went on, the other foot moved toward the embrace of the social counter-reforms that, in the early 2000s, former chancellor Gerhard Schröder forced through party and parliament at the cost of losing the left wing of the SPD, which merged with the then existing Party of Democratic Socialism into Die Linke. For years, corporate media and Merkel praised the Schröder-cuts as trigger of an employment boom. In fact, Merkel won the last two elections resolutely by propagating the view that Germany had found the magic formula to prosperity while the rest of the world went bust. Crediting Schröder rather than herself as originator of this formula gave her an aura of modesty in a political world mostly inhabited by bullies and big mouths. And, of course, it was a constant reminder to social democratic supporters, who are usually more concerned with social justice than conservatives, that it was ‘their’ chancellor who cut the German welfare state to size.

Vote share in % Change in %

from 2013 election CDU 26.8 -7.4 CSU 6.2 -1,2 SPD 20.5 -5.2 Die Linke 9.2 0.6 Greens 8.9 0.5 FDP 10.7 6.0 AfD 12.6 7.9 The Bavarian CSU (Christian Social Union) and the CDU (Christian Democratic Union) in the rest of the country form a joint conservative caucus in the federal parliament.

SPD – Social Democratic Party of Germany,

FDP – Free Democratic Party (liberal),

AfD – Alternative for Germany (far right). [German federal election, 2017]

The SPD tried twice to cash in on their alleged role in boosting employment. They failed twice and decided to have it both ways this time: Advocating social justice and taking credit for advancing employment at the price of escalating inequality. Voters, proving that they are much smarter than politicians usually think they are, figured that this was a contradicto in adjecto. Some among them may also have had doubts whether a trade off between equality and employment exists in the first place. Whatever issues voters had with the SPD, their electoral results went from bad to worse, reaching, like the CDU, an all-time low of 20.5 per cent.

Die Linke:

Unable to capitalize on widespread tastes for welfare state policies

Die Linke is puzzling. Founded as a merger of left-wing social democrats who defected from Schröder’s Third Way SPD and the PDS, which came out of East Germany’s former ruling Socialist Unity Party, Die Linke had social justice written on its birth certificate. It furthers constant debate around the question how social justice could be realized in a world of class struggle from above and economic stagnation. These debates deliver a plethora of facts and arguments to hammer out election campaigns. One of its frontrunners, Sarah Wagenknecht, routinely deconstructed neoliberal mythologies about the welfare state and union triggered crises and developed alternative policies out of the rubble of these mythologies. This ability made her something like a media darling. But neither Wagenknecht’s media presence nor the endless hours party activists spent on the campaign trail helped to translate the widespread taste for social justice, time and again revealed in opinion polls, into rising support for Die Linke.

When the SPD candidate Schulz hinted at a social democratic turn early in his campaign, SPD ratings shot up. When these hints turned out as fake news, SPD ratings collapsed but it still wasn’t Die Linke that benefited from the widespread taste for social democratic policies that the SPD couldn’t satisfy. Compared to the last elections, Die Linke’s share of the total vote improved by a meagre 0.9% to 9.2 per cent.

The Greens:

From greening the old left to elitist lifestyle policies

The Greens share Die Linke’s inability to capitalize on widespread discontent. However, the difference between the two is that Die Linke aims at turning discontent with economic and social conditions into a social force that could change these conditions. The Greens, once a vanguard of greening old left agendas, would be content to attract voters from governing parties to increase their electoral market share within largely unchanged conditions. As a social force, they mostly represent a saturated middle class engaging in greened conspicuous consumption to distinguish itself from the cheap-deal chasing classes. Locked into self-chosen exclusivity, they have a hard time gaining shares in mass democratic voter markets. But this doesn’t mean that they are locked out from the corridors of power. At the time of writing, it seems that 8.9% of the total vote suffice as entry ticket to a coalition government with the conservatives and the liberal FDP.

The Greens emerged at the tail end of the rebellious 1970s as an attempt to transform the still existing zeal of the new social movements into an institutional presence against the rising tide of neoliberalism. The new social movements, to be sure, were triggered by insufficiencies of the old left. Tragically, efforts to green the old red agenda failed inside the movements and the Green party also. This opened the door for their transformation into a rather elitist middle-class party. A position it shares with the liberal FDP.

Liberals:

Organize opportunism embraces economic nationalism

After WWII, this party of organized opportunism gave democratic cover to some old Nazis, though most of them joined the conservatives, and free traders. This strange mix was only possible under Cold War conditions. When policies of détente softened these conditions and the 68 rebellion signalled the coming of a new world, the FDP shed its Nazis and reinvented itself as a party of social liberalism and became a coalition partner of the SPD in the late 1960s. In the 1950s and into the early 1960s, the still Nazi-enriched liberals had been loyal to the equally Nazi-staffed conservatives. The late 1960s social liberal incarnation of the FDP didn’t last long; it had barely begun when a combination of economic crises and various social movements represented a double threat to profit rates. Under those conditions, the social democratic left failed to forge a bloc with unions and other social movements that would have pushed the entire party from the post-WWII class compromise to a socialist reformism consciously deepening the crisis of profitability to further socialist transformation. Yet, efforts to do so were enough for the liberals to renew their alliance with the conservatives. Being a catchall party with support from farmers, the petty bourgeoisie and even layers of the working class, the conservatives were slow and hesitant to embrace the neoliberal creed capitalists adopted in response to the crisis of profitability.

The liberals with a smaller support base less reliant on the social layers supporting the conservatives became the vanguard of neoliberalism in Germany. They were so true to their principles that eventually many of its long-time supporters realized that they had long denied stakes in the welfare state and that future doses of neoliberal policies might kill these stakes. As a result, the FDP failed to pass the 5% mark necessary to gain seats in parliament in the 2013 elections but, scoring 10.7% of the vote, had quite a comeback this time around. The liberals had refined their neoliberal commitments, inextricably linked to free trade in the past, by calling upon the state to secure the gains from international economic activity for German citizens. In a time of economic instability and stagnation where even many middle-class people fear they might fall behind, this economic nationalism has more voter appeal than the unrepentant free trade commitments of the pre-Great Recession and pre-Euro-crisis years.

Far right AfD:

Neoliberalism wrapped in Deutschland über alles

Even more successful than liberals at rebranding as economic nationalists was the far right AfD by wrapping its programmatic commitment to neoliberal counter-reforms into thick layers of racism, Islamophobia and, more recently, anti-Semitism supplemented with praise for Germany’s Nazi-past. This brew allowed the AfD to increase its vote share by 7.9%, a little more than the losses suffered by the conservatives, to 12.6 per cent. All other parties campaigned in an ideological field demarcated by neoliberal economics, by conjuring up its past glory, like the conservatives, amending it with touches of social justice, green or assertive foreign policies, like the social democrats, Greens and liberals respectively, or by advocating for the transformation of the neoliberal order into a new kind of welfare state or even a socialist order, like Die Linke. The AfD abandoned the economic field entirely and moved on to politically greener, or maybe browner, fields of race and nation. In a softer version these are presented as culturally inherited identities, in a hard-core version they are biologically determined. Deutschland über alles is the key message in both versions.

Fear Takes Centre Stage

All other parties consider the AfD as a threat to democracy and social cohesion in Germany. To be sure, most parts of the Bavarian CSU and parts of the CDU understand this threat as some other party, the AfD, occupying an ideological field they had reserved for themselves in the past even though they made less noise about it than the AfD. Apart from this qualification, the shock about the AfD’s rise is genuine but pretty helpless, too. Expressions of this shock adopt the far right agenda so that the AfD’s preferred scapegoats – refugees – have taken centre stage in political discourse while they are marginalized economically and socially. Other parties don’t share the AfD’s message, at least not as blatantly as the AfD puts it forward. They may even oppose it. But by focusing so much on refugees they contribute to the shift in discourse from economics to race and nation. Sure enough, many people who feel the pinch of economic insecurity see refugees as unwanted competitors for jobs or welfare provisions. This economic rationale would actually be open to debates seeking policies to reconcile domestic concerns about job and income security with refugee concerns about – exactly the same issues. This is what Die Linke tried. Occasionally, Wagenknecht added a dose of anti-refugee sentiment to her economic messaging while other parts of the party came to a moral defense of refugees that put the left classic argument that capitalism is based on a scarcity of jobs on hold as far as refugees were concerned. For most parts of the election campaign, though, Die Linke managed to present refugees as a particularly vulnerable part of a working class undergoing massive transformations.

The recomposition of the working class in Germany, as elsewhere, certainly has something to do with the influx of refugees and immigrants. But it also has to do, in quantitative terms probably more so, with outsourcing, privatizations, relocation of operations and automation. Combined with pressures on wages, the lowering of social standards and public service cuts this recomposition leads to massive insecurities. They are particularly hard felt, though to different degree by different layers of the working class, because long established forms of representation, through unions, parties, civil society organization and the media were thrown into crises by waves of economic restructuring. A decline of membership in unions and civil society organizations, increasing volatility in the electoral system, most recently illustrated by the fall and rebound of the FDP and the rise of the AfD, and the social media spectacle testify to this crisis of representation. This crisis renders frames through which workers and layers of the middle class could make sense of their respective economic and social conditions obsolete. As a result, objectively existing and increasing insecurities are perceived as unintelligible threats. Fear reigns supreme and eclipses reason. The new German angst is projected onto refugees and immigrants. Arriving at a time of present-day insecurities and dismal outlooks onto the future, foreigners who run for their lives or look for a brighter future unleash the ghosts of history amongst wide swaths of the German population. The conservatives were still living in the recent past when Germany looked like an island of stability in a sea of economic turmoil. Pointing at high levels of employment and balanced budgets, they were quiet about increasing inequalities and insecurities. Yet, these are important concerns for growing numbers of people.

Tragically, thinking about economic and social issues is still dominated by the neoliberal imperatives of competitiveness, deregulation and balanced budgets. Alternative ways of economic thinking that can explain growing inequality and insecurity as outcomes of neoliberal policies, thereby articulate growing discontents and rally for policy alternatives, remain in the shadow of the neoliberal populism that dominates public debates for decades. Die Linke tried hard to strike a different economic chord but it either wasn’t heard or didn’t resonate. Economic reasoning and neoliberalism, even if, or maybe because, it is more of a religion than reasoning, are widely seen as one and the same. This is not only true for 99% of economic professors, 90% of politicians but also the vast majority of the population. Consequently, people finding themselves at the losing end of neoliberalism often express their discontent in non-economic terms. That’s why the AfD’s wrapping their own brand of neoliberalism in a diversity of chauvinistic identity covers was so successful. Finding a different economic language that the discontented can understand and clearly distinguish from the neoliberal creed is possibly the key challenge for Die Linke and the left outside the party to counter the pull to the right that currently dominates politics in Germany. •

Ingo Schmidt teaches Labour Studies at Athabasca University and is one of the organizers of the annual World Peace Forum teach-ins in Vancouver. His latest books are The Three Worlds of Social Democracy, Reading ‘Capital’ Today (with Carlo Fanelli) and Capital@150, Russian Revolution@100 (in German).

from Home http://ift.tt/2wz0wdr

0 notes