#people have always been people

Text

Love that Ötzi is on Wikipedia's list of unsolved murders. Don't you worry, buddy, you may have died on a mountain 5500 years ago but we still remember and we are still investigating.

1K notes

·

View notes

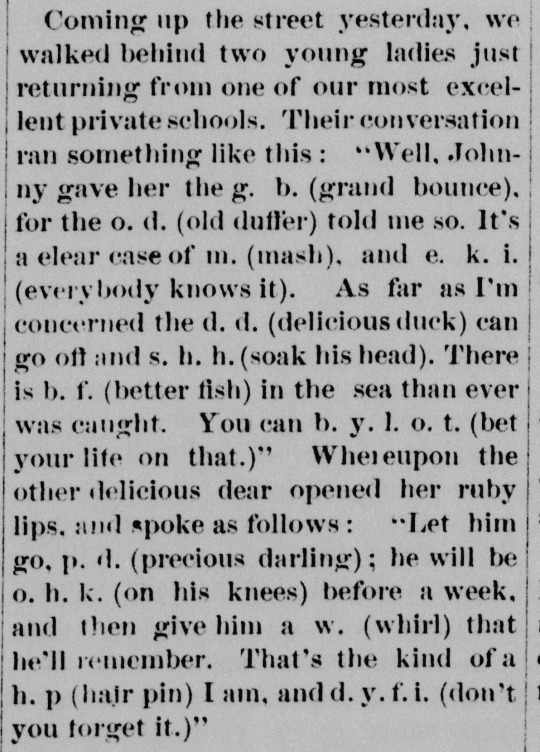

Photo

(source: The Atchison Globe, April 25, 1878.)

#l. o. l. (laughing out loud)#1870s#victorian#history#slang#language#english language#teenagers#kids these days#people have always been people

616 notes

·

View notes

Text

just. the way that ghosts so thoroughly shows that people have always been people. they've always been a little bit messy and a little bit silly and they get mad and they laugh and they learn and they grow and they have forever and will continue to forever. and then when you consider the queer aspect of like. gay people have always been here. robin slept with anyone he wanted to and they raised children as a community. fanny's husband was gay in the 1800s. the captain was gay in 1945. sam and clare had their wedding at button house in the 2020s. people have always been here and sometimes they're gay and sometimes they fight and sometimes they grieve and sometimes they love and sometimes they're mean and sometimes they're kind and they apologize and they play games and they organize clubs and they play pretend and they cry and they live. they're dead but they live. they live.

#do you GET IT!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!#PEOPLE HAVE ALWAYS BEEN PEOPLE#AND IT'S BEAUTIFUL!!!!!!!!!!!!!#WAHHH!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!#bbc ghosts

379 notes

·

View notes

Text

Y'know what's striking about the Demeter section? The first mate.

Specifically, that his first and foremost reaction to the crew's fear is violence. He wants the crew to stop acting afraid, stop bringing up their fears, he assures the captain nothing is wrong and through out it all he threatens the crew with physical assault in effort to basically get them to shut up.

He threatens them with a handpike AFTER a crew member has disappeared, and the captain has shown he is willing to conduct a search for a stowaway.

Idk, it just gets me that we have someone who, when faced with mounting evidence that something is going very, very wrong, to the point of danger to the rest of the crew and himself, threatens disproportionate bodily harm for the mere mention that something is frightening people, and whose ultimate goal is to get everyone to ignore the problem and stop talking about it.

Anyway....bit of plague metaphor this ship...but of course, it's just a metaphor....

470 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Medieval people did this," "medieval people were like that" my dude there are people twenty miles away from me right now who would fight a man over regional differences in what we call water fountains, and we have the internet. You think a bunch of humans whose only contact with their neighbors three hundred miles up the road was some guy who took four weeks to get there on horseback plus also The Church (noted expert in all things that people do and like in every era, never argues with itself), all agree on how to take a bath or cook a turkey just because they happened to live in the same century? If my grandmother knew how some of my friends cook pasta she'd have a stroke. Please.

#this post brought to you by yet another argument over how much “medieval people” bathed#HAVE WE ALL FORGOTTEN THE TWITTER WARS OF 2019 OVER WHO WASHES THEIR LEGS#people have always been people

137 notes

·

View notes

Text

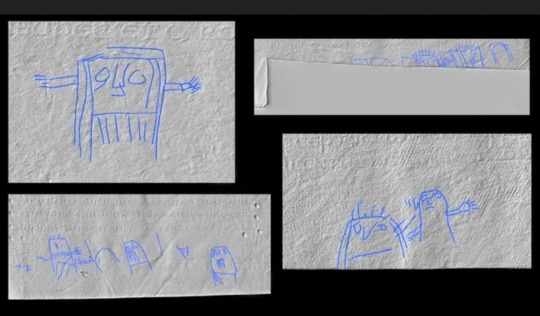

This is a very interesting story in its own right, especially if you're interested in the new techniques being developed to map/study medieval manuscripts, but just look at these utterly charming eighth-century doodles:

(The bottom right need to be made into medieval cartoon characters immediately.)

#history#medieval history#medieval literature#manuscript studies#look at them! i adore these#people have always been people#women in history#(adding since they believe the doodler was a woman)

711 notes

·

View notes

Text

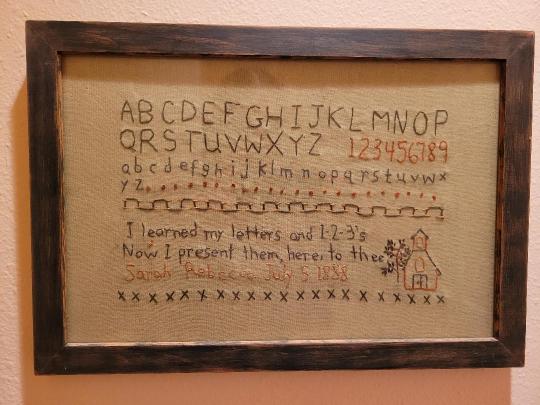

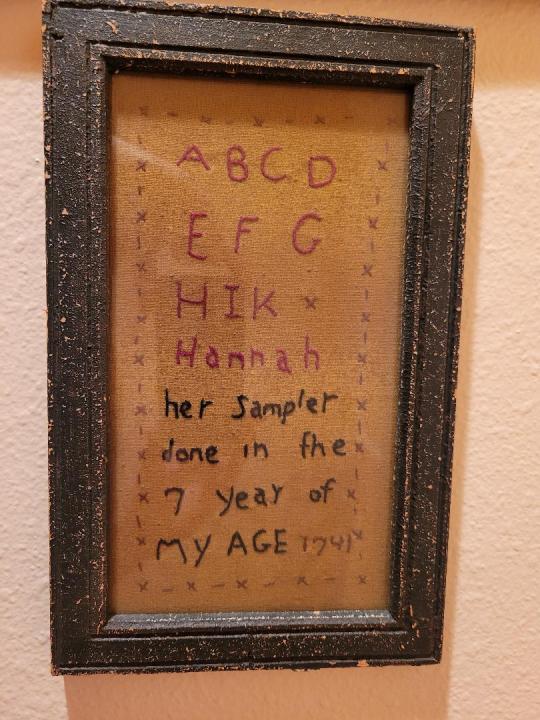

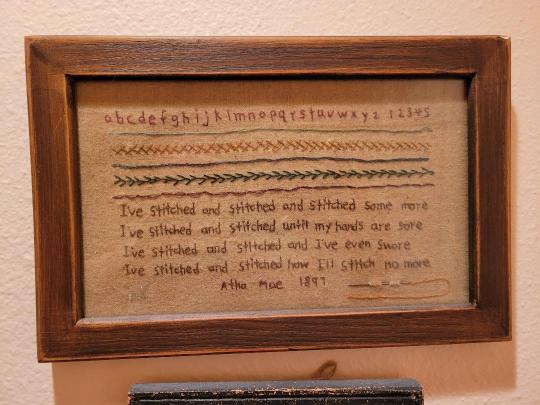

Shoutout to that other post about these

I’m visiting in-laws who own Valuable Art From Previous Centuries, and I did a double-take when I walked past these three.

Needlework samplers from days of yore.

Back in the day, framing these was like putting the big spelling test up on the fridge.

I particularly like that last one, with the needle included because little Atha Mae was done.

#hey that was the same year Dracula came out!#how about that#history#needlework#embroidery#ye olde homework#people have always been people#I wonder how old she was

775 notes

·

View notes

Note

what's your most oddly specific hot take

Hello maggot what a lovely question, here you go:

I believe that OFMD fandom's character Izzy, the subject of much controversy, actually doesn't exist, and so the discourse is unnecessary. He is simply a Freudian projection induced by hallucinogenic rum triggered by childhood boiling of a humanoid potato by Ed.

Shitposters in Ancient Greece and Rome would crush anyone on Tumblr. Has anyone on Tumblr ever run into the prestigious Academy of Plato with a plucked chicken screaming Behold a man? Spat in the face of a rich man in his own home because he told you not to sully the furniture with your spit? Left graffiti on the walls of Pompeii before 70 AD that said, "If you are bored, take a bag of rice, scatter it all over the road. Pick the grains up one by one. Now you have a task."

144 is the sluttiest number ever why does it have to be divisible by so many things? You could tell me 144 is divisible perfectly by 433339 to get a whole number, and I would believe. What a whore, 144.

Not a hot take, but Crowley's hot and I wanna take them on a date.

#good omens mascot#good omens#crowley#weirdly specific but ok#asmi#lgbtqia#maggots#ancient greece#ancient rome#pompeii#ancient history memes#diogenes the cynic#people have always been people#people being people#humans being humans#maths#mathblr#im weird ok#you asked for it#ofmd fandom#ofmd izzy#tumblr#shitposting#izzy hands

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hey so you know how people complain that nowadays the average friendship has been reduced to likes and comments in a post or reactions to instastories? I was just thinking about how before the internet, and a bit before domestic phones, there was the culture of calling cards.

People used to go calling on their social circle, it was a part of the social routine, right. You would go about your acquaintances’ homes paying them a “social visit” — standardly of the brief and socially agreed length of 15 minutes — every so often, as to maintain your acquaintanceship status. But, when you didn’t want to actually go and talk a bunch of nothing or if someone was a bit tiresome or you just didn’t have the time, you could go purposefully at a time you reckoned they weren’t home or available and leave your calling card with the butler and bamf. Your calling card had your name and address and meant “hey, I was here! I thought of you! I’ve made an effort! I’m keeping my side of this relationship up!”

And like… That’s exactly what we do with likes and comments. We’re here just keeping the ties up. And the internet allows us to do it more easily and across any earthly distance. We don’t need to be deeply in contact with all of the people we like. You can still like them a lot and only talk with them briefly between instastory reactions for a while. It doesn’t mean that our relationships are weaker now than they were before! We are actually able to keep up with more of the lives of loved ones from so far away now. Though it might mean that we end up having far too many relationships that we could just let go of, that we don’t really vibe with or care about, and it’s more than okay to drop those!

But in the end, social media, the core of it, before all the troubles of excess and overstimulation, is just what people have done for centuries. Checking in on each other and waving hello… and idk I just think that’s really neat

#people have always been people#we also had letters and daily journals bits transcribed onto letters which is basically twitter#but that’s subject for another post#I love that so much#how much do i need to tag this for a chance of finding it later#history#social media#internet#carrot.braindump#carrot.txt#jane austen#classical literature

557 notes

·

View notes

Text

Love how much of the history of editing is just people going "He would not fucking say that" about like. The characters in their favorite classical epic.

#sorry Aristophanes Zeus is still a dick in the Odyssey#love what an ancient and storied tradition it is for people to look at a text and go#'well OBVIOUSLY the author couldn't have meant THAT#only i understand his True Vision'#love to think about editors in Byzantium getting into fights over their blorbos#people have always been people

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the ruins of Pompeii, there is a room inside a house where two men were painting on the day Mt. Vesuvius erupted in AD 79.

The master painter was at work on the fresco itself, twining vines in green, men and women looking out of the image to one side. His partner, probably an apprentice or lesser, younger painter, was laying down fresh plaster nearby. We know it was fresh because the pumice left significant pockmarks in it as it dried that we can still see today.

There are holes where a shelf stood holding the different colors of paint, in the wall just below the unfinished fresco. We found jars of paint on the floor - red green blue white yellow black. We found his tools, the brushes and the pot of lime that kept the paint wet.

He spilled lime on the painting.

We can tell that, too. It is caked clear as day over the unfinished work.

In a documentary I am watching, an Italian anthropologist discussing the moment of eruption looks to the cameraman and says, with real sincerity, "We found their tools, but we didn't find them. We hope that they ran away, that they survived."

Next door, a baker left his livestock behind when he fled. We found the skeletal remains of the animals who helped to move the millstone, but we did not find the baker.

Not that we are certain of, anyway.

I just wanted to take a moment to think about a modern Italian anthropologist looking at unfinished paintings and bread turned to stone by ash and time, hoping to himself that those people made it out in time.

We are separated by almost two thousand years, but we still have empathy for lives facing terror beyond their understanding. We still hope against hope that two painters ran out of town and made a new life somewhere else, that they escaped before the final pyroclastic flows descended.

We hope the baker moved to another town.

We recognize ourselves in what was left behind, and hope that these people - who could have been us, but for a trick of time and place - had a fighting chance to survive.

I just.

Sometimes, I love people.

I love us.

420 notes

·

View notes

Photo

This is my 12th year posting Dear Santa letters on tumblr.

Over the last decade+ I have read more letters than I could ever count. This year alone I probably spent 50+ hours and read well over a thousand letters just to find the 50 or so I’m posting.

Publishing letters to Santa in the newspaper first became popular in the mid-1890s.

In large cities Dear Santa letters often acted as a method of getting needed clothing and supplies to impoverished children when parents might be ashamed to ask for charity. Subscribers to the newspaper could chose a child’s letter and provide the items they asked for. The most common requests were shoes and coats.

Sometimes newspapers offered prizes for the best letter (which I suspect often acted as another clandestine form of charity as the winners were often letters asking for basic clothing and school supplies.) Though these prizes could range from the ordinary (a sled or a doll) to the extravagant (a $20 gold piece or a live pony.)

Many local stores would enter children in a drawing if they mentioned the store in their letter - which on occasion would result in children hilariously name-dropping every store in town just in case.

Writing Dear Santa letters was commonly an activity done at school, often following some rough form letter. These letters are fairly easy to spot due as they often hype up what a good student the child was and include effusive praise for their teacher (who would likely see the letter before it was sent.)

Through Dear Santa letters you can see how Christmas traditions vary and evolve from place to place. Some places the presents go under the tree, others on it. Some place Santa brings the tree himself and sets it up.

Stockings were hung over the fireplace, or on the doorknob, or at the end of the bed, or by the kitchen stove.

In the Deep South fireworks are were the stocking-stuffer of choice, while fresh fruit, nuts and candy were popular everywhere.

The traditional milk & cookies left for Santa didn’t become popular until the 1930s, though that was hardly the beginning of leaving Santa something to eat. Popular choices prior to the 1930s included cake, donuts, “lunch” (it’s always lunch for some reason, never dinner), and “just help yourself to whatever’s in the kitchen.”

Dear Santa letters offer a rare chance to see history unfold through the eyes of children - often in their own creatively spelled words.

1914′s “Remember the children in Belgium” becomes 1918′s “Please visit my brother in France”.

During the Great Depression the very commonly seen phrase “I know you’re poor this year too Santa” gives a glimpse into parents attempts to explain to their children why they might not be getting as much this year.

1939′s “Be careful flying over Europe” becomes 1945′s “Since the war is over you’re making bb-guns again right?”

Requests for toy flying machines become aeroplanes become fighter jets become space shuttles.

Dolls and wagons become Shirley Temple merchandise and Erector Sets become Barbies and Star Wars action figures.

But despite all these changes one thing remains clear throughout 130+ years of letters to Santa - despite the rapidly changing world around them - children have always been children.

I hope you enjoy these letters as much as I do! (All twelve years of posts are tagged “Dear Santa” if you’d like to see more than just this year’s selection.)

Hapy Holadays and Marry Crimes

#every single note comment and tag I get on these posts makes my xmas brighter so thank you <3#Dear Santa#blogkeeping#people have always been people#history#yes I was going to post before I started posting letters but I did not because I'm me

588 notes

·

View notes

Text

The dust pan was invented in the mid to late 1800's

While it is comforting to know that that one little line that will just not be swept up has annoyed me, my mother, my gran, my great gran, my great-great gran, my great-great-great gran, and possibly even my great-great-great-great gran

It does make me wonder, what did my great-great-great-great-great gran do in 1840? What did she doooo? How did she sweep the hearth!?

#people have always been people#I HAVE QUESTIONS#Semantic cessation#The word has lost all meaning#Thinking thoughts#I should be working

116 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bought a used book today with an inscription written to a grandmother in 1902.

34 notes

·

View notes

Note

Was marriage as bad as it sounds during Jane Austen's time? From what I've heard, a woman with the means to stay single would be stupid to want marriage. They were considered property and lost any semblance of independence. Unless you really trust the guy and loved them, it seems like a horrible gamble.

A show made a joke about her being a lesbian because she never got married, which I didn't know. It just confuses me because she wrote so many romance books. I'm wondering if she wrote that way because marriage was purely a practical decision and she was a lesbian or asexual, or if marriage was just a horrible decision altogether.

That joke really rubs me the wrong way, especially in an era where man where scarce because they were fighting Napoleon! Not that there is anything wrong with being queer, but just because a woman with very little fortune didn't manage to marry doesn't mean she didn't want to.

It seems to be pretty well documented that Jane Austen loved/liked at least two men, Tom LeFroy and an unnamed clergyman, but neither proposed. The only man who did propose, Jane Austen decided against.

As for marriage in general, I am sure most marriages were nothing special but fine. I mean, a lot of people especially in the gentry class are marrying for wealth and rank and hoping they also like the person. Freakenomics talked about an analysis that showed most couples in the aristocracy just stopped having kids after the heir and the spare, except during one period where many members of the nobility married "down". Those couples kept having kids, probably because they actually loved each other. Which says a lot about the average upper class marriage.

People would also think about marriage differently than we would today in Western countries. I don't think anyone goes into marriage like Charlotte Lucas, because we don't have to. Women can get their own jobs and, while stigma has not been erased, staying single is no longer a huge taboo. But Charlotte and probably many other women went in knowing that neither side was in love, they were signing up for a roommate with procreation benefits. So if you husband did stray you might not even mind (as long as he didn't bring home any diseases and was discreet).

Most marriages we see in Jane Austen are fine, but not a huge romance. Take Sir John and Lady Middleton, they get along fine but have nothing in common. Clearly they have sex (4 children), but Sir John is getting companionship from other people, like Mrs. Jennings who he actually gets along with great. So they are both making it work and not expecting that their marriage partner will be everything to them. We also see marriages in Jane Austen where the woman is clearly in control (Fanny Dashwood).

Now the problem with Regency society and societies today that make divorce very difficult is not that suddenly all men are abusive, but that women (and men) have an extremely difficult time getting out of bad marriages. There is still divorce stigma of course, and even within Canada it matters how religious your family is, but the average person would not tell an abused partner to just stay to preserve their family dignity (I hope).

Throughout all of human history, let's say roughly 20% of marriages are great, 60% are fine/mediocre (nothing to write home about but your sex roommate is pretty chill), and 20% were bad. I don't think you can ever change the % that are bad, but what you can change is how easily people can escape from that bad situation. No fault divorce, abuse shelters, understanding family/friends, women being able to work, and birth control all help people to get out of abusive situations.

Also, even though a married woman lost some legal rights, it wasn't like she had a lot to begin with. A woman basically goes from the control of her father to the control of a husband. Married women didn't require chaperones so they probably on average had more freedom of movement than single women. In both Wives & Daughters (Elizabeth Gaskell) and Lady Susan (Jane Austen), married women travel to London solo during the season. An unmarried woman could not do that!

In Austen's novels, it's pretty clear the best possible position for a woman was rich widow. There you have freedom of movement, your own money, and social acceptability. And as for not marrying, even rich women like Caroline Bingley and Mary Crawford are trying to marry, not attempting to stay single. The social cost of spinsterhood was just too high.

Oh, and for a fascinating dive into lower class marriages, check out The Five, either the podcast or the book. Really great read.

#question response#people have always been people#history#marriage#jane austen#wives and daughters#lady susan#elizabeth gaskell#learning about history has made me an absolute fan girl of no fault divorce#but it's not like the past was some horror story#bad marriages still happen today#and getting people out is hard

63 notes

·

View notes

Note

How accurate is the ‘medieval peasants worked less then we do today’ statement? I looked it up because I find it very hard to believe, but had trouble making sense of it since history is not my strong point.

The answer to this is complicated, and represents a lot of (indeed, often erroneous) assumptions about past and present alike. Either the past is presented as a terrible place where everyone was miserable and dirty and assaulted all the time, or as an essentially more idyllic and pastoral place where people didn't have to contend with capitalism, credit scores, minimum wages, underpaid work, and all the other onerous apparatus of the modern economic system. Of course, neither the excessively bad or the excessively good version is true, and usually reveals more about the point that the modern debate wants to make, rather than anything to do with history itself.

First, I would like to note that the whole "all non-king medieval people were peasants" stereotype likewise really grinds my gears, and it is often presented uncritically in claims of this type, clearly intended to draw a parallel between overworked medieval people and overworked modern people. Which is fine, but again, not entirely accurate. As should be obvious to anyone who thinks about it for two seconds, medieval society consisted of all kinds of people and all kinds of occupations, both skilled and unskilled. Like, who do y'all think built the cathedrals? A bunch of random grain harvesters from nearby Podunkville? There were brute laborers who pushed wheelbarrows and hauled stones and etc, but there were also highly educated architects and engineers, who knew how to do things like make sure Durham Cathedral would minutely adjust over hundreds of years to the boggy ground it was built on, and not just fall down. There were master artisans, masons, glassworkers, sculptors, carpenters, etc etc. (See the creator of a recent "medieval" Netflix show claiming that medieval people had no use for art and me wanting to kick him like a football into the stratosphere). In towns, there were merchants, brewers, embroiderers, greengrocers, butchers, bakers, everything else you need to run a basic local economy. There were soldiers and mercenaries and other military occupations, which became increasingly professionalized throughout the medieval era and not just a matter of recruiting the local guys from down the road. There were priests and clerics and an extensive church bureaucracy. There were academics and professors and scholars and writers. Etc etc etc.

Anyway, the point is that when you're talking about medieval peasants, you're probably referring to the people who lived in largely rural or agrarian environments and made their living primarily from subsistence farming and animal husbandry for a landlord. Obviously, they did work hard in physically grueling occupations (though they were generally not malnourished and starving, as I have written about before, except in years of bad famine or crop failure, and then their wealthier employers would suffer too, because they all existed in the same material goods universe, whereas the rich and poor are millions of miles apart today). Their wages were often low, and even in the absolute worst of the Black Death’s first wave in 1349, King Edward III of England issued the Statute of Pleading that attempted to keep wages down and prevent peasants from negotiating for higher rates, even in the middle of a literal fucking apocalyptic plague and crushing labor shortage. (He was ultimately not successful). Widespread discontent with the exploitation of the peasantry, the crushing tax rates to fund pointless foreign wars, and other oh-hey-that-sounds-familiar problems led to the Peasants' Revolt in 1381, and the widespread popularity of the Lollards, a social and religious reform movement who criticised the static hierarchy and endemic inequality of medieval European society. So there were obviously some of the same problems as there are today, especially in regard to economic inequality and systemic oppression, and medieval peasants, far from being stupid sheep who just put their heads down and took it, were just as involved in trying to organise movements and protests to change it.

However, medieval peasants did not exist in global capitalism (obviously) and thus both their work and the reason for it was different. This was before the Protestant Ethic of the late 19th/early 20th century, that explicitly linked religious salvation with hard work in the capitalist system. Martin Luther bitched about indulgences so much because it was an accepted system to just pay the church something and be like "okay I'm good, I can kick back and not worry about it." (The medieval Catholic church had many, MANY problems, but the fact that Luther is so often presented as the "good guy" heroically saving these lazy dissolute people tells you all you need to know about how Protestant triumphalism informs Western historiography). In 1215, at the Fourth Lateran Council, Pope Innocent III had to issue an explicit degree to order people to go to church or take communion more than once a year, which he would not have had to do if they were all mindlessly devoted zealots who spent every waking moment there. Medieval people liked to sleep late and chill out on Sunday, just like modern people do now.

Obviously, religion was a more explicit and structured part of their lives than it generally is now, but sometimes the "medieval people worked less" argument is presented as the all-powerful and Machiavellian church craftily providing the people with a lot of public holidays so they didn't revolt against them. As noted, medieval people complained about and ignored and rebelled against the church anyway, and anyone who ever tells me that they were all uniform and brainwashed and always accepted the Catholic church's view on things needs to read one (1) book on the 13th century. Besides, the church just never had that level of total control over society anyway, and this presumes that everything they did was in deliberate bad faith solely to preserve their secular/social power -- which, while secular/social power was also often at stake, is likewise a wildly simplistic misreading of how things actually worked, and what the church actually wanted to do.

There were indeed a lot of public holidays, both religious (i.e. saints' days) and folk (Lammastide, the harvest, Celtic festivals, etc), where people weren't expected to work, and/or to go to church instead. As noted re: Pope Innocent and his struggles in this department, this was often not necessarily the case. There were also ordinary community holidays like house-raisings, weddings, christenings, Christmas, etc etc., where people could (and did) often have a good time for days. There were fairs, tournaments, carnivals, markets, and other opportunities for leisure or to attend entertainment events. So it certainly wasn't the case that peasants were always slaving away with no respite, and that if they weren't working, they were in church. They also didn't have to work for their entire lives; elderly peasants could retire and be supported on a portion of the overall estate yield, in medieval social security, and if this wasn't given to them, they could and did sue their landlords to get it. So yet again, medieval life was NOT just nothing but filth and misery and being worked until you dropped. People are people. They have lived as people in all ages and eras of the world. They have enjoyed themselves and worked and lived and died. We do need to examine the very real problems of the modern world, but I continue to hope, however vainly, that we don't need to keep relying on excessively distorted versions of the medieval world to do it.

512 notes

·

View notes