#puget sound navy yard

Text

USS FRANKLIN (CV-13) at Puget Sound Navy Yard, Washington after repairs.

Note: "she had been repainted in Ms. 21 camouflage; two lattice radio masts abaft the island had been removed; three quad 40's had been added starboard amidships, just under the island."

Date: January 31, 1945

source

#USS FRANKLIN (CV-13)#USS FRANKLIN#Essex Class#Aircraft Carrier#Carrier#Warship#ship#United States Navy#U.S. Navy#US Navy#USN#Navy#Puget Sound Navy Yard#Puget Sound#Washington#West Coast#World War II#World War 2#WWII#WW2#WWII History#History#Military History#January#1945#my post

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

West Virginia off Puget Sound Navy Yard, 2 July 1944

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

The first three aircraft carriers of the United States Navy at the Puget Sound Navy Yard in 1929. USS Langley (CV-1) is at the bottom of the photo with the Lexington class aircraft carrier USS Saratoga (CV-3) tied up to the same pier. Her sister, USS Lexington (CV-2) is at the top of the photo. Saratoga wore a black recognition stripe on her funnel to differentiate her from Lexington early in their careers.

Langley displaced just under 14,000 tons at full load. In comparison, the Lexington class displaced over 47,000 long tons at full load, over three times that of Langley!

28 notes

·

View notes

Photo

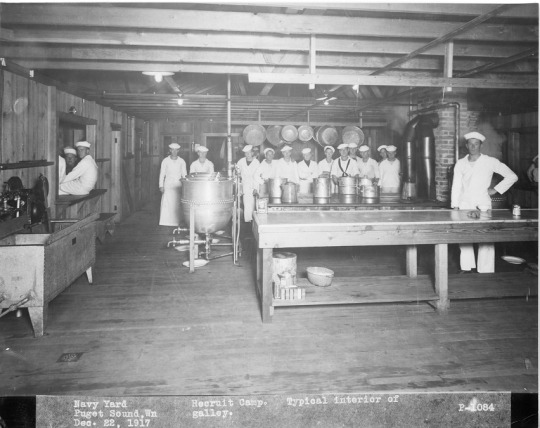

Galley at recruit camp, Navy Yard, Puget Sound, 12/22/1917.

Record Group 71: Records of the Bureau of Yards and Docks

Series: Photographs of Construction Progress and Completion of U.S. Naval Shore Installations and Shipyards

Image description: Sailors standing in a galley (kitchen). Large pots and pans hang from the ceiling and sit on a table-sized stove. The sailors stand behind the stove, wearing white uniforms, long aprons, and “dixie cup” hats cocked at various angles.

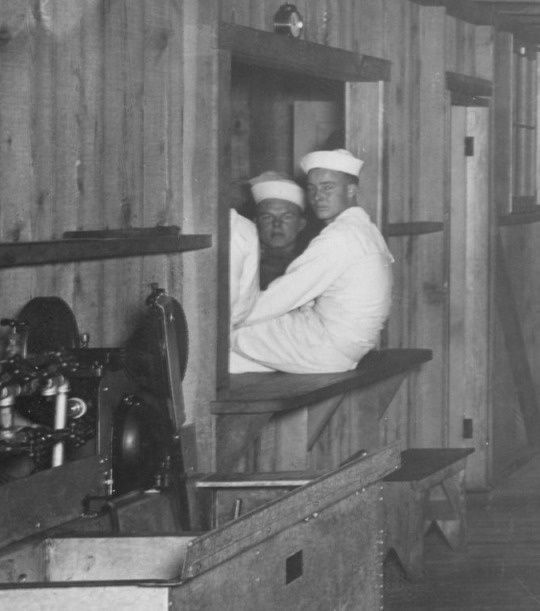

Image description: Zoomed-in portion of image, showing a sailor sitting on the shelf of a pass-through window to another room, looking over his shoulder at the camera.

#archivesgov#December 22#1917#1910s#World War I#WWI#military#U.S. Navy#USN#Puget Sound#galley#kitchen

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

FIRST PICTURE OF LEX AND SARA TOGETHER

"Uncle Sam’s $100,000,000 sisters pose for their first picture together. The giant new airplane carriers Lexington (left), and Saratoga, tide up at the

Puget Sound Navy Yard at Bremerton, Wash., where they are undergoing engine readjustments to bring their speed up to the specified figure. This is the first time since they were launched that the big ships have been close enough to be photographed together."

Evening Star (Washington DC), September 24, 1928

Note that Saratoga doesn't have her distinctive black stripe on the funnel. This was added after their first Fleet Problem participation in Jan 1929.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

This iconic photograph was taken on May 29, 1919.

It features women working as rivet heaters and passers at Bremerton’s Puget Sound Navy Yard just after the end of World War I.

The Shipyard’s workforce increased from 1,500 in early 1916 to more than 6,500 by late 1918. Many new hires were women. They worked in offices as administrative assistants, in the shops operating machinery, and in the docks as rivet heaters and passers. These women foreshadowed the arrival of “Rosie the Riveter” during World War II. Source

0 notes

Link

Check out this listing I just added to my Poshmark closet: Postcard Vintage USS California Puget Sound Navy Yard Battleship 0549.

0 notes

Photo

Women at the Puget Sound Navy Yard. Female Rivet Heaters and Passers, 1919, Puget Sound Navy Yard

0 notes

Text

• Doris Miller

Doris "Dorie" Miller was a United States Navy cook third class. He was the first black American to be awarded the Navy Cross, the second highest decoration for valor in combat after the Medal of Honor.

Miller was born in Waco, Texas, on October 12th, 1919, to Connery and Henrietta Miller. He was named Doris, as the midwife who assisted his mother was convinced before his birth that the baby would be a girl. He was the third of four sons and helped around the house, cooked meals and did laundry, as well as working on the family farm. He was a fullback on the football team at Waco's Alexander James Moore High School. He began attending the eighth grade again on January 25th, 1937, at the age of 17 but was forced to repeat the grade the following year, so he decided to drop out of school. He filled his time squirrel hunting with a .22 rifle and completed a correspondence course in taxidermy. He applied to join the Civilian Conservation Corps, but was not accepted. At that time, he was 6 feet 3 inches (1.91 m) tall and weighed more than 200 pounds (91 kg). Miller worked on his father's farm until shortly before his 20th birthday. Miller's nickname "Dorie" may have originated from a typographical error. He was nominated for recognition for his actions on December 7th, 1941, and the Pittsburgh Courier released a story on March 14th, 1942, which gave his name as "Dorie Miller". Since then, some writers have suggested that it was a "nickname to shipmates and friends."

Miller enlisted in the United States Navy for six years on September 16th, 1939. He did his recruit training at Naval Station Norfolk in Virginia, then was promoted to mess attendant third class, one of the few ratings open at the time to black sailors. After training school, he was assigned to the ammunition ship Pyro (AE-1) and then transferred on January 2nd, 1940, to the Colorado-class battleship West Virginia (BB-48). It was on the West Virginia where he started competition boxing, becoming the ship's heavyweight champion. In July, he was on temporary duty aboard the Nevada (BB-36) at Secondary Battery Gunnery School. He returned to the West Virginia on August 3rd. He was promoted to mess attendant second class on February 16th, 1941.

Miller was a crewman aboard the West Virginia and awoke at 6 a.m. on December 7th, 1941. He served breakfast mess and was collecting laundry at 7:57 a.m. when Lieutenant Commander Shigeharu Murata from the Japanese aircraft carrier Akagi launched the first of seven torpedoes that hit West Virginia. The "Battle Stations" alarm went off; Miller headed for his battle station, an anti-aircraft battery magazine amidships, only to discover that a torpedo had destroyed it. He went then to "Times Square" on deck, a central spot aboard the ship where the fore-to-aft and port-to-starboard passageways crossed, reporting himself available for other duty and was assigned to help carry wounded sailors to places of greater safety. Lieutenant Commander Doir C. Johnson, the ship's communications officer, spotted Miller and saw his physical prowess, so he ordered him to accompany him to the conning tower on the flag bridge to assist in moving the ship's captain, Mervyn Bennion, who had a gaping wound in his abdomen where he had apparently been hit by shrapnel after the first Japanese attack. Miller and another sailor lifted the skipper but were unable to remove him from the bridge, so they carried him on a cot from his exposed position on the damaged bridge to a sheltered spot on the deck behind the conning tower where he remained during the second Japanese attack. Captain Bennion refused to leave his post, questioned his officers and men about the condition of the ship, and gave orders and instructions to crew members to defend the ship and fight. Unable to go to the deck below because of smoke and flames, he was carried up a ladder to the navigation bridge, where he died from the loss of too much blood despite aid. He was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor.

Lieutenant Frederic H. White had ordered Miller to help him and Ensign Victor Delano load the unmanned number 1 and number 2 Browning .50 caliber anti-aircraft machine guns aft of the conning tower. Miller was not familiar with the weapon, but White and Delano instructed him on how to operate it. Delano expected Miller to feed ammunition to one gun, but his attention was diverted and, when he looked again, Miller was firing one of the guns. White then loaded ammunition into both guns and assigned Miller the starboard gun. Miller fired the gun until he ran out of ammunition, when he was ordered by Lieutenant Claude V. Ricketts to help carry the captain up to the navigation bridge out of the thick oily smoke generated by the many fires on and around the ship; Miller who was officially credited with downing at least two enemy planes. "I think I got one of those Jap planes. They were diving pretty close to us," he said later. Japanese aircraft eventually dropped two armor-piercing bombs through the deck of the battleship and launched five 18-inch (460 mm) aircraft torpedoes into her port side. When the attack finally lessened, Miller helped move injured sailors through oil and water to the quarterdeck, thereby "unquestionably saving the lives of a number of people who might otherwise have been lost." The ship was heavily damaged by bombs, torpedoes, and resulting explosions and fires, but the crew prevented her from capsizing by counter-flooding a number of compartments. Instead, West Virginia sank to the harbor bottom in shallow water as her surviving crew abandoned ship, including Miller; the ship was raised and restored for continued service in the war. On the West Virginia, 132 men were killed and 52 were wounded from the Japanese attack. On December 13, Miller reported to the heavy cruiser Indianapolis (CA-35).

On January 1st, 1942, the Navy released a list of commendations for actions on December 7th. Among them was a single commendation for an unnamed black man. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) had asked President Franklin D. Roosevelt to award the Distinguished Service Cross to the unknown black sailor. The Navy Board of Awards received a recommendation that the sailor be considered for recognition. On March 12th, an Associated Press story named Miller as the sailor, citing the African-American newspaper Pittsburgh Courier; additional news reports credited Lawrence D. Reddick with learning the name through correspondence with the Navy Department. In the following days, Senator James M. Mead (D-NY) introduced a Senate bill to award Miller the Medal of Honor, and Representative John D. Dingell, Sr. (D-MI) introduced a matching House bill. Miller was recognized as one of the "first US heroes of World War II". He was commended in a letter signed by Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox on April 1st, and the next day, CBS Radio broadcast an episode of the series They Live Forever, which dramatized Miller's actions. Black organizations began a campaign to honor Miller with additional recognition. On April 4, the Pittsburgh Courier urged readers to write to members of the congressional Naval Affairs Committee in support of awarding the Medal of Honor to Miller. On May 11th, President Roosevelt approved the Navy Cross for Miller. On May 27th, Miller was personally recognized by Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, Commander in Chief, Pacific Fleet, aboard the aircraft carrier Enterprise (CV-6) at anchor in Pearl Harbor. Nimitz said of Miller's commendation, "This marks the first time in this conflict that such high tribute has been made in the Pacific Fleet to a member of his race and I'm sure that the future will see others similarly honored for brave acts."

Miller was advanced in rank to mess attendant first class on June 1st, 1942. On June 27th, the Pittsburgh Courier called for him to be allowed to return home for a war bond tour along with white war heroes. On November 23rd, Miller returned to Pearl Harbor and was ordered on a war bond tour while still attached to Indianapolis. In December, and January 1943, he gave presentations in Oakland, California, in his hometown of Waco, in Dallas, and to the first graduating class of black sailors from Great Lakes Naval Training Station. He was featured on the 1943 Navy recruiting poster "Above and beyond the call of duty", designed by David Stone Martin. He then reported to Puget Sound Navy Yard at Bremerton, Washington on May 15th, 1943 when he was assigned to the newly constructed escort carrier Liscome Bay (CVE-56). He was advanced in rank to cook third class on June 1st. The ship had a crew of 960 men, and its primary functions were to serve as a convoy escort, to provide aircraft for close air support during amphibious landing operations, and to ferry aircraft to naval bases and fleet carriers at sea. After training in Hawaii waters, Liscome Bay left Pearl Harbor on November 10th, 1943 to join the Northern Task Force, Task Group 52. Miller's carrier took part in the Battle of Makin (invasion of Makin by units of the Army's 165th Regimental Combat Team, 27th Infantry Division) which had begun on November 20th. On November 24th, the day after Makin was captured by American soldiers and the eve of Thanksgiving that year (the cooks had broken out the frozen turkeys from Pearl Harbor), the Liscome Bay was cruising near Butaritari (Makin's Atol's main island) when it was struck just before dawn in the stern by a torpedo from the Japanese submarine I-175 (fired four torpedoes at Task Group 5312). The carrier's own torpedoes and aircraft bombs including 2,0000 pounders were detonated a few moments later, causing the ship to sink in 23 minutes. There were 272 survivors from the crew of over 900, but Miller was among the two-thirds of the crew listed as "presumed dead". His parents were informed that he was missing in action on December 7th, 1943. Liscome Bay was the only ship lost in the Gilbert Islands operation.

A memorial service was held for Miller on April 30th, 1944, at the Second Baptist Church in Waco, Texas, sponsored by the Victory Club. On May 28th, a granite marker was dedicated at Moore High School in Waco to honor him. Miller was officially declared dead by the Navy on November 25th, 1944, a year and a day after the loss of Liscome Bay. One of his brothers also had served during World War II. Miller was 24 years old at the time of his death. Miller's legacy continues in many memorials to his service. Doris Miller Memorial, a public art installation honoring Miller on the banks of the Brazos River in Waco, Texas. A bronze commemorative plaque at the Doris Miller Park housing community located near Naval Station Pearl Harbor; organized by the Alpha Kappa Alpha sorority and dedicated on October 12th, 1991, which would have been Miller's 72nd birthday. Even the U.S Navy honored Miller with the USS Miller (FF-1091), a destroyer escort (reclassified as a Knox-class frigate on June 30th, 1975) was commissioned on June 30th, 1973, in honor of Miller. Miller's likeness and story has also been portrayed in films, such as Miller being awarded the Navy Cross was portrayed in the 2019 film Midway. In Michael Bay's 2001 film Pearl Harbor, Miller is portrayed by actor Cuba Gooding Jr. Although he is not identified by name, Miller is portrayed by Elven Havard in the 1970 film Tora! Tora! Tora!

#second world war#world war ii#world war 2#wwii#military history#history#biography#black history month#black history#u.s history#us navy#pearl harbor#unsung hero

119 notes

·

View notes

Text

"A few weeks prior, a parade in Boston had already played a deadly part in the pandemic’s spread. In late August, some sailors had reported to sickbay at Boston’s Commonwealth Pier with high fevers, severe joint pain, sharp headaches and debilitating weakness. With stunning speed, illness ricocheted through Boston’s large military population.

Then, on September 3, sailors and civilian navy yard workers marched through the city in Boston’s “Win-the-War-for-Freedom” rally. The next day, the flu had crossed into Cambridge, surfacing at the newly opened Harvard Navy Radio School where 5,000 students were in training. Soon all Boston, surrounding Massachusetts, and eventually most of New England faced an unprecedented medical disaster.

But there was a war to fight. Some of those Boston sailors shipped out to the Philadelphia Naval Yard. Within days of their arrival, 600 men were hospitalized there and two of them died a week before the Philadelphia parade. The next day, it was 14 and then 20 more on the next.

Sailors also carried the virus to New Orleans, Puget Sound Naval Yard in Washington State, the Great Lakes Training Station near Chicago, and to Quebec. The flu followed the fleets and then boarded troop trains. Ports and cities with nearby military installations took some of the hardest hits –underscoring the lethal link between the war and the Spanish flu.

Back in Massachusetts, the flu devastated Camp Devens outside Boston, where 50,000 men were drilling for war. By mid-September, a camp hospital designed for 2,000 patients had 8,000 men in need of treatment. Then the nurses and doctors began to drop. Confounded by this specter, one army doctor observed ominously, “This must be some new kind of infection or plague.”

Few effective treatments for the flu existed. Vaccines and antibiotics would not be developed for decades. The icon of the Spanish flu, the “flu mask” –a gauze facemask required by law in many cities – did almost no good.

Even once the war ended, famously on the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month of 1918, the flu’s devastation did not let up. In spontaneous celebrations marking the armistice, ecstatic Americans jammed city streets to celebrate the end of the “Great War,” Philadelphians again flocked to Broad Street, even though health officials knew that close contact in crowds might set off a new round of influenza cases. And it did.

In April 1919, President Woodrow Wilson fell deathly ill in Paris—he had the flu. “At the moment of physical and nervous exhaustion, Woodrow Wilson was struck by a viral infection that had neurological ramifications,” biographer A. Scott Berg wrote in Wilson. “Generally predictable in his actions, Wilson began blurting unexpected orders.” Never the same after this illness, Wilson would make unexpected concessions during the talks that produced the Versailles Treaty.

The pandemic touched every inhabited continent and remote island on the globe, ultimately killing an estimated 100 million people worldwide and 675,000 Americans –far exceeding the war’s ghastly losses. Few American cities or towns were untouched. But Philadelphia had been one of the hottest of the hot zones.

After his initial failure to prevent the epidemic from exploding, Wilmer Krusen had attempted to address the crisis, largely in vain. He asked the U.S. army to stop drafting local doctors, appropriated funds to hire more medical workers, mobilized the sanitation department to clean the city, and perhaps most important, clear bodies from the street. It was too little too late. On a single October day, 759 people died in the city and more than 12,000 Philadelphians would die in a matter of weeks.

After the epidemic, Philadelphia officially reorganized its public health department, which Krusen continued to lead until he joined the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy and Science, the nation’s oldest pharmacy school. He served as president of the school from 1927 to 1941, before his death in 1943.

As the nation and the world prepare to mark the centennial of the end of “The War to End All Wars” on November 11, there will be parades and public ceremonies highlighting the enormous losses and long-lasting impact of that global conflict. But it will also be a good moment to remember the damaging costs of shortsighted medical decisions shaped by politics during a pandemic that was more deadly than war.

Kenneth C. Davis is the author of More Deadly Than War: The Hidden History of the Spanish Flu and the First World War (Holt), from which this article was adapted, and Don’t Know Much About® History. His website is www.dontknowmuch.com"

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/philadelphia-threw-wwi-parade-gave-thousands-onlookers-flu-180970372/

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

"USS TEXAS (BB-35) arrived at Bremerton, WA Navy Yard drydock on January 14, 1932, and after repairs and new equipment, departed on March 2, 1932. She was put into port at Mare Island Naval Shipyard in Vallejo, the first Navy Yard developed on the Pacific Coast, for supplies, on March 23, cruised south, passing San Clemente and Santa Catalina Islands, into the San Pedro Channel, and returned to her home port of San Pedro, CA on March 28, 1932."

C.A. Moss collection: link

#USS Texas (BB-35)#USS Texas#New York Class#Battleship Texas#Dreadnought#Battleship#Warship#ship#Drydock#Dry Dock#Puget Sound Navy Yard#Puget Sound#Washington#West Coast#January#March#1928#interwar period#my post

72 notes

·

View notes

Photo

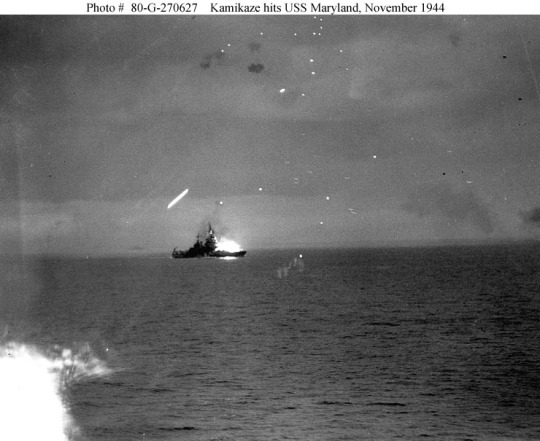

“Bow on view of the USS Maryland (BB-46) sometime after her final refitting at Puget Sound Navy Yard on 21 August 1945 and prior to her decommissioning 3 April 1947.”

(Source)

#Military#History#USS Maryland#Battleship#United States Navy#US Navy#WWII#WW2#Pacific War#World War II

205 notes

·

View notes

Text

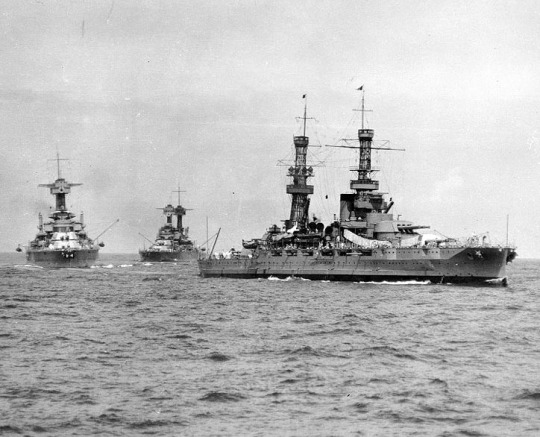

(5/5/1944) USS Maryland (BB-46) Near Puget Sound Navy Yard..USN Image

23 notes

·

View notes

Photo

American women shipbuilders work as rivet heaters and passers at the Puget Sound Navy Yard, Washington. May 29, 1919. #internationalworkersday #vintagedenim #vintageworkwear #vintageoveralls #overalls #coveralls #denim #chorejacket #hat #cap #ww1 #1919 #vintagestyle #womenswear #vintagewomenswear #union #rights #womensstyle #ruggedstyle #borrowedfromtheboys #vintagephoto https://www.instagram.com/p/B_qVHLxDrlJ/?igshid=bsazbq0rjbtj

#internationalworkersday#vintagedenim#vintageworkwear#vintageoveralls#overalls#coveralls#denim#chorejacket#hat#cap#ww1#1919#vintagestyle#womenswear#vintagewomenswear#union#rights#womensstyle#ruggedstyle#borrowedfromtheboys#vintagephoto

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Photograph of Women Rivet Heaters at Puget Sound Navy Yard,” 5/29/1919

Series: General Photographic File, 1893 - 1945. Record Group 86: Records of the Women's Bureau, 1892 - 1995.

Women riveters pose for the camera at the Navy Yard in Puget Sound, Washington. Taken a generation before the more famous World War II image of “Rosie the Riveter,” this photograph shows women working in industrial jobs traditionally filled by men, just as women did during World War II.

Uncover more World War I Centennial Resources at the National Archives.

via DocsTeach

#World War I#WWI#WWI100#Rosie the Riveter#Puget Sound Washington#Puget Sound#Washington#women at work#women's history#industrial job#industry#archivesgov#May 29#1919#1900s#1910s

201 notes

·

View notes

Text

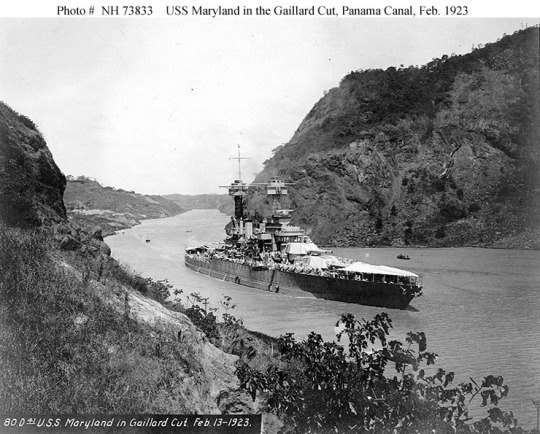

USS Maryland (BB-46)

Maryland was a Colorado-class battleship commissioned in 1921. Following her commissioning, Maryland undertook an East Coast shakedown cruise. Shortly thereafter, Maryland was made flagship of Admiral Hilary P. Jones. Maryland found herself in great demand for special occasions. She appeared at Annapolis, Maryland, for the 1922 United States Naval Academy graduation and at Boston, Massachusetts, for the anniversary of the battle of Bunker Hill and the Fourth of July.

From 18 August to 25 September, she paid her first visit to a foreign port transporting Secretary of State Charles Evans Hughes to Rio de Janeiro for Brazil's Centennial Exposition. The next year, after fleet exercises off the Panama Canal Zone, Maryland transited the canal in the latter part of June to join the battle fleet stationed on the west coast. She continued to be a flagship until 1923 when the flag was shifted to Pennsylvania.

She made another voyage to a foreign port in 1925, this time to Australia and New Zealand. Several years later, in 1928, she transported President-elect Herbert Hoover on the Pacific leg of his tour of Latin America. She was overhauled in 1928–1929, and the eight 3-inch anti-aircraft guns were replaced by eight 5-inch/25 cal guns. Throughout these years and the 1930s, she served as a mainstay of fleet readiness through tireless training operations. She conducted numerous patrols in the 1930s.

In 1940, Maryland and the other battleships of the battle force changed their bases of operations to Pearl Harbor. She was present at Battleship Row along Ford Island during the Japanese attack on 7 December 1941.

On the morning of 7 December, Maryland was moored along Ford Island, with Oklahoma to port, connected by lines and a gangway. To her fore was California, while Tennessee and West Virginia were astern. Further aft were Nevada and Arizona. The seven battleships, in what is now known as "Battleship Row," had recently returned from maneuvers. Many of Maryland's crew were preparing for shore leave at 09:00 or eating breakfast when the Japanese attack began. As the first Japanese aircraft appeared and explosions rocked the outboard battleships, Maryland's bugler blew general quarters.

Seaman Leslie Short—addressing Christmas cards near his machine gun—brought the first of his ship's guns into play, shooting down one of two torpedo bombers that had just released against Oklahoma. Inboard of Oklahoma, and thus protected from the initial torpedo attack, Maryland managed to bring all her antiaircraft (AA) batteries into action. The devastating initial attack sank Oklahoma, and she capsized quickly, with many of her surviving men climbing aboard Maryland to assist her with anti-aircraft defenses.

Maryland was struck by two armor-piercing bombs which detonated low on her hull. The first struck the forecastle awning and made a hole about 12 ft (3.7 m) by 20 ft (6.1 m). The second exploded after entering the hull at the 22 ft (6.7 m) water level at Frame 10. The latter hit caused flooding and increased the draft forward by 5 ft (1.5 m). Maryland continued to fire and, after the attack, sent firefighting parties to assist her compatriots, especially attempting to rescue survivors from the capsized Oklahoma. The men continued to muster the AA defenses in case the Japanese returned to attack. In all, two officers and two men were killed in the attack.

The Japanese erroneously announced that Maryland had been sunk, but on 30 December, the damaged ship entered Puget Sound Navy Yard for repairs just behind Tennessee. Two of the original twelve 5 -inch/51 cal guns were removed and the 5-inch/25 cal guns were replaced by an equal number of 5-inch/38 cal dual purpose guns. Over the course of the next two months, she was repaired and overhauled, receiving new fighting equipment. Repairs were complete on 26 February 1942. She then underwent a series of shakedown cruises to West Coast ports and the Christmas Islands. She was sent back into action in June 1942, the first ship damaged at Pearl Harbor to return to duty.

During the important Battle of Midway, Maryland played a supporting role. Like the other older battleships, she was not fast enough to accompany the aircraft carriers, so she operated with a backup fleet protecting the West Coast. Maryland stood by on security, awaiting call from other ships if she was needed, until the end of the battle. At the end of the action around Midway, Maryland was sent to San Francisco.

Thereafter, Maryland engaged in almost constant training exercises with Battleship Division 2, Battleship Division 3, and Battleship Division 4 until 1 August, when she returned to Pearl Harbor for repairs, her first time in the harbor since the Japanese attack. She departed Pearl Harbor in early November with Colorado, bound for the forward area. On 12 November, the pig mascot King Neptune came aboard Maryland to initiate her "pollywogs" for the line-crossing ceremony. Maryland steamed for the Fiji Islands where she patrolled against Japanese incursion. The two battleships acted as sentinels to guard against Japanese advance to prevent Japanese forces from threatening Australia. During this duty, the two battleships conducted frequent sweeps for Japanese forces.

In early 1943, with the success of the Solomon Islands campaign, Allied forces went on the offensive. In February 1943, Maryland and Colorado moved to New Hebrides, operating off of Efate.[11] Intense heat there proved difficult and unpleasant for the crew. She then moved to Espiritu Santo to guard against Japanese incursion, but heat and heavy rains plagued this tour of duty.[10] Maryland and Colorado stood out of Aore Island Harbor in August. During a five-week overhaul at Pearl Harbor's shipyard, several 40 millimetres (1.6 in) AA guns were installed on the top decks and foremast as protection against anticipated Japanese air raids in future operations.

Departing the Hawaiian Islands on 20 October 1943 for the South Pacific, Maryland became flagship for Rear Admiral Harry W. Hill's V Amphibious Force and Southern Attack Force in the Gilbert Islands Invasion. Also aboard her were Major General Julian C. Smith, commander of 2nd Marine Division, General "Howling Mad" Smith, commander of the Marine landing forces, and Colonel Evans Carlson, commander of Carlson's Raiders. Maryland returned to Efate Island staging area, where she joined a large task force preparing for an assault on Tarawa.

The battle of Tarawa commenced on 20 November. In her first offensive action of the war, Maryland's guns opened fire at 05:00, destroying a shore battery with five salvos on the southwestern point of Betio Island in the Tarawa Atoll. At 06:00 she commenced a scheduled shore bombardment to soften up Japanese defenses ahead of the landings. Maryland moved closer to shore to attract Japanese fire and locate artillery emplacements, in the process raking Japanese gun emplacements, control stations, pillboxes and any Japanese installations she could spot. At 09:00 as Marine landing forces encountered heavy Japanese resistance and began taking casualties to emplaced crossfire, Maryland provided covering fire to eliminate several Japanese machine gun nests. Her scouting plane then began to cover the progress of the Marines' assault, with Maryland providing artillery support. The plane was damaged and pilot wounded in this action.

After three days of covering the offensive on Betio Island, she moved to Apamama Island to guard Marine landings there. Marines met with only light resistance from 30 Japanese soldiers there, and two prisoners were brought to Maryland. On 7 December, Maryland left Apamama Island for Pearl Harbor. After a brief stopover there, Maryland left for San Francisco for repairs.

Maryland steamed from San Pedro, California on 13 January 1944, rendezvoused with Task Force 53 at Lahaina Roads for two days of loading ammunition, refueling, and provisioning ahead of a new operation supporting the Marshall Islands campaign. On 30 January 1944, she moved to support landings on Roi Island, along with Santa Fe, Biloxi, and Indianapolis, which formed the Northern Support Group of TF 35.

In the predawn hours of 31 January, the ships began a bombardment of Kwajalein Atoll, the opening moves of the battle of Kwajalein. Maryland destroyed numerous Japanese stationary guns and pillboxes. In the course of the battle, she fired so much that she split the liners in the guns of Turret No. 1, putting it out of action for the rest of the day. On 1 February, she continued her attack on Japanese positions as the U.S. landing forces advanced. She became the flagship for Admiral Connally for the next two weeks, resupplying and refueling many of the smaller ships in the operation until she departed with a task unit of carriers and destroyers on 15 February 1944, steaming for Bremerton Navy Yard, where she underwent another overhaul, with her guns being replaced.

Two months later, Maryland sailed westward on 5 May, joining Task Force 52 headed for Saipan. Vice Admiral Richmond K. Turner allotted TF 52 three days to soften up the island's defenses ahead of the assault. Firing commenced at 05:45 on 14 June. They quickly destroyed two coastal guns, then began bombarding Garapan, destroying ammunition dumps, gun positions, small boats, storage tanks, blockhouses and buildings. She then turned her guns to Tanapag, leveling it in heavy bombardment. The invasion commenced 15 June, and Maryland provided fire support for the landing forces.

The Japanese attempted to counter the battleships through the air. On 18 June, the ship's guns shot down their first Japanese aircraft, but on 22 June, a Mitsubishi G4M3 "Betty" medium bomber flew low over the still-contested Saipan hills and found Maryland and Pennsylvania. The Japanese plane dropped a torpedo, opening a large hole in Maryland's starboard bow. The attack caused light casualties, and in 15 minutes she was underway for Eniwetok, and from there she steamed for the repair yards at Pearl Harbor (in reverse the whole time so as not to do further damage to her bow), escorted by two destroyers. Two men were killed in the attack.

With an around-the-clock effort by the shipyard workers, Maryland was repaired in 34 days, departing on 13 August. She then embarked for the Solomon Islands with a large task force, anchoring in Purvis Bay off Florida Island for two weeks before steaming for the Palau Islands on 6 September. She then joined Rear Admiral Jesse B. Oldendorf's Western Fire Support Group. Firing first on 12 September to cover minesweeping operations and underwater demolition teams at the opening of the Battle of Peleliu, Maryland again conducted shore bombardment supporting the landing craft as they approached the beaches on 15 September. Four days later, organized resistance collapsed, permitting the fire support ships to retire to the Admiralty Islands at the end of the month.

Maryland steamed for Seeadler Harbor, Manus where she was assigned to the 7th Fleet under Admiral Kinkaid. The fleet sortied 12 October, and Maryland joined Task Group 77.2, which was the gunfire and covering force for the invasion of Leyte. She, along with four other battleships and numerous cruisers and destroyers, steamed into Leyte Gulf on the morning of 18 October. Maryland took position between Red and White Beaches and began bombarding them ahead of the invasion, which began at 10:00 20 October. Securing the beaches quickly, Maryland then took up a sentinel position in Leyte Gulf to guard the beaches against Japanese counterattack by sea.

For the next several days, Japanese forces launched air raids to counter the incursion. These included the first widespread use of the kamikaze suicide attack. Several days later, U.S. submarines in the South China Sea spotted two Japanese forces on approach: five battleships steaming toward San Bernardino Strait, and another force of four Japanese carriers in northern Luzon.

On 24 October, Maryland, West Virginia, Mississippi, Tennessee, California, and Pennsylvania sailed to the southern end of Leyte Gulf to protect Surigao Strait with several cruisers, destroyers, and PT Boats. Early on 25 October, during the Battle of Surigao Strait, Japanese battleships Fusō and Yamashiro, with their screens, led the Japanese advance into the Strait. At 03:55, the waiting Americans ships launched an ambush of the two Japanese battleships, pounding them with torpedoes and main guns. Torpedoes from the destroyers sunk Fusō. Continued attacks by the task force also claimed Yamashiro. A few of the remaining Japanese ships then fled to the Mindanao Sea, pursued by Allied aircraft.

Following the victory, Maryland patrolled the southern approaches to Surigao Strait until 29 October; she then steamed for the Admiralty Isles for brief replenishment and resumed patrol duty around Leyte on 16 November, protecting the landing forces from continued Japanese air attacks. On 29 November, during another Japanese air attack, a kamikaze aircraft surprised and struck Maryland. The aircraft crashed into Maryland between Turrets No. 1 and 2, piercing the forecastle, main, and armored decks and blowing a hole in the 4-inch steel, causing extensive damage and starting fires. In all, 31 men were killed and 30 wounded in the attack, and the medical department was destroyed but still functional.

The battleship continued her patrols until relieved on 2 December, when she sailed with two heavily damaged destroyers for repairs. She reached Pearl Harbor on 18 December, and was extensively repaired and refitted over the next couple of months.

After refresher training, Maryland headed for the western Pacific on 4 March 1945, arriving Ulithi on 16 March. There she joined the 5th Fleet and Rear Admiral Morton Deyo's Task Force 54 (TF 54), which was preparing for the invasion of Okinawa. The fleet departed on 21 March, bound for Okinawa.

Maryland was assigned targets on the southern coast of Okinawa to support a diversionary landing, which would distract Japanese forces away from the main landing on the west coast. Japanese forces responded with several air raids, with two of Maryland's radar picket destroyers being struck by kamikaze planes, with Luce sinking. On 3 April, she was moved to the west coast invasion beaches to assist Minneapolis in destroying several shore batteries. Following the land invasion, she remained with the support force off Bolo Point providing artillery support for the invading troops.

Maryland continued fire support duty until 7 April, when she steamed north to intercept a Japanese surface force with TF 54. The Japanese ships, including the Yamato, came under constant U.S. air attacks that day, and planes of the Fast Carrier Task Force sank six of the 10 ships in the force. At dusk, a kamikaze loaded with a 551 lb (250 kg) bomb crashed the top of Turret No. 3 from starboard. The explosion wiped out the 20 mm mounts and caused a large fire. The 20mm ammunition ignited from the heat, causing further casualties. In all, 10 were killed, 37 injured and 6 missing following this attack. Maryland remained on station for the next week and continued her artillery support mission through several more air raids. Turret No. 3, damaged but usable, remained silent for the remainder of this mission.

On 14 April, Maryland left the firing line at Okinawa and escorted several retiring transports. They steamed via the Mariana Islands and Guam to Pearl Harbor, and she reached the Puget Sound Navy Yard at Bremerton on 7 May for extensive overhaul. All of her 5 in guns were removed and replaced by sixteen 5 inch/38 cal guns in new twin mounts. Turret No. 3 was repaired and the crew quarters were improved. She completed repairs in August, leaving for tests and training runs just as Japan surrendered, ending the war.

She next entered Operation Magic Carpet fleet. During the remaining months of 1945, Maryland made five voyages between the west coast and Pearl Harbor, returning more than 8,000 servicemen to the United States.

Arriving at Seattle, Washington on 17 December, Maryland completed her Operation Magic Carpet duty. She entered Puget Sound Naval Shipyard on 15 April 1946, and was placed in commission in inactive reserve on 16 July. She was decommissioned at Bremerton on 3 April 1947, and remained there as a unit of the Pacific Reserve Fleet. Maryland was sold for scrapping to Learner Company of Oakland, California on 8 July 1959.

On 2 June 1961, Governor of Maryland J. Millard Tawes, dedicated a monument to the memory of Maryland and her men. Built of granite and bronze and incorporating the bell of "Fighting Mary", this monument is located on the grounds of the State House in Annapolis.

174 notes

·

View notes