#puyi

Text

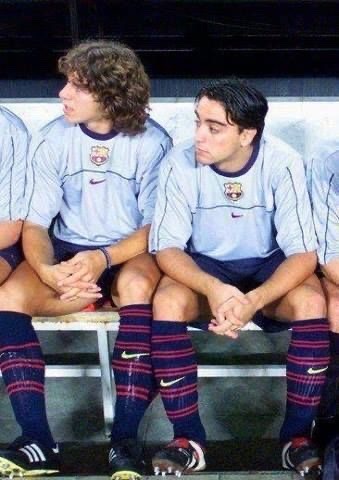

Carles Puyol & Xavi Hernández

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

🥹🥹🥹

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The last emperor, 1987

#biography#drama#history#the last emperor#bernardo bertolucci#enzo ungari#mark peploe#puyi#aisin-gioro pu yi#peter o'toole#john lone#farewell

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Ryuichi Sakamoto's main theme for "The Last Emperor" (Bernardo Bertolucci).

#ryuichi sakamoto#ryuichi#sakamoto#the last emperor#china#bernardo bertolucci#puyi#film music#soundtrack#soundtracks#film score#movie music#film composer#composer#composers#orchestra#music#musician#musicians#movie#movies#film#films#Youtube

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Last Emperor (Movie Review) | An Informative Historical Drama

36 years ago this week the epic portrayal of an Emperor, a citizen's life graced our screen and here's my review of The Last Emperor

#TheLastEmperor #ThrowbackThursday #MovieReview

Bernardo Bertolucci (Director), Puyi (Novel)CASTJohn LoneJoan ChenPeter O’TooleYing RuochengVictor WongDennis DunVivian WuRyuichi SakamotoBased on From Emperor to Citizen, The Autobiography of Aisin-Gioro Pu Yi by Puyi

Review

I’ve been aware of this movie for a long time but only recently saw it when one of my local movie theatre put it back on the big screen. This Academy Awards winning…

View On WordPress

#Based on a book#Based on a novel#Bernado Bertolucci#Biography#Book adaptation#Book to Film#Book to Movie#Cary-Hiroyuki Tagawa#Dennis Dun#Drama#Enzo Ungari#Fumihiko Ikeda#Garcwrites#Guang Fan#Henry Kyi#history#Jade Go#Joan Chen#John Lone#Maggie Han#Mark Peploe#movie adaptation#movie lovers#movie review#movies#peter o&039;toole#Puyi#Review#Ric Young#Richard Vuu

0 notes

Text

on the throne

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Text

get really emotional whenever puyol posts himself watching barca games on ig like that’s my capi i miss him 😭😭😭

1 note

·

View note

Text

2010: From a Russian Perspective: History of PRC intelligence

Chapter 1 History of the Special Services of Communist China (book excerpt)

Interesting perspective based partially on Russian sources. Not necessarily entirely accurate as for example the reference to Hua Guofeng as one of the “Gang of Four”.

Glazunov’s 2010 book can be downloaded for 70 rubles.

The Chinese Threat

Китайская разведка

О. N. Glazunov

Only now are we beginning to see Red…

View On WordPress

#China#Chinese#Communist Party#defector#Intelligence#KGB#Lin Biao#Ministry of Public Security#MPS#MSS#PRC#Puyi#Russian#Soviet#spy#USSR#共产党#中国

0 notes

Text

“The nation of Manchukuo was theoretically founded on a complex and fairly contradictory mix of principles, leaving the role of law in the new society somewhat unclear. At its most basic level, the creation of an independent Manchukuo was represented as a triumph of popular sovereignty, the “unanimous will of the thirty million people of Manchuria and Mongolia,” a portrayal that fit well with Wilsonian ideals of democratic self-determination. For many, such claims rang hollow even at the outset and appeared to be aimed largely at convincing Western powers of the legitimacy of the new state. But they do imply a degree of affinity for the dressings, if not the genuine ideals of liberal government, of which the rule of law under a free and independent judiciary would be paramount.

At the same time, even if the foundation of Manchukuo theoretically represented an act of popular will, it was still very much a created society. Japanese superiority was never in doubt. The rhetoric of statehood aside, the paternalistic attitude that Japan took toward nominally independent Manchukuo made it difficult to distinguish from a colony. This was not simply a matter of Japanese duplicity; many of the Chinese intellectuals who would take up positions in the Manchukuo government had openly argued that China would benefit from a period of foreign stewardship. As was the case in Taiwan and Korea, the institution and reform of law in Manchukuo was part of a package of civilizing methods imposed from above and from without, constructing a society while protecting a privileged place for Japanese citizens and interests therein.

Tension between these ideals was further complicated by the rhetoric of what made Manchukuo unique. In its own propaganda, Manchukuo was not merely independent. It was a radically new and uniquely Asian form of polity, an incarnation of Japanese spiritualism taking root in a multi-ethnic state, and thus, even more than Japan itself, an exemplar for the political future of pan-Asianism. What role should law play in a country ruled by this unlikely mix of Asian morality and hyper-modernism, legitimized in terms of Western liberalism, yet openly disdainful of it?

Given the somewhat schizophrenic ideals officially espoused in its founding, it is not surprising to see law in Manchukuo represented in a number of strikingly different ways. Manchukuo was established amid a heavy dose of legal rhetoric, and some of the first acts taken after its founding were legal in nature. These included an appeal to the principles of international law to assure the legitimacy of the new state and promises to create a legal system in order to “protect the livelihood of the people, and increase their wealth and stability.” At the core of this new system, the 1932 Organic Law (Law of the Organization of the State of Manchukuo, Manshu koku no seiji soshiki ho) outlined the structure of government and included a twelve-part Human Rights Protection Law. On its face, the government structure appeared designed to balance power between legislative bodies and the executive branch. To ensure the independence of the courts, the judiciary was to be a distinct branch of government, judges were appointed for life, and all judicial organs were financially under the central government so as to avoid the corruption that had supposedly characterized the previous justice system.

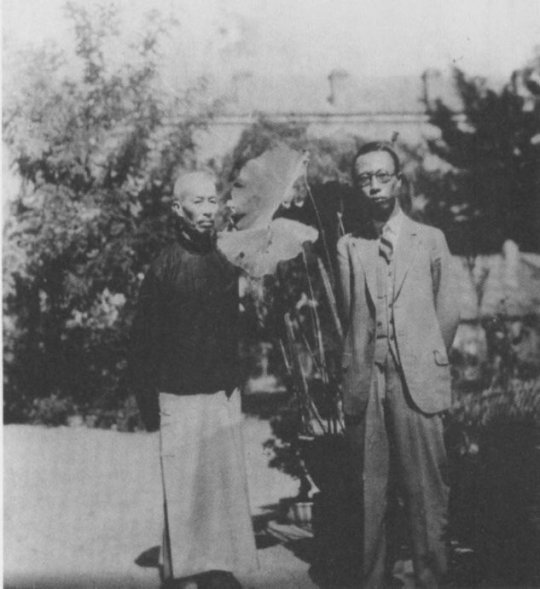

Despite the appearance of balance within the government, the entire state structure rested on the foundation of an external, spiritualist authority. Even if the state was founded on the principles of popular will, it did not serve this will through elected representation, but rather through a spiritual bond between the state and people known as the “Kingly Way” (wangdao). The theory of the Kingly Way was largely the personal project of Zheng Xiaoxu (1860–1938), a former official of the Qing empire, constant companion of the deposed emperor Pu Yi during the 1920s, and first prime minister of Manchukuo. It represented an attempt to meld the rhetoric of Confucian moral governance with the machinery of a modern state, thus creating the foundation of a new Asian polity. In all of its public pronouncements, the new state emphasized this spiritual core, voiced alternately as the Kingly Way or later as the equally vague “spirit of national foundation” (jianguo jingshen). The short declaration establishing the government of Manchukuo, uttered by the titular head of state (although not yet emperor) Pu Yi on March 9, 1932, is typical of the moral rhetoric of Manchukuo:

Humankind must value morality. Yet there is a difference between races—in which some control others while praising themselves. Such morality is very thin. Humankind must value benevolence and love. Yet there is war between nations—in which people seek to profit from other’s loss. Such benevolence and love is very thin. Our Nation has been founded on morality, benevolence and love. When racial difference and international war have been eradicated, we will see the establishment of a true paradise of the Kingly Way. The citizens of Our Nation must devote themselves to this task.

Such statements are interesting not only for their somewhat saccharine portrayal of the new state, but equally so for what they do not mention. While these pronouncements emphasize the spiritual renaissance of the Kingly Way, they generally lack reference to law, procedure, or efficiency. Even those portrayals, such as the Declaration of Manchukuo Statehood (Manshu koku kenkoku sengen), that justify the creation of the new state in terms of popular welfare, criticizing the old regime as incompetent, corrupt, and thus unable to protect the people against the twin evils of Communism and banditry, do not speak of the new state in terms of the restoration of law and order as much as this new, moral attitude toward governance.

Above: Zheng Xiaoxu and Puyi in the 1930s

This is not to say that the new state was hostile to law, but rather that law was portrayed as an expression of the same spontaneous sentiment that had created independent Manchukuo. As such, law was depicted as consensual, an expression of values and purpose held in common by state and citizens. Despite its name, the Human Rights Protection Law clearly subjected individual interests to the needs of state. There was no question of this or any other law serving to safeguard the rights of individuals against the state, the idea of any such antagonism being viewed as a leftover of individualistic bourgeois liberalism. In Manchukuo, this was portrayed as Asian consensus culture reasserting itself against selfish Westernism. But the claim that “the people” are of one mind with the government and its institutions are common to totalitarian states.

The rhetoric of morality permeated official discourse in Manchukuo, and within it, law was treated primarily as a practical measure. Although many schools of Chinese philosophy had traditionally disdained law as corrosive of public morality, in Manchukuo it was invoked as a means to attaining the moral ends of good governance. However, even if the balanced structure of the Manchukuo government was put into place in order to maintain oversight of “government morality” (seiji dotoku), the nature of this moral end was often left unclear. Occasionally it was represented in terms of economic good. The Human Rights Protection Law itself includes the commitment of the government to protect citizens against usurious interest rates, or any other form of “improper economic oppression.” However, hostility to anything resembling Sun Yat-sen’s political doctrine of the “Three Peoples’ Principles” (which included a provision for “Peoples’ Livelihood”) and an intense paranoia over the advance of Communism ensured that this type of economic rhetoric would always remain somewhat muted.

More often it was represented in terms of the spiritual and moral destiny of the state, and later of the Japanese Empire. Through the rhetoric of the Kingly Way, the emperor was held up as the concrete expression of the spiritual foundation of the new state from which all political and moral authority proceeded. Closing a long essay on the history of Manchuria, Japanese army captain Okada Meitaro waxed poetic about how under the guidance of the emperor, the ruler and people were one (kunmin ikka). Interpreting this often-repeated formulation to include the state would not be precisely accurate. The spiritual bond was that between the people and the emperor himself; the state and its institutions were necessary only as they were practical. The law itself was not inviolable because, according to the somewhat vexing logic of one source, “from the legal standpoint, the Emperor is the source of all authority.” While the rhetoric of imperial divinity would take on a much greater significance during the 1940s, even in this earlier period, the division between the emperor and government mirrored that between the moral basis of the state and its everyday procedural concerns. At a fundamental level, the law of Manchukuo was a celebration of this same consensus, a concrete expression of social harmony and universally held values, and only secondarily a tool of practical governance.

At the same time, the appeal to law was important for legitimating Manchukuo in the eyes of the outside world. In a general sense, possession of a modern legal code was held up as a hallmark of an advanced civilization, a designation that Japan itself had worked long and hard to attain. Over the previous decades, attention to international criticism had motivated not only the revision of criminal procedure inside Japan, but also the laborious attempt made to justify events such as the annexation of Korea not simply by force of arms, but within the letter of international law.

The most prized mark of Japan’s entry into the family of “civilized nations,” and the standard for which they fought tirelessly in Manchukuo, was revision of extraterritoriality. This provision was introduced by many Western powers in their treaties with China and Japan (and later by Japan in China and Korea) and allowed the former to try its own citizens for offenses committed within the territory of the latter, on the grounds that Asian judicial systems were excessively violent and unreliable. For western-oriented reformers in Meiji Japan, such a characterization had been particularly grating, and with the help of European advisors, Japan had managed to reform its code to secure abrogation of extraterritoriality by the late nineteenth century. It now faced a similar battle in Manchukuo by virtue of preexisting treaty obligations on what had previously been Chinese soil.

However, the decision for Manchukuo to honor extraterritoriality clauses in existing treaties was made voluntarily by Japan. It was motivated by two considerations, the desire to court Western approval for the new state and, more fundamentally, the need to maintain the special rights enjoyed by Japanese commercial interests (particularly in the semi-colonial territories administered by the South Manchuria Railway) and citizens until a judicial system tailored to Japan’s liking had been established. As such, the road to ending extraterritoriality turned around two somewhat contradictory principles: the manipulation of the Manchukuo judicial system to enshrine special rights for Japan and the courting of other extraterritorial powers (all Western) to recognize these changes as reforms and voluntarily surrender their own rights.

The high profile of this emotional issue is seen in the amount of attention it received in legal circles in Manchukuo and Japan. In December 1933, a joint conference of thirty-six Japanese and native officials of Manchukuo convened in the city of Fengtian to discuss the legal basis of Japanese abrogation of extraterritoriality. This was followed by a series of similar meetings in 1934 and 1935. Nor was the attention to this question restricted to Manchukuo; these meetings were widely publicized within Japan, in no small part to mollify fears among domestic investors and settlers over a potential loss of Japanese privileges in Manchuria.

In an allied effort, the new government immediately began taking steps to promulgate a constitution. Diplomats observing the new state had expected such a step to be taken immediately and, through 1936, were promised the immanent release of a Manchukuo constitution. They were somewhat mollified by the promulgation of the Organic Law in 1932, which was then revised in 1934 to reflect the accession of Pu Yi to emperor. The delay in promulgating the actual constitution was a surprise to observers, many of whom were already convinced that this would be nothing more than a cosmetic document, imposed by Japan with little debate or controversy.

Yet controversy there was, because the constitution of Manchukuo could potentially establish precedents that would influence the entire empire, including Japan itself. Although legal scholar Mitani Takeshi characterized the Manchukuo Constitution as an imperfect copy of the 1889 Meiji Constitution, the structure of government outlined in the 1932 Law of the Organization of the State of Manchukuo was in fact adapted largely from the Republic of China. This was primarily to ensure a smooth transition between the two governments, but also because Chinese and Japanese jurists and jurisprudence were already quite close. Indeed, the Chinese government structure and legal codes as they appeared in the 1930s had themselves been very heavily influenced by Japanese advisors a generation earlier.

Nevertheless, small but revealing differences separated Manchukuo from both China and Japan. Like that of the Republic of China, the government of Manchukuo was divided into Legislative, Judicial, Cabinet and Oversight Yuan, the latter omitting the Examination Yuan. Other differences were more fundamental. While the both the Chinese Legislative Yuan and the Japanese Imperial Diet had the power to propose, pass, and veto laws, the Legislative Yuan of Manchukuo was restricted to assisting (yokusan) in this function. The Manchukuo Legislative Yuan did have the power to reject laws, but this rejection was not binding and could easily be overturned. In theory, this was because the Manchukuo legislature was not an expression of popular will, but rather of imperial benevolence, and served at the convenience of the emperor. According to Mitani, it also reflected the image that some had for the future of Japan, with power centralized at the expense of a severely weakened Imperial Diet. Given its lack of any real power, it was very difficult to find recruits for this body; British consular reports paint a rather sad picture of the 1934 Manchukuo legislature as thirty-nine “more or less reluctant nominees of Japan.”

- Thomas David Dubois, “Rule of Law in a Brave New Empire: Legal Rhetoric and Practice in Manchukuo,” Law and History Review Summer 2008, Vol. 26, No. 2: p. 291-298.

#manchukuo#manchuria#state of manchuria#滿洲國#ᠮᠠᠨᠵᡠ ᡤᡠᡵᡠᠨ#legal code#empire of law#history of crime and punishment#constitutional government#puyi#governmental law#chinese history#empire of japan#jurisprudence#academic quote

0 notes

Text

Production Notes — Background

Bernardo Bertolucci's THE LAST EMPEROR was filmed entirely on location in China in 1986. Bertolucci and his producer Jeremy Thomas were the first Western filmmakers to be allowed to make a film about modern China and it took two years of complex negotiations to obtain the unprecedented permissions which also allowed them to film in hitherto forbidden locations.

On August 4th, 1986, in the Chinese capital Beijing (formerly Peking), the cameras finally rolled on one of the biggest and most ambitious films ever made.

The independently financed production is an epic tale which embraces the entire sweep of twentieth century China and the years of the most tumultuous changes the country has ever seen.

Yet despite its cast of thousands, Itys palatial and exotic locations, its sumptuous design film is also the intimate story of an extraordinary and unique man and his journey of self- discovery, a man who started life as the ruler of half the world's population and ended it as a humble gardener in Peking.

Bertolucci was fascinated by the life of the ex-Emperor and the question which became the heart of his film -can a man change? Did Pu Yi change and if so, how much during the years of his re-education in prison?

"Pu Yi's story can be described in many ways," says Bertolucci. "As a journey from darkness to light or as the Chinese say, changes from a dragon to a normal person, from an Emperor to citizen.

Pu Yi, the last emperor, came to the Imperial throne in 1908 at the age of 3, the Son of Heaven, Lord of Ten Thousand Years, was forced to abdicate at the age of six, was thrown out of the Forbidden City in 1924 with his two wives and drawn into the life of a Western-style playboy. In 1931, he succumbed to the seductive Japanese invitation to mount the throne again and became a puppet emperor in the Japanese controlled state of Manchukuo. Captured by the Russians in 1945, he was returned to China in 1950, expecting to be executed by the communists. Instead, he spent ten years in gaol in the hands of an enlightened prison governor and emerged a changed man. He returned to Peking at the start of the Cultural Revolution and became a gardener, more free than he had ever been before. He died in 1967.

John Lone stars as Pu Yi, Joan Chen as the Empress Wan Jung, and Peter O'Toole as Reginald Johnston, the emperor's tutor. The Director of Photography is two-time Oscar winner, Vittorio Storaro, Production Designer is Ferdinando Scarfiotti and Costume Designer is James Acheson. The screenplay is written by Mark Peploe with Bernardo Bertolucci. Jeremy Thomas is the producer.

In March 1984, Bernardo Bertolucci and Mark Peploe first visited China with proposals for two films. One of them was "From Emperor to Citizen," the autobiography of Pu-Yi which Bertolucci has recently read. The Chinese response was warm and immediate - they welcomed the idea of a Western director filming the story of the last emperor of China.

The filmmakers were pleasantly surprised by the lack of restraints imposed by the Chinese. Although negotiations were long and complex, due to complications inherent in the meeting of two different cultures, the Chinese gave THE LAST EMPEROR unlimited cooperation through the Cinema Film Co-Production Corporation in exchange for the Chinese distribution rights to the film. They approved the script, commenting only on factual inaccuracies and demanding no alterations.

Pu-Yi’s eldest surviving brother, Pu Chieh and Li Wenda who helped Pu-Yi to write his autobiography, acted as official advisers on the film. In unofficial capacities, there were also many other survivors of the period who were tracked down by the production, including Jin Yuan, the prison governor, and Big Li, the manservant.

The logistics of the production were staggering. THE LAST EMPEROR brought together people from six nations. Actors came from America, Great Britain, China, Hong Kong, and Japan to play the 60 main characters in the story, 100 technicians from Italy, 20 from Britain and 150 Chinese worked for 6 months of shooting to put the film on the screen and 19,000 extras, including soldiers of the People's Liberation Army, appear altogether in the immense crowd scenes.

Costume designer lames Acheson gathered 9,000 costumers from all over the world. Imperial Aunt so the wonders and peasants, Japanese army uniforms, Kuomintang uniforms and western dresses fashionable in the Twenties and Thirties were among the many that were bought or made in China and cities as far apart as London, Hong Kong, Tokyo, Rome, Spoleto in Italy, and Brighton in England.

The inner man had to be catered for as well. An Italian chef wa brought from Rome and with him came 220 kilos of Italian mineral water, 200 kilos of Italian coffee, 500 litres of olive oil and 2,000 kilos of pasta.

Twenty vintage cars, including Delages, Ford Model T's, Fiats, Lancias, Buicks, Hispano Suizas and Mercedes limousines, plus motorcycles with side cars and a child's bicycle for the young Emperor, were shipped by sea to China to appear in the film.

The production spent four months in China on location in Beijing, Dalian and Changchun in Manchuria with interiors completed over two months at Cinecittà Studios in Rome.

Many weeks were devoted to filming inside the Forbidden City, home for so many years to the ruling dynasties of China. Bertolucci describes it as "the set Hollywood dare not build, the Disneyland of China". The Forbidden City is one of the most impressive sights anywhere in the word. It stands in the heart of Peking, its 250 acres entirely enclosed by high red walls, some of them 50-feet thick. It has 9,999 rooms (the Chinese believed that only heaven had 10,000 rooms) built around a bewildering jigsaw of courtyards, alleys, and gardens. Here Pu-Yi spent 16 years of his life, unable to go outside, surrounded by thousands of eunuchs and the ladies of the court. Forbidden no longer, it is now one of China's greatest tourist attractions swallowing up over 50,000 visitors a day. During filming, whole palaces and courtyards were closed off for the production as curious tourists gathered in their thousands to watch.

In Beijing, the production was based at the Beijing Film Studios where 1,200 Chinese normally eat, sleep and work according to the Chinese system of belonging to a work unit that also houses and feeds you. The studios normally produce 15-18 feature movies while LAST EMPEROR was shooting, most other activity stopped as all available studio space was given over to the mammoth production.

Here production designer Ferdinando Scafiotti designed and built a number of sets including the Empress Dowager’s bedchamber and the emperor’s living quarters.

Exterior sets included a thronging ancient Peking Street scene, the Emperor's father's house and the Fushun prison yard. So sturdy was the house and its courtyard, built by the Chinese in brick and stone, that after filming it was immediately turned into living quarters for the studio workers.

China is a country in the throes of remarkable changes that are transforming it almost in front of the visitor's eyes.

"My film resembles China because its story is also about change,” says Bertolucci.

"All my previous films were journeys from light towards darkness. THE LAST EMPEROR goes the opposite way, from darkness to light.”

The Director: Bernardo Bertolucci

BERNARDO BERTOLUCCI was born in Parma, Italy in 1941. Through his father Attilio Bertolucci, a well-known pol, he met the director Pier Paolo Pasolini and in 1961 abandoned his course in modern literature to work as an assistant director on Pasolini's first film "Accatone."

The following year, Bertolucci published "In Cerca del Mistero,” a collection of poems which was awarded Italy's prestigious Viareggio Opera Prima Prize and wrote the screenplay of the film, which was to be his first as a director, “Commare Secca" (The Grim Reaper). The film was well received at the Venice Film Festival and Bertolucci went on to make his second feature, “Before the Revolution.”

Bertolucci then had to endure the frustration of not being able to raise the finance lo make a Feature film, making a series of documentaries and writing screenplays culminating in directing.

"The Conformist", his brilliant adaptation of the Alberto Moravia novel, which firmly established his reputation as a major figure in contemporary cinema.

1973 was the year of "Last Tango in Paris", which inspired Pauline Kael of the New Yorker 10 liken the first screening of the film to the riotous first night of the 1913 performance of Stravinsky's "Rite of Spring" and to call it "the most powerfully erotic movie ever made. Bertolucci has altered the facc of an art form". His next production, "1900", made in 1976, was the equally powerful and again controversial study of the dissolution of northern Italy's traditional agricultural society.

In 1975 Bertolucci founded Fiction Films, the company through which he produced his subsequent films, "La Luna” in 1979 and "Tragedy of a Ridiculous Man," in 1981.

The Producer: Jeremy Thomas

JEREMY THOMAS, who was born in Ealing, rather a pithias rare fed some in R, ins it atis include the "Doctor" movies and his uncle, Gerald, directed the highly successful "Carry On" series of films. Cinema has been part of Thomas' life since he was a child and his vacations were spent around the locations or in the studio where his father happened to be working at the time.

Thomas' only ambition was to work in movies and from the age of ten he began to make his own films with friends. Originally, he wanted to be a director but says, "Somehow I ended up being a producer. I would still like to direct but now the reality of what it takes to make a really good film looks more difficult to me.

From school, Thomas went to work in a film processing laboratory and a year later moved into the cutting rooms as an assistant, before graduating to editor, After working with the director Phillipe Mora, editing “Brother, Can You Spare A Dime,” Thomas went with him to Australia in 1974 and there he produced his first film, "Mad Dog Morgan* , which Mora directed He spent two years in Australia and then returned to England where he put together *The Shout" with a screenplay by Michael Austin from a story by Robert Graves, directed by Jerzy Skolimovsky, which won the Grand Prix de lury at the Cannes Film Festival. He then found himself on "the producing circuit", gradually becoming responsible for ambitious projects.

Thomas' films are all extremely individual and owe nothing to box-office patterns of fashionable trends. They range from "The Great Rock’n'Roll Swindle" directed by Julien Temple to “Bad Timing” directed by Nicolas Roeg; “Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence,” directed by Nagisa Oshima; "The Hit" directed by Stephen Frears and "Eureka” and "Insignificance", directed by Nicolas Roeg. Britain's National Film Theatre presented a season of his films and in 1986 he won the prestigious Vittorio de Sicca Prize. In 1987 he was honored by an invitation to be a member of the jury of the Cannes Film Festival.

In 1985 Thomas set up his own film distribution company, Recorded Releasing, which releases some eight films a year. He also founded Recorded Cinemas and through this company owns two cinemas, The Gate in Notting Hill, London, and the Cameo in Edinburgh. He has also set up his own video production company, Vivid.

The Story

Peking, 1908. A three-year old boy is removed from his home and his mother and is carried through the night to the Forbidden City, the heart of ancient China. His name is Pu-Yi.

Days later he is placed on the Dragon Throne and becomes “The Lord of Ten Thousand Years,” ”The Son of Heaven,” ruler over almost half of the world’s population. Py-Yi is the Emperor of China and the loneliest boy on Earth. But three years later, in 1912, China becomes a republic, the Qing dynasty is forced to abdicate, and more than 3,00 years of imperial rule come to an end.

Almost the only person who does not understand this is the boy emperor. While the convulsive tides of modern history transform the world outside, the strange mediaeval life in the Forbidden City hardly changes.

As Pu-Yi grows surrounded by high consorts, courtiers and oven 1500 eunuchs, he is still treated as a god, free to do almost anything he wants, except to live in the present or to set foot outside the palace. Unwittingly, he has been cast as the leading actor in an elaborate play, performed on the largest stage on earth, I which the other actors are conspiring to keep reality for him. Reality if the Chinese people, they are the audience and they have abandoned the theatre long ago.

Pu Yi is 18, married with two wives, when the charade collapses and expels the ex-emperor from the Forbidden City. In 1924 a republican warlord captures Peking and expels the ex-emperor from the Forbidden City. Aided by his friend and tutor, the Scottish Mandarin Sir Reginald Johnson, Pu Yi flees to Tientsin.

For a few years he enjoys the life of a western playboy before becoming increasingly dissatisfied. Now he is an actor without a role, as well as without an audience.

In 1931, Japan invades Manchuria and Pu Yi makes the great choice, and the great mistake of his life. He accepts the Japanese invitation to return to the land of his ancestors and becomes the emperor of the new state of Manchucko. It is the beginning of a nightmare for himself, for China and for the rest of the world which is soon at war.

The last emperor of China is one of the most extraordinary anti-heroes of modern times, an oriental Peter Pan floating like a cork on the stream of history.

His life embraces the whole century, from the end of the Qing dynasty to the first republic of Sun Yat Sen; from the warlords of the twenties to the Kuomintang of Chiang Kai-Shek; from the Japanese invasion to the State of Manchukuo, where Pu Yi becomes a puppet emperor controlled by the Japanese; from the Second World War to the foundation of the People's Republic; from a decade of Mao's re-education programs to the beginning of the Cultural Revolution. In 1959, after ten years in a communist jail, Pu-Yi was pardoned.

In 1960 he returned to Peking and became and gardener in the Botanical Gardens, freer in his terms than he had ever been before. For the first time in his life, he could bicycle in the streets, eat in a restaurant or ride on a public bus.

Traditionally, a Chinese emperor is "the first to sow and the first to reap." His purpose is to set an example. Perhaps Pu-Vi achieved this at the end of his life when he became a citizen of the People's Republic of China. It was the part he played best.

Pu Yi died in 1967.

#Pu-Yi#溥儀#Puyi#Aisin-Gioro Puyi#Yaozhi#曜之#The Last Emperor#David Byrne#Bernardo Bertolucci#Empress Dowager Cixi#Spotify

0 notes

Text

Mutch & Robilliard (B 1981), Puyi Abdicates, 2022

#Google#Images#Art#Contemporary#Digital#Internet#Mutch & Robilliard#Anthony Fineran#Color Theory#Found#Retro#Puyi#Abdicates#China#Newspaper#Black & White

0 notes

Text

🥰💙❤️

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

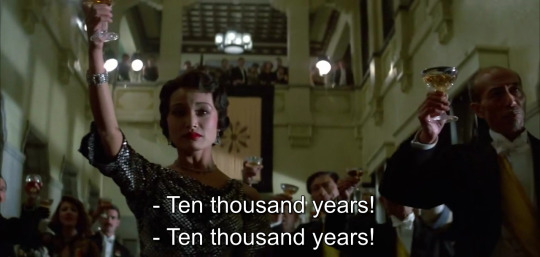

The last emperor, 1987

#biography#drama#history#the last emperor#bernardo bertolucci#enzo ungari#mark peploe#puyi#john lone#joan chen#celebration

46 notes

·

View notes

Note

why the fuck are you reblogging kitschy bourgeois shit from the QING dynasty lmfao. unprincipled leninists not taking the ‘cultural’ part of the cultural revolution seriously again i see. what’s next, shostakovich? ai weiwei?

Sorry for reblogging some cool grape rocks, this is truly a sign of bourgeois decadence that you should spend significant time & effort denouncing to make sure your part of the internet is morally pure. red salute

2K notes

·

View notes

Note

https://vm.tiktok.com/ZGeHBkPve/

puyol saying that gavi is a player he loves, when asked who is the best attacking midfielder in the world ♥️

He sees him as an AM that's very interesting he must've watching in la masía because he's yet to play there in the first team

#PUYI WE LOVE YOU!!!!#he just gets it#pablo gavi#baby waby#carles puyol#fc barcelona#I know he looks at Gavi and sees a lot of himself in him character wise

25 notes

·

View notes