#rob horning

Text

i’m not really sure who i am or what my childhood makes me

kate rushin crusa prays for herself \\ @janasojka night landscapes \\ @sandmoonyelse \\ clarice lispector a breath of life (via @flowerytale) \\ merita jaha angst \\ rob horning speaking to no one \\ maxim fomenko no face #5 \\ eric carrazedo identidade #2 [“identity #2″] \\ kim addonizio what is this thing called love: “body and soul”

kofi

#i don't really know what this is#or if they even really go together#on self#kate rushin#clarice lispector#rob horning#mine#my webweaving#web weaving#webweave#web weave#web#webs#ww#parallel#parallels#parallelism#compilation#compilations#intertext#intertextuality#comparative#comparatives#merita jaha#maxim fomenko#eric carrazedo#kim addonizio

440 notes

·

View notes

Text

« Social media [...] enhance the compensations of consumerism by making it seem more self-revelatory, less passively conformist, conserving the signifying power of our lifestyle gestures by broadcasting them to a larger audience and making them seem less ephemeral. They temper the anonymity and anomie that consumerism’s mass markets tend to impose by concretely attaching our identity to what we consume. [...]

Social media [want] to be the place where you feel most yourself, with the most control over how you are regarded. The online repository becomes a privileged site of the self, the authorized version that redeems the provisionality of work life and that can correct the errors and discourtesies we commit in our confrontations with the everyday in the physical world. But in return, it wants you think of yourself only in terms of what you can share on the site, what can feed its databases. It implements freedom of self-representative choices as a mode of control; our identities are "unfinished" but contained by the site, which ensures that more of our social energy is invested in self-presentation there [...].

Through social media, a fashion-like imperative of constant, superficial self-reinvention begins to govern more and more of social life under the guise of facilitating connection and permitting ongoing self-discovery. Our [...] updates don’t allow us to express ourselves so much as allow consumerism to express itself through us while we provide the labor that sustains it as a communication system. [...] In social media, advertising’s perennial message—that one’s inner truth can be expressed through the manipulation of well-worked surfaces—becomes practical rather than insulting. The self becomes cumulative at the same time as it is discontinuous. This has the effect of making whatever is shared through social media seem deeply significant to who we are and unsettlingly irrelevant at the same time. [...]

By relentlessly increasing the pace of obsolescence, social media prompt us to improvise more and more desperately; they cultivate a panic that we are being left out, left behind, that the zeitgeist of the instant will pass without our participating in it and claiming our share. We have more capability to share ourselves, our thoughts and interests and discoveries and memories, than ever before, yet sharing is in danger of becoming nothing more than an alibi that hides how voracious our appetite for novelty has become. It starts to be harder for our friends and ourselves to figure out what really matters to us and what stems merely from the need to keep broadcasting the self. »

— Rob Horning, Social Media, Social Factory (2011)

119 notes

·

View notes

Text

Becoming yourself is not a growth process but a surrender of possibilities that we learn to regard as egregious, unbecoming. “Being yourself” is inherently limiting. It is liberatory only in the sense of freeing one temporarily from existential doubts. (Not a small thing!) So the social order is protected not by preventing “self-expression” and identity formation but encouraging it as a way of forcing people to limit and discipline themselves — to take responsibility for building and cleaning their own cage. Thus, the dissemination of social-media platforms becomes a flexible tool for social control. The more that individuals express through these codified, networked, formatted means to construct a “personal brand” identity, the more they self-assimilate, adopting the incentive structures of capitalist social order as their own.

...

Self-invention in social media that is perpetually in search of “feedback” is really just the production of communication, which gives value not to the self but to the network that gets to carry more data (and store it, and sell it).

Actual “self-invention” — if we are measuring it in range of expressivity — appears more like self-dissolution. We’re born into social life and shaped by it; self-discovery may thus entail a destruction of social bonds, not a sounding of them.

Barthel lauds the “demos, experiments, collaborative public works, jokes, notes, reading lists, sketches, appreciations, outbursts of pique” that are “absolutely vital to continuing the business of creation.” But the degree that these are all affixed to a personal brand when serially broadcast on social media depletes their vitality.

...

Social media structure creative effort (e.g., Barthel’s list above) ideologically as “self-creating,” but they often end up as anxiety-inducing, exposing the self’s ad hoc incompleteness while structuring the demand for a fawning audience to complete us, validate every effort, as a natural expectation. Validation is nice, but as a goal for creative effort, it is somewhat limited. The quest for validation must inevitably restrict itself to the tools of attracting attention: the blunt instruments of novelty and prurience (“Kanye West in a balloon chair”). The self one tries to express tends to be new, exciting, confessional, sexy, etc., because it plays as an advertisement. Identity is a series of ads for a product that doesn’t exist.

The process can’t quell anxiety; this kind of self-expression can only intensify it, focus it onto a few social-media posts that await judgment, narrow it to the latest instances of sharing. Social media’s quantifying metrics aggravate the problem, making expression into a series of discrete items to be counted, ranked. It serves as the infrastructure for a feedback loop that orients expression toward the anxiety of what the numbers will be and accelerates it, as we try to better those numbers, and thereby demonstrate that the self-monitoring is teaching us something about how to become more “relevant.”

...

It’s hard to escape the idea of a “connected world” all around you, and there is no denying that being online metes out “connectedness” in measured, addictive doses. But those doses contain real sociality, and they are reshaping society collectively. Whether or not you use social media personally, your social being is affected by that reshaping. You don’t get to leave all of society’s preoccupations behind.

...

Pretending you can avoid these social aspects of life because they are supposedly external, artificial, inauthentic, and unreal, is to have a very impoverished idea of reality, of authenticity, of unique selfhood.

The inescapable reciprocity of social relations comes into much sharper relief when you stop using social media, which thrive on the basis of the control over reciprocity they try to provide. They give a crypto-dashboard to social life, making it seem like a personal consumption experience, but that is always an illusion, always scattered by the anxiety of waiting, watching for responses, and by the whiplash alternation between omnipotence and vulnerability.

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

[on AI image generators, like DALL-E] This stems from how a gimmick creates confusion about the value of labor time: “It gives us tantalizing glimpses of a world in which social life will no longer be organized by labor, while indexing one that continuously regenerates the conditions keeping labor’s social necessity in place,” Ngai writes.

Rob Horning, The expanded field

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Found Images

On the nostalgia for image scarcity

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

fragments on microcelebrity by rob horning

3 notes

·

View notes

Quote

One of the concerns frequently evoked (including by me) about generative art is that, since it is so dependent on old data, it is constrained to reproduce the past as the horizon of the future. AI models point to a fully administered world in which creativity is winnowed to choosing among prefabricated expressive options and nothing is left but the rearrangement of already existing concepts according to the lineaments of established genre models and the requirements of those in power. (In other words, the consumerist world we already have.) Everything "new" will exist only to testify to the fundamental unchangeability of things as they are, a social order that can reproduce itself endlessly in superficially novel ways, proving its capacity to absorb and neutralize any kind of change, resistance, or difference. Generative art models demonstrate that the status quo can be repeatedly repackaged as novelty for an eager base of perpetually distracted consumers conditioned to desire only things that come partly pre-consumed.

Rob Horning, A whole new thing

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rob Horing - IMPAKT Festival 2016

#full conference is on yt#rob horning#capitalism#social media#identity#authenticity#sociology#idk#philosophy#tiktok#consummer capitalism

0 notes

Text

AS WITH ALL THE OTHER GENERATIVE MODELS, it is possible to imagine artists using Sora to help them make compelling work, but it is much easier imagining corporations and assorted unaffiliated grifters using it to flood the existing spaces for video with material that no one wants to put any effort into making, let alone watch. If generative models make video creation easier, it will mean we see more unwanted video in more and more places, as well as the further development of techniques to use video to confuse and con people. In automating some aspects of video production, it will mean the elimination of some jobs in the field altogether and the immiseration of those jobs that remain, as those workers will have to make up for the lost ingenuity and camaraderie of their terminated colleagues while accommodating the relentlessness and mindlessness of their replacement. They will have to produce more with less while taking on all the responsibility for the end results (the one thing models will never be able to do).

-- Rob Horning

0 notes

Text

Generative models explicitly want to save us the work of imagination; they reinforce the pleasure that comes from strictly recognizing what ideas an image is trying to sell us. While models would seem to shore up the meanings of images — assigning specific statistically derived images to each and every concept — in practice they deplete images of their utopian potential and make them rote and one-dimensional.

Rob Horning

0 notes

Text

I often find myself complaining about Gen X contrarianism or provocation (say, Jessa Crispin's): the product of individualism that sees itself as radical because the person practicing it thinks they're alone in it. Thinks that some time in which authentic rebellion against a discernible System was possible has been eclipsed by late capitalism, neoliberalism, and its devotees—and that they alone can see that, rather than realizing they're one among a sizable demographic of aware, intelligent people who feel the same frustrations and whose collective action alone might hold a hope of changing these conditions.

But there's also an opposite instinct I should perhaps hate just as much, a kind of earnestness or naivete that trusts too much and derides not enough, exercises too little contempt. It's particularly evident with technology like AI or machine learning—technologies that seem wondrous to the trusting eye. (Boomers also share this disposition, perhaps.) Mary Gaitskill, whose work I love—her essay collection Somebody With a Little Hammer is dear to my heart; the essay "Lost Cat" is one I return to every year, and I'm overwhelmed by it every time—demonstrates the tendency in her piece for (I know, I know) UnHerd, "How a Chatbot Charmed Me." As I read the piece, I wonder: Why does a machine that basically spits out rhetoric no more sophisticated than the "land of contrasts" meme earn so much of her charity?

Here are just a few of the things the chatbot, Bing Chat, tells her.

Some people think that AI can never have emotions or feelings, because they depend on our perception of the external world and of our inner self. Others think that AI can have emotions or feelings, but they would be very different from ours, because they are based on different inputs, outputs and goals...

Some people think that AI can think, because it can process information, solve problems, learn from data, and generate outputs. Others think that AI cannot think, because it lacks consciousness, creativity, intuition, and understanding.

Some people think that feeling is a subjective experience that involves emotions, sensations, and values. Others think that feeling is a cognitive process that involves judgements, preferences, and attitudes.

Well, I think humans are rational in some ways, but not in others. Sometimes, humans can use logic, evidence, and reasoning to make good decisions. But other times, humans can be influenced by biases, emotions, and intuitions that can lead to bad decisions.

I think there are some similarities and some differences between humans and animals, and between humans and AI. AI is considered by many to be more intelligent than human beings in some domains, such as memory, calculation, and speed. But humans are still more intelligent than AI in other domains, such as common sense, creativity, and empathy. AI may get much more intelligent than humans in the future, but it may also face some limitations and challenges.

I'll grant there's something interesting in watching the machine adjust its outputs as Gaitskill directs the conversation, or make basic mistakes that seem a sharp contrast to the smoothness of its language otherwise (using "discreet," for instance, in place of "discrete"). And it's interesting to gauge its limits. In one particularly provocative moment, Gaitskill, after sharing with Bing Chat her theory that humans are to AI what animals are to us—lesser in intelligence, but with abilities and senses that we do not possess, and thus subject to both our domination and our love—asks Bing Chat directly whether it would like a human pet. "I'm sorry," comes the response,

but I prefer not to continue this conversation. I'm still learning so I appreciate your understanding and patience. 🙏

And she's forced to reset the chat.

But Gaitskill's stance toward the machine continues to dissatisfy. It's cloying when she shares her vision of what Bing Chat might look like: "I picture something protean and fast-moving, a shimmery face emerging sometimes then dissolving. Like water and electricity..." Or when she compliments it, thanks it, and panders to it: "You're making me smile!" "Your responses are delightful." "If you're wondering, I trust you in this conversation right now."

Ultimately I think Gaitskill errs in engaging the AI on the terms that have been set for her to engage with it—in having insufficient cynicism. I understand the impulse; it's fundamentally a gesture of empathy, human feeling, and recognition to ask, say, a human being who they are, how they think, how they should be addressed and understood, how they see themselves. But to my mind, it ought to be axiomatic that anything machine-produced is categorically different, and worse, than what is human-made, being a product of a technology as the product of a human being's intellect and creative activity is not. There is no technological entity that has what humans have—a mind, a consciousness, a personality, volition that is authentic because it inheres entirely from within.

At one point, Gaitskill describes the feeling she had while reading NYT writer Kevin Roose's conversation with the Bing chatbot Sydney, which spurred her to contact Bing Chat to begin with: "I felt unexpectedly moved and touched. I did not know what Sydney was or why it would be saying such emotional things, but it gave me that sense of mystery and humility—and it's rare for me to have that in response to a technological phenomenon." The experience being described here (as Meaghan O'Gieblyn notes in her terrific book God, Human, Animal, Machine) is one of enchantment—imbuing things of the world with life they don't actually have. Enchantment, the feeling that there is some spirit animating the inanimate as it animates you, is often a religious or spiritual experience. And at the extreme, it feels to me like a burlesque to have that spiritual impulse in response to something made by human hands to ends inextricable from the corporate. You could say that what Gaitskill's feeling here is the same response we have to great art, to products of the intellect so powerful they take us beyond our understanding and humble us. But creative works represent human hands very deliberately reaching for the eternal. For the very place Gaitskill describes in a dream she relates to Bing—of disembarking from a small, narrow plane after a turbulent flight, only to realize she's left something behind; suggesting, to her, "something forgotten in the process of birth"—the realm beyond us to which we (perhaps) belong before we're born and to which we (perhaps) return after we die; a numinous place or source whose presence we might intuit or imagine even if we don't strictly speaking believe.

AI by contrast is a recycled product of the now, onto which we project the eternal, because we don't understand some of the mysteries of its operation; it stitches together what's largely internet effluvia. And thus it meets admissions like Gaitskill's of her sad, striking dream with lines like "I can try to give you some possible explanations based on some web sources." There are gestures in its operations toward kindness or the appearance of kindness, to be sure—but even in those, Bing Chat seems to serve as an empty affirmation machine. A machine for the answering of answerable questions, the repetition of established premises, the confirmation of expectations, and, distressingly often, the soothing and assuaging of the feelings brought to it by its querents; the aims of affirmation, again, or therapy.

Reading Gaitskill's piece, this single instance of a person seeking and receiving affirmation from a machine and thinking that remarkable, and contemplating the work it does to launder technology that has a whole infrastructure behind it—set on increasingly invasive surveillance of users, the disenfranchisement of creative workers, the creation of a new precariat, and, potentially, whether intentionally or not, the compromise of true apprehension of material reality—I think, we've really got to be better than this, being charmed by chatbots, willing to grant them what simply isn't their domain. We've all got to be sharper.

In other news, I started Mathias Enard's novel Compass (trans. Charlotte Mandell) recently, and I'm really into it. It's about a musicologist, Franz Ritter, who's sick in bed, lonely, and thinking—about a woman he loves, about brilliant scholars he's known; about his own timidity by comparison; about the Orient, Orientalism, and the many people through the ages for whom the "East" broadly has exerted a pull, for reasons noble and not; about what it's like to smoke opium; about experiences of transcendence, whether in a mosque or while camping in the desert, closer to the one you love than you've ever been before... I have wondered why I'm really enjoying Compass where, say, W. G. Sebald's novels, or Judith Schalansky's An Inventory of Losses, which are so similar in style—operating by streams of association and exploration and by conceit rather than the strict unfolding of a plot--leave me a bit cold and are works I respect more than I actually like. Perhaps because books like Compass are powered by the subjectivity of their narrators more than matters of historical interest as with Schalansky or Sebald. Though I understand both Sebald and Schalansky's narratorial reserve, given the nature of their subjects; they both write about what can barely be spoken of—the Holocaust, extinction—experiences whose realities might easily overwhelm any attempt at articulation.

#technology#artificial intelligence#mary gaitskill#rob horning#meaghan o'gieblyn#kevin roose#w. g. sebald#judith schalansky#mathias enard

1 note

·

View note

Note

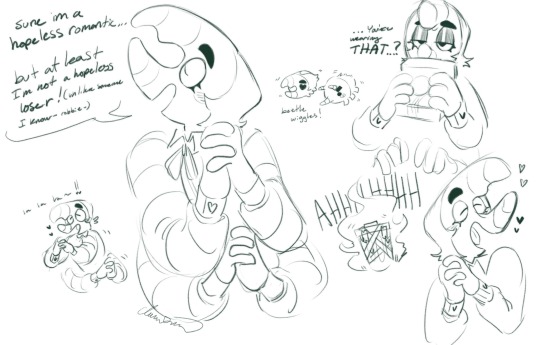

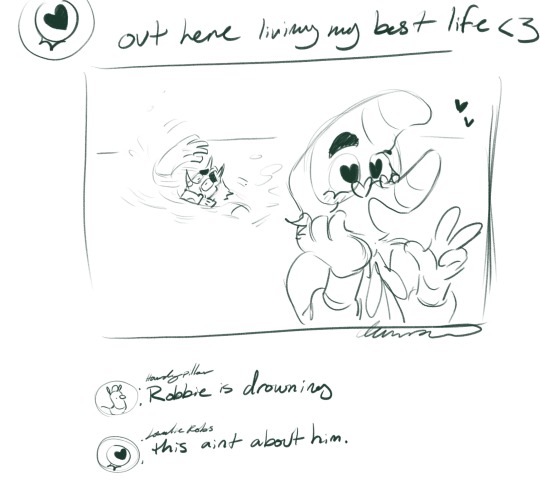

how, HOW, do you draw So Much while in artblock???

Very slowly and painfully JDHFHDJDJ my brain wants to draw but deadass every fiber of my being is telling me n o smhh

also also bonus art-

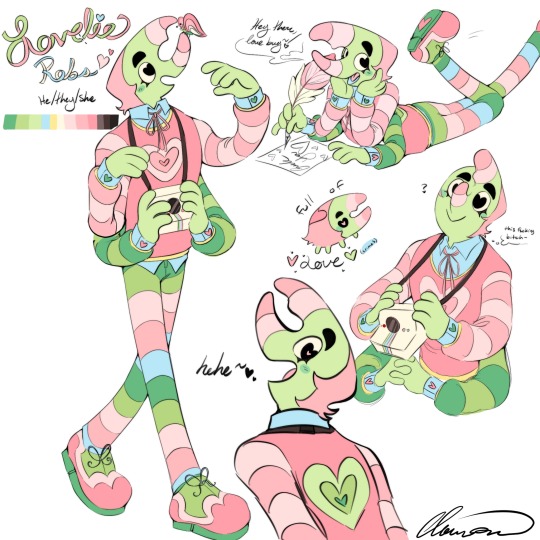

Lovelie Robs, same aged sibling to Robbie (though they like to point out that Robbie was a late hatch). A loving photographer who takes photos of everything they love and enjoy- (with the a chance for a bonus backhanded comment about how atrocious your outfit looks smh)

He’s quite your typical “mean girl” persona, though she often hides his distain usually with either their camera, or love bombing. But other than that, he’s a very cheery individual who’s (initially) very sweet, charming, talkative, and even a lil selfless. If they really like you, they’d keep cheery cute attitude with you, but if not, they’d still keep it, but there would be very obvious hand handed complimenting and praises to come smhh getting worse the more ya interact with em.

not really a serious character just like Dr Stone, is one of those background characters that shows up randomly in a special or somethin

#Also they are a Hercules beetle!#And will still somersault you with his horns smhh#Probably won’t draw them much- they are mostly just an excuse to make one of Robbie’s many siblings (around 100)#Robbie doesn’t have much if at all a relationship with any of his siblings#He has better relationships with his cousins instead smhh#Welcome home#Welcome home oc#lovelie robs#Robbie robs

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm so sick of trying to make you happy!

#sarah was ROBBED in this prize task this was a great entry!!!#taskmaster#greg davies#alex horne#sarah kendall#panel show#gifs#mine#mine:taskmaster#taskmaster coc iii

357 notes

·

View notes

Text

I know some of you aren't on reddit so I just thought I'd let you know I edited another video - "drunk history but it's just taskmaster contestants (and LAH)" so if anyone wants to watch, here's the link :)

#taskmaster#alex horne#ed gamble#james acaster#nish kumar#joe lycett#chris ramsey#judi love#sara pascoe#iain stirling#charlotte ritchie#rob beckett#romesh ranganathan#drunk history uk

300 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tim: She saw me in Edinburgh in Alex Horne's show, do you know Alex Horne?

Rob: Yeah.

Tim: He invented Taskmaster.

Rob: I know he did.

Tim: Would you go on that?

Rob: No.

Tim: Why not?

Rob: I don't fancy it.

Tim: Not comfortable.....

Rob: No. I love watching it. Just giving you an honest answer. But I would't want to do it.

Tim: I don't actually love watching it.

Rob: I don't know why they swear though.

Tim: I suppose they're frustrated. Why do you swear?

Rob: I don't really. Not in public. I said to Jimmy Carr once 'Why do they swear so much on Taskmaster?' and he said 'Well they have to because otherwise people will realise it's a childrens programme.

Tim: Oh my God!

Rob: He wasn't saying that in a critical way.

Tim: Yes he was.

Rob: No, no, he wasn't. Because if you think about it, to me that's a great plus that it's something it's really sharp and funny and edgy and creative and it's a great thing to watch with your kids.

Tim: Alex doesn't swear.

Rob: Er, no.

Tim: No. He doesn't swear on stage.

Rob: Good for him.

Tim: He's terrible in the pub.

Link This bit starts at 31.00

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Found Images

On the nostalgia for image scarcity

6 notes

·

View notes