#sacque back

Text

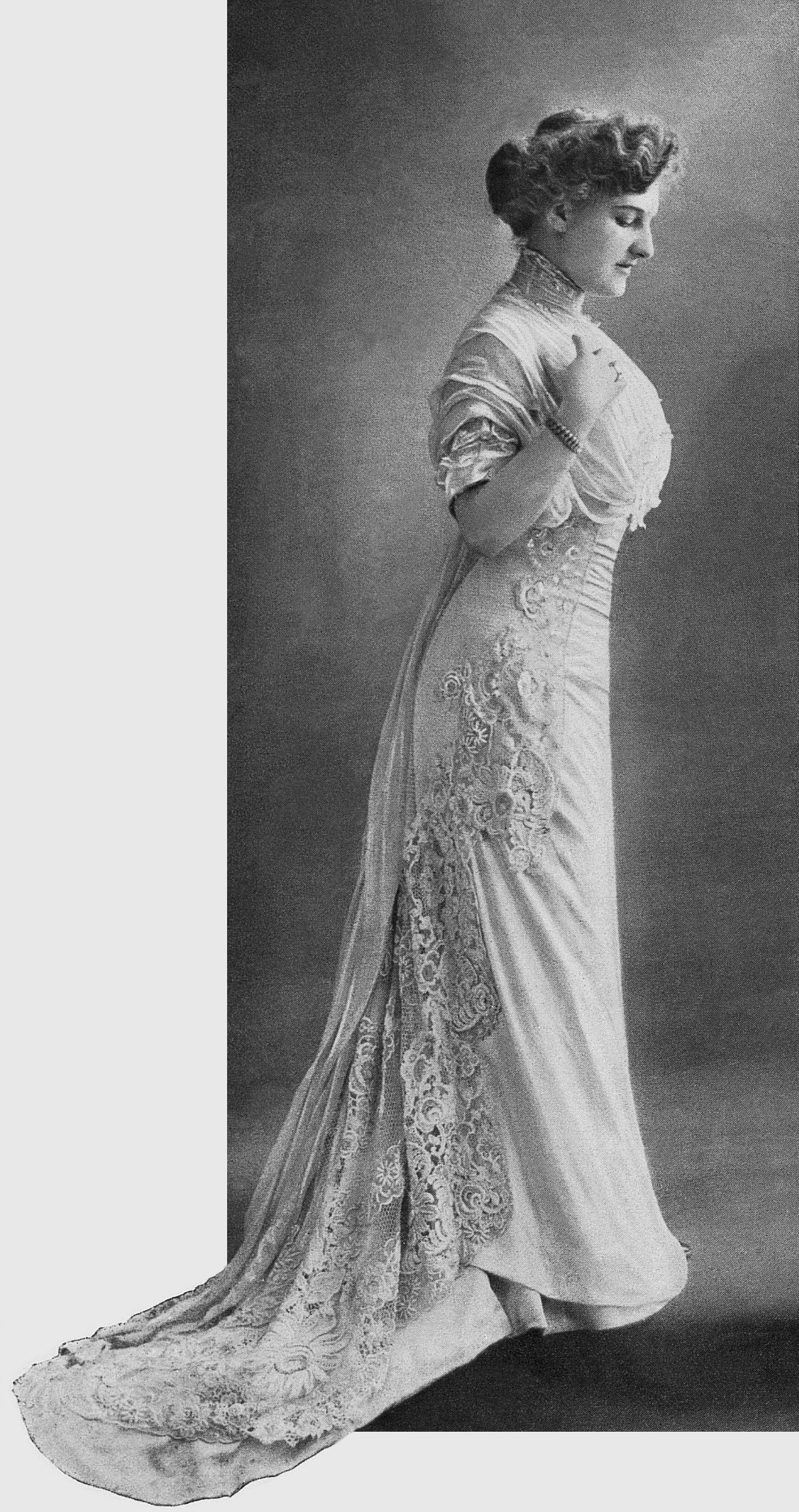

1908 (June issue) Les Modes - Robe de diner par Beer - photo by Reutlinger. From gallica.bnf.fr; fixed flaws & spots w Pshop 1028X1958.

#1908 fashion#1900s fashion#Belle Époque fashion#Edwardian fashion#Beer#Reutlinger#dinner dress#clerical neckline#fichu#elbow-length sleeves#sacque back#close skirt#lprincess cut#parasol

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’m slogging through hand sewing the trim for my sacque gown, so enjoy these detail shots. Trying to motivate myself, but whip gathering 300” of trim is kind of boring 😅

#historical fashion#18th century#rococo#1770s#1780s#18th century fashion#sewing project#sewing#hand sewing#historical costuming#modiste#robe a la francaise#sacque gown#sacque back gown

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Title: Robe à la Française

Date: 1730–40

Culture: European

Medium: silk, metal

The MET Museum

This is an extraordinary example of weaving incorporating silver metallic threads in a very distinctive design. This textile was identified as an identical match to the textile of a gown worn to a Russian Imperial wedding in the in the 1730s.

Women with coquettish airs were imposing in robes à la française and robes à l'anglaise throughout the period between 1720 and 1780. The robe à la française was derived from the loose negligee sacque dress of the earlier part of the century, which was pleated from the shoulders at the front at the back. The silhouette, composed of a funnel-shaped bust feeding into wide rectangular skirts, was inspired by Spanish designs of the previous century and allowed for expansive amounts of textiles with delicate Rococo curvilinear decoration. The wide skirts, which were often open at the front to expose a highly decorated underskirt, were supported by panniers created from padding and hoops of different materials such as cane, baleen or metal. The robes à la française are renowned for the beauty of their textiles, the cut of the back employing box pleats and skirt decorations, known as robings, which showed endless imagination and variety.

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

Robe à la française

Also known as a sack-back gown. It was a women’s fashion of 18th century Europe. At the beginning of the century, the sack-back gown was a very informal style of dress. At its most informal, it was unfitted both front and back and called a sacque, contouche, or robe battante. By the 1770s the sack-back gown was second only to the court dress in its formality. This style of gown had fabric at the back arranged in box pleats which fell loose from the shoulder to the floor with a slight train. In front, the gown was open, showing off a decorative stomacher and petticoat. It would have been worn with a wide square hoop or panniers under the petticoat. Scalloped ruffles often trimmed elbow-length sleeves, which were worn with separate frills called engageantes. The casaquin (popularity known from the 1740s onwards as a pet-en-l’air) was an abbreviated version of the robe à la française worn as a jacket for informal wear with a matching or contrasting petticoat. The loose box pleats which are a feature of the sack-back gown style are sometimes called Watteau pleats from their appearance in the paintings of Antoine Watteau.

277 notes

·

View notes

Text

Victorian Fashion Rules: Riding in a Carriage

For driving in a handsome private carriage through the streets of a large city, or in the fashionable Park, the most elaborate out- door costume is expected. Richest silk, velvet, and lace, are all appropriate, and elaborate style and trimming are allowable. In summer, light, thin goods, shawls of white or black lace, dainty lace bonnets, gloves of light-colored kid, light, dressy boots, collars and cuffs of fine lace, and jewelry that is rich and tasteful, are all strictly appropriate for the full dress drive, while in cooler weath- er, the white velvet sacque, black velvet cloak, or rich wrap of any material may be worn. – The Art of Dressing Well

Ludwig Passini (Austrian, active in Italy, 1832-1903) • The Carriage Ride • Unknown date

Jean Béraud (French, 1849-1935) • Nous Rentrons! (We're Going Back!) • Late 19th century

Sources:

Frost, S. Annie (1870) . Outdoor Dresses - Riding . The Art of Dressing Well. A Complete Guide to Economy, Style and Propriety of Costume (p. 52) . Dick & Fitzgerald . https://www.loc.gov/resource/gdcmassbookdig.artofdressingwel00fros/?sp=9&st=image&r=-0.246,-0.037,1.397,1.627,0

Pinterest

Wikipedia

#fashion history#art history#victorian fashion#victorian fashion rules#jean béraud#19th century paris paintings#ludwig passini#art#painting#genre painting#the art of dressing well#art & fashion#art & fashion history blog#the resplendent outfit

17 notes

·

View notes

Note

List 5 facts about a favorite sim of yours, and send this to simblrs whose sims you adore 💜

I'm sorry this is so late! I got terribly distracted.

I'm going to talk about Lady Venetia Beaumaris Gracefield, as she will be taking quite a prominent role in the Bachelor Challenge! (She's the lady in black, of course.)

Lady Venetia's actual name--as written in the baptismal records--is Mary Anne Venetia Beaumaris, as the parish priest disapproved of the name "Venetia" due to associations with Venetia Stanley, the scandalous society woman. When Mr. Beaumaris insisted upon the name, he added an extra saint's name for good measure. Of course, the family ignored the correction, and she was only known by "Venetia" except for official documents, religious purposes, and letters from the more prim and proper great-aunts. Venetia, upon her marriage, quietly dropped the "Mary Anne" out of her signature, and never looked back.

She has five living children, ranging in age from fifteen to seven. Their names are Frederick, Beatrix, Humphrey, Noel, and Sophia. Frederick and Humphrey attend a posh boarding school in London. Noel is already serving in the Navy, and the girls are educated at home. She is not a terribly affectionate mother, but cares for them anyways, like she cares for her rose-garden; she will be happy when they are all grown up, married, and out of the house so she can have adult conversations with them. (Noel will be perfectly fine, for anyone who's seen "Master and Commander" and gotten anxious reading that; he will die at the age of seventy-four, in his sleep, on land, surrounded by friends and family, though of course Venetia doesn't know this, and neither should any of us...)

Venetia is not a merry widow, despite her fondness for fun and games and salacious gossip; she was deeply hurt by her husband's death some years ago. It was very sudden, and the precarity she and her children experienced until the (highly contested) will was settled and her 'regency' for her eldest son was in place was not something she enjoyed. Not to mention, you know, her husband died, and she quite liked her husband! She won't marry again, mostly because she is done with having children and wants to be absolutely certain she won't get a late-in-life surprise!

She is a prolific letter-writer, and keeps everyone she knows well up-to-date on every piece of gossip and every event she knows of. This ranges from "who spilled tea on their new silk sacque" to details of the militia training that would make the commander blow a gasket if it were to fall into enemy hands to a fevered account of the illness of Mrs. Y's prize pig. (All in the same paragraph, if not in the same sentence.) Venetia also keeps a secret log of every letter she's sent, plus a description of the contents, because she frequently gets replies stating, in essence, "Venetia, WHAT are you talking about, I don't remember anything about Mrs. W's ugly child..."

Venetia secretly--and guiltily--hopes that either Humphrey or Noel will inherit Ferncombe Hall when Gregory dies. After all, there's no guarantee that one will have children, let alone have children who meet the requirements for the entail. (Not that she has such a problem, with three healthy boys.) She knows she's not supposed to think such things, and it would be awful if she borrowed trouble for her brother and his family. But it would make her boys' prospects a bit sunnier, with Humphrey not having a parish living to give him a house and Noel having to be very careful with his prize-money if he remains in the Navy, if there was a house and income for one of them. Her idea of making up for this is to get Gregory settled, and then hope that he produces a litter of children as quickly as possible, so that her boys' chance of inheritance keeps being bumped down the ladder.

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

i know this question is very general, but is there a list of the types of mantuas/robes there is out there? i thought there was only robe a la francaise, but it turns out that there are robe a l’anglaise and robe volante? are there more?

Thank you for the question! I'm actually working on a post about this specific subject! Or it will be more broadly about all the types of dress from 18th century. I want to do an in depth look and there's still some research to be done. It might not be my next post so I'll give a quick overview of mantua anyway here.

Mantua and It's Variants

So there indeed is more than robe a la francaise, robe a l'angaise and robe volante! Mantua was developed from banyan, which was a dressing gown used by both men and women and inspired by Japanese kimono. It was brought to Europe by the Dutch East Indian Company in mid 17th century. It was a very casual clothing, used only in home. In 1680s it was developed into a little more formal dress, appropriate to use outside in casual situations. The formal dress had a highly boned bodice and was used without stays. It was rigid and uncomfortable, and so naturally there was a need for a more comfortable casual dress that's not only reserved for home.

Here's an early mantua from 1680s worn with stays exposed in the front and contrasting fine petticoat. It became an instant hit. It was used with stays to still get the fashionable silhouette, but the mantua itself was very loose. It was draped to fit the bodice and fastened with belt. It was more comfortable and less restrictive and it could be easily adjusted for body changes, pregnancy and other people. It very quickly became the popular mode of clothing and in 18th century was developed into a lot of different dresses, though the old type of boned dress was still used as the court gown.

Robe Volante

Robe Volante was a transitional dress from mantua to robe a la francaise in the early 18th century. The example is from 1731. It was basically mantua, except box pleats in the back and not belted to be fitted. It was only used in comfort of home, but young fashionable women started wearing it in casual park outings which at first cause a stir. After that it quickly developed into the robe a la francaise we all know and love today.

Robe a la francaise

Robe a la francaise is the most iconic Rococo mantua. It was also called sack-back gown or sacque because of the loose box pleats in the back. As said earlier it started as very informal dress. Like in this example from 1731 it's used in casual outing in a park. It's very loose in the back and front. This maybe could still be called robe volante as it's very much in the transitional phase and these terms are loose and we'll see how hard they are to pin down.

Later in the century it became very formal, the only more formal dress was the court gown. You might start to see a pattern here. It reached it's peak in elaboration and formality in 1770s like in this example from 1775. The formal gowns became extremely wide by 1770s. The pleats started to be sewn closed and not just pinned.

Pet en l'air

Pet en l'air was a short version of robe a la francaise. It came in to use fairly early in 18th century as robe a la francaise home version. It wasn't appropriate to wear it outside, but it was formal enough to receive quests in it. It started as about knee length but got shorter towards the end of the century. This example is from 1770s. And like everything else it became more formal, women also started to use it outside in as an informal wear in 1770s and 1780s.

Robe a l'angaise

Robe a l'angaise was popularized in the latter half of the 18th century. It was English origin as the name suggests. The English had a more subdued fashion than the French and it shows in the robe a l'anglaise. It was also more casual than the robe a la francaise which at that point had become formal. It was also called closed-bodied gown because the bodice was closed at the front, unlike sacque, and the pleased were in the back too stitched to be fitted to the body. In 1780s the bodice started to be sewn out separately and the pleats were gone. It also became formal as robe a la francaise went out of fashion because of the political tensions encouraged a less elaborate form of dress.

Round gown

Round gown was otherwise the same as robe a l'anglaise except it was not robe at all and the skirt was too fully closed. It was very casual dress earlier in the century and in 1780s became very popular and eventually turning into the Regency dress. Term round gown is sometimes used interchangeably with robe a l'anglaise.

Robe a la polonaise

Robe a la polonaise, or polonaise, was used in 1770s and 1780s. The example is from 1777. It developed in France from robe a l'anglaise as that was popularized in France. The name comes from Polish as apparently some part of it was inspired by Polish national dress, but that could be just what the French said at the time to make it more "exotic". It has the sewn down pleats of robe a l'anglaise, but it was sometimes open in front and only pinned at the top. There were though a examples with closed bodice in the front. What made it polonaise though was the skirt part was draped up at the back, making it sack. This practice was started by middle class women, who wanted to prevent the skirt from getting dirtied as walking outside and it became fashionable. As the use of outside walking suggests, it was formal enough to use outside but quite informal and not for any fancy occasions.

Robe a la turque

We are starting to reach some of the most confusing dresses of the time, which mostly happened around 1780s. Robe a la turque was supposedly inspired by Turkish fashion. It was fashionable in 1770s to 1790s and developed from polonaise. The example is from late 1780s. What is usually considered robe a la turque is the robe with bodice open at the front except joined at the very to, and the skirt of the robe not being draped up like in polonaise. As polonaise would often have the same type of bodice. But it gets weird since the example I'm using here is sometimes labeled robe a l'anglaise and there is other weirdness around what was called polonaise and levite (which we'll get to) etc. Here's a blog post that talks about well how confusing this time period is.

Robe Levite

Robe Levite or robe a la Levite or only Levite was popular around the same time as polonaise and turque. The example is from early 1780s. It was again an new type of more casual dress. The back is sewn fitted like in other robe a l'anglaise variants, but it's open and more robe-like. In some examples I've seen the front of the bodice is pinned together though. The maybe most defining characteristics is the sash on the waist.

I think I remembered everything, or I hope I did because I reached the image limit. There's of course more types of dress, like the court gown, chemise a la reine and the bed gown, which were not mantua variants. And I have to reiterate, these term are often very vague and used interchangeably. Fashion was changing so rabidly at the time there were many contemporary terms used in chaotic ways, and it has become even more muddled as later terms have been applied to earlier modes of dress. These are my interpretations of the terms and I'm not going to claim they are the right ones, but other people have used the terms similarly so I'm not just pulling it out of my ass either.

#answers#fashion#history#fashion history#historical fashion#dress history#rococo#18th century fashion#rococo fashion#historical clothing#mantua#robe a la francaise#robe a l'anglaise

183 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fashion history repeats itself. Sack gown to Watteau pleats to modern deconstruction of the sack gown.

Image 1: 1760s-1770s sack gown. Back view showing the two double box pleats. Also called a sack-back gown, sacque, or robe à la française. This would have been worn over a pair of stays, and hoops or panniers to support the skirt.

Image 2: 1890s tea gown. Back view showing Watteau pleats. Unlike the 18th century sack, tea gowns were informal, at-home wear. The bodice of tea gowns was often boned and the linings were fitted, even though the outside looks loose and flowy. Theoretically tea gowns could be worn without a corset. But, people were wearing these to receive friends at their home for tea, and not wearing a corset would likely feel similar to going bra-less today. I personally would feel a little too exposed having friends over with no bra, even if I'm otherwise in comfy, informal clothes.

Image 3: The Two Cousins, 1716 painting by Antoine Watteau. Pleated or gathered backs were called Watteau pleats starting in the 19th century, taking inspiration from the sack gowns depicted in Watteau's paintings. No one in Watteau's time or the rest of the 18th century would have called them Watteau pleats or Watteau gowns.

Image 4: Watteau, 1996 Vivienne Westwood evening gown, inspired by 18th century sack gowns, but with modern elements like the asymmetry of the trimmings and side-hoop pouf. The description from the V&A says this gown has double box pleats in the back, like the 18th-century sack gowns, but weirdly, does not seem to have a view of this gown from the back.

#fashion history#v&a museum#victorian fashion#tea gown#19th century#18th century#19th century fashion#sack gown#watteau

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

One thing that I really love about the costuming in Our Flag Means Death is the way that Mary Bonnet's look changes so significantly through her arc.

In Discomfort in a Married State, married and pre-married Mary wears reasonably historical clothes. The wedding dress is a quite good 1750s-1760s design (I think it's a sacque, ie a robe à la française) with perfect self-fabric sinuous trim, and I do mean perfect. The brown satin mantua has the shorter sleeves with cuffs of the late 1710s-1720s and is worn with a fashionably unmatching stomacher that looks kinda like a 1710s-1720s bizarre silk brocade. The gown she wears when being painted with Stede is a style from the ~1660s, a little awkwardly fitting because the neckline's a bit too high, but the shape, the placement of the sleeves, the style of the trim are all quite right. Other costumes like the yellow gown or the one she wears when berating Stede as a hallucination are also pretty accurate to the late 18th century, particularly the hallucination costume. Her bangs are modern but the long sausage curls with one hanging over the shoulder are really common in early 18th century portraiture. (Please forgive my potato-quality screencaps.)

Self-actualized, happy Mary, on the other hand, is not dressed in reproduction-style costumes. She generally wears a white blouse with a black skirt, something not even really possible in the 18th century - this is a kind of outfit that picked up as informal morning dress in the 1850s and can be found from them on. (The short-sleeved blouse is fully modern; the long-sleeved one is ambiguously 19th-20th-21st century.) That checked jacket is also not from a time period, either: the big turn-back cuffs are reminiscent of 18th century gowns and coats, but the overall look - flaring sleeves, lapels, open over a white shirt but buttoned at the waist - reminds me a ton of riding habits from the 1840s-1850s. Her hair is entirely up in a modern kind of bun.

This is way more in line with the "give no shits" vibe of the costuming for the pirates - modernity where you want, historical references in other places, overall it's a Look that isn't beholden to anyone. And it's not like this is what all the widows wear - actually, the rest of them wear pretty reasonable 18th century gowns, even Evelyn. Which I think says something about Mary being the one who's truly living her best life.

#ofmd#ofmd costuming#our flag means death#mary bonnet#god it's impossible to find screencaps of Mary

69 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Just Do the Math: Knitting In Another Gauge

It is an odd thing but many people seem to veer away in terror from not very hard math. I once asked an excellent knitter (wearing a lace shawl with leaf motifs!) about reworking a knitting pattern because I could not hit gauge with the yarn I wanted to use, and she shied like a frightened horse and said, she has a knitting friend who could do that but she would NEVER try. In her book on writing patterns for knitting, Kate Atherley quotes a woman who seems irate that any pattern would tell her to make 12 decreases evenly distributed along a row, instead of telling her how many stitches between the decreases.

Notice we are talking about needing to do multiplication and division which are the kind of math we learned in grade school. The kind of math we started out learning with flash cards. Which makes me want to say, have a little respect for your brain: Just Do the Math.

So here is my doing the math on a baby sacque from the Good Housekeeping NEW Complete Book of Needlecraft, reprint of a 1959 edition with some added patterns in 1971. The original used “Baby wool” at 7 knit stitches to the inch and I had baby yarn given to me by a friend and could only get 5 stitches per inch even with small needles. I looked over the pattern, realized they had given the measurements which amount to a schematic in words and sketched it out. Then I went through the pattern and recalculated all the number of stitches given in the new gauge. So casting on of 60 stitches turned into 43, knitting 46 stitches until turning back with the white yarn became 33 stitches, then the 26 stitches slipped onto a holder for the side seam became 19, the sleeve itself meant casting on 30 stitches which became 21. You can always use a calculator for this kind figuring.

Vintage patterns from the 1950s usually offered no schematics, and no charts, and sometimes told knitters to just do the math. Some knitting books urged readers to feel free to choose a different stitch pattern and then do the math to make it work. I suspect the simplification of most patterns after the 1960s meant that younger knitters no longer got into the practice of doing the math. I also suspect that the idea of altering a knitting pattern seems more natural to me since I have been altering the schematics we call sewing patterns for many years.

I say we honor our knitting forbears and just do the math. There is little to lose and a whole world of design flexibility to gain.

#knitting#knitting patterns#vintage knitting patterns#writing knitting patterns#knitting gauge#just do the math#good housekeeping new complete book of needlecraft#vintage knitting#vintage knitting book#1950s fashions#history of knitting#garment design#kate atherley#baby sacque

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Back to the 1770s -

Top left 1770-1775 Front of robe à la Française (Metropolitan). From tumblr.com/antiquelaceartist 2048X2743.

Top right 1770-1775 Back of robe à la Française (Metropolitan). From tumblr.com/antiquelaceartist 2048X2883.

Second row 1776 Friederike Elisabeth and Wilhelmine Oeser by Johann Tischbein the Elder (Goethe Haus - either Frankfurt am Mein or Weimar, Germany). From tumblr.com/la-reinette 960X760.

Third row 1778 Countess of Fries Portrait by Alexander Roslin (location ?). From Merinok's Facebook pages 1440X1800.

#1770s fashion#Louis XV hashion#Louis XVI fashion#Georgian fashion#rococo fashion#robe à la française#sacque back#Friederike Elisabeth and Wilhelmine Oeser#Johann Tischbein the Elder#straight hair#square décolletage#floral headdress#Countess of Fries#Alexander Roslin.feathered cap#fur-trimmed robings#fur trim#three-quarter length sleeves#lace engageantes#gloves#fan

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

#small youtuber#sewing youtuber#sewing project#robe a la francaise#sacque gown#sacque back gown#historical costuming youtuber#historical costuming#historical hand sewing#historical fashion#hand sewing project#creator#18th century#18th century fashion#modiste#handmade garment#Youtube

0 notes

Text

American Girl Truly Me #44 modeling historical dresses sewn by Laura of LoveFromLola:

1770s pink dress (Felicity Christmas Gown by Pleasant Company)

1770s green dress (Sacque Back gown by Thimbles and Acorns)

1770s red dress (Sacque Back gown by Thimbles and Acorns)

1780s dress (Elizabeth by Pemberly Threads)

1790s yellow dress (1790 Redingote pattern by Pemberly Threads)

1790s tan dress (1790 Redingote pattern by Pemberly Threads)

Late 1700s/Early 1800s yellow Regency dress (patterns by Pemberley Threads)

1800s dress and apron

1830s blue dress (patterns by Pemberley Threads)

1830s red dress (pattern by Pemberley Threads)

Green 1840s dress (Jane Eyre by Pemberly Threads)

1840s yellow dress (Jane Eyre by Pemberly Threads)

1840s tan dress (Jane Eyre by Pemberly Threads)

1840s blue dress (Jane Eyre by Pemberly Threads)

1840s copper dress (Jane Eyre by Pemberly Threads)

1840s red dress (Jane Eyre and Chemisette & Capelet patterns by Pemberly Threads)

1840s burnt orange dress (Jane Eyre and Chemisette & Capelet patterns by Pemberly Threads)

1840s green floral dress (Molly by Pemberly Threads)

1840s red dress (Molly by Pemberly Threads)

1840s olive dress (Molly by Pemberly Threads)

1860s yellow dress

1860s dress (Meg by Pemberly Threads)

1870s yellow bustle dress (Literary Society and Lobster tail Bustle patterns by Thimbles and Acorns)

1870s pink bustle dress (Literary Society and Lobster tail Bustle patterns by Thimbles and Acorns)

0 notes

Text

Little Women, Louisa May Alcott

Chapters 9-10

IX.

MEG GOES TO VANITY FAIR.

"I do think it was the most fortunate thing in the world that those children should have the measles just now," said Meg, one April day, as she stood packing the "go abroady" trunk in her room, surrounded by her sisters.

"And so nice of Annie Moffat not to forget her promise. A whole fortnight of fun will be regularly splendid," replied Jo, looking like a windmill, as she folded skirts with her long arms.

105 "And such lovely weather; I'm so glad of that," added Beth, tidily sorting neck and hair ribbons in her best box, lent for the great occasion.

"I wish I was going to have a fine time, and wear all these nice things," said Amy, with her mouth full of pins, as she artistically replenished her sister's cushion.

"I wish you were all going; but, as you can't, I shall keep my adventures to tell you when I come back. I'm sure it's the least I can do, when you have been so kind, lending me things, and helping me get ready," said Meg, glancing round the room at the very simple outfit, which seemed nearly perfect in their eyes.

"What did mother give you out of the treasure-box?" asked Amy, who had not been present at the opening of a certain cedar chest, in which Mrs. March kept a few relics of past splendor, as gifts for her girls when the proper time came.

"A pair of silk stockings, that pretty carved fan, and a lovely blue sash. I wanted the violet silk; but there isn't time to make it over, so I must be contented with my old tarlatan."

"It will look nicely over my new muslin skirt, and the sash will set it off beautifully. I wish I hadn't smashed my coral bracelet, for you might have had it," said Jo, who loved to give and lend, but whose possessions were usually too dilapidated to be of much use.

"There is a lovely old-fashioned pearl set in the treasure-box; but mother said real flowers were the prettiest ornament for a young girl, and Laurie promised to send me all I want," replied Meg. "Now, let me see; there's my new gray walking-suit—just curl up the feather in my hat, Beth,—then my poplin, for Sunday, and the small party,—it looks heavy for spring, doesn't it? The violet silk would be so nice; oh, dear!"

"Never mind; you've got the tarlatan for the big party, and you always look like an angel in white," said Amy, brooding over the little store of finery in which her soul delighted.

"It isn't low-necked, and it doesn't sweep enough, but it will have to do. My blue house-dress looks so well, turned and freshly trimmed, that I feel as if I'd got a new one. My silk sacque isn't a bit the fashion, and my bonnet doesn't look like Sallie's; I didn't 106 like to say anything, but I was sadly disappointed in my umbrella. I told mother black, with a white handle, but she forgot, and bought a green one, with a yellowish handle. It's strong and neat, so I ought not to complain, but I know I shall feel ashamed of it beside Annie's silk one with a gold top," sighed Meg, surveying the little umbrella with great disfavor.

"Change it," advised Jo.

"I won't be so silly, or hurt Marmee's feelings, when she took so much pains to get my things. It's a nonsensical notion of mine, and I'm not going to give up to it. My silk stockings and two pairs of new gloves are my comfort. You are a dear, to lend me yours, Jo. I feel so rich, and sort of elegant, with two new pairs, and the old ones cleaned up for common;" and Meg took a refreshing peep at her glove-box.

"Annie Moffat has blue and pink bows on her night-caps; would you put some on mine?" she asked, as Beth brought up a pile of snowy muslins, fresh from Hannah's hands.

"No, I wouldn't; for the smart caps won't match the plain gowns, without any trimming on them. Poor folks shouldn't rig," said Jo decidedly.

"I wonder if I shall ever be happy enough to have real lace on my clothes, and bows on my caps?" said Meg impatiently.

"You said the other day that you'd be perfectly happy if you could only go to Annie Moffat's," observed Beth, in her quiet way.

"So I did! Well, I am happy, and I won't fret; but it does seem as if the more one gets the more one wants, doesn't it? There, now, the trays are ready, and everything in but my ball-dress, which I shall leave for mother to pack," said Meg, cheering up, as she glanced from the half-filled trunk to the many-times pressed and mended white tarlatan, which she called her "ball-dress," with an important air.

The next day was fine, and Meg departed, in style, for a fortnight of novelty and pleasure. Mrs. March had consented to the visit rather reluctantly, fearing that Margaret would come back more discontented than she went. But she had begged so hard, and Sallie had promised to take good care of her, and a little pleasure seemed 107 so delightful after a winter of irksome work, that the mother yielded, and the daughter went to take her first taste of fashionable life.

The Moffats were very fashionable, and simple Meg was rather daunted, at first, by the splendor of the house and the elegance of its occupants. But they were kindly people, in spite of the frivolous life they led, and soon put their guest at her ease. Perhaps Meg felt, without understanding why, that they were not particularly cultivated or intelligent people, and that all their gilding could not quite conceal the ordinary material of which they were made. It certainly was agreeable to fare sumptuously, drive in a fine carriage, wear her best frock every day, and do nothing but enjoy herself. It suited her exactly; and soon she began to imitate the manners and conversation of those about her; to put on little airs and graces, use French phrases, crimp her hair, take in her dresses, and talk about the fashions as well as she could. The more she saw of Annie Moffat's pretty things, the more she envied her, and sighed to be rich. Home now looked bare and dismal as she thought of it, work grew harder than ever, and she felt that she was a very destitute and much-injured girl, in spite of the new gloves and silk stockings.

She had not much time for repining, however, for the three young girls were busily employed in "having a good time." They shopped, walked, rode, and called all day; went to theatres and operas, or frolicked at home in the evening; for Annie had many friends, and knew how to entertain them. Her older sisters were very fine young ladies, and one was engaged, which was extremely interesting and romantic, Meg thought. Mr. Moffat was a fat, jolly old gentleman, who knew her father; and Mrs. Moffat, a fat, jolly old lady, who took as great a fancy to Meg as her daughter had done. Every one petted her; and "Daisy," as they called her, was in a fair way to have her head turned.

When the evening for the "small party" came, she found that the poplin wouldn't do at all, for the other girls were putting on thin dresses, and making themselves very fine indeed; so out came the tarlatan, looking older, limper, and shabbier than ever beside Sallie's crisp new one. Meg saw the girls glance at it and then at one another, and her cheeks began to burn, for, with all her gentleness, she 108 was very proud. No one said a word about it, but Sallie offered to dress her hair, and Annie to tie her sash, and Belle, the engaged sister, praised her white arms; but in their kindness Meg saw only pity for her poverty, and her heart felt very heavy as she stood by herself, while the others laughed, chattered, and flew about like gauzy butterflies. The hard, bitter feeling was getting pretty bad, when the maid brought in a box of flowers. Before she could speak, Annie had the cover off, and all were exclaiming at the lovely roses, heath, and fern within.

"It's for Belle, of course; George always sends her some, but these are altogether ravishing," cried Annie, with a great sniff.

"They are for Miss March, the man said. And here's a note," put in the maid, holding it to Meg.

"What fun! Who are they from? Didn't know you had a lover," cried the girls, fluttering about Meg in a high state of curiosity and surprise.

"The note is from mother, and the flowers from Laurie," said Meg simply, yet much gratified that he had not forgotten her.

"Oh, indeed!" said Annie, with a funny look, as Meg slipped the note into her pocket, as a sort of talisman against envy, vanity, and false pride; for the few loving words had done her good, and the flowers cheered her up by their beauty.

Feeling almost happy again, she laid by a few ferns and roses for herself, and quickly made up the rest in dainty bouquets for the breasts, hair, or skirts of her friends, offering them so prettily that Clara, the elder sister, told her she was "the sweetest little thing she ever saw;" and they looked quite charmed with her small attention. Somehow the kind act finished her despondency; and when all the rest went to show themselves to Mrs. Moffat, she saw a happy, bright-eyed face in the mirror, as she laid her ferns against her rippling hair, and fastened the roses in the dress that didn't strike her as so very shabby now.

She enjoyed herself very much that evening, for she danced to her heart's content; every one was very kind, and she had three compliments. Annie made her sing, and some one said she had a remarkably fine voice; Major Lincoln asked who "the fresh little girl, with 109 the beautiful eyes," was; and Mr. Moffat insisted on dancing with her, because she "didn't dawdle, but had some spring in her," as he gracefully expressed it. So, altogether, she had a very nice time, till she overheard a bit of a conversation, which disturbed her extremely. She was sitting just inside the conservatory, waiting for her partner to bring her an ice, when she heard a voice ask, on the other side of the flowery wall,—

"How old is he?"

"Sixteen or seventeen, I should say," replied another voice.

"It would be a grand thing for one of those girls, wouldn't it? Sallie says they are very intimate now, and the old man quite dotes on them."

"Mrs M. has made her plans, I dare say, and will play her cards well, early as it is. The girl evidently doesn't think of it yet," said Mrs. Moffat.

"She told that fib about her mamma, as if she did know, and colored up when the flowers came, quite prettily. Poor thing! she'd be so nice if she was only got up in style. Do you think she'd be offended if we offered to lend her a dress for Thursday?" asked another voice.

"She's proud, but I don't believe she'd mind, for that dowdy tarlatan is all she has got. She may tear it to-night, and that will be a good excuse for offering a decent one."

"We'll see. I shall ask young Laurence, as a compliment to her, and we'll have fun about it afterward."

Here Meg's partner appeared, to find her looking much flushed and rather agitated. She was proud, and her pride was useful just then, for it helped her hide her mortification, anger, and disgust at what she had just heard; for, innocent and unsuspicious as she was, she could not help understanding the gossip of her friends. She tried to forget it, but could not, and kept repeating to herself, "Mrs. M. has made her plans," "that fib about her mamma," and "dowdy tarlatan," till she was ready to cry, and rush home to tell her troubles and ask for advice. As that was impossible, she did her best to seem gay; and, being rather excited, she succeeded so well that no one dreamed what an effort she was making. She was very glad when it was all over, and she was quiet in her bed, where she could think and wonder 110 and fume till her head ached and her hot cheeks were cooled by a few natural tears. Those foolish, yet well-meant words, had opened a new world to Meg, and much disturbed the peace of the old one, in which, till now, she had lived as happily as a child. Her innocent friendship with Laurie was spoilt by the silly speeches she had overheard; her faith in her mother was a little shaken by the worldly plans attributed to her by Mrs. Moffat, who judged others by herself; and the sensible resolution to be contented with the simple wardrobe which suited a poor man's daughter, was weakened by the unnecessary pity of girls who thought a shabby dress one of the greatest calamities under heaven.

Poor Meg had a restless night, and got up heavy-eyed, unhappy, half resentful toward her friends, and half ashamed of herself for not speaking out frankly, and setting everything right. Everybody dawdled 111 that morning, and it was noon before the girls found energy enough even to take up their worsted work. Something in the manner of her friends struck Meg at once; they treated her with more respect, she thought; took quite a tender interest in what she said, and looked at her with eyes that plainly betrayed curiosity. All this surprised and flattered her, though she did not understand it till Miss Belle looked up from her writing, and said, with a sentimental air,—

"Daisy, dear, I've sent an invitation to your friend, Mr. Laurence, for Thursday. We should like to know him, and it's only a proper compliment to you."

Meg colored, but a mischievous fancy to tease the girls made her reply demurely,—

"You are very kind, but I'm afraid he won't come."

"Why not, chérie?" asked Miss Belle.

"He's too old."

"My child, what do you mean? What is his age, I beg to know!" cried Miss Clara.

"Nearly seventy, I believe," answered Meg, counting stitches, to hide the merriment in her eyes.

"You sly creature! Of course we meant the young man," exclaimed Miss Belle, laughing.

"There isn't any; Laurie is only a little boy," and Meg laughed also at the queer look which the sisters exchanged as she thus described her supposed lover.

"About your age," Nan said.

"Nearer my sister Jo's; I am seventeen in August," returned Meg, tossing her head.

"It's very nice of him to send you flowers, isn't it?" said Annie, looking wise about nothing.

"Yes, he often does, to all of us; for their house is full, and we are so fond of them. My mother and old Mr. Laurence are friends, you know, so it is quite natural that we children should play together;" and Meg hoped they would say no more.

"It's evident Daisy isn't out yet," said Miss Clara to Belle, with a nod.

112 "Quite a pastoral state of innocence all round," returned Miss Belle, with a shrug.

"I'm going out to get some little matters for my girls; can I do anything for you, young ladies?" asked Mrs. Moffat, lumbering in, like an elephant, in silk and lace.

"No, thank you, ma'am," replied Sallie. "I've got my new pink silk for Thursday, and don't want a thing."

"Nor I,—" began Meg, but stopped, because it occurred to her that she did want several things, and could not have them.

"What shall you wear?" asked Sallie.

"My old white one again, if I can mend it fit to be seen; it got sadly torn last night," said Meg, trying to speak quite easily, but feeling very uncomfortable.

"Why don't you send home for another?" said Sallie, who was not an observing young lady.

"I haven't got any other." It cost Meg an effort to say that, but Sallie did not see it, and exclaimed, in amiable surprise,—

"Only that? How funny—" She did not finish her speech, for Belle shook her head at her, and broke in, saying kindly,—

"Not at all; where is the use of having a lot of dresses when she isn't out? There's no need of sending home, Daisy, even if you had a dozen, for I've got a sweet blue silk laid away, which I've outgrown, and you shall wear it, to please me, won't you, dear?"

"You are very kind, but I don't mind my old dress, if you don't; it does well enough for a little girl like me," said Meg.

"Now do let me please myself by dressing you up in style. I admire to do it, and you'd be a regular little beauty, with a touch here and there. I sha'n't let any one see you till you are done, and then we'll burst upon them like Cinderella and her godmother, going to the ball," said Belle, in her persuasive tone.

Meg couldn't refuse the offer so kindly made, for a desire to see if she would be "a little beauty" after touching up, caused her to accept, and forget all her former uncomfortable feelings towards the Moffats.

On the Thursday evening, Belle shut herself up with her maid; and, between them, they turned Meg into a fine lady. They crimped 113 and curled her hair, they polished her neck and arms with some fragrant powder, touched her lips with coralline salve, to make them redder, and Hortense would have added "a soupçon of rouge," if Meg had not rebelled. They laced her into a sky-blue dress, which was so tight she could hardly breathe, and so low in the neck that modest Meg blushed at herself in the mirror. A set of silver filagree was added, bracelets, necklace, brooch, and even ear-rings, for Hortense tied them on, with a bit of pink silk, which did not show. A cluster of tea-rosebuds at the bosom, and a ruche, reconciled Meg to the display of her pretty white shoulders, and a pair of high-heeled blue silk boots satisfied the last wish of her heart. A laced handkerchief, a plumy fan, and a bouquet in a silver holder finished her off; and Miss Belle surveyed her with the satisfaction of a little girl with a newly dressed doll.

"Mademoiselle is charmante, très jolie, is she not?" cried Hortense, clasping her hands in an affected rapture.

"Come and show yourself," said Miss Belle, leading the way to the room where the others were waiting.

As Meg went rustling after, with her long skirts trailing, her ear-rings tinkling, her curls waving, and her heart beating, she felt as if her "fun" had really begun at last, for the mirror had plainly told her that she was "a little beauty." Her friends repeated the pleasing phrase enthusiastically; and, for several minutes, she stood, like the jackdaw in the fable, enjoying her borrowed plumes, while the rest chattered like a party of magpies.

"While I dress, do you drill her, Nan, in the management of her skirt, and those French heels, or she will trip herself up. Take your silver butterfly, and catch up that long curl on the left side of her head, Clara, and don't any of you disturb the charming work of my hands," said Belle, as she hurried away, looking well pleased with her success.

"I'm afraid to go down, I feel so queer and stiff and half-dressed," said Meg to Sallie, as the bell rang, and Mrs. Moffat sent to ask the young ladies to appear at once.

"You don't look a bit like yourself, but you are very nice. I'm nowhere beside you, for Belle has heaps of taste, and you're quite 114 French, I assure you. Let your flowers hang; don't be so careful of them, and be sure you don't trip," returned Sallie, trying not to care that Meg was prettier than herself.

Keeping that warning carefully in mind, Margaret got safely down stairs, and sailed into the drawing-rooms, where the Moffats and a few early guests were assembled. She very soon discovered that there is a charm about fine clothes which attracts a certain class of people, and secures their respect. Several young ladies, who had taken no notice of her before, were very affectionate all of a sudden; several young gentlemen, who had only stared at her at the other party, now not only stared, but asked to be introduced, and said all manner of foolish but agreeable things to her; and several old ladies, who sat on sofas, and criticised the rest of the party, inquired who she was, with an air of interest. She heard Mrs. Moffat reply to one of them,—

115 "Daisy March—father a colonel in the army—one of our first families, but reverses of fortune, you know; intimate friends of the Laurences; sweet creature, I assure you; my Ned is quite wild about her."

"Dear me!" said the old lady, putting up her glass for another observation of Meg, who tried to look as if she had not heard, and been rather shocked at Mrs. Moffat's fibs.

The "queer feeling" did not pass away, but she imagined herself acting the new part of fine lady, and so got on pretty well, though the tight dress gave her a side-ache, the train kept getting under her feet, and she was in constant fear lest her ear-rings should fly off, and get lost or broken. She was flirting her fan and laughing at the feeble jokes of a young gentleman who tried to be witty, when she suddenly stopped laughing and looked confused; for, just opposite, she saw Laurie. He was staring at her with undisguised surprise, and disapproval also, she thought; for, though he bowed and smiled, yet something in his honest eyes made her blush, and wish she had her old dress on. To complete her confusion, she saw Belle nudge Annie, and both glance from her to Laurie, who, she was happy to see, looked unusually boyish and shy.

"Silly creatures, to put such thoughts into my head! I won't care for it, or let it change me a bit," thought Meg, and rustled across the room to shake hands with her friend.

"I'm glad you came, I was afraid you wouldn't," she said, with her most grown-up air.

"Jo wanted me to come, and tell her how you looked, so I did;" answered Laurie, without turning his eyes upon her, though he half smiled at her maternal tone.

"What shall you tell her?" asked Meg, full of curiosity to know his opinion of her, yet feeling ill at ease with him, for the first time.

"I shall say I didn't know you; for you look so grown-up, and unlike yourself, I'm quite afraid of you," he said, fumbling at his glove-button.

"How absurd of you! The girls dressed me up for fun, and I rather like it. Wouldn't Jo stare if she saw me?" said Meg, bent on making him say whether he thought her improved or not.

116 "Yes, I think she would," returned Laurie gravely.

"Don't you like me so?" asked Meg.

"No, I don't," was the blunt reply.

"Why not?" in an anxious tone.

He glanced at her frizzled head, bare shoulders, and fantastically trimmed dress, with an expression that abashed her more than his answer, which had not a particle of his usual politeness about it.

"I don't like fuss and feathers."

That was altogether too much from a lad younger than herself; and Meg walked away, saying petulantly,—

"You are the rudest boy I ever saw."

Feeling very much ruffled, she went and stood at a quiet window, to cool her cheeks, for the tight dress gave her an uncomfortably brilliant color. As she stood there, Major Lincoln passed by; and, a minute after, she heard him saying to his mother,—

"They are making a fool of that little girl; I wanted you to see her, but they have spoilt her entirely; she's nothing but a doll, to-night."

"Oh, dear!" sighed Meg; "I wish I'd been sensible, and worn my own things; then I should not have disgusted other people, or felt so uncomfortable and ashamed myself."

She leaned her forehead on the cool pane, and stood half hidden by the curtains, never minding that her favorite waltz had begun, till some one touched her; and, turning, she saw Laurie, looking penitent, as he said, with his very best bow, and his hand out,—

"Please forgive my rudeness, and come and dance with me."

"I'm afraid it will be too disagreeable to you," said Meg, trying to look offended, and failing entirely.

"Not a bit of it; I'm dying to do it. Come, I'll be good; I don't like your gown, but I do think you are—just splendid;" and he waved his hands, as if words failed to express his admiration.

Meg smiled and relented, and whispered, as they stood waiting to catch the time,—

"Take care my skirt don't trip you up; it's the plague of my life, and I was a goose to wear it."

"Pin it round your neck, and then it will be useful," said Laurie, 117 looking down at the little blue boots, which he evidently approved of.

Away they went, fleetly and gracefully; for, having practised at home, they were well matched, and the blithe young couple were a pleasant sight to see, as they twirled merrily round and round, feeling more friendly than ever after their small tiff.

"Laurie, I want you to do me a favor; will you?" said Meg, as he stood fanning her, when her breath gave out, which it did very soon, though she would not own why.

"Won't I!" said Laurie, with alacrity.

"Please don't tell them at home about my dress to-night. They won't understand the joke, and it will worry mother."

"Then why did you do it?" said Laurie's eyes, so plainly that Meg hastily added,—

"I shall tell them, myself, all about it, and ''fess' to mother how silly I've been. But I'd rather do it myself; so you'll not tell, will you?"

"I give you my word I won't; only what shall I say when they ask me?"

"Just say I looked pretty well, and was having a good time."

"I'll say the first, with all my heart; but how about the other? You don't look as if you were having a good time; are you?" and Laurie looked at her with an expression which made her answer, in a whisper,—

"No; not just now. Don't think I'm horrid; I only wanted a little fun, but this sort doesn't pay, I find, and I'm getting tired of it."

"Here comes Ned Moffat; what does he want?" said Laurie, knitting his black brows, as if he did not regard his young host in the light of a pleasant addition to the party.

"He put his name down for three dances, and I suppose he's coming for them. What a bore!" said Meg, assuming a languid air, which amused Laurie immensely.

He did not speak to her again till supper-time, when he saw her drinking champagne with Ned and his friend Fisher, who were behaving "like a pair of fools," as Laurie said to himself, for he felt 118 a brotherly sort of right to watch over the Marches, and fight their battles whenever a defender was needed.

"You'll have a splitting headache to-morrow, if you drink much of that. I wouldn't Meg; your mother doesn't like it, you know," he whispered, leaning over her chair, as Ned turned to refill her glass, and Fisher stooped to pick up her fan.

"I'm not Meg, to-night; I'm 'a doll,' who does all sorts of crazy things. To-morrow I shall put away my 'fuss and feathers,' and be desperately good again," she answered, with an affected little laugh.

119 "Wish to-morrow was here, then," muttered Laurie, walking off, ill-pleased at the change he saw in her.

Meg danced and flirted, chattered and giggled, as the other girls did; after supper she undertook the German, and blundered through it, nearly upsetting her partner with her long skirt, and romping in a way that scandalized Laurie, who looked on and meditated a lecture. But he got no chance to deliver it, for Meg kept away from him till he came to say good-night.

"Remember!" she said, trying to smile, for the splitting headache had already begun.

"Silence à la mort," replied Laurie, with a melodramatic flourish, as he went away.

This little bit of by-play excited Annie's curiosity; but Meg was too tired for gossip, and went to bed, feeling as if she had been to a masquerade, and hadn't enjoyed herself as much as she expected. She was sick all the next day, and on Saturday went home, quite used up with her fortnight's fun, and feeling that she had "sat in the lap of luxury" long enough.

"It does seem pleasant to be quiet, and not have company manners on all the time. Home is a nice place, though it isn't splendid," said Meg, looking about her with a restful expression, as she sat with her mother and Jo on the Sunday evening.

"I'm glad to hear you say so, dear, for I was afraid home would seem dull and poor to you, after your fine quarters," replied her mother, who had given her many anxious looks that day; for motherly eyes are quick to see any change in children's faces.

Meg had told her adventures gayly, and said over and over what a charming time she had had; but something still seemed to weigh upon her spirits, and, when the younger girls were gone to bed, she sat thoughtfully staring at the fire, saying little, and looking worried. As the clock struck nine, and Jo proposed bed, Meg suddenly left her chair, and, taking Beth's stool, leaned her elbows on her mother's knee, saying bravely,—

"Marmee, I want to ''fess.'"

"I thought so; what is it, dear?"

"Shall I go away?" asked Jo discreetly.

120 "Of course not; don't I always tell you everything? I was ashamed to speak of it before the children, but I want you to know all the dreadful things I did at the Moffat's."

"We are prepared," said Mrs. March, smiling, but looking a little anxious.

"I told you they dressed me up, but I didn't tell you that they powdered and squeezed and frizzled, and made me look like a fashion-plate. Laurie thought I wasn't proper; I know he did, though he didn't say so, and one man called me 'a doll.' I knew it was silly, but they flattered me, and said I was a beauty, and quantities of nonsense, so I let them make a fool of me."

"Is that all?" asked Jo, as Mrs. March looked silently at the downcast face of her pretty daughter, and could not find it in her heart to blame her little follies.

"No; I drank champagne and romped and tried to flirt, and was altogether abominable," said Meg self-reproachfully.

"There is something more, I think;" and Mrs. March smoothed the soft cheek, which suddenly grew rosy, as Meg answered slowly,—

"Yes; it's very silly, but I want to tell it, because I hate to have people say and think such things about us and Laurie."

Then she told the various bits of gossip she had heard at the Moffats; and, as she spoke, Jo saw her mother fold her lips tightly, as if ill pleased that such ideas should be put into Meg's innocent mind.

"Well, if that isn't the greatest rubbish I ever heard," cried Jo indignantly. "Why didn't you pop out and tell them so, on the spot?"

"I couldn't, it was so embarrassing for me. I couldn't help hearing, at first, and then I was so angry and ashamed, I didn't remember that I ought to go away."

"Just wait till I see Annie Moffat, and I'll show you how to settle such ridiculous stuff. The idea of having 'plans,' and being kind to Laurie, because he's rich, and may marry us by and by! Won't he shout, when I tell him what those silly things say about us poor children?" and Jo laughed, as if, on second thoughts, the thing struck her as a good joke.

121 "If you tell Laurie, I'll never forgive you! She mustn't, must she, mother?" said Meg, looking distressed.

"No; never repeat that foolish gossip, and forget it as soon as you can," said Mrs. March gravely. "I was very unwise to let you go among people of whom I know so little,—kind, I dare say, but worldly, ill-bred, and full of these vulgar ideas about young people. I am more sorry than I can express for the mischief this visit may have done you, Meg."

"Don't be sorry, I won't let it hurt me; I'll forget all the bad, and remember only the good; for I did enjoy a great deal, and thank you very much for letting me go. I'll not be sentimental or dissatisfied, mother; I know I'm a silly little girl, and I'll stay with you till I'm fit to take care of myself. But it is nice to be praised and admired, and I can't help saying I like it," said Meg, looking half ashamed of the confession.

"That is perfectly natural, and quite harmless, if the liking does not become a passion, and lead one to do foolish or unmaidenly things. Learn to know and value the praise which is worth having, and to excite the admiration of excellent people by being modest as well as pretty, Meg."

Margaret sat thinking a moment, while Jo stood with her hands behind her, looking both interested and a little perplexed; for it was a new thing to see Meg blushing and talking about admiration, lovers, and things of that sort; and Jo felt as if, during that fortnight, her sister had grown up amazingly, and was drifting away from her into a world where she could not follow.

"Mother, do you have 'plans,' as Mrs. Moffat said?" asked Meg bashfully.

"Yes, my dear, I have a great many; all mothers do, but mine differ somewhat from Mrs. Moffat's, I suspect. I will tell you some of them, for the time has come when a word may set this romantic little head and heart of yours right, on a very serious subject. You are young, Meg, but not too young to understand me; and mothers' lips are the fittest to speak of such things to girls like you. Jo, your turn will come in time, perhaps, so listen to my 'plans,' and help me carry them out, if they are good."

122 Jo went and sat on one arm of the chair, looking as if she thought they were about to join in some very solemn affair. Holding a hand of each, and watching the two young faces wistfully, Mrs. March said, in her serious yet cheery way,—

"I want my daughters to be beautiful, accomplished, and good; to be admired, loved, and respected; to have a happy youth, to be well and wisely married, and to lead useful, pleasant lives, with as little care and sorrow to try them as God sees fit to send. To be loved and chosen by a good man is the best and sweetest thing which can happen to a woman; and I sincerely hope my girls may know this beautiful experience. It is natural to think of it, Meg; right to hope and wait for it, and wise to prepare for it; so that, when the 123 happy time comes, you may feel ready for the duties and worthy of the joy. My dear girls, I am ambitious for you, but not to have you make a dash in the world,—marry rich men merely because they are rich, or have splendid houses, which are not homes because love is wanting. Money is a needful and precious thing,—and, when well used, a noble thing,—but I never want you to think it is the first or only prize to strive for. I'd rather see you poor men's wives, if you were happy, beloved, contented, than queens on thrones, without self-respect and peace."

"Poor girls don't stand any chance, Belle says, unless they put themselves forward," sighed Meg.

"Then we'll be old maids," said Jo stoutly.

"Right, Jo; better be happy old maids than unhappy wives, or unmaidenly girls, running about to find husbands," said Mrs. March decidedly. "Don't be troubled, Meg; poverty seldom daunts a sincere lover. Some of the best and most honored women I know were poor girls, but so love-worthy that they were not allowed to be old maids. Leave these things to time; make this home happy, so that you may be fit for homes of your own, if they are offered you, and contented here if they are not. One thing remember, my girls: mother is always ready to be your confidant, father to be your friend; and both of us trust and hope that our daughters, whether married or single, will be the pride and comfort of our lives."

"We will, Marmee, we will!" cried both, with all their hearts, as she bade them good-night.

X.

THE P. C. AND P. O.

As spring came on, a new set of amusements became the fashion, and the lengthening days gave long afternoons for work and play of all sorts. The garden had to be put in order, and each sister had a quarter of the little plot to do what she liked with. Hannah used to say, "I'd know which each of them gardings belonged to, ef I see 'em in Chiny;" and so she might, for the girls' tastes differed as much as their characters. Meg's had roses and heliotrope, myrtle, and a little orange-tree in it. Jo's bed was never alike two seasons, for she was always trying experiments; this year it was to be a plantation of sun-flowers, the seeds of which cheerful and aspiring plant were to feed "Aunt Cockle-top" and her family of chicks. Beth had old-fashioned, fragrant flowers in her garden,—sweet peas and mignonette, larkspur, pinks, pansies, and southernwood, with chickweed for the bird, and catnip for the pussies. Amy had a bower in hers,—rather small and earwiggy, but very pretty to look at,—with honeysuckles and morning-glories hanging their colored horns and bells in graceful wreaths all over it; tall, white lilies, delicate ferns, and as many brilliant, picturesque plants as would consent to blossom there.

Gardening, walks, rows on the river, and flower-hunts employed the fine days; and for rainy ones, they had house diversions,—some old, some new,—all more or less original. One of these was the "P. C."; for, as secret societies were the fashion, it was thought proper to have one; and, as all of the girls admired Dickens, they called themselves the Pickwick Club. With a few interruptions, they had kept this up for a year, and met every Saturday evening in the big garret, on which occasions the ceremonies were as follows: Three chairs were arranged in a row before a table, on which was a lamp, also four white badges, with a big "P. C." in different colors on each, 125 and the weekly newspaper, called "The Pickwick Portfolio," to which all contributed something; while Jo, who revelled in pens and ink, was the editor. At seven o'clock, the four members ascended to the club-room, tied their badges round their heads, and took their seats with great solemnity. Meg, as the eldest, was Samuel Pickwick; Jo, being of a literary turn, Augustus Snodgrass; Beth, because she was round and rosy, Tracy Tupman, and Amy, who was always trying to do what she couldn't, was Nathaniel Winkle. Pickwick, the president, read the paper, which was filled with original tales, poetry, local news, funny advertisements, and hints, in which they good-naturedly reminded each other of their faults and short-comings.

On one occasion, Mr. Pickwick put on a pair of spectacles without any glasses, rapped upon the table, hemmed, and, having stared hard at Mr. Snodgrass, who was tilting back in his chair, till he arranged himself properly, began to read:—

126

"The Pickwick Portfolio."

MAY 20, 18—

Poet's Corner.

ANNIVERSARY ODE.

Again we meet to celebrate

With badge and solemn rite,

Our fifty-second anniversary,

In Pickwick Hall, to-night.

We all are here in perfect health,

None gone from our small band;

Again we see each well-known face,

And press each friendly hand.

Our Pickwick, always at his post,

With reverence we greet,

As, spectacles on nose, he reads

Our well-filled weekly sheet.

Although he suffers from a cold,

We joy to hear him speak,

For words of wisdom from him fall,

In spite of croak or squeak.

Old six-foot Snodgrass looms on high,

With elephantine grace,

And beams upon the company,

With brown and jovial face.

Poetic fire lights up his eye,

He struggles 'gainst his lot.

Behold ambition on his brow,

And on his nose a blot!

Next our peaceful Tupman comes,

So rosy, plump, and sweet.

Who chokes with laughter at the puns,

And tumbles off his seat.

Prim little Winkle too is here,

With every hair in place,

A model of propriety,

Though he hates to wash his face.

The year is gone, we still unite

To joke and laugh and read,

And tread the path of literature

That doth to glory lead.

Long may our paper prosper well,

Our club unbroken be,

And coming years their blessings pour

On the useful, gay "P. C."

A. Snodgrass.

THE MASKED MARRIAGE.

A TALE OF VENICE.

Gondola after gondola swept up to the marble steps, and left its lovely load to swell the brilliant throng that filled the stately halls of Count de Adelon. Knights and ladies, elves and pages, monks and flower-girls, all mingled gayly in the dance. Sweet voices and rich melody filled the air; and so with mirth and music the masquerade went on.

127 "Has your Highness seen the Lady Viola to-night?" asked a gallant troubadour of the fairy queen who floated down the hall upon his arm.

"Yes; is she not lovely, though so sad! Her dress is well chosen, too, for in a week she weds Count Antonio, whom she passionately hates."

"By my faith, I envy him. Yonder he comes, arrayed like a bridegroom, except the black mask. When that is off we shall see how he regards the fair maid whose heart he cannot win, though her stern father bestows her hand," returned the troubadour.

"'Tis whispered that she loves the young English artist who haunts her steps, and is spurned by the old count," said the lady, as they joined the dance.

The revel was at its height when a priest appeared, and, withdrawing the young pair to an alcove hung with purple velvet, he motioned them to kneel. Instant silence fell upon the gay throng; and not a sound, but the dash of fountains or the rustle of orange-groves sleeping in the moonlight, broke the hush, as Count de Adelon spoke thus:—

"My lords and ladies, pardon the ruse by which I have gathered you here to witness the marriage of my daughter. Father, we wait your services."

All eyes turned toward the bridal party, and a low murmur of amazement went through the throng, for neither bride nor groom removed their masks. Curiosity and wonder possessed all hearts, but respect restrained all tongues till the holy rite was over. Then the eager spectators gathered round the count, demanding an explanation.

"Gladly would I give it if I could; but I only know that it was the whim of my timid Viola, and I yielded to it. Now, my children, let the play end. Unmask, and receive my blessing."

But neither bent the knee; for the young bridegroom replied, in a tone that startled all listeners, as the mask fell, disclosing the noble face of Ferdinand Devereux, the artist lover; and, leaning on the breast where now flashed the star of an English earl, was the lovely Viola, radiant with joy and beauty.

"My lord, you scornfully bade me claim your daughter when I could boast as high a name and vast a fortune as the Count Antonio. I can do more; for even your ambitious soul cannot refuse the Earl of Devereux and De Vere, when he gives his ancient name and boundless wealth in return for the beloved hand of this fair lady, now my wife."

The count stood like one changed to stone; and, turning to the bewildered crowd, Ferdinand added, with a gay smile of triumph, "To you, my gallant friends, I can only wish that your wooing may prosper as mine has done; and that you may all win as fair a bride as I have, by this masked marriage."

S. Pickwick.

Why is the P. C. like the Tower of Babel? It is full of unruly members.

THE HISTORY OF A SQUASH.

Once upon a time a farmer planted a little seed in his garden, and after a while it sprouted and became a vine, and bore many squashes. One day in October, when they were ripe, he picked one and took it to market. A grocer-man bought and put it in his shop. That same morning, a little girl, in a brown hat and blue dress, with a round face and snub nose, went and bought it for her mother. She lugged it home, cut it up, and boiled it in the big pot; mashed some of it, with salt and butter, for dinner; and to the rest she added a pint of milk, two eggs, four spoons of sugar, nutmeg, 128 and some crackers; put it in a deep dish, and baked it till it was brown and nice; and next day it was eaten by a family named March.

T. Tupman.

Mr. Pickwick, Sir:—

I address you upon the subject of sin the sinner I mean is a man named Winkle who makes trouble in his club by laughing and sometimes won't write his piece in this fine paper I hope you will pardon his badness and let him send a French fable because he can't write out of his head as he has so many lessons to do and no brains in future I will try to take time by the fetlock and prepare some work which will be all commy la fo that means all right I am in haste as it is nearly school time

Yours respectably,

N. Winkle.

[The above is a manly and handsome acknowledgment of past misdemeanors. If our young friend studied punctuation, it would be well.]

A SAD ACCIDENT.

On Friday last, we were startled by a violent shock in our basement, followed by cries of distress. On rushing, in a body, to the cellar, we discovered our beloved President prostrate upon the floor, having tripped and fallen while getting wood for domestic purposes. A perfect scene of ruin met our eyes; for in his fall Mr. Pickwick had plunged his head and shoulders into a tub of water, upset a keg of soft soap upon his manly form, and torn his garments badly. On being removed from this perilous situation, it was discovered that he had suffered no injury but several bruises; and, we are happy to add, is now doing well.

Ed.

THE PUBLIC BEREAVEMENT.

It is our painful duty to record the sudden and mysterious disappearance of our cherished friend, Mrs. Snowball Pat Paw. This lovely and beloved cat was the pet of a large circle of warm and admiring friends; for her beauty attracted all eyes, her graces and virtues endeared her to all hearts, and her loss is deeply felt by the whole community.

When last seen, she was sitting at the gate, watching the butcher's cart; and it is feared that some villain, tempted by her charms, basely stole her. Weeks have passed, but no trace of her has been discovered; and we relinquish all hope, tie a black ribbon to her basket, set aside her dish, and weep for her as one lost to us forever.

A sympathizing friend sends the following gem:—

A LAMENT

FOR S. B. PAT PAW.

We mourn the loss of our little pet,

And sigh o'er her hapless fate,

For never more by the fire she'll sit,

Nor play by the old green gate.

The little grave where her infant sleeps,

Is 'neath the chestnut tree;

But o'er her grave we may not weep,

We know not where it may be.

Her empty bed, her idle ball,

Will never see her more;

No gentle tap, no loving purr

Is heard at the parlor-door.

129 Another cat comes after her mice,

A cat with a dirty face;

But she does not hunt as our darling did,

Nor play with her airy grace.

Her stealthy paws tread the very hall

Where Snowball used to play,

But she only spits at the dogs our pet

So gallantly drove away.

She is useful and mild, and does her best,

But she is not fair to see;

And we cannot give her your place, dear,

Nor worship her as we worship thee.

A. S.

ADVERTISEMENTS.

Miss Oranthy Bluggage, the accomplished Strong-Minded Lecturer, will deliver her famous Lecture on "Woman and Her Position," at Pickwick Hall, next Saturday Evening, after the usual performances.

A Weekly Meeting will be held at Kitchen Place, to teach young ladies how to cook. Hannah Brown will preside; and all are invited to attend.

The Dustpan Society will meet on Wednesday next, and parade in the upper story of the Club House. All members to appear in uniform and shoulder their brooms at nine precisely.

Mrs. Beth Bouncer will open her new assortment of Doll's Millinery next week. The latest Paris Fashions have arrived, and orders are respectfully solicited.

A New Play will appear at the Barnville Theatre, in the course of a few weeks, which will surpass anything ever seen on the American stage. "The Greek Slave, or Constantine the Avenger," is the name of this thrilling drama!!!

HINTS.

If S. P. didn't use so much soap on his hands, he wouldn't always be late at breakfast. A. S. is requested not to whistle in the street. T. T. please don't forget Amy's napkin. N. W. must not fret because his dress has not nine tucks.

WEEKLY REPORT.

Meg—Good.

Jo—Bad.

Beth—Very good.

Amy—Middling.

130 As the President finished reading the paper (which I beg leave to assure my readers is a bona fide copy of one written by bona fide girls once upon a time), a round of applause followed, and then Mr. Snodgrass rose to make a proposition.

"Mr. President and gentlemen," he began, assuming a parliamentary attitude and tone, "I wish to propose the admission of a new member,—one who highly deserves the honor, would be deeply grateful for it, and would add immensely to the spirit of the club, the literary value of the paper, and be no end jolly and nice. I propose Mr. Theodore Laurence as an honorary member of the P. C. Come now, do have him."

Jo's sudden change of tone made the girls laugh; but all looked rather anxious, and no one said a word, as Snodgrass took his seat.

"We'll put it to vote," said the President. "All in favor of this motion please to manifest it by saying 'Ay.'"

A loud response from Snodgrass, followed, to everybody's surprise, by a timid one from Beth.

"Contrary minded say 'No.'"

Meg and Amy were contrary minded; and Mr. Winkle rose to say, with great elegance, "We don't wish any boys; they only joke and bounce about. This is a ladies' club, and we wish to be private and proper."

"I'm afraid he'll laugh at our paper, and make fun of us afterward," observed Pickwick, pulling the little curl on her forehead, as she always did when doubtful.

Up rose Snodgrass, very much in earnest. "Sir, I give you my word as a gentleman, Laurie won't do anything of the sort. He likes to write, and he'll give a tone to our contributions, and keep us from being sentimental, don't you see? We can do so little for him, and he does so much for us, I think the least we can do is to offer him a place here, and make him welcome if he comes."

This artful allusion to benefits conferred brought Tupman to his feet, looking as if he had quite made up his mind.

"Yes, we ought to do it, even if we are afraid. I say he may come, and his grandpa, too, if he likes."

This spirited burst from Beth electrified the club, and Jo left her 131 seat to shake hands approvingly. "Now then, vote again. Everybody remember it's our Laurie, and say 'Ay!'" cried Snodgrass excitedly.

"Ay! ay! ay!" replied three voices at once.

"Good! Bless you! Now, as there's nothing like 'taking time by the fetlock,' as Winkle characteristically observes, allow me to present the new member;" and, to the dismay of the rest of the club, Jo threw open the door of the closet, and displayed Laurie sitting on a rag-bag, flushed and twinkling with suppressed laughter.

"You rogue! you traitor! Jo, how could you?" cried the three girls, as Snodgrass led her friend triumphantly forth; and, producing both a chair and a badge, installed him in a jiffy.

"The coolness of you two rascals is amazing," began Mr. Pickwick, trying to get up an awful frown, and only succeeding in producing an amiable smile. But the new member was equal to the occasion; and, rising, with a grateful salutation to the Chair, said, in the most engaging manner, "Mr. President and ladies,—I beg pardon, gentlemen,—allow me to introduce myself as Sam Weller, the very humble servant of the club."

"Good! good!" cried Jo, pounding with the handle of the old warming-pan on which she leaned.

"My faithful friend and noble patron," continued Laurie, with a wave of the hand, "who has so flatteringly presented me, is not to be blamed for the base stratagem of to-night. I planned it, and she only gave in after lots of teasing."

"Come now, don't lay it all on yourself; you know I proposed the cupboard," broke in Snodgrass, who was enjoying the joke amazingly.

"Never you mind what she says. I'm the wretch that did it, sir," said the new member, with a Welleresque nod to Mr. Pickwick. "But on my honor, I never will do so again, and henceforth dewote myself to the interest of this immortal club."

"Hear! hear!" cried Jo, clashing the lid of the warming-pan like a cymbal.

"Go on, go on!" added Winkle and Tupman, while the President bowed benignly.

"I merely wish to say, that as a slight token of my gratitude for the honor done me, and as a means of promoting friendly relations between adjoining nations, I have set up a post-office in the hedge in the lower corner of the garden; a fine, spacious building, with padlocks on the doors, and every convenience for the mails,—also the females, if I may be allowed the expression. It's the old martin-house; but I've stopped up the door, and made the roof open, so it will hold all sorts of things, and save our valuable time. Letters, manuscripts, books, and bundles can be passed in there; and, as each nation has a key, it will be uncommonly nice, I fancy. Allow me to 133 present the club key; and, with many thanks for your favor, take my seat."