#the dynastic state and the army under louis xiv: royal service and private interest 1661 1701

Text

Considerations upon appointments

Louis XIV's brother Philippe, duc d'Orléans- known as Monsieur- was a major asset whom Louis shrank from deploying to full advantage. Philippe had captured Zutphen in 1672 and Bouchain in 1676, before winning a major victory at Cassel in 1677 and following it up with a successful conclusion to the siege of Saint-Omer. Louis was proud of his brother's achievements, even to the point of placing a vast canvas by van der Meulen of the battle of Cassel on the great staircase at Versailles, but he was also horrified at Monsieur's disregard for his own safety. He was henceforth confined to acting as Louis's deputy when they campaigned together, as in 1684 and 1691, though in 1693 he was entrusted with command in western France. Nevertheless, it would be a mistake to see this last appointment as an insult by an insecure elder brother, for in the Nine Years War Louis was consternated by the prospect of an Anglo-Dutch attack on the French coast. He could spare few regular troops for such an eventuality, but instead placed his trust in Monsieur. In the event of an invasion probably only Monsieur (or the king of the Dauphin themselves) could have mobilised the gentlemen of Normandy, Brittany and Poitou in sufficient numbers to make up a force capable of repulsing the Allies when backed by a handful of regular battalions and several regiments of milice. Based at Laval in Mayenne, from where he could rush to any part of the coast, Monsieur was a highly active commander who not only supervised military administration but also repaired major local highways. But his career was also governed by that of his older brother, and when the king retired from active campaigning so too, for precisely that reason, did Monsieur. Considering the duke was still in rude health, though aged fifty-three, with years of invaluable experience behind him, it was a dynastic decision which Louis could perhaps, at the time, ill afford to make.

Louis trusted Monsieur but he could not allow himself to be completely outshone by him. Yet when it came to the Condé Louis revealed all the submerged prickliness and insecurity of his character. Unsurprisingly, at first Louis was reluctant to place too much faith in the Grand Condé who had fought against him for eight years before 1659, and though Condé was more experienced in the Low Countries than Turenne he was not a commander in the first year of the War of Devolution. It would be an error, though, to assume that Condé was brushed aside owing primarily to royal paranoia. Contrary to what has been assumed, his exclusion from command in 1667 was not due to lingering royal resentment, but because, according to the Savoyard ambassador, the money he was owed by Spain, and which was enumerated in the treaty of the Pyrenees, was in arrears, and would be threatened by his participation in an active assault on the Spanish Netherlands. This money was considered necessary because of his likely candidature for the throne of Poland. Later that year, however, Condé was named as commander of the army of Germany, in part so that Turenne would realise he was not indispensable.

Guy Rowlands- The Dynastic State and the Army under Louis XIV: Royal Service and Private Interest, 1661-1701

#xvii#guy rowlands#the dynastic state and the army under louis xiv: royal service and private interest 1661 1701#louis xiv#philippe d'orléans#monsieur#louis ii de bourbon condé#turenne

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

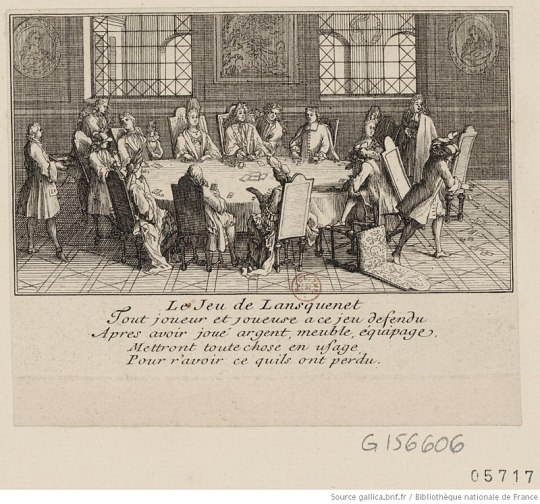

Gambling

Gambling had always been popular with the soldiery- natural risk-takers- for centuries past, but in the seventeenth century it became deeply embedded in French culture more than anywhere else. As Jonathan Dewald has explained, it offered a chance to demonstrate that you were above crude mercantile and financial calculations, it was impersonal, relatively equal and based upon skill and fortune. As such it also offered a safety valve to a society where order and hierarchy were becoming ever more important. The crown made only limited and confused attempts to prevent it, designating games of "hasard"- pure chance- illegal, but permitting and trying to regulate games of "commerce", where intelligence and knowledge were at an equal premium. The most popular examples of each under Louis XIV were bassette and lansquenet; and culbas and reversi. For Jansenists and even mainstream devout Catholics even allowing "jeux de commerce" was too much, not least because gambling was an emotive business which challenged the Great Chain of Being. It bore a heavy responsibility for suicide, murder, duelling deaths and physical degeneration, and even the super-rich were inclined to put their souls in jeopardy by cheating. As if this were not bad enough, it could ruin not just the losers but winners as well and threatened to undermine both royal justice and the codes of honour, for gambling debts could not be pursued through courts of law. Gambling was endemic at court, and some games could involve such huge sums that even the king and royal family had to associate themselves with other courtiers to produce the necessary advances to play. In spite of royal strictures even illegal games were played by courtiers. Furthermore, card games were also played in the War Ministry itself: in the course of my research I found a wine-stained eighteenth-century playing card in a volume of letters at the French war archive- it seems to have been placed there by clerks, or even a minister, to mark a particular piece of correspondence.

The bad example set by the Court was followed by the army officers, many of whom in the higher ranks were of course courtiers themselves. Memoirs and correspondence are littered with references to officers gambling, often in an illegal manner such as playing bassette, reflecting an inability to bring it under control. At the very least innumerable disputes flared up in the course of games, even when they did not lead on to actual violence. More worrying were the financial and psychological consequences of the pursuit. Mme de Sévigné in July 1680 was furious that her son Charles, sous-lieutenant of the Gendarmes Dauphins, had just lost over 3,000 livres at reversi, although the family could afford it. More insidious was the way officers gambled not only with their own pay, but also pledged that of their men as well as promissory notes on the company masse and ustencile entitlement. Hard experience and fear of this happening on a regimental scale led Louis after 1697 to install as majors only men not inclined to gambling. One can hardly blame him, for there were plenty of examples of ruination due to gambling, and financiers' sons in elite units were amongst those forced to sell their posts to pay off debts, so large could they become. Desperate officers short on funds could all too easily turn to gambling as a short-term fix for their cash-flow problems, blotting from their minds the likelihood that it would merely make matters worse and hasten their undoing. Most tragic of all, gambling debts could destroy a man's life a lead him to suicide. At its most extreme competition amongst officers and nobles was clearly even capable of driving them to break one of the ultimate taboos of the age.

Guy Rowlands- The Dynastic State and the Army under Louis XIV: Royal Service and Private Interest, 1661-1701

#xvii#guy rowlands#the dynastic state and the army under louis xiv: royal service and private interest 1661 1701#playing and gambling

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Colbert vs Louvois

Though he was valued by the king, who saw it as both a duty and a necessity to help mould the young man only three years younger than himself, Louvois was politically vulnerable, in part because of a cocksure attitude which stayed with him all his life. Louis apparently had to rebuke Louvois from time to time for his pride and arrogance, even for cheek to the royal person. Louvois's excessive self-confidence and great diligence spawned a corresponding suspicion on the part of Jean-Baptiste Colbert. In the late 1660s Colbert was engaged upon the humbling or removal of ministerial rivals, and he seems to have been set on destroying Louvois as a potential rival as quickly as possible: in July 1666, as the government prepared for war, Colbert launched a savage attack on Louvois in a letter to the king, accusing the young War Minister of ruining France through his arrogance and inexperience. Louis, however, does not appear to have acted upon this vitriolic denunciation, possibly because leading courtiers were making sure the king knew exactly what both ministers were like during these years. When the brief War of Devolution (1667-68) yielded territorial fruit, Colbert seems to have realised that it would not be so easy a task to remove Louvois as it had been to oust Fouquet and Du Plessis-Guénégaud. They consequently settled into an essentially polite, but cold and chary relationship.

Guy Rowlands - The Dynastic State and the Army under Louis XIV: Royal Service and Private Interest, 1661-1701

#xvii#guy rowlands#the dynastic state and the army under louis xiv: royal service and private interest 1661 1701#jean baptiste colbert#françois michel le tellier marquis de louvois#louis xiv#war of devolution

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Colbert vs Louvois

Though he was valued by the king, who saw it as both a duty and a necessity to help mould the young man only three years younger than himself, Louvois was politically vulnerable, in part because of a cocksure attitude which stayed with him all his life. Louis apparently had to rebuke Louvois from time to time for his pride and arrogance, even for cheek to the royal person. Louvois's excessive self-confidence and great diligence spawned a corresponding suspicion on the part of Jean-Baptiste Colbert. In the late 1660s Colbert was engaged upon the humbling or removal of ministerial rivals, and he seems to have been set on destroying Louvois as a potential rival as quickly as possible: in July 1666, as the government prepared for war, Colbert launched a savage attack on Louvois in a letter to the king, accusing the young War Minister of ruining France through his arrogance and inexperience. Louis, however, does not appear to have acted upon this vitriolic denunciation, possibly because leading courtiers were making sure the king knew exactly what both ministers were like during these years. When the brief War of Devolution (1667-68) yielded territorial fruit, Colbert seems to have realised that it would not be so easy a task to remove Louvois as it had been to oust Fouquet and Du Plessis-Guénégaud. They consequently settled into an essentially polite, but cold and chary relationship.

Guy Rowlands - The Dynastic State and the Army under Louis XIV: Royal Service and Private Interest, 1661-1701

#xvii#guy rowlands#the dynastic state and the army under louis xiv: royal service and private interest 1661-1701#louis xiv#françois michel le tellier marquis de louvois#jean baptiste colbert#guerre de dévolution#ministers feud

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Secretary of State for War: the Le Tellier family.

The origins of ministerial government in the western world lay in the transformation of royal private secretaries from the personal aides of a prince into major political players in their own right running fully fledged, if small, departments of state. In the course of the sixteenth century, secretaries of state emerged at the courts of both France and Spain, but by the 1600s these two great powers had diverged in their models of government. In Spain during the later years of Philip II's reign secretarial authority stalled and multiple layers of conciliar government came to prevail, while in England the Privy Council retained a collective importance over and above the relationship between the secretaries and the monarch. In France, however, the secretaries of state, alongside the financial officials, emerged under Henri III and Henri IV as the vital agents of royal executive power, recruited principally from among lawyers and junior councillors. Not least they provided the king with some insulation from the competing influences of the grands, who found themselves increasingly excluded from institutional roles at the heart of government to the benefit of the secretaries. This system, with modifications, was imitated in Savoy from the 1660s and in Spain after 1700.

Initially the responsibilities of French secretaries of state were allocated on a geographical basis, with each one of these four of five officials entrusted with nearly all business related to a particular region of the kingdom. As time wore on they found themselves charged more and more with specific aspects of royal governments, such as the royal household, foreign affairs, or war, but before the 1620s most such divisions were blurred, and only after Richelieu assumed power was there a clearer delineation of responsibilities. The largest ministry in seventeenth-century France- in terms of personnel, expenditure and range of activities- was the Ministry of War which helped the military officers to run the king's land-based armed forces. Over the course of the reign of Louis XIV it became a far more effective instrument for the implementation of royal policy, both at home and abroad. In large part the relative success of this time can be put down to the activity of a single family- the Le Tellier- who occupied the office of Secretary of State for War continuously from 1643 to 1701, an achievement unparalleled by any other ministerial dynasty in any government ministry for the entire ancien régime. Michel Le Tellier was in post from 1643 to 1677; his son, François-Michel, marquis de Louvois, exercised authority jointly with his father from 1664 to 1677 and then on his own until 1691, when he in turn was succeeded by his third son Louis-François-Marie, marquis de Barbezieux. Barbezieux's premature death in 1701 brought the family tenure of ministerial office to an end.

A great deal has already been written about the activity of Michel Le Tellier and Louvois, though very little about Barbezieux, but the literature is heavily skewed towards their institutional reforms and charts the "progress" made during the "personal rule" of Louis XIV, especially in exercising control over the civilian administration of the War Ministry. Few problems thrown up by the king's policies towards the army are mentioned, and the question of the limits of power wielded by the Le Tellier has never, for the period after 1661, been seriously addressed. Moreover, the history of military administration has appeared to lack sufficient context: though some studies have examined the position of the Le Tellier in French society during their tenure of power, historians have tended by and large to treat the family histories of ministerial dynasties as appendages to administrative history: interesting in themselves but somehow not directly related to the government of the realm. Contemporaries in the seventeenth century took a very different view, conceiving politics, especially in monarchies lacking powerful representative institutions, as inextricably bound up with social position and the competition for status. To date the academic literature has seriously downplayed the Le Tellier's power base in the officer ranks of the army and at court as an explanatory took for the successes of the reign. Yet the three successive secretaries depended for much of their power upon their position not only in government, but also in society at large. Louvois and Barbezieux in particular faced powerful enemies within France, and if they were to be capable of enforcing the royal writ then they needed to acquire an entrenched social position which would outlast the skills of any one member of the family [..] There is no need to see the Le Tellier as dishonest to accept that they had interests which sometimes diverged from those of the crown. Indeed, the basic problem which Louis XIV continued to face could be summed up as follows: while Louvois and Barbezieux could usually see what was best to ensure that the king's forces were able to operate most effectively for Louis's needs, the king himself also had to take far greater account of the competing interests of his other ministries, of the finances of his realm, and of the interests of his military officers and non-combatant subjects alike.

Guy Rowlands- The Dynastic State and the Army under Louis XIV: Royal Service and Private Interest, 1661-1701.

#xvii#guy rowlands#the dynastic state and the army under louis xiv: royal service and private interest 1661-1701#henri iii#henri iv#cardinal de richelieu#louis xiv#michel le tellier#louvois#barbezieux#house le tellier#ministers

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Contribution to state-building

As the king knew, ministers contributed to 'state-building' for their own glory, pursuing projects and politics which were not always in his interests and which he sometimes later came to regret. "These ministers all want to accomplish something which will bring honour to themselves in the future," as he told Pontchartrain in July 1698. But on balance the Le Tellier had contributed a great deal to the strengthening of royal authority and the relative stability associated so closely with the first forty years of Louis XIV's "personal rule": Michel Le Tellier deftly worked with Turenne to create a reformed military infrastructure in the crucial years 1654-58; Louvois adapted the system to percolate royal authority deeper through the land forces, in part by an attentiveness to detail which could never have been expected from any one individual, and he developed incentives which helped to tie the military elites firmly to the crown; and Barbezieux cannot be denied a significant part in keeping the machine of state running during the most demanding foreign war France had yet fought. Louvois and Barbezieux in particular were no disinterested bureaucrats but vibrant administrative, military and social politicians. Yet they were instrumental in the reforms of the French armed forces- for good and ill- and the development of a style of management which were emulated in other European states.

Guy Rowlands- The Dynastic State and the Army under Louis XIV: Royal Service and Private Interest, 1661-1701

#xvii#guy rowlands#the dynastic state and the army under louis xiv: royal service and private interest 1661 1701#louis xiv#house le tellier#françois michel le tellier marquis de louvois#barbezieux#does any of you have problems with your tags

1 note

·

View note