#the myth of sisyphus and other essays

Text

there is so much stubborn hope in the human heart.

// albert camus, the myth of sisyphus and other essays

#photography#ph#venice#venezia#italy#travel photography#italia#art#q#quote#albert camus#hope#the myth of sisyphus and other essays#words#writing#europe#real life#travel#photo#poetry#artist#nature#beauty#architecture#view

176 notes

·

View notes

Text

Albert Camus, from The Myth of Sisyphus and Other Essays

Text ID: that irreplaceable voice of the heart,

#albert camus#the myth of sisyphus and other essays#the myth of sisyphus#quote#french literature#lit#existential literature#existentialism#philosophy#miscellanea

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

—Albert Camus, The Myth of Sisyphus and Other Essays

#web weaving#heart#hope#quotes#literature#albert camus#quote#poem#Poetry#words#lit#prose#spilled thoughts#spilled ink#bookworm#bookquotes#books and libraries#dark academia#light academia#aesthetic#academia#typography#chaotic academia#romantic academia#english literature#poems on tumblr#dead poets society#love#life

6K notes

·

View notes

Note

whats your all time favorite book? you may give me other recs too if you'd likee! 💗

I don't have an all time favourite because different books have made me lose my mind in different ways <3 but I CAN give you a breakdown based on some of my own personal categories:

Books I Would Take Into a Bunker For 9 Months (aka Absolutely No One Talk to Me)

The Brothers Karamazov, Dostoevsky

Ich und Du, Martin Buber

The Waves, Virginia Woolf

The Snake, Stig Dagerman

The Myth of Sisyphus and Other Essays, Albert Camus

The Hitchiker's Guide to the Galaxy

An Inventory of Losses, Judith Schalansky

Invisible Man, Ralph Ellison

We, Yevgeny Zamyatin

Books That Did That™️

Secondhand-Time, Svetlana Alexievich

We Love Glenda So Much & Other Tales, Julio Cortázar

The Memory Police, Yoko Ogawa

At Swim-Two-Birds, Flann O'Brien

Deaf Republic, Ilya Kaminsky

Tess of the d'Urbervilles, Thomas Hardy

A Thousand Splendid Suns, Khaled Mattawa

The Chaos Walking Trilogy, Patrick Ness

Ways of Seeing, John Berger

German Autumn, Stig Dagerman

A Lover's Discourse: Fragments, Roland Barthes

A Girl Is A Half-Formed Thing, Eimear McBride

Night Watch, Terry Pratchett

Wuthering Heights, Emily Bronte

Women in Love, D.H. Lawrence

Bluets, Maggie Nelson

Antigone, Jean Anouilh

They: A Sequence of Unease, Kay Dick

A Doll's House, Henrik Ibsen

The Condemned, Stig Dagerman

Books That If I Could Erase My Memory and Read Again for the First Time I Would 100% Erase My Memory and Read Again for the First Time

The God of Small Things, Arundhati Roy

Água Viva, Clarice Lispector

The Bloody Chamber & Other Stories, Angela Carter

A Moth to a Flame, Stig Dagerman

Paris, When It's Naked, Etel Adnan

Without an Alphabet, Without a Face, Saadi Youssef

A Field Guide to Getting Lost, Rebecca Solnit

One Hundred Years of Solitude, Gabriel García Marquez

View with a Grain of Sand, Wislawa Szymborska

Possession, A.S. Byatt

Four Bare Legs in a Bed: Stories, Helen Simpson

The Unbearable Lightness of Being, Milan Kundera

Not to Read: Essays, Alejandro Zambra

The Princess Bride, William Goldman

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

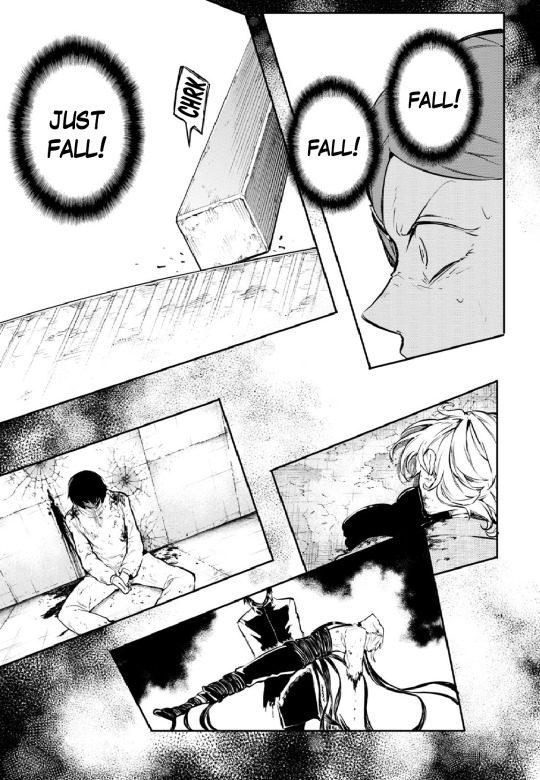

BSD 109 Spoilers!!!

I will always always ALWAYS come back to this panel when talking about Asagiri’s storytelling.

At its very core, BSD is an absurdist text, Kafka Asagiri having been inspired by many absurdist authors. Franz Kafka, who he took his pseudonym from is one of them. Albert Camus, basically the most well-known absurdist is referenced with the Mersault prison, the name of which comes from a character in his most famous absurdist work, The Stranger.

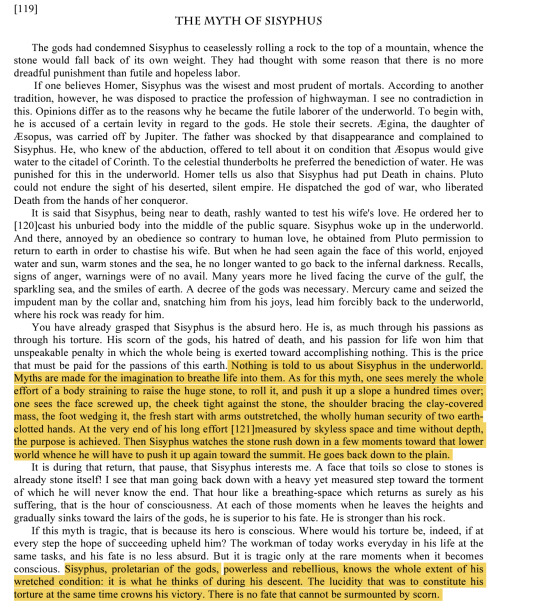

Absurdism is the belief that the world around us is irrational and inherently absurd and that explicitly seeking meaning is pointless. In his essay The Myth of Sisyphus, Camus explains, that there is value in the act of rebellion, though. Sisyphus, who has been doomed to roll a boulder up a mountain only for the boulder to tumble back down each time he reaches the peak, finds meaning in the act of continuing to push the boulder. Even though he will continue this cycle for all of eternity, he doesn’t just lay down and give up, he rebels against the absurdity of his situation by continuing to push the boulder, despite the seemingly futile nature of the act.

As I said earlier, BSD is an absurdist text. All of the animanga’s main characters are on a journey of discovering their meaning in life, and their place in the world, and they do this by rebelling against its absurdity — especially Dazai.

Dazai sees the absurd world for what it is, and when he was in the PM, he hated it. Thus, he sought suicide as a solution. I will note here that absurdists generally view suicide as a failure to rebel against the absurd, just giving up and giving into hopelessness. But ever since Dazai left the PM and took Oda’s advice, he’s been rebelling against this, doing good despite his inherent beliefs about morality and the world, and he’s absolutely gotten better for it.

Other characters embody this idea of rebelling against the absurd, hell, that’s kinda what this whole arc is about. The world is literally ending, and things seem to be at their absolute worst, but someone like Atsushi still has hope that he can change the minds of the hunting dogs and save reality as we know it. He even has hope that he can get through to a vampiric Akutagawa when the guy is literally brainwashed and attacking him. Aya as the “last hope” right now embodies this, too, deciding that she can’t just sit around and do nothing and then trying to remove the sword from Bram even though the effort appears futile.

But everything is going wrong right now. Fukuzawa is bleeding out, Dazai has just been shot through the forehead and appears to have died, Atsushi’s had his limbs ripped off and is at Akutagawa’s mercy, and Fukuchi is literally going to end the world! How can we have hope?!

Think about BSD. Think about the story that’s been told so far. Surely Asagiri isn’t killing everyone right now, surely the world isn’t gonna actually end. I’m not entirely convinced Aya’s plan is gonna work— but please consider that the point of absurdist storytelling is that even when everything seems to be at its worst, even when life seems completely meaningless, there is inherent meaning in still continuing to fight against this.

BSD has never been a story where the villains win, and I don’t think it’s gonna start being one. I think, as usual, Asagiri wants to scare us, to make us feel hopeless about the situation, only for someone to pull through and completely turn the tides.

Dazai laying down and accepting his death at Chuuya’s hands is not going to be the end of his story, because it goes against everything Asagiri seems to stand for. Dazai wouldn’t just give up in his fight against Fyodor, because he needs to prove he’s right about what he says in this panel:

"The ones who actually make the world turn are those who scream within the storm of uncertainty and run with flowing blood."

I think this reflects Asagiri's own beliefs and is also the reason why he is not going to let Dazai die like this, because in a way, that would be proving that Fyodor is right. From a storytelling perspective, it’d be saying “everything I’ve communicated up to this point actually means nothing and life is truly hopeless!”

Dazai has cheated death before, as has basically everyone else in danger right now. I promise you, something is going to happen and they’re all going to survive, because BSD is not trauma porn, for lack of a better term. It’s a story about how a group of people fight against the absurdity of their reality, even when everything seems completely and utterly hopeless.

There’s a lot of theories circulating about how things could work out, especially Dazai’s “death,” and I’m not here to repeat all of them, but I will say that a lot of them have credence, especially because Asagiri isn’t the type of author to make mistakes, every single detail has a distinct reason.

So even though I don't know how things are going to work out, I have full faith that they will, including Dazai's current situation. None of these characters are done just yet, they've got too much fight left in them to just give up.

[original twt thread]

#bsd#bungo stray dogs#bungou stray dogs#bsd 109#bsd spoilers#bsd manga spoilers#bsd meta#kafka asagiri#asagiri kafka#soup rants#being a hashtag camus girlie has its merits!!!#bsd absurdism analysis

866 notes

·

View notes

Text

I am looking inward, You are looking at me.

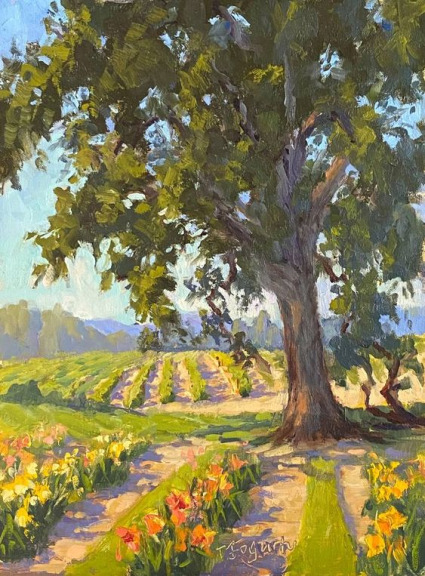

Quote via. @/petfurniture on Twitter | The Dharma Bums, Jack Kerouac | The Myth of Sisyphus and Other Essays, Albert Camus | Nine, Sleeping At Last | The Essence of Hope: His Guiding Light, Randy Burns | Oak Tree Towering Prescence, Tatyana Fogarty | The Brothers Karamazov, Fyodor Dostoevsky | Don't You Wonder Sometimes?, Tracy K. Smith | Quote via. Roland Barthes | The Bug Collector, Haley Heynderickx | The Cottar's Pride - a Cottage Garden, Henry Sutton Palmer | Bitter Herb, Erica Jong | 1884, George Orwell

#web weaving#web weaving poetry#parallels#poetry#prose#humanity#Jack Kerouac#Albert Camus#Sleeping At Last#Randy Burms#Tatyana Fogarty#Fyodor Dostoevsky#Tracy K. Smith#Roland Barthes#Haley Heynderickx#Henry Sutton Palmer#Erica Jong#George Orwell#literature#poemblr#༺✿ web weaves by basil ✿༻

867 notes

·

View notes

Note

hello, your blog's vibes are absolutely impeccable! I was wondering if you could recommend me some nonfiction reading on eroticism, religion or fear? I'd love to read about any of these topics, but I never really know where to start looking for good theory books or essays, so I usually end up reading fiction instead. any nonfiction recs would be deeply appreciated (and on other topics too if you have particular favorites). have a nice day!

hello! thank you for the kind words♡

hm! some reading might be:

- Erotism: Death and Sensuality + Visions of Excess, Bataille

- Masochism: Coldness and Cruelty & Venus in Furs, Deleuze

- The Sadeian Woman: And the Ideology of Pornography, Angela Carter

- Hurts So Good: The Science and Culture of Pain on Purpose, Leigh Cowart

- Eros the Bittersweet, Anne Carson

- A Lover's Discourse, Roland Barthes

- Uses of the Erotic, Audre Lorde

- A Literate Passion: Letters of Anaïs Nin and Henry Miller, 1932-1953

- Foucault's Histor[ies] of Sexuality

- Being and Nothingness, Sartre

- The Argonauts, Maggie Nelson

- Aesthetic Sexuality: A Literary History of Sadomasochism, Romana Byrne

- Pleasure Principles: An Interview with Carmen Maria Machado

- "The Aesthetics of Fear", Joyce Carol Oates

- Recreational Terror: Women and the Pleasures of Horror Film Viewing, Isabel Cristina Pinedo

- "On Fear", Mary Ruefle

- "In Search of Fear", Philippe Petit

- Female Masochism in Film: Sexuality, Ethics and Aesthetics, Ruth Mcphee

- Powers of Horror, Julia Kristeva

- Hélène Cixous' Stigmata (i am thinking esp of "Love of the Wolf")

- Mere Christianity, C.S. Lewis

- anything from Caroline Walker Bynum.... Wonderful Blood, Fragmentation and Redemption, Holy Feast and Holy Fast

- excerpts of Letter From a Region in my Mind, James Baldwin

- Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Nietzsche (re: Christian morality, death of God)

- Waiting for God, Simone Weil

- The Myth of Sisyphus, Albert Camus

- Modern Man in Search of a Soul, Carl Jung

- "The Genesis of Blame", Anne Enright

do know as well that Lapham's Quarterly has issues dedicated entirely to these subjects you've mentioned: eros, religion, fear !

there's also this wonderful ask from @rotgospels on biblical horror theory

other non-fic i will always rec:

- "On Self-Respect", Joan Didion

- Illness as Metaphor + Regarding the Pain of Others, Susan Sontag

- The Art of Cruelty: A Reckoning, Maggie Nelson

- "The Laugh of the Medusa", Hélène Cixous

- Ways of Seeing, John Berger

- The Faraway Nearby, Rebecca Solnit

- The Body in Pain, Elaine Scarry

some non-fic things i've read lately:

- "Mary Shelley's Obsession with the Cemetery", Bess Lovejoy

- "Horror Lives in the Body", Megan Pillow

- "The Cruel Myth of the Suffering Artist", Patrick Nathan

- "The Rub of Rough Sex", Chelsea G. Summers

- "The Lost Art of Memorizing Poetry", Nina Kang

- "The problem with English", Mario Saraceni

317 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Five Stages of Reading Albert Camus

1. The Discovery – ”The Stranger” (1942)

„The Stranger” is unquestionably the best choice for anyone who wants to get to know Albert Camus. It's so simple that it fools you at first. You think it's going to be an easy read, but when you finish the book and put it down, you don't even know your name or if it even matters to have a name. It will probably keep your mind busy for months and make you think about the true meaning of life. You will most likely never be the same person again.

2. Falling in Love – ”Betwixt and Between” (1937) // ”The Fall” (1956) // ”Exile and the Kingdom” (1957)

After "The Stranger" has had time to settle and stick in your mind (a process that takes about six months to a year), it's time to explore other writing. Camus doesn't use the same language in every book, so it's important to be careful what you choose to read after. The best options to fall irrevocably in love with this French philosopher are ”Betwixt and Between”, which is his very first published book, ”The Fall”, which offers a very interesting narrative perspective, or ”Exile and the Kingdom”, his only collection of short stories. After going through these, your heart will be caught in the nets of love for Camus.

3. The Surprise – ”The Plague” (1947) // ”A Happy Death” (written 1936–38, published 1971) // ”Summer” (1954) // ”Nuptials” (1938)

After the reader has gone through the above books, he will have the impression that he knows Camus. Now is the time for him to have the surprise of his life. Camus managed the feat of not giving the audience the same thing twice. That is why each of his writings is unique. Some are easier to read and digest, some are not. At this stage, it is time to get acquainted with its more difficult side. "The Plague" is a story that shakes you to the core and is difficult for even the best readers to get through. ”The Happy Death” should never have seen the light of day, being the first version of what we now know as The Stranger. "Summer" and "Nuptials" are dubbed essays and are similar in format to ”Betwixt and Between”, but here Camus approaches a completely new language, so poetic and refined that it instantly wins you over. Only after the reader goes through these books can he say that he understands a part of Camus.

4. Not just a writer – ”The Myth of Sisyphus” (1942) // „The Rebel” (1951) // Theatre Plays // Journalism Articles

Camus was not only a great French writer. He was also a philosopher (though he never called himself that), a journalist and a playwright. If you are interested in fully understanding Camus, you must also understand his writings in other fields. "The Myth of Sisyphus" is the essay that formed the basis of the formation of a new philosophical current called absurdism. "The Rebel" continues the work started by "The Myth of Sisyphus", going much deeper into the issues related to the meaning of life, art, war, etc. Plays like "Caligula" (1938) or "The Misunderstanding" (1944) are wonderful pieces of art in the history of the theater, while summing up the entire philosophy of Camus. His journalistic articles reveal a Camus involved in society, trying to change something in one way or another through writing. "Reflections on the Guillotine" (1957) for example was an important work that contributed to the abolition of the death penalty in France. Camus never confined his writing to a single specialization, and this can be seen in the skill with which he explored the power of the word in its various forms.

5. Camus the Human – ”The First Man” (incomplete, published 1994) // ”American Journals” (1978) // ”Correspondence (1944–1959)” // ”Notebooks”

At this point, after going through all these readings, we also want to find out who was the man behind the word. Camus put many things from his personal life into writing, but in this selection we have the most personal point of view. ”The First Man” was supposed to be an autobiographical novel, but Camus died before he could finish it. The remaining manuscript was revised and published years after the author's death. "American Journals" captures a highly sensitive moment in his life, an existential crisis in Camus's life. ”Correspondence” is an exchange of letters between Camus and the woman with probably the greatest influence in his life, Maria Casares. Finally, the "Notebooks" are a collection made from the notes that Camus wrote over the years in his countless notebooks. Every intimate thought, beginning of a novel, reflection, trace of feeling, all these complete the image of Camus as a man.

Congratulations! If you have reached this point, you have managed to go through all the stages of knowledge and you can call yourself a true fan of Albert Camus. Now go and spread his teachings to other little outstiders. And don't forget, the only purpose of life is to be happy (reading Camus together).

#albert camus#camus#camus quotes#classic literature#literature#french literature#albert#the stranger#the plague#the fall#exile and the kingdom#20th century#20th century literature#classic authors#a happy death#the first man#betwixt and between#nuptials#summer#the myth of sisyphus#the rebel#philosophy#philosopher#20th century philosophy#absurdism#absurd#existentialism#the theory of the absurd#notebooks#american journals

339 notes

·

View notes

Text

Albert Camus. The Myth of Sisyphus and Other Essays (trans. by Justin O'Brien). New York: Vintage Books, 1991. Translation originally published by Alfred A. Knopf, 1955. Originally published in France as Le Mythe de Sisyphe by Librairie Gallimard, 1942.

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

Everyday Poetry - "In order to understand the world, one has to turn away from it on occasion."

Albert Camus, The Myth of Sisyphus and Other Essays

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Absurdism and Ethics

For those who enjoyed the philosophy of the last post, here's an old thesis I did.

When one contemplates Camus’s philosophy of the Absurd, often times the argument ends at the physical act of living. It seems reasonable that the question posed is whether or not life is worth living on the individual level when faced with our own cosmic insignificance in an uncaring world. However, once one sorts their way past this obstacle of existence and radical freedom, Camus’s philosophy seems to break down. Not in the way that his philosophy no longer holds water, but that the means of explaining such a subjectively universal experience as Living is fraught with intersectionality and contradictions. It is then of little surprise that the best way Camus found to connect these ideas in even a remotely understandable manner was through his topic of the Absurd Man. Instead of trying to reason out his philosophy to the individual, he expressed his thoughts in the form of three distinct characters, not necessarily separate but, like the Christian Trinity, each having their place and role to play in the greater world of absurdity. For life is absurd, and every man living must live in absurdity, to do so he must body the characters of Camus’s actor, the Don Juan, and the conqueror. Unsurprisingly, it is that last one that garners the most repulsion of our modern society and, of this, Camus is aware. We each would aspire to think of ourselves as somehow above the rabble of domination; that we have reached a higher existence through some morality that rejects such barbarism. Camus instead insists that humans have barely come to terms with their own inconsequential existence, let alone the complexities of the other Self and relation to it. As thus it isn’t the practice of the Absurd that creates these contractions, but the selfish rejection of it.

In his essay “Accepting the Absurd”, Kurt Blankschaen turns to Sartre, “because Camus minimally describes how the Absurd enters into our life” (Blankschaen 29). This statement fundamentally misses the point of Camus’s integration of the Absurd Man within his argument. Camus says, “The absurd man begins where that one leaves off, where, ceasing to admire the play, the mind wants to enter it” (Camus, The Myth of Sisyphus 77). Blankschaen admits, “Camus is very careful to point out the Absurd is not a thing in the world, but rather is simply a relationship between humans and the world” (Blankschaen 39), which clearly delineates the perspective of his approach with Sartre. He spends a great time highlighting how “Sartre’s work casts the Absurd as something to be rejected or endured” (Blankschaen 38), and “Sartre is quite right to highlight this emotive resistance or disgust towards the Absurd” (Blankschaen 39). It is fair to remember, however, that Blankschaen seems to be arguing the literal “entering” of the Absurd into one’s life: the initial moment of one becoming aware of the Absurd in our world and not necessarily the implications of what it means to actively live in Absurdity. However, in his following comment that “One possible objection to Camus might be that some people just never really encounter the Absurd” (43), he misses the fact that the actor of the Absurd is the vehicle in which Absurdity is practically related. Art and creativity has always been a form of play, hardwired into human brains as a means of fast and efficient learning and, according to Camus, the artist is inherently absurd. It is fundamentally impossible, then, for one to never be encountered with Absurdity, for everyone has encountered their own experience of the subjectivity of art and its meaning. Camus expands on this concept in both life and art through his novel The Stranger.

Thomas Pölzler writes, “The problem is that Camus’s early philosophy appears to be essentially inconsistent” (“Absurdism as Self-Help” 91). His essay cleanly dissects the two branches of argument Camus makes in The Myth of Sisyphus by stating, “[the philosophy] seems to be based not only on the denial, but the affirmation of moral values” (Pölzler 95) entirely missing the point that this perceived contradiction is not a problem at all. He continues to say, “The things I take Camus to regard as good or praiseworthy are mainly character traits” (Pölzler 95) while pointing out Camus’s belief that meaning implies a scale of value, not quite realizing he is implying an inverse equation to the logic. He begins his essay with the criticism of Camus by other scholars calling the philosophy too “simple to be taken seriously” (Pölzler 91), but falling as well to the same logical fallacy of that argument. Camus states a belief in meaning implies value, not value implies meaning. In fact, this rhetorical concept is reinforced by Blankschaen’s misguided assessment of the Absurd when he states “…Sartre’s position towards the Absurd …prioritizes choice” (Blankschaen 39). In fact, Sartre was not merely complimenting Camus in his works, but embracing the Absurd completely: To value is to choose to elevate, but a belief of an inherent meaning is to value without choice, asking thus if there is value at all. Conversely, one could ask if meaning is to imply value, is there value in the meaningless? For Pölzler to label Meursault from The Stranger an “individualistic nihilist” (is to discredit the character’s value in meaninglessness and an active avoidance of seeking value in it. To some, Meursault could be perceived as the embodiment of the blackhole that meaninglessness signifies, yet the first half of the novel does not make Meursault anyone special. Camus perfectly embodies the dull normality of living every day that makes up the universal human experience. Both Blankschaen and Pölzler skip over this aspect of Absurdity and, instead, focus on the cosmic end of it all that closes out the novel. They both insist that everything is meaningless only because of the inevitability of death and not the reality that, even in life, meaning is purely subjective and thus an illusion to begin with.

Camus addresses this concept in the most abstract of ways through his take on Don Juanism. It could be said Camus himself gets derailed by his ideas involving the character of Don Juan in his essay explaining the absurd man. Trying to relate his philosophy to the titular character while being weighed down by his own argument against love, it is easy to get lost in the weeds of the debate. However, the breadth of the matter is isolated in his observation that, “People are sufficiently annoyed (or that smile of complicity that debases what it admires) by Don Juan’s speeches and by that same remark that he uses on all women” (Camus, The Myth 71). Camus acknowledges the fact that Don Juan is a polarizing individual, but it is the fact he is polarizing that makes him the absurd man. Pölzler argues Camus’s absurdity is contradictory while Camus argues that Absurdity is the contradiction. Pölzler even acknowledges this when praising The Rebel when this facet has been the foundation of the philosophy since the beginning.

Breaking down specifically what Camus is stating, he highlights the “complicit smile that debases what it admires”. It is easy to deconstruct then, that the complicity comes from deriving enjoyment from Don Juan’s antics. Most would agree that being a womanizer is not something one should be proud of when projecting the idea of meaning onto things like love and sex. Camus asks, “Why should it be essential to love rarely in order to love much?” This is a question then, not of meaning, but of value. “‘At last? No’ he says, ‘But once more '” (The Myth 69). Camus is directly showing the failure of Pölzler’s critique: Meaning implies value, just as the diamond ring is worth thousands despite not being all that rare, the meaning behind giving a diamond keeps the prices exorbitant. However, the practicality of reselling the diamond is null. While it has value for its physical use, one will never make back the perceived value of the meaning they already spent. The value is objectively absolute, the meaning is arbitrary.

That then begs the question, where does this concept of meaning that Camus stands contrarian to originate? Camus states that “The absurd … does not lead to God”, however, he ties the two together by stating “the absurd is sin without God” (The Myth 40). So when discussing the absurd, the rejection of meaning is less the topic of subjectivity and that of a divine one. In The Will to Power, Nietzsche says on the topic of Divine morality, “The values of the weak are [leading the way], because the strong have adopted them in order to lead with them” (299). This concept finds its home within Camus’s conqueror, which, as the name implies, houses the philosophy that power is the sole truth of living. In fact, Nietzsche argues that God and the divine are mere fictions created by society’s helpless, whom he considers the “slave” class when he writes, “Slave-morality is essentially the morality of utility. Here is the seat of the origin of the famous antithesis ‘good’ and ‘evil’” (Good and Evil 231).

Nietzsche spent the majority of his writings on this very concept of power behind the divine and how western society is rooted in this single fact, yet it is still a revolutionary concept today. Only in the last decade has it been acknowledged that Western powers have, and still do, utilize missionaries as a means of spreading influence to other lands. From the Crusades, to America’s Manifest Destiny, to the British Empire, all were built upon the idea of a God given right and order to spread these constructs across the globe, dominating cultures and peoples through assimilation or destruction. The Divine is drenched in centuries of war and genocide, which Nietzsche, in the 1800s, identified as an avenue for conquest and an outlet of cruelty. Many infer a sense of judgment behind Nietzsche’s works, but it is fairer to say that his writings are less an instruction and merely an objective fact of human society. He writes, “Man has one terrible and fundamental wish; he desires power, and this impulse, which is called freedom, must be the longest restrained. Hence ethics has instinctively aimed at such an education as shall restrain the desire for power” (The Will 185).

Both Nietzsche and Camus acknowledge Christianity as a prominent landmark in their contemplations of reality. For centuries, the concept of life and the cosmic reason for its existence was so intrinsically woven into faith that any other answer was grounds for execution. In this way, society, and thus humanity and the ethics that define it, cannot be separated from faith and its morality. As such, Camus presents the Absurd, not as a denouncement, but as a mirror to Ethics. In practice, the tenants of the Absurd Man are the direct equivalents to the Holy Trinity. The actor is the way of relating to the absurd just as the Holy Spirit is how God supposedly influences his Christian followers. The conqueror is the truth of life itself, the root of all motivation in humanity, just as how God is the origination of all things. That then leaves the Don Juan figure, or its equivalent, as the Messiah, the son of man walking in complete harmony with truth and enlightenment. Camus’s novel, The Stranger, thus acts as the gospel of the Absurd through the life of Meursault.

In his efforts to simultaneously clarify his explanation of the Absurd and also challenge our perception of a moral reality, Camus tells his story of an Absurd Hero with no hero’s journey. On the surface, Meursault is a man of little constitution who, seemingly, stands for nothing. He befriends a man who hits women while being an affectionate partner to Marie. He lacks the expected empathy for Salamano’s dog, only to invite Salamano into his room and listen to him talk about said pet. All the while openly not being interested in anything the old man has to say but listening intently enough regardless. Meursault is a generally agreeable man, not seeking conflict nor with a rude disposition, and yet is responsible for murdering a man who was guilty of being in the wrong place at the wrong time. It seems almost inherent that one would find such a man impossible to relate to, but Camus takes great pains to properly lay the foundation of what Meursault is when he writes, “For want of anything better to do, I picked up an old newspaper that was laying on the floor and read it. There was an advertisement of Kruschen Salts and I cut it out and pasted it into an album where I keep things that amuse me in the papers. Then I washed my hands and, as a last resource, went out on the balcony” (The Stranger 15).

Meursault is the definition of the Everyman, plagued with a limitless boredom that fuels an unending desire to escape it: The quintessential human experience. There is no assertion of individualism, rather, despite being positioned above the main street and privy to all the happenings of the city inhabitants as a god on high, there is the same benign indifference he holds towards his own existence and his only reason for bearing witness unto it is pure apathy. Meursault is a simple man and knows himself as such when he says, “I explained that my physical condition at any given moment often influenced my feelings'' ( Stanger 41). This is his one solid truth, justified by his previous actions when he writes, “Marie looked hard at me. Her eyes were sparkling. I kissed her'' (Stranger 24). The same equation is in play during the lead up to the murder when he says, “The heat was beginning to scorch my cheeks … and I had the same disagreeable sensations — especially in my forehead where all the veins seemed to be bursting through the skin” (Stranger 38). Meursault simply is what he does, spurred on by something as fleeting as a “sensation” that rests upon a foundation of an almost passive observance to his own existence. In fact, this itself is what Camus is arguing: It is impossible to contradict oneself when there is only one truth in the universe.

Camus’s quote through Meursault “[My employer] then asked if a ‘change of life’ didn’t appeal to me, and I answered that one never changed his way of life; one life was as good as another” (Stranger 28) is echoed in his response to Marie when she asks if he loves her, “I said that sort of question had no meaning, really” (Stranger 24). Meursault is not saying that the question is pointless or that life is without value, but that it is meaningless. What does it matter if he lives his life in Algier or Paris? His life in France would likely be the same, just in a new place. What does it matter if he says he loves her or he doesn’t? He has sensations of desire and even adoration for Marie, so he acts upon them. What does it matter if it is love or not if they are both finding happiness in the arrangement?

It is not that love does not exist, but that the meaning of Love that society has given it is so indefinable and contradictory that to say “I love you” is meaningless. This is why the story of Salamano and his dog is so important to The Stranger. Camus introduces Salamano to the reader through the venue of his abuse towards his pet. How brutish he is and the expectations he has for the animal to be unrealistic and contradictory, only for his “love” to be laid bare after the dog runs away. His cruelty is in equal measures to his kindness, raising the puppy by bottle and having done all he could through medicated baths to soothe the dog’s diseased skin. There is no mistaking that the relationship portrayed between the man and his pet is an allegory for marriage, Camus makes this as obvious as possible through the narrative that the dog was a literal replacement for Salamano’s deceased wife (Stranger 30). Love, is merely a tedious dance poised on this expectation of shared beliefs called ethics, with no existence of the absolute it holds claim to.

The reality that this shared expectation is the issue at argument comes most prominently in the case of Meursault’s trial. Sometimes referred to as a Kangaroo Court, often understood as a rigged trial held in order to judge someone regarded, especially without good evidence, as guilty of a crime, Meursault’s trial is not without good evidence. As a matter of fact he readily admits to the murder, so his guilt is without question and evidence is unnecessary to acquire. It isn’t a trial on whether or not Meursault committed the crime of taking a life, or even what his punishment should be for such an act. In fact, Meursault sits on trial and is subsequently sentenced to death for amorality, or rather, not living in union with the ethics of society.

Every aspect of interpersonal relationships dangles by this thread of shared beliefs. It is often the underlying sense of subtext that causes the most conflict as we insist to understand in a world that functions on smoke and mirrors; to be accepted and succeed within society is to play by these unspoken rules. Of this, Camus says, “There, too, are several ways of committing suicide, one of which is the total gift and forgetfulness of self” (The Myth 73). Camus directly argues here that to surrender to these expectations is metaphysical suicide, that it is a form of non-participation in life. This compliments Nietzsche when he wrote, “All motive force is the will to power; that there is no other force, either physical, dynamic, or psychic” (The Will to Power 162). To deny the desire for power, no matter how small, is to deny the act of living, but to live free of the chains of Ethics results in those confined inside to reject the individual and devalue the existence of morality itself. When Meursault rejects the suicide offered him by the Magistrate, he asserts his own morality outside of Ethics, that of Authenticity. It is why Meursault says he “[hoped] … on the day of my execution there would be a huge crowd of spectators and that they should greet me with the howls of execration” (The Stranger 76)

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Albert Camus, from The Myth of Sisyphus and Other Essays

Text ID: How can one fail to realize that in this vulnerable universe everything that is human and solely human assumes a more vivid meaning?

#albert camus#the myth of sisyphus and other essays#the myth of sisyphus#quote#philosophy#existential literature#existentialism#absurdism#french literature#lit#miscellanea

868 notes

·

View notes

Text

the lifts in the fulton building are out of service

i had a lecture today that was upstairs in one of the buildings on my uni campus and the lifts were all out of service.

i broke down into tears. a year ago i would have been able to face the pain, i would have been able to make it but that is just not an option anymore.

my pain is slowly getting worse and worse and i am only 19. i am lucky to have wonderful supportive friends who help me as much as they can but i cannot help but feel like a burden. there is so much inescapable grief in being disabled and having chronic illness. i grieve my health, i grieve my inability to do so many things i watch others do with ease. i cannot even cook my own food or do dishes most of the time. it hurts more than just physically, i feel violently wounded by my body's genetic makeup, by the very fibre of my being. i am rotting. i am not well, i will never get better and i will never be okay in any meaningful sense of the word. it hurts. most of the time i just take it day by day and i am positive about it as there is still so much joy and love and fulfillment in my life. but today even as i type this out on my laptop my arms ache and i am swallowed by the bleakness and isolation of it all. i want to be well. i want to be able to attend my lecture. this is not the plan. none of this was the plan. my whole body hurts constantly. i pass out all the time. i am always overheating or ice cold, always existing in extremes. i have started dislocating more frequently. a lot of my teeth are going to fall out. i've already lost two. i am so tired all the time. no matter how much i sleep. there is so much. it is all so much. i will persist and this wave of grief will wash over me and there will be calm and joy once again despite the pain, until the next wave of grief hits. we have been studying camus' essay on the myth of sisyphus and he says that one must imagine sisyphus happy as he is fated to roll that rock up the hill again and again ad infinitum. i imagine sisyphus grieving. grief and love are the same emotion, grief is just love with no outlet, when there is no space to put it. i imagine sisyphus happy and filled with love but i also imagine him filled with sorrow and grief.

i hope they fix the lift soon.

#camus#absurdism#chronic illness#chronic pain#chronic fatigue#chronically ill#pots#ehlers danlos syndrome#hypermobile ehlers danlos#ehlers danlos zebra#ehlers danlos problems#mcas

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think the fact that in the song 'Achilles come down' that depicts the scene of Greek mythology hero Achilles, that is known to have the one of the most tragic stories, contemplating s*icide on the roof of a building while fighting his own inner monologue, contains quotes and passages from Albert Camus's 'myth of Sisyphus' essay on s*icide and in french after the verses, is probably my fav fact.

one of the quotes is "je vois que beaucoup de gens meurent parcequ'ils estiment que la vie ne vaut pas la peine d'être vécue. j'en vois d'autres qui se font paradoxalement tués pour les idées ou les illusions qui leur donnent une raison de vivre"

which translates to "I see many people die because they judge that life is not worth living. I see others paradoxically getting killed for the ideas or illusions that give them a reason for living."

#songs#achilles#achilles come down#greek gods#greek mythology#albert camus#the myth of sisyphus#french literature#philosophy#quotes#alber camus quotes#gang of youths#Spotify

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

What is absurdism/the philosophy of the absurd?

I talk a lot about absurdism and how BSD can be read as an absurdist text, but I recognize that not everyone fully knows what absurdism as a philosophical principle or literary device actually is. So rather than explaining it every single time I bring it up, I figured I'd write a brief overview!

People often assume that when we talk about something being "absurd," that we're referring to the most commonly used definition of this word: "ridiculously unreasonable, unsound, or incongruous." While this certainly applies to a certain extent, the more accurate defintion of the adjective in the context I talk about it is this: "having no rational or orderly relationship to human life: meaningless." In this case, I find the the noun definition to be most precise: "the state or condition in which human beings exist in an irrational and meaningless universe and in which human life has no ultimate meaning" (all definitions from Merriam-Webster).

Put simply: when I talk about the absurd and absurdism, I'm not simply referring to the fact that things are crazy or weird, but rather to the fact that they are nonsensical in relation to life and life's meaning. This is what is at the core of absurdism.

So what is absurdism, exactly? Merriam-Webster defines it as "a philosophy based on the belief that the universe is irrational and meaningless and that the search for order brings the individual into conflict with the universe."

Existentialism contends that humans are responsible for creating their own meaning, absurdism is a branch of this school of thought that argues that meaning is created through rebellion against the absurd.

Albert Camus was a French philosopher and author who is often considered the father of absurdism as a philosophical principle. In his essay The Myth of Sisyphus, he compared human life to the greek myth of Sisyphus, who was cursed to roll a boulder up a mountain only for it to roll back down once he reached the peak, forcing him to start over -- a cycle that goes on for eternity. Sisyphus' mere existence is seemingly meaningless, but Camus argued that Sisyphus gives his own meaning to the absurd situation forced upon him simply through the act of the struggle -- his choice to continue pushing the boulder despite the circumstances has value.

Rebellion and revolt are at the forefront of absurdism, as the other options offered are incapable of giving life meaning, according to Camus. If one simply gives in to life's absurdity, becoming a part of the system rather than challenging it, then this accomplishes nothing and means you have trapped yourself within absurdity. The other option is suicide, which Camus also views as "giving in" to absurdity, since the individual succumbs to the idea that life has no worth. Acts of rebellion, on the other hand, give life meaning because you have something to fight for/against.

Often, the mode of rebellion assumed by the absurdist is more absurd than the world itself. This is a really niche example, but I think it explains this well: During the communist regime in the then Czech Republic, revolutionary Vaclav Havel was followed by police when he was on vacation, constantly being spied on and sometimes attacked for no reason. Havel's response? He invited his stalkers in for tea.

What an absurd reaction to an absurd situation! But nevertheless it was an act of resistance, because Havel was directly acknowledging that he was being constantly spied on for no good reason, breaking the unspoken rule of not acknowledging those spying on you. He knew that there was no point in trying to avoid them (doing so would only arouse more suspicion of him), so instead he embraced the absurdity of his situation. Often, an act of revolt entails doing just this.

In literature, whether the absurdist protagonist succeeds in their rebellion often depends on how pessimistic the author is. Franz Kafka, for example, ended most of his narratives in his main character dying in their act of rebellion, mirroring how in the real world things aren't always fair (an absurdity within itself). Camus was a bit more hopeful, his protagonists often surviving, but not always happily. Even in the case of death, though, it is implied that there is more meaning in having rebelled and died, than having continued living without a purpose.

Additionally, I want to briefly highlight that bureaucracy a big, fat absurdity that authors tend to critique. "The powers that be" often do not make sense and have priorities that don't align with commonly accepted human morals. Capitalism, government, military, police, and law are various institutions/ideas that are often criticized by absurdist authors for this reason. Franz Kafka wrote the story of a man sentenced to death without trial for a crime never detailed to him. Camus wrote the story of a doctor dealing with a plague outbreak that happened because officials didn't want to name the disease as plague and scare the public. These are just a few examples of many from the absurdist authors I am familiar with.

So, that's my brief overview of absurdity! I think it tends to pop up in a lot of fiction nowadays because of the relatable idea that things feel senseless paired with the hope that there's meaning in the act of pushing back against such things -- it makes for a good story!

I didn't cover anything and everything here because I wanted to be concise, but I think this is a good foundational understanding of the principle to move forward with. Who knows, you might start recognizing the absurd in your favorite piece of fiction... or even in real life!

#absurdism#the philosophy of the absurd#albert camus#franz kafka#literature#philosophy#bsd#soup rants

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

I just realized that when I was like 14 or so I was reading some book called "The Myth of Sisyphus and Other Essays" and

who is doing this

#what's it trying to sell#a sense of mystery and awe#so it can be marketed towards teenagers?#computer generated image#guidance scale 2#guidance scale 1 (text-heavy images)

28 notes

·

View notes