#there are a lot of oversimplifications in here and there are exceptions to the rules all over the place

Text

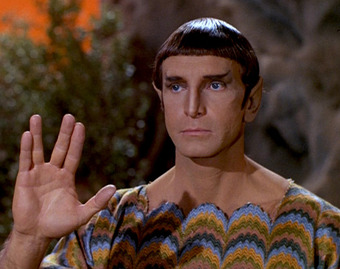

One thing that bugs me about the way Vulcans are usually depicted (with some lovely exceptions) is that their philosophy—logic, or the teachings of Surak, for short I'm just going to call it Surakianism—is very often shown as a bad thing. Either that, or Vulcans aren't following it at all.

Writing about religion (and I do think Surakianism is best approached as a religion*) is always fraught. Because generally as a writer, you don't actually practice the faith in question, so naturally you'll have an outside view. That's doubly true of Surakianism, a way of life humans basically can't follow and it would probably be bad for us to try.

[*I know they don't call it a religion. But the way it deeply affects the interior life of Vulcans, their ethics, and so on feels very religious to me. It doesn't seem to have a position on theism; Vulcans get their beliefs about god(s) from elsewhere, such as traditional Vulcan polytheism and their own perceptions of the universe. But the way it exists as a social structure AND a guide to the inner self is absolutely religious to me.]

We are told that Vulcans developed this philosophy specifically because they needed it—they were destroying themselves without it! Their emotions were overpowering and violent, and they were clannish to the extreme. So despite what most of the human characters say, especially Bones, I think the path of logic is a good thing for Vulcans, even if humans don't get it at all.

Surak's teachings can be summed up into three basic points (a Vulcan somewhere just raised an eyebrow clear into their bangs at this oversimplification, but I'm doing my best here):

1. Logic, or the use of reason as a guide and the control of emotions

2. Nonviolence

3. IDIC—infinite diversity in infinite combinations.

Of course we only ever hear about the first one, because that's part humans notice. I'd say it was like reducing Catholics to fish Fridays and Mormons to underwear, but that's exactly what people do, so I guess it's understandable.

But I think the ordering goes the other way for Vulcans. First, acknowledge that others are of value, including and especially when they're different from you. Then, do them no harm. And finally, to achieve that goal, control your wild, violent emotions.

People imagine pre-reform Vulcans a lot of ways (and I never get tired of reading about them), but I think the best guide as to what they're like is by looking at Romulans. Romulans aren't wildly expressive with their emotions, we're certainly not talking about people who would otherwise be laughing and crying constantly. Instead, they're secretive and carry long, hateful grudges. They're loyal only to those closest to them, and they seem entirely without empathy otherwise.

Imagine the Vulcan emotions are like that. They have strong bonds to their clan, probably in part because of their telepathy. They're suspicious of outsiders, angry, prone to violence. Preferring the familiar is an instinct in humans too, but a mild one. Certainly humans have been and still are racist, but it's something we can generally overcome. I'm not sure the Vulcans could, not by relying on their emotions.

So they came up with the solution to control their emotions completely. Use reason instead as a guide to behavior, because logic will tell you that your own clan is not more important than another, and that reaching out in peace is beneficial to yourself and others. Don't give your emotions any credence and don't let them run wild.

Humans do some of this ourselves, and should arguably be doing more. We spend a huge chunk of our childhood learning to control antisocial impulses like screaming, hitting, and biting. We demonstrate self control in many tiny, unnecessary ways, in order to show to others that we are in control of ourselves: stuff like etiquette, social rules, even just leaving the last cookie on the tray for someone else. These are signals that say I am not governed by my appetites; I can be trusted to consider the needs of others.

And we could obviously be doing more. Too many political questions are being answered by people's emotional, knee-jerk responses like "I feel threatened by people who are different" or "I am angry about my enemies and want them punished" instead of "what produces the most benefit for everyone?" If we leaned more heavily on logic and reason to get us our answers, we'd make way better decisions than we do. Star Trek doesn't often acknowledge that in real life, making a snap gut decision doesn't actually have a very high success rate. Logic gives you better odds of saving the day.

But, you might say, Vulcans aren't doing very well at any of this. A heck of a lot of them that we've seen are racist. And while they repress their emotions just great, they don't actually make the most logical decisions most of the time.

But I don't think this actually discredits a religion at all. We all know Christians who are great at the easy parts of their religion—learning Bible verses or saying rosaries—but don't seem to be even trying to love their neighbor. That's in fact the way religions are usually practiced! External elements that people can easily see (like never smiling) are adhered to by social pressure, but more heart-level things are aspirational at best. That doesn't mean the message of a religion is bad; it doesn't really tell us anything.

This is especially true for a religion whose practice isn't optional. You have to follow Surak to stay on the planet. I can see this rule was necessary during the time when the Romulans were kicked out—pacifism doesn't work as a global solution unless everybody's doing it. Now, it seems a bit harsh. I think they get around it by not exiling anybody who's at least giving lip service to logic. That racist baseball guy in DS9 isn't a good Vulcan, but as long as he doesn't do anything violent or openly reject Surak, they're willing to say he counts.

Why are Vulcans so often the opposite of what their religion teaches? I think it's the other way around: their religion focuses specifically on their chief faults: clannishness, racism, ego. It just hasn't successfully transformed everyone. Makes perfect sense, really. We might as well ask why Christianity goes on and on about sex when humans are well known to be super obsessed with sex. Well that's WHY! It's one of our strongest impulses which in the past we felt the most desperate need to control.

The best argument against Surakianism is that total repression isn't the best way to handle emotion, that we need self-awareness of our emotions before we can account for them.

To which all I can say is, don't you think Vulcans know that?

I imagine there are lots and lots of viewpoints on this among Vulcans. Some favor repression and some favor understanding and acceptance; some think it's okay to have a little dry humor and some think we should be serious. We have the kolinahri who believe in the excision of all emotion (which I imagine is universally seen as extreme, like we might see cloistered nuns or monks who reject the world to achieve enlightenment). And surely there are ancient, wise Vulcans who deeply understand all their emotional impulses and are completely in control of them. Spock certainly seems this way by the movie era if not before: he knows that he has emotions, what they are, and how to respond to them. He has overcome the emotion of shame. So he seems not impassive on the outside, but a person at complete peace inside and out.

I just feel like we could stand to see more good Surakians, who are good not in spite of their belief in logic, but because of it. Kind of like how we see both good and bad followers of the Prophets on Bajor. I'm kind of anti religion myself, but I still want to see it given its due—especially a religion founded on such good principles. Sure, it's not a religion humans can really practice, nor need—a good half of our emotions are positive and pro-social, so it's no wonder a person like Bones would be convinced Vulcans are just punishing themselves unnecessarily. But it successfully turned Vulcan from a planet so violent it almost destroyed itself to a home of peace and learning. Of course Vulcans aren't going to mess with what works!

That has been my rant about logic for today. I highly recommend @dduane 's book Spock's World for a much deeper dive into logic and the path Vulcan took to get there.

137 notes

·

View notes

Text

(Disclaimer incase some of y’all don’t have the “Honkai spoilers” and “Genshin spoilers” tags blocked: This post will contain some pretty major spoilers from both games. Also this post is more of a repeat shower thought of mine than a proper analysis)

Something I find… disappointing about Mihoyo’s writing is that it only ever seems to be people who are already in positions of power and authority who get redemption arcs, where as characters who were genuinely just forced into these terrible situations will get villainized and killed off.

Examples:

Ei, leader of a nation and a god, hunted down poor and middle class vision holders (technically a minority group) and stripped them of their will or killed them if they resisted, but the story goes out of its way to show us her grief and hardships, which are supposed to make her worthy of redemption

Dr. MEI, main leader of her era, committed way too many war crimes to list here (main one being experimenting on soldiers and sending them to their death without their consent) and defunded or distracted at least two of the leading scientists working on alternatives, but the story frames her actions as noble and a necessary sacrifice

Otto, part of a ruling lineage and leader of a government party, also committed too many war crimes to list here but we’re gonna focus on the part where he kidnapped and tortured children for science, was given a story the centered around showing us his humanity, motivations, and good intentions/ outcomes

Sirin/HoV one of said children Otto kidnapped and tortured, lashes out and attacks the ones responsible for her pain and those who defend them. Killed off

Kevin, literally just some guy pulled off the street who stepped up when nobody else would, took on a task that was way too big for him to handle, watched almost all his friends die, watched as he was powerless to stop the world from being destroyed, and went along with a desperate and incredibly dangerous plan that he hated, but thought was the only way to prevent what he already lived through from happening again. Deemed a monster that has to be killed

La Signora, a young village woman who’s lover died in a pointless war between gods, had her home destroyed, turned her body into liquid fire, and joined the side that was looking to take down the people who caused her all this pain. Presumably killed off probably not gonna stay that way though so we can come back to this one in a couple years

Some potential exceptions to this trend/ less straightforward examples:

Fu Hua and Kujou Sara (arcs handled similarly, so I’m lumping them together). Though they are both technically leaders, they aren’t by any means the one in charge. Their motivations, reasoning, and potential for redemption is established incredibly early on and the story is quick to show us that even though they’re on the bad guy team at first, they have noble intentions. They also spend the majority of their time in the story actually doing the leg work to prove they’re a good guy

Scaramouche. Though he is technically the child of a god, he’s still a parental abuse victim and the story repeatedly puts him in positions of powerlessness and servitude. He also spent the majority of his life living in poverty. Though he hasn’t exactly been redeemed for his war crimes yet, the story is giving him a chance to work for it

The grand sage. Example of a corrupt person in power we actually did get to take down. Though it should be noted that the story frames it as though that power was never rightfully his in the first place

Idk, it’s not enough for me to go and try and accuse Mihoyo of anything, nor am I trying to say that all these stories were handled poorly (and yes, I’m fully aware that a lot of my descriptions were oversimplifications of the canon). It’s just a pattern that I’m side-eying Mihoyo for. A trend that does make me straight up go “hey, Mihoyo, what the fuck-“

Why is every scientist tampering with human biology and evolution depicted as some puppy-kicking lunatic? Why does the story focus so heavily on demonizing their areas of research and acting like those are the problem, not the fact that they’re committing several OSHA violations? I know I’ve ranted about this point before, but I just find it incredibly strange

#honkai impact#genshin impact#honkai spoilers#genshin spoilers#the Kevin nonsense broke me guys#I’m tired of Mihoyo’s bullshit#I wouldn’t be surprised if this trend was the result of censorship#but some of the characters they choose to villainize genuinely hurt#I’m not as well versed on the sirin lore as some of y’all so if I missed something feel free to add on#it’s 2am and I am very tired#so I apologize if I’m not making sense#it’s just something I’ve been thinking about for awhile and I wanted to get it off my chest#man I don’t even blame Kevin for going a little insane. I would too if I lived through that

42 notes

·

View notes

Note

Please tell me about number plates

*gasp* Of course.

The number plates that I know about particularly are the ones in South Australia, although I know a bit about some of the other Australian states as well. But I will keep this to a brief overview of the structural configuration of standard issue SA plates along with a few points I am particularly passionate about.

Standard issue number plates in South Australia currently are black characters on a white background, and are structured with an S at the start and then three numbers and then three letters. When the state started using that structure, (I will get to the old structure in a little bit) the three letters started with an A, but we are now up to ones that start with C as the first of the three letters, and as far as I am aware (from looking at every single number plate I see) we are now up to the letter R as the middle letter. This means that there is a naturally occurring S000CKS plate out there, which I think is very cool, and I hope its owner really really likes socks. Naturally occurring plates are my passion – custom plates are fine, I guess, but the emergent possibilities of words being created by the configurations are what I really love. More on this later.

They started using the current structure of number plate in 2008, but before that number plates had three letters and then three numbers. When they first started using this old alpha-numeric structure in 1966 the letters started with the letter R, and then once they had used up all the Rs they started using the letter S at the start. At the same time as they were issuing these plates, they were issuing plates for bikes and trailers that had the same structure, but started with the letter T. This meant that after they had run out of configurations starting with the letter S they couldn't go onto the letter T for vehicle plates, so instead they went to the letter U, followed by the letter V and the letter W and then the letter X. Somewhere along the line they ran out of T plates for trailers and bikes and so they started using the letter Y for them. I don't know why they never used the letter Z at the start, but they didn't. When they ran out of these alphanumeric configurations is when they switched to the new 7-character structure with the S at the start.

You still see plenty of cars with the old alpha-numeric structure. My car still has one of the old structure. But they get rarer and rarer as old cars are taken off the road, and also as cars are sold and in a lot of cases unregistered by the seller, which means a new number plate is issued for their new owner. This means that if you saw a car with an old alphanumeric number plate that starts with the letter R or the letter S, it would usually be on a very old car, and you could assume that the driver of that car had owned that car for a very long time, or that they had gone to some other lengths to acquire the ability to use an old number plate for their vehicle. In South Australia once a number plate has been surrendered back to the Department of Transport, which happens when a car is unregistered unless you specifically ask to keep the plate number, it is removed from circulation. The only way to get an old number plate would be to find an old car that had that number plate, acquire the number plate (often by just buying the vehicle) and transfer it to your car.

Or at least that was the case until recently, when the Department of Transport decided to release for purchase, on request, what they call R&S series plates, which are any unused alphanumeric plates starting with the letters R or S. To get one all you have to do is go to the ezyplates website and enter in the one that you want, and if it is available you can purchase it outright and use it for whatever vehicle you want to. This means that now you see more and more R&S series plates, especially because it is a way for people to get a semi-custom plate that doesn't look like a custom plate.

In South Australia, custom plates are not the same color as standard issue plates. The original custom number plates were all yellow with green text, and they had to be a six character alpha-numeric combination, but you could have 2 letters and 4 numbers, or 3 letters and 3 numbers, or 4 letters and 2 numbers, or 5 letters and 1 number. Now they come in just about any configuration - you can get up to 7 mixed characters on a whole heap of different colors - but they are very obviously custom plates. With the R&S series plates you can get something that looks like a normal number plate to the average passerby, so you don’t look like a knob with a custom plate, but which can still be personalised to an extent, because you can custom request any available plate that starts with the letters R or S and has three letters and three numbers.

For instance, a good option for me might be SAR444, given that my name is Sara, or possibly SWI222, because I drive a Suzuki Swift, who I affectionately refer to as Swizz or Swizzy. People whose first names start with R or S could get their initials and then their favourite numbers, or, if you were an absolute madlad, you could request the plate SLU755, probably fully expecting someone at the Transport Department to turn down that request, only to have it successfully issued to you. If you or someone you know owns the black VE Commodore with the 5.8L V8 engine that that plate is attached to, please get in touch. You are either my enemy or my hero, and I need to find out which.

I both love and hate the fact that the R&S series plates are available for custom request. It means that there are more configurations out there that are almost naturally occurring - obviously somebody has had to request them, but it isn't like requesting a regular custom number plate. People have to think about these. And that's good! I love that people are thinking about number plates! But on the other hand, it has removed some of the specialness of seeing an alphanumeric plate beginning with R or S in the wild. It used to be that when I saw one I knew that I was seeing something special - a car that had been loved for a long time, or a number plate that somebody had put a lot of work into acquiring. Now it is just another kind of custom plate, albeit one that most people don't notice.

There is one very sneaky trick to it though – newer issues (although this includes when an old plate is damaged and replaced) say South Australia in little letters at the bottom.

A few other brief facts that I don't have time to go into in depth right now:

The letter Q does not appear in standard issue plates – instead, all government plates (which are blue characters on a white background) feature the letter Q. This is ostensibly to honor the queen, but realistically is probably because Qs and Os look confusingly similar. No one has been able to tell me what will happen with regards to this particular convention when the queen dies.

Back when the standard issue was three letters three numbers, all ambulances used the configuration AMB and then the number of the ambulance, but now they just use regular government plates. This means that there are boring old cars out there with plates that have the letters AMB on them, and it infuriates me every time I see one.

In contrast, I will also regularly see number plates have naturally occurred to say BUS or CAR on them, and when they are on a vehicle that is not that (such as a ute that says CAR, or a car that says BUS) I will laugh affectionately and say "no you're not!", as if the vehicle traveling opposite me at 60+kph can hear me.

The Transport Department will occasionally skip some plates, for a variety of reasons, including that they are inappropriate. Sadly, S###ASS plates were not issued.

Heavy vehicle plates used to start with the letters SB and then have two numbers and then two more letters, while heavy vehicle trailers used to start with the letters SY and then two numbers and then two letters, meaning that somewhere out there, there was probably a truck trailer with the number plate SY57EM. But now most of the states in Australia have switched to a new shared interstate registration for heavy vehicles, which is less fun, because it starts with the letter X and then the letter S, V, N or Q, depending on the state of first registration, so there is a lot less opportunity for fun naturally occurring plates.

There are some options for premium non-standard plates that are not custom, for if you want a fancy plate but have no imagination. These include what were formerly the XX or AA plates, which featured a double letter, three numbers and then another letter, but which now have progressed to having any second letter, and what are known as “Euro style” plates, which mimic European plates and therefore supposedly look better on European cars. They start with an S, then two more letters, then 2 numbers, then another letter. A co-worker of mine has the naturally occurring SED44N on her Mercedes coupe, which I think is hilarious.

In the last two weeks I have seen both the custom plate AAAA and AAAHHHH which, frankly, big moods.

#y'all heard about number plates?#there are a lot of oversimplifications in here and there are exceptions to the rules all over the place#also the wikipedia page contains multiple inaccuracies#also also I know that the SLU755 plate is out there because you can go to the repco website#and put in a number plate ostensibly to help you find parts for your car#but I just use it to see if a plate is currently in use#this is also how I know S000CKS is in use#but it does not work for all vehicles and it especially does not work for truck trailers#but I did see a SY51CM on a truck which is what clicked my brain to the possible SY57EM plate.#also it occurred to me the other day that the naturally occurring plate I would most want would be S291CLB#because that is the name of my fashion label that only makes clothes for me and two of my sisters#well I mean it is the 5291 Club but...#also S444ARA and S555ARA would have been fun naturally occurring ones except the idea of putting MY name on my car#rather than HER name on her seems weird to me

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

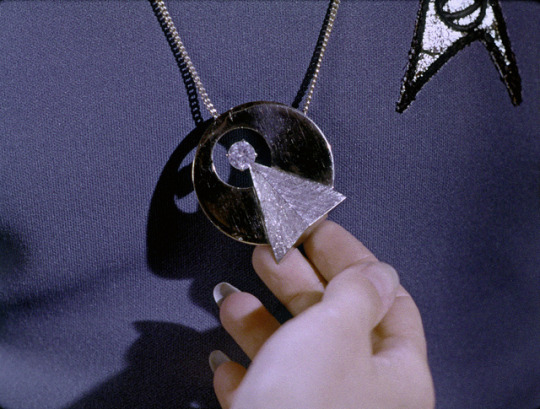

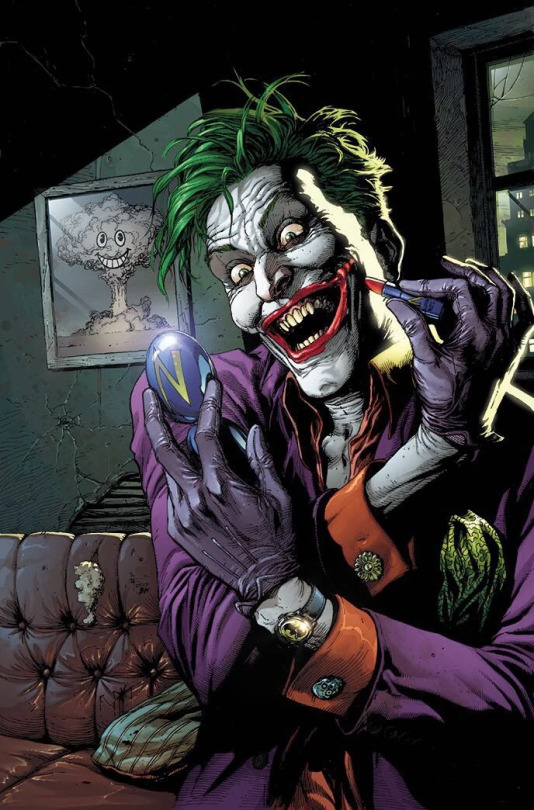

hi i have a brain that can’t shut up and here’s my little pet theory on what i like to call the joker’s trick: the fact that the joker is gay and we all know it, but we cannot ever say it out loud or acknowledge it

this is literally his picture on the wiki btw. also i feel like if you’re here i don’t need to argue that the joker is gay because he literally is. we’re doing gay joker analysis 2.0 here, sir

please note that i’m about to use a bunch of sexist and homophobic language, as i generally find that the most effective way to communicate the cultural norms that i’m about to touch on.

obviously, i’m using the word ‘gay’ when i’m talking about joker as a bit of an oversimplification. i’d use ‘queer’ or maybe even ‘queercoded’ (ugh), because it’s more accurate to how joker is actually portrayed, but when i grew up, gay was still very much a slur and gay-as-a-slur, an f-word, is in fact what the joker needs to be. this is for a reason: to me, the most important aspect about the joker is that he is a creation by straight men, meant to appeal to other straight men.

so yeah, problem solved right? the joker is the symbol for ultimate evil, so he generally represents whatever his writer thinks is the worst thing that exists and for a lot of straight men, that’s a gay dude. kinda sucks, but checks out.

except, that’s not the whole story, because straight men friggin’ love the joker. they’re dressing up as him, they’re quoting him, kinning him, coming up with elaborate backstories for him, leaving really intense youtube comments about how he’s the only one who really gets batman about him. in other words, they think the joker is cool. they think he’s really, really, really cool. They want to be the joker

why? that actually doesn’t check out at all. sure, he’s a villain who does whatever he wants, but most villains do and most of them haven’t been able to capture the hearts and minds of straight men the way the joker has. and joker has gotten more obviously gay over the years as he’s gotten more popular, not less. straight dudes love that the joker is gay!

time for some academic perspectives: our cultural attitude towards gayness are deeply interlinked with our attitudes towards gender roles and masculinity. and masculinity is a deeply strange concept and it is something that a lot of comics concern themselves with (see: straight men appealing to other straight men). while most comic book men are usually examples of hegemonic masculinity (the culturally ideal form of masculinity), the joker is at his core a failure of hegemonic masculinity, and him being gay is the easiest shorthand to straight men for communicating this. a true man is a straight man is a masculine man is a man who is not feminine is a man who is not attracted to men. queercoding men and failing masculinity is usually one and the same in practice.

here’s another thing about manhood: it’s often precarious. with ‘precarious manhood’, we refer to the phenomenon that manhood for men often feels like something that can be taken away from them. while being a woman is often conceptualized as something innate, for men it is much easier to be accused of not being a ‘real’ man. as such, men tend to be more pre-occupied with their own masculinity and often remain in a more anxious state in which they constantly try to re-affirm their manhood to both themselves and their surroundings.* this is what many people incorrectly refer to as toxic masculinity btw. It should also be noted that hegemonic manhood is a cultural ideal and therefore attaining it is fully impossible and this is leaving a lot of men frustrated. they reach for an unattainable goal under the treat of cultural punishment if they fail. also, this effect is generally stronger in straight men, as queer men generally already ‘know’ that they will never reach hegemonic masculinity, as it is defined through being attracted to women only, and therefore, in this aspect, they can walk the mile

so what is a frustrated straight man who is feeling like a failure of masculinity to do? well...what if there was a role model for you who is on every account a failure of masculinity too and he was thriving? what if there was a guy who’s laughing about all these gender rules and breaking them and maybe it made him even more badass? maybe there’s this complete failure of masculinity, not just walking the mile but running directly in the opposite direction and he’s scary and powerful and maybe that’s true power and maybe you are in some way even more powerful (masculine) than all those other guys who are effortlessly performing their masculinity. what then?

but is he gay? don’t worry straight men, of course he isn’t :)

(is he gay? yeah)

(but is he?? no, he isn’t (although he is))

seriously, is the joker gay? yes! but also no! because his purpose is to be a (lol) safe space for straight men to project their anxieties about their own masculinity on. the joker has to be gay in order to be an effective failure of masculinity, but he can’t be gay because then he’s just some gay guy whose nature is just naturally different from straight men/real men and straight men can’t project on him anymore.

so yeah whoops, it’s still homophobia. but at least it’s weird homophobia. it’s what the joker would have wanted

* this also can lead to much greater difficulty for women to go against their assigned gender role, which is often constricting and oppressive. i blog about this a LOT on my main, so please don’t come for me on this

#batman stuff#this asshole#warning: this is very long and i don't like to capitalize#if there's any terms in here that need some more clarification don't hesitate to shoot me a message#i never know which terms are common knowledge and which aren't

292 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wonder Egg Priority Episode 4: Boys’ and Girls’ Suicides Do Mean Different Things (But Not in the Way the Mannequins Want You to Think!)

So, let’s talk about this for a second. After I got over my initial knee-jerk reaction, I realized I wasn’t sure how to make sense of exactly what the mannequins were arguing for here. So let me rephrase their statements to make the argumentative structure more explicit: Because men are goal-oriented and women are not, because women are emotion-oriented and men are not, and because women are impulsive and easily influenced by others’ voices and men are not, boys’ and girls’ suicides mean different things – girls are more easily “tempted” by death, and therefore, more likely to require saving when they inevitably regret their suicide. While Wonder Egg Priority, so far, seems to agree with the vague version of the mannequins’ conclusion, namely that boys’ and girl’s suicides mean different things, it refutes the gender-essentialist logic through which that conclusion was derived.

The mannequins choose a decidedly gender essentialist approach in explaining the difference between girls’ and boy’s suicides; they argue that the suicides are different because of some immutable characteristic of their mental hard wiring (in this case, impulsivity, emotionality, and influenceability). Obviously, this is a load of bull, and Wonder Egg Priority knows it. The mannequins are not exactly characters we’re supposed to trust, seeing that they’re running a business that is literally based on letting these kids put themselves in mortal danger. As faceless adult men, they parrot and possibly represent the systems that force these girls to continue to be subjected to physical and emotional trauma (it’s probably more complicated than this, but four episodes in, it’s hard to say more). So, we’re probably supposed to take what they say with great skepticism. Also, the director, Shin Wakabayashi, has recently said that in response to these lines, Neiru was originally going to object, “When it comes to their brains, boys and girls are also the same,” (which unfortunately is not exactly true and is somewhat of an oversimplification, but the sentiment is there). While that line ultimately did not make it in, Neiru does reply with a confused and somewhat indignant, “What?!”, a reaction that gets the message across. Neiru is not a fan of gender essentialism, and as a (more) sympathetic character, we’re supposed to agree with her.

That is, the differences between boys and girls is not something inherent to their biology or character, but something constructed by culture and experience. This rejection of gender-essentialism is apparent in Wonder Egg Priority’s narrative, which takes a more sociocultural perspective on the difference between boys’ and girls’ suicides. It says, well of course boys’ and and girl’s suicides don’t mean the same thing, that’s the whole reason why we’re delving into the experiences specific to being a girl (cis or trans) or AFAB in this world – to show you how girls’ suicides are influenced by systems of oppression perpetuated by those in power (ie. the adult, in this specific anime).

And all the suicides we’ve seen up until now tie into that somehow. For instance, Koito is bullied by her female classmates who think that Sawaki is giving her special treatment. This is a narrative that comes up over and over again, in real life as well: that if a young girl is being given attention from an older man, then it’s her fault – that she must want it, or at least enjoy it somehow, and that it signifies a virtue (eg. maturity or beauty) on her part. And if Koito is actually being given such treatment by Sawaki, an adult man in a position of power over her, that is incredibly predatory.

And we all know that child sexual abuse is something that overwhelmingly affects girls, with one out of nine experiencing it before the age of 18, as opposed to one out of 53 boys (Finkelhor et al., 2014). Regardless of whether Sawaki was actually abusing Koito or if the students only thought that he was, Koito’s trauma is ultimately the result of this romanticized “love between a young girl and adult man, but not because the man is predatory, but because the girl has some enviable virtue that makes her desirable” narrative. Similarly, in episode 2, Minami’s suicide is driven by ideas related to discipline and body image in sports, which while not necessarily specific to female and AFAB athletes, is framed in an AFAB-specific way. For instance, take the pressure on Minami to “maintain her figure”. Certainly, male athletes also face a similar pressure, but we know that AFAB and (cis and trans) female bodies are subject to closer scrutiny and criticism. We know that young girls are more likely to suffer from eating disorders. And Wonder Egg Priority situates Minami’s experience as decidedly “about” AFAB experience when her coach accuses her change of

figure due to her period as a character failing on her part.

Likewise, episode 3 delves into suicides related to “stan” culture, this fervent dedication to celebrities that is overwhelmingly associated to teenage girls. And Miwa’s story, in episode 4, explicitly shows how society responds to sexual assault. When Miwa does have the courage to speak up about her assault, she’s instantly reprimanded by basically everyone around her. Her father is fired because her abuser was an executive of his company. Her mother asks her why she couldn’t just bear with it, telling her that her abuser chose her because she was cute, as if that’s supposed to make her feel better about it. Wonder Egg Priority shows that this sort of abuse is a systemic problem, a set of rules and norms deeply engrained in a society and upheld by all adults, regardless of gender, social status, or closeness (to the victim). Wonder Egg Priority says that, yes, girls’ and boys’ suicides have different meanings, but it’s not due to some inherent difference between the two, but the hostile environment in which these girls grow up. Girls are not more easily “tempted” by death, they just have more societal bullshit to deal with.

But Wonder Egg Priority goes further than just showcasing how girls’ (and AFAB) experiences are shaped by sociocultural factors. The story also disproves the supposedly dichotomous characteristics that the mannequins use to differentiate girls and boys (i.e. influenceability/independence, impulsivity/deliberation, emotion-orientation/goal-orientation). If the mannequins are indeed correct, and that girls are just influenceable, impulsive, and emotional, you’d expect the girls in the story to be to be like such too. Except, they aren’t. Rather, they’re a mix of both/all characteristics. This show says that, certainly, girls can be suggestible, but they’re also capable of thinking for themselves. For instance, when Momoe asserts her own identity as a girl at the end of episode four, she rejects the words of those around her who insisted that she isn’t a girl. If she were as suggestible as the mannequins believe her to be, that would never have happened – she would have just continued believing that she wasn’t girl “enough”. But, she doesn’t because she is equally capable of making her own judgements. Likewise, Wonder Egg Priority shows that girls can be impulsive, but they can also be deliberate and pre-mediating. When Miwa tricks her Wonder Killer into groping her to create an opening for Momoe to defeat it, she’s not doing it out of impulse – it’s a pre-mediated and deliberate choice unto a goal. And Wonder Egg Priority continues, girls can be equally emotion oriented and goal oriented. Sure, the main girls are fighting because they have the goal of bringing their loved ones back to life, but those goals are motivated by a large range of emotions, from guilt to anger, grief, compassion, and love.

Being emotion-driven doesn’t mean you’re not goal-driven, and vice versa. In fact, in this case, being emotional drives these girls toward their goals. In other words, none of these traits that the mannequins listed are either “girl traits” or “boy traits”. Being one does not mean you can’t be the other, even if they seem dichotomous at first. Wonder Egg Priority’s diverse cast of multi-dimensional female characters allows it to undermine the mannequins’ conceptualization of gendered roles, refuting the idea that these (or any) character traits should be consider gendered at all.

As an underdeveloped side thought, I think Wonder Egg Priority’s blurring of gendered roles is also well-reflected in its style. There’s been a lot of talk about whether Wonder Egg Priority constitutes a magical girl series, and I think that’s an interesting question deserving of its own essay. Certainly, it does follow the basic formula of the magical girl story: a teenage heroine ensemble wielding magical weapons saves the day. But it also throws out a lot of the conventions you’d expect of a magical girl story – both aesthetically and narratively. Aesthetically, it’s probably missing the component that most would consider the thing that makes an anime a magical girl anime: the full body transformation sequence, complete with the sparkles and the costume and all that. Narratively, the girls are also not really magical girl protagonist material – they’ve got a fair share of flaws, have done some pretty awful things (looking at Kawai in particular; I still love you though), and aren’t exactly the endlessly self-sacrificing heroines you’d expect from a typical magical girl story. On the other hand, the anime also borrows a lot from shonen battle anime. We get these dynamic, well choreographed action sequences full of horror and gore, the focus on the importance of camaraderie between allies (or “nakama”, as shonen anime would call it) exemplified through all the bonding between the main girls during their downtime, and in the necessary co-operation to bring down the Wonder Killers. That said, this anime is not a shonen; the characters, types of conflicts, and themes are quite different from those that you’d find in a typical shonen. The bleeding together of the shonen genre and the magical girl genre, at the very least (and I say this because I think it does way more than just that), reflects Wonder Egg Priority’s interest in rebelling against conventional narratives about girlhood and gender.

#wonder egg priority#wonder egg priority analysis#wep#w.writing#my writing#anime analysis#analysis#anime#w.analysis

528 notes

·

View notes

Note

I love you're writing skills! How would be the reader react when she travel the time back so like the 1600 in England?. And England would she see her in modern clothes. She want go back to her time(2020). Im so sorry for my bad English

Thank you, that is very sweet of you. Also don’t worry – your English probably isn’t as bad as you think.

If you want to see anything else set in that period, go and check that Pirate AU! Post. Now on to this here.

Yandere England – 1600s/Timetravler

Whether you would like it or not, you would find yourself hurtling through time and landing in England during the 17th century. Right in Puritan England to be precise, literally the worst decade to land into right after ending up in the middle of a battle. You would be wandering the countryside, in total confusion as well as in complete panic. That would be how Arthur would find you. He would be heading back home, utterly disgruntled by the state of affairs that he would have to suffer under. Then he would notice you, an alien entity by all means, in your strange clothing and foreign manners. First, he would consider just leaving you to your fate (which could be very gruesome) as the loon you would appear to be to him. Then he would remember the supposed Christian values of hospitality and altruism and approach you to take you home with him.

You would be both relieved and frightened to see somebody approach you. Through his clothing it would dawn upon you that you were really in the past. Despite fearing being deemed a witch or being interrogated or suffering from any other fate that would cross your mind, you would know that you would need help. The moment Arthur would open his mouth to inquire about you, the final nail would be hammered in the coffin. The Old English that would meet your ears would be absolute proof that was once history would be your present. A notion that would be affirmed when Arthur’s face would wrinkle in confusion when you would use your English.

Your strange use of his language would confuse, but would nevertheless ring a bell in the back of his mind. It would remind him how English had developed over the centuries. Would your way of using it just be a natural result of further evolution, hence making you a … timetravler? That would be at least what you would be trying to convey over the language barrier. Arthur would be sceptical at first, wanting to rule out all other possibilities before believe you. If you’d think him to be a fool, then you’d have something else coming. Then you’d try to use evidence to convince him.

Quickly, he grabbed the strange thing you were holding out to him. After giving you a brief mistrusting look, he would take a few steps away from you. A paranoid bastard as ever, he turned to stand in such a way that you couldn’t see everything he was doing while keeping an eye on you.

The thing that you handed to him was unlike anything he had ever seen before. It was rectangular and slim, smooth with its dark glass and opaque surfaces. He glimpsed his own cruel visage in the reflection. Was it nothing more than a strange mirror?

Then he went on to inspect the sides, the tips of his fingers finding a few elevations in the material. Curious, he pressed one of them …

… and nearly dropped it when the dark glass promptly lit up and it emitted a strange sound. You yelled besides him, suddenly directly at his side since your device had been endangered. He was sure that hadn’t his reflexes been so quick, then he would have to defend himself against a very enraged stranger. Instead, you glare at him, as irritated as you were, and tried to snatch your thing back.

Agitated by your action in turned, Arthur roughly pushed you away, sending you sprawling to the ground. You cussed at him, the aggressor recognising a few of the swears you tossed at him but not finding himself bothered enough to respond and instead staring at the picture that had manifested.

There was a colourful background, the nuances and lines and shadows showing a painting that was far more realistic then any he had ever seen before. In front of it, a series of number shined at him. One set was probably the time, he deduced, while the other was most likely the date from how it was written.

2021 …

That was nearly 400 hundred years in the future. He looked at you, observed how you had picking stones out of your scraped and bleeding palms.

Despite your disagreeable demeanour, you would likely prove very useful to him.

He would promptly take you with him, trying his best to convey to you through gestures and miss-matched words that he would only want to help you. If you prove define, then he would coerce you into following him by taking your smartphone hostage. Once you would calm down, then you would rationalize that this would probably be the best option you could receive and concede his wishes.

Arthur would keep you in his house, ensure that all the servants would steer clear from the rooms he would house you in, and gradually butter up to you, with all intentions of drawing the details of his future out of you. Other than that, he would intently observe you, knowing that the behavioural patter say a lot about a person, and in extension, give clues about the environment they grew up in. And needly to say, he would be very surprised by some things.

“You know, it is the third time you demand to be allowed to wash yourself this week. Don’t you think you are going too far? There is miasma in the water, and if you continue like this, not only will you render yourself a fool, but you’ll also become sick”, he chided you as he watched you hauled a bucket up the stairs.

As weak as you were, you were struggling with your heavy load, evidence to the lack of physical labour you had done in your life. It made Arthur ask himself if everybody in the future would be as weak and spoiled as you are, or if you were just the exception.

Either way, while manners and etiquette called for him to ease your burden which you evidently couldn’t manage on your own, he found the sight of you straggling up the flight of cold stone steps far too amusing to intervene.

With trembling arms, your set down the bucket and stared at him, eyes shooting daggers up at him. “In case you didn’t know, it is dirt that actually makes people sick. It is cleanliness that prevents infection. Which is why you would do well to wash daily as well!”

With a frown, Arthur picked up his shirt to sniff it. In his opinion, he didn’t stink, so he didn’t see what you were making such a fuss about. He was also sure he had understood you correctly – the two of you had managed to sort out things to the extent that you could communicate fairly well.

“I think that changing underclothing daily and bathing once a month to be sufficient. And now, before you say anything, be sure to keep your attitude in check. I’ve had more than enough of it”, he told you.

He watched your face wrinkle and swore he heard you mutter: “Damn patriarchy and its superiority complex.”

He didn’t know whether to be alarmed about your very simplistic, black-and-white view of the world and your grievous oversimplifications of the current era or be amused about how you thought you knew everything. Either way, he would have to take your words about the future with a grain of salt – who knew just how skewed your recounts would be.

“I fail to see how this has to do with that. The matter at hand is about the guest treating the host with respect, expected courtesy allowing humans to live together. I could put you out on the streets if you keep being a brat”, he countered.

You grasped the handle once more, water spilling over the rim as you picked it up with both hands. “We both know that you wouldn’t do that. You value me too much.”

And oh, in what ways he was beginning to value you.

For one, he would detest how condescending you would be, due to having all the knowledge of the next centuries and all the benefits that would come with it. Yet, he would bare most of it. When he wouldn’t, he’d let his sharp-tongue and centuries worth of life experience come to light. He would mock you for your nativity and prod at you for being coddled and accustomed to yet-to-be luxuries.

Arthur would tell you that he would put effort in finding a way to send you back to your own time. That would be a shameless lie. He wouldn’t be interested in anything of the sort. Rather he would insist on you staying with him, to help him further his imperial ambitions. Besides, you would be the most interesting and riveting thing that would have happened to him in ages. He would quickly grow attached to you, and with you having nobody else than him (he would ensure that) in a harsh and foreign world of which you would truly know little, you would find yourself relying on him.

He might tell you that he is a personification. Secrets for secrets, after all. And with him providing proof of his semi-immortality and the absurdity of time travel having happened you would be inclined to believe him. England would also tell you that if you would return to your own time, he would be sure to seek you out, so that you can be back together again. Besides rising alarm bells in your head, you would find yourself asking just how much of the timeline you would end up altering with the scrapes of information that he would wheedle out of you.

155 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Miss Americana" Director Lana Wilson on Capturing Taylor Swift, Mid-Transformation

By: Chris Willman for Variety

Date: January 31st 2020

Lana Wilson was taking a risk - albeit a pretty good bet - when she set out to make what turned out to be “Miss Americana,” her new Netflix documentary. As Taylor Swift told Variety:

“When I began thinking about maybe possibly having a documentary-type thing happen, it was really just because I felt like I would want to have footage of what was happening in my life, just to have later on in my life, even if we never put it out, or even if we put it out decades down the line. When we brought Lana on board, I was pretty open with her about the fact that this may be something that I wasn’t actually ready to put out. So I think we began the process without a lot of pressure, because I didn’t necessarily think that it was an actual eventuality to put out the documentary.”

Wilson was too fascinated by what she was getting early on to worry much about whether her subject would sign off on releasing it. At the outset, she was catching Swift at the end of the “Reputation” album/tour cycle, when Swift was finding a more contented place in her personal life and finally exorcising Kanye-gate from her system. The star quickly moved on to the making of “Lover,” her most upbeat album, with Wilson getting fly-on-wall footage that captures the joy of creation and eureka moments in the writing process in a way few films ever have. And then things got more interesting altogether when Swift decided that the days she could afford to be standoffish about what was happening in the country had come to an end. The movie - and by now, it was a movie - had its third act.

Variety spoke with Wilson for the magazine’s cover story last week on Swift, prior to “Miss Americana’s” Sundance premiere. Here’s a breakout of more of that conversation.

There is some footage in the movie that goes back a few years that clearly predates your involvement. When did you start filming - was it during the “Lover” writing and recording sessions or the “Reputation” tour before that?

I came on during the tour. She had been collecting bits and pieces of footage; she often filmed stuff with her own cell phone - songwriting stuff. Netflix introduced us, and we really hit it off the first time we met. She had watched my previous work, and I had admired her for years, not just for her music, but also the fact that she had written all of her own songs since she was 15, and that she’s the sole creative force behind the whole shape of her career. When we met, I remember being excited that she didn’t want to make a traditional pop star documentary. She knew that she was in the middle of a really important time in her life, coming out of a very dark period, and wanted me to collaborate on something that captured what she was going through that was raw and honest and emotionally intimate.

When we first talked about it, she immediately wanted me to bring my perspective as a director to what was going on with her now and to make a film that really had something to say. I think the first time we met, we talked for 20 minutes about narrative structure in documentaries, and we even talked about film score in documentaries. At one point she said that she didn’t like documentaries that are like propaganda, and I was thrilled to hear that. In my work, I take stories that are often told through sound bites and headlines and bring depth and complexity to them. My goal is always to reveal the humanity that’s beneath the oversimplification. And to me, there are few things more frequently diminished and reduced by others than female creative forces.

It could be seen as a feminist statement, or at least some kind of intention on her part, that she picked someone who’d made an abortion documentary (“After Tiller”). It could also mean that she was just more comfortable with a woman.

I think that’s totally true. When I started filming, it was before she’d come out politically. But that said, even before meeting her, I could only imagine how much pressure and scrutiny she’d faced as a powerful and successful female artist. And I definitely sensed that those pressures would be ones that other people and especially other women and girls could relate to. Obviously, yeah, I’m a female artist working in a male-dominated industry. So although Taylor and I inhabit very different worlds, I figured that we’d have some shared experiences. And I also worked with an all-female crew, which I do think helped her feel comfortable right off the bat, and a small crew. When I met her, she hadn’t done an interview in almost three years. The first one she did was an audio (-only) interview with me for this film. So it was a big deal, and trust was a big part of that.

You had an all-female crew, but Morgan Neville’s name is on there as a producer, and he’s not a gal. [Laughter.] What’s his role in it?

He was a part of the creative process, and it was wonderful to get to work with him, as a creative sounding board, from start to finish. On the crew, I will say that we did always have male production assistants, because I like trying to show people that men can fetch coffee for women, and not just the other way around! So that was the only exception to the all-female rule.

It had to have been a small crew, when you were filming the fly-on-the-wall creative stuff in the recording studios, sometimes in very small control rooms.

It was often just me and one or two other people in the room with her, trying to keep the footprint as small as possible. You know, no one had filmed her writing songs before. That was some of my favorite stuff to film, but it was also the stuff where we tried to really be the most low-key presence possible. You’re just in a tiny room, and it feels so amazing to watch her get in the zone creatively. One of the most fun parts for me as a director is when it feels like you’ve been in the studio for enough hours that everyone is so relaxed that you really feel invisible in a wonderful, exciting way.

When she’s having the talk with her team about wanting to make endorsements for the midterm elections, which is maybe the most important scene in the film, it’s not clear if that is something you shot or if that was something that was on the spur of the moment, where she had someone get a camera in your absence.

That was spur of the moment. So that was something someone on her team shot who was pretty good with the camera. That was very last minute. I’d been starting to work with her and talk with her before that, and I’d say, “If something’s happening last-minute that could be at all important or meaningful, film it with your cell phone, of if there’s someone around you that has a little DSLR camera or something, they could film it.” It allowed us to get really powerful, crucial scenes like that one that might’ve been hard logistically to get otherwise. And I love the personal quality of that material from especially the few little bits of stuff from her cell phone.

She told us she wasn’t sure she wanted to actually make or release a movie when filming started. Did she make that clear to you when it started? Like, this might be on spec, and might not come out?

Well, it was less talking about the end result and more, honestly, just talking about what she was going through emotionally at that time and the kind of things that were on her mind. Then we’d brainstorm stuff that could be cool to film. I love the idea of filming really quiet, almost more mundane moments, because I think that ordinary/extraordinary contradiction that’s so central to the life of someone in the public eye is really interesting. I loved that moment early in the film where she’s alone in the car in the dark after the show riding to her hotel room - the idea of going from being on a massive stage in front of tens of thousands of people to being an ordinary person alone just going to bed at the end of the night.

She’s already been pretty candid with her fans. There are moments in the film where she’s shown as being annoyed with the fans and photographers gathered outside her door and that sort of thing. Do you think she felt okay with being portrayed as not being happy at all times?

Oh yeah, totally. She’s a complex human being, and I think whether you like her music or not, if you watch this movie, you really get to know her as a human. And as you say, she writes so candidly in her lyrics about the hardest times, the times when she made mistakes. And that is what her fans love her for. But a lot of people don’t share their hard times. The most popular photos on Instagram are of weddings and babies, when what’s really relatable and what’s meaningful is connecting with someone over that time things weren’t perfect, or the friendship or relationship that didn’t work out, or the argument you had with your mom or something. You know, everyone wants to feel less alone in the more difficult experiences in life. And that’s one reason why they turn to art. And I think it’s why people watch movies. And the happy moments are meaningful when you’ve also been through the sad ones. Young girls need to see that their heroes are just as human as they are. And I think girls and boys of all ages could benefit from that reminder.

I want people to be surprised by it because I think that Taylor Swift is someone who everyone thinks they know. But I think if people start watching this film, they’ll realize they’re watching a film about this iconic artist deciding to live life on her own terms, and it’s a feminist coming of age story. I think they’ll be surprised by her sense of humor and her self-awareness, and they can appreciate the craft of songwriting, for instance. So I hope that even if people are not fans, that they’ll watch the movie and be really surprised and also feel like they’ve just met a complicated, layered human being.

Very few people at the superstar level have the gift of healthy self-awareness that she seems to have. Self-consciousness, yes, but self-awareness, that’s more rare.

Yeah, it’s so true. I’m sure you’ve seen bits of the home movies in some of her videos in the past. When I looked at the home movies, what struck me the most about them is that she really always has been the same person. She’s been kind and generous and smart and imaginative and very hardworking since she was a girl. At age 11 she knew exactly what she wanted to do with her life. One of my favorite moments in the archives in the film is this clip of her, where she’s like in a diner and it’s just after the release of her first album, and she’s 16. Her childhood dream has just come true. And she tells the interviewer that she wakes up everyday being like, “Yes, this is happening.” But then she tells herself, “Now you have to figure out how to make it last.” That is so her. She had so much maturity and pretentiousness then, and she knew she wanted this to be her career and her life, and she wanted to write songs forever. It’s incredible to see a person at that age that self-possessed and cognizant.

At one point she says she wants to use her platform to speak out because she’s aware she won’t be in this position forever, where her opinions have some kind of import. Not that she’s predicting a major downfall, but she knows she won’t always have this attention. That’s undoubtedly true, but at the same time, she’s one of the only ones besides Beyonce that we would imagine being almost as big a star in 20 years, and not necessarily subject to the normal standards of diminishment of interest.

She’s conscious of the historically short lifespan of female pop stars, and it’s so poignant when she says that. But it’s hard to know what will happen, though, because she issuch a trailblazer. I mean, there’s just been no one like her, and her fan base and the relationship she has with her fans is so unique, and, I mean, she’s already done so many things that no one else has done before — who knows what will happen in the future? She is cognizant of what’s happened in the past and what’s going to happen in the future … but it could be anything, because she’s different than anyone that’s come before.

We can hope we all live long enough to find out what a 50- or 60-year-old Taylor Swift is like.

I love that idea too. I want to go to the arena tour of a 60-year-old Taylor Swift. I want to know what the songs she’s writing then are.

The last third of the film focuses on her decision to make a political statement and what comes after.

It was a profound decision for her to make, and a multilayered one. In that, I saw this feminist coming-of-age story that I personally connected with, and that I really think women and girls around the world will see themselves in.

You didn’t actually have the “Miss Americana & the Heartbreak Prince” song in the movie, but that’s the song on the album that most speaks to her political turn. So it seemed like a good thing to title the movie after?

It was cool because it’s obviously, yeah, a reference to this song she wrote that has political themes. It was interesting that when the documentary was announced, her fans instantly understood some of the themes the film would have, because of the song title. And then for me, even if you don’t know the song, I see the movie as in some ways looking at the flip side of being America’s sweetheart. So I like how the title evokes that, too.

You have the twin moments of disappointment in the movie. Early on, you have the Grammy disappointment, and then later there’s the midterm result disappointment. Those are the parallel scenes, almost, where she’s having to deal with the results not turning out as she planned and one of these ultimately being more important than the other.

I’m glad you noticed that. That means a lot. One thing that I think is amazing about her is that she goes to the studio and to songwriting as a place to process what she’s going through. I loved how, when she got the Grammys news, this isn’t someone who’s going to feel sorry for herself or say “That wasn’t right.” She’s like, “Okay, I’m going to work even harder.” And I think it’s amazing how you see her strength of character in that moment when she gets that news. Then with the election results, I loved how she channeled so many of her thoughts and feelings into this song (“Only the Young”). It was a great way to kind of show how stuff that happens in her life goes directly into the songs. You get to actually witness that in both cases.

Were you surprised that she addressed having had what could be described as an eating disorder? She seems hesitant to use that term but finally does. She’s been open about so many things, but that’s not something that she’s revealed.

No, that’s one of my favorite sequences of the film. I was surprised, of course. But when you hear her talk about it, I love how she’s kind of thinking out loud. And yeah, she’s an icon of beauty, but even for an icon of beauty, as she articulates so beautifully, women are in this double bind situation. It’s impossible for anyone to meet every standard of beauty. It’s an impossible situation. And every woman will see herself in that sequence. I just have no doubt. And I do think people will be really surprised by it.

I tend to be clueless about these minor shifts in weight or body size, until people point them out en masse. It never would have occurred to me that she was any less thin on the “Reputation” tour until I started seeing comments about weight gain. But there are those who have their antennae out for the slightest change, and often it’s women, maybe it’s because you’re under that scrutiny yourselves.

But you can also just not notice people being really skinny, because we’re all so accustomed to seeing women on magazine covers who are unhealthy skinny, and that’s become normalized. I think it’s interesting what you say about what you read during “Reputation” about her weight, because you really can’t win. There is a moment in the film where you see that part of the media backlash she experienced during 2016 was people saying, “Oh, she’s too skinny.” People complain if you’re too skinny, and if you’re not too skinny, you’re too fat. It’s incessant, and I can say this as a woman: It’s amazing to me how people are constantly like “You look skinny” or “You’ve gained weight.” People you barely know say this to you. And it feels awful, and you can’t win. So I think it’s really powerful to see someone who is a role model for so many girls and women be really honest about that. It’s a brave thing of her to do, and I think it will have a huge impact.

Her interactions with Kanye West are such an essential part of the story, but that’s not a name that has really ever escaped her lips publicly since 2010; she’ll say “a person” or something euphemistic if she has to address it. So I was in suspense to see whether or how much it would come up in your film, given how little capital she wants to give this guy in her life. It’s a crux, twice, of her journey of self-acceptance, but it’s easy to imagine her not wanting it in the film.

I think it’s an important part of the story, but I wanted to position… Like, with the 2009 VMAs, what was surprising to me when I asked her about it was that she talked about how the whole crowd was booing, and she thought that they were booing her, and how devastating that was. That was something I hadn’t thought about or heard before. And it meant a lot more to me because it made more sense in the context of her being this extraordinary young artist who is doing so well, and who, like so many performing artists, loves applause. And then she is on stage [still as a teenager] and it felt like all these people were booing her. When you put it that way, it’s so much more relatable to me, and it’s understandable to anyone, because we all want people to like us. And being on stage with a giant crowd booing would be horrible for anyone. So we tried to use it in a way that showed it in a slightly different light than people have seen before... We all care about what people think about us. It’s not a celebrity problem. It’s a universal one. It’s something everyone goes through, and I think the difference is that with Taylor, it plays out on a massive international stage.

At the outset, you’ve got her in voiceover talking about how she wanted to be the good girl and be accepted. And in the end, she is a good girl, so maybe that’s not a bad thing to want to be, but there are gradations of that. She’s played around with bad girl archetypes in the “Reputation” imagery and songs, but it was role-playing to a degree. Where do you think she ended up on the scale of all that?

She starts out as a good girl and she ends up as a good girl who’s decided to speak out. You know, we live in a society in which girls are taught that other people’s approval is of paramount importance to our self-worth. “Do they like me? Was I nice enough? Are they mad at me?” Every woman I know is constantly asking herself these questions. So it’s so relatable in that way. But it’s not about not being a good person. I think that the arc in the film and what Taylor went through was letting go a little bit of what other people think of her, deciding to live on her own terms, and to put her own values first. The transformation that you see is going through this period where she lets go a little bit of that. She’s a good girl speaking out now, in a way. You can’t win everyone over. No one can. I think she’s really accepted that in a deep way.

#this is a somewhat lengthy interview but well worth the read...#Lana Wilson#interview#variety#Taylor Swift: Miss Americana#taylor swift#about taylor

203 notes

·

View notes

Text

it’s touch time baby! and by that i mean bucky’s incredibly complicated sense of touch. i will try not to attach lit theory to it. we shall see. good news! it’s present me and i did not attach lit theory to it. under a cut because it is....so long

When it comes to Bucky and human contact it’s complicated. Because it can’t be as simple as ‘anyone who touched me hurt me’ - they brainwashed him into total dependence on their ministrations, which means they had to be everything for him. You have to have a sense of what is good or bad - is there a neutral kind of contact? With him I’m not sure. Everything means something. And before I continue, I should note that qualifying anything as good or bad isn't the right scale to use not because it's too simplistic (in fact oversimplification is part of his life but that’s for another day) but because it would be too unfamiliar to use in good faith when talking about him so actually the scale should be punishment to reward when it comes to how he views this sort of thing.

A good way to think about his relationship with human contact is the milk scene in CATWS where Pierce pours the Soldier a frankly strange amount of milk and then never gives any indication of what the Soldier is supposed to do with it. (It doesn’t matter what the intention behind this scene is by the way - the author is firmly dead). This offer of milk is a taunt in some ways, because Pierce is saying ‘you could be human because I’m giving you something the way I would to an actual person sat across from me’ (we can talk about assigning the Soldier a child role in this scene at a later moment) but even while the Soldier is being offered a drink it’s a very clear indication of where the human/Asset line is drawn because he isn’t given an order to drink, and also importantly, he does not take the glass of his own initiative, no matter how sad he may look at the time.

So with that, we can talk about Bucky initiating contact. What we would consider positive physical contact - hugs, comfortable closeness, etc - is not something he is able to initiate. It’s been trained out of it. He can only ask for necessities, and that is not on the list. This has to be relearned.

He can obviously initiate negative physical contact. That’s what he’s meant for. But even that has limits. He is allowed to harm targets and whoever he needs to in order to complete his mission. But outside of that? They can’t have him lashing out at scientists or trainers or handlers, so this sort of thing would have to be severely punished. It’s something of a fine line to walk - you have to train out a violent reaction to unwanted touch in some situations but not in others. And they never truly succeeded, given that he killed people working with him the entire time he was with HYDRA. But in their attempts to train him, how would they go about it? You assign authority to everyone around him. There is one directive to be given: do not harm those with authority over you unless commanded by someone who outranks them. Problem solved. This is why, even when he’s regained memories and personhood, it’s very dangerous if he determines that someone has authority over him or if someone works to get that determination from him.

We’ve established these two ways that Bucky can/cannot initiate contact of his own, so what about reception of this contact? This is where the punishment-reward dichotomy comes in.

Punishment is whatever you can imagine. The lack of peaceful contact, active torture, all sorts of pain. There is always a reason given for punishment, but pain is also a fact of the Soldier’s life, and this distinction is important to retain even while pushing his limits for testing or when he makes a mistake. (He’s human after all, even if everyone pretends like he’s not.) He’s also trained not to flinch. This will be important later.

For a reward - he was clearly treated as not human while everyone around him was pretty aware that he was actually human. And therefore as a human, there is something about skin contact with other humans that is very important. There’s power there, obviously, especially when you’re depriving someone of it. So you give those who are to be trusted a set of rules. Rest a hand on his shoulder as you tell him he’s going out to do good work. He may not understand what good work is, but he’ll associate it with contact, and if you are ever punishing him, you cannot touch him so he knows that it can be taken away. He’s not supposed to want, but it’s a subconscious one that is beneficial to the program. They don’t need to burn it out completely. And obviously if there is a touch to be avoided, there must be a touch on the opposite side of things.

So what does this mean for post captivity?

It means that at some point he realizes that actually, he can make the rules around here. It doesn’t come easily, of course, and probably not all at once.

First, if someone grabs him - anyone - he is allowed to kill or maim them. In fact he should, since he does not want to go back. If their intention is or seems violent, they are in for a bad time. Sometimes it’s panic, but a lot of times it’s with a (relatively) fully functioning mind that he reacts. Bucky can recognize contact that he associates actively with being punishment and now can respond to that.

Anything else is a much grayer zone. He has to relearn how to express discomfort verbally or even physically. He can’t flinch, and he’s probably never going to actively try to bring that back. But what he can learn to do is walk away, or at the very least lean away. Because his current response to something that doesn’t say punishment to him is to just stay there and be uncomfortable. This is difficult, obviously as there are people who legitimately have nothing but good intentions towards him but still can cause discomfort because they do something that he doesn’t actively want or expect. There’s no way to get through that except to give it time and to check in with him. Asking him involves a choice he has to make, but ultimately sometimes that particular discomfort is better than feeling like he’s going to crawl out of his skin just because sitting shoulder to shoulder isn’t something he can deal with at the moment.

And then there’s him actually initiating positive contact. This is also going to take a lot of time. It may even take explanation, and it’s pretty likely that explicit permission would be greatly appreciated.

I know this is very long. It’s something of a complex subject and is probably something I’ll continue to talk about because it’s...kind of a big thing.

#such shadow and carnage and unknown horrors | bucky headcanons#long post#just in case lmao#it's approximately 1100 words i just checked. so buckle up ig

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Could you please explain in more detail what each of the math post-APs are and how easy/hard they are and how much work? Thanks!!

Response from Al:

This can be added on to, but I can describe how Multivariable Calculus is. First off, I want to say not anyone’s opinion should affect how difficult or easy a class would be for YOU. Ultimately, do the classes you’re interested in. Personally, I thought Calculus was cool as subject, so that’s why I pursued Multi. Multi. builds off of BC Calculus, Geometry, and even some of the linear algebra you learned from middle school (not to be confused with the Linear Algebra you can take at TJ), so as long as you have a good foundation in those subjects, I’m sure you’ll do well in Multi. Depending on your teacher, assessments may or may not be more challenging, and that’s why I strongly emphasize take the class only if you’re genuinely into it. Don’t take it because of peer pressure / because you want to stand out in colleges. I’ll let anyone add below.

Response from Flitwick:

Disclaimer: I feel like I’m not the most unbiased perspective on the difficulty of these math classes, and I have my own mathematical strong/weak points that will bleed into these descriptions. Take all of this with a grain of salt, and go to the curriculum fair for the classes you’re interested in! I’ve tried to make this not just what’s in the catalog/what you’ll hear at the curriculum fair, so hopefully, you can get a more complete view of what you’re in for.

Here’s my complete review of the post-AP math classes, and my experience while in the class/what I’ve heard from others who have taken the class. I’m not attaching a numerical scale for you to definitively rank these according to difficulty because that would be a drastic oversimplification of what the class is.

Multi: Your experience will vary based on the teacher, but you’ll experience the most natural continuation of calculus no matter who you get. In general, the material is mostly standardized (and you can find it online), but Osborne will do a bit more of a rigorous treatment and will present concepts in an order that “tells a more complete story,” so to speak.

The class feels a decent amount like BC at first, but the difficulty ramps up over time and you might have an even rougher time if you haven’t had a physics course yet when it comes to understanding some of the later parts of the course (vector fields and flux and all).

I’d say some of the things you learn can be seen as more procedural, i.e. you’ll get lots of problems in the style of “find/compute blah,” and it’s really easy to just memorize steps for specific kinds of problems. However, I would highly recommend that you don’t fall into this sort of mindset and understand what you’re doing, why you’re doing it, and how that’ll yield what you want to compute, etc.