#there was never wei wu shu or jin

Photo

Jonathan Chang and Nien-Jen Wu in Yi Yi (Edward Yang, 2000)

Cast: Nien-Jen Wu, Issei Ogata, Elaine Jin, Kelly Lee, Jonathan Chang, Hsi-Sheng Chen, Su-Yun Ko, Chuan-Chen Tao, Shu-shen Hsiao, Pang Chang Yu. Screenplay: Edward Yang. Cinematography: Wei-Han Yang. Production design: Peng. Film editing: Po-Wen Chen. Music: Kai-Li Peng.

In his Criterion Collection essay on Yi Yi, Kent Jones does something that I endorse completely: He compares writer-director Edward Yang's film to the work of George Eliot. As I was watching Yi Yi, I kept thinking that it gave me the same satisfaction that a good novel does: that of participating in the lives of people I would never know otherwise. George Eliot's aesthetic was based on the premise that art serves to enlarge human sympathy. It's an idea echoed in the film by a character who quotes his grandfather saying that since the introduction of motion pictures, we now live three times longer than we did before -- we experience that many more things The remark in context is ironic, given that the character, a teenager (Pang Chang Yu) who will later commit a murder, mentions killing as one of the experiences now vicariously afforded to us by movies. But the general import of the observation stands: Yi Yi gives us the sweep of life, beginning with a wedding and ending with a funeral, and taking in along the way birth, found and lost love, and other experiences of the Jian family and acquaintances in Taiwan. The central character, N.J. (Nien-Jen Wu), is a businessman caught up in the machinations of his company while trying to deal with family problems: His mother-in-law suffers a stroke and lies comatose; his brother-in-law's wedding to a pregnant bride is interrupted by a furious ex-girlfriend; his wife has an emotional breakdown and leaves for a Buddhist retreat in the mountains; his daughter, Ting-Ting (Kelly Lee), is in the throes of adolescent self-consciousness and blames herself because her grandmother suffered a stroke while taking out the garbage Ting-Ting had been told to take care of; his small son, Yang-Yang (Jonathan Chang), refuses to join the family in taking turns talking to his comatose grandmother, and he keeps getting in trouble at school. And these matters are complicated by the reappearance of N.J.'s old girlfriend, Sherry (Sun-Yun Ko), now married to a Chicago businessman, who joins N.J. in Tokyo on a business trip that puts him at odds with his company. The separate experiences of N.J., Ting-Ting, and Yang-Yang overlap and sometimes ironically counterpoint one another, and the film is laced together by recurring images and themes. Although it's three hours long, Yi Yi never seems slack. A lesser director would have cut some of the sequences not essential to the narrative, such as the performances of Beethoven's "Moonlight" Sonata and the Cello Sonata No. 1, or the long pan across the lighted office windows in nighttime Taipei, but these give an essential emotional lift to a film that has rightly been called a masterwork.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Top Drama China Historical yang akan Datang

serial drama historical andalan 4 jaringan china yang akan datang.

腾讯 (tencent)

1.梦华录 Meng Hua Lu - A Dream of Splendor - Crystal Liu Yi Fei , Chen Xiao, Jelly Lin

2.玉骨遥 The Longest Promise - Xiao Zhan, Ren MIn, Wang Chu Ran, Han Dong, Alen Fang

3.星汉灿烂 Love Like The Galaxy - Zhao Lusi, Leo Wu, Zeng Li

4.春闺梦里人 Romance of a Twin Flower - Ding Yuxi, Peng XiaoRan

5.重紫 Chong Zhi - Yang Chao Yue, Jeremy Tsui, Zhang Zhi Xi

6.说英雄谁是英雄 Heroes - Joseph Zeng, Yang Chal Yue, Liu Yu Ning, Baron Chen, Meng Zi Yi, Sun Zu Jun

7.雪鹰领主 Lord Eagle - Sheng Ying Hao, Sun Rui, Fei Qin Yuan

8.乐游原 Wonderland of Love - Xu Kai, Jing Tian, Zhao JIa Min, Gao Han, Zheng He Hui Zi, He Feng Tian

9.长相思 Lost You Forever - Yang Zi, Deng Wei, Zhang Wan Yi

10.天行健 Heroes (judul rencana akan diubah biar ga tabrakan) - Qin Jun Jie, Maggie Huang, Liu Yu Ning

11.飞狐外传 - The Young Flying Fox - Qin Jun Jie, Liang Jie, Xing Fei, Peter Ho, Sarah Zhao, Lin Yu Shen, Hei Zi, Yvonne Yung

12.只此江湖梦 - Love and Sword - Gao Wei Guang, Xuan Lu, Jia Nai, Martin Zhang, Yuan Yu Xuan, Ren Hao

爱奇艺 (iqiyi)

1.月歌行 - Song of the Moon - Vin Zhang, Xu Lu

2.云襄传 - The Ingenious One - Chen Xiao, Rachel Momo, Tang Xiao Tian

3.显微镜下的大明 - Great Ming Under Microscope - Zhang Ruoyun, Qi Wei, Wang Yang

4.明月入卿怀 - A Forbidden Marriage - Mao Zi Jun , Zhou Jie Qiong , Zhang Xin ,Li Jiu Lin, Eddy Ko

5.请君 - Welcome - Ren Jia Lun, Li Qin

6.七时吉祥 - Love You Seven Times - Ding Yu Xi, Yang Chao Yue ,Yang Hao Yu, Dong Xuan, Hai Lu

8.倾城亦清欢 - The Emperor's Love - Wallace Chung, Yuan Bing Yan, Jason Gu, Zhang Yue

9.九霄寒夜暖 - Warm Cold Night in the Nine Heavens - Li Yi Tong, Bi Wen Jun, Chen He Yi, He Rui Xian, Ma Yue

10.苍兰诀。 - Eternal Love - Yu Shu Xin, Dylan Wang, Cristy Guo, Xu Hai Qiao

11.花溪记(分销) - Love Is An Accident - Xing Fei, Xu kai Cheng, Wang Yi Nuo

12.花戎。 - Hua Rong - Ju Jing Yi, Guo Jun Chen, Liu Dong Qin, Lu Ting Yu, Ma Yue

优酷 (youku)

1.长月烬明 - Till The End of The Moon - Luo Yunxi, Bai Lu, Chen Du Ling, Deng Wei, Sun Zhen Ni, Wang Yifei

2.星河长明 - Novoland: The Princess From Plateau - Feng Shao Feng, Peng Xiao Ran, Cheng Xiao Meng, Zhu Zheng Ting, Liu Meng Rui, Kim Jin

3.沉香如屑。- Immortal Samsara - Yang Zi, Cheng Yi, Ray Chang, Meng Zi yi, Yang Xizi, Hou Meng yao

4.星落凝成糖 - Love When the Stars Fall - Chen Xing Xu, Landy Li, Luke CHen, He Xuan Lin

5.郎君不如意。- Go Princess Go 2 - Wu Xuan yi, Chen Zhe Yuan, LQ Wang

6.隐娘 - The Assassin - Qin Lan, Zheng Ye Cheng, Hu Lian Xin, Du Chun

7.安乐传 - Legend of Anle - Dilraba Dilmurat, Gong Jun, Liu Yu Ning, Xia Nan, Tim Pei, Chen Tao

芒果TV (mango tv)

1.落花时节又逢君 - Love Never Fails - Yuan Bing Yan,Liu Xue Yi, Xu Xiao Nuo, Ao Rui Peng

2.覆流年 - Lost Track of Time - Xing Fei, Zhai Zi Lu, Jin JIa Yu, Cheng Yu Feng, Zhan Jie, Han Ye

catatan: nanti saya update judul resmi inggris dan siapa aktor aktrisnya.

sumber: artikel topik upcoming chinese drama di cerita-silat.net dan Weibo

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

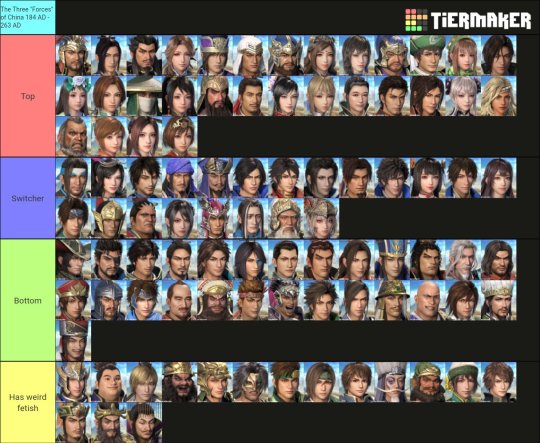

A "historically accurate" and objective allegiance chart of Dynasty Warriors.

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Guide to Taiwanese Name Romanization

Have you ever wondered why there are so many Changs when the surname 常 is not actually that common? Have you ever struggled to figure out what sound “hs” is? Well don’t worry! Today we are going to go over some common practices in transliterating names from Taiwan.

With some recent discussion I’ve seen about writing names from the Shang-Chi movie, I thought this was the perfect time to publishe this post. Please note that this information has been compiled from my observations--I’m sure it’s not completely extensive. And if you see any errors, please let me know!

According to Wikipedia, “the romanized name for most locations, persons and other proper nouns in Taiwan is based on the Wade–Giles derived romanized form, for example Kaohsiung, the Matsu Islands and Chiang Ching-kuo.” Wade-Giles differs from pinyin quite a bit, and to make things even more complicated, transliterated names don’t necessarily follow exact Wade-Giles conventions.

Well, Wikipedia mentioned Kaohsiung, so let’s start with some large cities you already know of!

[1] B → P

台北 Taibei → Taipei

[2] G → K

[3] D → T

In pinyin, we have the “b”, “g”, and “d” set (voiceless, unaspirated) and the “p”, “k”, and “t” set (voiceless, aspirated). But in Wade-Giles, these sets of sounds are distinguished by using a following apostrophe for the aspirated sounds. However, in real life the apostrophe is often not used.

We need some more conventions to understand Kaohsiung.

[4] ong → ung (sometimes)

[5] X → Hs or Sh

高雄 Gaoxiong → Kaohsiung

I wrote “sometimes” for rule #4 because I am pretty sure I have seen instances where it is not followed. This could be due to personal preference, historical reasons, or influence from other romanization styles.

Now some names you are equipped to read:

王心凌 Wang Xinling → Wang Hsin-ling

徐熙娣 Xu Xidi → Shu/Hsu Hsi-ti (I have seen both)

黄鸿升 Huang Hongsheng → Huang Hung-sheng

龙应台 Long Yingtai → Lung Ying-tai

宋芸樺 Song Yunhua → Sung Yun-hua

You might have learned pinyin “x” along with its friends “j” and “q”, so let’s look at them more closely.

[6] J → Ch

[7] Q → Ch

范玮琪 Fan Weiqi → Fan Wei-chi

江美琪 Jiang Meiqi → Chiang Mei-chi

郭静 Guo Jing → Kuo Ching

邓丽君 Deng Lijun → Teng Li-chun

This is similar to the case for the first few conventions, where an apostrophe would distinguish the unaspirated sound (pinyin “j”) from the aspirated sound (pinyin “q”). But in practice these ultimately both end up as “ch”. I have some disappointing news.

[8] Zh → Ch

Once again, the “zh” sound is the unaspirated correspondent of the “ch” sound. That’s right, the pinyin “zh”, “j”, and “q” sounds all end up being written as “ch”. This can lead to some...confusion.

卓文萱 Zhuo Wenxuan → Chuo Wen-hsuan

陈绮贞 Chen Qizhen → Chen Chi-chen

张信哲 Zhang Xinzhe → Chang Shin-che

At least now you finally know where there are so many Changs. Chances are, if you meet a Chang, their surname is actually 张, not 常.

Time for our next set of rules.

[10] C → Ts

[11] Z → Ts

[12] Si → Szu

[13] Ci, Zi → Tzu

Again we have the situation where “c” is aspirated and “z” is unaspirated, so the sounds end up being written the same.

曾沛慈 Zeng Peici → Tseng Pei-tzu

侯佩岑 Hou Peicen → Hou Pei-tsen

周子瑜 Zhou Ziyu → Chou Tzu-yu

黄路梓茵 Huang Lu Ziyin → Huang Lu Tzu-yin

王思平 Wang Siping → Wang Szu-ping

Fortunately this next convention can help clear up some of the confusion from above.

[14] i → ih (zhi, chi, shi)

[15] e → eh (-ie, ye, -ue, yue)

Sometimes an “h” will be added at the end. So this could help distinguish some sounds. Like you have qi → chi vs. zhi → chih. There could be other instances of adding “h”--these are just the ones I was able to identify.

曾之乔 Zeng Zhiqiao → Tseng Chih-chiao

施柏宇 Shi Boyu → Shih Po-yu

谢金燕 Xie Jinyan → Hsieh Jin-yan

叶舒华 Ye Shuhua → Yeh Shu-hua

吕雪凤 Lü Xuefeng → Lü Hsueh-feng

Continuing on, a lot of the conventions below are not as consistently used in my experience, so keep that in mind. Nevertheless, it is useful to be familiar with these conventions when you do encounter them.

[16] R → J (sometimes)

Seeing “j” instead of “r” definitely confused me at first. Sometimes names will still use “r” though, so I guess it is up to one’s personal preferences.

任贤齐 Ren Xianqi → Jen Hsien-chi

任家萱 Ren Jiaxuan → Jen Chia-hsüan

张轩睿 Zhang Xuanrui → Chang Hsuan-jui

[17] e → o (ke, he, ge)

I can see how it would easily lead to confusion between ke-kou, ge-gou, and he-hou, so it’s important to know. I’ve never seen this convention for pinyin syllables like “te” or “se” personally.

柯震东 Ke Zhendong → Ko Chen-tung

葛仲珊 Ge Zhongshan→ Ko Chung-shan

[18] ian → ien

[19] Yan → Yen

I’ve observed that rule 18 seems more common than 19 because I see “yan” used instead of “yen” a fair amount. I’m not really sure why this is.

柯佳嬿 Ke Jiayan → Ko Chia-yen

田馥甄 Tian Fuzhen → Tien Fu-chen

陈建州 Chen Jianzhou → Chen Chien-chou

吴宗宪 Wu Zongxian → Wu Tsung-hsien

[20] Yi → I (sometimes)

I have seen this convention not followed pretty frequently, but two very famous names are often in line with it.

蔡英文 Cai Yingwen → Tsai Ing-wen

蔡依林 Cai Yilin → Tsai I-lin

[21] ui → uei

I have seen this convention used a couple times, but “ui” seems to be much more common.

蔡立慧 Cai Lihui → Tsai Li-huei

[22] hua → hwa

This is yet another convention that I don’t always see followed. But I know “hwa” is often used for 华 as in 中华, so it’s important to know.

霍建华 Huo Jianhua → Huo Chien-hwa

[23] uo → o

This is another example of where one might get confused between the syllables luo vs. lou or ruo vs. rou. So be careful!

罗志祥 Luo Zhixiang → Lo Chih-hsiang

刘若英 Liu Ruoying → Liu Jo-ying

徐若瑄 Xu Ruoxuan → Hsu Jo-hsuan

[24] eng → ong (feng, meng)

I think this rule is kinda cute because some people with Taiwanese accents pronounce meng and feng more like mong and fong :)

权怡凤 Quan Yifeng → Quan Yi-fong

[25] Qing → Tsing

I am not familiar with the reasoning behind this spelling, but 国立清华大学 in English is National Tsing Hua University, so this spelling definitely has precedence. But I also see Ching too for this syllable.

吴青峰 Wu Qingfeng→ Wu Tsing-fong

[26] Li → Lee

Nowadays a Chinese person from the Mainland would probably using the Li spelling, but in other areas, Lee remains more common.

李千那 Li Qianna → Lee Chien-na

[27] Qi → Chyi

I have noticed this exception. However, I’ve only personally noticed it for this surname, so maybe it’s just a convention for 齐.

齐秦 Qi Qin → Chyi Chin

齐豫 Qi Yu → Chyi Yu

[28] in ←→ ing

In Taiwanese Mandarin, these sounds can be merged, so sometimes I have noticed ling and lin, ping and pin, etc. being used in place of each other. I don’t know this for sure, but I suspect this is why singer A-Lin is not A-Ling (her Chinese name is 黄丽玲/Huang Liling).

[29] you → yu

I personally haven’t noticed these with other syllables ending in “ou,” only with the “you” syllable.

刘冠佑 Liu Guanyou → Liu Kuan-yu

曹佑宁 Cao Youning → Tsao Yu-ning

There is a lot of variation with these transliterated names. There are generally exceptions galore, so keep in mind that all this is general! Everyone has their own personal preferences. If you just look up some famous Taiwanese politicians, you will see a million spellings that don’t fit the 28 conventions above. Sometimes people might even mix Mandarin and another Chinese language while transliterating their name.

Anyway, if any of you know why 李安 is romanized as Ang Lee, please let me know because it’s driving me crazy.

Note: The romanized names I looked while writing this post at were split between two formats, capitalizing the syllable after the hyphen and not capitalizing this syllable. I chose to not capitalize for all the names for the sake of consistency. I’m guessing it’s a matter of preference.

#romanization#transliteration#taiwan#chinese name#chinese names#chinese#mandarin#chinese language#mandarin chinese#langblr#studyblr#langblog#language learning#language stuff#language study#language#languages#language lover#chinese langblr#chinese studyblr#mandarin langblr#mandarin studyblr#learn chinese#learn mandarin#learning chinese#learning mandarin#study chinese#study mandarin#studying chinese#studying mandarin

253 notes

·

View notes

Note

So how does a civil administrator like Zhuge Liang get to be the guy directing military campaigns anyway? Weren't there others in Shu more qualified?

There wasn't really a strict separation between the civil officials and military officers. Some did one thing or the other but at the upper levels a lot of people were responsible for both, at least once Han collapsed. Being able to defend your territory was essential to governing it. Many canton executors and provincial heads also held military command. The two strands didn't really start to diverge again until Sima Yan started demilitarizing Jin, and that didn't last long.

So part of it is simply that the position of chancellor also came with substantial control over the military. It was part of Zhuge Liang's parcel of authority. (Think of it somewhat like how the US president is the head of a civilian government but also commander in chief of the US armed forces).

Additionally (unless I've been reading a very bad translation), Liu Bei didn't originally give Zhuge Liang complete control over military affairs. Li Yan was also given extraordinary command and was stationed at Yong'an. However, he later acted as Zhuge Liang's subordinate (probably because the peace subsequently established with Wu meant that Yong'an did not need a commander with that much authority). Regardless, sole authority was not initially given only to Zhuge Liang.

All that aside . . . more qualified? Perhaps. It depends on what you want your chancellor doing. There weren't many people in the Shu court who would have been as effective at the state's internal management, and Zhuge Liang's administrative talents were sufficient to keep the army properly supplied, funded, and organized. It's entirely possible that Liu Bei never intended for him to actually be leading the army in the field (something he never did during Liu Bei's lifetime) and that if he had such expectations he would have chosen someone with more practical experience.

Understand, we're talking about a job whose description more or less changed with whoever held the office. People holding similar positions in Shu's subsequent years, and in Wei and Wu, all acted in their own way. These positions of broad authority meant that the office holder exercised his own discretion in how to use that authority, particularly when the sovereign was weak.

None of Shu's subsequent premiers held the same title as Zhuge Liang. Jiang Wan, Fei Yi, Jiang Wei, and Yan Yu all held a rank that I translate as Grand General (and Jiang Wan was later elevated to Grand Commander). In Han proper, this was mostly a position with control over the court. Jiang Wan and Fei Yi used it as such, while Jiang Wei acted as a field commander.

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

Alright, this prompt will be more bittersweet than putright sad. AHEM

Despite Liu Bei's reckless attack against Wu, Shu did not fall then and there. After his death from an illness, Liu Shan became Emperor. And despite not being a ruler, he had a better sense of perspective than his father. For when the kingdom of Jin (as Wei was renamed after the Sima clan took over) outmatched Shu, Liu Shan knew it was a fight he would lose, so he chose the best course of action for his people. He surrendered.

Now Baiken finds herself meeting an 73 years old Zhao Yun. Beyond all expectations, he had survived and retired. Despite being sad about the surrender, he's proud that the little baby he saved grew up to be someone who saved lives.

Zhao Yun was the last remnant of The Three Kingdoms. And poor Baiken, who despite aging mich slower, gets to see a friend fade away to the sands of time. She doesn't know whether to feel sad he's going away or feel happy that sge got something resembling the life she could have had in her village before That Man sacked it.

"I was wrong about Shan." Those are the first words out of her mouth when her eye falls on Zhao Yun, his hair gray and his face wrinkled. "Sorry about that."

"You weren't." Zhao shakes his head with a chuckle, groaning lightly as he sat up in his bed so he can meet Baiken's gaze properly, "Indeed, he did not have the ambition of Lord Liu Bei." He smiled more broadly, "perhaps that is why I'm still alive."

She chuckles, "yeah, no kidding."

She drags a chair to sit at his bedside, and takes out her gourd. "Oh, no..." He denies her, though weakly, "I'm far too old for that sort of thing..."

"Oh spare me kid," She shoves a cup into his hands, "at your age any death is natural, so lighten up."

He laughs again, coughing harshly after a moment, "O-Oh, it does me good to see you haven't changed at all, Lady Baiken." He bows his head as she fills his cup, "...indeed, barely any change at all."

"Trade secret," She smirks at him, "it doesn't include any peaches, if you're wondering."

Another laugh, gentler this time, and he drains his cup. Silence follows, the sounds of nature from outside lending it a comfortable air.

"Lord Liu Bei had a message for you, at the end." He looked at her with a mix of regret and grief, "I could never find you to give it."

"Once Jin showed up, I figured it would be wise to make myself scarce." Her mouth twisted in distaste. "There was no love lost between me and Sima Yi, and the rest of his family didn't take too kindly to me either." She shivered as she remembered an ice cold smile, "especially not that wife of his."

Another laugh, longer, followed by a harsher series of coughs. It lasts for a disconcerting length of time. At the end Baiken is gripping Yun's shoulder as he breathes in deeply and slowly.

"...His message...was that you were right, that everyone around him was right, and that he was sorry." His face twisted in agony, "My lord..."

"He was angry." She said quietly, "he was mourning...I was never angry at him...I was just frustrated that I couldn't help him after all the battles I fought and money I was paid."

Zhao Yun bows his head, tears quietly falling from him.

"...He's with his brothers now." She soothes again, "and Zhao Yun has no fucking business mourning that, right?" Another laugh is shocked from him, brief and light, "good...you've earned your rest kid, be proud of the work you did and take the damn rest, alright?"

He nods, sleepily. "...I'm sorry...I fall asleep earlier and earlier these days."

"One of the perks of getting old kiddo." She helps him back down to bed. "Sleep as much as you want, Liu Bei is waiting on you."

He's already asleep, and more besides, by the time she covers him with his blanket.

She's outside again, sitting tiredly on a hill nearby, looking up at the sky slowly growing orange as evening draws closer.

"...It would have been a good life, huh?" She says to no one, the air carrying her words to the horizon. "...I get it, alright? I get it already...I'm ready to go home."

By morning, Baiken would vanish from that hill, and no one who saw her on the battlefield during these turbulent times would ever see her again.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Biografía

Información Personal

Nombre en chino: 王一博

Edad: 23 años

Fecha de Nacimiento: 5 de Agosto de 1997

Lugar de origen: Luoyang, Henan - China

Signos Zodiacales: Leo / Buey

Estatura: 1.80 cm

Peso: 59 kg

Tipo de Sangre: AB

Educación: Hanlim Multi Art School

Información Profesional

Profesión: Actor, Cantante, Rapero y Bailarín

Agencia: Yuehua Entertainment / Starship Entertainment

Grupo K/C Pop: UNIQ

Filmografía

Dramas:

2017 - When we were young (Lin Jia Yi)

2017 - Love Actually (Zhai Zhi Wei)

2017 - Peacekeeping Infantry Battalion (Wen Shu)

2019 - Gank your heart (Ji Xiang Kong)

2019 - The Untamed (Lan Wang-Ji)

2020 - Private Shushan Collage (Teng Jing)

2020 - Super Talent / My Strange Friend (Wei Yichen)

2020 - Legend of Fei (Xie Yun)

2021 - Being a Hero (Chen Yu)

2021 - Feng Qi Luo Yang

Películas:

2016 - MBA Partners (Zhao Shu Yu)

2016 - A Chinese Odissey Part Three (”Red Boy”)

2017 - Fight for Love (Xiao Fu)

2018 - Live for Real (Lin Jin)

2018 - Crystal Sky of Yesterday (Qi Jing Xuan)

2019 - Fantasy Westward Journey

2019 - Unexpected Love (Chang Lin)

Discografía

Uniq

Discos

28.04.2015 - EOEO

Singles

2014 - Falling in Love

2014 - Born to Fight (Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles OST)

2014 - Celebrate (Pingüinos de Madagascar OST)

2015 - EOEO

2015 - Luv Again

2015 - Best Friend

2015 - Happy New Year

2015 - Erase Your Litlle Sadness (Bob Esponja La Película OST)

2016 - Falling in Love (Versión Japonesa)

2016 - My Dream (MBA Partners OST)

2017 - Once Again (Once Again OST)

2017 - Happy New Year 2017

2018 - Never Left

2018 - Next Mistake

2018 - My Special (One and Another Him OST)

2018 - Monster

Solo:

2017 - Once Again (Once Again OST)

2017 - Just Dance

2018 - The Shadow of the Shark (The Meg OST)

2018 - Heart Affairs of the Youth (Crystal Sky of Yesterday OST)

2019.01.17 - Fire

2019.03.13 - Lucky

2019 - The Coolest Adventure (Gank Your Heart OST)

2019 - Saying Sword (Moonlight Blade OST)

2019 - Wu Ji / Unrestrained (The Untamed OST)

2019 - Bu Wang / Don’t Forget (The Untamed OST)

2019.12.30 - No sense

2020 - Dear Mom (Lost in Russia OST)

2020 - With you by my Side

2020 - We Stay Together

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chinese Polymaths, 100 – 300 AD: the Tung-kuan, Taoist Dissent, and Technical Skills by Howard L. Goodman

Themes: Luoyang; Objects

Overview:

This essay is on polymathy. Goodman says that at the time this essay was written it was a new field of study. He defines the term, initially in an ancient western context, as a new kind of knowledge. This is contrasted with polydidactics which is conventional knowledge, the set texts for a given context. To cover the topic, he is going to study some well-known early scholars of China to see what skills and teachings feature in their writings. Goodman holds up Pei Songzhi up as an example of one doing this, after he rewrote a conventional history in a new way. His study will focus on three areas; cultural history, synergy among skills and the impact upon our historical methods.

Goodman begins with the Dong guan [Tung-kuan], the court institution of learning for Eastern Han. It was a building within the palace that some very limited few scholars were allowed access to. It became the centre for polymathy as debates started about textual and ritual authorities which allowed for developing new ideas and approaches. The first important scholar linked with this was Pan Gu the historian. Initially the Dong guan was just a centre for historical record keeping but gradually became a centre for other areas too. For example, before Pan Gu was arrested there was evidence he was working on mathematical astrology.

Next Goodman takes a side step away from his primary topic to look at the impact the Dong guan had on politics. While few male scholars had access, eunuchs and the Emperor’s harem did and this may have led to the struggles between the two factions. This is because the scholars who did have access were those who had deigned to take a low paid job and position within the court – there was no formal role; however, it was deemed worth it because of the rare selection of books that were kept within.

When Goodman gets to the reign of Emperor Huan, he says that Daoism and Daoist rites became increasingly used by the Court. The Dong guan as a result became known as a centre for the study of Daoist texts. Goodman is keen to make a distinction between the mainstream Daoism and the Neo-Daoism of various rebel groups that arose around the same time. Suggesting that the Daoism of the scholars was more academic and was probably not practised in their private religion Scholars wished to be appointed to the Dong guan as it allowed them to be paid to further their studies without having to engage in factional strife, and Goodman gives an overview and examples of scholars who were executed for speaking out against the eunuchs, including a long section on Cai Yong who headed up the Dong guan until his death.

Goodman turns to astrology and court music. However, he points out that both of these were tied to rites and therefore legitimacy and so during the days of a falling dynasty these were perilous things to be studying as implications of disloyalty were never far away. Cai Yong led an attempt to try and rediscover a style of court music. The success (or lack) of the attempt itself is unimportant to Goodman’s study what he is interested in is the presence of a research program which “pushed the polymath envelope.”

The Dong guan and most of its material was destroyed in the fire in Luoyang set by Dong Zhuo so there was a period where it didn’t exist. Many years later the Imperial Library of Wei filled the gap, while in Wu and Shu some sort of Dong guan was established – Chen Shou was appointed to Shu’s. Western Jin created a formalised role called a Gentleman drafter, a change from the unofficial role in the Han. They were placed under the direction of the Imperial Library.

Between the burning of Luoyang and the Imperial Library assuming the role originally filled by the Dong guan, polymathy occurred more in local “schools”. Guan Lu, described as an outsider, is used as a case study to examine how this happened. After studying what he believed, Goodman contrasts him with Cai Yong. The later searched for knowledge in historical texts and ceremonial rites whereas Guan Lu used divination.

Goodman turns to study a third polymath. This one is Xun Xu. He spends some time describing the Xun clan. Goodman notes that Xun’s writings didn’t talk about Daoist or Confucian ideas, which was different to his direct contemporaries, and also different to the Dong guan school. However, Goodman argues that his polymathy grew out of the Dong guan school, this is because of the way he was informed by ancient devices and crossed bureaucratic lines, just as Cai Yong did. He was in charge of the Imperial library until he fell foul of politics.

The conclusion contrasts Roman polymaths with Ancient Chinese ones. One of the big differences he picks up on is how in the East the opportunities to make their mark as a polymath was inside the court. What made them worthy of study though, in this field was the way they approached science and rites with attitudes and methods that had no pedigree, developing techniques that later Tang polymaths built upon.

Analysis:

This is an incredibly technical essay. For those who are interested in the development of thought in the Han dynasty it is a truly great piece. It also provides an insight into the world of Cai Yong and the prominent Xun clan. Its discussion of the Dong guan school also provides another angle into the Eunuch vs scholar struggle. However, political history is not the primary aim of this study and if that is your area of interest you have to wade through a lot of other detail to find nuggets.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Random 3k thoughts and opinions

So, while I was away for three weeks due to no internet and BT’s terrible service, I decided to play some 3k games/media and here are some random thoughts.

First, Dynasty Warriors 7 and XL - still the best DW game, hands down.

The whole benevolence thing in Dynasty Warriors 7 would be somewhat fixed if they defined it as “caring for the people’s welfare” rather than “the feelings of the people”; it would keep the sentiment while actually making sense. Aside from that, the Shu story isn’t the worst.

The Wu story is interesting, even if Sun Quan lacks in the character department somewhat (also, DIng Feng in the ending of Dongxing in 7XL is sad and a good character moment - however they still need more later Wu officers, such as Zhuge Ke and Sun Chen).

The Wei story is the Wei story. Enough said, although the ending is still perhaps the best ending.

The addition of Jin is great, although it is amusing that 3 of the characters they added (Zhuge Dan, Xiahou Ba and Zhong Hui) were killed by what the game defines as “Jin”.

Then, due to be being interested in the “Jin” story for reasons I’ll get to in a minute, I decided to see how Dynasty Warriors 8 handled it.

Badly is the key word. How is it easier to save Xiahou Ba than it is to get the Battle of Hefei Castle? Jia Chong exists to steal the roles of Wang Yuanji and Zhong Hui. Deng Ai barely says anything, which is sad. Zhuge Dan is just worse, and his rebellion (my favourite Jin stage in 7) is a boring, non nonsensical stage.

Concering the hypotheticals, the fact that if you do all the requirements but then go historical means that the game struggles to come up with a reason why it happens. Like Xiahou Ba fleeing after Sima Shi dies, for some reason, and then launching a campaign against Wei (which makes less sense than it would do if you didn’t “save” him).

Speaking of Jin hypotheticals, hey, at least it has the Conquest of Wu!

Finally, I played one other 3k bit of media, and it just so happens to be engaging and interesting, not to mention the best coverage the second half of the period has seemingly gotten. I am, of course, referring to the Legend of Cao Cao mod, Legend of Jiang Wei.

It helps I like the original and the gameplay style. The characters are interesting, and it raises issues and factors I would have never have considered (like how Shu Han had three power groups). It’s a shame that this part of then period doesn’t get as much coverage.

It’s a shame that the hypothetical path, atleast early on, is effected by leveling issues, which existed in the base game too, so I can’t be too angry.

Also, I can’t seem to “win” Zhong Hui’s rebellion which will always be funny to me.

Now, if you’ll excuse me, I’m gonna play Romance of the Three Kingdoms X for the first time, I got Cao Zhi on the personality test.

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

for the dw asks, 1, 2, 3, and 4

1. Considering the fourth question is about my favourite strategist and how often I already harp on about him, I’m going to avoid going for the obvious choice and say Sun Ce. He’s just fun to watch, listen to and play. He has great relationships with the other characters he interacts with and I have incredibly fond memories of playing Wu’s early levels in 6 where he was the commander.

2. Wu for a variety of reasons. Wu has some of my favourite characters and there aren’t too many I actually hate. Their story is the most interesting to me, and frankly Sun Ce and Zhou Yu could make anything better. Despite Koei’s attempts to shaft them in favour of Shu and Wei, they’re just too likeable. I also love the dynamic between their various strategists, with the feeling of each one being forced to pass down the torch after the various tragedies they faced. I’ve always hated the way that the Jin stage where you invade Wu/the Wei hypothetical where you invade the broken Wu just feel so anticlimactic compared to the invasions of Shu.

3. Cao Cao, for obvious reasons, but I want to take a moment to talk about Sun Quan because of the potential he has. If he was given more attention by the writers he could really become a character Liu Shan-like character. He’s someone who’s been forced into his position after watching both his father and older brother die before him, he’s left with the fear that he’ll never live up to the reputation of his family members and now they’re no longer around to console him about it. He’s left with the goal of his father and brother not even knowing whether he truly believes in it or not. If I was the one writing him I’d focus on those aspects as well as making it clear how much he relies on the others around him and especially how him slowly pushing these people away leads to his downfall. If I were given complete control I’d even add a plot point where long after Liu Bei’s and Cao Cao’s deaths and near the end of his own life, Sun Quan’s now lost his interest or passion for fighting Shu and Wei. After spending so long fighting against Liu Bei and Cao Cao, it just doesn’t feel the same now that he’s fighting their sons, the same hatred and respect isn’t there, possibly even feeling like he’s lived too long. They’re faceless to him, compared to how larger than life his previous opponents seemed.

4.

Xun Yu

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Before the War of Eight Kings, Part 1

Just posting this to get it out of the way, I didn’t even manage to get to the death of Emperor Wu. Opinions are my own. I make no excuses.

King vs. Prince

The earliest Chinese rulers were called wang 王, as a hereditary ruler of an independent state, the most obvious translation of 王 is “King”. Later on, at the end of the Warring States era, the 王 of Qin conquered all the other Chinese kings, and invented a new title for himself, huang-di皇帝, which is usually translated “Emperor”. Qin was destroyed just a few decades later by an alliance of rebel generals who again took the title of 王 for themselves. In the end, the 王 of Han conquered the other 王, and declared himself Emperor. He made his sons 王 to rule over various conquered territories as vassals to the Emperor. Later Emperors continued to give out this title to their sons, but over time all their powers were stripped away. So basically what happened was that the Emperor sent away all his sons, except the heir to the throne, to pretend to rule over territories actually governed by officials appointed by the Emperor. It is actually quite similar to modern European royal families. The Duke of Sussex doesn't actually rule over Sussex. For these people translating 王 as “King” doesn't really fit that well, which is why “Prince” is often used as well. But at the same time rulers of foreign states continued to be called 王. The issue is further confused by a third use of the title, as a stepping stone to declaring yourself Emperor. At the end of Han, Cao Cao, Sun Quan and Liu Bei three at various stages took the title of 王. One of the privileges of being an amateur is that you can do what you like, so I have decided to always translate 王 as King. Create Assembly has chosen to use Prince. But you should know that it really exactly the same word, it is just a choice of translation.

War of the Eight Kings

The Book of Jin is a history book written in the early 7th century, based on earlier now mostly lost books. It covers the history of the Western and Eastern Jin empires from 266 to 420 AD, and is divided into 130 Scrolls (or “Chapters”). From 291 to 306. the ruling family of the Western Jin Empire tore itself apart in a series of internal conflicts, eventually ending with the full collapse of the empire. Scroll 59 of the Book of Jin has biographies for the eight members of the Jin imperial family that had leading roles in these conflicts:

Sima Liang, King of Runan (d. 291) Sima Wei, King of Chu (b. 271, d. 291) Sima Lun, King of Zhao (d. 301) Sima Jiong, King of Qi (d. 302) Sima Ai, King of Changsha (b. 277, d. 304) Sima Ying, King of Chengdu (b. 279, d. 306) Sima Yong, King of Hejian (d. 306) Sima Yue, King of Donghai (d. 311)

Because of that, the whole time period has become know as the “War of Eight Kings”, but this is not really a very accurate description. First of all, all eight kings were never active at the same time, the youngest ones were just kids when the first ones got killed. It was also not just one war, but rather a series of palace coups, which escalated into a series of short civil wars, which escalated into a big messy civil war and general rebellion. I sometimes call the period for the “Jin civil wars”. War of Eight Kings sounds much cooler though.

Rise of the Sima clan, reign of Emperor Wu

I won't go into too much detail here on the rise to power of the Sima clan, and their takeover of of the Wei empire, the most of powerful of the Three Kingdoms. Sufficient to say, is that in 249 Sima Yi, one of Wei's leading generals and statesmen, and co-regent to the Emperor, launched a coup to effectively take control of the government of Wei. When Sima Yi died in 251, power passed to his oldest son, Sima Shi. And when Sima Shi died without sons in 255, power passed to his younger brother Sima Zhao. By the end of 260 Sima Zhao had done away with the last of his rivals, and installed a puppet emperor of his own choosing. In 263 his generals conquered Shu and Liu Shan's Han empire. On 2 May 264 he was granted the title King of Jin. Sima Zhao died 6 September 265. Sima Zhao was inherited by his oldest son Sima Yan, who quickly went through the final steps to replacing Wei, like Wei had previously replaced Han. The final Emperor of Wei abdicated 4 February 266, and on 8 February Sima Yan formally ascended the throne as Emperor of Jin. He has become best known under his posthumous title Emperor Wu – the “Martial Emperor”. Views on Emperor Wu is usually reduced to someone who indulged himself with a massive harem, while instituting policies that would eventually doom his empire. But compared to his predecessors, his almost 25 year long reign was a hallmark of stability. While court intrigues were sometimes quite fierce, in the end there were no political executions. And in 280 Jin's generals quickly overwhelmed Sun Hao's Wu empire in a massive invasion that reunited most territories of the old Han empire.

Position of the Sima princes within the empire

First the Han and then the Wei Emperors had kept their relatives out of political power, and instead sent them away with empty noble titles. This had the benefit of stopping them from interfering in the government and challenging the Emperor's authority. But it had the big downside of isolating the Emperor from his natural allies against takeovers from outside the imperial family. This meant that if the Emperor was a child, or otherwise incapable or uninterested in ruling, there was a power vacuum waiting for an outsider to fill. During the Han, the court had often been dominated by the Empress' family. During Wei nobody had been able to stop the Sima family from taking over. It turned out that while all the officials of course professed their absolute loyalty to the Emperor, most of them did not really mind someone not the Emperor being actually in charge. Based on these lessons, Emperor Wu decided to deeply involve his family in running the empire. First of all, at the beginning of his reigns he gave all his male relatives the Sima clan titles as kings. All descendants of his great grandfather Sima Fang were included. Sima Fang had eight sons, Sima Yi had nine sons, and Sima Zhao also had nine sons. So altogether there were quite a lot of them. I will try to include small family trees with those who become relevant.Having made his relatives Kings, Emperor Wu then also increased their privileges compared to what imperial relatives had enjoyed during Han and Wei. He gave the some say in appointments to their fiefs, the right to a personal armed guard, and let them stay in the imperial capital at Luoyang rather than requiring them to go and look after their fiefs, but most importantly he gave them important appointments at court and command of armies in the field. Sima Liang's political power did not come from his title as the notional King of Runan, but the important offices he held, and because he was the Emperor's trusted granduncle.

Sima Zhong becomes Heir

Emperor Wu had altogether twenty-six sons, but only nine survived to adulthood. His first wife was Yang Yan from the prestigious Yang clan of Hongnong. They had three sons, all born before he became emperor. The oldest died young, but the two others survived, these were Sima Zhong (b. 259) and Sima Jian (b. 262). When at the founding of Jin, Emperor Wu made Yang Yan his Empress, and almost exactly a year later, on 4 February 267, he formally established Sima Zhong as his heir to the throne. Sima Zhong was then seven or eight years old. On 2 April 272 Sima Zhong was married to Jia Nanfeng (b. 257), daughter of Jia Chong (d. 282), one of the most prominent men in the empire. Sima Zhong was then twelve or thirteen years old, she was two years older. In theory, the Emperor, as an autocrat with absolute power, could designate whoever he wanted as heir to the throne, but culturally the expectation was that the Emperor's oldest son with his Empress should inherit. There had not been a regularly appointed heir since Cao Rui. Quickly designating his oldest son as the heir signalled that the Jin empire would be run along orthodox lines. There was also the general fickleness of life to consider. Life expectancy in the 3rd century was much shorter than it is today, and mortality at all ages was much higher. There was no guarantee Emperor Wu would live to see his children grow up. Having an heir already in place, whose legitimacy was unassailable and who was connected by marriage to one of the leading families of the times, should have left the succession a settled question.

16 notes

·

View notes

Note

Who are your favorite characters of Dynasty Warriors? Do you have any ships?

Hey, thanks for the ask! Am not the greatest with words but i’ll do my best to get my points across in simple ways.

I do have a few favorites across each kingdom. From Wu would be Xu Sheng & Lu Xun; From Wei Cai Wenji; Wen Yang, Wang Yuanji and Xin Xianying from Jin; Lu lingqi from Others. As for Shu, Jiang Wei and Ma Chao, and my top favorite of all- Has always been and still is Zhao Yun.

I admit, his looks got me good back in DW5 (and movesets). I also admit that Koei didn’t give him enough personality aside from being brave and loyal. So perhaps it isn’t so much of an in game factor that made me fell for him so hard; I’ve been using DW as an escape and naturally he became a.. Comfort character.

To me he did get some upgrade from DW7 onwards, not just in terms of characteristics but expressions + body language as well. Although i’ve not played DW7, but from bits of information/cutscenes show that he is in fact a very motherly figure- The kind of dad that would sit down and have tea party with his kids, combing/tying his kids’ hair or have a pillow talk with them at night. While in DW8′s ambition mode, his stables dialogue hinted that he can be equally compassionate towards animals. I have a soft spot for tough guys who are gentle with little creatures, SO YEA THAT GOT ME AGAIN.

And in DW9, his interaction with Zhou Cang, judgmental much? Lol. Never thought i’d see him that way. Plus, this installment would be the first time i’ve seen him express this much amount of sorrow, especially that post-Yiling cutscene. I like to see him as not being afraid to show emotions, crying isn’t weak at all. The way he gets more and more humane, I like that.

As for ships, generally all of the canon couples have their own special dynamics. If I had to pick one it would be Zhang Chunhua and Sima Yi. Chunhua is an alluring woman, intimidating mom and wife at the same time. She don’t (only) appear for the sake of fan service, she actually compliments Sima Yi and gave him a whole new role as a dad and husband. We even get to explore more interesting sides of him thanks to her.

The non-canon couple I adore is Yu jin x Cai wenji. DW8XL’s stage, definitely that to blame. A stern man paired with a sweet, oblivious lady, the contrast in their characters is so amusing. Wenji being dense while Yu Jin wants to be mad at her but he can’t. What cute dorks :”D Imagine Yu Jin being so flustered that he can’t seem to function whenever Wenji does something cute. Simply present him a flower and he shall short circuit.

That should be all. Hopefully you find this an okay read, appreciate your ask! Was going to return the favor but i think it’s obvious that the answer to your favorite is Xun You lol.

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

Was Liu Bei actually descended from the Han or was that just something he made up?

Honestly, who cares?

He claimed to be descended from Emperor Jing. Maybe that was true, maybe it was just a family legend. Everyone likes having a famous ancestor and if you're a Liu you can pick anyone you want.

SGZ 32 (his biography) presents the claim. Most people seem to accept it uncritically. I think that's a mistake but it doesn't really matter.

The real question is: what is the practical relevance of this claim? Did it do anything for Liu Bei and if not, does it even matter? That quickly becomes a matter of opinion. I'll start with things I think we can safely call factual.

The most immediate use for such a claim is, of course, to present Liu Bei as a genuine scion of Han's founding line, which in turn allows him and his supporters to claim some form of legal legitimacy for their state. Guangwu, Han's second founder, was only distantly related to the previous ruling branch and Liu Bei's claim set him in the same mold. This is the same justification later used by Sima Rui at the dawn of Eastern Jin. It's as good an argument as any other he could have made.

It may have also earned him some good will from people he needed favors from; particularly in Jing. Liu Biao also claimed to be descended from Emperor Jing and although this wouldn't make him at all closely related to Liu Bei (Emperor Jing died 302 years before Liu Bei was born), it was a foot in the door. It likely garnered him some popular support by allowing him to claim a closer connection to Liu Biao and the distant Han emperor than he really had, though that is just speculation. Evidently he was able to leverage it enough that he was allowed to adopt Kou Feng, a distant imperial relative on his mother's side; such adoptions were typically only done between family members so we can see Liu Bei presenting himself as a matrilineal uncle by virtue of his distant heritage.

The question remains, did any of that matter? It probably was of some use in Jing (as stated above), and in that case it doesn't matter if it's true or not. It was a way for Liu Bei to inject himself into the local affairs and society, a way to get this foot in the door. That's a job it does just as well whether it's true or false.

The idea of dynastic legitimacy is a bigger question. One of the core arguments for Shu's legitimacy was that Liu Bei was a Han scion and - as the last Han scion with any power - it was up to him to restore the dynasty just like Guangwu. That argument, of course, relies upon Liu Bei's claim being true.

But I'm not convinced that matters either. Whatever arguments the scholars in Wei, Wu, and Shu put forward, they're ultimately just that well-known velvet glove over the iron fist. The founders of these states were warlords, people who came to power purely through force of arms and sought to take control of more land in the same fashion.

Court scholars loved to debate questions of legitimacy and succession. Maybe some of them actually even care. But I'm a cynical man and never believe that politicians buy into their own bullshit (unless they're full-on crazy). Liu Bei and his court knew that the story was just a piece of propaganda they needed to help prop up their argument. True? False? That's irrelevant. The truth doesn't matter in such a situation.

And while it's fun for scholars to debate questions of dynastic legitimacy, I haven't seen any evidence that this claim gained Liu Bei any significant support. There weren't significant defections from Wei and Wu in the name of the "rightful emperor." I'm sure you can dig up a couple edge cases, but defections by the like of Meng Da, Huang Quan, and many leaders in Nanzhong show that this claim did not particularly inspire loyalty.

As a thought exercise, I'll also note that Liu Zhang was still alive and that Sun Quan named him as Inspector of Yi in opposition to Liu Bei. Liu Zhang was also a Han scion, as much as Liu Bei was. And he only lost control of Yi because Liu Bei betrayed him. He had as much right to the Han throne as Liu Bei himself did.

Anyway. Was it true or not? I can't see how it matters. You might as well accept the story as presented in SGZ 32; it doesn't make a crumb of difference one way or another. The entire concept of dynastic legitimacy is invented to justify rule by a hereditary military dictatorship; the Divine Right of Kings with more paperwork. One is as legitimate as the next.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lu Ji’s “Discourse on the Fall of Wu (Part 2)”

The second part of this post.

其下篇曰:昔三方之王也,魏人據中夏,漢氏有岷、益,吳制荊、揚而掩有交、廣。曹氏雖功濟諸華,虐亦深矣,其人怨。劉翁因險以飾智,功已薄矣,其俗陋。夫吳,桓王基之以武,太祖成之以德,聰明睿達,懿度弘遠矣。其求賢如弗及,血阝人如稚子,接士盡盛德之容,親仁罄丹府之愛。拔呂蒙於戎行,試潘浚於系虜。推誠信士,不恤人之我欺;量能授器,不患權之我偪。執鞭鞠躬,以重陸公之威;悉委武衛,以濟周瑜之師。卑宮菲食,豐功臣之賞;披懷虛己,納謨士之算。故魯肅一面而自托,士燮蒙險而效命。高張公之德,而省游田之娛;賢諸葛之言,而割情欲之歡;感陸公之規,而除刑法之煩;奇劉基之議,而作三爵之誓;屏氣跼蹐,以伺子明之疾;分滋損甘,以育淩統之孤;登壇慷愾,歸魯子之功;削投怨言,信子瑜之節。是以忠臣競盡其謨,志士咸得肆力,洪規遠略,固不厭夫區區者也。故百官苟合,庶務未遑。

And in the second part he wrote:

"Formerly, the realm was split into three kingdoms. The people of Wei occupied the Central Plains, the clan of Han possessed the regions of Min and Yizhou, while Wu controlled the provinces of Jingzhou and Yangzhou and spread to grasp the lands of Jiaozhou and Guangzhou. But although the Cao family had performed outstanding achievements among the Xia (ethnic Han) people, their cruelty was just as great, stirring up the people's hatred against them. As for the old codger Liu (Liu Bei), though he controlled difficult terrain and had pretensions to cleverness, his achievements were slight things, and his state was a mean and vulgar one. It was very different with Wu, which had its foundation laid down by the martial feats of King Huan (Sun Ce) and completed by the virtues of Taizu (Sun Quan).

"How numerous were Taizu's good qualities! He was intelligent and wise, astute and perceptive; he was understanding and measured, generous and farsighted. He sought out worthy people as though worried that he would never have enough of them, and he sympathized with the people as though they were his own children; he drew people in with complete demonstrations of his abundant virtues, and he exhibited kinship and benevolence through utter displays of love and affection. From out of the rank and file of the soldiers did he pluck Lü Meng; from among the masses of the captives did he recruit Pan Jun. He was ever sincere and invariably trusting, with no reservations that we might be swindled or cheated; he was always taking the full measure of a person and employing them according to their full potential, with no suspicion that his proteges might turn against us.

"He could confer the whip of authority upon others, as displayed by the power he granted to Lord Lu (Lu Xun); he could entrust the military defense of the state to subordinates, as exhibited by the army he assigned to Zhou Yu. He lived in a humble palace and ate meager fare, so that he might richly reward the achievements of his subjects; he was modest and unassuming about himself, the better to accept the plans and strategies of his advisors. Thus did Lu Su join him after only a single meeting; thus did Shi Yue yield to his rule despite the natural defenses of his own domain.

"He respected Lord Zhang's (Zhang Zhao's) virtues and so dispensed with the frivolities of wandering and hunting; he honored Zhuge Jin's advice and so reduced indulging his personal wishes and desires; he was moved by Lord Lu's (Lu Xun's) arguments and so mitigated the burdens of the laws and punishments; he was impressed by Liu Ji's criticism and so swore 'the oath of the three cups' (to ignore his commands while drunk). Holding his breath and treading silently, he peered through the gap in the wall to observe Ziming (Lü Meng) on his sickbed; fighting back tears and denying himself delicacies, he adopted the orphans of Ling Tong; ascending the altar and overwhelmed by emotion, he recalled the achievements of Lu Zijing (Lu Su); dismissing and denying words of slander, he trusted in the good faith of Ziyu (Zhuge Jin).

"His loyal ministers all exhausted their minds for his sake, and his ambitious subjects all devoted their full strength to his cause. His aims and ambitions were distant and lofty indeed, nor was he content to restrict himself to a small domain. And for that reason, his offices of state formed quite the collection, nor had he ever any respite from his affairs.

初都建鄴,群臣請備禮秩,天子辭而弗許,曰:「天下其謂朕何!」宮室輿服,蓋慊如也。爰及中葉,天人之分既定,故百度之缺粗修,雖醲化懿綱,未齒乎上代,抑其體國經邦之具,亦足以為政矣。地方幾萬里,帶甲將百萬,其野沃,其兵練,其器利,其財豐;東負滄海,西阻險塞,長江制其區宇,峻山帶其封域,國家之利未見有弘於茲者也。借使守之以道,禦之以術,敦率遺典,勤人謹政,修定策,守常險,則可以長世永年,未有危亡之患也。

"When the capital was first established at Jianye (in 229), Taizu's ministers asked him to prepare the rites and offices at the usual glorious standards, but he declined and would not agree, saying, 'What would the realm say of me?' And his palaces and chambers, his carriages and clothing, were all kept accordingly frugal. For since the world was experiencing a new era and the division of the realm was a fact, Taizu established the imperial offices on a modest basis and rarely added to their luster. Though there was a gradual increase in finery, it never reached the excesses of past dynasties; though Taizu reduced the forms of government affairs, they were still sufficient for the administration of the state.

"Was not Wu remarkable in those days? Its territory encompassed about ten thousand li, and its army boasted a million armored soldiers. Its fields were fertile, its soldiers were disciplined, its weapons were keen, and its resources were rich. To the east it hugged the wine-dark sea, and to the west it straddled the mountains and gorges; the Yangzi girded its border, and the steep mountains guarded its fiefs and regions. Never before had the state enjoyed such great and abundant advantages.

"If only its later rulers had perpetuated such a system and kept up its practices! If only they had led the people to preserve the laws, acted cautious in their conduct and circumspect in their government, maintained and defined the policies of state, and closely guarded and observed the avenues of approach. Then Wu could have continued to exist, down the years and through the ages, without the slightest worry of destruction or collapse.

或曰:「吳、蜀脣齒之國也,夫蜀滅吳亡,理則然矣。」夫蜀,蓋籓援之與國,而非吳人之存亡也。其郊境之接,重山積險,陸無長轂之徑;川厄流迅,水有驚波之艱。雖有銳師百萬,啟行不過千夫;軸轤千里,前驅不過百艦。故劉氏之伐,陸公喻之長蛇,其勢然也。昔蜀之初亡,朝臣異謀,或欲積石以險其流,或欲機械以禦其變。天子總群議以諮之大司馬陸公,公以四瀆天地之所以節宣其氣,固無可遏之理,而機械則彼我所共,彼若棄長技以就所屈,即荊、楚而爭舟楫之用,是天贊我也,將謹守峽口以待擒耳。逮步闡之亂,憑寶城以延強寇,資重幣以誘群蠻。于時大邦之眾,雲翔電發,懸旍江介,築壘遵渚,衿帶要害,以止吳人之西,巴、漢舟師,沿江東下。陸公偏師三萬,北據東坑,深溝高壘,按甲養威。反虜宛跡待戮,而不敢北窺生路,強寇敗績宵遁,喪師太半。分命銳師五千,西禦水軍,東西同捷,獻俘萬計。信哉賢人之謀,豈欺我哉!自是烽燧罕驚,封域寡虞。陸公沒而潛謀兆,吳釁深而六師駭。夫太康之役,眾未盛乎曩日之師;廣州之亂,禍有愈乎向時之難,而邦家顛覆,宗廟為墟。嗚呼!「人之雲亡,邦國殄瘁」,不其然歟!

"There are those who argue that 'Wu and Shu needed each other like the teeth need the lips; the destruction of Shu meant that Wu's fall was only a matter of time'. Now it was certainly a benefit to Wu to have Shu as its ally and helper. Yet Shu was not so critical to Wu that only through its existence could Wu survive. The border regions of Wu were sufficient in themselves to hold out against any foe. We had our share of many mountains and cliffs, so that nowhere was there any broad avenue of advance upon land, and our rivers had narrow points and swift currents, not to mention the difficulties posed by terrifying waves. Even if the enemy had an army of a million soldiers altogether, the terrain of our land meant that the heads of their columns could never exceed a thousand men; the enemy might amass a navy of a thousand ships, but its vanguard on the water could never surpass a hundred boats. And it was for this very reason that, when the Liu clan campaigned against us (at Yiling in 222), Lord Lu (Lu Xun) compared their army to a massive snake, unable to concentrate all its power at any one point.

"When Shu first fell (in 263-264), our court ministers had various ideas of how we ought to respond. Some proposed checking the flow of the Yangzi by piling stones and boulders in it, while others advocated for setting up barriers and barricades across the river to guard against any developments. The Son of Heaven (Sun Xiu) convened an assembly to solicit the advice of the Grand Marshal, Lord Lu (Lu Kang). Lord Lu told them that, as the Yangzi was one of the Four Rivers (the Yellow River, the Huai River, the Ji River, and the Yangzi) whereby Heaven and Earth make manifest their power, any proposal to dam the river would be doomed to failure. He also argued against building any barricades, saying that they would be an obstruction to us as much as to the enemy; if our foes should ever cede their current advantage and appear weak, then we could use the Yangzi as our own avenue of invasion against them by having the navies of the Jingzhu and Chu regions row upstream. For the Yangzi was a treasure bestowed upon us by Heaven, as he said, and the best thing to do would be to carefully maintain our existing garrisons among the gorges and mouths of the river and wait for the momentum of war to shift in our favor.

"When Bu Chan rebelled against us (in 272), he offered up a valuable city to entice a powerful enemy (Jin) to invade, and he distributed heavy bribes to induce the Man tribes to rise against us. At that time, the vast forces of our enemy gathered together like clouds and advanced like lightning, pouring down upon the banks of the Yangzi; they built ramparts along the river and occupied critical places in order to halt our advance west, and they dispatched their fleet in the Ba and Han regions east down the Yangzi against us. Yet Lord Lu (Lu Kang) led a force of thirty thousand soldiers to occupy Dongkang to the north (of Bu Chan's base at Xiling), where he deepened the moats and raised the ramparts, maintained his soldiers and magnified his aura. The rebel swine (Bu Chan) simply huddled up in his city and waited for death, never daring to march north and take a chance on survival; our powerful foe suffered a great defeat and fled through the night, losing more than half their army. Lord Lu split off a detachment of five thousand keen soldiers and sent them west to block the arrival of the enemy's fleet. He triumped everywhere, east and west, and he took captives and prisoners by the tens of thousands. Such was the genius of this man's planning; would he ever have steered us wrong? And in the years following, there were rarely any disturbances which might have required the signal fires and hardly any concerns within the state.

"It was after Lord Lu left us (in 274) that our fortunes and our planning ebbed. Wu became engulfed by deep divisions, and our armies were gripped by defeatism and despair. In the invasion of the Taikang era (by Jin in 280), the enemy's forces were no greater than in former times, nor were the disturbances we experienced in Guangzhou (during the rebellion of 279) any worse than difficulies Wu had faced before. Yet the state toppled and collapsed, and the ancestral temple was left in ruins. Alas! 'Once good men have all departed, the state never lasts for long.' Was it not so?

《易》曰「湯、武革命順乎天」,或曰「亂不極則治不形」,言帝王之因天時也。古人有言曰「天時不如地利」,《易》曰「王侯設險以守其國」,言為國之恃險也。又曰「地利不如人和」,「在德不在險」,言守險之在人也。吳之興也,參而由焉,孫卿所謂合其參者也。及其亡也,恃險而已,又孫卿所謂舍其參者也。夫四州之萌非無眾也,大江以南非乏俊也,山川之險易守也,勁利之器易用也,先政之策易修也,功不興而禍遘何哉?所以用之者失也。故先王達經國之長規,審存亡之至數,謙己以安百姓,敦惠以致人和,寬沖以誘俊乂之謀,慈和以結士庶之愛。是以其安也,則黎元與之同慶,及其危也,則兆庶與之同患。安與眾同慶,則其危不可得也;危與下同患,則其難不足血阝也。夫然,故能保其社稷而固其土宇,《麥秀》無悲殷之思,《黍離》無湣周之感也。

"It may be true that the Book of Changes states, 'It was in accordance with the will of Heaven that Tang of Shang and King Wu of Zhou accepted the Mandate.' And someone did once say, 'An age of order will not take shape until the age of turmoil has reached its zenith.' Such things are indications of the importance which the sovereigns of old placed upon the circumstances of the age. Yet it is also true that the ancients tell us that 'Circumstance is not so important as favorable terrain', and when the Book of Changes speaks of 'the kings and nobles employing their natural defenses to safeguard the state', this too is an emphasis on such natural terrain. But greater still than either of these is common purpose among the people, for as the ancients assure us, 'Favorable terrain means less than a united will'. We are instructed to place our faith 'in virtue, not in terrain' because it is through the people that our defenses can be held at all. When Wu rose, it was because it observed all three of these aspects, and acted fully in accordance with the principles illustrated by Minister Sun (Xunzi); when Wu fell, it was because it focused on natural defenses to the exclusion of all else, violating the system that Minister Sun had laid out.

"The four provinces of Wu (Yangzhou, Jingzhou, Guangzhou, and Jiaozhou) had no shortage of manpower; the lands south of the Yangzi did not lack for talents. The natural terrain of our mountains and rivers were well-suited for defense, and our military equipment was neither dull nor difficult to use. We could easily have maintained the same practices which had worked for our ancestors. Why then did we fail? Why did we suffer calamity? It was because, though we had the means, we failed to use them.

"It was for such reasons that the kings of old were always sure to fortify their states by cultivating good traditions, and they studied the rises and falls of states across time. They were modest about themselves in order to reassure the people, and they were kind to the population in order to achieve harmony; they were open of hand in order to attract the advice of talented and righteous people, and they were kind of heart in order to bind the people to them with love. When this situation prevailed, then in times of peace the people shared in their joy, and in times of danger the populace shared in their sorrow. When joy is shared by all during peace, then even danger can pose no threat; when sorrows are held in common, then even chaos will never descend into bloodshed.

"If only this had been the case in our final years. Then we could have preserved our altars of state and protected our territory, and none among us would have experienced the agony of the Barley Ears poem or felt the despair of the Drooping Millet poem."

#Wu#Eastern Wu#Three Kingdoms#Sanguo#Lu Xun#Lu Kang#Lu Ji#Jin Dynasty#Western Jin#Chinese History#China

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Character Analysis: Liu Shan

My favorite male character, and the only one that managed to bring me to tears.

If you call him Liu Chan you’re an egg.

Appearance:

I’m gonna say it right here. I am awful at analyzing male outfits. I am a huge sucker for girl’s fashion but when it comes to guy’s fashion and designing outfits? I’m clueless.

Liu Shan looks fantastic and royal and I’m glad they did away with the oversized fur collar thing. Also I find it hilarious that his ‘special’ expression in 8 (Usually a blushy, embarrassed one for most people) is just

An internally dead stare. He’s done with Jiang Wei’s shit.

I also like how they managed to make him seem almost, what’s the word, distant? Despite all of his attempts at showing expression and being emotional, he still comes off as being far away from reality, like he’s either faking (AKA DW7 and 8) or just really morally conflicted and depressed (DW9)

Weapon:

It’s a rapier. Its a sword commonly associated with royalty/nobility. The chains are simple but powerful in the old games. In 9, it’s easy to streamline and has a nice range of electric stuff. No complaints.

No. Don’t talk about the bench. That WAS SUPPOSED TO BE FOR JIAN YONG WHY ISN’T JIAN YONG IN THE GAMES YET IT WAS SO PERFECT was an affront to humanity.

Personality:

Here’s the good stuff.

Liu Shan’s personality in the transition from 7/8 to 9 changed a lot. While 7/8 portrays him more as a silent manipulator who acts foolish to hide his true nature (Which was pretty cool on it’s own, and a nice deviant from history), 9 definitely makes him more vulnerable and confused, in a way that makes me feel truly sympathetic for him.

What resonated with me so much was how human he seemed. He wasn’t being preachy about benevolence every two seconds, he wasn’t being tough, he wasn’t being evil. He was honest with his feelings and his thoughts.

Liu Shan is noted for being incredibly passive here, and the reason why? At first (About until Zhuge Liang dies), it’s because he’s young and inexperienced. Liu Bei died when he was 17. Not exactly the ideal age to suddenly pick up a new dynasty and the responsibilities of a father that did a lot of stuff. Plus, Liu Bei doesn’t exactly spend a lot of time with his son (As in, they literally never speak.) so Liu Shan never learned anything from him.

After Liu Shan gains experience, though, he tries his hardest to get his views through. He’s constantly trying to tell Jiang Wei that his methods are violent, that maybe the fighting isn’t necessary, that there has to be a better way to do things, but nobody will listen to him or heed his words, as they’re too buried in trying to honor those that came before them.

As Zhuge Liang and Jiang Wei continuously fail campaign after campaign, Liu Shan starts to grow stressed. The common people hate that so many soldiers are being sent off to die, and lots of money and resources are spent on constant losing battles. The government needs to be restructured, and tensions with Wu are still pretty high despite the shaky alliance.

Eventually, things are falling apart. All of the people he depended on started to die off (Zhao Yun, Ma Chao, Zhang Bao, Guan Suo and Xing) and he’s now stuck in-between the bickering of Huang Hao and Jiang Wei, who have very different ideas on what should be done by Liu Shan. Poor guy needs a break.

He’s lost and confused, and just wants the fighting to stop. He’s so tired of Jiang Wei raging war and getting his ass kicked by Chen Tai (Among others, but Chen Tai needs to be playable) Wei/Jin. He’s tired of Huang Hao breathing down his neck about said wars. He’s tired of seeing everyone he loves die, no matter how many times he desperately tells them to rest (He does this a lot, knowing full well that exhaustion was what killed people like his father and Zhuge Liang.)

By the time Sima Zhao decides to storm in, Liu Shan is just a shell. He’s stressed beyond all belief, lost without his friends to advise him, and he just wants the chaos to end without raging war.

I think this is what makes Liu Shan so fantastic. Like Lu Su, he wants peace, and is willing to sacrifice victories for it. He doesn't see violence as the only means to peace (Considering Liu Bei preaches so much about benevolence, he does an awful lot of fighting) and is willing to sacrifice his own power and reputation if it means that the fighting will end. By surrendering to Sima Zhao, Liu Shan is losing everything. He knows he’ll be banished, he knows that nobody in Shu will ever respect him again. He knows this full well, and yet chooses to surrender, in the hope that peace will come soon.

His ending cutscene brought me to tears. Hearing the townsfolk shout insults and hurl rocks at Liu Shan’s carriage, calling him a failure, a mistake, despite him just wanting the best for everyone. And finding out that he’d been clenching his fists so hard he started bleeding in order to punish himself for causing this misery even though he was trying to end it... It hurt. And just that little ‘please’ at the end of his cutscene when he’s begging Zhang Xingcai to not help him... It was a downer.

He started off as a naive kid trying to live up to his father, and ended as a broken man.

Let him be happy dammit-

Interactions with other characters:

Liu Shan mainly interacts with Zhuge Liang, Jiang Wei, Zhao Yun, and Zhang Xingcai.

His relationship with Zhuge Liang is pretty professional. Liu Shan seems to genuinely care about him, constantly telling him to rest so as to not get sick from overworking. It wouldn’t be much of a stretch to say that Zhuge Liang was definitely Liu Shan’s teacher, and Liu Shan trusts him with all of his being (Maybe a little too much at times.)

Liu Shan and Jiang Wei have a very... strained relationship. It’s like they’re both desperately trying to get along but their ideas conflict so much that it doesn’t work. Nonetheless, Liu Shan is still kind and looking out for Jiang Wei’s health.

I like Zhao Yun. I love Liu Shan. And I love their interactions. Let’s face it, Zhao Yun is more of a father to Liu Shan than Liu Bei ever was. Zhao Yun is always praising his ‘son’, always there to support him and is continuously kind to him, and his death definitely impacts Liu Shan more than the death of Liu Bei.

The game doesn’t acknowledge Zhang Xingcai as Liu Shan’s wife, but they instead got his lovely evolving relationship, and I’m totally okay with that. She’s his emotional support, and while she’s not exactly any good at giving advice, she’s there as a friend and companion for him. She’s always there by his side, and he knows he can rely on her. He tells her everything, and it’s clear they both care for each other.

How this character could be improved:

That’s pretty subjective in Liu Shan’s case. By better, do you mean more likely to take initiative? Or perhaps back to his manipulative old self?

I like Liu Shan as a character the way he is, and I honestly don’t think he needs to be changed.

Except he should totally admit his feelings for Xingcai. And spend more time with his dad. No, I don’t mean Liu Bei, I mean Zhao Yun.

39 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Name: Li Mei Rong (李美容)

Onyomi: Ri Biyō | Style Name: Xiuhua

Affiliation:

Wei | Jin

Relations:

Li Dian & Airong (parents) | Li Jin (brother) | Xiaolian (auntie) | Yue Jin (favorite uncle) | Zhang Liao (uncle) | Wang Yuanji, Jia Chong, Sima Shi (friends) | Zhong Hui (rival)

Love Interest:

Sima Zhao | Zhang Chunhua (crush) | Zhong Hui

Weapon/Element:

Chan Zi Dao || Shadow

Personality:

Mei is not as easy to get along with, like her brother. She can be quite stubborn. She's pretty foul mouthed, especially when her lord or Zhang Chunhua have been insulted. She doesn’t care about labels and opinions casted over her. She also doesn’t care much for work, so she's usually lounging about. Can be a bit prideful.

Origins:

Mei was born a month after her father's death, so she never got to meet him. Despite that Mei, along with her brother, take after their father’s role, serving under the Cao family. Unfortunately Wei takes a turn for worse and Mei decides to follow under Sima Yi, seeing him to be the type of ruler she wished to serve. She takes part in most of Jin's battles against both Shu and Wu. She later marries Sima Zhao. However, due to her constant bickering with Zhong Hui, Mei gets conflicted about her feelings for both her husband and rival, and eventually commits suicide after Zhong Hui's death.

Current Role:

Like her brother, she now serves under the Sima clan in Jin. When she’s not on the field, she spends her time annoying Zhong Hui. Despite being his other wife, Meirong acts more of an armed maid in public, and a whole lot differently behind closed doors.

Fun Facts:

She only exists in an alternate story where Airong defects to Wei. She never got to see her mother's side of the family. She has the typical “Ojousama laugh.” She laughs like that on purpose to annoy Zhong Hui, and calls him a little boy. Doesn’t find it weird to have a crush on her lord's mother. In contrast to Yuanji, Meirong doesn’t nag her husband and lets him laze about whenever he wants.

Quote:

“That’s right, fall to your knees. Just like every other who dared to challenge me.”

_________________________________________

6 notes

·

View notes