#wickiup

Text

Canada’s National Indigenous Peoples Day

Learn about the various cultures and traditions of Canada’s Indigenous People, or join an event or ceremony to see how they have been preserved over time.

The culture, language and social systems of the original inhabitants of our world have had a significant impact on how we live our lives today. Canada’s National Indigenous Peoples Day is all about focusing on the contribution that these groups have made to our societies and helping people to learn about their heritage and culture. By celebrating this day, we can help keep Indigenous languages, traditions and culture alive for future generations.

Learn About Canada’s National Indigenous Peoples Day

The day officially first began in Canada in 1996, to celebrate the contributions and history of the Métis, Inuit and First Nation peoples. Since then, the day has been observed and celebrated internationally. Originally organized on the Summer Solstice (when the different peoples sometimes celebrate their heritage on the longest day of the year), the day’s events often include traditional feasts from each Indigenous People, festivals, dances, and the opportunity for people of all ages to learn about traditions, spiritual beliefs and culture. You might be lucky enough to see a sacred fire extinguishing ceremony or participate in a feast with a traditionally prepared meal.

It’s all about bringing people together from different walks of life to share in the contributions of Indigenous People to our society. You’ll find an eclectic mix of contemporary and traditional music while learning about how Indigenous Peoples helped to develop our agriculture, language and social customs. The day is also about how governments are creating crucial partnerships with Indigenous Peoples to protect their land, heritage and culture in modern times.

You can all get involved as the website has educational material for the whole family. There are also awareness events hosted in schools and local communities. If people want to get more involved they can even submit their ideas to get them registered as part of the event, so there are hundreds of opportunities to get involved. It also forms part of more extensive celebrations over an entire month that includes days like Multiculturalism Day and overall, aims to celebrate people from all walks of life and culture.

History of Canada’s National Indigenous Peoples Day

The day was officially recognized in Canada by the Governor-General of Canada Roméo LeBlanc in 1996. A year earlier in 1995, the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples put forward the idea for the day to be created. The Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples was a Commission put forward to reconcile the relationship between the Métis, Inuits and First Nation peoples and the Canadian Government. In 1996, Aboriginal Day was born, later changed to Canada’s National Indigenous Peoples Day in 2017.

In 1995, it wasn’t just the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples that suggested the day should be celebrated. A team of non-Indigenous and Indigenous peoples gathered and named themselves the Sacred Assembly. Chaired by Elijah Harper (Canadian Politician and Chief of the Red Sucker Lake First Nations) they called for a day for Indigenous Peoples to be celebrated and recognized for their contributions to our society. In 1982, what is now known as the Assembly of First Nations, set the path for the creation of this day, which led to Quebec recognizing the day as early as 1990.

However, there has been chatter about creating this day since 1945, when the day was first termed as ‘Indian Day’ by First Nation Chiefs, led by Jules Sioui. Jules Sioui was part of Huron Wendake First Nation and led two conventions during World War II which started to challenge the rights of Indigenous Peoples. The first meeting was chaired in 1943 in Ottawa and was attended by 53 people. The conference grew remarkably, and in 1944 was attended by four times as many people. Since then calls for a day of recognition have gained increasing traction and popularity.

Meanwhile, in late-1970s America, an International Conference began to suggest that America should host a celebration of its Indigenous peoples on Columbus Day. In 1989, it was first celebrated by South Dakota, and by 2019 was observed by multiple towns and states, including Louisiana, Dallas and Vermont. Brazil has also been celebrating since 1943, by decree of the then President, Getúlio Vargas. The UN also launched International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples in 1994, celebrating worldwide contributions from global Indigenous populations.

The United Nations had issued a Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) in 2007, which aimed to create a global framework for the preservation, dignity and well-being of each Indigenous culture. This process started in 1982, when the UN created the Working Group on Indigenous Populations, to discuss the discrimination that Indigenous Peoples had faced worldwide.

How To Celebrate Canada’s National Indigenous Peoples Day

This is the perfect time to learn about different Indigenous Peoples and their cultures and traditions. For example, in Canada, this day celebrates the First Nations, Inuit and Métis cultures. Why not learn about the Michif language of the Métis, or find out more about the storytelling traditions of the Inuits? Learning about the separate cultures will help us to understand how each independent group contributed to many of the things in society we take for granted today.

Why not get involved in a local event and participate in a traditional feast or watch a sacred ceremony? Dive right in and download some of the online material – why have some fun with family and friends and learn about Indigenous Peoples in the process? If you don’t have an event near you, why not host your own and reach out to the local Indigenous community for some assistance.

Learning about the history of Indigenous Peoples is also part of understanding why a day of celebration is so vital for preserving cultures today. From land disputes to reconciling with Governments across the world, the story for all Indigenous People has not been an easy one.

Luckily now we can preserve and enjoy all Indigenous cultures and appreciate the vast contribution that has been and is still being made today. So get stuck in, participate in a traditional event and learn all you can about different cultures. Help us send a big thank you to the original inhabitants of our planet for making it what it is today.

Source

#The Three Watchmen by James Hart#Gitwangak Battle Hill#Terrace#Whistler#Vancouver#Inukshuk by Alvin Kanak#Survivors of Whitehorse Indian Mission School by Ken Anderson#Finding Peace Monument by Halain De Repentigny#Whitehorse#Two Brothers Totem Pole by Jaalen and Gwaai Edenshaw#Jasper National Park#wickiup#Labyrinth Park#Grande Cache#Dorset Paleo Eskimo settlement#Inuit#travel#Lower Fort Garry National Historic Site of Canada#Canada’s National Indigenous Peoples Day#CanadasNationalIndigenousPeoplesDay#21 June#summer 2023#original photography#vacation#tourist attraction#First Nations

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Built-In Dallas

Large craftsman built-in desk in a home studio with a dark wood floor and beige walls.

0 notes

Photo

Home Office in Dallas

Large arts and crafts built-in desk dark wood floor home studio photo with beige walls

0 notes

Text

The Use of Wickiups and Tipis in Apache Culture

Image generated by the author

The Resilience of Apache Culture: The Significance of Wickiups and Tipis

As the sun dips below the horizon, casting a warm golden glow over the Southwestern landscape, the air fills with the aroma of sagebrush and woodsmoke. Families gather around a crackling fire, their laughter mingling with the soft rustle of the wind. This scene, steeped in tradition, is not merely a festive gathering; it is a vibrant reminder of the Apache people’s enduring connection to their land and culture. At the heart of these gatherings are two remarkable structures: the wickiup and the tipi. These dwellings, crafted from the natural materials of their environment, are much more than shelters. They embody the spirit, resilience, and adaptability of the Apache way of life.

Historical Context: A Nomadic Heritage

Imagine a time long ago, when the Apache people roamed the vast expanses of the Southwestern United States. Their existence was characterized by a profound relationship with the land, dictated by the rhythms of nature. As hunters and gatherers, they relied on their ability to adapt quickly, crafting shelters that matched their nomadic lifestyle. Wickiups, constructed from branches, grass, and dirt, served as temporary homes, allowing families to easily move as they followed game and seasonal resources.

Conversely, tipis, crafted from wooden poles and animal hides, represented the ingenuity of the Apache. These structures were not just functional; they were designed with an understanding of the environment that surrounded them. The conical shape of the tipi facilitated warmth during the bitter cold of winter, while its circular design promoted airflow, keeping the interior cool during the sweltering summer months. Both the wickiup and the tipi were integral to Apache life, serving practical purposes while also hosting cultural and spiritual rituals that reinforced community ties.

Cultural Significance: A Reflection of Identity

Beyond their physical forms, wickiups and tipis are symbols of Apache identity. They reflect core values that resonate deeply within the Apache ethos: harmony with nature, adaptability, and community. The very act of gathering within these structures fosters a sense of belonging and continuity, as stories are shared and traditions are passed down through generations.

Picture the spacious interior of a tipi, where families come together, seated in a circle around the fire. The flames flicker, casting dancing shadows on the hide walls, as an elder recounts tales of bravery and wisdom. This is not just storytelling; it is a vital educational process, where the youth learn about their heritage and the lessons embedded in their ancestors’ experiences. The construction of these dwellings itself teaches respect for the land and the importance of living sustainably. Each pole, each branch used in their creation, carries with it the spirit of the environment, reminding the Apache of their responsibility to protect and honor their surroundings.

An Apache Story: Lessons from Elders

One particularly poignant story comes from Shasta, a revered elder in the Apache community. He recalls his childhood, filled with warmth and laughter within the walls of a wickiup. “These structures,” he explains, “are not just homes; they are a testament to our resilience.” Shasta describes how each season brought with it a new adventure, as his family would dismantle the wickiup and relocate in search of food and resources. This mobility, he emphasizes, is what has sustained the Apache people for centuries.

Through Shasta’s eyes, we see the wickiup not merely as a shelter but as a vessel of survival, unity, and respect for nature. Each gathering around the fire was a chance to reinforce family bonds, share knowledge, and weave the fabric of their community tighter. The wisdom that resides within these stories offers invaluable lessons about adaptability and the importance of living in synchronization with nature.

Construction Techniques: A Legacy of Ingenuity

The construction of wickiups and tipis exemplifies the Apache's understanding of their environment. Wickiups, often temporary structures, are ingeniously designed to be easily assembled and disassembled, allowing for mobility in a nomadic lifestyle. Their walls, made from locally sourced materials, provide shelter from the elements, while their design promotes warmth in winter and ventilation in summer.

On the other hand, the tipi, while often associated with Plains tribes, also holds significance for various Apache groups. Its design is not just about form; it is a deep-seated understanding of how to utilize the environment effectively. The use of animal hides not only provides insulation but also allows for a connection to the animal world—a reminder of the Apache’s respect for all living beings. Cultural anthropologists and historians emphasize that these structures are not just remnants of the past; they are a testament to the Apache's adaptability and innovative spirit.

Practical Applications: Sustainability in Action

As we look at the world today, the principles embodied in the construction of wickiups and tipis offer practical lessons for modern living. In an era marked by environmental crises and a disconnection from nature, the Apache way of life provides a blueprint for sustainable practices. The circular design of tipis encourages energy efficiency; it utilizes natural heating and cooling methods, thereby minimizing reliance on modern energy sources.

Moreover, the use of local materials showcases an understanding of resourcefulness that is increasingly relevant in our society. By embracing these ancient techniques, we can foster a greater connection to our surroundings and build communities that prioritize sustainability. The Apache teachings remind us of the value of living in harmony with nature, a lesson that can no longer be overlooked in the face of climate change.

Modern Relevance: A Call to Action

In a world that often seems disconnected from its roots, the traditional structures of the Apache serve as symbols of resilience and harmony with nature. Rising environmental concerns and the quest for sustainable living have sparked renewed interest in these ancient methods of shelter. The Apache way of life encourages us to reflect on our relationship with the earth and consider how we can incorporate communal spaces into modern designs, fostering connections reminiscent of their culture.

As we navigate the complexities of contemporary living, we would do well to draw inspiration from the wisdom of the Apache. Their adaptability and deep understanding of the environment can guide us in facing the challenges posed by climate change and environmental degradation. Imagine urban centers that incorporate communal gathering spaces, where storytelling and cultural education thrive, echoing the traditions held within Apache dwellings.

Conclusion: A Legacy Worth Honoring

As the fire dwindles and the stars blanket the night sky, the Apache wickiup and tipi stand as enduring symbols of resilience, adaptability, and a profound understanding of the environment. They are not mere structures; they are reflections of Apache identity and values, carrying forward teachings about sustainability and community that are urgently needed in today’s world.

In honoring the legacies of these traditional shelters, we must also acknowledge the importance of integrating this wisdom into our contemporary lives. The Apache people remind us of the delicate balance we must maintain with nature and the strength found in community. So, as you ponder the legacy of these remarkable structures, ask yourself: How can we adapt these lessons to foster a more sustainable and connected world? The answer may lie in the very wisdom that has guided the Apache people for generations, waiting to be rediscovered and embraced anew.

About Black Hawk Visions

Black Hawk Visions preserves and shares timeless Apache wisdom through digital media. Inspired by Tahoma Whispering Wind, we offer eBooks, online courses, and newsletters that blend traditional knowledge with modern learning. Explore nature connection, survival skills, and inner growth at Black Hawk Visions.

AI Disclosure: AI was used for content ideation, spelling and grammar checks, and some modification of this article.

About Black Hawk Visions: We preserve and share timeless Apache wisdom through digital media. Explore nature connection, survival skills, and inner growth at Black Hawk Visions.

0 notes

Text

Wickiup, OR. 06/01/2024.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Native American Outdoors Wickiup Mother And Child Apache 1900

Apache woman carrying child on her back - ca 1900 ...

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Made the U.S. History kids go outside and build wickiups today as a part of our Native American tribes unit

0 notes

Video

Any Excuse to Visit Mesa Verde National Park by Mark Stevens

Via Flickr:

While hiking the Petroglyph Point Trail with a view looking to the northwest while taking in the setting with the canyons and cliff walls present in this part of Mesa Verde National Park. My thought on composing this image was to pull back on the focal length and capture a wide-angle feel, while angling my Nikon SLR camera slightly downward to bring up the horizon higher into the image. That I felt would help create more of a sense of grandeur in the canyons (Spruce Canyon and Wickiup Canyon) and cliff walls

#Ancestral Puebloan#Ancestral Puebloan Archaeological Sites#Archaeological Preserve#Archaeological Sites#Azimuth 308#Blue Skies#Blues Skies with Clouds#Cliff#Cliff Walls#Cloudy#Colorado Plateau#Day 5#DxO PhotoLab 7 Edited#Evergreen Trees#Evergreens#Forest#Forest Landscape#Hillside of Trees#Intermountain West#Landscape#Landscape - Scenery#Looking NW#Mesa Verde National Park#Mostly Cloudy#Nature#New Mexico and Mesa Verde National Park#Nikon D850#No People#Outside#Overcast

0 notes

Text

Three Sisters and Broken Top Circumnavigation (4/5)

On this five-day trip filled with highs and lows (but mostly highs), the fourth day, spent hiking from Reese Lake to Green Lakes, was probably the most straightforward day. That doesn't mean it wasn't still awesome, though.

Hoping to get to Green Lakes early enough in the afternoon to enjoy it before the sun set, I got up before sunrise and was on the road shortly after it.

Less than a mile south of Reese Lake, I passed into the burn zone from the 2017 Nash Fire. Though the first few miles of hiking for the day were relatively flat as the PCT traversed around the west flank of South Sister, my environs more closely resembled the blasted east side of the Sisters Loop than what I'd grown used to on the less-burnt west side.

While there wasn't a lot of elevation change through this section, there were parts where the soil was so loose due to the burn that it was hard to simultaneously scramble up and over deadfall and avoid turning an ankle in the loam.

At one point, I passed a family of four, all of them ahorse and kitted out as if they had literally walked out of an episode of Yellowstone. The father, riding in the lead, literally tipped his cowboy hat to me when I said hello. All four riders had long rifles low-slung from their saddles, and rifle bullets displayed prominently (and individually) in pockets sewn onto their saddles. A blue heeler wove in and out of the horses' legs as they passed by. I felt like I had traveled back in time.

Shortly after, I passed a small lake that could have provided a camp site and overnight access to water in an emergency. It had nothing on Reese Lake, though.

Next up was Mesa Creek, where the man I'd met the previous morning at the Yapoah Crater had recommended I camp. While seeing it in the flesh didn't make me regret my choice of Reese Lake, the open meadow through which the creek ran was gorgeous and golden in the fall light. There were plenty of open campsites under the trees that lined the meadow, and the creek itself was running fast despite the lateness of the year. I dropped a pin on my map so I would remember the spot for any later trips.

Not far beyond the meadow the trail climbed up through some trees to a spot that Lindsey, who is partial to alpine meadows, had dubbed "The Ultimate Place" on our 2018 hike. I dropped a pin on the map here as well, and took some pictures so she could at least feel like she'd been there in spirit this time around.

It wasn't long after this that the trail squeezed between a bluff to the right and the creatively-named Rock Mesa to the left, a pass-through that served as the gateway to the Wickiup Plain.

There are a lot of spots along this loop that you could mistake for Mordor, or the moon, but none are more strikingly desolate than the Wickiup Plain. This had been another spot where we'd struggled in 2018: the PCT only runs for about one-and-a-half miles through the Plain, but it's entirely open, and there's just something about being able to see so far into the distance that's dispiriting when you're trying to cover distance while avoiding melting in the sun.

All that said, the Rock Mesa rising to your left in front of a snowy South Sister summit is quite the sight.

Crossing the Plain this time around was significantly less apocalyptic than in my memory, likely because of the fall temperatures. Before long, I bore left onto the Le Conte Crater Trail, leaving the PCT and its relatively heavy (read: "not heavy at all") traffic flow behind for the rest of the trip. The sharp cone of the Le Conte Crater passed by on my left, and then Kahleetan Butte appeared in the distance: a pretty unremarkable butte made remarkable by the flatness of the surrounding area.

The Le Conte Crater Trail proceeds for a mile through this open area before it ends in a T-intersection. I turned left/north and began to climb - a rarity on this particular day!

The Moraine Lake Trail climbs about five hundred feet en route to the eponymous Moraine Lake, but on this morning, when I'd already gotten into my head the idea that this was supposed to be an "easy" day, the climbing felt like a struggle. At least while contouring around Kahleetan Butte I got to hike through the thick pine forest that's typical just south of South Sister. The shade kept me cool as I climbed a trail that seemed far steeper than I remembered.

Eventually, though, the "classic" view of South Sister appeared as I crested a hill. Two days before, I'd reached South Matthieu Lake and a dead-on view of North Sister from the north. Now, at the other end of the loop, the south side of South Sister loomed. I wasn't done yet, but it felt like a milestone along the way.

The reason I think of this as the "classic" view of South Sister is because I and many others experience the mountain primarily through climbing it, and the vast majority of those attempting to summit do so from the south, from the Devil's Lake Trailhead. After an initial climb from that trailhead, you reach a plateau due south of the mountain where the climber's trail and the Moraine Lake Trail cross. I've been to this intersection many times, typically in pursuit of the summit, and I was looking forward to reaching it again on this trip, even if I was approaching it from the west instead of the south, and even if I was "just" passing through rather than summiting the mountain.

Upon arrival at the plateau intersection, I stopped briefly, reflecting on all of the times I'd passed the spot before. This had been Lindsey and I's last break spot in 2018 before we'd completed the Sisters Loop by descending the final mile-plus to Devil's Lake. It was a place heavy with memories shared with others on a trip where I had spent most of a week living in my own head. It was a nice reprieve.

From the plateau, I descended northeast and down to Moraine Lake, then took a long lunch break on the shore. Moraine Lake is a spot I've often seen and appreciated from a distance, so I was happy to have the opportunity to spend some quality time there.

From Moraine Lake, I turned east and eventually south to skirt around the awesomely-named Devil's Chain, a long, tall lava formation that oozes down to the southeast of South Sister proper. This section of the trail always takes longer than it seems like it should, but once you've made it around the formation and you loop back toward the north, you enter one of my favorite sections of trail in the entire Sisters Wilderness.

Here, for about two miles, you hike alongside both lava walls and Fall Creek, sheltered by tall pines and ensconced in the sound of rushing water. Especially after three-ish days of mostly dry landscapes punctuated by burn zones, this area, which I suppose is still apocalyptic by most standards, felt absolutely paradisaical.

By this point, I was also well into popular day-hike territory. I felt a bit self-conscious about my relative grubbiness as I passed and was passed by lots of fashionable and clean Bend-area day-hikers, but I also figured they were used to occasionally having a hairy backpacker crash through the background of their Instagram Reels.

Eventually, I reached the outskirts of the Green Lakes area, which is one of my all-time favorite places to camp. Earlier in the day, I'd been a bit worried about finding a good campsite here; this was mostly because before 2021, Green Lakes had been one of the best-known and best-"loved" backcountry spots in Oregon, and accordingly, one of the most difficult places to find a campsite at on any given (summer) night. In 2021, though, the Forest Service began a new permit system that limited access to the area, and since then, it's never been the absolute circus it once was, at least not on the days that I've been there. My worry that all the sites in the area would be full up in spite of the permit system, in the middle of October, was irrational, of course. I didn't expect to find the entire place to be empty save for two other hiking parties, though!

My favorite sites in the Green Lakes area are all on the southern side, so last summer, when I entered the area from the north on my way around Broken Top for the first time, I took the time to hike all the way around the Lakes before settling in for the night. This time, I was approaching from the south, which meant that I didn't have to hike around the Lakes at all to reach my favorite spots. It also meant that I'd have much more time to just enjoy the views and rest before having to get set up for my last night of camping out on this trip.

One of the many things I love about Green Lakes is that you can see all Three Sisters and Broken Top from certain spots along the main lake. This makes for some beautiful views, of course, but as someone who was currently undertaking a circumnavigation of all four peaks, the encompassing view had special resonance.

I'd entered the area hoping to get one of my favorite three sites for the night. As it turned out, nobody else was camping anywhere near the south end of the Lakes at all. So, instead, my "problem" became choosing while of the three great sites I wanted to set up at. Ultimately, I chose the same site I'd camped at the previous year during my first loop around Broken Top, which provides excellent views of both South Sister and Broken Top from your tent.

With some extra daylight on my hands after setting up my tent, I took a short sojourn out around some of the Lakes sans my backpack, took some (more) photos, chatted with one group of campers, ate a few cookies, and then returned to my site just as dusk was settling in.

After cooking one last dinner, I decided to put off going to bed for a bit and instead walk down to the south shore of the closest lake and sit for a bit. I did have a long, difficult day ahead of me the next morning, but it would be the last of the trip, and I felt well-rested and well-fed enough that I wasn't terribly worried. If I slept poorly or didn't get enough sleep, at this point I could just power through it. Veggie burgers and a real bed were only twenty-four hours away, after all.

For the first time in all my visits to Green Lakes, I had the time to take some astrophotos of one of my favorite views on Earth, looking across the water toward South Sister.

Then, I walked back to my tent and went to bed for the night, both looking forward to and dreading finishing this fantastic trip with a visit to the incredible Bend Glacier and scrambling the long-awaited pass over Broken Hand.

#mountains#central oregon#north sister#middle sister#south sister#hiking#camping#backpacking#photos#three sisters#writing#broken top

1 note

·

View note

Text

CCC Camp Wickiup Initiated Development of Wickiup Dam

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

the contestants are all putting so much i energy into their shelters except one guy who was like. well i need to make sure i know i have a good source of food before i make a more permanent shelter. and guess who is doing the best. him! like these other people are barely eating and are putting SO much work into building a structure while he just now day 22 was like. i guess i’ll just make myself a little wickiup (<-i just learned what this is it is similar to a wigwam) inspired structure (very much inspired it is so much not a proper wickiup) i have a feeling he’ll win but tides could change. the guy that sounds like my grandpa killed a beaver and the guy w the cool house has a pretty good supply of squirrels and fish and grouse. but i like benji the most rn in terms of survival.

0 notes

Text

Grande Cache, AB (No. 4)

Grande Cache is located in the northern part of the Rocky Mountains, in western Alberta, along Highway 40, also known as the Bighorn Highway or Scenic Route to Alaska. This is the shortest and most scenic route to Alaska from the United States.

Escape into a land of sparkling lakes, rushing rivers, green valleys, and windswept peaks! Grande Cache is surrounded by panoramic views of 21 mountain peaks and 2 river valleys. Grande Cache is located 183 km south of Grande Prairie and 143 km north of Hinton. Jasper is 210 km south of Grande Cache and Edmonton is 450 km east of Grande Cache. This small mountain hamlet is adjacent to unspoiled Willmore Wilderness Park. Willmore Wilderness Park has an abundance of trails, big game, alpine flowers and spectacular waterways. Grande Cache has an excellent choice of shops, campgrounds, accommodations, restaurants and endless multi-use trails.

There is something for everyone; photographers, artists, golfers, rafters, kayakers, hikers, bikers, paddlers, horseback riders, cross-country skiers, fishermen and hunters alike. Through its unique activities, like running the Canadian Death Race on the August long weekend, hiking the Passport to the Peaks program, walking the Labyrinth Park or backpacking in Willmore Wilderness Park, Grande Cache offers outstanding outdoor adventure and a relaxed lifestyle.

Source

#First Nations#Native American#Grande Cache Tourism & Interpretive Centre#Grande Cache#Alberta#Municipal District of Greenview No. 16#Upper Peace#Rocky Mountains#Northern Rockies#Alberta's Rockies#travel#original photography#vacation#tourist attraction#landmark#cityscape#landscape#summer 2023#Canada#small town#Bird’s Eye View Interpretive Park#Wickiup#architecture#log cabin#Labyrinth Park

0 notes

Text

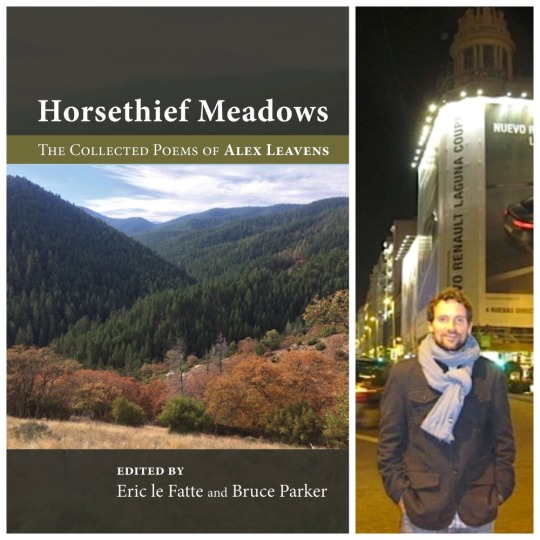

NEW FROM FINISHING LINE PRESS: HORSETHIEF MEADOWS: The Collected Poems of Alex Leavens

On SALE now! Pre-order Price Guarantee: https://www.finishinglinepress.com/product/horsethief-meadows-the-collected-poems-of-alex-leavens/

ONE LAST WORD PROGRAM

Alex Alan Leavens, was born on July 30, 1975 and raised in Portland, Oregon, as a fourth- generation Oregonian, whose great-grandfather arrived in 1895. He developed his interest in the outdoors as a child, and attended Prescott College in Arizona, where he lived for a year in a wickiup he designed and built. He also attended the Boulder Outdoor Survival School, which led him to start two businesses: the Old Federal Ax Company and the Oregon School of Survival and Tracking. He taught skills ranging from making primitive pottery of the Anasazi tradition to animal track identification. He also served as a firefighter in Arizona, southern California, and the Olympic National Park.

Alex later received a Bachelors degree in English Literature at Portland State University, where he graduated summa cum laude. He honed his craftsmanship skills at properties he and his family owned in Portland, volunteered at the Portland Museum of Art, became an expert baker and charcuterist, and hunted and fished throughout the Oregon backcountry. He also began writing–first a novel, The Border, and then poems infused with his devotion to craftsmanship, art, and a unique perspective on nature. In just a few years, Alex published numerous poems in literary magazines, including Cathexis Northwest, Cirque, Clover, The Ekphrastic Review, Frogpond, Modern Haiku, Montana Mouthful, Tiny Seed Literary Journal, Perceptions Magazine, Wild Roof Journal, and Windfall. Sadly, as his career as a poet began to flourish, Alex Leavens died by suicide on August 13, 2021. The poems he left behind are gathered here. –Eric le Fatte

PRAISE FOR HORSETHIEF MEADOWS: The Collected Poems of Alex Leavens

As with John Haines, Alaska’s poet of the wild, or Gary Snyder, Alex Leavens is a poet of deep #ecology. His posthumous collection, Horsethief Meadows, brings poems of reverence, wisdom and precision in observation of the natural world, as with these lines: “…the mountain lion had the same tint as the moon ….” With felt grief as wildfires burn out of control, Leavens observes that “flames climb into treetops to ferry substances, no longer bound to earth…”

–Sandra L. Kleven, publisher/editor, CIRQUE: A Literary Journal, and Cirque Press

In the work of the late Alex Leavens, the reader finds compelling poetry of place with a poet who serves as guide and teacher to the backcountry Pacific Northwest. But also found in his poems is a student of witness: we experience the “behaviors and talents of the cold,” see tracks of bears “that won’t heal over,” admire a “thin, wet brush” of a mink at “that lake nobody knows.” With maturity and métier, Alex held a steady gaze over difficult landscapes of harsh seasons, centuries of human intervention, and increasingly, traumatically, fire.

–John Miller, author of Olympic

The poems in Alex Leavens’ collection, Horsethief Meadows, measure the human against the “circumference of the world.” Leavens’ narrator is a shapeshifter moving through that world, helping us to remember we are all one: “and the wind/ found its way down/ into the dry mouth of the badger’s sett,/ down into the earth/ to remind the grove/ to stay joined/ at the root,/ to speak as one living thing.” In poetry “equal to the horizon,/ equal to the morning sun,” Leavens puts us there at the center of things—circling with the hawk overhead, wandering with the cougar down through a streambed, or sunning our wings with the butterfly. A lyric work of interconnectedness between the human and the natural worlds, Leavens’ poems burn like a fire, showing us the way in “that small matter/ of living/ at the center/ of the dark.”

–Peter Grandbois, author of Last Night I Aged a Hundred Years

Please share/repost #flpauthor #preorder #AwesomeCoverArt #read #poems #literature #poetry

1 note

·

View note

Text

Verkenners Scouting Boxtel organiseren succesvol restaurant

Afgelopen zaterdag 28 februari was het een drukte van jewelste bij Scouting Boxtel, waar de verkenners vrijdag hun eigen restaurant organiseerden om geld in te zamelen voor hun zomerkamp. De gasten konden die avond genieten van een heerlijke maaltijd en een avondvullend programma.

De jongens van 11 tot en met 15 jaar organiseren ieder jaar een restaurant in een bepaald thema. Tijdens de avond vervullen de verkenners de functies van ober, afwasser, barman, keukenhulp en entertainer. Dit jaar was het thema van het restaurant: Nederland. Hier waren de gerechten, aankleding en het entertainment op afgestemd.

De 77 gasten, veelal ouders en andere familieleden, werden hartelijk ontvangen bij blokhut De Wickiup, waar ze genoten van een lekkere maaltijd terwijl ze bijdroegen aan een goed doel. Het geld dat de verkenners verdienden zal worden gebruikt voor een leuke extra activiteit tijdens hun zomerkamp.

Als voorgerecht kon er een keuze gemaakt worden uit groentesoep of erwtensoep. Hierna volgde het hoofdgerecht: hachee met aardappelpuree en rode kool, of een ‘stampoentje’ van pompoen en knolselderij met grootmoeders gehaktbal. Om af te sluiten een bolletje vanille ijs met chocoladesaus of een heerlijk stroopwafelparfait. Tussen de gangen door werden er verschillende acts opgevoerd ter vermaak van de gasten.

Een van de gasten was erg enthousiast over de georganiseerde avond: “Ik ben onder de indruk van de professionele houding van de verkenners. Ze zijn erg gastvrij en doen alles met veel plezier. Het eten smaakte heerlijk en ik ben blij dat ik ook wat heb kunnen bijdragen aan hun zomerkamp.”

Scouting Boxtel

Scouting Boxtel is dé Scoutinggroep voor Boxtel, Liempde, Esch, Gemonde en Lennisheuvel. Scouting Boxtel heeft uitdagende programma's voor kinderen van 5 t/m 18 jaar en ook voor scouts met een beperking. Iedere leeftijdsgroep heeft programma's afgestemd op de kinderen in de groep. De diversiteit in het programma betekent dat geen opkomst hetzelfde is. Alle leeftijdsgroepen sluiten het jaar af met een zomerkamp. Dit aangevuld met diverse weekendactiviteiten maakt Scouting tot een veelzijdige hobby.

Bron: Scouting Boxtel

0 notes

Text

The Use of Wickiups and Tipis in Apache Culture

Image generated by the author

Shelters of Resilience: The Cultural Significance of Wickiups and Tipis in Apache Life

Imagine a scene painted with the glow of a crackling fire, surrounded by the silhouettes of towering mountains under a starlit sky. The warmth radiates not just from the flames, but from the laughter and stories shared among family and friends gathered within the comforting embrace of a wickiup. This is not merely a structure; it is a cradle of culture, a testament to the enduring spirit of the Apache people. As we delve into the world of these traditional dwellings, we uncover not only their practical roles but their profound cultural significance that resonates through generations.

Apache Family Gatherings: More Than Just Shelters

At first glance, one might see the wickiup and the tipi as mere shelters against the elements. However, they are much more—they are living embodiments of Apache identity. Constructed from natural materials, these dwellings symbolize the Apache’s intricate relationship with their environment. The wickiup, built from branches, grass, and dirt, is a structure that allows mobility, while the conical tipi, adorned with animal hides, stands tall against fierce winds and snow. Together, they create spaces of comfort and community, where family ties are forged and stories are passed down like precious heirlooms.

Picture a chilly evening in the heart of the Apache territory. Families gather around the fire, the flickering light illuminating the faces of elders and children alike. The aroma of roasting meat fills the air, mingling with the scent of cedar smoke. It is within these walls that the fabric of Apache culture is woven—where teachings of respect, survival, and unity echo through time. Here, storytelling takes center stage, as elders share tales rich with wisdom, teaching younger generations about their heritage and the delicate balance of life within nature.

Historical Context: Dwellings that Adapt

The Apache people have navigated the rugged landscapes of the Southwestern United States for centuries, their lives deeply intertwined with the rhythms of nature. Their nomadic lifestyle necessitated a design that was both practical and adaptable. Wickiups and tipis are perfect illustrations of this ingenuity.

Wickiups, with their low-profile design, are easily constructed and dismantled, allowing families to follow game and seasonal vegetation. Meanwhile, tipis, characterized by their sturdy wooden poles and animal hides, provide warmth and shelter during harsh winters. The very structure of these dwellings reflects the Apache's resourcefulness, their ability to adapt to varying climates, and their profound respect for the land that sustains them.

These homes also serve as cultural hubs. They are venues for rituals, storytelling, and communal gatherings, safeguarding the Apache way of life. Each structure is a canvas painted with history, spirituality, and the teachings of ancestors, carrying the weight of their wisdom into the future.

Cultural Significance: The Spirit of the Apache

Within the Apache community, wickiups and tipis are not just physical structures; they are symbols of resilience and adaptability. The symbolism is woven into the very fabric of these homes. The conical form of the tipi, for example, is a marvel of design—its shape effectively sheds snow and withstands powerful winds, much like the Apache people who have thrived against the odds.

Within these walls, the spirit of the Apache is alive. Shasta, an elder, sits with the youth around a fire, sharing tales that breathe life into the past. He speaks of the wickiup’s mobility, a reminder that adaptability is key to survival. With each flicker of the flames, he recounts how, like the wickiup, the Apache people have moved and evolved over time, always honoring their connection to the earth.

Conversely, he highlights the warmth of the tipi—a sanctuary during the coldest months. “These structures,” he says, “are not just homes; they are our teachers.” They carry lessons of unity and respect for nature, reminding the younger generation of their place within the larger web of life.

Modern Relevance: Lessons for Today

In an era where sustainability and community bonds are increasingly vital, the principles embodied in Apache dwellings resonate loudly. The construction techniques of wickiups and tipis reveal a deep understanding of natural resources and climate adaptation. Their designs utilize local elements for heating and cooling, showcasing a blueprint for modern sustainable living that emphasizes harmony with the environment.

Architects and urban planners today can glean invaluable insights from these traditional structures. The communal nature of wickiups and tipis fosters social connections, suggesting that modern architecture could benefit from integrating shared spaces that encourage fellowship and cultural exchange. Imagine urban designs that echo the Apache philosophy—a blend of sustainability and community that nurtures both the environment and the people.

Moreover, the wisdom embedded in these structures is a reminder of our responsibility to the planet. As climate change looms, the Apache way of life offers a path forward, one rooted in respect for nature and the interconnectedness of all living things.

Conclusion: Honoring Heritage and Wisdom

As we reflect on the significance of wickiups and tipis, it becomes clear that these structures are far more than mere shelters; they are profound symbols of resilience, adaptability, and cultural identity. The Apache people constructed these homes as reflections of their values and their deep understanding of the land.

In a world increasingly disconnected from nature, the teachings of the Apache resonate louder than ever. They remind us of the importance of community, the necessity of sustainability, and the wisdom that lies in honoring our roots. As we gather around our own fires, let us remember the enduring spirit of the Apache and strive to integrate their lessons into our lives—embracing the interconnectedness of all beings, and forging a future that respects the delicate balance of our shared home.

In this way, the legacy of the Apache lives on, inviting us to learn, adapt, and grow, just as they have for generations. So, the next time you find yourself around a fire, whether in a wickiup, a tipi, or your own home, take a moment to reflect on the stories that brought you there, and the wisdom that continues to guide you.

About Black Hawk Visions

Black Hawk Visions preserves and shares timeless Apache wisdom through digital media. Inspired by Tahoma Whispering Wind, we offer eBooks, online courses, and newsletters that blend traditional knowledge with modern learning. Explore nature connection, survival skills, and inner growth at Black Hawk Visions.

AI Disclosure: AI was used for content ideation, spelling and grammar checks, and some modification of this article.

About Black Hawk Visions: We preserve and share timeless Apache wisdom through digital media. Explore nature connection, survival skills, and inner growth at Black Hawk Visions.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wickiup, OR. 06/02/2024.

19 notes

·

View notes