Text

youtube

#film#movies#mr. smith goes to washington#mr. smith goes to washington 1939#1939#30s#political#drama#comedy#james stewart#jean arthur#claude rains#edward arnold#frank capra#Youtube

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

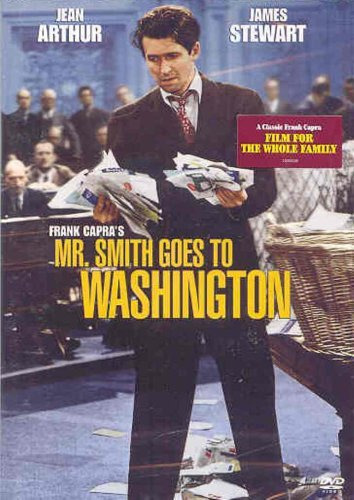

Mr. Smith Goes to Washington: Genre and Themes

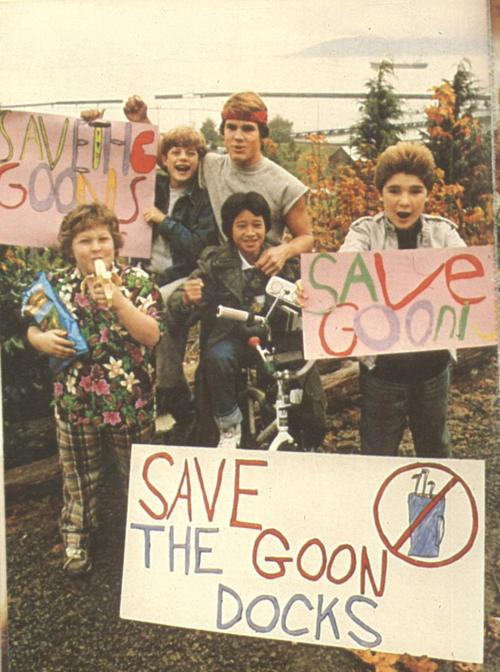

At first glance, indeed, even at second glance, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington doesn’t seem to really lend itself to a specific genre the way The Goonies or The Princess Bride did. Whereas those films positively dripped with the atmosphere of an adventure or fantasy film, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington is considerably more ‘real world’ than that, without necessarily heading into ‘slice of life’ territory.

If story is the backbone of a film, the underlying solid base, then genre is the trappings, the flavor, the seasonings the writers get to play with to create their final dish. Some stories automatically come with pre-packaged genre, as it would seem, stories like Frankenstein seem little suited to be anything other than a sci-fi horror film, after all, but most, and indeed some would say all stories have the capabilities of remaining solid in their identities, even with a completely different genre than we’re used to.

In the case of Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, however, there doesn’t seem like there’s a lot of ingredients to mix.

Officially, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington is labeled as a ‘political comedy-drama’, an eclectic mishmash of styles that doesn’t necessarily rear its head too often in the realm of film. Political films tend to be more true stories like All the President’s Men, or thrillers like The Manchurian Candidate. Mr. Smith Goes to Washington is neither. However, that isn’t to say it’s not political.

The entire world of Mr. Smith Goes to Washington is politics. It lives and breathes the inner workings of American bureaucracy, without either exploiting or sugarcoating it.

It is, at its core, an anti-politics political film. There is no pleasure that the film derives from exposing any corruption, nor does it take pains to pretend that corruption does not exist. It freely paints the politicians and the non-politicians as people, dealing with consequences to their actions: from Senator Paine, the tarnished hero, to Clarissa Saunders, the cynical, worn-out tool of Washington. The focus of the story is not so much on the inner workings of the state and country as it is the people that perform them, that manipulate the cogs of the machine to their own benefit, and those who stand to prevent it.

It’s not a very technical film. You don’t have to have a degree in law in order to understand the film, or allow it to resonate, and that, perhaps, is what makes it so special.

The ‘political’ slant of Mr. Smith Goes to Washington isn’t in the process that Saunders outlines to Jefferson in order to get his bill passed. On the contrary, the bill itself is a minor incident, the catalyst that forces the corruption out into the open. The story isn’t about the bill at all, nor is it even about the plot of the other politicians: it is about the politicians themselves. There are no parties mentioned, no real figures portrayed, no accurate historical events referenced: and yet something about this film did strike a chord in the very real Washington D.C.

Upon Mr. Smith’s release in Constitution Hall, DC dissolved into uproar about the film’s portrayal of American politics, to the point that Alben W. Barkley, the Senate Majority Leader at the time, remarked that it: “makes the Senate look like a bunch of crooks”.

In other words, something about this film struck some people, mostly the people in Washington, the wrong way. And yet, even at the time of its initial release, audiences, the Mr. Smiths of the USA, adored it for a reason.

At its core, chiefly, yes, Mr. Smith is a film about politics, and even history. Every fiber of the movie vibrates with patriotism, with love for America, and with pride in democracy. The film is not a condemnation as such as it is a warning: ‘we will lose what we have built if we think only of ourselves.’ It is a perfect combination of both a celebration of America’s past, and a concern for the future, a notation of the path the nation’s leaders seemed to be going down. Mr. Smith Goes to Washington is a story about big P Politics, all right, but it is not a scowling, scolding film, pointing an accusatory finger at the little p politicians, the fallen white knights. It is instead a film that holds up a figure of a person who knows on what the country was founded, and believes in it so strongly enough that he forces a change, even if it’s a small one.

And the film is also pretty funny, too.

The genre of ‘comedy’ tends to bring to mind slapstick or wordplay classics, and in the 1930s, the ‘comedians’ definitely had their specific brands: the Marx Brothers, the Three Stooges, Laurel and Hardy, and others were taking cinema by storm. Audiences, especially in the middle of the Great Depression, desperately wanted a laugh, and even though there were no pratfalls in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, there is a wry sense of humor about it, particularly near the beginning.

Early scenes in this film play almost like scenes from a ‘fish out of water’ comedy, with Jefferson Smith having no idea how to function in the new, fast-moving, cynical climate of Washington D.C. Other characters, such as Saunders and Diz, exist as quip-generating machines, full of the fast-paced, witty dialogue characteristic of films of the time. Many of the more comedic sequences in the story come about through direct conversation between Saunders and Smith and the subsequent clash of ideas and personalities.

So yeah, Mr. Smith is a pretty funny movie at times. I must admit though, it’s hard to make the argument that it’s a comedy.

Smith’s plight is not comedic, at least, not more than halfway through the story. He is not a comedic figure, nor are most of the characters around him. While one could make the argument that the initial conceit of the story is comedic, I am hard pressed to agree that the story remains a comedy throughout. If anything, the throughline of tragedy seems clearer, notably in the character of Senator Paine.

Paine is what Smith could have been: a noble figure broken by greed, by corruption, by fear, turned into another cog in someone else’s profit machine, willing to throw countless people under the bus for gain. By the end of the story, he is not only guilty, he is convicted, ashamed after being forced to confront what he has become. His story nearly ends in suicide, and it certainly ends in the ruination of his career, after having thrown away belief in all of the words he is so used to spouting. He is the warning thrust up before contemporary Washington’s eyes: the white knight tarnished by greed.

Smith’s story, though uncorrupted, is similarly bleak: unbelieved, unheard, and unable to get the word out, he ends the film exhausted and crushed after hours of seeming futility. The film’s happy ending does not come as a result of all of his hard work, but through the guilt of Senator Paine driving him to confess. Smith does not reach the climax of the film like a comedy protagonist does at all, but like a tragic hero.

And yet, this film isn’t a tragedy either.

So what is it?

I have a theory: that a film’s genre can be best solidified through a few major checkpoints: its themes, and its characters, specifically its protagonist.

The themes of Mr. Smith are obvious ones: duty to one’s country, certainly, but honesty above all. The liars are the villains, and the heroes tell the truth. The story is built around good morals and simplicity, with the center of virtue being Mr. Smith himself.

In another era, Smith himself may have been a knight in shining armor, risen to his position from peasantry to achieve noble deeds. As it is, in 1930s America, Smith is an ordinary man in an extraordinary position: an everyday guy elevated to the position of senator.

Of course, the intention was never to give him any real power, but nonetheless, power he wields. And it’s his decisions on handling that power that set him apart from the other characters. He behaves very much like a normal person, an average citizen in a political jungle with very little navigation. There is no hero’s journey here: if anything, Mr. Smith finishes the story as a broken, more cynical character rather than a triumphant hero. The victory is in refusing to compromise your principles, no matter the cost or circumstance, and there is no dragon to slay here: just men, corrupted by power.

In other words, it’s a drama.

While there are many forms of ‘drama’ in the broad spectrum, typically, the term ‘drama’ means that a subject is more dramatic than humorous, with a primary element of the story being conflict, but not necessarily of the physical kind. It’s a story with more of an emphasis on who the story is happening to, and why, with less concern for what exactly is happening.

Such is the case for Mr. Smith Goes to Washington.

Mr. Smith is a story about real people, people you or I might know, from the virtuous Jefferson Smith to the cynical Ms. Saunders, to the corrupt, but still human, politicians, some malicious, some merely led astray from their previous values. This is not a story of ‘heroes vs. villains’, this is a story about the ‘Right Thing to Do’, and the people with the courage to do it.

And that’s most of its appeal.

Capra’s passion is for people in this film, the everyday, the ordinary, the ‘Little Guy’ who becomes, not a dragonslayer, but a man with the opportunity to truly do some good, faced with tough decisions. It’s a story full of heart, sprinkled with humor, and loaded with humanity as it views, through very human lenses, the world of politics through a protagonist who’s meant to be a fish out of water.

That is Mr. Smith’s legacy.

The story isn’t groundbreaking. The cinematography isn’t breathtaking. The writing isn’t jaw-dropping. But the people, the characters, live and breathe on the screen as people, characters that the audiences love, and cheer for. We root for these people because of the drama of the situation, and the time and care that the film takes to delve into them.

That, more than the politics of the situation, is the reason people return to this film again and again.

And that, the people, the characters, is what we’ll be turning our attention to next time.

#Mr. Smith Goes to Washington#Mr. Smith Goes To Washington 1939#1939#30s#Film#Movies#Political#Drama#Comedy#James Stewart#Jean Arthur#Claude Rains#Edward Arnold#Thomas Mitchell#Frank Capra

25 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

#Mr. Smith Goes to Washington#Mr. Smith Goes To Washington 1939#1939#30s#Film#Movies#Political#Drama#Comedy#James Stewart#Jean Arthur#Claude Rains#Edward Arnold#Thomas Mitchell#Frank Capra

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mr. Smith Goes to Washington: The Story

The story of Mr. Smith Goes to Washington opens up, not with the titular character at all, but with a hubbub of telephone conversations reporting the sudden and unfortunate death of American senator: Samuel Foley.

Instead of mourning the death of this political figure, the cogs in the political machine immediately begin turning to try to find a replacement, as Senior Senator Joseph Harrison Paine (Claude Rains) makes a long-distance call to Governor Hubert “Happy” Hopper (Guy Kibbee) to deliver the news, who in turn relays the word to party leader Jim Taylor (Edward Arnold), asking for instructions as to making choice of a successor.

Hopper, you see, is Taylor’s ‘yes man’, happy to have his strings pulled as long as he remains in a position of wealth and power, and turns to him for advice to find someone to fill in as interim senator to fulfill the late senator’s term. The conditions are simple: they need someone who’s not going to cause a problem, someone who doesn’t know much about politics.

They need another ‘Yes Man’, specifically one who isn’t going to raise any questions about the Willet Creek Dam project.

Why, you may ask?

Taylor, as it turns out, has developed a plan: with the use of false names, the political machine bought the land surrounding Willet Creek, with the intention of passing a bill in order to construct a false dam in the area. Once the land was discovered to be the site of a new government building project, the land would be sold back to the state: for outrageous prices. Such a scheme, besides being morally reprehensible and dishonest, is guaranteed to make involved parties very, very wealthy.

Such is the necessity for a ‘Yes Man’.

After both suggested candidates are soundly rejected for one reason or another, the weak willed Governor Hopper learns at the dinner table through his children that they have an idea for a candidate: the leader of the Boy Rangers, Jefferson Smith (James Stewart), a man personally responsible for putting out a forest fire. This great patriot, as one of the boys tells Hopper, is also well read, especially in terms of his history, and publishes the Boy Rangers newspaper.

Hopper makes this delicate decision by flipping a coin: when the coin stands on edge, and he catches a glimpse of a paper praising Smith’s heroics, he decides Smith it is.

After all, Smith isn’t even a politician. It’ll be easy to keep him in check.

A banquet is held to honor the new Senator, during which Smith, in a mildly awkward speech, explains how he feels this is some sort of mistake. With utter naivete and no clue of the part he’s been recruited to play in the political scheme, he goes on to say how he idolized the state’s representative, Senator Paine, as a man of virtue.

“Just to sit here with him is a very great honor for me, because I remember Dad used to tell me that Joe Paine was the finest man he ever knew. I don’t think I’m gonna be much help to ya down there in Washington, Senator. I’ll do my best. With all my might, I can promise ya one thing – I’ll do nothing to disgrace the office of the United States Senate.”

On the train ride to Washington, Paine, who together with Clayton Smith, Jefferson’s father, used to fight for ‘lost causes’, tells Smith how much of Clayton he sees in Smith. Clayton Smith, as it turns out, was murdered over his newspaper desk while fighting a syndicate, dying for what he believed in.

Smith remembers his father’s words: “Dad always used to say the only causes worth fighting for were the lost causes.”

A moment later, he adds: “I suppose, Mr. Paine, when a fella bucks up against a big organization like that, one man by himself can’t get very far, can he?”

Once the train arrives in Washington, Smith is bombarded within moments by the fast-paced nature of the nation’s capital. Smith and his homing pigeons are instantly out of place, not only amongst the well-polished, smooth senators, but also amongst the general population of Washington DC, and indeed the city in general. Undeterred, Smith wanders off from Paine, transfixed by the distant view of the Capitol Dome and the setting of so much of the nation’s history.

Meanwhile, Smith’s entourage goes totally berserk at the sudden disappearance of the new senator and puts in calls to track him down, including one to his new secretary, Saunders (Jean Arthur).

After several hours, still at Smith’s new office, Saunders, quite fed up of waiting around for her new boss to arrive, complains to her friend, a hard-drinking reporter named Diz how she should have cleared out before. Moments later, Jefferson Smith finally arrives, where Saunders roundly chews him out for disappearing and leaving everyone waiting. He apologizes and explains where he was: exploring Washington DC’s many monuments, and Saunders bundles him into a taxi to take him over to Senator Paine’s house, a ride during which Smith continues to point out the historical landmarks of the city and remarks that he intends to go to Mount Vernon, the Washington homestead, tomorrow to ‘get in the mood’ for taking his Senate seat.

Saunders, clearly amused by the new senator, sets up a press conference, during which the hungry press devour a naive Smith alive: full of questions about any ‘pet projects’, or any new ideas. Smith, excited, tells them about an idea he’s had to set up a national boys’ camp in the country, designed to be both fun and educational, instilling good values in boys who may come from less fortunate circumstances. During the interview, he does everything from admit his mild crush on Senator Paine’s daughter to perform bird calls on request, leading to the papers the next day to do what papers do best: exaggerate and misquote. The following morning, the newspapers are full of out of context quotes and pictures of Smith looking foolish. Meanwhile, Saunders, tired of the Washington life, admits she wants to quit unless she’s suitably compensated for ‘babysitting’ Smith. Senator Paine convinces her to stay, willing to bribe her to keep Smith away from the Willet Creek bill.

It is at this point that we as an audience fully get the picture of all the major players, and how they will begin to interact with each other: specifically against each other.

The titular Mr. Smith, not even established until a few minutes into the film proper following the inciting incident, is very clearly set up as a stark contrast against every other individual in Washington: he is slower paced, but not stupid, honest, earnest, and idealistic.

Every other major player in this film as of yet has ulterior motives: is playing an angle. Every solitary character has a goal that they are trying to get at, and none of them are going by it honestly: Paine and the other politicians surreptitiously attempting to profit off of the Willet Creek Dam, focusing on public opinion for re-elections, even focusing on a ‘stooge’ to bring into office so as not to be questioned. Even Paine, who was once idolized by Smith and a freedom fighter, has fallen into the cynical rat race of politics. Saunders, not even a politician, finds herself cynical and tired of the same game, but still willing to play it in order to get her rewards for it in cash, which is what everyone seems to be motivated by. The reporters are only interested in their flash story, not who is misrepresented through it.

And in the middle of all the hubbub is Mr. Jefferson Smith, without a soul in the world to rely on, with no idea of how, or why, he is in the position he is in. And yet, he is no less likable for it. The rest of Washington stands against him, and without knowing it, he pushes right on through.

Smith is sworn into office, defended by Paine to a senator who attempts to block it on grounds of his showing in the papers. Following being admitted into the office of senator, Smith gets a glimpse of the offending papers for the first time: and proceeds to angrily track down the reporters who were there, who defend themselves, explaining to him the way the press works around here. They caution him about how politics ‘really’ works, warning him about his attitude getting him into more trouble.

Smith, disillusioned, debates stepping down from his new position, coming to the realization that he’s been placed in the senate seat as an honorary stooge. Paine talks him out of it, explaining that he shouldn’t worry about what the upcoming bills say, instead encouraging him to focus on a project of his own: the national boy’s camp.

With renewed enthusiasm (and the help of Saunders), Smith begins to draft his bill, listening to Saunders’ advice on how long it takes for bills to pass. Somewhat deflated, Smith and Saunders draft the bill overnight, alternating ‘shop talk’ with getting to know one another, with Saunders’ jaded worldviews softening slightly underneath Smith’s optimism. During the conversation, Smith finally pries her first name out of her: Clarissa.

During his dictation of the bill, Saunders discovers where exactly this boys’ camp is to be held: around Willet Creek, the same patch of land that is currently being held for the dam. Stunned, Saunders warns Diz the next day of the drama about to take place, predicting that most of the major players will depart the floor once the name of the creek is uttered.

Smith’s proposal, uttered with uncertainty, is nonetheless met with wild support from the boy rangers sitting in the balcony and other senators, while Paine and McGann exit the room to discuss what the next move is. Paine decides to use his daughter, who Smith is rather taken with, as a distraction, using her to keep him out of the way for the next Senate meeting. Learning about it, Saunders finds herself feeling rather protective of her charge, upset at the underhanded way he’s being led around. Disgusted, she ends up blurting out the entire plan about the dam to Smith.

Suspicious of the proposal for a dam in an otherwise worthless location, Smith brings it up to Paine, who firmly, but calmly shuts him down, despite Smith’s accurate statement that he knows that Taylor’s out to get graft.

Now nervous about the oblivious ‘boy ranger’ getting wise to what’s going on, Taylor comes to Washington, coming up against Paine, who finds himself struggling with his conscience:

“Your methods won’t do here. This boy’s a Senator. However it happened, he’s a Senator. This is Washington, Jim…This boy’s different. He’s honest. Besides, he thinks the world of me. We can’t do this to him!”

Taylor won’t back down, stating that if Smith doesn’t fall in line, then Taylor will knock him to pieces, threatening Paine’s career if he doesn’t continue with the plan. Paine, cowed, agrees to back down.

Smith has an opportunity to meet Taylor himself, and within moments of Taylor attempting to buy his silence about the Willet Creek dam, informing Smith that Taylor made Paine the man he is today due to him. Smith calls him a liar to his face, unmoved. Despite Taylor’s, and then Paine’s best efforts, Smith remains silent, neither arguing nor agreeing to participation in their scheme, and Smith leaves, dejected and thoroughly disillusioned about his heroes, his Silver Knight.

The following day, at the Senate, Smith stands to question the section regarding the Willet Creek Dam. Realizing he’s about to be exposed, Paine, who had been sympathetic to Smith until now, immediately talks over him, diverting the attention of the Senate body and accusing Smith of the crime that Paine and his co-conspirators are currently committing, complete with falsified evidence.

Unable to prove his innocence at the hearing, and unable to make Paine meet his eye, Smith leaves the Senate for a midnight visit to the Lincoln Memorial, reading the words of the Gettysburg Address carved into the wall before taking a seat on his bags, packed and ready for him to return home with his tail between his legs, and begins to weep.

Saunders emerges from the shadows, stating she thought she’d find him here. Smith answers her, completely dejected:

“You sure had the right idea about me, Saunders. You told me to go back home, keep fillin’ those kids full of hooey. Yeah. Just a simple guy you said was still wet behind the ears. A lot of junk about American ideals. Yeah, that’s certainly a lot of junk, all right…I don’t know. This is a whole new world to me. What are you gonna believe in? And a man like Paine, Senator Joseph Paine gets up and swears that I’ve been robbin’ kids of nickels and dimes – a man I’ve admired and worshipped all my life. I don’t know. There are a lot of fancy words around this town. Some of them are carved in stone. Some of ’em, I guess the Taylors and Paines have put ’em up there so suckers like me can read ’em. Then when you find out what men actually do – Well, I’m gettin’ out of this town so fast and away from all the words and the monuments and the whole rotten show.”

Saunders, previously a figure of cynicism, full of disdain for Smith’s idealistic nature, does the unthinkable: she tells him to stand and fight.

“Your friend Mr. Lincoln had his Taylors and Paines. So did every other man whoever tried to lift his thought up off the ground. Odds against ’em didn’t stop those men. They were fools that way. All the good that ever came into this world came from fools with faith like that. You know that Jeff. You can’t quit now. Not you! They aren’t all Taylors and Paines in Washington. Their kind just throw big shadows, that’s all. You didn’t just have faith in Paine or any other living man. You had faith in something bigger than that. You had plain, decent, every day, common rightness. And this country could use some of that. Yeah – so could the whole cock-eyed world. A lot of it. Remember the first day you got here? Remember what you said about Mr. Lincoln? You said he was sitting up there waiting for someone to come along. You were right! He was waiting for a man who could see his job and sail into it. That’s what he was waiting for. A man who could tear into the Taylors and root ’em out into the open. I think he was waiting for you Jeff. He knows you can do it. So do I.”

The next day, Smith walks back into the Senate Chamber, cheered on by Saunders in the gallery. The report comes in for Smith’s expulsion, and he is allowed to speak, recognized by the chair for a few moments longer. With that, Smith begins his final gambit, his last chance not only for the boys camp, but to expose the true corruption in the Senate, and declare his own innocence:

He begins a filibuster.

Without yielding the floor, Smith cannot be interrupted or stopped now as long as he keeps talking, and standing on his own two legs. Yielding means defeat, and ousting. Smith’s option now is to keep standing, and keep talking to stall the vote for his own expulsion.

Pressing on, refusing to yield the floor to Paine, or any other senator for anything other than a question, Smith stalls for time as Paine leaves the room, followed by the disgruntled senators, prepared to speak until his message gets out.

During Smith’s twenty three hour filibuster, Taylor’s machine stomps out every method of news that could possibly get out concerning the truth about his involvement, his own newspapers blasting Smith for the filibuster as Paine, too sickened by the situation, gives up, unable to do anything more to help the machine.

Saunders, steadily coaching Smith from the balcony, sends a note down to him suggesting he read the Constitution aloud to continue to stall, confessing that she’s in love with him in the same note. Bolstered, Smith continues, clearly exhausted as Saunders, aware of the muzzling of the media, dictates a letter to Smith’s mother back home and his Boy Ranger’s newspaper: the only free press available that’d be able to print Smith’s side of the story.

Even then, Taylor’s long arm stomps out the truth, as his men force the paper down, confiscating at whatever cost, even to the injury of some of the boys distributing. Eventually, Senator Paine is granted permission to bring in ‘evidence of the response’ of the state, hundreds of telegrams manufactured by Taylor and his followers demanding that Smith yield the floor.

Devastated, a hoarse, weak Smith turns to Paine, and speaks.

“I guess this is just another lost cause, Mr. Paine. All you people don’t know about lost causes. Mr. Paine does. He said once they were the only causes worth fighting for. And he fought for them once, for the only reason that any man ever fights for them. Because of just one plain simple rule: ‘Love thy neighbor.’ And in this world today, full of hatred, a man who knows that one rule has a great trust. You know that rule, Mr. Paine. And I loved you for it, just as my father did. And you know that you fight for the lost causes harder than for any others. Yes, you even die for them. Like a man we both knew, Mr. Paine.”

At twenty-three hours and sixteen minutes, Smith collapses with exhaustion. Paine rushes out of the senate room, and attempts to kill himself, the other senators forcing the gun away as he cries out his own guilt, running back into the senate:

“Every word that boy said is the truth! Every word about Taylor and me and graft and the rotten political corruption of our state. Every word of it is true. I’m not fit for office! I’m not fit for any place of honor or trust. Expel me!”

Smith is carried out, still unconscious, as the gallery and Senate explode into wild cheers, and the President of the Senate sits back, unable to control the chaos.

It’s over. Smith, and truth, have won.

The end.

Despite being long hailed as one of the most idealistic films in American history, a hallmark of director Frank Capra’s filmography, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington is actually a very cynical film about a very idealistic man.

Throughout the entire film, almost every character acts out of self-serving cynicism: the politicians in order to maintain their machine and grip, the reporters making a fool out of Smith in order to sell a headline, even Saunders acts in her own self-interest, until something changes her mind: Jefferson Smith.

Smith enters the scene as the typical Capra character: idealistic and Good. At no point is he portrayed as stupid, just ignorant of how the political machine works. He’s educated, he’s earnest, and he wants to do the right thing, and that’s what sets him apart so firmly from the rest of the cast: Jefferson Smith is the lone holdout representing the ideals America was supposedly founded on.

The film never looks down on him for this, portraying every other character’s reactions to him as either good or bad: Saunders initially finds him foolish until she spends more time with him. Paine alternatively takes advantage of and pities him. Taylor mocks and attempts to exploit him. But throughout it all, Smith stands firm, and really, that’s the victory of this film.

Mr. Smith Goes to Washington is not constructed like your typical ‘hero’s journey’ story. The major climax is simply the main character stalling for time and speaking his mind: for twenty three hours, Smith just talks, and no one listens. He never overthrows Taylor. He never actually proves his innocence. He and Saunders never even confess their feelings for each other in person.

Throughout the entire film, our hero never really changes, foundationally. He overcomes his own discouragement with some help, and he gets a sharper hold on how DC actually works, but never does he lose his idealism. The day is not won by Smith becoming something else, but rather Smith using the system and playing it his way.

And he doesn’t even win. Not really.

This isn’t a ‘slaying of dragons’ moment. Smith, until the last two minutes of the film, is destroyed: completely defeated. It’s almost simply by matter of principle that he’s even still talking, and the movie continues after he collapses, following Senator Paine, overcome with grief and guilt, finally coming clean and admitting his involvement, clearing Smith’s name.

Smith isn’t the one who truly ‘saves the day’. At the end of the day, Paine, regretting his own fall from grace, is the source of the film’s closure: standing in contrast to Smith’s resolve and innocence, Paine gives himself up and admits his own guilt.

So…how does that translate, story wise? Are we compelled as an audience to root for this character in a story where he doesn’t even ‘save the day’? Are we invested in his story?

Simply, yes.

There’s a reason this movie is held up as an American classic. The script is tight and well knit, perfectly balancing ideals and values: idealism vs. cynicism, selflessness vs. selfishness. It is that balance, that tug back and forth between right and wrong that keeps us invested in characters that we care about: Smith isn’t superhuman, but he is Good, and we as an audience want to see him win the day.

But even more importantly, we want to see Justice. We want to see the Right thing happen, because in the end, the story is about more than Smith. The story is about right vs. wrong, one of the oldest and greatest themes ever told, expressed through characters that are just as human as you or I.

And in the end, Smith, not through any great victory of his own, but simply by his character, comes out on top. He wins.

And there’s nothing audiences love more than a good ‘against the odds’ story.

In the upcoming articles, we’ll be taking a look at some more of the fascinating facets that make up Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, so please, stay tuned for next time! Thank you all so much for reading and I hope to ‘see’ you in the next article!

Share this:

#Mr. Smith Goes to Washington#Mr. Smith Goes To Washington 1939#1939#30s#Film#Movies#Political#Drama#Comedy#James Stewart#Jean Arthur#Claude Rains#Edward Arnold#Thomas Mitchell#Frank Capra

6 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

#Mr. Smith Goes to Washington#Mr. Smith Goes To Washington 1939#1939#30s#Film#Movies#Political#Drama#Comedy#James Stewart#Jean Arthur#Claude Rains#Edward Arnold#Thomas Mitchell#Frank Capra

1 note

·

View note

Text

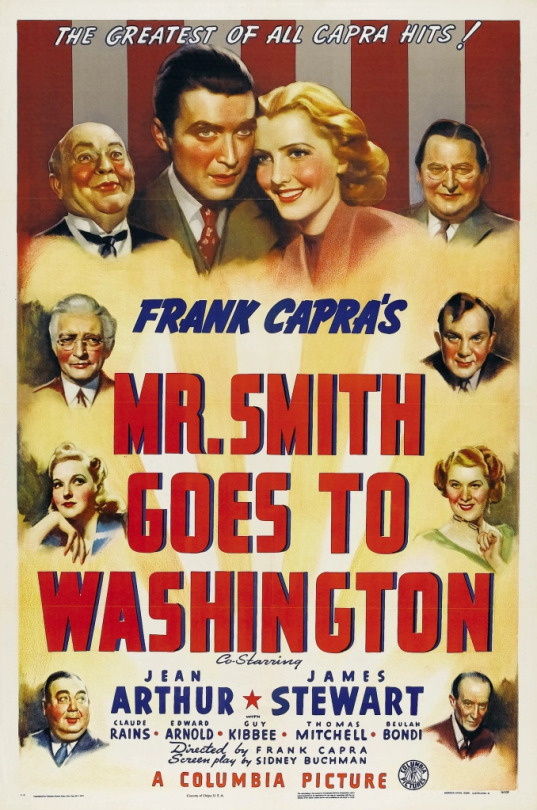

Mr. Smith Goes to Washington: Legacy and Impact

1939 was quite a year for movies.

Gone with the Wind adapted the story of Scarlett O’Hara and her plantation dramatically for the big screen, telling the story with grand, sweeping visuals that took the Oscars by storm. The Wizard of Oz took the fairy tale of a girl from Kansas transported to a magical land and turned it into a classic showcase of talent and spectacle that has remained acclaimed to this day. Stagecoach re-invented the western and put an actor named John Wayne on the map of Hollywood.

And a film called Mr. Smith Goes to Washington won ‘Best Original Story’ at the Oscars, and nothing else.

By 1939, director Frank Capra was already established fairly decently in Hollywood. After inventing the modern romcom with It Happened One Night in 1934, and creating the heartwarming story of a bumbling bumpkin inheriting a fortune in Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, Capra hit it big in 1938, with his adaptation of the Broadway show: You Can’t Take It With You. By 1939, he was prepped and ready for another smash hit.

Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, originally meant to be the sequel to Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, seemed to fit the bill well enough.

Released in October of 1939, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington was a box office success, capitalizing on Capra’s previous hits and catapulting lead actor James “Jimmy” Stewart to stardom, solidifying Jefferson Smith as one of the most iconic characters in American cinema. For years following its release in that crowded 1939 movie season, the film has been beloved as a classic Hollywood masterpiece, another triumph amidst 1939’s impressive catalog. Nominated for eleven Oscars but only winning one, the film is now heralded as an American paragon, a patriotic film, among some of the greatest films of all time, and looking back, it can be easy to see why that would be so.

Interestingly enough, at the time of its release, this wasn’t the case.

Mr. Smith Goes to Washington debuted in Constitution Hall in Washington, and was immediately attacked by the press for an anti-American portrayal of politics, politicians, and Washington in general. There was even a concern about it’s showing overseas giving the ‘wrong impression’ of America, and yet, when American films began to be banned in German-occupied France, interestingly enough, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington was chosen as the last film many of these theaters showed.

Although the film was considered a box office success when it first came out, (the second highest grossing film of 1939 and third highest grossing film of the 1930s, behind Gone with the Wind and Snow White and the Seven Dwarves), and critical opinion (as well as audience opinion) outside of DC seemed favorable, it’s difficult to overlook the dark cloud that hung over it’s initial reception in the city it focuses the most on. Once one sees the film, it can be easy to see why there was such a ruckus raised, but still, one has to wonder, was one reaction or the other a bit extreme?

After all that hubbub, over eighty years later, the film has a reputation for being an American classic, one of Frank Capra’s best pictures, named as one of the best films of the prestigious 1939 movie season, even admitted into the United States National Film Registry in 1989 due to being deemed “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant”. Ironically, even the government, who took the film so badly at first, eventually came to value it as a masterpiece.

So, what changed?

A lot of things. You can point to the ever-turbulent political landscape of post-Vietnam America, to the Watergate scandal’s removal of trust in America’s leaders, or the evolving tastes of the average movie-goer as to why it is that Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, despite itself not changing over the years, seems to have inspired such a wild turnaround in public opinion, becoming a juggernaut representation of American ideals and optimism against all odds.

The question is, why?

Was it the film’s biting political satire? The iconic performances by classic actors? The sharp script brought to life by a director that has long since been considered a master at his craft?

These are all the questions we’re going to be taking a look at in the weeks ahead. Stay tuned, and thanks so much for reading.

#1939#30s#Film#Movies#Mr. Smith Goes to Washington#Mr. Smith Goes To Washington 1939#Political#Drama#Comedy#James Stewart#Jean Arthur#Claude Rains#Edward Arnold#Thomas Mitchell#Frank Capra

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939) 2 hrs, 9 minutes

A naive youth leader is appointed to a seat in the senate, intended to be a pawn for other politicians. When his idealistic plans conflict with a corrupt scheme for personal profit by other senators, Washington DC at large wages war against Jefferson Smith’s character, forcing him to take to the Senate floor to defend himself and speak the truth.

Genre: Political/Comedy/Drama

Rating: Passed

Director: Frank Capra

Cast: James Stewart, Jean Arthur, Claude Rains, Edward Arnold, Thomas Mitchell

Release Date: October 19th, 1939

8.1/10 on IMDb, 96% on Rotten Tomatoes, 73% on Metacritic, 90% of audiences enjoy this movie.

Join us as we take a look at a satirical story about a wide-eyed idealist swamped with corruption from the 1930s! Welcome to our analysis of Mr. Smith Goes to Washington.

youtube

#1939#30s#Film#Movies#Mr. Smith Goes to Washington#Mr. Smith Goes to Washington 1939#Political#Comedy#Drama#James Stewart#Jean Arthur#Claude Rains#Edward Arnold#Thomas Mitchell#Frank Capra

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

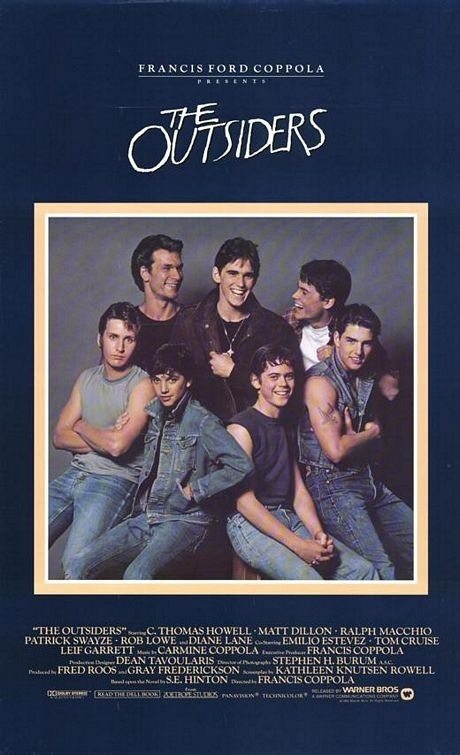

Coming of Age: The Outsiders

There are few experiences that are told in stories that are truly universal.

I’m not talking about universal themes, ideas that bring people together, like good vs. evil, or loss, nor am I talking about universal dreams that people have, of making something of ourselves, of being remembered, or of finding true love. These are things that humanity has told stories about as long as storytelling has been an art form.

However, while most of us, as audience members, can get behind stories that tell us what we want to go through, it’s a little bit rarer for a story to truly show us what we are going through.

Think about it. Not all of us have fallen in love, or been on the run from the law, or had to fight off a horde of zombies, or driven cross-country, or moved, or taught an entire town of people how to dance. These are stories full of ideas that we may be able to relate to, but not necessarily experiences.

Which isn’t a bad thing.

Humans don’t always want to go to theaters to watch their life story, their experiences, things they themselves have gone through. For many years, storytelling has been a form of ‘escape’, taking feelings that humans share and using those feelings, coupled with imagination, to tell stories that seem bigger than our own.

However, there are a few exceptions, such as when it comes to the genre of coming of age.

The ‘coming of age’ genre is described by TVTropes as: ‘A story featuring an adolescent making the mental leap from child to adult.’ If this is the case, then the coming of age story is, in fact, one of the few genres that is a universal experience, with each of these stories focusing on the event of maturity, something that virtually all audiences have to grapple with at some point or another.

Coming of age is a bit of a different focus for a story for one important reason: it is both a theme and an event. The idea of coming into your own, becoming an adult, is one that doesn’t necessarily happen on a timetable, but at some point, everyone has to face that experience. A coming-of-age story comes at it’s audience with one simple lesson: One way or another, we all have to grow up.

As a result, it’s a fairly popular subgenre, with a fairly wide variety of topics:

Getting a driver’s license. First love. Arguments with parents. Struggles with identity. Loss of innocence. Planning a future. These are all common elements often found in these sorts of stories, and whether in big ways or small, many of these types of storylines tend to find their way into many films about youngsters, such as Stand By Me, American Graffiti, Racing with the Moon, and plenty more. As it turns out, a lot of stories have a lot to say about growing up.

One of these stories is The Outsiders.

The story of The Outsiders began as a novel, written by S. E. Hinton in 1967. The book details the life of Ponyboy Curtis, a teenager involved in a gang of ‘greasers’ who is raised by his older two brothers following the death of their parents, as he becomes involved in the conflict between the ‘greasers’, and a gang of upper-class teenagers, the ‘Socs’.

The book was released to a fair amount of controversy, controversy that still exists surrounding it to this day (due to the family dysfunction, smoking, drinking, language and gang violence portrayed within), but immediately, something about The Outsiders resonated with a young audience, to the point where it codified, if not invented, the Young Adult genre of fiction and is now included in most American school curriculums for English class.

In 1983, Francis Ford Coppola directed a film adaptation of The Outsiders, with the help of S.E. Hinton herself, casting a series of up-and-coming nobody actors who were all quickly catapulted to fame following their involvement with the film. The movie adaptation has long been hailed as one of the most accurate book-to-screen translations of all time, and, much like the book, it became a very influential event in the lives of many young people since the time of its release.

The question is, why?

The Outsiders is widely regarded as one of the greatest ‘coming of age’ stories of all time, but, in all honesty, it doesn’t share a lot in common with the tropes and stories previously mentioned. Ponyboy’s parents are long gone, far removed from the picture of his life now, raised by his brothers Sodapop and Darrel. There’s no ‘learning to drive’, or choosing a future, there is instead the story of a boy dealing with the idea that division, and the hatred that comes of it, has dangerous consequences. This is a story about a lot more than just growing up. It’s about family, about friendship, about ‘staying gold’, remaining innocent and appreciating life, about class, about life and death. In the end, it is about a boy becoming a man, through circumstances that are far from ideal.

And the way it does so is all summed up with the most well-known quote from the story:

“Stay gold, Ponyboy.”

But before we explain that, we need some background.

Ponyboy Curtis is the youngest member of the Greasers, a gang that consists of, (among others) his two older brothers, the recently attacked Johnny Cade, juvenile delinquent Dallas Winston, alcoholic with a sense of humor Two-Bit Matthews, and Steve Randle, who works at the gas station with Sodapop.

The Greasers are in direct opposition with another gang, the Socs, much wealthier kids from the other side of town. These are the ones who recently beat Johnny up, and, at the beginning of The Outsiders, attack Ponyboy as well, fought off by the other Greasers.

Instantly, the picture of the world that Ponyboy Curtis lives in is painted for us: a troubled kid, in a troubled neighborhood, plagued by violence from both sides.

At home, things aren’t much better.

Ponyboy is cared for by his two older brothers, Darrel, who gave up his opportunity to go to college in order to provide for the family unit, and Sodapop, who dropped out of school to work at a nearby gas station. While Ponyboy gets on fine with Sodapop, there is clear tension between him and Darrel, who is frustrated by Ponyboy’s disobedience with the rules of the house and disregard for his own safety.

There’s more to Ponyboy’s world than just the Greasers, ‘us’, and the Socs, ‘them’. During the story of The Outsiders, his perspective changes, multiple times, in fact.

Early in the story, Ponyboy meets Cherry Valance, a Soc girl who is nice to him, has a conversation with him, and seems to regret the gang rivalry. Although she isn’t wild about some of the company he keeps (especially Dallas), she doesn’t seem like the ‘other’ Socs. After meeting her, however, later that night, Cherry’s boyfriend, another Soc, and his friends attack Ponyboy and Johnny together, and in the ensuing scuffle, Johnny kills Cherry’s boyfriend in self defense. Terrified, the boys, with the help of Dallas, go on the run.

Later, the boys return, prepared to plead guilty to self-defense, but before they can, Johnny is badly injured while rescuing kids from a school fire, and is hospitalized, being hailed as a hero (along with Ponyboy and Dallas) in the process. Upon their return, a trial date is scheduled for the murder of Bob, Sherry’s boyfriend. Meanwhile, the Greasers and the Socs arrange a ‘rumble’, a brawl between the gangs.

After the rumble, Johnny succumbs to his wounds in the hospital, and Dallas, unable to cope, commits suicide via cop. At the trial, Ponyboy is found not guilty of murder, and Darrel is able to keep custody of him. Ponyboy returns to ‘normal life’, where Sherry ignores him at school, and Sodapop breaks up another fight between him and Darrel and convinces them to live peaceably together.

There’s more to it than that, of course, but that’s the bare bones basics. So, why does it matter in terms of a ‘coming of age’ story?

It all has to do with a Robert Frost poem.

While Ponyboy and Johnny are laying low from the law, Johnny watches a sunset, and remarks on how pretty it is. Ponyboy responds with a poem by Robert Frost, Nothing Gold Can Stay:

Nature’s first green is gold,

Her hardest hue to hold.

Her early leaf’s a flower;

But only so an hour.

Then leaf subsides to leaf.

So Eden sank to grief,

So dawn goes down to day.

Nothing gold can stay.

The words to the poem come up later, on Johnny’s deathbed, as he tells Ponyboy to ‘stay gold’. While it’s one of the most quoted lines from the film, it’s also one of the most important, from a thematic standpoint.

In both the context of the poem and the story, the idea of ‘staying gold’ is a simple one: remaining innocent, fresh, young. Nothing innocent can stay, everything grows up, matures, becomes tainted by the world.

In other words, the poem itself is about coming of age.

So, how does that apply to The Outsiders?

Throughout the story, our focal point, Ponyboy, doesn’t grow up physically. He’s the same age at the end of the story as he was at the beginning. Very little in his situation changes: he ends the story still living with his brothers, going to school. There’s no big transition in his life, he doesn’t strike out on his own, despite conflict with his authority-figure big brother, he remains roughly where he is.

But with that said, Ponyboy does come of age during this story, of a kind.

In The Outsiders, the idea of ‘coming of age’ isn’t ‘coming into your own’ in the sense of moving out on your own or becoming an adult, partially because Ponyboy, the main character, has seen what that looks like in every single person surrounding him: his oldest brother’s childhood gone as he is forced to take on the responsibility of being a ‘dad’. Sodapop drops out of school to work. Two-Bit is an alcoholic at a young age. Dallas is a delinquent, committing violent crime before he’s a full grown man, and Johnny kills a member of the rival gang, later commenting on it:

“Shut up about last night! I killed a kid last night. He couldn’t have been over seventeen or eighteen, and I killed him. How’d you like to live like that?”

In the end, that’s the story’s main point: not one of these boys should be this old already. Johnny shouldn’t have been attacked. Dallas shouldn’t be dead. Darrel shouldn’t be shouldering his entire family to keep them afloat.

And yet, this is where they are.

The rumble in The Outsiders is not a righteous battle between two sides. It is two groups of kids, beating each other nearly to death. The death of Bob is tragic, as is Dallas’s end, and Johnny’s. These are children, and Ponyboy is too.

The point of the Robert Frost poem, the idea of ‘staying gold’, and why Johnny wants it for Ponyboy, is, actually, the inverse of the typical ‘coming of age’ story. The idea of holding onto your innocence in the face of a world that tries to grow us up prematurely, is a central one to the story of The Outsiders, and the worst thing about it is that while it may be a lesson learned, it’s not one necessarily taken to heart.

Although Ponyboy is the youngest of the group, both physically and mentally, he has still seen far too much of the ugly side of the world: losing both his parents, the violent gang warfare, Johnny’s death and Dallas’s suicide-by-cop. Ponyboy is already forced to take part in a world too old for him, to the point where it’s jarring when he and Johnny are on the run and he pretends to be a kid playing soldier. It’s correct for his age group, but Ponyboy is already ‘too old’ for it.

But there is hope.

Ponyboy still watches the sunsets. He goes back to school, and he moves on, with Johnny’s words at his back. He is changed, yes, and he has grown up some: half man, half boy. He understands things now, like the fact that the Socs and the Greasers are not that different, and that Darrel loves him and wants what’s best for him, even if he isn’t the best at showing it.

But in the end, Ponyboy isn’t a man. Not yet. There is still time for him to watch the sunsets. There is time left, in the end, for him to stay gold.

Thanks so much for reading. I hope to see you guys in the next article.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

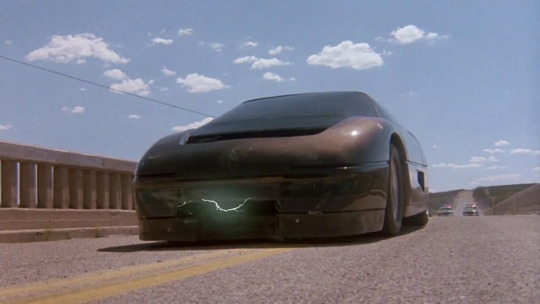

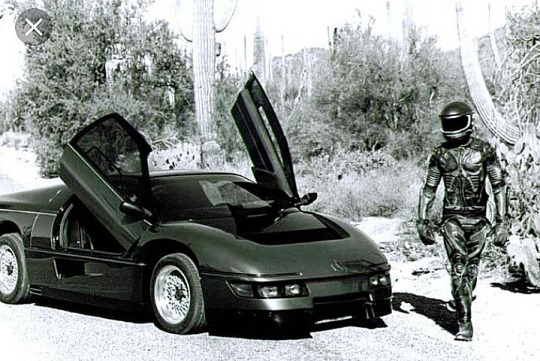

Movie Cars: The Wraith

The film The Wraith is a unique piece in our study of movie cars for a number of reasons:

One, it’s one of the lesser-known films. Following classics like Bullitt and Batman, The Wraith, a little film about a ghost taking revenge on the street-race gang that killed him is a smaller-scale film with an ensemble of cars that’s nothing to sneeze at: a Corvette Stingray, a ’66 Plymouth Barracuda, an ‘84 and an ‘87 Dodge Daytona, and a ’77 Pontiac Firebird Trans Am.

However, despite this impressive lineup of vehicles, the real main attraction of the film lies in the titular character’s vehicle: a ghost car portrayed by the Dodge M4S Turbo Interceptor, a pace car for the PPG-CART Indy Car World Series.

The Dodge M4S was originally built by Chrysler Corporation and PPG Industries, with the body design developed by Chrysler, and the finish (specially designed for the car) created by PPG Industries. Six copies of the car were produced in total; two of these copies were genuine stunt cars, made from molds of the original vehicle, with the other four merely ‘dummy’ cars, empty bodies on frames that were destroyed during production. The genuine article, the real Dodge M4S was used for close ups only.

The Turbo Interceptor was a marvel in terms of technology, costing approximately $1.1 million to build, with performance well worth the price. The car was powered by a Chrysler 2.2 liter four-cylinder engine that exceeded 194 mph that made the car a one-of-a-kind standout among other famous cars in film history.

However, after all that, in the end, The Wraith, and the Dodge M4S, was largely forgotten. With no specifically interesting car chases, or anything else really to recommend it, The Wraith, not exactly a stellar stand-out, went mostly unnoticed in a decade full of other, more impressive films. The car was cool, sure, but unlike films like Bullitt, not even the Turbo Interceptor could raise this film above obscurity.

So, why discuss it here?

For one: the car is cool. The Dodge M4S was one of the more unique stand-outs in a string of iconic film vehicles, with a basic design that was memorable to those who watched it. However, as we’ve discussed before, what makes a film car memorable or not isn’t always just the design or power: it’s utilization.

In Bullitt, the main spotlight vehicle is interesting because it’s the protagonist’s vehicle, a car that participates in a thrilling chase scene. In Batman, it’s the Batmobile, for crying out loud. In The Wraith?

The major player of the film is a ghost-car, a vehicle that arrives only when a major set piece is about to take place: the harbinger of doom for the film’s antagonists. It isn’t just a vehicle, it’s a supernatural phenomenon, an indestructible machine that isn’t entirely physical.

There’s a mystery surrounding every time the titular Wraith makes an appearance, especially tying in the arrival of a newcomer into the town bearing suspicious scarring identical to the wounds of the deceased Jamie Hankins. Without adding any specific abilities to the car, already, something is special about it: it’s a ghost car with a mystery intact, belonging to a vengeful spirit that only appears when he’s ready to challenge someone else in a street-race to the death.

And in the end, that’s the car’s major claim to fame.

The Wraith is largely forgotten among film fans in general, and even movie car buffs for the most part, due to any number of reasons. However, the memorable aspect of the film isn’t solely the car itself: it’s the purpose within the narrative. The car in The Wraith is unique in its utilization within the story itself, not belonging to a hero in a chase, or driven with a side of pure ‘cool’ factor. Whenever this car makes an appearance in the film, it’s a sign that an Event is about to happen, that there’s going to be another death, to move the story along. This is no mere vehicle, it is a harbinger of doom, shorthand to the audience that something important is about to happen.

Unlike traditional race cars, chase cars, and cars outfitted with tons of gadgets, the car from The Wraith is simply an apparition, a tool of revenge used to street-race, equal parts eerie and impressive. And that��s what makes this particular vehicle a stand-out among other movie cars.

Are the race sequences groundbreaking in the way that the chase from Bullitt was? No.

Is the car as iconic as the Batmobile? No.

However, there is a level of iconography and cool factor about a haunted race-car that lends The Wraith a level of memorability that has stuck with it, even if only in a relatively small circle of fans that remember it. In the end, is it a classic cinematic car? Debatable. But it definitely is one worth checking out.

Thanks so much for reading, I hope to see you in the next article.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Episode Spotlight: M*A*S*H, Season 1, Episode 17: Sometimes You Hear the Bullet

Frank Burns throws his back out and applies for a Purple Heart. Meanwhile, Hawkeye Pierce meets, and later operates on, an old friend and struggles with the decision of whether or not to send an underaged soldier home.

More than halfway through season 1, M*A*S*H wasn’t exactly killing in the ratings. The show wasn’t quite sure of itself yet, with tons of recurring characters that would end up dropped and other characters not yet added to the main cast. Airing at eight o’clock on Sunday nights, M*A*S*H was, at this stage in the game, a relatively normal sitcom, albeit one with a bit sharper sense of humor.

That all changed with Sometimes You Hear the Bullet.

I’ll show you what I mean.

The episode starts humorously enough: Major Frank Burns throws his back out during a rendezvous with Major Houlihan. He is placed into traction, where he applies for a Purple Heart for his ‘injury’. Meanwhile, Hawkeye is visited by an old friend and kindred irreverent spirit: Corporal Tommy Gillis, a journalist who signed up for the front lines as he writes his book: You Never Hear the Bullet, a book meant to be written from a soldier’s point of view, instead of a reporter’s.

A helicopter full of wounded arrive at the unit, and Gillis returns to his post.

Among the wounded is a young man with a burst appendix, a Private Wendell Petersen, who is very anxious to get back to the front lines. Hawkeye tells him that he has to rest for a few days before returning to his unit. This doesn’t stop Wendell from attempting to steal an army jeep to try to get back, afraid that he was going to be sent home.

After talking with him, Hawkeye figures out the truth: Wendell Petersen is actually Walter Peterson, and he’s not even sixteen years old.

It turns out that Walter posed as his brother, Wendell, and entered the war to impress his girlfriend back home by returning with a medal. He begs Hawkeye to keep his secret, and, after returning him to his bed, Hawkeye agrees.

Shortly, more wounded arrive, and among them is Tommy Gillis. Hawkeye operates on him, but even his best is not enough, and he dies on the operating table after telling Hawkeye that he did hear the bullet. Hawkeye tries to revive him, but Colonel Henry Blake orders him to move on to save another life.

Afterwards, Hawkeye breaks down crying.

“Henry, I know why I’m crying now. Tommy was my friend, and I watched him die, and I’m crying. I’ve watched guys die almost every day. Why didn’t I ever cry for them?”

“Because you’re a doctor.”

Hawkeye asks what that means, and Henry answers with one of the greatest lines in the show’s history.

“I don’t know. If I had the answer, I’d be at the Mayo Clinic. Does this place look like the Mayo Clinic? Look, all I know is what they taught me at command school. There are certain rules about a war. And rule number one is young men die. And rule number two is, doctors can’t change rule number one.”

Right then and there, Hawkeye decides to change rule number one in some small way, and calls the MPs on Private Wendell, really Walter, outing the fact that he’s underage. Walter, outraged, tells Hawkeye that he’ll never forgive Hawkeye for the rest of his life.

Hawkeye replies: “Let’s hope it’s a long and healthy hate.”

In one final scene (one that’s usually cut from syndication), Henry Blake begins to present Frank with his Purple Heart, only to find it replaced with a purple earring, while outside, Hawkeye pins the Purple Heart on Walter to make up for turning him in, sending him home, but home a hero.

The end.

Sometimes You Hear the Bullet is considered one of M*A*S*H’s best episodes for a reason. This is an early episode, one that is regarded as a tone and trend setter for the rest of the series in terms of both storyline balance (one or two serious plotlines, one humorous), and content itself, one of the first episodes to sit down and truly explore the characters within this tragic situation. At this moment, M*A*S*H ceased being a comedy show and became a dramedy, with one of the most memorable moments and exchanges in the show’s long history.

While this episode may seem like a standard half-hour of television, at the time, especially for this show, it was something different. It was no longer a slapstick grittier Hogan’s Heroesque irreverent comedy about soldiers, it was a show about a group of people stuck in the middle of a war, with death all around them. And no matter how good Hawkeye, or any of the doctors, are at their jobs, they’ll never be able to save everyone.

It’s sobering, but it’s a truth that the show had, for the first time, truly explored, and it’s that initial exploration, that glimmer of what this show was going to become, that puts this episode under so much recognition: Sometimes You Hear the Bullet was the warning sign, the first moment that the writers got a handle on the show that would become a classic.

Of course, it has it’s problems.

Not tonal ones, at least, not exactly. Throughout its entire run, M*A*S*H often had two or three plots going, one serious, one humorous. This is a smart strategy: balance out the dark with the light, giving each episode a more even feeling instead of being too much one or the other. Although the show would get darker and more serious as time went on, the writers never abandoned this plan, allowing M*A*S*H to remain a consistent dramedy throughout the show’s run, keeping the audience laughing and crying at the same time.

In the case of Sometimes You Hear the Bullet, the ‘funny’ subplot is obvious: Frank Burns and his Purple Heart. The other two storylines are the serious ones: Hawkeye’s friend, as well as the underaged soldier. However, in most cases, as in this one, these plotlines inevitably intersect, and it’s here that this particular episode might cause a few problems.

I mentioned that the final scene in the episode is typically cut from syndication: the sequence where Frank’s purple heart is stolen and given to the underaged soldier, instead. While this scene may not, at first, seem inherently out of place within the context of the rest of the episode, swinging from comedy to drama within a minute, there are those who believe that this scene unintentionally undermines the rest of the episode, or the main thrust established a few moments earlier.

And those people aren’t exactly wrong.

I certainly agree that the episode would have been stronger had it ended with the soldier’s final interaction with Hawkeye been proclaiming his hatred, only for Hawkeye to soberly respond that he hopes it’s a long and healthy hate. Changing that to this new ending, where Hawkeye sends him home with a medal, seems almost out of character for Hawkeye, taking away some of the sincerity and severity of the message just a moment earlier. The idea that this soldier could bring himself to forgive Hawkeye so soon, before realizing what exactly he’d been saved from, seems a little disingenuous after the weight previously given to this subplot.

In later episodes, it’s possible, even probable that this episode wouldn’t have ended tied in such a neat bow. But that’s one of the things that’s so interesting about this episode.

Sometimes You Hear the Bullet isn’t the first episode of ‘true’ M*A*S*H as it would be remembered in the future, but it is the first episode where M*A*S*H comes into its own themes, looking hard at war, and the toll it takes not only on the soldiers, but on the surgeons, as well. Before this, for the most part, ‘characters’, friends of the cast, did not die on the operating table. Not when Hawkeye could save him.

But I’m going to quote Hawkeye from another season 1 M*A*S*H episode, Yankee Doodle Doctor, as I think that it sums up this the point of this episode pretty well:

“Three hours ago, this man was in a battle. Two hours ago, we operated on him. He’s got a 50-50 chance. We win some, we lose some. That’s what it’s all about. No promises. No guaranteed survival. No saints in surgical garb. Our willingness, our experience, our technique are not enough. Guns, and bombs, and anti-personnel mines have more power to take life than we have to preserve it. Not a very happy ending for a movie. But then, no war is a movie.”

That right there is the point of Sometimes You Hear the Bullet, to the point where the doomed Tommy Gillis even references the film tropes of a young, fresh-faced kid hearing the bullet that kills him. This is the message that Hawkeye must grapple with: he cannot save everyone.

No matter how much he knows, how good he is, he can never save everyone. No guaranteed survival.

It’s sobering, but it’s the truth. And it’s what makes this episode so memorable.

M*A*S*H at this point was still mostly a comedy, a series full of jokes and the occasional serious moment, and it would continue to be so for another few years. But it was this episode, episode seventeen of the first season, that signaled to audiences that this show could be more than that. It could make you laugh, sure, but it could make you cry, and it wasn’t that surprising: this was war.

In short: by itself, is Sometimes You Hear the Bullet one of the greatest episodes of television, or even M*A*S*H, ever written? Maybe. Maybe not. But what it is, without much doubt, is the first sign of maturity in a show that had a lot of growing up to do.

Whether the shift was instantaneous or not, the fact is, Sometimes You Hear the Bullet was a game changer in the show’s history, the first break in format that truly showed audiences what they could expect in the years ahead.

On top of that? It’s just a good episode.

The plot balance is decent, without too much mood-whiplash that could so easily occur in a war dramedy. The characters, decently familiar to audiences by now, all work off of each other just as well as ever, funny, interesting, and heartfelt in turn. It’s an example of early M*A*S*H at it’s best, overshadowing many first season episodes with a level of depth previously mostly unexplored, delivering on every scene and remaining mostly genuine. It’s an engaging episode, full of memorable moments that are thoughtful and earnest, making this episode a standout, a moment in television history, and an unmissable installment for avid watchers of M*A*SH, and television fans in general.

Don’t forget that the comment box is always open for anything from suggestions and discussion ideas to questions and conversations! Thank you guys so much for reading, and I hope to see you guys in the next article.

#TV#Television#Episode Spotlight#M*A*S*H#70s#TV-PG#War#Drama#Comedy#Alan Alda#Loretta Swit#Jamie Farr#William Christopher#Wayne Rogers#McLean Stevenson#Larry Linville#Gary Burghoff#Mike Farrell#Harry Morgan#David Ogden Stiers#Larry Gelbart

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

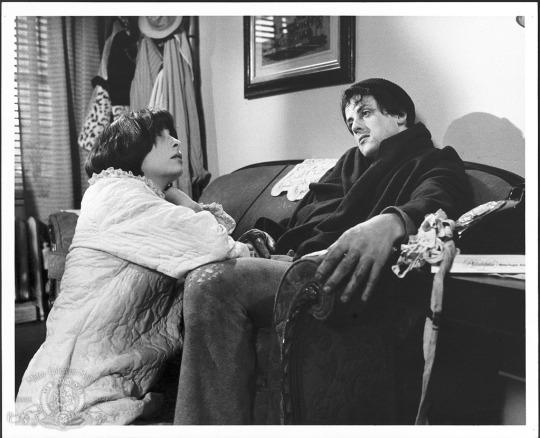

Performance Portfolio: Sylvester Stallone and Rocky

The story of 1977’s Best Picture winner, Rocky, was a rags-to-riches story both in-universe, and out, especially where it’s star was concerned.

Rocky tells the story of Rocky Balboa, a down-on-his-luck prize-fighter who ends up lucking out with the chance of a lifetime: fight the heavyweight champion of the world. In a classic underdog story, Rocky follows the boxer as he seizes his chance to gain self-respect, fighting for a better life and a chance to prove that he’s got what it takes to stand in the ring with the best.

And behind the scenes, Rocky was the story of a down-on-his-luck actor, who wrote a screenplay in three and a half days, submitted it to be made into a motion picture, and refused to back down from insisting upon playing the lead role, in the smartest decision of his entire career.

It’s not an exaggeration to say that Sylvester Stallone’s biggest Hollywood role, and biggest step of his entire career, came in the film Rocky, directed by John G. Avildsen.

Rocky saw Stallone as the lead, and the most iconic character he’s ever played up until this point. As Rocky Balboa, Stallone perfected an honest grittiness, a genuine lovable underdog that audiences could recognize flaws in, but instantly choose to root for. To quote Roger Ebert’s review of the film:

“His name is Sylvester Stallone, and, yes, in 1976 he did remind me of the young Marlon Brando. How many actors have come and gone and been forgotten who were supposed to be the “new Brando,” while Brando endured? And yet in “Rocky” he provides shivers of recognition reaching back to “A Streetcar Named Desire.” He’s tough, he’s tender, he talks in a growl, and hides behind cruelty and is a champion at heart. “I coulda been a contender,” Brando says in “On the Waterfront.” This movie takes up from there.”

Stallone’s Rocky Balboa character could easily have been played as a stereotype: a dumb brute with a heart of gold who got lucky. However, Stallone brings to the role a level of emotional intelligence, and a broader character than simply a fighter. He is disillusioned, best displayed during conversations with his trainer, Micky Goldsmith. He is a man in love, he is frustrated by the direction his life has taken, and when he has an opportunity to get out, he is afraid. He is awkward, embarrassed by his circumstances but not by his personality. He is good to almost everyone he meets, and yet we meet him as reluctant muscle for a loan shark. He’s tough, yes, but there is an incredible gentleness underneath.

Although this is the first role that Stallone would come to be known for, it’s interesting that Rocky Balboa stands mostly alone, among the many gritty, brutal action-heroes that Stallone would go on to portray. This is no John Rambo, Marion Cobretti or John Spartan. There is no ‘killer instinct’ or brutality to this character, ironic for the trade he’s in.

While the other characters reached a point, whether in pop culture or in the script themselves, as being boiled down to their ‘job’, or role in the script (cops, soldiers, action-heroes), Rocky Balboa stands as a person, a character. One of the most beloved characters in film history, in fact. For a man who would go on to be known for mostly playing hardened action-men, Stallone’s first big break comes in a remarkably soft character, a fighter with a heart of gold who is incredibly, heartbreakingly human.

Part of this lies in Stallone’s skill in creating a character who, thanks to both screenplay and performance, appears to have been existing in this world before the movie began, and will continue to exist after. Rocky has already been around for a while, evidenced by the numerous relationships and tics in his character: his religion, his pets (two turtles and a dog), his rubber ball…he’s a fully realized character, complete with history, he has a past…but not much of a future.

Stallone perfectly embodies that: the lived-in qualities of Rocky’s life and the hopelessness of the situation. His performance lays the character bare for the audience, so they can see everything about him and feel for him. It is in this performance that the film hinges: in a world full of sports movies, the only thing that can keep an audience invested in the final inevitable victory is the character who earns it. Within a few short scenes, Stallone’s screenplay and performance convey to the audience instantly, without saying it outright, that this character needs the victory coming to him.

And the thing is, it’s not even a victory.

While we’ll cover more of the actual story and climax of the film itself in a later article, it’s important to note for Rocky’s character, and Stallone’s portrayal of him, that ‘victory’ in Rocky’s case doesn’t mean winning the fight. It means earning self-respect, something that you slowly see Rocky gain as the film progresses. This is what he earns.

And thanks to Stallone’s heartfelt performance, we as an audience want him to earn it. We feel for him, and we want him to win, to pull himself out. Stallone perfectly embodies the sympathetic, rough-around-the-edges underdog type character that he had previously touched on, creating in his performance an iconic film character that the audience feels with and grows with. His performance accomplishes exactly what it’s supposed to: making the audience care for, and believe in, a character who has never existed.

And people believed in him so much that Rocky has become a real person, to the point that his native city still has a statue of him. Stallone’s legacy is most easily seen in Rocky, as this character, a character that, to many people, he will always be. It’s the role that made him a star, a breakout, a juggernaut, long before Rambo, the giant success necessary to launch him onto the career ahead.

Thank you guys so much for reading! If you have something you’d like to add or say, don’t forget that the comment box is always open! I hope to see you all in the next article.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Goonies: Final Thoughts

I first saw The Goonies at the age of nineteen, during my first semester at college, well after the age I should have seen it at. At some point, I realized halfway through the movie that this was really meant for an audience a little younger than I was, but I was far too hooked to care.

As of now, I’ve seen the film six times, and all that’s happened is that I’ve grown to love it more.

I never grew up with The Goonies the way other kids did, but even still, it didn’t take me long to become a fan, and it didn’t take much for me to remain one.

I was first struck by the energy this film has: not just from the actors, but from the atmosphere and story itself. The movie has a magic to it, a pull that drags the audience along for the ride, an adventurous, exciting tone that has viewers, whether children themselves or a bit older, completely entranced. I loved the characters, the sets, the action, the dialogue, the chaotic feeling of seven kids all on an adventure: I loved Sloth and the Fratellis, and the pirate ship, and I can’t think of the movie without smiling. It was no surprise that I wasn’t alone in this.

The primary demographic for this film would seem to be obvious: children. As such, this is a demographic that I missed, being just barely an adult when I was first exposed to it. However, it isn’t just because I ‘missed my window’ that I say that the demographic for The Goonies is far broader than simply the age group it’s about.

Like I’ve said before, this movie is aimed at everyone. Whether it’s kids, who see themselves in the group of ‘rejects’ or adults finding themselves sucked into the adventure, this film has something for everyone (with the exception of little kids), created with the intent to make even adults feel like kids again.

Clearly, it worked.

Audiences adore this movie, from the humor and quotable lines to the memorable action-adventure sequences and the sets, but most of all, for the characters and the heart. It’s a film with a little bit of everything, intended to appeal to a wide variety of people, and it works. There’s a reason this film’s fanbase has only grown in the years since it’s release as a major success. And it makes sense: there’s a lot to love about this movie.

Is it a classic along the same vein as 12 Angry Men or The Wizard of Oz? No. But it is a classic, full of memorable moments that stuck with people for a reason. This movie made an impression on people, and a huge impact in the culture, to the point where people who grew up with it now want their kids to grow up Goonies too.

In the end, The Goonies is a fun, exciting adventure film that has a lot of heart to it, determined to take every audience member along for the ride and make them feel like Goonies too. It’s no Citizen Kane, but it’s not meant to be. It succeeds at exactly what it sets out to do: entertain, excite, and make the audience feel something. It goes above and beyond the bare minimum for a kids’ adventure story, and for that, it will continue to be remembered for years to come.

Personal Stats:

Favorite Character: I’d like to say Mikey, but if I’m going to be honest, probably Mouth. I was a bit too much like him when I was younger.

Favorite Scene: The wishing well sequence.

Favorite Line/Dialogue: “Don’t you realize? The next time you see sky, it’ll be over another town. The next time you take a test, it’ll be in some other school. Our parents, they want the best of stuff for us. But right now, they got to do what’s right for them. Because it’s their time. Their time! Up there! Down here, it’s our time. It’s our time down here. That’s all over the second we ride up Troy’s bucket.”

Movie Ranking: Objective 7 or 8/10. Subjective: 8/10.

Well, that’s the end of our look at The Goonies. Thanks so much for reading! I hope you enjoyed this study, and I’ll see you in the next article.

#The Goonies#The Goonies 1985#1985#80s#Film#Movies#PG#Comedy#Adventure#Family#Sean Astin#Josh Brolin#Jeff Cohen#Corey Feldman#Ke Huy Quan#Kerri Green#Martha Plimpton#Richard Donner

3 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

#The Goonies#The Goonies 1985#1985#80s#Film#Movies#PG#Comedy#Adventure#Family#Sean Astin#Josh Brolin#Jeff Cohen#Corey Feldman#Kerri Green#Martha Plimpton#Ke Huy Quan#Richard Donner

1 note

·

View note

Text

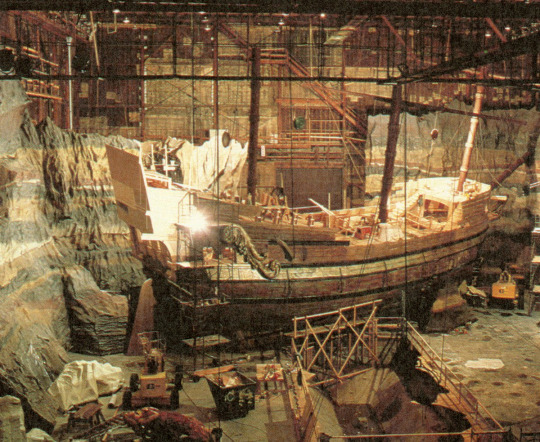

The Goonies: Facets of Filmmaking

From the get go, The Goonies seemed destined for success.

Everything seemed perfectly in place: director Richard Donner (of Superman and The Omen fame) producer Stephen Spielberg (director of Jaws, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, E.T. the Extra Terrestrial, and the Indiana Jones films), screenwriter Chris Columbus, (also worked on Gremlins) and Spielberg’s production company Amblin Entertainment. With all of these talented people, a great script, and a production studio that had a decent record under its belt already, The Goonies was a surefire win.

And a win it was.

But it didn’t come without its challenges.

The film The Goonies was originally conceived by Stephen Spielberg as the basic idea of: “What would bored kids get up to on a rainy day?” After pitching the idea to screenwriter Chris Columbus (who had wrote the script to the film Gremlins, which Spielberg had also produced), the script was written with the obvious conclusion: search for pirate treasure, of course. It was a traditionally Spielbergian ‘high concept’ movie, for sure, but oddly enough, The Goon Kids, as it was then called, didn’t end up a Spielberg film after all.