PhD journey in Emergent Technologies and Media Art Practice (Univ. of Colorado-Boulder), ongoing projects in Chad, Sudan, and Saudi Arabia...and essays along the way

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Photo

You can almost see the music

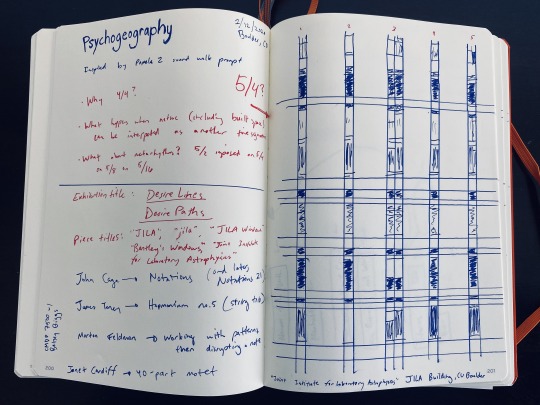

The JILA Building in question for the “Psychogeography” exercise in the previous post. How lucky is it that this long exposure resembles quarter (and maybe eighth) notes??

0 notes

Photo

Listening to a Building that Listens to the Universe

Inspired by a Pamela Z sound walk prompt in the CMDP 7500 week on “Psychogeography,” I translated to paper the prominent features of “columns-like” windows on the side of CU Boulder’s JILA Building (JILA historically stood for Joint Institute for Laboratory Astrophysics and is home today to an array of physical sciences). Interested in whether nature (including built spaces) can be interpreted as a time signature, I imagined the “rows” of the building’s facade as separating different measures of a musical score, and assigned notation to the columns along a musical scale, marking notes manually on Ableton Live according to window shade variations and state of being open or closed, and playing back in various instrumentations. Astrophysicists talk about listening to the universe all the time, but what happens when we listen to their building?

0 notes

Photo

The Mamsha Album

Another project I’ve had in the works but am reimagining this week revolves around the discovery of a photo album in 2015 near one of Jeddah’s pedestrian walkways. The photos, which appear to be from 1998, feature shots of entirely person-less rooms of a house that could be on the market or perhaps vacated and meant to be remembered. Given the push over the last several years to return “residents” to their countries of origin, I imagine this house as one of thousands being abandoned, resold, etc in a massive demographic shift. I ask questions such as: what does it mean to be a resident versus a citizen? Whose future matters most? And why force out someone whose connection to their current home is far stronger than a country of origin they’ve never visited? I am exploring ways to include these photos into a short film.

0 notes

Photo

How an Astrophysicist Can Shake Up Design Thinking: Using a Scientist to Argue an Artist’s Perspective

A discussion surrounding William Gaver’s “What Should We Expect from Research through Design?” (2012) is both timely: there are important questions raised around the framing of design research; and timeless: embodied in the effort to expand our conception of research-through-design is an enduring rift between the arts and the hard sciences, to put it bluntly.

Early on, Gaver hints at a complaint that the diversity of approaches to research through design is seen as a “sign of inadequate standards or a lack of cumulative progress in the field,” arguing that it is instead a necessary facet for generative work. With a particular focus on the area of human-computer interaction (HCI or CHI), Gaver points out that the world of research through design is seen as unorganized, lacking a documented system of precedent and practice. He quotes the following from a panel on “Quality control: A panel on the critique and criticism of design research”: “Research through design, it is said, 'lacks clear expectations and standards for what constitutes "good" design research', and thus would benefit from 'some actionable metrics for bringing rigor in critique of design research'.”

The frustrations seem to emerge from a familiarity with the hard sciences and technical sciences. Whereas the humanities tend to embrace an open discussion on research methods, particularly those concerning generative practices, this is not the case with mechanical engineering, for example, where there would be a well-established history of methods and best practices that any aspiring engineer would need to be familiar with, even if their current method diverged from the precedent. Yet in the relatively more emergent area of HCI, where many designers pride themselves in an interdisciplinary approach including computer science, art, media studies, engineering and even the territories of cognitive science, anthropology, and sociology, it seems a difficult task to establish a rigid form of standards. Rather than view this as an obstacle to generative work, Gaver sees it as necessary:

Overall, I suggest that the design research community should be wary of impulses towards convergence and standardisation, and instead take pride in its aptitude for exploring and speculating, particularising and diversifying, and - especially - its ability to manifest the results in the form of new, conceptually rich artefacts.

This reminds me of a not-so-ordinary example from astrophysics. I’ve taken a couple astrophysics seminars, one a general paper-sharing class and the other a semester-long investigation of exoplanet research, and noticed a couple significant differences in the behavior and practice of astrophysics PhD students compared to those I most often come across in my media arts department: (1) Research is lab-based and includes three to four authors, rather than just one, and (2)There is a strong emphasis on empirical approaches to both knowledge and methods. Essentially, astrophysicists are closely building on the recent work of others in the field, rather than the more dramatic, “creative” departures anticipated in media arts.

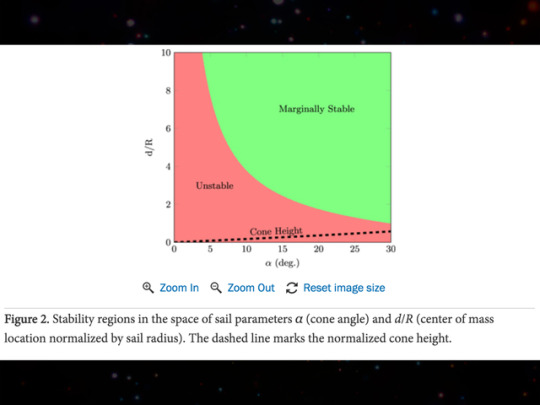

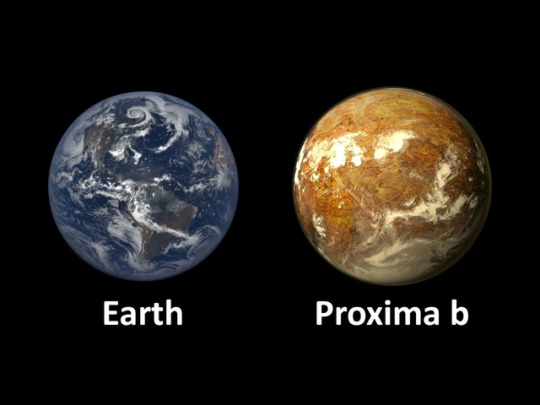

I was reminded, however, of one prominent astrophysicist who stands out as different. The research of Avi Loeb, chair of the astronomy department at Harvard University, is regarded as provocative (to an annoying degree, as the postdoc leading one of our discussions pointed out). Loeb is one of the lead researchers on the Breakthrough Starshot Initiative, a $5+ billion project to send a gram-sized object through interstellar space to Earth’s nearest star (other than the Sun), Proxima Centauri, including a fly-by of Earth-like planet Proxima Centauri b after which the object would transmit information back to Earth. A break from the traditional idea of sending larger spacecraft, manned or unmanned, to the star system, this project’s tiny object would be propelled by laser from the Earth’s surface using light sails. Doing so would allow it to reach relativistic speeds 15-20% the speed of light, reaching the Proxima Centauri system in 20-30 years and sending a message back in an additional four years; for most involved in the project, they would witness a communication from the star system within their lifetime. Given the speculative nature of this project, as well as its radical approach to conventional space vessel size and the overall long scale of time involved for the completion of the mission, Loeb and others may be viewed as “wasting time,” a potential critique of any researcher-by-design not conforming to a set of best practices and convention, as many would have them do.

But Loeb’s provocation doesn’t stop there. There is a strong sense of imagination, perhaps even ludos, in the way Loeb routinely challenges new discoveries in the realm of astrophysics. The recent passage through our solar system of interstellar object Ouomuamua, a cigar-shaped object with properties of an asteroid and a comet, raised many questions about the object’s origin. Loeb famously published a paper speculating that the object was some form of light sail from another civilization.

While Loeb is by no means known as a designer, his playful attitude towards research, which he centers around speculation and the testing of unconventional ideas, seems to be one of the characteristics criticized by those arguing for an adoption of design standards within HCI. Yet many physicists would agree that the energy Loeb’s curiosity injects into the discourse around interstellar travel might be just the sort of thing needed for the next major technical breakthrough.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Are shorts enough? When avant-garde filmmakers have larger audience aspirations

One more installment in the vein of independent filmmaking, manifestos, and carving a career out of a market that does not necessarily represent the type of films one makes.

Dreams of a first feature

When I first met Akosua Adoma Owusu, in the lobby of a hostel in Berlin in 2014, she told me about her plans to shoot a feature film. She was attending Berlinale Talents with a feature script in one of the workshops, and was beginning to navigate the constellation of producers, co-producers, and distributors one almost inevitably needs to pull off an independent feature today (an idea which I explored in my first writing this semester on Med Hondo’s 1979 article “What is the cinema for us?”). As we’ve seen each other once every year or so since then, I’ve been fascinated to hear about the developments with this feature, as I, like many, have aspirations to shoot another feature film and to do so with sufficient production funding and opportunities for international release.

It is freaking tough to fund a feature film

If this was a journalistic article, right about now would be a great place for a nut graf on how, in the independent film industry, it is very difficult to get enough funds together to make a movie, especially a director’s first feature film. On how so many of these filmmakers spend years applying with limited success to grants and residencies that are seen as a gateway to getting the production done. That, to a surprisingly large number of filmmakers who take pride in the “art” element of their films, commercial cinematic release is still viewed as an ultimate space of sharing work with audiences. Short films, to many, are a stepping stone, a space to test out ideas and aesthetics in the hopes that funding could come through for something bigger: a feature. Something the film festivals will pay to fly one in to present. Something that would be of interest to international distributors looking to make a deal that would, for the first time in the filmmaker’s life, pay off the budget they spent making the movie. This money would lead to another, bigger production, and so on. They might not have Avengers-caliber productions in their sights, but they certainly have films such as Moonlight, Birdman, and 12 Years A Slave. After all, these films won Academy Awards while retaining an artistic voice...and made quite a bit of money while doing it.

Wait--does everyone need to make a feature?

So this year, in our most recent meeting, I did not expect to hear that Adoma, for the time being, has put the feature aside in order to focus on short films. She was staying with my family during the Dallas International Film Festival, where we had films in the same Documentary Shorts block. A Film Crew Censors Itself is possibly my most experimental film yet--which doesn’t say much--employing a crude censor block to hide the identities of its characters, all of whom are real people working on a film set in a beach resort north of Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Adoma’s film, Pelourinho: They Don’t Really Care About Us, features voiceover narration of a letter by a frustrated W.E.B. DuBois to the US Embassy in Brazil, and the Embassy’s response, around the issue of Brazil denying stay to black Americans whom it accused of trying to “settle” the country. Adoma cleverly juxtaposes this letter against the backdrop of a festive Pelourinho, the historic center of Salvador de Bahia, adorned with flags and pastel-soaked walls. Pelourinho is also the site of Michael Jackson’s music video “They Don’t Really Care About Us,” pieces of which Adoma hints at towards the end of the film, prior to closing with Pelourinho residents repeating the words of the song in Portuguese. As one after another faces the camera and recites the song’s chorus, “They don’t really care about us,” the audience cannot help but wonder if the experience of DuBois, an outsider, relates in some way to Pelourinho’s own residents.

This film reminded me of Adoma’s past work, careful collages of colorful imagery, patterns, and symbols, occasionally bolstered by a poetic narration. In her film Reluctantly Queer (Berlinale 2016), for example, the camera makes its way pensively throughout its protagonist’s apartment as the character recites, through voiceover, a letter he has written to his mother in Ghana. Through their experimentation with technique, as well as a fondness for veering from traditional narrative, Adoma’s films recall many of the avant-garde works we viewed in our class this semester (one of which, Intermittent Delight, she directed).

Speaking in the car on one of Dallas’s many highways, Adoma pondered whether she would ever make the feature film. After all, short films give her a space to experiment free from the control of producers or external funders. In most cases, she doesn’t need a large team to pull off a short. Some of the works she has made entirely on her own. Many of the obstacles inhibiting her feature project from taking off were posed from within her small network of collaborators.

When we discussed the matter again in front of an audience after one of our screenings, I was surprised to hear that, unlike other friends dead-set on making their first or second feature film, Adoma has for the time being cast the feature film aside completely. She has reached a level of contentment knowing that she’ll continue to make short films.

Can one carve a career out of short films?

I am brainstorming ways one could make a commercially viable career in the world of shorts, and particularly experimental shorts. It’s tough. I imagine that a particularly technical skill or interest could pay off in opportunities to prototype for VR, for example, or animation, but this quickly renders one’s services to others rather than dedicating them to the production of their own art.

Another avenue could be a shift to series, for television or YouTube, perhaps. Yet this almost inevitably requires work in larger teams, something Adoma voiced (and I concur) is not needed or suitable for many projects in the art realm.

There’s the possibility of a successful shorts career through festivals and on Vimeo, although there’s not really any means of making money going those routes.

If one is willing, an experimental shorts filmmaker could craft a career and keep their work artful by shooting high-brow, concept-based ads; such is the case with Steve McQueen, Spike Jonze, and a recent run-in at Dallas IFF this year, Daniel Scheinert. But it’s hard to imagine an experimental filmmaker not voicing frustration over the implications of shooting ads for clients. And, notably, the above names despite their art leanings have all directed widely distributed features already.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Six Questions about Filmmaking in Saudi Arabia

A video of this interview can be viewed at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yYwHo-zkNxI

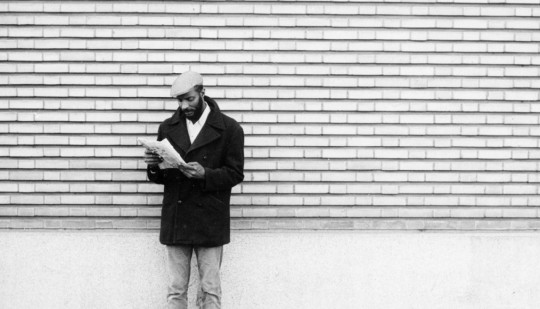

On the subject of manifestos. I met up at IFFRotterdam with Abdulrahman Khawj, a director from Saudi Arabia who is at the epicenter of both the commercial and independent film work emerging after the Kingdom legalized cinema in 2018. For three years, we discussed the possibilities of cinema in a place it was not really permitted, often discussing a manifesto that would seek to document the unique challenges faced by filmmakers in this seemingly insurmountable--and sometimes bizarrely welcoming--filmmaking environment. Abdulrahman’s first feature film, The Great Muse, is the focus of my film, First Feature, which was screening at Rotterdam. Before running to catch our trains on the last day of the festival, we recorded an interview about the current state of filmmaking in Saudi Arabia, as well as our own goals with filmmaking in the next few years, touching on subjects that had served as discussion topics for a possible manifesto: splitting time between ads and shooting features, whether we aim to make films with a possibility of commercial cinema release, and the importance of place for someone looking to write and direct films. Here's the transcript of the interview.

Bentley (B)

First question: Where are the films with stories of people in Saudi Arabia who don't hold Saudi nationality?

Abdulrahman (A)

Where are they? Ok…

Well, even films for Saudi nationals, there's only three of them so far. It's true that Saudi Arabia has a very high diversity of people from different nationalities and backgrounds, and there are some awesome stories. There's a group called Thamaniyah who make documentaries, do you know them? They made two or three short films about the Hajj. Most people in the films are foreigners...or at least from different nationalities. It was really nice.

So there are a lot of great stories out there, but we're still catching up on the Saudi ones. There's a huge potential.

Question for you: I know how you work but others might not know. What keeps you going with a majority of films whose work takes place in post-production.

So you're filming all the time and you wind up with a lot of footage.

B

Just like we're doing right now.

A

Yeah, by 2045 we might see this in a film.

What keeps you patient watching footage and then spending a year or two in editing? Here the whole film takes a year and a half.

B

What keeps me going? It's coffee, of course...espresso.

But what gives me patience? The idea is that I've got a lot of projects going on at the same time. So if I have a project that keeps me in an editing studio for a whole year, I don't feel like it's taking all my time because I'm spread out between other projects, many of which aren't even "documentary" or "non-fiction" in nature, such as dramas. So I'm having fun with some things but concentrating on post-production projects at the same time. Diversity of projects...distractions...just trick yourself, forget you're spending all your time on a film.

Next question: People say "Saudi Arabia's all oil and money" and that it's easy to get funds to make a movie. But maybe in reality it's not. Where do you ideally get your money for making a film in Saudi Arabia?

A

This is a good observation that many people think Saudi Arabia is all money. But those with money are the same, their religion is money. Whether they're in America or Saudi Arabia

or Malaysia or anywhere else, they want something in return for their expenditure, and this is why they might not give out money. There hasn't been cinema in Saudi Arabia until now

so they're starting to envision that movies could earn profit. But even this is tough because there are many things more profitable than films. Individually we make very low-budget, inexpensive films which take a really long time to get any money back. Or we do something where the

director and producer split costs. Savings...you have to save.

B

I feel like in life you have to save. No matter where you're living or what you're working

you have to save money.

A

You have to be smart with money.

We also work commercials and TV in order to earn money to spend on films later. So we work two jobs always.

Next question: What is the end goal for you? We're here, we're struggling, we're trying to make movies, trying to get noticed. Twenty years from now where do you want to be with filmmaking?

B

I'm working on a lot films composed of home video or other types of video not intended to be made into a movie. But the dream in twenty years is that I'd be back in films like Faisal Goes West with more of an imaginative space, addressing contemporary social issues. That's my goal, to get back into drama and comedy and the like. I would have a diversity of projects in form and content.

A

So you won't to go more fiction?

B

It would be spread out...also virtual reality and installation. I've got a project I'm working on now, for example, that is four screens in the same room. But bigger than this, before I die, I want to tell stories...finish telling the stories I've got. Especially the things I witnessed unique to my experience as a kid and teenager in Chad. For example, my relationship with religion, with my parents, such as my father, who was a doctor in Chad. My later work in Saudi Arabia...I want to talk about these stories and get them out to the world. I want them to be public too, not just exclusive to theaters or film festivals.

A

Just like Kamal Jaafari, celebrated films talking about something important and personal but it's for everyone to...

B

Everyone should be able to get something from it.

My third question is: Will you make a commercial film for cinematic release in Saudi Arabia? Or is this not really one of your goals?

A

Yes, but as a producer. There are films for which I'm be a producer and there's films where I'm a director and writer. My directing and writing aren't really for general audiences. They're mostly art films and their audiences are limited. I'm happy with the way things are, but I also want to make films my dad or mom or younger siblings would go watch. That's why I produce, to make films other than those I'd write and direct. I help other people make films. So, hopefully in cinemas soon.

B

You've got the last question.

A

The last question is mine.

B

The last question of yours is for me.

A

It's not as poetic as that.

So now you're studying PhD. You're doing a doctorate in filmmaking and technology...it's very interesting. What are the pluses and minuses?

B

Oh my god that's a big question.

A

Let's just start the whole interview over now.

B

Let's start with the disadvantages. In order to do the PhD--and I still don't know if I'll be spending two years or four years where I'm doing my studies--I had to take myself out of the "Arab World," from Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, and Sudan, Chad, and Africa in general. This hurts a bit. I feel that one of the best ways to spend my youth is to always be moving between Chad, Sudan, America, France, Saudi Arabia and the like. But to concentrate on the PhD I have to spend most of my time in America at the university where I'm studying.

There's many advantages of course. The first is that I'm making even more films now than when I was teaching filmmaking in Jeddah. Teaching six to seven courses a semester didn't allow us to work on our films. Most of the films we made together [in Jeddah] were made in the summer, for example. So now I'm making films inside the program where I'm studying. That's its focus.

The last thing, and this is something you helped me with when I was living in Jeddah--and I hope we keep the communication flowing so we can encourage each other in this--is that I'm challenging myself so that I can develop intellectually. I feel like you could spend your life telling stories, showing us a perspective we wouldn't see if it weren't for movies. And this is very nice, that you could show us a culture or lifestyle we knew nothing about. This is very beautiful. But without a higher thinking, or without pondering the future, or without incorporating a different point of view, or a depth of subject matter--to understand the background elements beyond the story, is very important. So I want to grow intellectually.

A

In filmmaking, the story is a medium for communicating an idea. It's a language--I admire that actually, and I miss it. I'm making movies but I don't have three months, for example, to learn and explore a new perspective.

B

Just look at the films we both enjoy, the director often has a hobby or passion they're crazy about. Perhaps they studied medicine, or architecture such as yourself. Their knowledge of another field made the film's story better, and deeper.

I hope you make it back to Saudi Arabia okay.

A

I'll see you at the next festival.

(Photo credit: Sara Alsubaie)

0 notes

Photo

What is a manifesto for us?

Re-discovering Med Hondo’s “What is the cinema for us?”

A version of this piece was published at Africa is a Country

Deep in the pages of Film Manifestos and Global Cinema Cultures: A Critical Anthology (ed. Scott MacKenzie, 2014) is a 1979 article by France-residing Med Hondo, originally of Mauritania. In “What is the cinema for us?” Hondo unleashes a sharp critique of a global cinema structure in which citizens of non-America/European countries consume those regions’ films with no promise of representation in exchange.

Coincidentally, I came across this article and the multitude of manifestos accompanying it, in a graduate course on the “avant-garde.” MacKenzie writes that “the most prevalent type of film manifesto comes from the cinematic avant-garde [...] calling into being a new future.” Hondo’s piece is by no means avant-garde in style or aesthetic aspiration yet it does call for a new future. Fittingly, MacKenzie writes ahead of Hondo’s piece that “next to the avant-garde, the debates surrounding Third Cinema have produced more manifestos than any other area of the cinema.”

I was reminded of a manifesto I wrote with a colleague five years ago, in 2014, but never published. In “Prospects for a future of film production independent from foreign support,” the outline for which mentions Med Hondo by name although we did not wind up quoting him in the final piece, we argue that the structure of film funding for filmmakers in Africa is overridden by a pseudo-colonial system requiring European, American, or Canadian co-production, to the extent that virtually all projects must enter the cultural language of the granting or co-producing nation, inevitably impacting the filmmaker’s vision and means by which to realize it. Furthermore, the system encourages a reduction of complex, interwoven cultural dynamics down to homogeneous nationalist narratives that strip creative control from the filmmaker.

Forty years after Hondo’s article, still searching for independence

When was the last time you saw an African film? Not a film shot in Africa by an American studio, nor a film outside Africa by a director from an African country, and not the standard: a European co-produced film with an African director but a largely European crew. This week Berlinale hosts the world premiere of Talking About Trees, a film depicting the struggles of four men in Khartoum to re-open the cinema of their childhood. The film is directed by Suhaib Gasmelbari, who was born in Sudan but left for France to study cinema, not unlike Med Hondo, and is listed as a production of Sudan, Germany (co-producer), France (co-producer), Qatar (Doha Film Initiative grant), and Chad, the last of which is due to the partnership of Goï-Goï Productions, the production house of Mahamat Saleh Haroun, also in the ranks of those who left their birth country to study film and media production in France.

Forty years after Hondo’s letter, even the most independent of films from Sudan, the first feature from Sudan on the international festival circuit since 2014’s Beats of the Antonov, relied on the support of production companies in five countries to be made. It’s no wonder that, globally, commercial cinema remains dominated by Hollywood-like industries which still fund their movies “in-house,” even if the old studio system of funding “in-house” has given way to new models such as those of Amazon and Netflix as well as hodgepodge funding from A-list actors as executive producers. Not much has changed, then, since Hondo’s article in 1979:

Throughout the world when people use the term cinema, they all refer more or less consciously to a single cinema, which for more than half a century has been created, produced, industrialised, programmed and then shown on the world’s screens: Euro-American cinema.

Our never-published manifesto from 2014 shares with Hondo a similar disdain for the lack of global representation in global cinema. Adding to Hondo’s analysis is the idea that even independent, international co-productions may run a script and edit through a series of stages qualifying the film for international audiences and potentially restricting the director’s ability to speak from a position of cultural nuance and specificity.

This cinema has gradually imposed itself on a set of dominated peoples. With no means of protecting their own cultures, these peoples have been systematically invaded by diverse, cleverly articulated, cinematographic products. The ideologies of these products never “represent” their personality, their collective or private way of life, their cultural codes, and never reflect even minimally on their specific “art,” way of thinking, or communicating—in a word, their own history . . . their civilization.

This is particularly sad, as many filmmakers will tell you that the most relatable cinema is not muddied down generalities but rather specific, individual stories that give light to shared human lived experience and emotions.

What might a new manifesto address?

“The images this cinema offers systematically exclude the African and the Arab,” Hondo explains, insinuating a link to global politics by those “seeking to maintain the division of the African and Arab peoples—their weakness, submission, servitude, their ignorance of each other and of their own history.” In addition to Hondo’s defense of cinema from Africa and the Arab world, he proposes a system of cooperation between African and Arab cinemas for a stronger dynamic with the system in power: “We need to make a radical change in the relation between the dominant Euro-American production and distribution networks and African and Arab production and distribution, which we must control.”

A possible outgrowth of this mentality might be the system of international co-productions that has come to dominate independent filmmaking today. While I cannot speak from experience beyond the African and Arab filmmaking communities, festival markets and development initiatives within these spaces are often tied to European sources of funding. To receive a Robert Bosch fund for Arab film, for example, the project needs a German production company attached. I have yet to come across a successful, sustainable model of filmmaking that does not involve outside support. Even this year’s Talking About Trees, which offers a strong attempt at Hondo’s vision of pan-African and pan-African cooperation given its production support from Chad, Sudan, and Qatar, was made with the support of French and German co-producers.

A new manifesto might address not only the phenomenon of European co-productions in the space of African and Arab filmmaking but also the acceptance by modern-day directors of this phenomenon as a mal nécessaire that serves as their only path to successful large-scale independent filmmaking.

Lastly, a nuanced approach to hegemonic funding and distribution structures might identify not only Euro-American but also Arab powers as having a commandeering impact on art from Africa and the Arab world. “Arab” is a contentious term that does not reflect the immense diversity of peoples, languages, and cultures from Hondo’s Mauritania across northern Africa to the Arabian Gulf. By no means is the Arab film industry robust, and the Gulf-based non-profit organizations and government funds serving Arab filmmakers do so with good intentions, yet the tendency to solely support “Arab” filmmakers in countries with immense ethnic diversity beyond Arab, a highly politicized identity tied to war in several states, is just as culturally imposing as the Euro-American system about which Hondo wrote four decades ago.

0 notes

Photo

Abstract | Bye Bye Africa: Beyond Chad’s first feature film, to the disidentification of Mahamat Saleh Haroun

An expansion of this piece was published at Africa is a Country

It is a blessing and a curse to bear the title of a country’s “first feature film.” As we saw in the past decade with Haifa Al-Mansour’s Wadjda from Saudi Arabia, a country’s first feature can generate attention and momentum to inspire a future generation of filmmakers. Yet sometimes excitement around a work of “global film” comes at the cost of dismissing its nuance, the sort of reality Gayatri Spivak warns against in “The Politics of Translation,” and which Ngugi Wa Thiong’o poignantly addressed in De-Colonizing the Mind.

Insert Mahamat Saleh Haroun’s Bye Bye Africa, a semi-autobiographical film about an exiled filmmaker returning to his homeland of Chad to make a movie. Bye Bye Africa, which this year celebrates the twentieth anniversary of its release at the 1999 Venice Film Festival, is Chad’s first feature film.

Despite the film’s richness in philosophy, buttressed by Haroun’s careful dialogue as well as his deliberate alternation between Arabic and French, the film has been remembered as simply that: Chad’s first feature film, the one that helped launched Haroun’s career. Extending the work of queer theorist Jose Esteban Muñoz into the realm of national and cultural identity, it is my intent to dig deeper than the film reviews and expose Haroun’s very personal statements of cultural disidentification throughout Bye Bye Africa as he navigates his own complicated relationship to Chad since his exile in France.

0 notes

Photo

Abstract | Skipping the CD: Chadian Music’s Transition from Cassette to Digital

In 2001, I was a teenager in a small desert town in northern Chad, and Aziz Adoum Maryoud’s cassette album Ad-Duud Gargar blazed through town. It was only a matter of time until anyone with a dual-deck cassette boombox was asked to make a copy of the six melancholic tracks, each of which began with flowy verses and finished with a hypnotic repetition of the chorus.

When cassette copying died out in Chad in the 2010s in favor of transferring digital files, most often to USB memory stick or SD card, listeners were presented with a larger library of music at a cheaper cost: “1000 songs for 500 francs ($1).” In the shift, some key ablums in the Chadian archive, Ad-Duud Gargar one of them, disappeared.

The materiality of cassette music, and subsequent skipping of the CD in a transition to digital music, played a role in shaping the popular conscious understanding of what is “Chadian” music in Chad. I also devote time to documenting the archival project of Vik Sohonie, whose archival work in nearby Somalia was nominated for a Grammy this year, to locate, digitize, and publish albums that have fallen to the wayside.

0 notes

Photo

Is “world literature” a useful term?

This week, in addition to selections from Edward Said’s Orientalism as well as work from Stuart Hall, I’m reading Gayatri Spivak’s “Can the Subaltern Speak?” (1983), not long after reading her later article “The Politics of Translation” (1992). Both articles by Spivak lay groundwork for a particular debate in the topic of world literature today; it will be my goal in this paper to briefly illustrate examples before raising a questions related to the framing of “world” literature.

Spivak’s Multilingualism is Inseparable from Her Work

At various points throughout the semester, we have debated whether knowing context about the author of a work hurts or helps us understand their perspective. In some cases, students argue that the act of contextualizing relies on - and conjures up - bias, while others argue that the more one knows about an author, the closer they are to understanding the author’s intentionality. Spivak must certainly be a strong argument for the latter, as she herself cannot separate her commentary from her Indian heritage as well as her multilingualism. At minimum, Spivak is fluent in English, French, Hindi, and Bengali.

Translation is a Launchpad for many of Spivak’s Ideas

Her scholarship includes not just research or commentary but also translation, as she is famous for translating from French Jacques Derrida’s De la grammatologie (and for including a rather lengthy Translator’s Preface on the subject of deconstruction). In “The Politics of Translation,” Spivak introduces readers to the many ethical questions she faces when translating, offering a running commentary of “best practices” of sorts. She recommends only translating when one has achieved a degree of “intimacy” in the language of translation, for example, and that when debating over equivalents between colonial and subaltern languages to imagine whether the author themselves would understand. She challenges simplistic notions of universal solidarity, arguing that “rather than imagining that women automatically have something identifiable in common, why not say […] my first obligation in understanding solidarity is to learn her mother-tongue” (p. 407).

Multiculturalism Lends Fluidity to Her Perspective

In “Can the Subaltern Speak?” Spivak draws on her own multicultural knowledge, acquired through life experience, language and education, in a passage criticizing Michel Foucault and Gilles Deleuze. She notes that their ignoring of the “epistemic violence of imperialism and the international division of labor” is problematic because, she explains, “in France it is impossible to ignore the problem of the tiers monde, the inhabitants of the erstwhile French African colonies” (p. 84). Deleuze “limits his consideration of the Third World to these old local and regional indigenous elite who are, ideally, subaltern,” and Foucault regionalizes power and exploitation without considering the colonial dimension. Spivak does tend to write thoroughly (a critique from Terry Eagleton is that her writing is scattered) but one can only imagine that her fluency in British and French colonialism and postcolonial environments exists on a spectrum with a lesser level of familiarity with other postcolonial environments. Essentially, one can only do so much, and Spivak does quite a job, bolstered by quadrilingual fluency and a comparative knowledge of Indian politics with their own “subalterns,” to borrow a term.

The Problem of “World” Literature

A theme of “Can the Subaltern Speak?” is the inability of Western academia to separate its own narrative from that of an often “otherized” Eastern subject. The work of the subaltern can only be viewed through the lens of the colonial West. This brings to mind a problem with “world literature”: the “world” title, which is applied equally to music and film as well as the literary arts, is generally used to assume any work of a non-English and, some may argue, postcolonial author. Critics have raised the point that the delineation of art into “world” versus English-language is itself a degrading act that enforces a colonial mindset privileging work in the English language over others.

As Spivak concludes, the “subaltern cannot speak,” and particularly the female subaltern, which is subjected to the narratives of a male-dominated system (p. 104). If, thirty-five years after the publishing of Spivak’s article, the very distributors and facilitators of postcolonial art of all sorts promote a system of otherization and linguistic hierarchy, has anything changed?

0 notes

Photo

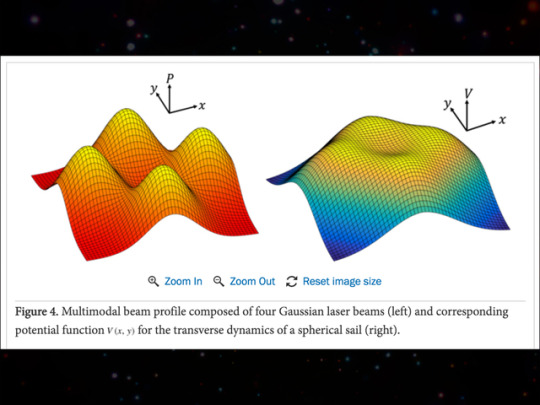

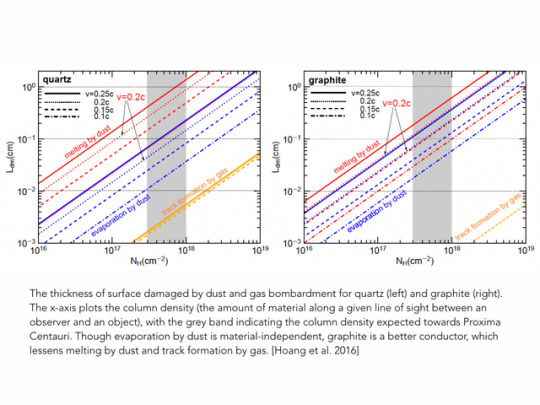

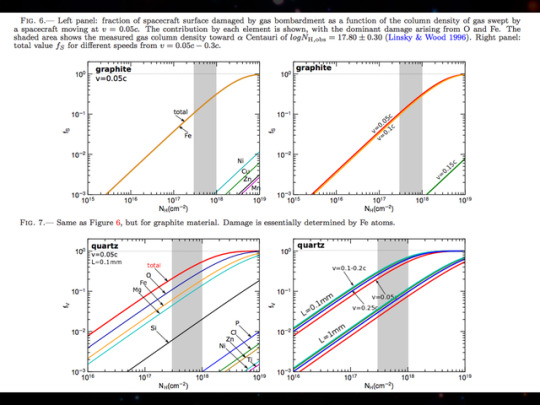

A total mess from my first-ever presentation in astrophysics

Topic was a project to send a “light sail” propelled by earth-based laser, to the nearest star system (Proxima Centauri). The gram-sized object would theoretically reach relativistic speeds, traveling at 1/5 the speed of light, and would shorten our current means of reaching Proxima Centauri from about 45,000 years travel time to...twenty years.

#light sails#CU Boulder#astro#astrophysics#breakthough starshot#space#alpha centauri#proxima centauri

0 notes

Photo

Feminism and Psychoanalysis

Introduction: Envisioning Feminism in Art Discourse

I mentioned Laura Mulvey’s article, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” to a professor last week whose argument against the use of the article I found very interesting. Mulvey’s article, she explained, has been so frequently as a tool to hide actual feminist critique, largely by male professors wishing to show that they’ve “got their bases covered,” that is has lost its stature as an essential text. Immediately I remembered how I had assigned this text for what wound up being one of my final classes in Saudi Arabia. I also thought of how Laura Mulvey may be subject to a dilemma of representation, namely the idea that in an absence of writers of a female identification, there is more pressure on those of female identity and their work is evaluated by questions and standards whose equivalents would almost certainly not be asked of men. But it was not until this week’s readings, particularly the first article by Griselda Pollock, that I have begun to consider further complexities.

The Addition of Women to Art History Changes the Nature of Art History

Pollock opens “Feminist Interventions in the History of Art: An Introduction” pondering the question: “Is adding women to art history the same as producing feminist art history?” It seems to Pollock that the mere act of discussing women in art history is itself a move to address a system structured against the representation of women in discourse. “The structural sexism of most academic disciplines,” she observes, “contributes actively to the production and perpetuation of a gender hierarchy.” The task of “adding” women to art history is not as simple as merely introducing a new topic to an existing field, but rather challenges the way the field has been organized and the way it functions.

Women’s Studies Involves a Restructuring of What and How We Study

Pollock continues to explain that women’s studies is not just a focus on women but on the “social systems and ideological schemata which sustain the domination of men over women within the other mutually inflecting regime of power in the world, namely those of class and […] race.” Pollock then uses examples from Karl Marx and Raymond Williams (p. 3-5) to illustrate an argument that what is actually taking place with the introduction of women’s studies into art history is a shifting of paradigm in which a web (for lack of a better term) of social and economic factors must be considered. Yet she takes it one step further: “Shifting the paradigm of art history involves […] much more than adding new materials - women and their history - to existing categories and methods. It has led to wholly new ways of conceptualizing what it is we study and how we do it.” (p. 5)

Art History Contributes to Sexual Politics and Power Relations

Yet Pollock’s strongest argument - or the one which effected me the most - is page 11, where she explains that “Art history itself is to be understood as a series of representational practices which actively produce definitions of sexual difference and contribute to the present configuration of sexual politics and power relations.” To Pollock, there is no separation of the domain of art history from masculinist practice. The social construction of sexual difference is so innate to art history that there is no separation. Here we might make an extension of one of Mulvey’s key points in “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema”: the psychosexual voyeurism at play in cinema is so engrained that to remove it might be to redefine cinema altogether.

Conclusion: The Transition is Ongoing

In another class this week, we watched The Five Obstructions by Lars Von Trier. Our professor gave a disclaimer that, despite Von Trier’s notoriously sexist and racist comments, the experimental gist of his film should be our focus. Sure enough, our discussion of the film ignored the experimentation and was instead dominated by a commentary on Von Trier’s sexist and racist comments throughout the film. “Am I allowed to hate him?” asked one student.

Inevitably, the restructuring of art commentary will be accompanied by growing pains, even anger. There may very well be professors and students alike who embrace a shallow view of feminist theory as a sort of lip-service. Time will tell how well the academic community will integrate a more in-depth approach to feminist critique.

0 notes

Photo

Semiotics (and teaching in Saudi Arabia)

While teaching the first iteration of a course called “Content and Consciousness” at a women’s university in Saudi Arabia, a student raised her hand during our first discussion on semiotics. “It seems like what these people are writing is common sense. Why do they get credit for these ideas?” This question represented what I hoped would be a core realization for many students: That for factors of language, timing, and gender, the canon of thought in the area of art theory and deconstruction is inhabited largely by men from central Europe, writing in a period stretching back over the past four hundred years.

With Jacques Lacan’s theories of psychoanalysis a close second, Ferdinand de Saussure’s linguistics won the prize among my students for “most-seemingly-obvious-yet-fundamental-observations.” Returning to de Saussure’s work among a collection of texts that reinforce a narrative of de Saussure’s integral role in the development of Structuralist, and later Poststructuralist, thought, I would like to identify and explore a couple of his key observations, proposing an explanation or two for each as to why they were so fundamental.

The Sign, the Signified, and the Signifier

In “Nature of the Linguistic Sign,” from Course in General Linguistics, de Saussure writes that “linguistic unit is a double entity, one formed by the associating of two terms,” both of which are “psychological” and “united in the brain by an associative bond.” He continues, writing that “the linguistic sign unites, not a thing and a name, but a concept and a sound-image.” Important in this process is the recognition that a phoneme refers to speech production, yet de Saussure is interested not as much in the act of speech but in the idea evoked by what he calls “sound-image.” The combination of concept and sound-image de Saussure calls a “sign” [signe], returning to label the concept the “signified” [signifié] and the sound-image the “signifier” [signifiant]. Upon hearing this idea, one can already begin to imagine how influential this would be for later writers, particularly those of the Frankfurt School and, later, Jacques Derrida and the deconstructionists. De Saussure puts into very clear and reproducible terms that the way we understand words is based on contextual, psychological association rather than an unchanging, always-been-that-way inherent meaning.

The Nature of the Sign is Arbitrary

While this terminology would have a very visible and core presence in the works of future writers, and indeed serves as a sort of base point of iteration for theories of Structuralism and Poststructuralism alike (Lacan himself a great example), it is perhaps de Saussure’s next idea that is the most distinct: the nature of the sign is arbitrary. Using the very fact that there are different words to signify the same concept across different languages, de Saussure illustrates that sign of a certain animal, for example, should be signified by one sound-image versus another. Again, de Saussure emphasizes a fundamental point that language is not “given,” its system of signifiers and signified are constructed for a variety of reasons and happenstance, none of which are inherent. This point seems particularly useful not just in the practice of deconstruction but also in construction, that when one seeks to build “reality” or “hyperreality” through their art that they are aware of the flexibilities of interpretation, as well as the freedom of reality construction at their disposal.

Implications for Future Discourse

When my student asked her question, my immediate response was something of a mantra, that these observations seem like obvious common sense to us today, and in many ways it is disheartening that our canon of writers lacks women and particularly those from continents other than Europe. But, just like language, I believe academic discourse is ever-changing—and becoming increasingly global—and it is people like my student in Saudi Arabia who will have the next chance to have their say and introduce the world to new ideas and understandings.

0 notes

Photo

So I’ve started a PhD.

For the longest time I didn’t think I would need/want to do a PhD. Same was the case with my Master’s degree. There are always convenient counter-arguments to furthering your formal education, namely that the educational systems are only somewhat efficient (let’s just say a lot of money is wasted), they tend to be dominated by particular ideologies, and the philosophy that “you don’t need to go to university to learn x subject or skill.” This last point is particularly true in the arts world, where, until recently and with the exception of some European universities as well as those in Australia and New Zealand, there wasn’t even a way to incorporate the scholarly PhD dissertation with practical artistic production and experimentation. This is partly due to the emphasis on the Master of Fine Arts as the terminal degree that would qualify one to teach in the field of arts. Yet, in many if not most countries, government educational ministries, having no prior connection to arts production, still privilege (and often require) the PhD over MFA. This happened to me in Saudi Arabia, where little by little the university where I was teaching began to change out its MFA and MA-holding lecturers (like myself) with people holding PhDs. I survived the cuts but began shifting my focus to PhD programs that would qualify me to teach elsewhere in the future, while allowing me to keep up (and even improve) my practice: making films, music, and interactive narrative. Over a year of applications, and here I am. Back in the USA, a first-year PhD student in Emergent Technologies and Media Art Practice at the mountain-lined campus of the University of Colorado - Boulder.

2 notes

·

View notes