Text

The New PSU Art Museum That No One Asked For

Whether Portland State University students like it or not, Neuberger Hall will be undergoing major renovation over the next couple years. The building’s completion is projected for August 2019, leaving its former academic occupants displaced until then. Some students were not aware of this renovation until only recently, even though the project was publicly announced in late Spring 2017. While students are still relatively in the dark regarding the renovation overall, the inclusion of a new art museum in this project has been a seriously overlooked and forgotten detail.

While announcements of Neuberger Hall’s renovation have kept the addition of an art museum in the project as a side note, it is not an addition that should be downplayed. Upon its completion, the museum will occupy 7,500 square feet between the building’s lower two floors, featuring entrances on both the South Park Blocks and SW Broadway. Admission will be free to students and the public.

The museum will be under the name of Jordan Schnitzer, the real-estate developer and art collector who donated $5 million toward the renovation. Schnitzer’s reputation in the regional art world is seemingly second to none, being that he is one of the largest art patrons in the Pacific Northwest and personally holds a collection of over 10,000 fine art prints. If you aren’t familiar with Jordan Schnitzer, you still may have seen the names of his parents, Harold and Arlene Schnitzer. Among the family’s long history of arts patronage, their names mark the Pacific Northwest College of Art’s main building, the Arlene Schnitzer Concert Hall downtown, and the Arlene Schnitzer Visual Arts Prize offered annually at PSU. Though hailing from a powerful family legacy, Jordan Schnitzer himself has played a significant role in the Northwest’s art culture, having donated or lent artwork to many key art institutions in the area.

If you’ve visited the University of Oregon campus in Eugene, you may also recognize Schnitzer’s name. The Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art is UO’s flagship art center, placed under the name following the museum’s expansion during the 1990s with Schnitzer’s donation.

PSU will not be the second university with a museum Jordan Schnitzer has his name on either. Washington State University in Pullman currently has its art museum under renovation, re-opening this April as yet another Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art. Both museum administrations in Eugene and Pullman have been discussing how they can differentiate from one another and navigate separate publicity.

As if that weren’t enough, Oregon Public Broadcasting reported in June 2017 that Schnitzer is “in talks for a fourth Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art in Corvallis, at Oregon State University”. This means Neuberger Hall will shelter the third of four JSMAs.

Jordan Schnitzer aside, it is difficult to speculate exactly what this new museum will mean for PSU and its students. The museum will be sharing floors with the student service offices on the first floor, also squeezing in with the classrooms and art studios on the second floor. It will be integrated with everyday campus life, not existing as just a solitary entity.

Is this a good thing? Many schools have art museums, so it may only be natural that PSU is trying to follow suit, but students certainly did not ask for one. Though only time will tell, university art museums too often are notorious for ignoring their students.

A university museum is as much an institution as an independent city museum, and its place within a school setting invites another level of bureaucracy. It is an institution inside an institution. This setup positions university museums to function both as their own separately-managed entities and as school-administered organizations.

One of the major necessities for any museum is money to operate, and the approach to funding varies from campus to campus. Some receive much of their money through their respective universities, but many more tend to be primarily reliant on grants and generous patronage. A museum can lose much of its funding if its university faces financial difficulties or has not budgeted properly, leaving them to look to outside communities. A museum would have to operate with grants that require targeting an audience consisting mostly of non-students, and fundraising efforts are directed similarly.

During the June 7, 2017 press conference addressing the Neuberger Hall renovation and JSMA inclusion, the museum’s budget was briefly mentioned. “Included in this gift is an amount to establish a funded endowed museum director position,” said Schnitzer. “We got the university to commit to a budget to operate the museum, so it will be funded and be able to operate”. However, no specifics of that budget were included.

Though the museum and director position were said to be initially paid for, there has been no mention of the long-term sustainability. Even if PSU has agreed to an operational budget, where will that money come from? PSU is showing they have already abandoned the JSMA through this unclear beginning, and as with any campus museum, abandonment by the university always leads to reliance on outside fundraising.

Art museums on college campuses are fundraising machines. Yes, they are spaces for art, but they are also honey to wealthy potential donors. While campus museums sometimes offer free admission, there are normally membership rates identical to city museums. The JSMA in Eugene has its membership ranging from $45 to upwards of $1000, and that’s pretty standard. There are even “patron circles” consisting of the most elite donors who give between $1500 and $5000. While campus museums tend to offer student membership rates that are heavily discounted, it’s the most basic membership. Outside patrons who are willing to pay through the nose are yielded an assortment of perks, of course including an invitation to VIP museum parties.

Because university art museums normally appeal to this crowd, they find themselves competing with city museums. Neuberger Hall is only a short walk from the Portland Art Museum, raising questions of the need for a museum at PSU and how the proximity of the two museums will affect one another. A trend at university museums is a desire for recognition from the larger art world, and it reflects in their programming. A museum could go to great lengths to feature work by majorly popular artists, much like University of Washington’s Henry Art Gallery did in 2016 when it held a massive (and controversial) Paul McCarthy sculpture exhibition.

The new JSMA may challenge PAM, and it will certainly create difficulties for existing art spaces at PSU as well. While the JSMA will essentially be replacing Neuberger Hall’s Autzen Gallery, there are still five other galleries on campus. The student-run Littman and White Galleries in Smith Memorial Student Union will have their decades-old roles as PSU’s core contemporary art galleries placed on the line, and the JSMA’s larger presence is poised to threaten their continued existence.

There is always potential for problems to manifest from university museums. Though this can appear as competitiveness with other art spaces, it’s not always obvious. A museum administration might waste money on over-the-top campaigns or artworks, compromise their budget to host bigger shows, or take advantage of student and non-student employees. The institution-within-an-institution setup does not often yield transparency, keeping internal conflicts and controversy behind closed doors. University museums are well-insulated and shielded by both their institutions and their own reputations as cultural centers. That unique positioning also makes them tough to openly criticize, leaving mistreated employees to risk art world alienation and their careers if they opt to call out an irresponsible or corrupt lead curator/director.

The non-transparent nature of these institutions-within-institutions is primed to spark rumors. The lack of details available regarding the new JSMA have left PSU students with no way to expect what exactly they’re getting when Neuberger Hall eventually re-opens. It has led to speculations based on what little information individual faculty have been able to offer when students ask about the situation.

One such speculation that has been in the air came about after the June 7, 2017 press conference. “[The JSMA] is going to provide, I understand, a recurring point of access to the extraordinary Jordan D. Schnitzer print collection,” said Pat Boas, Director of the School of Art + Design. The vague words were interpreted by some as suggesting Schnitzer’s extensive collection would be partially stored in Neuberger Hall, as storing and maintaining artwork is standard at other university museums.

Upon recent inquiry, the Jordan D. Schnitzer Family Foundation addressed this concern via email. “The Foundation has no operational connection to the museum and therefore will not be storing work from its private collections at the PSU museum,” stated Catherine Malone, the JSFF Collection Manager. “We look forward to collaborating with PSU staff in the future to bring exhibitions from the JSFF collections to the museum on a prearranged basis. Unfortunately we are unable to provide ‘access’ in a broader sense due to privacy, staffing, and insurance concerns.” This clarification did not answer all the remaining questions about the JSMA, but it is reassuring to have at least one speculation dispelled.

Will the museum be a positive or negative addition to PSU? It is hard to say for sure until Neuberger Hall reopens and the museum kicks off, but the minimal details available leave the whole project tasting bad. When it opens, students and faculty need to hold the museum accountable. Negative signs must be recognized and managed in order for it to actually be beneficial to the people paying to attend this institution.

To avoid the downfalls and messy business of other university museums, the JSMA has to steer clear of emulating them. Hosting VIP parties and exclusive events is a sign of catering to wealthy patrons, allowing those with money to sway the path of the museum’s programming away from student interests. Students need to be a priority, not big-name popular artists or sensationalized exhibitions. Student artwork must be given regular space like the Autzen Gallery formerly provided.

The entire PSU student body overall should never see a new museum fee when receiving tuition bills either. The total costs of attending PSU have increased too much to be adding on yet another expense. Since the university claims to have agreed on an operational budget, it should not require an additional charge to students.

To get it right, this new museum will have to value student-oriented programming above all else. School of Art + Design MFA students should be welcomed to display their work, and undergraduate seniors should at least have access to the museum for their thesis exhibitions. An Art + Design faculty biennial exhibition should be hosted by the JSMA as well, especially considering it is common practice at many other university art museums, and it is important for students to be exposed to their own instructors’ work in that type of formal environment.

These requirements have to supplement other shows and programming, of course. What isn’t student or faculty art should be largely experimental. The unique positioning of university museums within their respective institutions primes them for exhibiting material that is out-of-the-box and might be out-of-place at a standard art museum. These shows must facilitate conversation and make radical efforts to engage with non-art students. As a multi-use art center, the JSMA needs to adopt the mindset and operational values of the student-centered art galleries it aims to replace, or any serious care for contemporary art at PSU will fade away.

This new art museum will bring a big change to PSU when it is eventually unveiled. It is set to integrate itself into campus life, which will either be wholesome or detrimental. The fronting of the project by Jordan Schnitzer raises questions of who and what the museum will really be for, and PSU’s release of very few details sustains the uncertainty and skepticism surrounding it. Establishing a university museum may be an invaluable cultural and educational addition to PSU, but it also invites new levels of institutional politics. If the JSMA travels down the wrong path, the result will be a huge waste of money and space at student expense. It would be unwise to underestimate this museum.

0 notes

Text

Controversial art is edgy

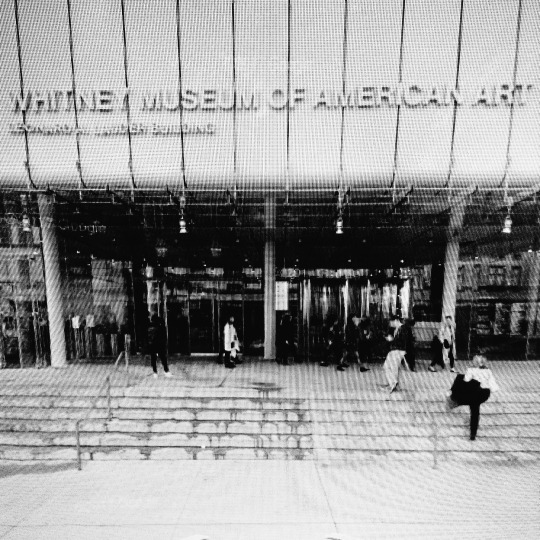

Painter Dana Schutz has made news again after a collective of artists demanded the cancellation of her show now at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston. She caused an uproar during the Whitney Biennial earlier this year, which featured her painting of the dead body of Emmett Till, a young black boy who was lynched in 1955. Many claimed the painting was racially insensitive and perpetuated the fetishization of brutality against black people. Schutz’s show at ICA was recently backed by a letter from 78 members of the National Academy––famous artists like Marina Abramovic, Cindy Sherman, Catherine Opie, and Kara Walker––who stated they “wholeheartedly support cultural institutions like the ICA-Boston who refuse to bow to forces in favor of censorship or quelling dialogue.”

I was following the initial story and backlash online when the Biennial opened, and none of it surprised me. Many people in the lower art world and outside protested the inclusion of Schutz’s painting in the show, while the folks involved in the high art world defended it, (and of course the curators issued a statement of their own to justify themselves.) It didn’t surprise me, because I had already come to expect this type of conflict over “political correctness”, of supposed censorship.

I remember hearing a conversation back at my previous university between one of the head art professors and a high-profile older student; they both asserted that political correctness was ruining art and the art world. I did come to notice that the instructors originally from the east coast were somewhat likelier to be inclined toward this mindset along with the more notorious students in the art department, but it remained a dominant belief overall. These folks painted political correctness as an enemy of the arts, as an annoyance, as something standing in their way. In fact, the most controversial and distasteful material produced by students gained the highest praise by instructors––a testament to the Conceptualism touted by art institutions these days.

It does make sense that art instructors would be pushing such a neoliberal-conservative mode of thinking á la The Atlantic, since the high art world today relies on “incorrectness”. The contemporary art world is one where figures like Damien Hirst reign supreme, held up by immensely expensive projects made purely for shock value and sensationalism, often by means of appropriation, (like a sculpture from this year’s Venice Biennale which took on the image of ancient Nigerian metalwork.) Big-name artists and art executives thrive on controversy, laughing in the faces of their challengers while swimming in millions of dollars in art sales from wealthy patrons. In the Whitney Museum’s case, they appeared to live by “any publicity is good publicity”.

Art institutions continue to push the value of separating oneself from one’s artwork too––in line with how the most famous artists function. Artists can simply claim their harmful work to be “open to interpretation” or “creating conversation” as a way to shield themselves against criticism, and institutions pat them on the back for their edginess.

This dismaying reality only encourages privileged artists to appropriate or demean the experiences of disenfranchised peoples. Controversy brings fame and wealth, and “otherness” is trendy.

It is easy to assume artists are inherently good people, but an artist is just another human, and the high art world is centered solely on making money rather than for the greater good or the benefit of society. The high art world is too often a cesspool of elitism where the wealthiest rule and artists reach the top by crushing their peers who stand in their way.

We forget that artists can be misguided or downright horrible people, even those who claim to be on the side of righteous causes. The high art world enables these types of artists––artists who play the victim and hide behind their institutions or positions of power, redirecting blame toward their critics. Even if she were merely misguided in her painting of Emmett Till, Dana Schutz has still been shielded by the high art world, with other artists and the Whitney Biennial curators claiming her work is a dialogue-starter.

In fact, one of her latest defenders from the National Academy happens to be Kara Walker, a widely-celebrated black artist. Walker’s support has served as further justification for the defense of Schutz; if a black artist is saying it’s okay, then it must be okay, right? It’s no different than saying the Republican party in the United States isn’t racially discriminatory, because Ben Carson is a Republican.

I would like to propose a question then: If Schutz appropriating black experiences and their bloody history is okay, why not display her work in the Museum of African American Art in Los Angeles? If this white woman’s depiction of Emmett Till’s dead body is “dialogue”, then there shouldn’t be a problem with presenting it in a place like the MAAA––a place for exploring the experiences of the African diaspora. Of course I’m only assuming, but that certainly doesn’t seem right to me.

Artists appropriating experiences that are not their own in major institutions is part of why more specific spaces are created––they’ve become necessary. If I want to hear voices of real lived experiences and histories of my own heritage, (as an example,) I have to rely on something like the Contemporary Jewish Museum in San Francisco to give me something accurate. If a non-Jewish person is making work about their perception of the Jewish experience and putting it in a major museum, it skews the audience’s understanding of what those experiences actually are. It’s telling somebody else’s story––my story included.

We don’t put white artists in the MAAA or non-Jewish artists in the CJM, because we understand those places are not for those artists, and that understanding should extend to an artist’s subject matter.

The high art world says there should be no restriction on artists, and I don’t believe there needs to be formal restriction––museums, galleries, and their curators don’t need to incorporate such work into their shows, and artists individually need to know better by now anyway. A rule like that should not be necessary in a civilized society, but as civilization has its informal guidelines, so too should we follow informal guidelines in the art world. It is not censorship; rather, it is decency and respect for the experiences of others.

As for Schutz, I don’t have a good answer for how to deal with that situation, and I’m not in a position to do anything about it directly. It is much more the place of the black art community to propose the proper action in this case, as the issue relates to their experience. However, I don’t believe the high art world will budge at all with this––they will continue to act harmfully and selfishly, as they have.

What we in the lower art world and outside can do is hold one another accountable. Talk to your peers, teach one another, and urge educational institutions to do better. There are substantial possibilities in art creation that don’t involve the infringement of others’ experiences––why not share your own? Artists and art audiences must push to be better and demand better for ourselves and one another. Keep learning, keep growing, and just be a good person.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Art outside the city

The modern city has been the focal point of the contemporary art world. New art spaces are sprouting up like coffee shops, and museums are more popular than ever. Art itself appears to be in high demand these days, especially after seeing the record American auction price recently broken by a Basquiat painting––sold for $110.4 million. The art world is absolutely thriving, even in the midst of government budget proposals suggesting severe cuts to federal arts funding (with the National Endowment for the Arts being the most notable target). The large support and money available for artists and institutions has allowed for massive expansions, residency opportunities, public art, and more.

I had the chance to visit the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art last summer, not long after its recent expansion, and the new building felt like a cathedral. The $305 million addition nearly tripled SFMoMA’s gallery space, then headlining its contemporary-focused top floor with works by famed artists like Jeff Koons and Ai Weiwei. There were visitors young and old, helped along by free admission for kids and teens under 18. Contents aside, it was an exciting experience to visit such an institution dedicated to the arts.

The experience was somewhat of an anomaly for me though; I drove the long seven-hour stretch from San Francisco back to my rural hometown in southern Oregon, where art scenes and museums like those in the Bay area are completely alien. Unlike many of the folks in my region, I’ve been no stranger to art museums; in fact, I’d consider myself rather fortunate to have had the opportunity to see many of the big-name art centers along the west coast from the Seattle Art Museum (SAM) to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) and plenty in-between. Even having had such culturally significant experiences, all have been far beyond my immediate region. I’ve been lucky to have the opportunity to visit a serious art museum maybe once or twice a year.

Growing up back-and-forth between a town with a population of 21,000 and an even smaller rural community of under 1,800 people (where I went to elementary/middle school), I never saw much contemporary art, and serious arts education was limited. There was (and still is) a dedicated art center in town, but it stood on its own and had to meet the needs of the entire area through dedicated volunteerism. With the resources they had to offer, even the smaller grade schools on the outskirts like where I was were able to receive an occasional guest instructor to teach a small painting, drawing, or sculpting workshop, but exposure to more formal visual arts remained minimal.

The rural Oregon community where I spent my pre-high-school years was once primarily reliant on the timber industry; the local mill was immediately across the street from the elementary school, and you could see the big trucks hauling logs from the playground. After Measure 5 (1990) transferred reliance on tax revenues from local school boards to overall state revenue, we lost much of the funding originally from the mill. It was a devastating blow for the school, and the mill finally closed years later while I was in elementary school. Worrying about arts funding becomes trivial when kids are coming to school starving––a direct result of the job scarcity and difficult economic conditions.

With higher rates of poverty than urban neighborhoods, rural communities may be seen as unfit for the arts to thrive in. Rural folks often have less time and money to dedicate to the arts, and inadequate school funding for these neighborhoods results in art programs being the first cuts during educational retrenchments. For too many kids, this means little or no formal arts education; any in-class engagement with the visual arts generally ends after elementary school, even if the local district has access to funding or an arts-savvy volunteer pool at all.

It’s one reason there aren’t many current, rurally-based artists featured in major museums, galleries, and media today. Rural students are not often provided with courses concerning the visual arts, and it isn’t typically presented as a realistic career path. If a program does exist, the curriculum focuses on more traditional art––painters ranging from Monet to Van Gogh are popular in fine art classes––but contemporary art is often only touched on.

The emphasis on traditional art comes from another dilemma of much contemporary art being hard to sell in rural environments. There are several factors as to why that is, again beginning with poverty that doesn’t allow for as much investment in the arts on both individual and community levels. It doesn’t leave a lot of room for expansion; when any money is available for art spending, traditional art is less of a risk to buy or commission. Traditionally-focused arts education then leaves communities expecting traditional media when the arts are available, and a complete exclusion of arts education fosters a further devaluation of anything that isn’t a landscape painting (as an example). It becomes a seemingly unending cycle of no money and little to no arts education that keeps traditional art as the dominant media in rural communities, if a space for art exists at all. Traditional art is what can sell, because it’s what rural art education (or lack thereof) covers, and the education sticks to traditional art, because it’s what sells.

That all said, there are a plethora of artists living and working in these rural communities, far outside urban city centers. Painters, printmakers, ceramicists, sculptors, photographers, and filmmakers are alive and creating in small towns all over the country (and the world), too often unrecognized outside their immediate locations. In fact, some of the most innovative and skilled artists live far from the eyes of city folk.

If you haven’t seen an exhibition outside a major city, (or even just a decently-populated one,) you might not even expect artists to exist elsewhere. This isn’t necessarily the fault of viewers––when visiting any big-name museum or gallery, it can be tough to find rural creatives represented, especially contemporary artists. That does seem to makes sense, as urban institutions will only naturally focus on urban topics and feature artists in those same areas, but it’s not like west coast museums aren’t chock-full of artists from New York City. If art spaces gladly show off artists from other major cities, why can’t rural artists be given more of a platform?

Art spaces in smaller towns and cities can sadly be culprits of this as well. A small art museum might hire on a director from New York who is wanting a break from the big city, and while the hope is to advance the art scenes, it can largely alienate local artists. Spaces formerly used to support artists in the area become playgrounds for big city artists invited in to supposedly bring “culture” to rural and semi-rural communities. While some may argue this brings outside attention to these spaces, the unique contexts of the communities become lost, and the local artists aren’t the ones being celebrated.

It’s no wonder why young artists are leaving the countryside and small towns in droves, all in hopes of a shot at creative success in a big city. Artists are left at the mercy of the city––rather, the city-oriented art market that drives its values into incoming young art students and keeps other rural artists who rely on representation in city galleries as hostages of current trends. An artist from the city might be able to make some work about their own rural experiences, but it has become a rarity to see a rural artist able to share their lived perspectives in any major art space.

Rurally-focused artists haven’t been given serious love since the Regionalist movement of the 1920s and ‘30s, when works like Grant Wood’s American Gothic became symbols of American culture. As modern civilization has revolved more so around the city over the years, artwork from rural foundations have weaned in exposure, and urban-rural tensions seem to have increased significantly.

Rural art and artists have had it rough. Not enough arts funding, not enough art spaces, not enough support from the larger urban art world––not enough opportunity overall––prevents (and discourages) rural artists from sharing their work and experiences. Yet, many rural artists continue to persevere despite what’s against them. Artists young and old are working their butts off to make a living in their communities, yet some of the most inventive, technical, and contemporary art is still outside of major spotlights.

The NEA’s Rural Arts Initiative has been one positive step taken by a major arts organization to lend a hand to students and educators in rural settings. Other rurally-focused educational programs like those headed by museums in Minnesota and North Dakota should be a core effort of institutions big and small. While education is key, so too is providing exhibition opportunities specifically for rural artists both inside and outside cities. Non-city folks deserve to be heard, and it ultimately falls on people desiring to hear their voices in order for change to happen.

0 notes

Text

Where are the art students?

Social media has proven to be a fantastic set of tools for artists in this past decade. I’ve personally grown attached to Instagram, as the image-oriented structure yields a platform prime for arts exploration. I love being able to look into art schools and university art departments around the country, something which normally required travel prior to the Internet’s widespread usage. Connecting with other young creators and students is invaluable; ideas and creative methods can be shared between urban and rural communities, (or rural with rural, urban with urban,) allowing for distance-bridging friendships and mutual corroboration.

Since I’ve been living on my own in a rural southern Oregon town with a (sadly) laughable arts scene, Instagram has been my main link to other working artists. Conversing with students my age living in Oregon’s larger cities has resulted in the exchange of show cards and zines via snail mail, and the positive feedback that comes out of each new relationship only reinforces why we’re all on this career path.

However, building these connections can be difficult when one can’t find others online. When looking for fellow students, our educational institutions are the gatekeepers, since the social media accounts of art schools and universities can be the most direct routes to discovering one another––the youngest, most up-and-coming, emerging artists. Official school accounts have a significantly higher reach than most individuals too, meaning even a single-post promotion of a student’s work may be one of the more supportive and elevating acts an institution can do for someone these days. Even if a school is relatively small, highlighting student artists is a valuable boost, and it ultimately shows that an institution cares and is invested in helping people succeed. Student promotions on college Instagram profiles allow for those outside the institutions or immediate areas to gain some insight as to what these other schools are brewing. It shows what sorts of artwork are being produced and sometimes gives a preview of what styles or methods one would expect to be geared toward while attending, (or perhaps what programs are more popular).

It is fascinating then that many schools don’t promote their younger students. When students are shown off, they will almost exclusively be MFA candidates, (graduate students,) while ignoring or obscuring undergraduates. This does vary by school, and some colleges are doing far better than others, but the trend of seeing art department Instagrams with select or no art students is far too concerning to disregard.

I’ve noticed this from numerous colleges in the Pacific Northwest, (being that it’s my most local region,) but in seeking out a number of art schools and departments elsewhere, I’ve seen disheartening similarities. It is somewhat common to find studio-specific accounts managed by students, but they are typically more hidden from standard searches, and most are limited to only a few people working in a single medium, i.e. ceramics or painting. Many of those accounts tend to be abandoned or rarely updated after a while.

University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) is the biggest name on the west coast guilty of this; for example, their Design & Media Arts account (@ucla_dma) features only nine posts in total, last updated nearly three years ago. Their art department’s main account (@uclaarts) remains active, but it focuses most heavily on non-student events and faculty promotion, occasionally showing work by alumni or MFA students, while undergraduates seem to be featured only once in a blue moon. They claim in their bio that the UCLA arts program is the “#1 Public Arts School in the US,” yet there seem to be next to no undergraduate art majors according to their Instagram feed.

Going further north is another example, University of California Berkeley. Their arts department account (@berkeleyartsdesign) is also focused on non-student events, and half the posts serve only as an extension for their art museum, BAMPFA. What hurt me the most was digging around to find the art department geotag, only to find a plethora of students having documented their own work and classes. The art majors at UC Berkeley seem to be wildly active, sharing paintings, ceramic sculptures, colorful installations, illustrations, and even large-scale collaborative murals, all while their school appears to be giving them little to no attention, at least as indicated by their Instagram.

It’s both better and worse in my home state of Oregon. Both Eastern Oregon in La Grande (EOU) and Oregon State in Corvallis (OSU) do show some student art, but nearly all are class projects. While OSU (@oregonstate.art) does attribute the classwork to individual students, EOU (@eou_art) bunches several pieces into single posts, typically excluding the names of students. There is then Southern Oregon (SOU) in Ashland, whose social media management is arguably the messiest on the west coast. Searching for the most straightforward “sou art” leads to an empty account under an official name (@art_souashland), though the art department has a second account with actual content, started just this April. This second account uses a title and acronym completely obscure to someone who hasn’t attended the university, and there is no work by an individual student, (there is a single piece made by a group, but not even at the school itself). Once again, there is more focus on non-student events rather than students, functioning primarily as an extension of the school admissions account.

Why is there little to no focus on art students on these college accounts? Boiling it down, this would indicate either a lack of enrollment in art programs or actual apathy on the part of these art departments, as posting an image to Instagram is––let’s face it––not tough in the slightest. In fact, all these schools have art students. These schools are not unique in their avoidance of their own students; too many colleges across the country, from California to New York, are culprits of keeping their students invisible in an age where visibility comes at the touch of a screen.

It becomes even more shameful when placed in contrast to college art departments that put more thought and effort in their Instagram curation. University of Washington Seattle (UW) is a prime sample of adequate social media management; their Instagram feed (@uwsoa) features student artwork regularly, and it does give undergraduate BFA students some good love, all while incorporating faculty art, alumni features, well-spaced event announcements, and an account takeover by a student every once and a while.

Full-on art schools are also hit-or-miss. The Pacific Northwest College of Art in Portland (PNCA) has one of the most student-oriented approaches on Instagram, with their account (@p_n_c_a) given over to individual students for short periods of time as digital residencies. While this model is fairly experimental, visitors can view the entire spectrum of artwork coming out of PNCA through Instagram, and all student residents of the account are linked back to their own personal accounts, allowing for people to be easily contacted and connected with. Other schools like the Cornish College of the Arts in Seattle have struggled in social media execution. Cornish finally has a visual arts department-specific Instagram account exclusively featuring their BFA students (@art_cornish), but it was only started this last week. Nothing prior.

Why are numerous university art departments with established Instagram presences so uninterested in their undergraduates? Instagram specifically has been out in the world for over six years, so finally hopping on the train at this point is a bit sad, but it is nonetheless needed. For every institution doing a crap job with their social media, there’s another that’s been using it successfully and in full support of their budding art students. Do these department administrations not pay attention to what others are doing well? Are they flat-out opposed to using social media as such? Are they embarrassed by their student body?

These days, plenty hopefuls are risking a lot by seeking a career path in the arts. Wealth can become a cruelly determining factor in acquiring arts jobs, and university tuition prices seriously hurt art students even before wandering into the job desert. Promoting student work is the very least a school can do, and even those small gestures can open up avenues for young artists who are just hoping to be given a chance and be noticed.

My last school’s ignorance of most of its art students left my peers and I in the cold without any real visibility or connection to the outside world. In begging for a change in approach to social media, I was met with uncaring attitudes and a total lack of recognition, even when nearly all of the dedicated, core art majors had transferred away within a year due to dysfunctional relationships with partisan faculty and department administration. In finding the absence of undergraduates in the Instagram posts of other college art departments, I am genuinely concerned that these issues of disconnection are not unique to my previous university.

I implore arts institutions to be generous in providing promotional boosts to students. I praise those like the University of Oregon in Eugene (UO) for finding a solid balance in online presentation. UO (@uoart) is no stranger to problems, but its Instagram serves as a virtually ideal model; students frequently rotate managing the account and can provide real pictures of both people and the artwork they create. They regularly share a balance of classwork, studios, some alumni, and faculty, but they most importantly create a fluid feed between undergraduates and MFA students; they are presented equally side-by-side, never favoring one over the other, and credit is satisfactorily given.

It is through fair and ungrudging reinforcement of young art students through school social media accounts, especially Instagram, which can help bolster better relationships between students and administration. It is vital in the modern age for allowing students to interact with those from outside schools and to be discovered in turn. I know from my own experience on the platform that priceless ties can be fostered between young artists in this way, and it could prove to form bonds between institutions themselves.

We do not deserve to be abandoned by our schools. Please support your art students.

__________

•Give attention to students of all ages, class standings, and working media •Credit individual artwork and link to the artist’s own account •Show studio spaces and classwork, but not as an alternative to more serious student projects •Acknowledge alumni on occasion, as they deserve continued love •Hand off the account to students on a regular basis •An art department account is not an extension of a university museum or school admissions account

0 notes