The title of my blog is a saying of the great Italian historian of Antiquity Arnaldo Momigliano. Its header image is a picture of the statue of Herodotus at the building of Parliament in Vienna. This is the blog of a leftist Greek male with pictures and videos that I like, with takes on history and politics ... and with many posts on Herodotus, the Father of History. My blog-archive of my political interactions on tumblr in the past is thegreekstranger.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Egyptian Green. Views from Egypt with the writing of Amelia Edwards, Herodotus, Catullus, Ancient Coffin Texts & Various other Descriptions, NUMBER 3 OF 24 COPIES SIGNED BY THE ARTIST, Susan Allix, 2005

Susan Allix (born in 1943) is a British artist.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Illustration to Dante’s "Divine Comedy" (Inferno, Canto I) by Gustave Dore, 1857.

669 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hérodote à la Renaissance (Herodotus in the Renaissance)

Susanna Gambino Longo (editor) Hérodote à la Renaissance. Études réunies, Brepols 2012 (languages: French and Italian)

"Le volume aborde sous différents angles la fortune et l’influence de l’œuvre d’Hérodote à la Renaissance, dès sa première réception humaniste et ses traductions, puis l’impact sur l’historiographie renaissante. La représentation des fastes perses et des rites guerriers des Scythes offrent matière première à la narration des historiens, mais c’est surtout dans la confrontation avec Thucydide et sur la fonction émotionnelle du récit historique que se joue la modélisation de l’histoire, à une époque où l’écriture historique implique un choix idéologique précis. De même, la géographie et la cartographie, qui s’élaborent alors au contact de la découverte de nouveaux mondes, restent redevables à l’héritage hérodotéen, ces disciplines ouvrant le vaste champ de l’observation ethnographique qui allait nourrir moralistes et philosophes. Les frontières d’un champ du savoir à un autre sont ténues et cette porosité des discours permet la diffusion des idées et des arguments à des fins que l’ouvrage se propose d’analyser.

Les auteurs: Jean Boulègue, Susanna Gambino Longo, Brigitte Gauvin, Violaine Giacomotto Charra, Jean Eudes Girot, Antonio Guzman Guerra, Alice Lamy, Frank Lestringant, Dennis Looney, Stefano Pagliaroli, Pascal Payen, Luigi Alberto Sanchi, Carlo Varotti"

Susanna Gambino Longo, Director of the Department of Italian of the University 3 of Lyon, France

0 notes

Text

A Terrace in Amalfi in Moonlight (Thomas Fearnley, 1834)

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

Herodotus on the birth, childhood, and ascent to the throne of Cyrus the Great of Persia (from Encyclopaedia Iranica)

"Time before kingship. The historical past takes on clearer outline beginning with the figure of Cyrus the Great. With him the Persians too are introduced into world history. Like the Mede Deioces, Cyrus appears as the founding king, “with whom their history really commences” (Bichler, 2000b, p. 256). At least two traditions are discernible, which conflict with one another. In Herodotus, knowledge of Cyrus’s genealogy comes through only marginally, when his father Cambyses and his grandfather Cyrus [the First] are mentioned (1.111.5). Cyrus’s connection with the house of the Achaemenids, as suggested in the propaganda conceived by Darius I, is hardly recognizable in the Histories (Rollinger, 1998 [1999], pp. 189-99). While this information of Herodotus provides Cyrus’s lineage more historical depth and also the solidity of a royal pedigree, the appearance of Cyrus in the Histories is essentially based on another tradition. This is connected with the broadly sketched childhood story of Cyrus (see generally Van der Veen, 1996, pp. 23-52), which not only shows striking similarities with the old Oriental storytelling tradition (Lewis, 1980; Binder, 1964) but is also based on the concept of a new king destined by divine Providence to step out of the mists of history without showing a royal genealogy. This element is clearly brought out in Herodotus’s report, which particularly emphasizes the comparably low rank of Cambyses, Cyrus’s father (1.107.2).

The decisive event of Cyrus’s presentation is surrounded in the childhood story with legendary occurrences (concerning Herodotus’s sources on this subject, cf. Accame, 1982; Sancisi-Weerdenburg, 1994; Rollinger, 2000b, pp. 100 f.). There are three stages leading Cyrus on the way to the throne. To begin with, two dreams of the Median king Astyages point to future events and to Cyrus’s reign over Asia (1.107.1, 108.1). Both dreams are essential for Herodotus’s historical picture. While the first dream brings about the marriage of Astyages’ daughter Mandana with the Persian Cambyses, a fairly insignificant protagonist, the second dream leads to the decision to kill the child of this marriage (Bichler, 1985b; see also Pelling, 1996). Through Cyrus’s birth Persians and Medes became dynastically related. This was already anticipated by the oracle presented to Croesus, telling him to watch out when a mule (hēmíonos) first ascended the throne of the Medes (1.55.2, 91.5-6), a construct which is probably due to Herodotus’s creative power (Erbse, 1992). The task of eliminating the child Cyrus was given to the Mede Harpagus, but he did not carry it out and initiated a grave complication in the following events by handing over the little boy to the cowherd Mithradates with the instruction to abandon him in the wilderness (1.109 f.). His wife Kyno, whose name Herodotus equates with the Median word spaka—a key point for the conclusion that Median was a distinct language (Schmitt, 2003)—had just had a miscarriage; and she persuaded her husband to raise the child (Burkert, 1972, p. 125; Fehling, 1989, pp. 110 f.). Thus the plan of the tyrant Astyages was doomed to failure, and Cyrus grew up well cared for.

The second stage in the future king’s ascent was young Cyrus’s role in a game with his companions, who elected him as their king. The young lad proved himself as a sovereign, not only by organizing a royal household with various tasks, but also by treating disobedience with severe punishments, one of the victims of which was the son of the Mede Artembares (1.114). Through his father’s complaint, the matter came to the ears of Astyages, who had the young king led to him and recognized him as his grandson, whom he had presumed to be dead. This led to the punishment of Harpagus, whose son was served to him at a feast (in the manner of Atreus’s punishment of his brother in Greek tradition). It also led to a fatal mistake of the Magi (1.117-19), who considered the danger as averted, Cyrus having been elected as king in a childish game and the oracle having been realized (1.120).

The final stage shows Cyrus’s bid for the throne with the energetic help of Harpagus, who was seeking vengeance. Cyrus offered the Persians freedom from the Median yoke (1.126.5), as well as certainty of guidance by divine Tyche (1.126.6). Finally, Astyages was defeated by his grandson, and as a result the Persians rose to become the rulers of the empire of the Medes (1.128 f.). The sovereignty of the Medes over Asia is described by Herodotus in imperial dimensions. Only a few passages show that there are also other political entities to account for. Herodotus indeed only mentions one specific border of this “Imperium,” one which at the same time divided upper from lower Asia—the Halys River (Rollinger, 2003). With his victory over Astyages, Cyrus had risen to be the ruler of this empire and hence also the lord over upper Asia. But this was merely the beginning of a mighty phase of expansion, which brought this king to the fore as the first person to rule over all Asia (Wiesehöfer, 1987). These conquests are described by Herodotus in three separate sections."

From the article of Robert Rollinger "Herodotus iv. Cyrus according to Herodotus", Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. XII, Fasc. 3, pp. 260-262, available on the net on:

1 note

·

View note

Video

youtube

Iran. Chest-beating and singing during Muharram, the first month of the Islamic calendar, in which takes place the mourning of Shia Muslims for the martyrdom of Imam Husayn Ibn Ali, grandson of Prophet Muhammad and third Shia Imam, near the city of Karbala of Iraq, with as climax the Day of Ashura (the tenth day of the month of Muharram).

From the youtube channel of Jessica Muddit ( https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCfJZdxhU4H1Wn8MMpV4CD_g )

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

King Astyages sends his general Harpagus to kill the baby Cyrus (Herodotus I.108)

Jean Charles Nicaise Perrin (1754-1831) Cyrus and Astyages

An episode from Book I of Herodotus' Histories: king Astyages of Media sends his general Harpagus to kill the baby Cyrus (his own grandson), the future Cyrus the Great of Persia.

I found this picture on https://waterbloggedbooks.wordpress.com/2016/10/13/read-best-stories-of-herodotus/

0 notes

Photo

One of my most favorite exhibits of the Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki, medallion of goddess Athena, 2nd century B.C. I love the 3D effect of it, plus the details, very impressive.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Arnold Heim

Mediterranean Sea, Time of recording at 5.45 p.m., 11.02.1915

Atlantic, Time of recording at 5.30 p.m., 16.02.1915

194 notes

·

View notes

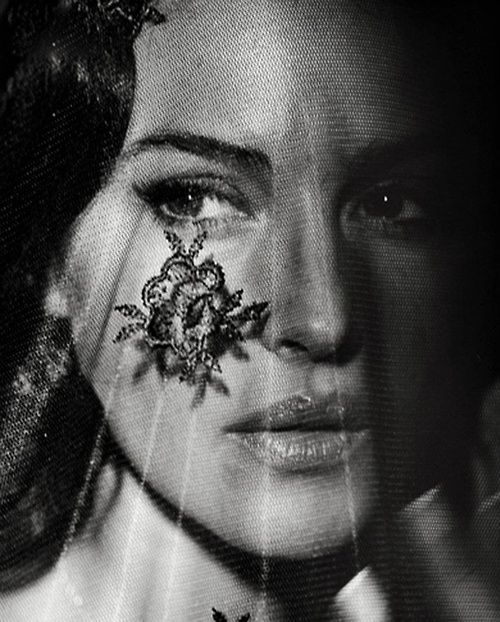

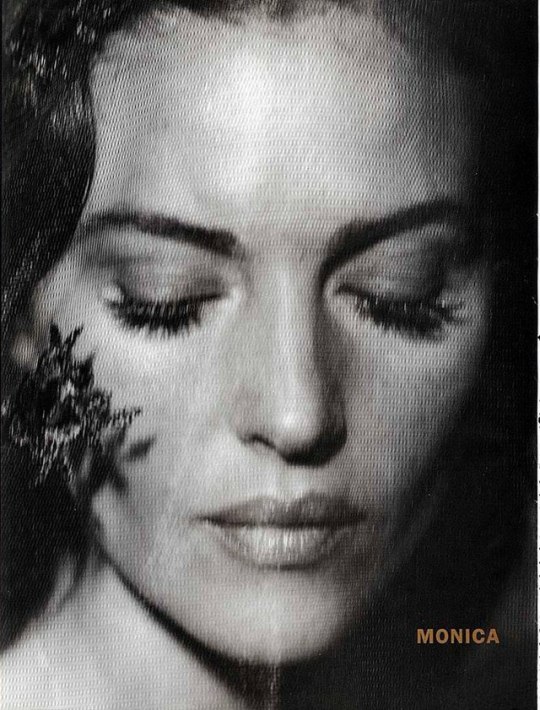

Photo

Monica Bellucci by Gianpaolo Barbieri

14K notes

·

View notes

Text

Title: Penelope Unraveling Her Work at Night Artist: Dora Wheeler Keith (American, 1856-1940) Date: 1886 Genre: mythological art Medium: silk embroidered with silk thread Dimensions: 114.3 cm (45 in) high x 172.7 cm (68 in) wide Location: Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY, USA

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

Portrait of Sappho, fresco from Pompeii

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Herodotus I.114: A Greek Re-telling of an Ancient Iranian Tale?

Two authors from two different worlds and in two different eras recount a similar tale about a role-playing “king-minister-thief” game of children happening in two divergent contexts; one is Herodotus of Halicarnassus in his Ἱστορίαι (I.114) and the other is Menhāj-al-Din Serāj Jowzjāni in his Ṭabaqāt-e Nāṣeri (al-ṭabaqa al-thāmina). What links these two stories (in fact two variants of the same tale) to each other? The present work attempts to respond this question.

Mehrdad Malekzadeh Herodotus I.114: A Greek Re-telling of an Ancient Iranian Tale, Monographs of Median Studies, Tehran 2020.

Unfortunately, as it seems there is not a full version of this paper in English available on the net. It seems that only the Persian text can be found.

Mehrdad Malekzadeh is Iranian archaeologist and historian.

0 notes

Text

Rosalind Thomas on Herodotus in Context

youtube

In this final talk from the spring/summer 2025 edition of the Herodotus Helpline, Professor Rosalind Thomas (Balliol College, Oxford) reflects on her hugely influential 2000 monograph, Herodotus in Context: Ethnography, Science, and the Art of Persuasion. As part of the discussion, Professor Thomas considers the intellectual context for the book.

Indeed, Pr. Rosalind Thomas' Herodotus in Context: Ethnography, Science and the Art of Persuasion, Cambridge University Press, 2000, was a milestone in the Herodotean studies.

0 notes

Text

The Canon of Medicine of Ibn Sina (Avicenna)

Illuminated opening of the first book of the Kitab al-Qanun fi al-tibb (The Canon on Medicine) by Ibn Sina. Undated, probably Iran, beginning of 15th century.

First page of the Latin translation of the Canon: Liber Canonis, de Medicinis Cordialibus et Cantica, iam olim quidem a Gerardo Carmonensi ex arabico in latinum conversa

Source: https://muslimheritage.com/ibn-sinas-the-canon-of-medicine/

The Canon of Medicine (Kitab al-Qanun fi al-tibb) of Abu Ali al-Husayn bin Abdallah Ibn Sina (Avicenna) was a reference for several centuries for physicians in both the Muslim East and the Christian West.

But of course, besides being the best physician of his age, the Iranian Ibn Sina, widely known as al-Sheikh al-Rais (Leader among the wise men), was above all the greatest and the most influential among the falasifah, the Aristotelian-Neoplatonist Muslim philosophers. I think that from this category of thinkers only Al-Farabi and Ibn Rushd (Averroes) could be compared to him; moreover, Ibn Sina's influence was very important even on thinkers who were critical toward aspects of his Peripateticism, like the major "Illuminationist" Iranian philosopher Yahia Suhrawardi.

The philosophical legacy of Ibn Sina is still today alive and source of inspiration in Iran and other countries of the Muslim world.

7 notes

·

View notes