Communicator for schools and nonprofits. Currently the managing editor for Mills (College) Quarterly in Oakland, Calif.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Safe Haven

On December 8, 1941—the day after “a date which will live in infamy”—then-president Aurelia Henry Reinhardt wrote a letter to all Mills families. With the hindsight of nearly 80 years, it’s a surreal read; the main point of the letter was not to offer solace or organize war efforts, but to reassure parents that the Mills campus was unlikely to face any danger from a Japanese attack. “The English Channel is 26 miles wide; New York is 3,500 miles from Europe; California is 5,500 miles from Japan and 2,500 miles from our nearest possession in the Hawaiian group,” she wrote. “May I assure you that there exists no reason to change in any way the schedule and curriculum of this college in the spring term which begins Monday, January 5.”

At that point, no one knew that many students of Japanese descent would soon opt to leave Mills, hoping to avoid separation from their families as they were forced into internment camps across the United States. In the years leading up to World War II, President Reinhardt had approached a number of European artists and intellectuals to offer them a place at Mills as the Third Reich marched across the continent and sent to concentration camps anyone it deemed a threat, including Darius Milhaud and other notable figures in the College’s history, but that welcoming spirit couldn’t protect some of her own students.

When it comes to political and cultural forces outside the campus gates, the College has historically been limited in what it can do to protect its students. But as an institution, Mills has long welcomed members of marginalized communities, and outside restrictions have not altered the campus culture of acceptance.

In recent years, the term “sanctuary” has become a buzzword in our charged political environment. But in a historical sense, the concept originated with the sacred. In ancient Greece, spaces that honored the gods provided some measure of immunity to individuals escaping laws of the state (with limited success), and in Rome, Romulus established a zone on Capitoline Hill where asylum seekers from other places could find refuge. For centuries, places of worship have operated as spaces where people could take shelter, and it’s still happening today—churches around the world house migrants seeking to avoid deportation back to war-torn homelands.

The idea of sanctuary gained popularity in the United States in the 1980s when Central Americans began to flee their home countries in the wake of civil unrest, but Mills took on the responsibility of offering it 60 years earlier in the early days of World War II. In the 1961 book Aurelia Henry Reinhardt: Portrait of a Whole Woman, Chaplain George Hedley wrote that President Reinhardt contacted the Emergency Committee in Aid of Displaced German Scholars (later Foreign Scholars) to invite intellectuals to Mills as soon as Hitler took power in Germany in 1933. Hedley noted that legends were told of Reinhardt physically transporting those scholars to campus herself.

A number of professors soon made their way to Oakland, including Alfred Neumeyer, who taught art history and directed what was then the Art Gallery, and the married couple Bernhard Blume and Carlotta Rosenberg. A German playwright, Bernhard headed up the German Department at Mills until 1945, and Rosenberg was a proponent of educating workers and women.

Of course, the most well-known Mills expats were the musician Darius Milhaud and his wife, Madeleine. In speaking with the author Roger Nichols in 1991, Madeleine detailed her family’s reaction when the Nazis entered Paris in June 1940: “We knew… that Milhaud was among the first on a list of intellectuals to be arrested because he was well known in Germany as a Jewish composer, and also because he did not share their right-wing ideals.”

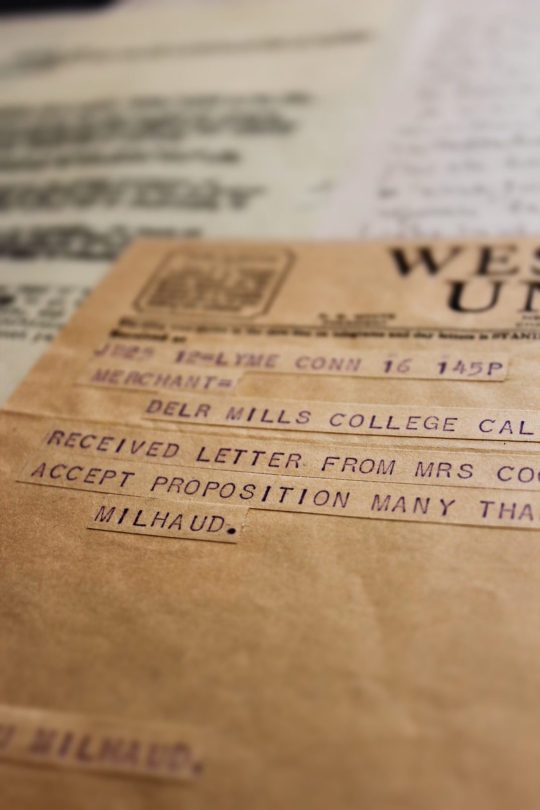

The Milhauds made their way to Lisbon with plans to fly to New York, using an invitation from the Chicago Symphony Orchestra to obtain visas. But upon arrival in Portugal, their plane tickets were declared invalid because they had been bought with French francs. The three—Darius, Madeleine, and their son—were just about to board an American freighter to cross the Atlantic when a telegram arrived with an offer to teach at Mills. The San Francisco-based French conductor Pierre Monteux had contacted President Reinhardt after learning that Milhaud was fleeing to America and connected the two.

Milhaud cabled his acceptance of the position and, a few months after arriving on campus, Dean of Faculty Dean Rusk (later US Secretary of State during the Vietnam War) wrote to the State Department to plead his case for Milhaud’s continued residency in the United States, which hinged on his history of contribution to the arts. Milhaud taught on and off at Mills from 1940 until 1971.

Milhaud’s influence on the Music Department (and the rest of the College) is well known, though he was not the only academic who molded Mills in indelible ways during this time. Helene Mayer, a champion German fencer at the 1928 Olympics, was studying at Scripps College when Hitler rose to power in her home country. She then enrolled at Mills for a master’s in French. While on campus studying for her MA and, later, teaching German literature, she founded the Mills College Fencing Club, jump-starting an organization that lasted for decades. And it’s to the credit of these scholars that the German Department at Mills built a strong enough foundation to eventually send many of its students abroad as Fulbright scholars.

The situation with students of Japanese descent was not nearly as easy to solve, however, with President Franklin D. Roosevelt establishing internment camps less than three months after the Pearl Harbor attack.

Alumnae who were at Mills during the attack remember that day as a sunny one, with word of the incident filtering in as they arrived back in their residence halls after Sunday chapel service. Japanese American students soon found their freedoms curtailed bit by bit, starting with an Army-ordered curfew that restricted their movement even on the Mills campus.

May Ohmura Watanabe ’44, who was born in California to American citizens, wrote about her experiences in multiple issues of the Quarterly. “I remember Dr. Hedley, the chaplain, was very upset and angry. I can still feel his hand tightly holding mine, his body slightly bent forward as he hurried to look at the curfew proclamation posted on the telephone pole just outside the campus,” she wrote in 1985. “He even took me to the Army’s headquarters in San Francisco to protest and to state his disbelief. All in vain.”

Watanabe soon left Mills and returned home to Chico so that she wouldn’t be sent to a different internment camp than her parents and brother. She spent a year at the Tule Lake Relocation Center near the Oregon border, then was released as part of a program allowing some detainees to work or attend school in special approved zones. Watanabe was allowed to transfer her credits to Syracuse University, where she studied nursing. “I remember the special arrangements Mills made for me before evacuation to take my exams in Chico supervised by my high school dean,” she wrote.

The late Grace Fujii Kikuchi ’42 made a similar choice to leave Mills to avoid separation from her family. As a senior, she was more easily able to bring her time at Mills to a close, though it wasn’t a happy time. “My professors at Mills had arranged for me to take my [exam] at a nearby high school,” she wrote in the same Quarterly issue. “All I know is that I was graduated in absentia with my class. Not to be able to attend my commencement after four hard years of work was a bitter disappointment to me.”

The frustrations of the Mills administration during this era were captured in a play by Catherine Ladnier ’70, which she based on actual letters President Reinhardt received from students who left the College due to World War II, including Japanese American students in internment camps. Titled A Future Day of Radiant Peace, the play details the personal turmoil these students experienced as they abandoned their bustling lives at Mills for the uncertainty of the camps. It also demonstrates what little power anyone on campus had to prevent the exodus.

In the aftermath of the war, however, Mills was able to provide sanctuary to several students whose home countries were suffering. Catherine Cambessedes Colburn ’47 and Noramah Sumakno Peksopoetranto ’56 traveled to the College from France and Indonesia, respectively. In the spring 1997 issue of the Quarterly, Colburn wrote about the strangeness of going from a country recovering from war to a land of plenty.

“Mills had sent a list of what I would need, and I owned next to none of the items, nor could I get them. Coupons, given out rarely, were required to buy anything. Besides, the stores were next to empty,” she wrote. “I exchanged my wine ration with a friend for her fabric coupon and my cigarette ration with another for hers, and got enough material for two clothing items.”

Peksopoetranto earned her opportunity to attend Mills through a one-year scholarship from the Edward H. Hazen Foundation. At the end of the year, Dean Anna Hawkes offered her room and board for a bachelor’s degree in education; she spent that summer staying in the home of Librarian Elizabeth Reynolds.

On October 29, 2018—two days after 11 were killed in a shooting at the Tree of Life Synagogue in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania—President Elizabeth L. Hillman sent an email to the Mills community. In it, she harkened back to the College’s history of providing sanctuary to Jewish scholars during World War II and the inspiration they provided to generations of students. “Higher education institutions like Mills have a special role to play in creating and sharing knowledge across boundaries of faith, race, gender, and background,” she wrote. “We can only fulfill our mission when everyone in our community is safe, respected, and able to grow and learn.”

In the last few years, President Hillman has sent a number of similar emails to the campus community after attacks, in the United States and abroad, that have targeted historically marginalized groups. According to Dean of Students Chicora Martin, the typical campus response finds its roots in Mills history. “Whenever an incident happens, we’re among a community where people may not always know what to do, but they are prepared to do something,” they said. “It’s part of our culture.”

“In times of immense crisis and identity-based violence, there is this depth of emotion and despair, but also a desire to be in community,” says Dara Olandt, campus chaplain and director of spiritual and religious life. “It has been very moving for me to see the ways in which students have offered leadership and shown up for each other.”

Olandt attributes the campus-wide attitude of acceptance and protection to the College’s past religiosity—in particular, President Reinhardt was the first woman moderator of the American Unitarian Association. (Olandt herself was ordained by the Unitarian Universalist church.) The chapel “is a refuge, and a place of deep hospitality. That’s what the forebears [who created] this chapel were really about,” Olandt says. “There’s power in this symbolic place where people are welcome in the fullness of their lives, no matter their identities.”

She also counsels those who travel to Mills from outside the country and hail from distinctly different societal and religious backgrounds than their US-born peers. That demographic has naturally been part of the student body for decades, but provides a different set of challenges due to the requirements of F-1 and J-1 student entry visas. Dean Martin serves as the principal designated school official on the Mills campus, so they are the first point of contact for the US government. “Every year, we have someone who can’t make it here because they can’t get a visa,” they say. “There are lots of restrictions with international students, and there’s a lot of documentation that you have to provide just for them to do normal-ish things, like getting a Social Security card or a driver’s license.”

Over the last four years, the legal status of undocumented students has been called into question across the country, and as a Hispanic Serving Institution, Mills has been prompted to respond. Under the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, which began in 2012, undocumented immigrants who arrived in the US before they turned 18 could be granted renewable two-year periods where they would not be deported. When Donald Trump was elected to the presidency, he pledged to end the program—and set off a chain reaction at colleges and universities across the country, which became known as the “sanctuary campus” movement.

On November 16, 2016, President Hillman was one of hundreds of signatories to the Statement in Support of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) Program, which underscored the contributions that its recipients have made to college communities across the country. “America needs talent—and these students, who have been raised and educated in the United States, are already part of our national community,” the statement reads. “They represent what is best about America, and as scholars and leaders they are essential to the future.”

Hillman also joined with more than two dozen college leaders in December 2017 as founding members of the Presidents’ Alliance on Higher Education and Immigration, which advocates for fair treatment of DACA and international students, and she continues to contribute to amicus briefs compiled by the alliance on behalf of DACA students.

In practical terms, Martin says that Mills provides grants to affected DACA students to cover the legal paperwork required to renew their statuses, and the College will provide financial assistance to any undocumented student in the same amount the student would have received from a Pell Grant, which is a federal program and therefore off-limits to non-citizens.

But in terms of sanctuary? If immigration officials asked Mills to turn over student records, the College is theoretically protected by the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA), which prohibits the disclosure of student information, including immigration status, to parties beyond those that need to know for the purposes of that student’s education. Nothing like that has happened yet, but administrators say that it’s really not the point. The last few years have, in the end, cemented the kind of institution Mills wants to be.

“We were asking questions about our own values. The government’s now actively not supporting [these] students, so we have to come out very strongly with concrete statements and actions that clarify for our community where our values lie,” Martin says.

“Aurelia Reinhardt was deeply motivated by her values, which had roots in her religious and spiritual background,” Olandt adds. “She was very much anchored in a spirit of service and what we call today solidarity with marginalized folks. How can we uphold the best of humanity and live a moral and ethical life in the face of challenge?”

1 note

·

View note

Text

Photographed the source image and developed the concept for the resulting illustration on the cover of the spring 2020 issue of Mills Quarterly.

0 notes

Text

Researched a variety of higher ed publication websites before turning to WordPress for the first standalone site for Mills Quarterly, enabling sharing and tagging of individual articles.

0 notes

Video

youtube

Wrote, animated, and provided the voiceover for this video on Understanding by Design, a curriculum-building framework used by Burke’s teachers.

0 notes

Text

Rethinking Diversity: Going Beyond Buzzwords to Make the Best Burke’s

It’s tough for Sheika Luc not to choke up as she recounts her experiences as the first in her family, the daughter of immigrants to the United States, to go to an independent school and then on to college.

When she came to Burke’s as its new Director of Admissions in 2013, she was hopeful that no child would go through those same difficulties here.

“We have this phrase: There are 400 ways to be a Burke’s girl. I think about how we’re doing on that, if it’s actually living and breathing in our classrooms and on the playground,” she says. “We live in San Francisco, and there are millions of ways to tap into diverse ways of thinking and diverse ways of being in the world. We don’t need to search for it — it’s here.”

On the heels of a charged election season, the open embrace of “diversity” can seem like a politically motivated move. But at Burke’s, it’s part of educating our students for the 21st century, where the ability to fully navigate the world (and its broad representation of humanity) around you is essential. Developing those skills, also known as cultural competency, is so vital that it’s codified in Burke’s current Strategic Plan.

The pursuit of a more inclusive and diverse campus is also inspired by what’s best for all Burke’s girls, whether they’re granddaughters of alumnae or from a family that doesn’t speak English at home — or both. Experts say that different perspectives and backgrounds are essential to a vibrant, meaningful classroom environment, and through recent and upcoming work, Burke’s intends to prove that’s the case for all of its students.

“A genuinely diverse and inclusive community is an amazing experience for all 400 girls,” says Head of School Michele Williams. “We’re trying to help girls develop into who they are so they know themselves and, in turn, appreciate and understand the common humanity we share and the strength in our differences.”

Why Diversity Matters

About 40% of Burke’s current student body is comprised of students of color, though true diversity isn’t always accomplished by representation. Luc’s experiences at her New England boarding school underscore the importance of supporting students who may not come from a “traditional” independent school environment, but can thrive just the same. She entered as a freshman and quickly accumulated several negative progress reports in which she was called out for not taking advantage of the school’s resources to better her understanding of the material. “What I find fascinating is that these discussions weren’t being had with me. They were happening about me,” she told a Parents’ Association meeting in January 2015. “They didn’t dig deeper into why I was not empowered to talk to my teachers, advisors, and people at that school.”

Howard McCoy, Burke’s Director of Inclusivity & Community Building, had a similar experience when boarding at a school near Santa Barbara after growing up in Compton. He was the only black student in his class. “I was just supposed to fit in and leave my identity at the door,” he says. “I was always having to deal with becoming more of what they wanted me to be and being less of who I was. Having to navigate those two worlds was very hard.”

At Burke’s, the two bring those backgrounds to their work with the Diversity Task Force, a group of parents, alumnae, and board members that has been examining specific ways to break down those barriers. Both Luc and McCoy were previously classroom teachers — McCoy at Burke’s, and Luc on the East Coast — and saw students who struggled in similar ways. And when a school such at Burke’s pledges to educate girls from all arenas, that’s a real concern.

“Going beyond the obvious in racial diversity, we’re talking about socioeconomics, we’re talking about religion — but really, it’s the diversity of thought,” McCoy says. “We want our students, our families, our faculty and staff to be able to bring their full selves here, whatever that may be.”

These diversity efforts are also intended to create a better classroom environment for all. “Wherever our students are going, we want them to have the tools necessary to navigate the world outside of Burke’s and outside of San Francisco,” McCoy says.

Many studies have been done on the effects of a heterogeneous student body: In the October 2014 issue of Scientific American, author Katherine W. Phillips says this about working with a diverse group of people:

Decades of research by organizational scientists, psychologists, sociologists, economists and demographers show that socially diverse groups (that is, those with a diversity of race, ethnicity, gender and sexual orientation) are more innovative than homogeneous groups.

It seems obvious that a group of people with diverse individual expertise would be better than a homogeneous group at solving complex, nonroutine problems. It is less obvious that social diversity should work in the same way — yet the science shows that it does.

This is not only because people with different backgrounds bring new information. Simply interacting with individuals who are different forces group members to prepare better, to anticipate alternative viewpoints and to expect that reaching consensus will take effort.

Given the kinds of problems that our students will face after they graduate and move on, those that a 21st-century education is designed to solve, knowing how to work with diverse groups and their wide range of ideas could lead to great things.

Beyond that, diverse ways of thinking can be a matter of life and death: In 2011, the University of Virginia’s Center for Applied Biomechanics discovered that women wearing seatbelts had a 47% higher chance of a serious injury in a car accident compared to men wearing seatbelts. The reason why has been attributed to the fact that government crash tests only recently started using smaller-sized “female” dummies.

Or on a smaller scale, as fourth-grade teacher Nayo Brooks stated in her commencement address to the Class of 2016, stepping outside of her own comfort zone to interact with a teacher who didn’t look like her — specifically, the recently retired Laurel Trent — was key to enriching her own experience. “If I had not pushed past my own boundaries to connect with someone who, at first glance, seemed to have nothing in common with me, I would have missed out on one of the most cherished friendships I have ever had,” she said. “We are different in endless ways, but our common joys and pains bring us together.”

Burke’s Multifaceted Legacy

As a school that was specifically founded to educate women to go to college, and in 1908 no less, Burke’s has long been progressive in terms of education. But like many independent schools of its age, the school long had a homogenous student body.In the early years, Katherine Delmar Burke received much support from Sigmund Stern after she tutored his daughter Elise, and many of the families that funded the construction of Burke’s first campus were similarly from Jewish backgrounds.

However, historical interviews with Burke’s alumnae from the 1920s through the 1940s have shown that there was at least a perception that a two-per-class quota system was in place for Jewish applicants.

Many quotas throughout the city faded into obscurity as time marched on through the 1950s and 1960s, though Burke’s student body was still more a reflection of its then-Pacific Heights main campus than the city as a whole. Burke’s first African-American student, Patricia Coleman ’68, was the daughter of local doctor Arthur Coleman, though when she graduated, she was still one of just a handful of students of color.

The school’s relocation from Pacific Heights to its current, more remote Sea Cliff campus helped dispel the notion that Burke’s only catered to that tonier clientele, and the school administration began to make adjustments to welcome a more diverse student body. Budgets for scholarships grew, and more diverse teachers and trustees joined the school. In recognition that more and more families were dual-working households, Burke’s first extended the kindergarten day in the 1970s, and then became the first of the San Francisco independent schools to provide a full after-school program in 1982.

Enrollment increased among students of Asian heritage, though representation among African American and Latino students remained low through the ’80s and ’90s as a reflection of housing demographics in San Francisco — similar to what’s still happening today.

Diversity never faded from the minds of Burke’s administrators throughout those years, with a variety of groups attempting to tackle the problem. A board diversity committee in the 1999-2000 school year conducted a broad survey as part of strategic plan work at that point in time and found that parents generally approved of diversity efforts at Burke’s, though some expressed concern that they could detract from what they considered to be the school’s priorities.

“I’m concerned about becoming ‘politically correct’ at the expense of academic rigor,” said one critic.

However, another said, “The benefit of a more multicultural school is my daughter receiving a wider, more realistic and humanistic world view. She’ll be better prepared for a changing future.”

That’s the same philosophy that’s driving current diversity work: McCoy is in his second year as Burke’s first full-time Director of Inclusion and Community Building, and in that capacity, he supervises workshops for faculty and parents and helps teachers work on creating culturally competent curriculum. He also facilitates the development of affinity groups, which are gatherings of students in accordance with certain demographics with which they identify, including learning differences, blended families, a Gay-Straight Alliance, and race (including a White Ally Group).Despite these actions, however, it became apparent through the most recent strategic-planning process in 2012 that more sustained work was necessary to get Burke’s where it needs to be to provide a cutting-edge education.

The Diversity Task Force

Both Luc and McCoy are optimistic that the newest effort, the Diversity Task Force, will have the legs for long-term change. “This conversation is not necessarily new at Burke’s, but it’s my sense that this is the first time it’s been articulated in this way,” Luc says.

Originally convening in 2014, the Diversity Task Force solicited its members from the parent body through notices in Tuesday Notes, the weekly parent newsletter, and in Parents’ Association meetings. Members of the Board of Trustees, alumnae leaders, and Burke’s staff also participated, along with Alison Park, founder of the diversity thinktank Blink Consulting. However, the intent was not necessarily to stock the ranks of the task force with the most enthusiastic supporters. “We were intentionally not trying to have ‘the choir’ there, because our school is made up of all different people and all different perspectives,” Luc says. “We wanted to make sure that was represented when we’re talking about things that are going to shift and enhance our culture.”

Over the course of about 18 months, the 18-person-strong task force held in-depth meetings and conducted a massive amount of research. Members contacted other schools, companies, parents, and educational organizations to gather information on best practices. “We also clearly identified how we wanted these things to look at Burke’s and not repackage what some other school or group did,” Luc says.

In the end, the task force landed on three solid recommendations, which are now in the process of being implemented (see page 31). Luc says that it’s a real testament to the work of the task force that a number of those originally involved are part of subcommittees that are seeing the recommendations through — what’s now called Diversity Task Force 2.0.

One of those participants is Dana Goldberg ’90, who was a member of the Board of Trustees when the task force was convened and is now a member of the Gender Inclusion Subcommittee. “As an educator, as a Burke’s alum, and —most important — as a human being, I feel it is crucial that our schools think critically and creatively about how to prepare students to live and thrive in this increasingly complex world,” she says. “Ideally, Burke’s should represent the larger community in which its students live — while that is a lofty aspiration, it should be the ultimate goal.”

Goldberg credits her time serving as the chair of the board’s Mission & Accountability Committee with driving home the importance of teaching cultural competency to Burke’s students, and she’s pleased to continue that work on the task force. “The Diversity Task Force has thoughtfully looked at what it means to be a Burke’s girl from a plethora of angles. Although the conversation is just beginning at Burke’s, our school has emerged as a national independent school leader in thinking about this topic,” she says.

Another returning committee member is Jennifer McClanahan-Flint, the current president of the Parents’ Association and former chair of the P.A. Inclusivity & Community Building Committee. “I started this work with Burke’s to ensure that my African-American daughter knew she had a place at the school. I knew that if I wanted her to be in an environment where her job is to concentrate on learning, then my responsibility is to be part of the solution that makes it easier for her to do so,” she says. “However, the work that I do regarding the task force is work on behalf of the school as much as it is my own personal education.”

Like many action items listed under the Strategic Plan, the work regarding diversity isn’t something that will just be checked off and marked as complete. The three recommendations represent just a portion of the discussions undertaken by the Diversity Task Force — after all, what happens if and when the Burke’s student body becomes more reflective of the greater San Francisco population and respectful of everything those students bring to campus?

Luc’s time in a similar school indicates that the sky’s the limit. Instead of concentrating on how to fit in with classmates who are different, a student can concentrate on her work because those differences have already been taken into consideration. “We all go through challenges in adolescence, and we grow and change. Parts of that are just a normal part of a kid growing up, and other parts require support,” she says. “I want us to address and support children in their development so they can learn and all of that other stuff isn’t in the way.”

After all, can you imagine what a Burke’s girl could do if there was nothing in her way?

Three Recommendations

The Diversity Task Force formulated recommendations across three areas in its work to promote diversity and inclusion at Burke’s. They are:

Transportation: In order to make the campus more accessible and bring a wider swath of San Francisco and the Bay Area to Burke’s far-flung campus, the School is investigating how to implement a comprehensive transportation plan that will help both students and staff travel to school — most likely through buses, shuttles and ride-share.

Gender Inclusion: While affirming that Burke’s is a single-gender school and serves girls, there’s also room to recognize that students express their gender identity in a variety of ways. Burke’s will find multiple ways to honor them, including through teacher training, student and parent education, and the avoidance of stereotypes and rigid gender expectations amongst all of Burke’s community members.

Tuition Models: Financial assistance is a necessity in ensuring socio-economic diversity among any student population, and Burke’s is reviewing its tuition model to ensure that the school is reaching and thoughtfully supporting a broad socio-economic range of families.

0 notes

Link

Oversaw the redesign of the Burke’s semiannual magazine, KayDeeBee, for the Fall 2017 issue.

0 notes

Video

youtube

Conceptualized, wrote, shot, and edited the third iteration of the Burke’s Capital Campaign video.

0 notes

Text

You Are All Preachers

What they relayed from their time there was just as eye-opening for the students in the room as it originally was for the conference-goers. Everyone left the Gym that day with these words from St. Mary Therese on their minds: “Be the preacher you are meant to be. Girls, you are going to preach today, and when you do, I hope you own it.”

For 385 teenage girls to hear that they were preachers was undoubtedly confusing, given that preaching tends to be an activity attributed solely to the clergy. But, as the four presenters explained, preaching harks back to the origins of the Dominican Order. It’s also an activity that can be accomplished in any number of ways – and it’s something that anyone can do.

A Gathering of Like Minds

For the past six years, FSHA has sent a student contingent to the Dominican High School Preaching Conference on the campus of Siena Heights University in Adrian, Mich. The conference, which was held this year from June 24-29, brings together high-school students from Dominican institutions in the United States over summer vacation to share and serve in our common tradition.

The FSHA students who attend are selected from those girls on the Campus Ministry Leadership Team (formerly known as the LIFE Team) and the Student Mission Committee. According to Kelley Dawson, FSHA’s previous Campus Minister who chose the three girls, the selection is typically “based on their leadership skills and whether or not the Campus Minister felt that they would be able to put into action what they had gained when they returned.”

Those Tologs who had previously attended always spoke highly of the experience, so when Brikk, Claire and Katherine were asked to go back in March, they were excited at the prospect. “I’d heard about people going every summer, and when they come back, they always had amazing stories to share at the assembly,” Brikk says.

The trip lived up to its reputation, even in the most basic of ways. “Seeing so many Dominican schools from across the country that were so excited about being Dominican, that was really cool,” Brikk said. “Unfortunately, I don’t think I knew about the widespread Dominican community. In my mind, it was just FSHA and La Cañada – the people who go to school here and the Sisters – and that’s it.”

The home states of the other students ranged from Wisconsin and Illinois to Texas, Tennessee and Louisiana. At the liturgy, Claire detailed how she spent the conference’s service day disassembling a chimney for a Habitat for Humanity house with two friends from Illinois and Texas – both named Mike. “We had to fill buckets with bricks that we chiseled off layer by layer, carry the heavy bucket down the stairs and hurl the bricks into the Dumpster – and then do that all over again in the 90-degree Michigan heat with 80-percent humidity,” Claire said. “It was an incredibly rewarding experience, and the three of us felt so proud about what we had done once we finished.”

Other activities included a “saint day,” where professional actors dressed as St. Dominic and St. Catherine of Siena interacted with students at various stations, and presentations on social-justice issues. Katherine attended one on the Dominican presence in Iraq. “I learned about the oppressed women in Iraq and how 43% of Iraqis are under 15 years old,” she said. “This opened my eyes to show me how the Dominican family extends its reach around the world.”

But it was the time spent in the session titled “Preaching Through the Creative Arts” that really started to change the Tologs’ thinking. Participants created rosaries, mandalas, collages, watercolors, even theatrical productions – all of which were dedicated to the idea that preaching doesn’t have to be something that’s spoken. It can be done through actions as well, and it can be done by anyone. “I didn’t know you could preach through the arts and in other ways – I always thought it was the priest who preached the homily at mass,” Katherine said. “I didn’t know normal people could also preach.”

The conference’s other elements began to fall in line with this way of thinking. “The service day is oriented around the idea that service is preaching, helping others is preaching, giving advice to someone is preaching – it’s not just saying, ‘Hey, go follow God,’” Claire said. “My experience at the conference really taught me that living the Dominican way is not as unattainable and difficult as many people may think it is. It is all about the simple actions and choices you make.”

Hearing these sentiments at the Dominican Liturgy delighted President Sr. Carolyn McCormack, who thought the ideas expressed were important for the other students to hear. “I think that we have to define what preaching means. No one likes to be ‘preached at.’ But preaching isn’t always about words; it’s about how we live, how we act toward each other, how we encourage each other to live the Gospel,” she said. “Because that’s Dominic’s calling.”

The Origins of Dominicanism

St. Dominic de Guzman (1172-1221) was the son of a Spanish noble whose path as a theologian took a different turn after he encountered the Albigensians – one group of several that popped up in response to the luxe lifestyle of the clergy in the 13th century. After completing his studies, Dominic joined a community of priests at the Cathedral of Burgo de Osma that followed the Rule of Augustine, and while there, he and his bishop were assigned by Pope Innocent III to preach against the Albigensians in the South of France.

Instead of countering the Albigensians, who were considered heretical, Dominic found himself inspired by their views on apostolic life, where believers lived in accordance with the austerity of the New Testament. Whereas the larger institutions of the Church were seen by a growing number of followers as immoral and materialistic, these new sects emphasized fasting, chastity, poverty and preaching. Dominic spent nine years among them, learning and developing a new vision.

“Dominic, it is clear, possessed a strong instinct for adventure. He was daring both by nature and by grace,” wrote Fr. Paul Murray, O.P., in his 2006 book The New Wine of Dominican Spirituality. “No matter how difficult or unforeseen the challenge of the hour, he was not afraid to take enormous risks for the sake of the Gospel.” And for him, that involved the establishment of a new order whose members more closely resembled the word they were to preach.

Thankfully, the risk paid off – Dominic received the approval of Pope Innocent, and later, Pope Honorius III. All that Pope Innocent asked was for the implementation of an existing Rule of religious life, which Dominic already had in the Rule of Augustine. He also incorporated traditions from the Canons Regular order of the Premonstratensians, which embraced solemn celebrations of Mass and spiritual caregiving of the faithful. Together, that formed an order in which a life of prayer and study led to a ministry of preaching in poverty – the early beginnings of the four Dominican pillars of prayer, study, community and service.

“What was needed, if the truth of God’s word was to be defended, and the Christian vision upheld, was an accurate and profound knowledge of scripture and of church teaching,” Fr. Murray wrote. “And the only way to acquire such knowledge was through rigorous study.”

The early days of Dominic’s work was heavily aligned with female Catholics as well. When he was in the South of France, he organized a group of Albigsensian women to become the first group of Dominican nuns, who lived in accordance with Dominican ideals before the Order of Preachers was formally established. That began a tradition of nuns and Sisters that continues, and at FSHA, to this day.

“Through the years, Sisters have influenced, guided and loved the FSHA girls from 1931 to the present, and there’s something wonderful in that line,” Sr. Carolyn said. “That long line of Dominican women, living a Dominican life, and tending the mission on the Hill. That has an energy."

The energy surrounding the ideas behind the Dominican charism is alive and well on the FSHA campus, but Sr. Carolyn said she is grateful for the words spoken at the liturgy on October 3, which put those ideas into action.

“Charism is the philosophy, the values. Preaching is the fruit of the charism,” Sr. Carolyn said. “You look for ways to do that in your everyday life.”

Preaching at FSHA

That’s exactly what the four conference attendees wanted to drive home for their fellow Tologs when they returned to the Hill. “You can only learn a limited amount from two minutes on the morning announcements or a black-and-white free dress day,” Claire said, referring to other events planned for Veritas Week during that first week of October. “But when you have us, and the students know who were are, they can relate to us better.”

If these three Tologs are demonstrating what it means to preach, then how are they doing it? “For all three of us, being on the Campus Ministry team is a huge way of preaching. Not just through the talks that we give at retreats, but being a presence on campus, showing the girls that it’s OK to be passionate about your faith and want to lead other girls in their faith,” Brikk says. “I feel that’s a big way that I preach.”

“I saw some girls in one of my small (retreat) groups the other day and said hi, so they know that someone knows them on campus,” Claire added. “In a small way, that’s preaching – just a simple hi.”

Of course, for many it can be a big leap to blow up the definition of a word that is so closely affiliated with the practice of faith – for both teenage girls and everyone else. “You don’t need to be a religiously affiliated person; you just need to be a good person and use that goodness inside of you to do something out of the goodness of your heart to help someone else,” Claire said. “It’s about being part of this Dominican community that wants you to go out and do good.”

It’s the action that’s key, the helping of others as a servant of God using the talents and interests that God gave you. “I like that you don’t have to be a good public speaker to be a preacher. You can do it through the arts or theatre – as long as it’s something you’re passionate about,” Katherine said. “If you’re showing others that you’re passionate about it, then you’re preaching.”

In her powerful call to close out the Dominican Liturgy, Sr. Mary Therese gave students a few more specific examples of how they can be preachers: “You preach care when you bring donuts for a friend’s birthday. You preach compassion when you comfort a classmate who is crying. You preach truth when you talk about your hopes and your fears. You are preachers.”

Sr. Mary Therese also recalled when Brikk, Claire and Katherine shared their findings from the Dominican High School Preaching Conference with the Board of Directors before school started. She mentioned how impressed she was with how these three students now embodied the Dominican charism in a real, authentic way that would have left St. Dominic in awe – and in a way that mirrored the setup of the Dominican Order itself. “They didn’t talk about nice experiences and quaint concepts. No longer were prayer and community theoretical concepts, but lived realities,” Sr. Mary Therese said. “No, they preached from the pulpit of their lives.”

0 notes

Photo

Photo of FSHA's Administration Building, now used widely in FSHA publications and as a popular cover photo on school Facebook page.

0 notes

Video

youtube

Conceptualized, shot and edited this stop-motion video to accompany the acceptance package for the Class of 2018.

0 notes

Photo

Spearheaded FSHA's website redesign project. Compiled design proposal using template from Whipple Hill, saw it through appropriate approvals, prepared content for new site, tweaked site and made edits through launch on March 17, 2014.

0 notes

Link

Started FSHA's official Instagram page in October 2012, quickly garnering hundreds of followers.

0 notes

Video

youtube

Conceptualized, shot, "starred" in and provided the voiceover for this infomercial-style video, which advertised the new school community website.

0 notes

Video

youtube

Conceptualized, shot and edited this time-lapse video of a "day in the life" at FSHA over the course of several months, debuting it at the major donors' dinner on May 22, 2013.

0 notes

Photo

Photo of ceramic work from the 2013 Art Show, taken in a room with low diffuse light fixtures and walls of windows on two sides. Used in various school publications.

0 notes