Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Kazuo Shinohara: House Under High Voltage Lines, Tokyo (1981)

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

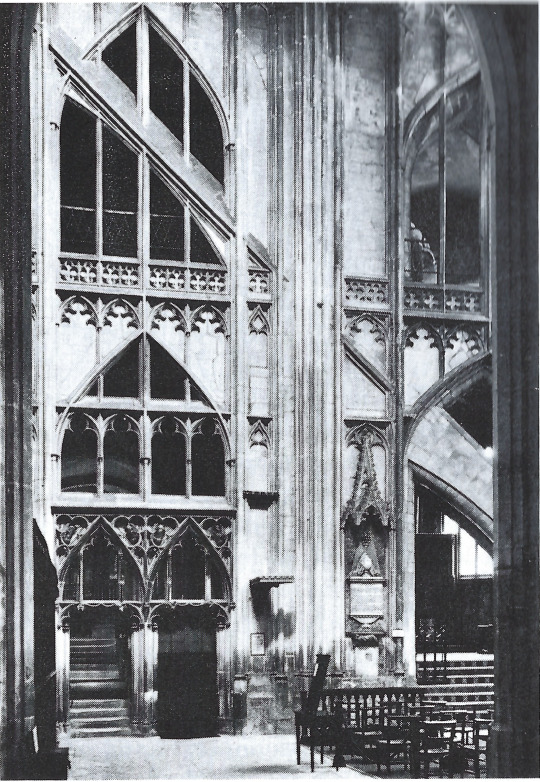

Gloucester Cathedral, 1089-1130 from Complexity and Contradiction (1966) by Robert Venturi

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

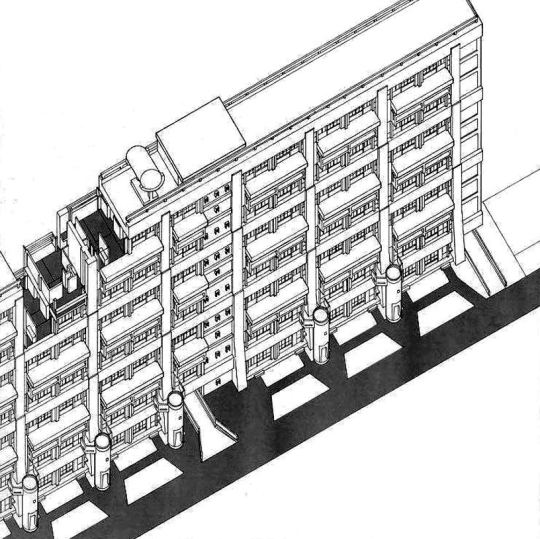

Harumi Apartment House, Tokyo 1958. Arch. Kunio Maekawa.

378 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Harumi Apartment Building (1956-58) in Tokyo, Japan, by Kunio Maekawa

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

Padiglione d'Arte Contemporanea, Milan 1949-53

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Füchtingshof, Lübeck 1655

1 note

·

View note

Text

Arbeitsamt Dessau 1927-29

1 note

·

View note

Text

Gartenstadt Hellerau, Dresden, 1912

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jaques-Dalcroze School of Eurythmics, Hellerau, 1910

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Semper-Oper, Dresden 1871–78

Zweites Dresdner Hoftheaters 1871–78

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Peter Eisenman, House VI, (1972-1975)

Between 1972-1975, Eisenman designed his “House VI” for Mr. and Mrs. Richard Frank (who had great admiration for the architect’s work despite his previously being known as a “paper architect” and theorist.) By giving Eisenman a chance to put his theories to practice, one of the most famous, and difficult, houses in the United States was realized.

Situated on a flat site in Cornwall, Connecticut, House VI stands its own ground as a sculpture in its beautiful surroundings. The design emerged from a conceptual process that began with a grid. Eisenman manipulated the grid so that the house was divided into four sections and when completed the building itself could be a “record of the design process.” Therefore structural elements, were revealed so that the construction process was evident, but not always understood.

Thus, the house became a study between the actual structure and architectural theory. The house was effeciently constructed using a simple post and beam system. However some columns or beams play no structural role and are incorporated to enhance the conceptual design. For example one column in the kitchen hovers over the kitchen table, not even touching the ground! In other spaces, beams meet but do not intersect, creating a cluster of supports. Robert Gutman wrote on the house saying, “most of these columns have no role in supporting the building planes, but are there, like the planes and the slits in the walls and ceilings that represent planes, to mark the geometry and rhythm of Eisenman’s notational system.”

The structure was incorporated into Eisenman’s grid to convey the module that created the interior spaces with a series of planes that slipped through each other. Purposely ignoring the idea of form following function, Eisenman created spaces that were quirky and well-lit, but rather unconventional to live with. He made it difficult for the users so that they would have to grow accustom to the architecture and constantly be aware of it. For instance, in the bedroom there is a glass slot in the center of the wall continuing through the floor that divides the room in half, forcing there to be separate beds on either side of the room so that the couple was forced to sleep apart from each other.

Another curious aspect is an upside down staircase, the element which portrays the axis of the house and is painted red to draw attention. There are also many other difficult aspects that disrupt conventional living, such as the column hanging over the dinner table that separates diners and the single bathroom that is only accessible through a bedroom.

As difficult as the house was to inhabit, Eisenman, the artist, was able to constantly remind the users of the architecture around them and how it affects their lives. He succeeded in building a structure that functioned both as a house and a sculptural work of art, changing the priority of both so that function truly followed form.

459 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mies-van-der-Rohe-Seagram-Building-New-York-1954-1958-Photo-Ezra-Stolle

0 notes

Text

Torre dell'Orologio, Gibellina, Sicilia 1987

0 notes