Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Chasing Provenance by Charlotte Kent

Royalties, digital certificates, provenance. This is the language of modern smart contracts, and it’s being used to rewrite the rules of the art market as we know it.

The past few years of news stories, documentaries and court cases about forgeries and looted art have brought the importance of provenance to a wider audience. The purpose of provenance is not only to assure art audiences that the work was produced by the artist but also that the collector is the rightful owner. Blockchain technology offers to lessen the confusion surrounding authenticity by providing an immutable ledger to record the artwork’s history. It also enables visual artists to share in the profit of their works, sparking fresh debate about resale royalties.

The blockchain ledger can record information, but smart contracts are what enable resale royalties. Smart contracts — code that is executed automatically when certain conditions are met — were initially proposed in 1994 by Nick Szabo as a way of merging e-commerce and contract law using computer protocols that eliminated the need for human intervention. Fast-forward to 2018, and the arrival of ERC-721 on the Ethereum blockchain made possible a unique digital certificate of ownership for a virtual object.

Since digital objects can be posted and reposted, shared and right-click-saved online, the advent of ERC-721 revolutionized the potential of digital art to participate in the art world’s market of scarcity, with the smart contract specifying the sale terms. Blockchain’s record-keeping has also presented a way to publicly disclose a work’s ownership and transaction history. By extension, non-fungible tokens (NFTs) have presented a radical opportunity, but the technology is not fail-proof and frequently reintroduces the need for social and legal contracts, which is precisely what the artist Nancy Baker Cahill showed in her work Contract Killers (2021).

Blockchain’s New Contract

Contract Killers is an augmented-reality work that shows the disintegration of a handshake in front of three symbolic institutions: City Hall in Los Angeles, to represent the failures of civic agreements; the city’s Hall of Justice, to acknowledge judicial miscarriages; and a pile of money, to indicate the “gross inequities of late-stage capitalism.” A fourth hot-pink handshake in front of a gray wall represents the breakdown of social contracts.

The project uses blockchain not only to sell the individual works as NFTs but also to address the rhetoric about disintermediation and transparency surrounding the technology. Accompanying her own smart contract, Baker Cahill included a legal agreement ”intended to be readable and understandable by non-lawyer, NFT purchasers, so that there is no confusion as to intent, application, and scope of the terms.” This is just one of the ways Baker Cahill’s Contract Killers seeks to inject equity and openness into the opaque art market.

Blockchain’s claims to transparency are obviated by the fact that many NFT collectors can’t read code any more than they can understand a legal contract. To be clear: Smart contracts are neither smart nor contracts. They are neither as clearly automated as the word “smart” would suggest, nor are they legally binding contracts. For example, when an NFT is sold on a different platform than the one where it was minted, the automatic royalty doesn’t necessarily work. The claim that “code is law” is common in the blockchain; though it has been espoused since software became common at the turn of the century, the court cases that will determine to what degree that applies are just now emerging.

Though artists, collectors and dealers all want to cultivate trust and a sense of stewardship, articulating precise expectations around what stewardship entails has been rare. Blockchain smart contracts address the power imbalance where artists are expected to accept contracts, not produce them. Patrons in 15th-century Florence produced contracts stating in precise terms what they were funding; even the eccentric English surrealist Edward James had contractual agreements with the artists he supported, like René Magritte and Salvador Dalí.

Now, as artists design a smart contract, they are in a position to stipulate their own expectations, such as a percentage of future sales or a resale timeline. In so doing, they can circumvent the speculative transaction of “flipping,” where a work is bought and typically resold for profit at auction, spiking an artist’s market value in the short term and crippling their long-term growth. Still, smart contracts are dependent on social agreements.

And Baker Cahill’s point is that social dynamics cannot be coded. Blockchain’s premise of a trustless system dangerously ignores the ongoing realities of social relations that are integral to the art market. People buy art as an investment but also because they like it. Collectors frequently want to follow and engage the artist. Such relationships can be supported by legal agreements, but those depend on trust in society and its systems. Contract Killers cleverly uses blockchain to halt overexcited solutionism and insist on repairing our current systems, too.

A Matter of Trust

An artwork’s provenance is partly established by verifying that it came from the artist’s studio or was handled by the artist. Verified provenance not only authenticates an artwork by establishing a historical record of past owners, but increases the work’s value by ensuring authenticity through a careful legacy. As the International Foundation for Art Research (IFAR) says in their Provenance Guide: “The object itself is the most important primary resource and a valuable source of provenance information.” Blockchain’s record of every transaction provides a provenance history, but how can that be ensured when the smart contract comes from the platform? How can the blockchain record be tied to a physical artifact?

The sculptor Hamzat Raheem has an answer. He deployed his own smart contract so that the NFTs he created could act as certificates of title clearly originating from him, just as his marble and plaster sculptures come from his studio, thereby ensuring a clear provenance. He tackles the matter in his project Creative Archaeology (2022), where collectors dig in soil to find one of his sculptures. These are embedded with a near-field communication (NFC) chip. When scanned on a mobile device, the chip activates a private webpage where the finder communicates their wallet address to the artist. Raheem can then send the smart contract that acts as the Certificate of Authenticated Title, developed with intellectual property and arts lawyer Megan Noh. The contract declares that the physical sculpture and certificate, represented by the NFT, must remain united. Transferring one without including the other mutilates the work, according to the contract.

Baker Cahill, Raheem and many other artists are using blockchain and smart contracts to inscribe a new set of social values around collecting art while including legacy practices like legal contracts to support their effort. The royalty approach itself is less important than establishing a relationship of mutual care between artist and collector. And the visual artifact becomes the object representing the importance of that trusting connection.

Media art is often celebrated for its interactivity, and these experimentations with smart contracts reveal blockchain’s ability to alter social relations. Since smart contracts are about encoding events between two parties, these artists push beyond the prescribed contracts of established platforms to explore the potential this technology offers for real social change.

Some galleries have been supportive of the creative prospects inherent to NFTs, especially those representing digital artists. For example, Bitforms Gallery and Postmasters worked with the white-label platform Monegraph to create their own NFT platforms with modifiable smart contracts. The gallerist Magda Sawon of Postmasters has been selling groundbreaking media art as well as physical works for 38 years, and she has recognized that artists are mobilizing blockchain for their creative practice. She and her partner launched PostmastersBC to support artists and collectors, who unlike Raheem may still be new to the technology and need support. The gallery educates the community on blockchain technology as a part of any creative or collecting endeavor.Many in the NFT space have disparaged galleries and curators as gatekeeping intermediaries in sale transactions, but gallerists argue that NFT platforms also charge commissions and “provide spectacularly limited service in maintenance of artwork and career management,” as Sawon decried in an emailed statement. Without that support, artists must marshal their own trajectory while remaining at the mercy of platform protocols.

When a group of crypto artists insisted in 2020 that NFT platforms establish and normalize 10% royalties on resales, the technology’s automation made it an easy ask; though the debate resurfaced when the trading platform Sudoswap didn’t include resale royalties, leading to loud objections by artists who’d already fought this fight. Reflecting on the Contract Killers project a year later, amid the sparring around royalties, Baker Cahill said, “Even standard protocols like that require baseline social agreements. That presumes centralized thought, which is counter to the idolatry of decentralization in the NFT ecosystem.” As the technology develops and expands its reach, differing views around the role of consensus are sure to occur. The flexibility of smart contracts is their creative potential, but their mobilization across cultures will reveal cracks in current social contracts.

Beyond Resale Royalties

The future of blockchain is evolving alongside the artists pushing its boundaries, most notoriously surrounding resale royalties. While actors, writers, graphic designers, and even software engineers have royalty norms in their industries, visual artists have long been disregarded. Blockchain came along and made possible what social and legal efforts had not.

Now artists are presented with a panoply of alternative funding practices beyond royalties. As companies like Masterworks buy art and fractionalize ownership across investors, market regulations and tax obligations appear; Masterworks files paperwork with the SEC before selling shares, an example of how established regulations expand and adapt to new systems. Artists using blockchain have been exploring these avenues since the technology appeared, and they exemplify the most interesting opportunities for long-term profit sharing in an artist’s work.

Simon de la Rouviere’s This Artwork Is Always On Sale (2019) operates according to a novel tax concept, the Common Ownership Self-Assessed Tax (COST) model. COST was conceived by Glen Weyl and Eric Posner in their book, Radical Markets (2018), as an alternative way to conceive of ownership while also enforcing a perpetual payment structure. De la Rouviere took this concept as an opportunity for digital artists to disrupt market practice. The owner of an object — the authors originally provided a case study in real estate — must always list their asking price, and the seller cannot refuse to sell at that price. The set price then becomes the basis for dividend disbursements overtime, which might be paid to an artist for a creative object. De la Rouviere minted and auctioned the conceptual work on March 21, 2019, with a patronage rate of 5%. A new version was created in 2020, and the artist has posted about how others can create their own version. Fractionalized ownership is receiving renewed interest as an opportunity for groups to pool funds and purchase costly goods, like high-end art. The artist Eve Sussman experimented with this formula in 89 Seconds Atomized (2018), a blockchain project based on her short film 89 Seconds at Alcázar (2004), itself inspired by Velásquez’s Las Meninas (1656).

Sussman produced 2,304 NFTs, each corresponding to an “atom” of the 10-minute media work. Though she retained 804 atoms, a full screening requires that all owners agree to contribute their atom at a specified time. Where Masterworks uses this model as an investment fund, artists can pool smaller collectors to support large-scale, or high-priced, projects.

In February 2015, the artist Sarah Meyohas launched Bitchcoin, another model for group support. In her white paper, she explains that each Bitchcoin represents a 5-by-5-inch segment of one of her works. In the original launch, that meant photographs from her Speculations series, which were placed in a bank vault. Possession of 25 Bitchcoins, for a total price of $2,500, provided control over the 625 square inches of one photograph. The owner could then choose to access the physical photograph, or redeem the value for a future print, thereby encouraging collectors to become long-term investors in Meyohas’s work. Predating the launch of Ethereum (and its ability to automate aspects of shared ownership) by five months, Bitchcoin was an early exploration of how artists could finance their practice. The project’s legacy status has contributed to widespread respect for Meyohas, with a new release of Bitchcoins auctioned at Phillips in 2021, fetching up to 10 times the original price per unit.

Bitchcoin represents an early form of what is now described as a social token. Particularly in the music and sports industries, social tokens enable celebrities to tap the support of their fans in order to distance themselves from the demands or limitations imposed by their representation. Creatives promise token owners access to certain events and opportunities, with the coin value increasing alongside the artist’s success. In visual art, these typically operate under the guise of decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs) that can act as trusts, LLCs and community projects; in the United States, the state of Wyoming allowed DAOs to register as LLCs as of July 1, 2021. With all members contributing to a shared wallet, a DAO becomes self-governing and self-regulating, automating the administration of the group. The encoded rules regarding member votes can mechanize certain functions, such as bidding on an artwork. Most DAOs have very active chat rooms where members participate in vigorous debate about any given issue.

“As the career path of Jonas Lund improves and his market value increases, so does the value of a Jonas Lund Token, thus allowing shareholders to profit through dividends and potential sales of the tokens,” states the website of Jonas Lund Token (JLT). JLT is a DAO with 100,000 tokens distributed among parties with voting rights and shared responsibility for the projects that Jonas Lund produces. An advisory board’s vested interest in the artist’s success provides strategy guidance, but all potential projects are presented to token holders, who discuss and vote on what work Lund will produce.

Blockchain is a technology in progress, not a monolithic structure, and artists can exploit its flexibility to remind audiences of its manifold prospects. Blockchain and smart contracts aren’t just impacting the digital sphere, but the breadth of the entire art market. “The idea of smart contracts may be giving artists in the legacy art world confidence to demand the inclusion of resale limitation rights in IRL transactions of physical works,” wrote Yayoi Shionori, arts lawyer and representative for the Chris Burden estate, reflecting on the impact of this emergent technology.

Certainly blockchain offers an opportunity to ensure provenance and reassure owners of the origin and authenticity of the works they purchase. But confidence in one’s artistic value, and the tools to claim it as well? That gift to an artist is beyond measure.

Source: https://www.hugeinc.com/hugemoves/chasing-provenance/

0 notes

Text

On Damien Hirst’s ‘The Currency’ Referendum Part One by Julia Friedman & David Hawkes, November 2021

Damien Hirst, “The Currency,” 2016-2021, 7721. THAT LOW WIND BRINGS YOU SO MUCH STRESS. Detail. Enamel paint, handmade paper, watermark, microdot, hologram, pencil, 7 9/10 × 11 4/5 in (20 × 30 cm). Image: HENI.

Although crypto art is a relatively new phenomenon, the correlation between art and money has been a fashionable topic at least since the late 1930s when Clement Greenberg pointed out the avant-garde’s attachment to the market ‘by an umbilical cord of gold.’ Art and money are both systems of symbolic value, and their convergence seems a foregone conclusion in our age of the image. However, the union of art and money embodied by the NFTs is forced, and far from equal. The NFT does not blend aesthetic value and financial value into a harmonious alliance; it devours the first form of value to feed the second. Taken to its logical conclusion, an art market dominated by NFTs would be a predatory, Darwinian environment in which original works are hunted to physical destruction by their own financialized representations.

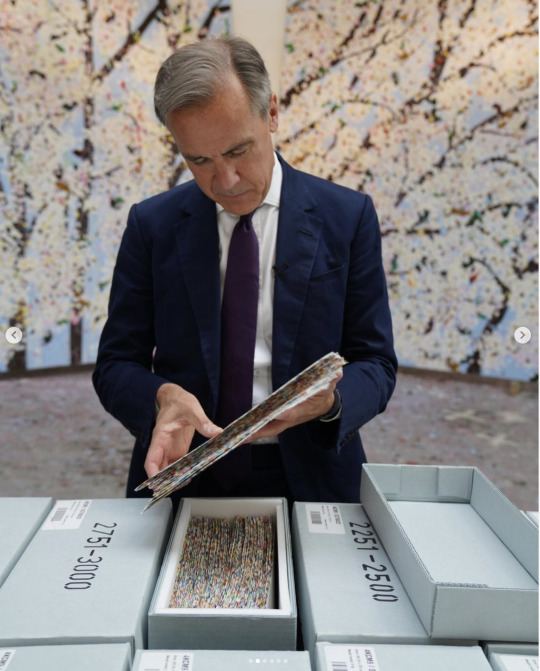

Perhaps that is what piqued the interest of the English artist Damien Hirst, whose work shows a long-standing fascination with predators and predation. Hirst came onto the scene as one of the YBAs in the early 90s, shocking the public with a sculpture of a shark preserved in formaldehyde. His latest and most ambitious project: 'The Currency' is a conceptual, participatory artwork that functions as a controlled experiment about choices, the foremost of which is between the aura of a physical work and the semiotic gravitas of a blockchain representation. This past July, he has offered 10,000 unique NFTs for sale at $2,000 each. Each NFT corresponds to a unique painting on handmade paper, numbered, titled, and signed. The buyers will have until 3pm BST on July 27, 2022 to decide whether they want to keep the NFT or exchange it for the material painting. If they choose the original, the NFT is erased. If they choose the NFT, the painting will be publicly destroyed by the Damien Hirst Studio, following a farewell showing of the doomed works.

Damien Hirst, Instagram, July 22, 2021.

Hirst insists that ‘The Currency’ is a democratic (albeit within an arbitrarily circumscribed demos) and open experiment to test the persistent notion that money and art are interchangeable. This notion has been on the artist’s mind at least since the start of his career. Now he is investigating it, enabled by new technology whose disruptive potential in the art ecosystem recalls Dada’s challenge to the physical conception of art a century earlier. But the new paradigm shift takes place in a new environment, against the background of a fully consumer-oriented society, in which consumerism has been firmly incorporated into art by Andy Warhol, who provided his collectors with their preferred colors in Marilyn Monroe silkscreens, and their preferred flavors of Campbell soup.

With brilliant simplicity ‘The Currency’ condenses a hundred and fifty years of art historical arguments over whether art should be ‘messy’ or ‘clean,’ as well as the relationship between art and money, the roles of ownership and collecting, and many other weighty issues into a single referendum—an art-world version of Brexit. The choice will not be made on aesthetic grounds alone. Considerable monetary motivation is involved, since the NFT is likely to acquire value more rapidly than the original, and so the project will also test whether people value art more than money. Hirst’s experiment should help to determine if a realm of aesthetic experience can be separated from financial value, or whether art and money are at last identical.

Are they? Hirst seems to hint that they are. Each physical painting is carefully protected from counterfeiting, not only by being numbered and titled, but also stamped with a bespoke watermark logo, a microdot, and a hologram, just like paper money. A video of a dialogue between Hirst and Mark Carney, former Governor of the Bank of England, reveals a surprising degree of agreement between the artist and the economist as to the close relation between their respective spheres. Hirst and Carney concur that money is magic, and that financial value is produced by ‘alchemy.’ They both think of money as an autonomous, self-reproducing sign.

Damien Hirst, Instagram, July 16, 2021.

Carney cites Karl Marx as saying that money ‘represents infinite wants,’ which is exactly what one would expect Carney himself to believe: value is produced by desire. But Marx actually said that money represents labor-power. Like Carney, Hirst seems to miss this point, which is strange given that he also quotes the late anthropologist David Graeber. Graeber explored the concept of ‘labor-power’ in depth, showing that it means ‘the human capacity for action,’ or human subjective activity considered in the abstract. The ethical problem with money’s independent power lies in the fact that it is an objectified representation of human life itself.

This ethical critique is absent from Hirst’s project. He lacks a labor theory of value in either economics or aesthetics. He complained to Stephen Fry that prospective buyers often question him about the value of the materials in his diamond-encrusted skull (‘For the Love of God’, 2007), whereas they would never raise the same question regarding the Mona Lisa. Hirst is oblivious to the idea that a work’s value might derive from the quality (or indeed the quantity) of artistic labor involved in its production. And like Carney, he accepts the neoclassical theory that financial value is derived from market forces, and that it represents alienated subjective experiences like ‘confidence’ and ‘trust.’

The theory of value espoused in ‘The Currency’ contrasts sharply with the one expressed in Marcel Duchamp’s ‘assisted readymade’ sculptures. These early works consisted of a manufactured component customized by the artist. The 1914 Bicycle Wheel was a kitchen stool with an overturned bicycle wheel attached to it, thus raising the question of exactly whose labor went into the work. Hirst’s project is an ‘assisted readymade’ in reverse. Its departure point is analogue, but it is actualized via technology: the hand-made paintings have been digitized and analyzed, to provide the potential collectors with high resolution image files and information to place individual works within the series. The irony of ‘The Currency’ is that the physical artwork is threatened by its own NFT—a technology—while its only path to self-preservation also runs through technology. The poison is also the antidote.

While ‘The Currency’ is ostensibly based on free choice, the collectors are limited by the manner of distribution imposed on them by the artist. The work can only be acquired via an application process open for a period of one week. This system was set up to avoid hoarding, and to preserve the authenticity of the referendum by maximizing the number of ‘voters.’ The alternative ‘first come, first served’ model would have favored the most interested buyers, those poised to apply as soon as the subscription was released. This method of ‘allocation’ is closer to an equitable distribution. Each successful applicant is allotted a specific, but randomly chosen work or works. But that is where the randomness ends.

Once revealed to the lucky applicants (demand exceeded supply six-fold), the artworks are allowed to establish their uniqueness. As they receive their high-resolution image, the collectors learn the title of the work. These are AI generated from Hirst’s favorite song lyrics. The title and a set of other unique characteristics including overlaps, drips, texture, density, and weight determine the placement of the work in the series. Each of these categories is ranked by a machine learning algorithm and contextualized within the entire body of work. Similar analysis is made of each piece’s color palette, title, and even the title’s word count (they range between one and eleven words). The collector can see the number and title penciled in on the recto, along with Hirst’s signature, the watermark, the hologram, and the dot. The recto also reveals the degree of bleed, which is not consistent across colors. At this point, the fact the works are not an edition of an image that repeats 10,000 times, but rather a series of unique small-format (20cm x 30cm) paintings becomes impossible to ignore.

Each of the 10,000 works is available for examination online, and collectors are encouraged to ‘compare the rarities in [the] gallery.’ This suggestion to look closely at individual works, and to contextualize them in relation to each other, is a foray into the art historical concept of the ‘series,’ perhaps best known from the work of Monet. Monet’s paintings of his favored motifs—haystacks, Rouen Cathedral, poplar alleys—have a twofold function. They are autonomous, self-contained images, but they are also fragments of the artist’s extended perception of the same motif.

Damien Hirst, “The Currency,” HENI, gallery. Image: HENI.

By urging the viewers to ‘compare rarities in the gallery,’ Hirst revisits the tradition of the ‘series,’ whereby each work is constructed by its context within the whole. He essentially tricks the collectors into very close looking, requiring minute examination of digitized paintings. The technical ability to zoom in to a degree far exceeding he capacity of the naked (or bespectacled) eye takes focus to levels unavailable to connoisseurs of Claude Monet’s work—even those few who were lucky enough to see the entire series at his dealer’s gallery before the individual paintings were sold off and forever separated. And because it is digitized, and 'The Currency' will remain an intact series in perpetuity, regardless of the fate of the individual works.

As Hirst explains in his July 16th interview with Cointelegraph, some initial ambiguity over the uniqueness of individual works was baked into the project from the outset. The aim was to level the playing field for art and money, by removing the “X” factor of the aura. But as soon as the originality of the paintings is established both visually (through zooming in), and statistically (through the information generated by the machine learning algorithm), the objects assert themselves as unique. An alchemical reaction has taken place, and it cannot be reversed.

At this point, the collectors encounter their first true choice: to bond or not to bond with that specific artwork, still only visible to them on the backlit screen, but with the pending promise of an actual, physical encounter. That is, if they ‘swipe right’ and choose the actual painting. What will determine that choice? Sentiment or Luddism will doubtless encourage some collectors to go for the physical paintings. Conversely, those who see no difference between paintings and their encryptions in the blockchain will probably elect to keep their NFTs, and the corresponding paintings will be destroyed. With gleeful perversity, Hirst plans to exhibit the paintings that were not ‘traded’ for their NFTs before they are destroyed, giving the owners a last chance to commune with them, and time for the implications of their destruction to sink in—rather like those seafood restaurants that let customers select their dinner from a tank of live fish.

What makes the project especially intriguing, is that while Hirst’s experiment tackles such hefty moral issues as trust and greed, the vote is not a straightforward ethical choice—it is as much about aesthetics. In the discussions of Western art over the past hundred and fifty years tastes have been divided between those who prefer ‘messy’ art that incorporates chance, painterly gesture and the subconscious, and supporters of ‘clean’ art that is restricted and refined to effect minimalistic visual outcomes. Such movements as Impressionism, Fauvism, Abstract Expressionism, Painterly Abstraction and Art Informel favored the ‘messy’ school, while Geometric Abstraction, Minimalism, Op-Art and Hard-Edge Abstraction tended towards the ‘clean.’

Damien Hirst, “The Currency,” Above: Overlaps. Below: Density. Image: HENI.

One of the benefits of ‘The Currency’ project will be a vote on this issue. Although they may look similar at first glance, upon AI examination aided by high resolution optics each of Hirst’s 10,000 dot paintings falls somewhere along the historical spectrum of messy-to-clean. And it is the personal preference of the collector regarding such factors as the density of the marks, their overlap, the texture of the paint, its bleed through hand-made paper, the presence or absence of drips, that determine whether a given painting can save itself from destruction by producing a taste-based emotional attachment in the collector.

We are now in the second phase of the project—the redemption—when the owners of NFT tenders can exchange them for physical art. Once the painting is collected (in person, or via a shipping courier), its NFT is destroyed. This process cannot be reversed. We will not know how the experiment ends until late July 2022, but by looking at the exchange and sales information three and a half months after the allocation, we can see that the vast range of secondary market prices (anywhere between $3,700 and $175,371) is driven by the unique characteristics of the works as they were digitally conveyed to the collectors. The discrepancy in resale price betrays individual collectors’ preferences for clean or messy, more-or-less marked edges, long or short titles, and even for certain words. Therefore, although this project is made possible by new technology, its fate will be determined by the irreducibly, inimitably human factor of taste making ‘The Currency’ referendum only the latest iteration of an old dispute. WM __________________________

Julia Friedman is a Russian-born art historian, writer and curator. After receiving her Ph.D. in Art History from Brown University in 2005, she has researched and taught in the US, UK and Japan. Her work appeared in Artforum, The New Criterion, Quillette and Atheneum Review. www.juliafriedman.org

David Hawkes is Professor of English Literature at Arizona State University. His work has appeared in The Nation, the Times Literary Supplement, The New Criterion, In These Times and numerous scholarly journals. He is the author of seven books, most recently The Reign of Anti-logos: Performance in Postmodernity (Palgrave Macmillan, 2020).

Source: https://whitehotmagazine.com/articles/-currency-referendum/5209

1 note

·

View note

Text

On Damien Hirst’s ‘The Currency’ Referendum Part Two by By Julia Friedman & David Hawkes, August 2022

The result of ‘The Currency’ vote is in: 5,149 paintings to 4,851 NFTs. The majority of NFT holders opted to exchange their non-fungible tokens for authentic, original, material paintings, and artworld commentators showed restrained elation. Even the Discord discussion board, on which participants in the project reveal the motives behind their choices, is full of testimonials fetishizing the artworks’ materiality. A typical exclamation is: ‘Am so excited I can’t wait to see and smell the paint.’

While it is tempting to read the result as a definitive endorsement of the Benjaminian ‘aura’, it was hardly a ‘resounding preference for traditional art’ as Artnet’s Caroline Goldstein optimistically claims. Until the last few hours before the deadline, the NFTs were in the lead—662 votes against them were cast on the very last day. Was it peer pressure that shifted the balance, causing the eleventh-hour flip in favor of physical paintings? Or was it a visceral recoil against the idea of annihilating unique works of art? The precedents of ‘BurntBanksy,’ and other experiments in which artworks were destroyed in order to increase the value of the correlating NFTs, resulted in public condemnation of this blatant preference for money over aesthetics. Those who purchased ‘The Currency’ were not immune to veneration of the aura; their collective decision was not made on financial grounds alone. This follows from the fact that while NFTs in general lost a great deal of value by June of 2022, this did not produce a wave of selling among the holders of ‘The Currency.’ Hirst’s NFTs sustained a stable marketplace unaffected by fluctuations in the value of other non-fungible tokens. The true value of these works must therefore reside elsewhere, beyond the reach of digital trends.

Much like the Brexit referendum to which Hirst’s project alludes, his poll seems to raise more questions than it answers. The intriguing provocation of ‘The Currency’ lies in its suggestion that art and money could be one. The pricing of the paintings becomes part of the artwork: NFTs originally sold for $2,000 each are now placed for resale on Heni for anywhere between $8,000 and $200,000, with one offered up for an irrational $30,000,000. This disparity echoes Yves Klein’s 1957 “Monochrome Propositions. Blue Period” exhibition in Milan, where Klein presented eleven ostensibly identical paintings for sale at different prices that were supposed to correspond to the subjective significance they held for the individual buyer. The holders of Hirst’s ‘currency’ similarly translate the monetary value of the NFTs into the experience of participating in the project. As one buyer commented on the Discord message-board:

"I have never been about stuff or financial returns on this…. To me this is about being part of a huge project that has been created by one of the biggest living artists. That alone is enough for me. The exhibition and all the other stuff, that in itself is absolutely huge to me. I will never forget these experiences."

Ostensibly, the question posited by ‘The Currency’ is whether the artworld is driven by financial or aesthetic considerations. However, participants and observers alike seem to be undermining the principle of that question by finding aesthetic pleasure in financial transactions. In postmodernity, everything can be translated into financial terms—personal relationships quite as much as aesthetic experiences. Advocates of NFTs often refer to themselves as a ‘community,’ not just out of sentiment, but from a hard-headed calculation that a sense of community also has financial value. The purchasers of ‘The Currency’ create its social value as well as its commercial worth. This is among the project’s main selling-points. As Hirst puts it: ‘The whole project is an artwork, and anyone who buys ‘The Currency’ will participate in this work.’

Screenshot of the Marketplace on Heni with NFTs at highest prices.

Therefore, although a slim majority of Hirst’s buyers chose to retain their paintings and destroy their NFTs, this cannot be taken to indicate that they value art over money. Perhaps they prefer physical art to the disembodied kind. But physical art has long ceased to refer to the real world. The rise of modernism produced a dramatic efflorescence of ever-more abstract art, ultimately arriving at pure conceptualism. At the same time, financial value departed the physical body of bullion, and even banknotes, finally manifesting itself in the entirely imaginary form of ‘derivatives.’ Art and money have both been moving towards abstraction since the late nineteenth century. Hirst’s project suggests that abstraction facilitates the union of art and money which become indistinguishable to the degree that they become immaterial. Another word for ‘immaterial’ is ‘spiritual,’ and the discussion on the Discord board often takes a quasi-theological tone:

"I think traditional art is weighed more about the art and slightly less about money. NFTs seem (in the majority) to flip that. I think that's what makes me uncomfortable and opens the door to a lot of demons for people."

The ethical problem exposed by Hirst’s project is not that people prefer money to art. It is that art and money become the same thing if treated interchangeably. The second phase of ‘The Currency’—the ‘redemption,’ in which the owners of NFTs could exchange their inscription on the blockchain for physical Tenders—was presented as performative, even ritualistic, and it drove this point home.

Here is how the process transpired. Having accessed the MetaMask digital wallet, where the allocated NFTs were stored, the owners were asked to ‘select […] NFTs you would like to exchange for the physical artwork.’ After choosing the work, and paying shipping costs, the owner was informed, in bold font: ‘In order the finalize the exchange process, you need to burn your NFT(s). If you do not do this, your artwork(s) will not be sent.’ Underneath was a window to check, along with an accompanying statement of consent: ‘I understand that burning my NFT(s) permanently destroys my NFT(s) and cannot be undone.’ Below that a button inscribed ‘Burn Using MetaMask’ promised to initiate the process with a single click. The following screen ‘BURNING NFT(S)’ confirmed that the process was under way.

Hirst clearly aimed to emphasize the irreversibility of the choice to burn digital tokens. Yet burning an NFT is never truly, literally destructive. It is just a commonly used turn of phrase. The project’s originality was the initial Sophie’s Choice, which stipulated that selecting one iteration of the image would automatically condemn the other to annihilation. While the owner is asked to ‘burn’ whichever iteration is rejected, the action is metaphorical in the case of NFTs, but undeniably, irrevocably physical in the case of the paintings. There is no fire and smoke when NFTs are burned: they are ‘re-homed,’ sent to a null address and thus made unusable. In dramatic contrast, the paintings condemned for destruction will first be placed on view at London’s Newport Street Gallery in early September, and then burned, as part of an exhibition, at a specified time of each day. The exhibition will culminate in a massive conflagration, in which the remaining artworks will meet a fiery end, as their creator looks on.

In a perfect poetic happenstance, the very last NFT (#8272) exchanged for a painting just before the deadline of 3:00 GMT on July 27, 2022, was titled “They fought for what they had.” It is as if the 10,000 physical paintings produced in 2016, four years before the NFT project was launched, struggled for their own survival like living creatures. Rather sadistically, Hirst made sure that ‘saving’ the physical paintings required taking action, since doing nothing would result in a default retention of the NFT(s). Doing nothing also constituted effective consent to the destruction of the NFT’s tangible equivalent, the painting. And this destruction is no discrete deletion at an uncertain time and place, but a spectacular extinction by public burning. Moreover, these executions are cruelly extended over a lengthy period, and the witnessing public will be implicated in the act.

The parallels with the public executions of yore are surely deliberate, and deliberately uncomfortable. Half a millennium ago, Savonarola’s Florence blazed with ‘bonfires of the vanities’ in which sinful art, books and commodities were burnt in public squares. By all accounts they were impressive events: iconoclasm has its own aesthetic. And in the 1930s the Nazis after exhibiting ‘degenerate art’ in Munich, incinerated it in the courtyard of the ‘Old Fire Station’ in Berlin. Ironically, while it was supposed to show the evils of modernism, the infamous Munich exhibition turned out to be the first 20th century blockbuster, with over two million attendees. ‘The Currency’ provocatively alludes to such precedents, unavoidably connecting the participants to the culling of 4,851 original artworks. This is not a decision to be made lightly.

Last second of the exchange period, screenshot.

Hirst’s own choice was to retain the 1,000 NFTs that belong to him personally. In an Instagram post following the announcement of the results, he presented his decision as both flippant and agonizing:

"I have been all over the fucking shop with my decision making…. I believe in art and art in all its forms but in the end I thought fuck it! this zone is so fucking exiting and the one I know least about and I love this NFT community it blows my mind…. I’m amazed at how this community breeds support and seems to care about shit so in the end I decided I have to keep all my 1000 currency as NFTs otherwise it wouldn’t carry on being a proper adventure for me and so I decided I need to show my 100 percent support and confidence in the NFT world (even though it means I will have to destroy the corresponding 1000 physical artworks). Eeeeeeeek! I still don’t know what I’m doing and I have no idea what the future holds, whether the NFTs or physicals are going to be more valuable or less. But that is art! The fun, part of the journey and maybe the point of the whole project. Even after one year, I feel the journey is just beginning. I have already learnt so much and it’s only been a year and I am so proud to have created something alive, something mad and provocative and been a passenger (along with all the other participants in the currency) and to help build a fantastic community on @heni. Long may it last and I can’t wait for the next twists and turns."

Hirst’s exuberant, rambling monologue describes his vacillation between paintings and NFTs, before exploding in the punk ‘fuck it!’ The artist’s choice is not coldly financial; as he explains, it reflects his support of the NFT community. Moreover, the very number of 10,000 NFTs/paintings that comprise this project is presumably a reference to the pioneering NFT known as ‘CryptoPunks,’ which consists of 10,000 unique collectable characters. Now CryptoPunks price had plunged, and the conversation around them fading, while ‘The Currency’ is not only healthy in terms of valuation, but continues to generate considerable interest. Perhaps Hirst’s vote for the NFTs is also a gracious gesture of a victor displaying his good sportsmanship.

youtube

When digital NFTs first appeared in the artworld, it was frequently suggested that they threatened the existence of the objects they represented. ‘The Currency’ tested this hypothesis, creating a controlled experiment in which people had to make an irreversible choice between NFTs and physical art. As the experiment unfolded, however, the threat of annihilation hovering over the physical artworks seems to have reasserted the value of the ‘aura’—the unique, irreplicable significance possessed by original artworks. By bluntly stressing the process of extermination, Hirst once again directs our attention to the physical possibility of death. While he seems somewhat dismayed at the prospect of destroying his own work, Hirst understands that the destruction of art is itself a form of art. He claims to have created ‘something alive, something mad and provocative’ and excitedly anticipates future adventures: ‘I can’t wait for the next twists and turns.’ Like his canonical formaldehyde shark entitled ‘The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living,’ Hirst’s NFT project uses death to locate life. ‘The Currency’ is a memento mori, intended to help us appreciate life. Or is it? A more cynical reading of this project might concur with Leo Tolstoy that an awareness of death actually undermines the meaning of life. Either way, Hirst’s experiment will not end with the planned incinerations. The union of art and money contains possibilities, and dangers, that will continue to inform aesthetics and economics as long as those categories have meaning. WM

__________________________

Julia Friedman is a Russian-born art historian, writer and curator. After receiving her Ph.D. in Art History from Brown University in 2005, she has researched and taught in the US, UK and Japan. Her work appeared in Artforum, The New Criterion, Quillette and Atheneum Review. www.juliafriedman.org

David Hawkes is Professor of English Literature at Arizona State University. His work has appeared in The Nation, the Times Literary Supplement, The New Criterion, In These Times and numerous scholarly journals. He is the author of seven books, most recently The Reign of Anti-logos: Performance in Postmodernity (Palgrave Macmillan, 2020).

Source: https://whitehotmagazine.com/articles/s-currency-referendum-part-two/5495

0 notes

Text

From An Interview with David Hammons

1. I CAN'T STAND ART ACTUALLY. I'VE NEVER, EVER LIKED ART, EVER. I NEVER TOOK IT IN SCHOOL. 2. WHEN I WAS IN CALIFORNIA, ARTISTS WOULD WORK FOR YEARS AND NEVER HAVE A SHOW. SO SHOWING HAS NEVER BEEN THAT IMPORTANT TO ME. WE USED TO CUSS PEOPLE OUT: PEOPLE WHO BOUGHT OUR WORK, DEALERS, ETC., BECAUSE THAT PART OF BEING AN ARTIST WAS ALWAYS A JOKE TO US. WHEN I CAME TO NEW YORK, I DIDN'T SEE ANY OF THAT. EVERYBODY WAS JUST GROVELING AND TOMMING, ANYTHING TO BE IN THE ROOM WITH SOMEBODY WITH SOME MONEY. THERE WERE NO BAD GUYS HERE; SO I SAID, "LET ME BE A BAD GUY," OR ATTEMPT TO BE A BAD GUY, OR PLAY WITH THE BAD AREAS AND SEE WHAT HAPPENS. 3. I WAS TRYING TO FIGURE OUT WHY BLACK PEOPLE WERE CALLED SPADES, AS OPPOSED TO CLUBS. BECAUSE I REMEMBER BEING CALLED A SPADE ONCE, AND I DIDN'T KNOW WHAT IT MEANT; NIGGER I KNEW BUT SPADE I STILL DON'T. SO I TOOK THE SHAPE, AND STARTED PAINTING IT. 4. I JUST LOVE THE HOUSES IN THE SOUTH, THE WAY THEY BUILT THEM. THAT NEGRITUDE ARCHITECTURE. I REALLY LOVE TO WATCH THE WAY BLACK PEOPLE MAKE THINGS, HOUSES OR MAGAZINE STANDS IN HARLEM, FOR INSTANCE. JUST THE WAY WE USE CARPENTRY. NOTHING FITS, BUT EVERYTHING WORKS. THE DOOR CLOSES, IT KEEPS THINGS FROM COMING THROUGH. BUT IT DOESN'T HAVE THAT NEATNESS ABOUT IT, THE WAY WHITE PEOPLE PUT THINGS TOGETHER; EVERYTHING IS A THIRTY-SECOND OF AN INCH OFF. 5. THAT'S WHY I LIKE DOING STUFF BETTER ON THE STREET, BECAUSE THE ART BECOMES JUST ONE OF THE OBJECTS THAT'S IN THE PATH OF YOUR EVERYDAY EXISTENCE. IT'S WHAT YOU MOVE THROUGH, AND IT DOESN'T HAVE ANY SENIORITY OVER ANYTHING ELSE. THOSE PIECES WERE ALL ABOUT MAKING SURE THAT THE BLACK VIEWER HAD A REFLECTION OF HIMSELF IN THE WORK. WHITE VIEWERS HAVE TO LOOK AT SOMEONE ELSE'S CULTURE IN THOSE PIECES AND SEE VERY LITTLE OF THEMSELVES IN IT. 6. ANYONE WHO DECIDES TO BE AN ARTIST SHOULD REALIZE THAT IT'S A POVERTY TRIP. TO GO INTO THIS PROFESSION IS LIKE GOING INTO THE MONASTERY OR SOMETHING; IT'S A VOW OF POVERTY I ALWAYS THOUGHT. TO BE AN ARTIST AND NOT EVEN TO DEAL WITH THAT POVERTY THING, THAT'S A WASTE OF TIME; OR TO BE AROUND PEOPLE COMPLAINING ABOUT THAT. MY KEY IS TO TAKE AS MUCH MONEY HOME AS POSSIBLE. ABANDON ANY ART FORM THAT COSTS TOO MUCH. INSIST THAT IT'S AS CHEAP AS POSSIBLE IS NUMBER ONE AND ALSO THAT IT'S AESTHETICALLY CORRECT. AFTER THAT ANYTHING GOES. AND THAT KEEPS EVERYTHING INTERESTING FOR ME. 7. I DON'T KNOW WHAT MY WORK IS. I HAVE TO WAIT TO HEAR THAT FROM SOMEONE. I WOULD LIKE TO BURN THE PIECE. I THINK THAT WOULD BE NICE VISUALLY. VIDEOTAPE THE BURNING OF IT. AND SHOOT SOME SLIDES. THE SLIDES WOULD THEN BE A PIECE IN ITSELF. I'M GETTING INTO THAT NOW: THE SLIDES ARE THE ART PIECES AND THE ART PIECES DON'T EXIST. 8. IF YOU KNOW WHO YOU ARE THEN IT'S EASY TO MAKE ART. MOST PEOPLE ARE REALLY CONCERNED ABOUT THEIR IMAGE. ARTISTS HAVE ALLOWED THEMSELVES TO BE BOXED IN BY SAYING "YES" ALL THE TIME BECAUSE THEY WANT TO BE SEEN, AND THEY SHOULD BE SAYING "NO." I DO MY STREET ART MAINLY TO KEEP ROOTED IN THAT "WHO I AM." BECAUSE THE ONLY THING THAT'S REALLY GOING ON IS IN THE STREET; THAT'S WHERE SOMETHING IS REALLY HAPPENING. IT ISN'T HAPPENING IN THESE GALLERIES. 9. DOING THINGS IN THE STREET IS MORE POWERFUL THAN ART I THINK. BECAUSE ART HAS GOTTEN SO....I DON'T KNOW WHAT THE FUCK ART IS ABOUT NOW. IT DOESN'T DO ANYTHING. LIKE MALCOLM X SAID, IT'S LIKE NOVOCAINE. IT USED TO WAKE YOU UP BUT NOW IT PUTS YOU TO SLEEP. I THINK THAT ART NOW IS PUTTING PEOPLE TO SLEEP. THERE'S SO MUCH OF IT AROUND IN THIS TOWN THAT IT DOESN'T MEAN ANYTHING. THAT'S WHY THE ARTIST HAS TO BE VERY CAREFUL WHAT HE SHOWS AND WHEN HE SHOWS NOW. BECAUSE THE PEOPLE AREN'T REALLY LOOKING AT ART, THEY'RE LOOKING AT EACH OTHER AND EACH OTHER'S CLOTHES AND EACH OTHER'S HAIRCUTS. 10. THE ART AUDIENCE IS THE WORST AUDIENCE IN THE WORLD. IT'S OVERLY EDUCATED, IT'S CONSERVATIVE, IT'S OUT TO CRITICIZE NOT TO UNDERSTAND, AND IT NEVER HAS ANY FUN. WHY SHOULD I SPEND MY TIME PLAYING TO THAT AUDIENCE? DAVID HAMMONS 1986

Source: https://stuartmiddleton.blogspot.com/2014/12/from-interview-with-david-hammons-1.html

0 notes

Text

The AI that creates any picture you want

youtube

Beginning in January 2021, advances in AI research have produced a plethora of deep-learning models capable of generating original images from simple text prompts, effectively extending the human imagination. Researchers at OpenAI, Google, Facebook, and others have developed text-to-image tools that they have not yet released to the public, and similar models have proliferated online in the open-source arena and at smaller companies like Midjourney.

These tools represent a massive cultural shift because they remove the requirement for technical labor from the process of image-making. Instead, they select for creative ideation, skillful use of language, and curatorial taste. The ultimate consequences are difficult to predict, but — like the invention of the camera, and the digital camera thereafter — these algorithms herald a new, democratized form of expression that will commence another explosion in the volume of imagery produced by humans. But, like other automated systems trained on historical data and internet images, they also come with risks that have not been resolved.

The video above is a primer on how we got here, how this technology works, and some of the implications. And for an extended discussion about what this means for human artists, designers, and illustrators, check out this bonus video: https://youtu.be/sFBfrZ-N3G4

Midjourney: https://www.midjourney.com/

List of free AI Art tools: https://pharmapsychotic.com/tools.html

Sources:

https://medium.com/artists-and-machine-intelligence/a-journey-through-multiple-dimensions-and-transformations-in-space-the-final-frontier-d8435d81ca51

https://jxmo.notion.site/The-Weird-and-Wonderful-World-of-AI-Art-b9615a2e7278435b98380ff81ae1cf09

https://va2rosa.medium.com/copyright-storm-authorship-in-the-age-of-ai-baba554aa617

https://arnicas.substack.com/p/titaa-28-visual-poetry-humans-and?s=r

https://tedunderwood.com/2021/10/21/latent-spaces-of-culture/

https://ml.berkeley.edu/blog/posts/clip-art/

https://arxiv.org/abs/1511.02793

https://multimodal.art/

https://openai.com/blog/dall-e/

https://openai.com/blog/clip/

https://openai.com/dall-e-2/

https://laion.ai/laion-5b-a-new-era-of-open-large-scale-multi-modal-datasets/

https://arxiv.org/abs/2110.01963

Source: https://youtu.be/SVcsDDABEkM

0 notes

Text

WHY THE PAST 10 YEARS OF AMERICAN LIFE HAVE BEEN UNIQUELY STUPID. It’s not just a phase. By Jonathan Haidt Illustrations by Nicolás Ortega

Illustration by Nicolás Ortega. Source: "Turris Babel," Coenraet Decker, 1679.

What would it have been like to live in Babel in the days after its destruction? In the Book of Genesis, we are told that the descendants of Noah built a great city in the land of Shinar. They built a tower “with its top in the heavens” to “make a name” for themselves. God was offended by the hubris of humanity and said:

Look, they are one people, and they have all one language; and this is only the beginning of what they will do; nothing that they propose to do will now be impossible for them. Come, let us go down, and confuse their language there, so that they will not understand one another’s speech.

The text does not say that God destroyed the tower, but in many popular renderings of the story he does, so let’s hold that dramatic image in our minds: people wandering amid the ruins, unable to communicate, condemned to mutual incomprehension.

The story of Babel is the best metaphor I have found for what happened to America in the 2010s, and for the fractured country we now inhabit. Something went terribly wrong, very suddenly. We are disoriented, unable to speak the same language or recognize the same truth. We are cut off from one another and from the past.

It’s been clear for quite a while now that red America and blue America are becoming like two different countries claiming the same territory, with two different versions of the Constitution, economics, and American history. But Babel is not a story about tribalism; it’s a story about the fragmentation of everything. It’s about the shattering of all that had seemed solid, the scattering of people who had been a community. It’s a metaphor for what is happening not only between red and blue, but within the left and within the right, as well as within universities, companies, professional associations, museums, and even families.

Babel is a metaphor for what some forms of social media have done to nearly all of the groups and institutions most important to the country’s future—and to us as a people. How did this happen? And what does it portend for American life?

The Rise of the Modern Tower

there is a direction to history and it is toward cooperation at larger scales. We see this trend in biological evolution, in the series of “major transitions” through which multicellular organisms first appeared and then developed new symbiotic relationships. We see it in cultural evolution too, as Robert Wright explained in his 1999 book, Nonzero: The Logic of Human Destiny. Wright showed that history involves a series of transitions, driven by rising population density plus new technologies (writing, roads, the printing press) that created new possibilities for mutually beneficial trade and learning. Zero-sum conflicts—such as the wars of religion that arose as the printing press spread heretical ideas across Europe—were better thought of as temporary setbacks, and sometimes even integral to progress. (Those wars of religion, he argued, made possible the transition to modern nation-states with better-informed citizens.) President Bill Clinton praised Nonzero’s optimistic portrayal of a more cooperative future thanks to continued technological advance.

The early internet of the 1990s, with its chat rooms, message boards, and email, exemplified the Nonzero thesis, as did the first wave of social-media platforms, which launched around 2003. Myspace, Friendster, and Facebook made it easy to connect with friends and strangers to talk about common interests, for free, and at a scale never before imaginable. By 2008, Facebook had emerged as the dominant platform, with more than 100 million monthly users, on its way to roughly 3 billion today. In the first decade of the new century, social media was widely believed to be a boon to democracy. What dictator could impose his will on an interconnected citizenry? What regime could build a wall to keep out the internet?

The high point of techno-democratic optimism was arguably 2011, a year that began with the Arab Spring and ended with the global Occupy movement. That is also when Google Translate became available on virtually all smartphones, so you could say that 2011 was the year that humanity rebuilt the Tower of Babel. We were closer than we had ever been to being “one people,” and we had effectively overcome the curse of division by language. For techno-democratic optimists, it seemed to be only the beginning of what humanity could do.

In February 2012, as he prepared to take Facebook public, Mark Zuckerberg reflected on those extraordinary times and set forth his plans. “Today, our society has reached another tipping point,” he wrote in a letter to investors. Facebook hoped “to rewire the way people spread and consume information.” By giving them “the power to share,” it would help them to “once again transform many of our core institutions and industries.”

In the 10 years since then, Zuckerberg did exactly what he said he would do. He did rewire the way we spread and consume information; he did transform our institutions, and he pushed us past the tipping point. It has not worked out as he expected.

Things Fall Apart

historically, civilizations have relied on shared blood, gods, and enemies to counteract the tendency to split apart as they grow. But what is it that holds together large and diverse secular democracies such as the United States and India, or, for that matter, modern Britain and France?

Social scientists have identified at least three major forces that collectively bind together successful democracies: social capital (extensive social networks with high levels of trust), strong institutions, and shared stories. Social media has weakened all three. To see how, we must understand how social media changed over time—and especially in the several years following 2009.

In their early incarnations, platforms such as Myspace and Facebook were relatively harmless. They allowed users to create pages on which to post photos, family updates, and links to the mostly static pages of their friends and favorite bands. In this way, early social media can be seen as just another step in the long progression of technological improvements—from the Postal Service through the telephone to email and texting—that helped people achieve the eternal goal of maintaining their social ties.

But gradually, social-media users became more comfortable sharing intimate details of their lives with strangers and corporations. As I wrote in a 2019 Atlantic article with Tobias Rose-Stockwell, they became more adept at putting on performances and managing their personal brand—activities that might impress others but that do not deepen friendships in the way that a private phone conversation will.

Once social-media platforms had trained users to spend more time performing and less time connecting, the stage was set for the major transformation, which began in 2009: the intensification of viral dynamics.

Before 2009, Facebook had given users a simple timeline––a never-ending stream of content generated by their friends and connections, with the newest posts at the top and the oldest ones at the bottom. This was often overwhelming in its volume, but it was an accurate reflection of what others were posting. That began to change in 2009, when Facebook offered users a way to publicly “like” posts with the click of a button. That same year, Twitter introduced something even more powerful: the “Retweet” button, which allowed users to publicly endorse a post while also sharing it with all of their followers. Facebook soon copied that innovation with its own “Share” button, which became available to smartphone users in 2012. “Like” and “Share” buttons quickly became standard features of most other platforms.

Shortly after its “Like” button began to produce data about what best “engaged” its users, Facebook developed algorithms to bring each user the content most likely to generate a “like” or some other interaction, eventually including the “share” as well. Later research showed that posts that trigger emotions––especially anger at out-groups––are the most likely to be shared.

Illustration by Nicolás Ortega. Source: Belshazzar’s Feast, John Martin, 1820.

By 2013, social media had become a new game, with dynamics unlike those in 2008. If you were skillful or lucky, you might create a post that would “go viral” and make you “internet famous” for a few days. If you blundered, you could find yourself buried in hateful comments. Your posts rode to fame or ignominy based on the clicks of thousands of strangers, and you in turn contributed thousands of clicks to the game.

This new game encouraged dishonesty and mob dynamics: Users were guided not just by their true preferences but by their past experiences of reward and punishment, and their prediction of how others would react to each new action. One of the engineers at Twitter who had worked on the “Retweet” button later revealed that he regretted his contribution because it had made Twitter a nastier place. As he watched Twitter mobs forming through the use of the new tool, he thought to himself, “We might have just handed a 4-year-old a loaded weapon.”

As a social psychologist who studies emotion, morality, and politics, I saw this happening too. The newly tweaked platforms were almost perfectly designed to bring out our most moralistic and least reflective selves. The volume of outrage was shocking.

It was just this kind of twitchy and explosive spread of anger that James Madison had tried to protect us from as he was drafting the U.S. Constitution. The Framers of the Constitution were excellent social psychologists. They knew that democracy had an Achilles’ heel because it depended on the collective judgment of the people, and democratic communities are subject to “the turbulency and weakness of unruly passions.” The key to designing a sustainable republic, therefore, was to build in mechanisms to slow things down, cool passions, require compromise, and give leaders some insulation from the mania of the moment while still holding them accountable to the people periodically, on Election Day.

The tech companies that enhanced virality from 2009 to 2012 brought us deep into Madison’s nightmare. Many authors quote his comments in “Federalist No. 10” on the innate human proclivity toward “faction,” by which he meant our tendency to divide ourselves into teams or parties that are so inflamed with “mutual animosity” that they are “much more disposed to vex and oppress each other than to cooperate for their common good.”

But that essay continues on to a less quoted yet equally important insight, about democracy’s vulnerability to triviality. Madison notes that people are so prone to factionalism that “where no substantial occasion presents itself, the most frivolous and fanciful distinctions have been sufficient to kindle their unfriendly passions and excite their most violent conflicts.”

Social media has both magnified and weaponized the frivolous. Is our democracy any healthier now that we’ve had Twitter brawls over Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s tax the rich dress at the annual Met Gala, and Melania Trump’s dress at a 9/11 memorial event, which had stitching that kind of looked like a skyscraper? How about Senator Ted Cruz’s tweet criticizing Big Bird for tweeting about getting his COVID vaccine?

It’s not just the waste of time and scarce attention that matters; it’s the continual chipping-away of trust. An autocracy can deploy propaganda or use fear to motivate the behaviors it desires, but a democracy depends on widely internalized acceptance of the legitimacy of rules, norms, and institutions. Blind and irrevocable trust in any particular individual or organization is never warranted. But when citizens lose trust in elected leaders, health authorities, the courts, the police, universities, and the integrity of elections, then every decision becomes contested; every election becomes a life-and-death struggle to save the country from the other side. The most recent Edelman Trust Barometer (an international measure of citizens’ trust in government, business, media, and nongovernmental organizations) showed stable and competent autocracies (China and the United Arab Emirates) at the top of the list, while contentious democracies such as the United States, the United Kingdom, Spain, and South Korea scored near the bottom (albeit above Russia).

Recent academic studies suggest that social media is indeed corrosive to trust in governments, news media, and people and institutions in general. A working paper that offers the most comprehensive review of the research, led by the social scientists Philipp Lorenz-Spreen and Lisa Oswald, concludes that “the large majority of reported associations between digital media use and trust appear to be detrimental for democracy.” The literature is complex—some studies show benefits, particularly in less developed democracies—but the review found that, on balance, social media amplifies political polarization; foments populism, especially right-wing populism; and is associated with the spread of misinformation.

When people lose trust in institutions, they lose trust in the stories told by those institutions. That’s particularly true of the institutions entrusted with the education of children. History curricula have often caused political controversy, but Facebook and Twitter make it possible for parents to become outraged every day over a new snippet from their children’s history lessons––and math lessons and literature selections, and any new pedagogical shifts anywhere in the country. The motives of teachers and administrators come into question, and overreaching laws or curricular reforms sometimes follow, dumbing down education and reducing trust in it further. One result is that young people educated in the post-Babel era are less likely to arrive at a coherent story of who we are as a people, and less likely to share any such story with those who attended different schools or who were educated in a different decade.

The former CIA analyst Martin Gurri predicted these fracturing effects in his 2014 book, The Revolt of the Public. Gurri’s analysis focused on the authority-subverting effects of information’s exponential growth, beginning with the internet in the 1990s. Writing nearly a decade ago, Gurri could already see the power of social media as a universal solvent, breaking down bonds and weakening institutions everywhere it reached. He noted that distributed networks “can protest and overthrow, but never govern.” He described the nihilism of the many protest movements of 2011 that organized mostly online and that, like Occupy Wall Street, demanded the destruction of existing institutions without offering an alternative vision of the future or an organization that could bring it about.

Gurri is no fan of elites or of centralized authority, but he notes a constructive feature of the pre-digital era: a single “mass audience,” all consuming the same content, as if they were all looking into the same gigantic mirror at the reflection of their own society. In a comment to Vox that recalls the first post-Babel diaspora, he said:

The digital revolution has shattered that mirror, and now the public inhabits those broken pieces of glass. So the public isn’t one thing; it’s highly fragmented, and it’s basically mutually hostile. It’s mostly people yelling at each other and living in bubbles of one sort or another.

Mark Zuckerberg may not have wished for any of that. But by rewiring everything in a headlong rush for growth—with a naive conception of human psychology, little understanding of the intricacy of institutions, and no concern for external costs imposed on society—Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and a few other large platforms unwittingly dissolved the mortar of trust, belief in institutions, and shared stories that had held a large and diverse secular democracy together.

I think we can date the fall of the tower to the years between 2011 (Gurri’s focal year of “nihilistic” protests) and 2015, a year marked by the “great awokening” on the left and the ascendancy of Donald Trump on the right. Trump did not destroy the tower; he merely exploited its fall. He was the first politician to master the new dynamics of the post-Babel era, in which outrage is the key to virality, stage performance crushes competence, Twitter can overpower all the newspapers in the country, and stories cannot be shared (or at least trusted) across more than a few adjacent fragments—so truth cannot achieve widespread adherence.

The many analysts, including me, who had argued that Trump could not win the general election were relying on pre-Babel intuitions, which said that scandals such as the Access Hollywood tape (in which Trump boasted about committing sexual assault) are fatal to a presidential campaign. But after Babel, nothing really means anything anymore––at least not in a way that is durable and on which people widely agree.

Politics After Babel

“politics is the art of the possible,” the German statesman Otto von Bismarck said in 1867. In a post-Babel democracy, not much may be possible.

Of course, the American culture war and the decline of cross-party cooperation predates social media’s arrival. The mid-20th century was a time of unusually low polarization in Congress, which began reverting back to historical levels in the 1970s and ’80s. The ideological distance between the two parties began increasing faster in the 1990s. Fox News and the 1994 “Republican Revolution” converted the GOP into a more combative party. For example, House Speaker Newt Gingrich discouraged new Republican members of Congress from moving their families to Washington, D.C., where they were likely to form social ties with Democrats and their families.

So cross-party relationships were already strained before 2009. But the enhanced virality of social media thereafter made it more hazardous to be seen fraternizing with the enemy or even failing to attack the enemy with sufficient vigor. On the right, the term RINO (Republican in Name Only) was superseded in 2015 by the more contemptuous term cuckservative, popularized on Twitter by Trump supporters. On the left, social media launched callout culture in the years after 2012, with transformative effects on university life and later on politics and culture throughout the English-speaking world.

What changed in the 2010s? Let’s revisit that Twitter engineer’s metaphor of handing a loaded gun to a 4-year-old. A mean tweet doesn’t kill anyone; it is an attempt to shame or punish someone publicly while broadcasting one’s own virtue, brilliance, or tribal loyalties. It’s more a dart than a bullet, causing pain but no fatalities. Even so, from 2009 to 2012, Facebook and Twitter passed out roughly 1 billion dart guns globally. We’ve been shooting one another ever since.

Social media has given voice to some people who had little previously, and it has made it easier to hold powerful people accountable for their misdeeds, not just in politics but in business, the arts, academia, and elsewhere. Sexual harassers could have been called out in anonymous blog posts before Twitter, but it’s hard to imagine that the #MeToo movement would have been nearly so successful without the viral enhancement that the major platforms offered. However, the warped “accountability” of social media has also brought injustice—and political dysfunction—in three ways.

First, the dart guns of social media give more power to trolls and provocateurs while silencing good citizens. Research by the political scientists Alexander Bor and Michael Bang Petersen found that a small subset of people on social-media platforms are highly concerned with gaining status and are willing to use aggression to do so. They admit that in their online discussions they often curse, make fun of their opponents, and get blocked by other users or reported for inappropriate comments. Across eight studies, Bor and Petersen found that being online did not make most people more aggressive or hostile; rather, it allowed a small number of aggressive people to attack a much larger set of victims. Even a small number of jerks were able to dominate discussion forums, Bor and Petersen found, because nonjerks are easily turned off from online discussions of politics. Additional research finds that women and Black people are harassed disproportionately, so the digital public square is less welcoming to their voices.

Illustration by Nicolás Ortega. Source: Venus and Cupid, Pierre-Maximilien Delafontaine, by 1860.

Second, the dart guns of social media give more power and voice to the political extremes while reducing the power and voice of the moderate majority. The “Hidden Tribes” study, by the pro-democracy group More in Common, surveyed 8,000 Americans in 2017 and 2018 and identified seven groups that shared beliefs and behaviors. The one furthest to the right, known as the “devoted conservatives,” comprised 6 percent of the U.S. population. The group furthest to the left, the “progressive activists,” comprised 8 percent of the population. The progressive activists were by far the most prolific group on social media: 70 percent had shared political content over the previous year. The devoted conservatives followed, at 56 percent.

These two extreme groups are similar in surprising ways. They are the whitest and richest of the seven groups, which suggests that America is being torn apart by a battle between two subsets of the elite who are not representative of the broader society. What’s more, they are the two groups that show the greatest homogeneity in their moral and political attitudes. This uniformity of opinion, the study’s authors speculate, is likely a result of thought-policing on social media: “Those who express sympathy for the views of opposing groups may experience backlash from their own cohort.” In other words, political extremists don’t just shoot darts at their enemies; they spend a lot of their ammunition targeting dissenters or nuanced thinkers on their own team. In this way, social media makes a political system based on compromise grind to a halt.

Finally, by giving everyone a dart gun, social media deputizes everyone to administer justice with no due process. Platforms like Twitter devolve into the Wild West, with no accountability for vigilantes. A successful attack attracts a barrage of likes and follow-on strikes. Enhanced-virality platforms thereby facilitate massive collective punishment for small or imagined offenses, with real-world consequences, including innocent people losing their jobs and being shamed into suicide. When our public square is governed by mob dynamics unrestrained by due process, we don’t get justice and inclusion; we get a society that ignores context, proportionality, mercy, and truth.

Structural Stupidity

since the tower fell, debates of all kinds have grown more and more confused. The most pervasive obstacle to good thinking is confirmation bias, which refers to the human tendency to search only for evidence that confirms our preferred beliefs. Even before the advent of social media, search engines were supercharging confirmation bias, making it far easier for people to find evidence for absurd beliefs and conspiracy theories, such as that the Earth is flat and that the U.S. government staged the 9/11 attacks. But social media made things much worse.

The most reliable cure for confirmation bias is interaction with people who don’t share your beliefs. They confront you with counterevidence and counterargument. John Stuart Mill said, “He who knows only his own side of the case, knows little of that,” and he urged us to seek out conflicting views “from persons who actually believe them.” People who think differently and are willing to speak up if they disagree with you make you smarter, almost as if they are extensions of your own brain. People who try to silence or intimidate their critics make themselves stupider, almost as if they are shooting darts into their own brain.

In his book The Constitution of Knowledge, Jonathan Rauch describes the historical breakthrough in which Western societies developed an “epistemic operating system”—that is, a set of institutions for generating knowledge from the interactions of biased and cognitively flawed individuals. English law developed the adversarial system so that biased advocates could present both sides of a case to an impartial jury. Newspapers full of lies evolved into professional journalistic enterprises, with norms that required seeking out multiple sides of a story, followed by editorial review, followed by fact-checking. Universities evolved from cloistered medieval institutions into research powerhouses, creating a structure in which scholars put forth evidence-backed claims with the knowledge that other scholars around the world would be motivated to gain prestige by finding contrary evidence.

Part of America’s greatness in the 20th century came from having developed the most capable, vibrant, and productive network of knowledge-producing institutions in all of human history, linking together the world’s best universities, private companies that turned scientific advances into life-changing consumer products, and government agencies that supported scientific research and led the collaboration that put people on the moon.

But this arrangement, Rauch notes, “is not self-maintaining; it relies on an array of sometimes delicate social settings and understandings, and those need to be understood, affirmed, and protected.” So what happens when an institution is not well maintained and internal disagreement ceases, either because its people have become ideologically uniform or because they have become afraid to dissent?

This, I believe, is what happened to many of America’s key institutions in the mid-to-late 2010s. They got stupider en masse because social media instilled in their members a chronic fear of getting darted. The shift was most pronounced in universities, scholarly associations, creative industries, and political organizations at every level (national, state, and local), and it was so pervasive that it established new behavioral norms backed by new policies seemingly overnight. The new omnipresence of enhanced-virality social media meant that a single word uttered by a professor, leader, or journalist, even if spoken with positive intent, could lead to a social-media firestorm, triggering an immediate dismissal or a drawn-out investigation by the institution. Participants in our key institutions began self-censoring to an unhealthy degree, holding back critiques of policies and ideas—even those presented in class by their students—that they believed to be ill-supported or wrong.

But when an institution punishes internal dissent, it shoots darts into its own brain.

The stupefying process plays out differently on the right and the left because their activist wings subscribe to different narratives with different sacred values. The “Hidden Tribes” study tells us that the “devoted conservatives” score highest on beliefs related to authoritarianism. They share a narrative in which America is eternally under threat from enemies outside and subversives within; they see life as a battle between patriots and traitors. According to the political scientist Karen Stenner, whose work the “Hidden Tribes” study drew upon, they are psychologically different from the larger group of “traditional conservatives” (19 percent of the population), who emphasize order, decorum, and slow rather than radical change.