Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Strigops habroptila

By Kimberely Collins, CC BY 2.0

Etymology: Owl Face

First Described By: Gray, 1845

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Neoaves, Inopinaves, Telluraves, Australaves, Eufalconimorphae, Psittacopasserae, Psittaciformes, Strigopoidea, Strigopidae

Status: Extant, Critically Endangered

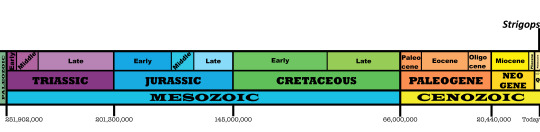

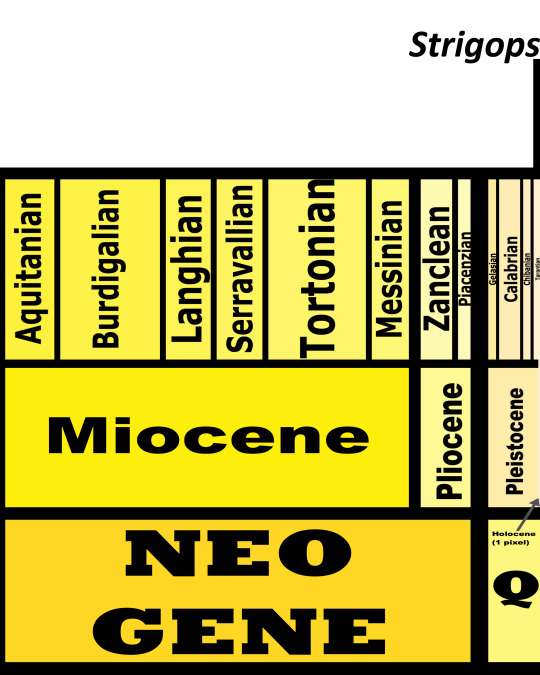

Time and Place: From 12,000 years ago to today, in the Holocene of the Quaternary

The Kākāpō lives entirely within New Zealand

(Green shows the Maximum Distribution known; yellow fossil evidence. By Msikma, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Physical Description: The Kākāpō is probably one of the most visually distinctive birds, being a giant lump of a parrot! They get up to 64 centimeters in length and weigh up to 3 kilograms just to be extra. They are rotund to the extreme, with males larger than females; they are green in color, with brown stripes on their wings leading back to the ends of their wings and their tails. They have more of an olive color on their chests, and brown on their faces, with lime green stripes across their eyes. Their beaks are basically invisible, constantly surrounded by feather fluff. And, what’s of extreme importance - they can’t fly! They’re too big! And their wings are quite short indeed - they have the smallest relative wing size of any parrot! Instead, they use their wings to break their falls when landing from trees. They are also able to accumulate a lot of body fat, unlike other birds. Females are also different from the males in having more of a narrow head and beak.

By Mnolf, CC BY-SA 3.0

As babies, the young are covered in white down, and become fully feathered after seventy days. The juveniles are then more of a dull green with more uniform bars of black across the feathers. These birds have extremely good senses of smell, able to distinguish between different things by smell while foraging. They are also nocturnal, and able to see well in the dark, but they have poor vision during the day. Unfortunately, due to their extreme genetic bottleneck, the Kākāpō are extremely inbred and have high disease rates and fertility problems in Kākāpō young.

By The Department of Conservation, CC BY 2.0

Diet: Kākāpō are vegetarians, eating a wide variety of fruits, berries, nuts, seeds, greens, shoots, roots, tubers, barks, stems, moss, and even fungi; which they grind up very finely with their beaks.

Behavior: Kākāpō, like most New Zealand Birds, are essentially built to be some sort of Bird Rabbit, given the absence of mammals on the island (except for bats) prior to human settlement. These birds are excellent climbers, going up into trees and spreading their wings to parachute down to the ground. Then, on the ground, they use their strong and stout legs to move around and look for food in the leaf-litter. They jog a little across the ground, moving in a relatively limited range in order to find food. These are very curious birds, and not stupid - they were the third most common birds in New Zealand prior to human arrival, able to avoid a wide variety of dinosaurian predators. To do so, the Kākāpō evolved to be nocturnal - in direct conflict with the diurnal lifestyle of Eyles’ Harrier and Haast’s Eagle. They weren’t entirely safe at night, given the presence of the Laughing Owl - their main predators - but they were still mostly able to avoid them. The males make loud booming sounds at night which continue for hours - and even hoot to attract mates! All sexes make loud, high-pitched squeals, skraaaks, growls, and croaks.

By the Department of Conservation, CC BY 2.0

Kākāpō do not form pair-bonds while mating, and the males fight each other in order to attract females. The females listen to the males while they display (“lek”), making Kākāpō extremely unique - they’re the only parrots that do this. The males leave their home ranges for the hilltops in order to join these fights, fighting with raised feathers, spread wings, open beaks, raised claws, screeching, and growling. These fights are no joke but can harm and even kill the other Kākāpō. This event occurs only once every five years - usually influenced by the presence or absence of suitable food. The male, arriving at the lek, digs a bowl in the ground, usually big enough to fit the entire bird. These bowls are made next to rock faces, banks, and tree trunks. The males clean the bowls thoroughly and then attract the female with low frequency calls that can attract competition from other males. The females are attracted to these competing songs, walking several miles to reach the males.

By Mnolf, CC BY-SA 3.0

The males then display by rocking from side to side, making clicking noises with his beak. He then turns and walks backwards towards her, and they may mate for as long as forty minutes. The female then returns home to lay eggs, while the male returns to his lek to try and attract another female. The female lays one to four eggs, which are incubated for about a month. During this time, the female guards her nest the entire time, except for when she has to go and find food. Upon hatching, the chicks are extremely vulnerable to predators; the mother will protect them until they fledge at three months after hatching. They are never fed meat, only plants, by the mother. They finally leave the mother at six months of age. Males reach sexual maturity at 5 years, while females reach sexual maturity between four and nine years of age. Prior to this time, they’re teenagers, and will even play-fight with each other! They do not breed every year, and have some of the lowest rates of reproduction. They tend to produce more males when conditions are good, and more female babies when conditions are more dire.

By Brent Barret, CC BY-SA 2.0

Ecosystem: These birds mainly live in forests, especially near river flats and in sub in the low mountains. They shelter in low trees, burrows, shrubs, and crevices at night, before emerging during the day. Today, Kākāpō are kept protected; in their natural ecosystem, they were mainly hunted by owls. In between, they were in danger due to humans, cats, dogs, and a wide variety of other introduced mammals. This also forced them into other habitats, making them what is dubbed as “habitat generalists” as they can be found in other places besides the forests, including mountain beech and totara forests.

By the Department of Conservation, CC BY 2.0

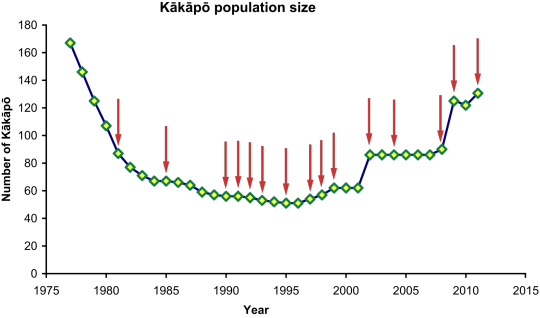

Other: Unfortunately, the Kākāpō is on the verge of extinction, and this is entirely down to the effects of European settlers on the New Zealand islands. Prior to any human arrival, Kākāpō were the third most common bird on the islands, widespread across them. Upon the arrival of the Polynesians, they did decline sharply, as they were easy prey for humans and dogs due to their lack of flight. Still, the Kākāpō had stable populations and no genetic bottleneck, until white men came along. Upon the arrival of European settlers, the huge influx of dogs and other mammal predators such as cats, rats, and stoats, caused a very dramatic decline in the population of these birds. Then, people there found them to be a curiosity, and killed them and captured them for zoos and collections - if they were alive upon capture, they died very quickly. Starting in the 1870s, the colonizers were most concerned with collecting as many specimens as they could before the Kākāpō became extinct - especially when large numbers of mustelids were introduced to reduce rabbit numbers and had the unfortunate side effect of preying on the Kākāpō.

By KimvdLinde, CC BY-SA 3.0

Conservation efforts began in earnest at the turn of the century, with nature reserves being established, especially on Resolution Island; an invasion of stoats lead to that particular population collapsing almost immediately. Some refuge populations still existed on the South Island in the first half of the 20th century, but by the 1950s the situation was extremely dire for the Kākāpō. At this point, the New Zealand Wildlife Service began making expeditions to find Kākāpō; these trips were largely unsuccessful, and by the 1970s it was uncertain if Kākāpō were still extant. A bird was sighted on Stewart Island, and a trip to the island located a few dozen Kākāpō - estimated at 200 years. Feral cats present on the island were killing Kākāpō at a rate of 56% a year, and intensive cat control was imposed. However, the birds were transferred to entirely predator free islands, and a conservation recovery program was instilled in 1989.

By The Department of Conservation, CC BY 2.0

These programs were especially tough, as feral cats kept appearing everywhere on the islands selected for conservation. Eventually, in 2005, all Kākāpō were transferred to Anchor Island. The Kākāpō are monitored extensively, with supplementary food given to increase plant, protein, and seed content. The feeding does affect the sex ratio of offspring, and the conservation reserachers use that to increase the number of female chicks. The food eaten by the Kākāpō is monitored closely to make sure that optimum health is maintained.

By the Department of Conservation, CC BY 2.0

Kākāpō numbers have been steadily increasing, with adult survival rate and reproductive rates increasing every year. However, no Kākāpō have been able to be introduced to islands to form stable populations on their own without monitoring. Resolution Island is currently in the process of being prepped for Kākāpō to be reintroduced upon reaching a population with 150 breeding females. As of 2019, Kākāpō have had the best breeding season on record, with 46 chicks hatched as of March 1 - this is the earliest, and best, breeding season seen in the entire program, leading to some hope for the situation!

By Mnolf, CC BY-SA 3.0

To learn more about the Kākāpō (and even adopt a bird!), go here: https://www.doc.govt.nz/our-work/kakapo-recovery/

Together, we can protect this unique and sweet species of bird.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

Keep reading

353 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Workin’ on a batch of raptors but here’s an Ace Brachio helping an Aro Stego paint their plates for pride 🦕

898 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I initially wasn’t going to do a gay pride flag dino, mainly because it has so many colours and I wasn’t sure how I was going to fit them all on one dinosaur. But considering what happened in Orlando, I thought I’d give it a shot. I know the community likely needs a boost.

This is a Diplodocus, since it was big enough that I could fit on all the colours without it looking too crowded. Unfortunately it is also so big that all detail is lost and would have been pointless, so they’re very simple looking. I included a close-up, just so you could actually see the face and head.

Stay strong and stay brave guys.

@a-dinosaur-a-day

225 notes

·

View notes

Text

Worldbuilding June 2019 Episode 3: Sapient Species

3. Who lives in your world?

Once upon a time, a strange group of apes began walking bipedally. Meanwhile, on the other side of the world, a group of paravians were pushing themselves towards increasingly elaborate social displays of skill and creativity, and wound up self-selecting for intelligence as a side effect.

Enter the Droman:

Ouranodromeus artifex

Height: 1m Weight: 20kg Classification: Maniraptora, Paraves, Troodontidae, Neotroodontidae, Dexteropterygidae, Sapiornithoides

The Droman (Ouranodromeus artifex) is a mid-sized, advanced troodontid that is noteworthy for possessing intelligence on par with humans. Having evolved from a volant ancestry, young dromans retain a limited flying ability that is lost when they mature as the arms shrink relative to the body and the primaries recede from the distal end of digit II.

The wide array of aerial adaptations that dromans posses, despite a recent evolution towards increased size and hand dexterity, have allowed them to invent self-powered flight augmentations. This was the most groundbreaking turning point in their culture. This allowed them to open trade and communication throughout all their peoples and it’s the reason why there really is no such thing as “remote” in their half of the world.

Dromans are hypersocial and nearly all aspects of their society revolves around one single ideal: showing off. They paint and decorate themselves obsessively, and reinvent their appearances constantly. Their society is obsessed with the arts, to the point that most other fields of study are considered boring (much to the chagrin of dromans in those fields). There’s a social expectation that your appearance should reflect on your personality, interests, and skills, and failure to do so is generally treated with disdain. In short, dromans are incredibly vain an flighty, and their attention easily caught by whatever is new and interesting. They tend to pick up new hobbies and interests constantly, and drop them just as quickly–it’s rare to meet a droman who would devote their entire life to one pursuit, and they tend to find it rather strange that humans are so prone to doing so!

I have a lot, lot more information on them (they’re basically the only part of this world I’ve put any thought into), but I’ll save the details for each specific day.

33 notes

·

View notes

Photo

tree ferns at russell falls, mount field national park

7K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Snorlax for @.Texasdave_94 on Twitter!! ☕

16K notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Demolition”

My new print for Sonic Revolution this weekend, featuring my favorite new gals from the IDW Sonic comics!

Support on Patreon for early access to new artwork and receive other rewards such as art postcards and sketches!

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

*comes online*

*reblogs 30 things within 5 minutes*

*fucks off again*

614K notes

·

View notes

Video

Meet Lucky, your partner and pet parasaurolophus! She will be your trusty steed as you explore the wilds and encounter new dinos in our upcoming dino game. 🦕 🍃 🦖 Animation by: Alan Martin Model by: ItsLocko Production by: ItalicPig 🌿 Follow me on twitter for more updates: Here 🌿

19K notes

·

View notes

Text

Come join ArkFriends:3

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

What John Hammond and InGen did at Jurassic Park is create genetically engineered theme-park monsters. Nothing more and nothing less.

Jurassic Park /// (2001) directed by Joe Johnston

635 notes

·

View notes