Muffled sounds echo. Composer, Game Developer, Writer, Visual Artist, etc. he/himvisit brukholevin.com for more information

Last active 60 minutes ago

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

In Two Places at Once; or, "How's My Gimmick? Call 1-800-XXX-XXXX"

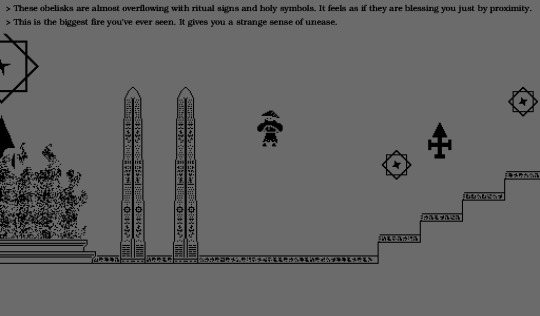

It's no big secret that Kenoma's main gimmick is the whole "two worlds" thing. Other games have done it, most prominently Titanfall 2 ("Effect and Cause" even has its own Wikipedia page!), but I believe Kenoma's visual style and 2D nature allow for a more unique twist on the concept. It's hard to layer two 3D environments on each other visually in a way that both makes sense, and conveys useful information. And a sparse 2D style ensures you can see most, if not all, of what's happening to you at any given time.

The grey terrain and buildings are in the 'other world', and are currently intangible.

This concept and implementation, like any other, has a unique set of limitations and freedoms, and tools and tricks to use. Exploring the depths of these various idiosyncrasies is both interesting (at least to me) and worthwhile as an exercise, because any example is full of useful lessons that can be applied broadly. I'd also like to explore how well and poorly I use this concept's unique strengths and weaknesses, for approximately the same reason.

To start with, there are plenty of things you can do with this kind of two-phase environment in terms of platforming gameplay. On/Off blocks (or P-Switch blocks) in the Super Mario games are directly comparable mechanics, and these have been part of the series since 1988. Effect and Cause also has you jumping around while time-hopping, leaping from the past and landing in the future or vice versa. The unique power of Kenoma here is that you can trigger a change whenever you want and have clear, total understanding of your surroundings in both worlds at all times.

In a game focused on platforming, this could enable all sorts of nonsense. The limit would ultimately have to be how much mental space a player would have to do both the world-swapping and platforming at the same time. Imagine having double jumps, wall-jumps, air-dashes, and an array of surfaces to stand on that all behave differently (slippery, sticky, timed-disappearers, spike pits, etc). But Kenoma is not focused on platforming: to me, it is a means to an end. So I content myself with smaller, simpler environments that make sure players are thinking in terms of both worlds, but don't contain enough challenge to take focus from what matters.

Which, of course, is the narrative and "adventure game" puzzle structure (see [this] post for more thoughts on that). This is where my integration of the two-worlds into the gameplay structure really matters, and needs to feel necessary. Otherwise it will come off as weird, useless, and worthless. A waste of the game's time, so to speak.

Narratively, I believe I couldn't possibly have failed at this. The game's core narrative concept is so woven into the two-world structure that it would have to be extremely poorly-written to fail at integrating itself into it. Even as my perspective on my work isn't the most charitable, I can recognize that it isn't as bad as that. Every character interacts with this core issue, presenting some unique element to grant the player an extra perspective on the game's world.

It's not done in so many words either: each character has their own relationship to the world that feels (to me, at least) natural and sensical. It's like how all people in the real world have a relationship with gravity, or electricity. It doesn't define us, but it does create the world we experience and help to shape what we become.

In terms of adventure-game style puzzles, I feel there's a good amount of integration here as well. Both in terms of added convenience where it has a direct analogue in other games without the gimmick, and unique solutions to problems enabled by the gimmick.

Having two worlds isn't in and of itself different from having one world that is twice the size. For example, the difference between having to travel between two towns to solve something in Kenoma and in a more traditional single-world game is small. In Kenoma, you press the "switch worlds" button. In the other game you'll have to walk, or pass through a loading screen via fast-travel. There's something to be said for the tight, compact design Kenoma's worlds enable, but it's not a major structural difference.

Where the difference really shines is in the written "rules" of the two worlds being different. One might be able to have an eternally abundant and ancient source of water, but be unable to light new fires without magic; the other might find lighting fires incredibly easy, but have no sources of water that do not dissipate. When one world never changes and the other is made of nothing but change, it pays to be able to switch between them. And I believe this is fairly thoroughly explored in the design Kenoma has wound up with.

But there is something I think is ignored, perhaps to a detrimental degree: core system interactions. Things like your movement mechanics, the inventory system, and interactible objects. Kenoma does poke at this a little. Some items change when you swap between worlds, for instance, and there are different forces that act on these objects in different worlds (at least narratively).

There could be so much more that interacts with this. Imagine if the different worlds had different kinds of momentum, varied gravity values, or even inverted gravity. There could have been structures that exist in both worlds, but have different forms depending on which world you're in. Perhaps one world could implement a stamina system and the other a HP system, and traveling between the worlds could take a resource, such that you could be temporarily stranded for some more isolated challenges.

Of course, ideas such as this can flow quite freely when you aren't on the hook to implement them. And ultimately, Kenoma is not about the ludic implications of a world like this, but about the narrative ones. The gameplay is there to facilitate the story, and to make it more interactive. Several of the above ideas would also be difficult to implement without making the game bad, or at least difficult to control. Yet it does signify a significant design space I neglected.

Perhaps a more gameplay-centric version of this concept could serve as a sequel? Though, I'd imagine the crowd interested in Kenoma isn't necessarily interested in a precision-platformer or some such. And where the Hell could the plot go? Much to consider.

* * *

BrukhoLevin Mailing List: https://www.brukholevin.com/mailinglist.html

KENOMA on Steam: https://store.steampowered.com/app/2933260/Kenoma_Action_Without_Action/

KENOMA on itch: https://brukholevin.itch.io/kenoma-action-without-action

KENOMA press-kit [for journalists]: https://www.brukholevin.com/kenoma_presskit.html

#blog post#game design#gamedev#someday i will make something based on pure twitch-reaction instinct#but not today

0 notes

Text

Readable Esoterics, Findable Solutions

Kenoma is a game without combat, and where moment-to-moment traversal is at most a minor obstacle. So, the core obstructions keeping you from your objectives have to be puzzle-based. Not necessarily something like a Resident Evil puzzle, where you have to find the solution to some spatial reasoning thing (e.g. rotating hexagonal tiles), but having a problem and needing to find a solution using what's available in the area. More along the lines of classical adventure game puzzles, like stopping a steam leak with a monkey wrench. These are both more interesting to me in the long term and easier to find a place for in a game's progression, so Kenoma is full of them.

All puzzle design needs to balance readability with esotericism. If a puzzle is too esoteric, no one can ever figure out how to solve it. A lot of older adventure games fall into this, either because they wanted you to get frustrated and pay to call their tip line or because it was the style of the time. On the other hand, if your puzzle is too readable, then there's no actual puzzle and it gives no satisfaction in the solving.

Traditional "mechanical" puzzles, like jigsaws and Rubik's cubes (and those Resident Evil puzzles) have a built-in avoidance of this balancing act: the exact sequence of actions needed to solve the puzzle is unknowable. Even with algorithms or guidelines in mind to make the act of solving more efficient, there's still the journey of getting to the known states you're looking for. You still need to find and attach the edges of the jigsaw to each other correctly, you still need to figure out how to get the white cross on the top of the Rubik's cube from its scrambled state.

Adventure game puzzles don't have this. So, they must generally lean towards a more esoteric structure. An oft-used tool in the adventure game structure is "lateral thinking", or "thinking outside the box". For example, using a crowbar to reach a far-off object rather than to open some sealed container. This is a blessing and a curse, because it can be either far more rewarding than any other kind of puzzle, or far more disappointing.

If you can figure out the designer's intent, then you feel like you've solved a problem in a more real sense than a more mechanical puzzle. This kind of puzzle approximates using your ingenuity and smarts to solve a problem in the real world, which is inherently satisfying. Disappointment creeps in when there's a gap in the designer's mental leaps and the player's. No one can count for the infinitely many possibilities of real-world problem solving in a video game, so the solutions you envision as a player can be completely different from anything the designer was envisioning. This disconnect sucks for everyone. I find the best ways to avoid this are clever visual design and foreshadowing.

"Clever" visual design is easy to explain: if an object stands out, it will draw attention. This will make it easier to remember, consciously or unconsciously, for any player that sees it. They can then remember it when it might be useful and seek it out. That is, if it wasn't immediately retrievable. What amount of cleverness is actually in any individual instance of this design tool is up to interpretation. But if it gets a player to remember something important, then what else matters?

Here, one might ask: "why are all the chairs in this room different?"

Foreshadowing is a little more convoluted: show an item/object/system/etc working in some way, then later have the player need to create something similar. An example from Kenoma: early on, the player may interact with a "bag of winds", like the one Aeolus gave to Odysseus (or Mindy gave to SpongeBob, if you prefer). Later on, there may be winds blocking your progression and an empty bag just waiting to be filled. The hope is that players will remember the earlier bag and seek to recreate it, having been successfully "primed" to think of that as a possibility.

This method does have issues. Firstly, in a game where your choices can dictate what puzzles you interact with, the foreshadowing can fall flat. The above example isn't guaranteed to happen, for instance. Secondly, if your "setup" is too far from the "payoff", you risk players forgetting the connection. And in a video game, there's no good way to ensure the setup and payoff are close enough together to ensure they connect. The player is the ultimate arbiter of the game's pace, after all. Still, this is one of the most rewarding feelings you can give to a player with an adventure game puzzle. It's the best approximation I can imagine for genuinely solving a real-world problem. Accordingly with these issues and payoffs, it's a good tool to use sparingly.

There is one final tool that I feel is indispensable here: the accidental solution. More exactly: letting player find the solution to a puzzle by chance, before they encounter it. This isn't always possible, and letting it happen too often would cause a lot of issues with puzzles being too readable. But when it's reasonable, do it. Having what you need to solve a puzzle right when you finish looking at it rewards a player who takes time to explore and find all their options beforehand. If one can't solve anything before seeing it because of arbitrary progression gates, then you risk a player who wants to do that kind of thing getting discouraged, losing the desire to investigate and poke around. This can lead to people checking out and even giving up on playing the game, because it's excluding their method of play.

Of course, puzzles are not the only thing in Kenoma. A game cannot run on brain-teasers alone. But they are what I had to spend most of my time thinking about and implementing, so I feel they deserve at least this much examination (if not more). You would be surprised how straightforward it was to implement everything else around them.

* * *

BrukhoLevin Mailing List: https://www.brukholevin.com/mailinglist.html

KENOMA on Steam: https://store.steampowered.com/app/2933260/Kenoma_Action_Without_Action/

KENOMA on itch: https://brukholevin.itch.io/kenoma-action-without-action

KENOMA press-kit [for journalists]: https://www.brukholevin.com/kenoma_presskit.html

0 notes

Text

How Does an Unreal World Sound? (Music, Effects, Abstraction)

In a utilitarian sense, music and sound effects are tools. Their use is to set tone and provide feedback to player actions. The right music underscores and surrounds both the narrative and game-play, bolstering the intended mood of any given moment. It can also be feedback in terms of winning or losing, as with Final Fantasy's "Victory Fanfare". Sound effects have less nuance: they're better for direct feedback when the player does an action. Swinging a sword needs a whoosh, breaking a pot needs a crash, and so on. Having the right sound effect at the right time can make the difference between feeling like nothing happened and feeling like your actions have had consequences.

So, what are the "right" sounds for Kenoma? Between music and sound effects, the latter is much simpler to figure out. Yet it has more immediate nuance in its design.

Kenoma is not trying to present a realistic environment. One look is all it takes to know this. Abstraction is the name of the game visually, and so it should be the same in terms of sound effects. The impression of sound, not necessarily what something would 'really' sound like. Most video games have sound effects of this ilk already: there is no special sound for jumping in real life. But even deep into abstraction, some core of the real sound must remain. Otherwise, how else can you know what it represents?

There are two basic 'tricks' to Kenoma's sound effects: white noise and rising or falling tones. They combine in various ways, or sometimes remain totally separate, to produce almost all the sound effects in the game.

White noise is purely atonal and can cover the entire spectrum of audible sound. This means that it's everywhere in the real world, and most sounds have some of it in them. So when making a sound from first principles, this is usually the "anchor" that binds it to reality. It's therefore a powerful tool in Kenoma's belt, and has a presence in many of the sound effects. Most impact sounds, the low rumble of a fire, explosions, wind, and so on, are primarily driven by white noise.

Rising and falling tones are more abstract; they play on our proclivities for pattern recognition and some kind of inherent capacity for metaphor. People generally expect a rising tone to indicate something turning on, entering, or otherwise some kind of beginning. A falling tone indicates the opposite. Pac Man's mouth opening and closing has a rise-fall-rise-fall audio pattern, for instance. I don't really know why people expect this, or why it's fairly universal. But it works, and so is an integral tool for more abstract sound. Kenoma utilizes it for entering and exiting buildings, jumping, opening a small cage, uncorking a pot, and so on.

In terms of music, we're in a less utilitarian space. The music must convey the proper emotion of any given scene, but it also needs to feel right. To match with the visual aesthetics seamlessly. String quartets do not quite match with Super Metroid, do they?

So what fits Kenoma? The music should be sparse and stark, for one. That's the best way to match to the core visual style. And there should be a casual depth to it, both intricate and able to wash over you. This so that it both fits the visual-asset design and so that it looping tens of times does not start to grate on people. There are a few genres of music that fit this description, so I decided to combine aspects of several: ambient, minimal synth, and dub.

Ambient comes in to provide a structural backbone. Partially so that there is always some sound, because having a score typically means not having ambient sound effects, and partially because of it being a good general fit for soundtrack music. These ambient structures are derived primarily from Music for Airports, where much of the intrigue comes from asynchronously looping progressions. To achieve this in a digital context, Kenoma's music often plays with time signature and 'riffs' (to borrow a rock-and-roll term) of varying length. Elements of each song therefore go in and out of phase with one another while the whole remains cohesive.

Dub is primarily present in the bass and accent-notes of the music. It brings both a staccato, spacy feel and a real swing to the instrumentals, keeping them from becoming tasteless and monotonous. With the bass taking such an active role, most of the other parts are able to take a more floaty and ethereal approach. They follow along with the pacing and structure the basslines provide, but remain generally ambient in nature. The bass being so large and forward in the mix makes for a clear audio parallel to the large amounts of empty space on screen at any given time.

Minimal synth is the final secret ingredient of this soundtrack. If everything I've said before was done using real-world instruments with a huge budget for production, it would feel odd playing over these rudimentary pixelated environs. By using unadorned, simple sounds that come straight out of a synthesizer, everything coheres beautifully. This choice also drove me to the core self-imposed limitation of Kenoma's soundscape: all the audio in the entire game was made with a single software-synthesizer. The bass, the pad, the percussion, even all the sound effects.

A final thing I'd like to discuss that make's Kenoma's sound somewhat unique: unaltered sine waves. Most music does not utilize pure, unfiltered digital sine waves. In most circumstances they are rather flavorless, and at best typically come out sounding like a hitherto unknown woodwind instrument. But for Kenoma, that flavorlessness is exactly right: we need as much intrigue as possible without distracting the player. Plus, their rarity elsewhere gives an excellent boost to the "weirdness" factor of the soundtrack.

In the interest of transparency, much of this is a post-facto examination of the final shape the audio of Kenoma has taken. In the moment it's more a process of feeling things out, much more iterative than what it might seem as detailed here. However, I did make these choices for tangible reasons. And though I did not iron them out in a clear and concise list, they were essentially the same as what's described here. Just messier, less easily understood. I believe it all comes together to form quite the cohesive whole.

* * *

BrukhoLevin Mailing List: https://www.brukholevin.com/mailinglist.html

KENOMA on Steam: https://store.steampowered.com/app/2933260/Kenoma_Action_Without_Action/

KENOMA on itch: https://brukholevin.itch.io/kenoma-action-without-action

KENOMA press-kit [for journalists]: https://www.brukholevin.com/kenoma_presskit.html

1 note

·

View note

Text

Fact, Fiction, Action Without Action

There were two extra-narrative guiding principles I kept in mind while writing for Kenoma. Around every story beat, every character, every word, these were there: no allegory, and no literalism. I believe i kept to these principles well. Kenoma has no thematic or narrative ties to an older, different story that are used to reinforce the narrative I want to convey (or vice versa). Nor does it portray itself as literal telling of real events; there are intentional moments of inauthenticity, directness, and certain gaps in the presentation's facade that hopefully make it clear, even on a surface level, that there is no "reality" in the world around you. Nothing to arrange into some sort of solved history.

How much more obvious could this be?

My reason for this is rather simple: I hate allegory. I hate literalism. They have no place in fiction, detract from its unique gifts, and serve only to waste the space they take up. Be that on a page, a screen, or in RAM.

Fiction is primarily interesting for its ability to offer that which does not exist. You can have any experience the human mind can conjure, without having to suffer the negative consequences it would bring if it were real. And these experiences have inherent meanings: fiction does not exist without having something to communicate. However profound or shallow that thing might be.

The only other category of writing is nonfiction, which is clearly an obverse. Nothing that happens in nonfiction has any inherent narrative meaning, nor does it exist to communicate a specific thing. Events simply occur. Of course, there is a chain of cause and effect. There are lessons to be learned, interpretations to be made. In fact, these lessons and interpretations are far more important than anything fiction provides. And unlike fiction, there is infinite depth to each event.

But you can't play with nonfiction. Try to twist or bend it and it becomes fiction. This is not the case in the other direction: a winding tale cannot be made into a fact no matter how much you try to straighten it out. This is the real power of fiction, in my eyes. You can do anything to it, and turn anything into it. An infinitely tensile material that you can stretch, bend, expand or contract, even cut and tear without breaking. There is endless freedom in fiction.

It is for this reason i hold hate in my heart for allegory. Taking a new fiction and restricting it to the themes and messaging of one pre-established, or shackling it to nonfiction, is a total rejection of that freedom. Why tell this new story, if you want it to be the same as something already extant? Just tell that one again. And if you take your story in a different direction from your allegorical subject, then why did you choose it in the first place? Once you have your allegory, you are on the hook to deliver those same themes and messages. No matter what the story you tell comes to be about.

My hatred for literalism is more convoluted. Literalism engages with fiction, takes it in, and then ignores all the elements that make it fictional. In a literalist framework, fiction is no different from nonfiction. It has no inherent meaning, no theme, no narrative flow. Simply a set of causes and effects, that may be analyzed only to guess what comes next or learn something about the wider fictional world. This is so clearly counter to what fiction offers that I cannot understand it as a perspective. I want it as far away from me and my work as possible, and fundamentally do not respect it.

This is not to say that the underlying impulses behind allegory and literalism are bad. Taking inspiration from art that has come before yours, or finding similarities between two works and examining them under that lens, are not bad things. No art is free of the influence of what came before. Recognizing these inspirations, and examining the ways in which works differ, is an excellent tool for analysis. Nor is a story that uses the structures and aesthetics of literality, as in a historical document, inherently bad. It is only when the story being told is eclipsed by its inspirations, by that hunt for plain causality, that things turn to shit.

Which is why I decided to build Kenoma to an anti-allegorical, anti-literal standard. These two tenets aren't the bedrock of the concept -- you can't build something just by choosing what not to build -- but they guided the construction as it progressed from cornerstone to chimney. As such, the result is a hopefully interesting blend of inspirations untethered to their sources, free from a fact-first framework. Narrative built of theme, mood, and words that evoke their own set of thoughts and emotions; unlike any single thing that came before it in at least one way.

* * *

BrukhoLevin Mailing List: https://www.brukholevin.com/mailinglist.html

KENOMA on Steam: https://store.steampowered.com/app/2933260/Kenoma_Action_Without_Action/

KENOMA on itch: https://brukholevin.itch.io/kenoma-action-without-action

KENOMA press-kit [for journalists]: https://www.brukholevin.com/kenoma_presskit.html

0 notes

Text

Background, and the Notes You Don't Play

If a game takes place in a world that's not our own, one concept tends to dominate the discussion of its plot: lore. What has happened, what has been prophesied, who did what, where, and why. This is understandable: a great deal of theme and narrative setup can be crammed into ambient text like item descriptions or in-game books. And people like deep worlds. When the author has put some meat on those narrative bones, it's naturally engaging.

There is a temptation within this to reveal all. You wrote it, so you should put it somewhere, right? In a book off in the corner, or in the text of some obscure side-quest. This is one of the most destructive thoughts you can have. Fiction is not a textbook: it needn't explain every little thing. Allow some mystery to creep in, and people will take your background world more seriously. Leaving gaps lets people wonder.

In and of itself this is an enjoyable way to interact with fiction, but it can also lead to gap-filling. People naturally want to understand things, solve mysteries. If you leave a few breadcrumbs out, whether they lead to an answer or not, people will pick up on them. Consciously or not, they'll put together something that seems connected by the patterns they notice. That something will be tailor-fit to their preferences and interests, because it's their own work. In a sense, the gaps encourage a kind of long-distance collaborative storytelling.

To me it seems that the most obvious example of this structure is the Souls games. There are so many holes in those worlds that you could fill a suite of night classes on interpreting them and figuring out how to connect the disparate pieces. This is, rightly, a well-observed phenomenon. However, the extent of it has a big drawback: with so many holes in such important places, people feel compelled to "solve" the narrative. It leads to people taking conclusive, sure stances that sound less like interpretation and more like a list of historical events.

The way to keep this from happening is to keep the uncertainty simmering beneath whatever plot threads are occurring. Your goals must be concrete and clear, but the rest can be as muddy as you want. A good example of this approach is the main-quest of The Elder Scrolls III: Morrowind. There is virtually no certainty, no clear unbroken fact in any of the setup. Whether or not you're a hero of legend, what exactly that would mean if it were true, who caused all the mess you have to deal with in the first place, what it means for the broader setting. All incredibly unknowable. But since you have a clear goal at every step of the way, the noise of confusion washes into the background. It becomes stage dressing, something to think about a bit as you wander towards your next objective. Players aren't expected to puzzle out what the goal is, they're expected to kill the evil god living in the volcano.

Kenoma has the same core expectation of players. By the time you're really interacting with the pieces of the wider world I've strewn about, your main goals are clearly-defined and easy to focus your efforts on. There is a difference, however, in the structure's use. Morrowind uses uncertainty to add intrigue to the main questline, within a larger world that is more or less explicable. In Kenoma, much more of the setting itself is left implied. Fossilized, in a sense. Composed of ancient fragments that gesture to a complete whole, but never quite tell you enough on their own. The most you'll get at once is a small piece, along the lines of this item description: "An alloy of tin and copper, made far sturdier by the forging process. Bronze has been symbolic of listless unbelonging and desolation for thousands of years."

Designing a world within this space is both restrictive and freeing. There is less total space for your world when it's intended to be filled with holes and implication, and you may have to cut elements that you find compelling. I've had quite a few ideas for interesting background groups and individuals that were cut, both for time and to make sure the vagueness remained intact. At the same time, the process of writing is often easier because you can just choose not to explain things. It's quite a nice option, especially if that thing has little relevance to anything you care about narratively.

But you must be judicious in what narrative you choose to care for. It's a delicate balancing act, both in detail and in tone. Leaning too far towards spurious or important information will leave the setting ill-defined and wasteful, or without any mystery. Too much frivolity or solemnity will make the setting seem weightless or joyless. Ideally, striking this balance presents a world that feels real without actually having to create every detail of such a thing. Could you imagine the work that would take?

As a side-note: the lack of explanation and intentional gaps in the setting have another, hidden advantage. Plot holes are often indistinguishable from intentional gaps. It's quite useful in later stages of narrative development.

One of the hardest things about a piecemeal setting like this is that you can't know how well it conveys itself as the writer. You know exactly how one is "supposed to" close the gaps, what was supposed to be in all the holes you've made. Do the pieces coalesce? Can people be expected to make the leaps of logic you're anticipating? They will, of course, always make ones you didn't anticipate.

The best way to answer this worry is to have someone else come along and figure it out for themselves. Seeing people experience your world is quite illustrative, and getting them to describe their idea of how the whole thing comes together is an ideal way to know whether or not it works. Hopefully Kenoma works. I believe it does.

KENOMA on Steam: https://store.steampowered.com/app/2933260/Kenoma_Action_Without_Action/

KENOMA on itch: https://brukholevin.itch.io/kenoma-action-without-action

KENOMA press-kit [for journalists]: https://www.brukholevin.com/kenoma_presskit.html

BrukhoLevin Mailing List: https://www.brukholevin.com/mailinglist.html

0 notes

Text

Making Ghosts: Player Character Evolution

In the previous post, I enclosed this image:

Drawn sometime in September of 2021, approximately a year before even the idea of Kenoma came to be.

This was the first depiction of what would eventually become the player character of Kenoma. At that point it was just a drawing; I never even expected it to have to walk, so practical concerns like animating it didn't much factor in. But when it came time to choose what the player would control, I had no other options available. So this had to do.

The initial character concept I decided to pursue was simple: there wasn't one. No name, no dialogue, nothing. Only a player avatar through which you experience the game world. At the time it felt right: a shapeless hero would allow players to more readily be themselves within the world. Reworking the design caused this to shift.

The artistic principles here are fairly basic, yet allow for a significant improvement over the prior design.

It is tempting to create a false narrative of 'the auteur' when detailing these things. Were it my aim, I could wax poetic about how the silhouettes compare or how the new design uses more shapes. But that is not my aim. This design was driven by practical concerns first and foremost. For instance: a character with 90% of their body as a single trapezoid makes for very flat and boring animations, so I opened the design up a bit. And I chose to clothe the character in a dress because it would let me avoid a "leg-driven" walking/running animation, which I felt would be impossible to make look good in the chosen style.

The design of the main character echoed through the rest of the art, informing the drafting process of every sprite and on some occasions being used as a literal measuring stick. Sometimes I would forgo this measure, realize something was too large or too small, and have to redo it entirely. In terms of character design, one of my largest takeaways was to avoid arms whenever possible. Draw cloaks, have hands floating, make things too abstract to even need them. This because, like legs, arms are very difficult to work in this style.

It was also here that I decided to make the protagonist a woman. At the time, I did not recognize this as the passing bell of the 'formless avatar' phase of her design. Looking back it's rather obvious. Defining anything about a player-surrogate will inevitably turn them into something else, because they can't be a surrogate if they have traits of their own. Especially in a game so text-heavy.

As stated above, this character initially had no character. But when a game is primarily composed of a specific character interacting with the world around her, she doesn't tend to stay that way. Even if you intend to be neutral, a character emerges in the dialogue responses you write. It's just impossible to avoid. Besides, it would be rather strange for one character out of the entire roster to have no traits. The player would feel a tension, an awkwardness about it. "Why am I so robotic?" or something of the sort.

Once I realized that there was, indeed, a character in my player character, I quickly settled on the classic 'nosy wanderer' as an archetype to shoot for. In this game the protagonist needs to be the kind of person who would, sight unseen, choose to throw her weight behind a cause because of the cut of a leader's jib, or because she has a gut-level preference for one side over another. Someone who would go into a home without invitation to poke around, or examine every corner of an old storeroom looking for anything hidden. And, of course, she must be strange. Strangeness goes hand-in-hand with being a wandering type: to choose or be forced into a transient lifestyle requires a certain detachment. Either as a gateway to the lifestyle, or as a coping mechanism in response to it. That detachment breeds a specific kind of oddity which is often useful.

A happy accident of this characterization is that an odd soul who says strange things is less likely to be seen by players as just an avatar, instead taking on a life of its own in their heads. This is good primarily because if I went to all this effort in characterizing the protagonist and people did not take note of it, I'd cry.

Finally: the name. Names are important, especially in fiction; they're the first impression and can be one of the most concise, evocative pieces of characterization in your toolkit. In Kenoma you can name the protagonist whatever you want, but a well-defined personality needs a defined name. And what fun is it if there's no default? I wavered for a while, but ultimately settled on "Ghost". This because of her transience, existence 'between' worlds, and because it has a nice ring to it. Synonyms for 'ghost' like 'phantom' and 'specter' were considered, but they all felt a bit too pretentious. Besides, 'ghost' is a much more visceral, much punchier word.

Ghost is, in a certain sense, the most important character in the story. She was one of the first designed, had a major influence on how the rest of the game came together, and as the protagonist none of this happens without her. In another sense, she's the least important character. You can't directly interact with her, she's not subject to a substantive narrative arc, and the player isn't likely to see her as something separate from themselves, something to be interacted with and explored. This is true of most player characters in most games, and hopefully means that the Ghost I've written will perform her function admirably. And who knows? Maybe she'll still leave an impression. * * *

KENOMA on Steam: https://store.steampowered.com/app/2933260/Kenoma_Action_Without_Action/

KENOMA on itch: https://brukholevin.itch.io/kenoma-action-without-action

KENOMA press-kit [for journalists]: https://www.brukholevin.com/kenoma_presskit.html BrukhoLevin Mailing List: https://www.brukholevin.com/mailinglist.html

0 notes

Text

Opening Crawl, A Brief History

Kenoma is in a somewhat unique position: at this point in the cycle, it is boring to watch. No major elements are being added or changed, the game is just being checked for defects. This will likely take a significant length of time in itself, and radio silence does not a successful release make. As such, instead of teasing development progress, these posts will wax over various details of the game, its design, and the history of such things.

To begin, I imagine it is best to explain where Kenoma has come from. It is a tangled mess of scrap, revived Old Ones, and ideas from the wider culture, as all works are. The concept has had four major forms, most of which were unnamed. For humor and organization, I will name them here: Redfire, Witchfire, Misfire, and Kenoma.

Something to understand before continuing: the core gameplay gimmick of the concept has always been a pair of "twinned worlds". This is what unifies these ideas as variants of the concept, rather than as totally different works.

⠀

Redfire

The initial design for the project that would become Kenoma was slipshod and half-baked. Redfire was conceived as a small project to occupy time between semesters of college, and to return to programming as passion rather than as assigned labor. The concept, however, set my mind aflame. Things quickly spiraled.

youtube

One of the only remaining vestiges of "Redfire" is this video of an early build. It never did get a graphical overhaul.

Redfire's final design intent before destruction is best conceptualized as The Red Book by way of Daggerfall. Jung's cosmology of the mind is certainly interesting, and has enough convolution to choke a horse. An excellent choice for aspiring mystics. This combined with the strangely intoxicating and mazelike dungeons of Daggerfall would be able to create quite the heady mix of esoterics and confusion. It would be almost impossible to leave 'unsolved' for a particular kind of player.

There were two primary problems with Redfire. First: it was too much work. Creating a 3D environment dungeon-crawler with enough inside to really justify its jungian premise is a job for a team of at least five, not for one person. That is, if it intends to be finished in less than half a decade. Second: Jung's Red Book is a compilation of the author's worst pseudoscientific nonsense. Compelling or not, using it as a basis without deconstructing it comes with the bedrock assumption that it is in some way accurate, truthful, or worth considering in its intended psychological context. Which it isn't. For these reasons, I abandoned this version of the concept.

⠀

Witchfire

Witchfire was a much shorter era of Kenoma's design history. It had no real gameplay, and was primarily composed of visual mockups and design documents. After abandoning the core concept of Redfire, this was primarily an attempt to produce a new, less 'icky' design. Consider it a transition fossil.

Witchfire's new direction was the initiation of several core principles that would make their way to the final product. The minimal pallet of the black-and-white entities seen in Redfire began their expansion to the environs here: changing from texture to flat-color. The narrative and setting were also put within the domain and whims of a god.

Witchfire is named for the 'tumblrcore' deer skull creature pictured here, intended to be the god whose domain you were exploring. Its name was "Witchlord".

Witchfire was created in free time, and as such had little elaboration in terms of game-play structure. The core intent was to turn things into a more traditional "adventure game", though little thought was given to it beyond that.

This was abandoned because it had very obviously grown beyond a manageable scope. The design began to shift towards a multi-archetype, rpg-adjacent structure similar to something like Diablo where you could be a wizard, knight, &c. An entire adventure game, structured to be completed in ways different enough to warrant character classes such as this, would not be something I could finish in a timely fashion.

⠀

Misfire

Of these concepts, Misfire is the least. No playable prototype was produced, no concept art was created. Yet it is one of the most consequential: it codified several of the core design structures that Kenoma would be molded by. The new core game-play would be along the lines of Zork in a 3D space, occupying a setting more like that of Dark Souls. Not in grimness or morosity, but in the shape of things. Confusion, interpretation, characters with adventures parallel to yours, and a depth built of true philosophy -- no bogus nonsense like that of Jung.

The primary work of Misfire was research. I read several philosophical and religious works during the Misfire era, to gain a clearer understanding of the kinds of thought that would be needed to construct such a world as is in Dark Souls out of whole-cloth. My ultimate takeaway was to abandon the idea of creating something totally new to base the world on. It would be too much work for too little payoff. Instead, I could take context-free pieces of all I had wriggling within my head, and smash them together into something that harkened back to the originals with a unique twist.

As a result of this, the current framing of "two opposed worlds" took shape. A struggle between gods is a fine mythic story beat, and adding a philosophical disconnect between them would ground it, make it far easier for a player to choose a side for a good reason, and thus become invested.

Misfire was abandoned for the same core reason as Redfire and Witchfire: its scope was too large. It was not subject to much scope creep; instead, I realized that a 3D environment game was either going to be too short for what I wanted to do, or take too long to make. And Misfire was not of interest to me in 2D.

⠀

Kenoma

Finally, here is the game as it exists. A mostly nonviolent Zork by way of Dark Souls, mixed heavily with questions of philosophy and religion. Consisting of approximately 60,000 words, several sprites, and at least a few lines of code. The core of the player's experience is their choice of immortality or mortality, an ever-compelling question to the existentialist within all of us.

Kenoma's one-bit visual style is primarily inherited from this image that I created far before the project began, which never truly left my mind.

You can read the marketing copy and store pages for a clear understanding of what the game is. Primarily, this post has attempted to explain what the game was, and how it became what it is. By sharing this, I hope to in some way illuminate process of constant iteration, inspiration, and alteration in art -- as well as to show that Kenoma is, if nothing else, a deeply premeditated work. Does that count for anything?

* * *

Please do not take the length of this post as an indication of the length of those to come. This is a much longer, more convoluted thing to explore than practically any other topic related to Kenoma. See you next week.

KENOMA on Steam: https://store.steampowered.com/app/2933260/Kenoma_Action_Without_Action/

KENOMA on itch: https://brukholevin.itch.io/kenoma-action-without-action

KENOMA press-kit [for journalists]: https://www.brukholevin.com/kenoma_presskit.html BrukhoLevin Mailing List: https://www.brukholevin.com/mailinglist.html

#gamedev#blog post#indie games#long#misfire was also responsible for the idea being “good enough” to move forward with#as more than a side project at least#Youtube

0 notes

Text

As gamescom passes over and through us, I work on. Kenoma now includes a "color contrast" mode for those who might find the default pallet a strain on their eyes, or for those who like red and blue more than black and white.

1 note

·

View note

Text

I've neglected this account for a while. My apologies, I am not very active on social media in general. Progress continues.

0 notes

Text

it's been a hell of a year and change, but I'm glad to announce that kenoma now has a steam page! go ahead and wishlist it now - or play the updated and slightly-expanded free demo and then wishlist it!

I hope you enjoy the demo, and look forward to the full release!

#indie#indie games#steam games#it's been 10000 years but its finally here#i had to pay 100 dollars to do this#that's business for you

1 note

·

View note

Text

is it a poor decision to revise concepts before the whole is finished? Maybe. But you can now move the bones around yourself.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

There are many ways to die in this place. Best not push your luck.

I wanted this post to be a video but it invariably compresses to unwatchability. We must content ourselves with a screenshot.

1 note

·

View note

Text

interactive moss mechanics

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Prolonged silence gives way: things continue to progress. Slowly, but it will be done.

Additionally, a greeting to all. I'm new here. See the project this is from (in DEMO form) here: https://brukholevin.itch.io/kenomademo

2 notes

·

View notes