Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

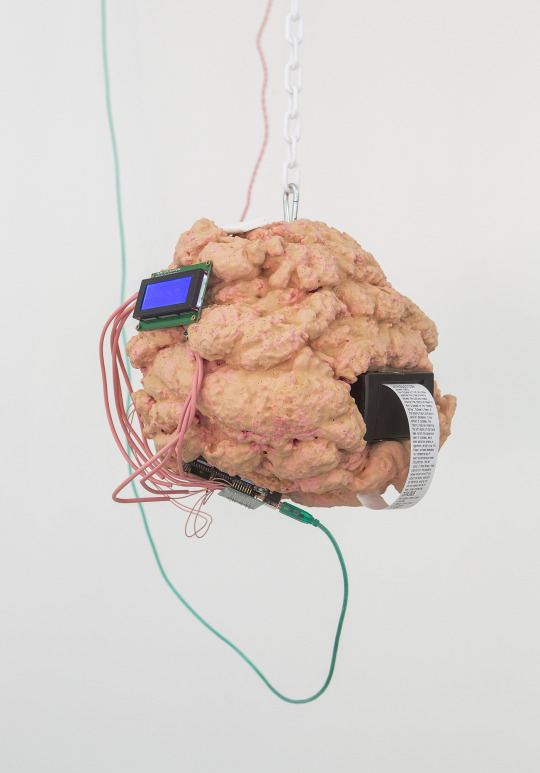

Uncanny Dimple

My final project Uncanny Dimple is a body of work that examines the close proximity between the cute and the creepy. Drawing from roboticist Masahiro Mori’s concept of the Uncanny Valley, which explains the eeriness of lifelike robots, my theory of the Uncanny Dimple portrays a parallel phenomenon in the context of cuteness. The robotic creatures inhabiting the dimple demonstrate the often contradictory affects we experience towards non-human actors. When does cuteness start to border on the grotesque? If cuteness is the outcome of extreme objectification of living beings, can it also be the result of an anthropomorphising inanimate objects? Why does cuteness trigger the impulse to nurture and to protect, but also to abuse and to violate? Cute things are often seen as innocent, passive, and submissive, but can they also manipulate, misbehave and demand attention?

This body of work is based on my MFA thesis Uncanny Dimple — Mapping the Cute and the Uncanny in Human-Robot Interaction, where I examine the aforementioned contradictions of cuteness by applying Donna Haraway’s Cyborg Manifesto (1991) and the Uncanny Valley theory by Masahiro Mori (1970). I also reference the recent research on the cognitive phenomenon of cute aggression, a commonly experiences impulse to harm cute objects. (Aragón et al. 2015; Stavropoulos & Alba 2018)

Sigmund Freud first coined the term uncanny in his 1919 essay Das Unheimliche to describe an unsettling proximity to familiarity encountered in dolls and wax figures. However, the contemporary use of the word has been inflated by the concept of the Uncanny Valley by roboticist Masahiro Mori. Mori’s notion was that lifelike but not quite living beings, such as anthropomorphic robots, trigger a strong sense of uneasiness in the viewer. When plotting experienced familiarity against human likeness, the curve dips into a steep recess — the so called Uncanny Valley — just before reaching true human resemblance.

As a rejection of rigid boundaries between “human”, “animal” and “machine”, Haraway’s cyborg theory touches many of the same points as Mori’s Uncanny Valley. Haraway addresses multiple persistent dichotomies which function as systems of domination against the “other” while mirroring the “self”, much like cuteness and uncanniness: “Chief among these troubling dualisms are self/other, mind/body, culture/nature, male/female, civilized/primitive, reality/appearance, whole/part, agent/resource, maker/made, active/passive, right/wrong, truth/illusion, total/partial, God/man.” (Haraway 1991: 59)

Haraway’s image of the cyborg, despite functioning more as a charged metaphor than an actual comment on the technology, still aptly demonstrates the dualistic nature of cuteness and its entanglements with the uncanny at the site of human-robot interaction. Furthermore, Haraway’s cyborg theory grounds the analysis of the cute to a wider socio-political context of feminist studies. In the Companion Species Manifesto where she updates her cyborg theory, Haraway (2003: 7) is adamantly reluctant to address cuteness as a potential source of emancipation (which seems to be the case with other feminists of the same generation): "None of this work is about finding sweet and nice — 'feminine' — worlds and knowledges free of the ravages and productivities of power. Rather, feminist inquiry is about understanding how things work, who is in the action, what might he possible, and how worldly actors might somehow be accountable to and love each other less violently." I argue on the contrary that some of these inquiries can be answered by exposing the potential of cuteness as a social and moral activator. While Haraway describes a false dichotomy between these “sweet and nice” worlds and “the ravages and productivities of power”, I believe that their entanglement is in fact an important site for feminist inquiry. By revealing the plump underbelly of cuteness, we can harness the subversive power it wields.

In my thesis I conclude that cuteness and uncanniness are both defined by their distance to what we consider “human” or “natural”, and shaped by the distribution of power in our relationships with objects that we deem having a mind or agency. I continue to propose that a similar phenomenon to the Uncanny Valley can be described in regard of cuteness, which I call the Uncanny Dimple. Much like Mori’s valley and Haraway’s cyborg, Uncanny Dimple is presented as a figuration: It does not necessarily try to make any empirical or quantitative claims about the experience of cuteness, but strives to utilise the diagram as a rhetorical device for better understanding the entangled affects of cuteness and uncanniness.

Similar to Mori’s visualisation of the Uncanny Valley, the Uncanny Dimple is mapped in a diagram where the horizontal axis denotes “human likeness”, but Mori’s vertical axis of “familiarity” is in this case replaced with cuteness. Similar to Mori, I propose that cuteness first increases proportionally with anthropomorphic features. As established in Konrad Lorenz’s Baby Schema model from 1943, cuteness also increase proportionally in the presence of neotenic (i.e. “babylike”) features, such as large eyes, tall forehead, chubby cheeks and small nose. I suggest that this applies only to some extent: When the neotenic features have reached a point where they are over-exaggerated beyond realism, but the total human likeness is still below the Threshold of Realism, cuteness climaxes at what I call the Cute Aggression Peak. When human likeness exceeds that point, cute aggression becomes unbearable, the experienced cuteness is surpassed by uncanniness, and the curve dips to the Uncanny Dimple.

I wanted to create various cute but uncanny creatures which all had their distinctive way of moving or interacting with the audience. I created multiple different prototypes of most of the creatures, and in the final installation I had eight different types:

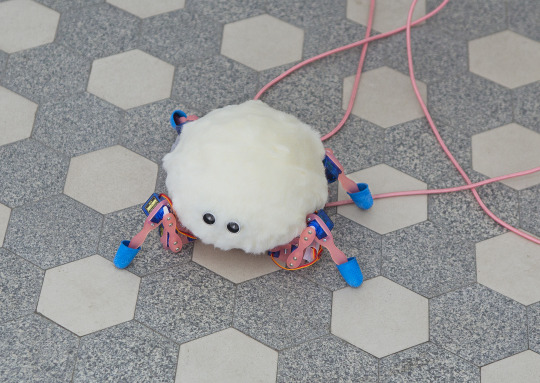

1. Sebastian is an interactive quadruped robot that can detect obstacles. Sebastian will wake up if it's approaced, and run away. The inverse kinematic functions for the quadruped gait are based on SunFounder's remote controlled robot. In the basic quadruped gait three legs are on the ground while one leg is moving. The algorithm calculates the angles for every joint in every leg at every given time, so that the centre of gravity of the robot stays inside the triangle of the three supporting legs. I designed all the parts and implemented the new dimensions in the code. I also added the ultrasonic sensor triggering and obstacle detection. For calculating distance measurements based on the ultrasonic sensor readings I used the New Ping library by Tim Eckel.

2. Ritu is an interactive robotic installation using Arduino, various sensors, servo motors and electromagnet. Users are prompted to feed the vertically suspended robot, which will descend, pick the treat from the bowl, and take it up to its nest. There is a hidden light sensor in the bowl, which senses if food is placed in the bowl. This will trigger the robot to descend using a continous rotation servo motor winch. The distance the robot moves vertically is based on the reading of a ultrasonic sensor. The robot uses an electromagnet attached to a moving arm to pick up objects from the bowl. After succesfully grabbing the object, the robot will ascend and drop the object in a suspended nest. For calculating distance measurements based on the ultrasonic sensor readings I used the New Ping library by Tim Eckel.

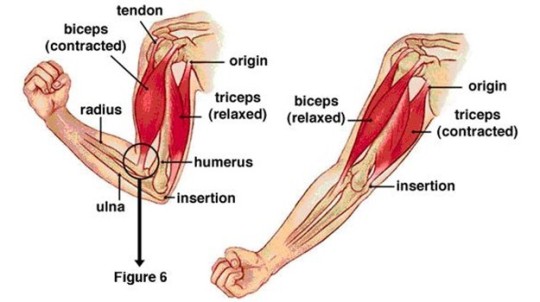

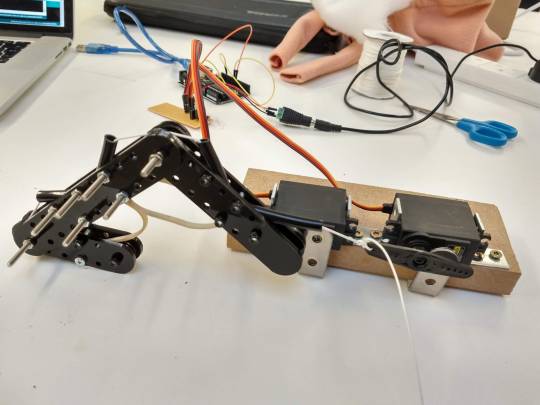

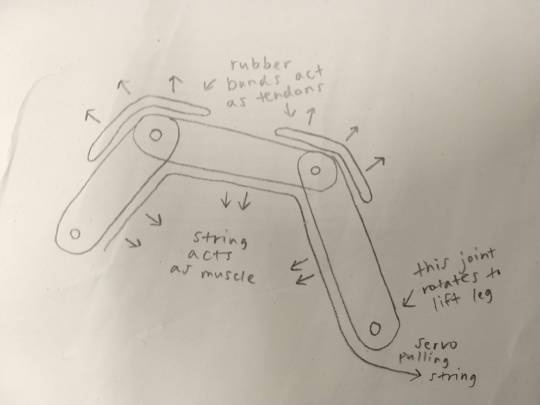

3. Crawler Bois are two monopod robots that move with motorised crawling legs that mimic the mechanism of real muscles and tendons. Each robot has a leg that consist of two joints, two servo motors, a string, and two rubber bands. The first servo lifts and lowers the leg, and the second servo tightens the string (the "muscle") which contracts the joins. When the string relaxes, the rubber bands (the "tendons") pull the joints to their original position. The robots move back and forth in a randomised sequence and sometimes do a small dance.

4. Lickers are three individually interactive robots using servo motors, Scotch Yoke mechanisms, and sound sensors. The Scotch Yoke is a reciprocating motion mechanism, in this case converting the rotational motion of a 360 degree servo motor into the linear motion of a licking silicone tongue protruding from the mouth of a creature. If a loud sound is detected, the creature will stop licking and lift up its ears. The treshold of the sound detection can be modified directly from a potentiometer on the sound sensor module.

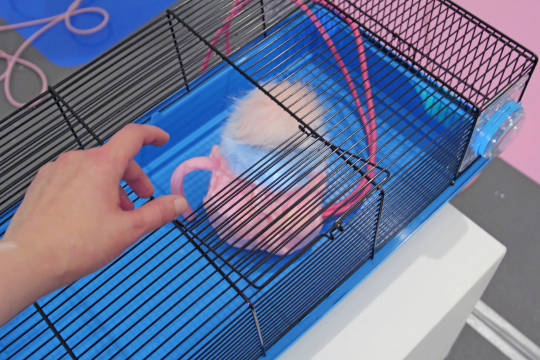

5. Shaking Little Critter is a simple interactive installation using an Arduino, a vibrating motor and a light sensor. Users are prompted to remove the creature's hat, after which it will "get cold" and start shaking around in its cage. The absence of the hat is detected with a light sensor on top of the creature's head.

6. Rat Queen is a robotic installation exploring the emergent features arising from the combination of pseudo-randomness and mechanic inaccuracy. It consist of five identical rats-like robots that are connected to a shared power supply with their tails. All the members of the Rat Queen move independently in randomised sequences, but because they are started at the same time, the randomness is identical, since the random seed is calculated based on the starting time of the program. However, due to small inaccuracies and differences in the continuous rotation servo motors and their installation, the movement patterns diverge, and the rats slowly get increasingly tangled with their tails.

7. Cute Aggression is an interactive sound installation using Arduino and Max MSP. Users can record sounds by whispering in a hidden microphone in the plush toy creature's ear. A tilt switch in the ear starts the recording when the ear is lifted. The sounds are played back when the user pets the creature. The petting is detected with conductive fabric using Capacitive sensing library by Paul Badger. The reading from the sensor is sent to a Max MSP patch via serial communication. The sounds a generated from the Arduino data using a granular synthesis method based on Nobuyasu Sakonda’s SugarSynth. Sounds can be modulated by manipulating the creature's nipples, which are silicone-covered potentiometers.

8. Cucumber Weasel is a modified version of the motorised toy know as weasel ball. The plastic ball has a weighted, rotating motor inside, which makes the ball roll and change directions. The toy usually has a furry “weasel” attached to it, but here it is replaced with a silicone cast of a cucumber.

References:

Aragón, O. R; Clark, M. S.; Dyer, R. L. & Bargh, J. A. (2015). “Dimorphous Expressions of Positive Emotion: Displays of Both Care and Aggression in Response to Cute Stimuli”. Psychological Science 26(3) pp. 259–273.

Badger, P. (2008). Capacitive sensing library.

Eckel, T. (2017). New Ping library for ultrasonic sensor.

Freud, S. (1919). The ‘Uncanny’. The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Volume XVII (1917-1919): An Infantile Neurosis and Other Works, pp. 217-256.

Haraway, D. (1991). "A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century," in Simians, Cyborgs and Women: The Reinvention of Nature. New York, NY: Routledge.

Haraway, D. (2003). The Companion Species Manifesto: Dogs, People, and Significant Otherness. Chicago, IL: Prickly Paradigm Press.

Lorenz, K. (1943). “Die angeborenen Formen moeglicher Erfahrung”. Z Tierpsychol., 5, pp. 235–409.

Mori, M. (2012). "The Uncanny Valley". IEEE Robotics & Automation Magazine, 19(2), pp. 98–100.

Rutanen, E. (2019). Uncanny Dimple — Mapping the Cute and the Uncanny in Human-Robot Interaction.

Sakonda, N. (2011). SugarSynth.

Sunfounder (n.d.). Crawling Quadruped Robot Kit v2.0.

Stavropoulos K. M. & Alba L. A. (2018). “‘It’s so Cute I Could Crush It!’: Understanding Neural Mechanisms of Cute Aggression”. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 12, pp. 300

1 note

·

View note

Text

Final Exhibition Progress

The project grew quite organically in the span of eight months since I didn’t have a clear idea how many or what kind of robots I wanted to create when I started. I quite enjoyed working in a way that allowed me to quickly jump from one prototype to another, constantly coming up with new ideas for interesting mechanisms or interactions. However this meant that some of the creatures were not developed as far as I would have wanted, since I more or less ended up choosing quantity over quality in some cases. Especially the interactive sound plushie, which was one of the first creatures I started developing, didn’t quite evolve past the first prototype phase because I constantly got carried away with new ideas. In the future I would definitely want to develop it further, probably in the form of a sound performance as I originally intended.

On the other hand, having multiple individual robots meant that there wasn’t going to be a single point of failure that would impair the entire installation. When one robot was malfunctioning (which they obviously did) I could simply take it aside without much effect to the overall experience. Nevertheless, one major area of improvement would be to make the robots more robust, so that they could actually run for multiple days without needing any parts replaced. Most breakdowns however were mainly due to using servo motors with plastic gears, since they were less expensive and more readily available.

Also having so many different features in one project forced me to streamline the technologies to the minimum, which ended up working to my benefit: I was pleasantly surprised how very simple means — just couple of servo motors and sensors — I needed to create as varied and engaging interactions. For example, I planned using a complex computer vision system for detecting the food placed in the bowl below Ritu, but ended up developing a much more simple, elegant and failsafe solution by placing a hidden light sensor in the bowl.

From the perspective of my theoretical research, I felt that my work was able to communicate my thesis of the Uncanny Dimple to the audience. In addition, I’m satisfied how approachable the work was for everyone: It was great to see how adults, small children and dogs alike were interested in interacting with the creatures.

I also enjoyed creating work within my own aesthetic and affective category of the Uncanny Dimple, since it allowed me to take on various different diversions and new skills, such as more complex robotics and Max MSP, but it was also constrictive enough to create a unified body of work. I still have plenty of unused ideas and sketches left for robots I didn’t have time to execute, which proves that this body of work is something I definitely would want to expand in the future.

0 notes

Text

Solo show: Uncanny Dimple

I had my first solo show Uncanny Dimple at Kosminen gallery in Helsinki from 25 July to 4 August. It was a good opportunity to show my final project before September’s degree show, and to see what works in an exhibition setting and what doesn’t. Overall I think the show was a great success: The opening was buzzing, and the feedback I got was overwhelmingly positive. I even got some coverage on national news.

Even though the contemporary art scene in Helsinki is quite vibrant, I still feel that computational arts is a relatively unknown field. It was great to see how much interest there was for robotic artworks, and how many passers-by did a double take and decided to visit the gallery.

I also printed my MFA thesis as a small zine which I sold at the exhibition. To my surprise, I sold all the 50 copies I had.

0 notes

Text

Developing a Crawl

While creating the animatronic “leg” for the creepy fetus-creature in the GRASPER installation, I became interested in different ways of locomotion this type of appendage would allow. I wanted to mimic the functionality of the muscular foot that clams and molluscs use for movement, so I started to research various types of robotic joints and artificial muscles.

youtube

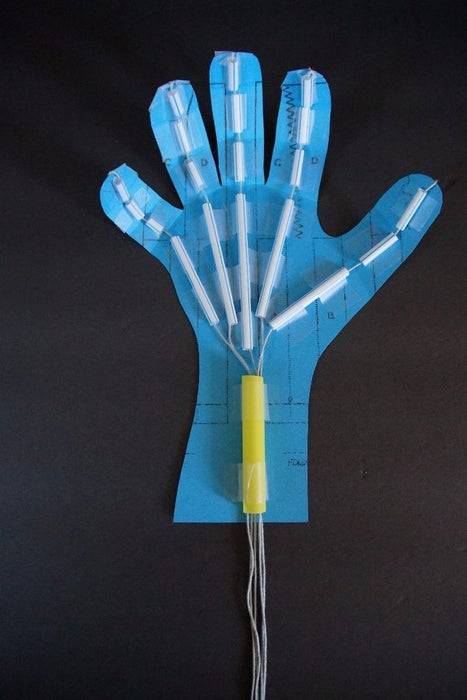

I developed a mechanism that was inspired by various simple robot hand tutorials available online, which imitates (in a very rudimentary way) the mechanism of biological muscles and tendons.

The mechanism consists of two servo motors, one which lifts the leg, and other that tightens the cord which flexes the joints. When the cord is released, the rubber bands on the opposite side will contract the leg to its original state.

Plenty of fine-tuning was required to accomplish an actual forward motion where the leg can pull the weight of the entire mechanism: The tightness of the cord and the rubber bands, the angle of the joints and the timing of contraction and elevation all affected the movement in complex ways. I also had to add a styrofoam ball coated with latex to the tip of the foot to help with traction.

View this post on Instagram

A post shared by Eevi Rutanen (@eebiru) on Mar 21, 2019 at 7:48am PDT

0 notes

Text

Revisiting GRASPER

In February I was invited to participate in the Binary Code group exhibition at the newly established Seager gallery in Deptford. It was a great experience to show again my installation GRASPER from last year’s MA degree show, and revisit some of the aspects of the installation that didn’t work that well the first time around. I decided to leave out the motorised knitting machine, since it was prone to malfunctioning and getting stuck, and replace it with a video of myself knitting. Similarly to the earlier version, the video was played back when visitors milked the silicone udder, and in that sense translating the manual labour and tactile knowledge of milking to the analogous labour and knowledge of knitting. I also liked the way the video added a new temporal aspect to the work, since the performance of the video was indexical to actual manual labour carried out in the past, but virtually re-enacted by the milker.

I also added another new feature to the installation: A strange, fetus-like tentacled creature, connected to the udder with an umbilical cord. I wanted to somehow display the aspect of care-taking, nurturing and mothering, which are vital to the themes of gendered knowledge and labour. The strained, uncanny movement of the jointed tentacle-leg is triggered with the udder, effectively giving the impression of feeding the creature with the act of milking.

0 notes

Text

Moodboard for 2019

In January I made this moodbard mapping some of my inspirations for the new year. Looking back to it now, I’m glad to notice that my current research project on the relationship of cuteness and uncanniness and and the accompanying artistic work with cute-creepy-creatures neatly encompasses many of the themes in the map.

0 notes

Text

Microlabour

Because of the painstaking window display project I didn’t have a lot of time to develop my MFA project during the first term. I had some vague ideas of the areas I wanted to explore, including speculative technologies, worldbuilding, and futurology. I wanted to have some kind of a rough prototype and/or proposal for the Work in Progress show in December, so I very quickly developed a small project around the future of labour. In the end I didn’t take this idea any further, but it was a fun exercise to very quickly prototype some tongue-in-cheek technologies for a speculative future.

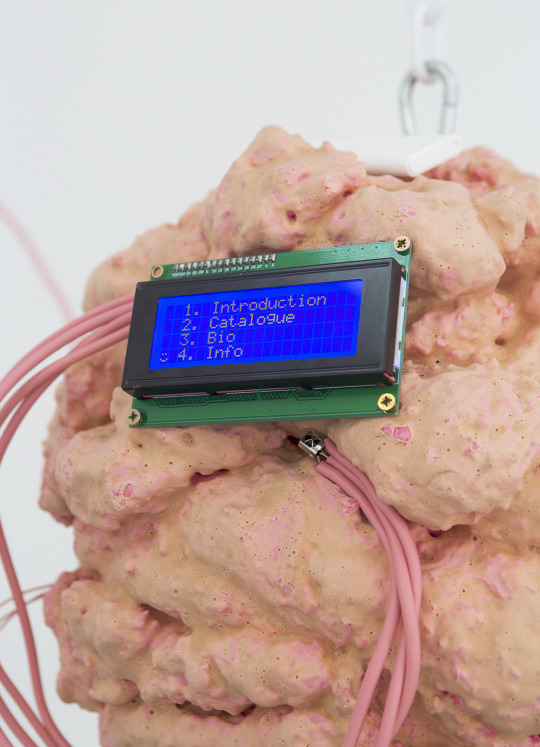

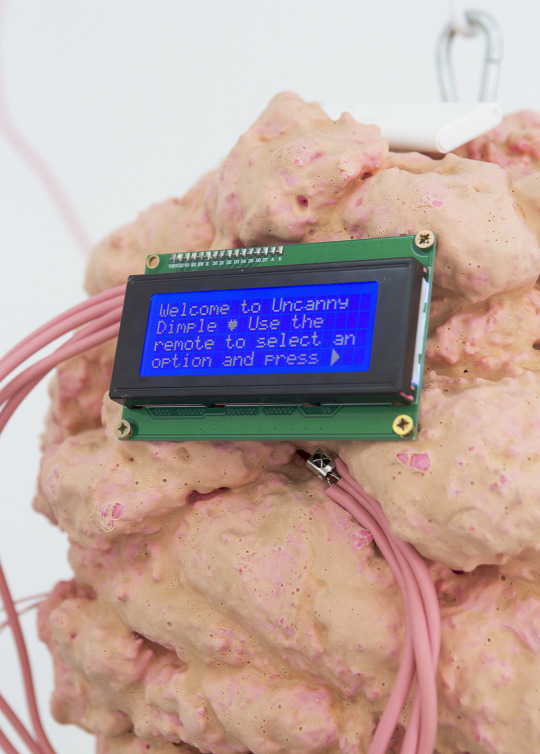

The project consisted of a short manual displayed on a e-reader which explained the context of the fictional future, and three prototypes of different technologies.

It’s the year 2119.

Due to advancements in robotics and artificial intelligence in the first half of the 21st century, most jobs have been automatised, and no longer require human labour. Universal basic income was globally introduced to provide an adequate level of welfare, and most labour now consists of human-intelligence microtasks carried out in the digital gift economy.

This microlabour entails jobs that humans still perform better than machines, such as specialised knowledge work, creative production and social relations. Voluntary online tasks, for instance creating blog content, writing reviews, moderating threads, coding snippets and updating databanks are exchanged with other microtasks in the digital marketplace. Human intelligence is also needed to train and manage the ubiquitous AIs and machine learning algorithms, with tasks such as creating datasets, testing for bias, and verifying results.

Because of the granular nature of microlabour, the total number of working hours is only 5-20 per week, but various short-lived microtasks are carried out constantly at all times. There is no separation between work and leisure, since microlabour is seen as a self-fulfilling hobby, or at least a mundane pastime. Most microtasks are inherently digital and carried out online, so there is no need for an office or a workspace. However, communal houses are small and overcrowded, so microlabour is usually performed on the move, and microlabour devices, the so called “taskers”, are made small and wearable.

Furthermore, rampant global warming has spiralled the world into a wide-spread energy crisis and a shortage of raw materials. Due to the depletion of mineral resources (Peak Gold, the exhumation of the last gold reserve on the planet, was reached in 2033), all electronics production is highly regulated and its raw materials thoroughly recycled. The exhaustion of the mineral indium in 2021 has made LCD screens unsustainably expensive. Therefore, the often crude and small-screened taskers are primarily intended for carrying out a single specific type of micro task.

In the widely adopted market socialist system, publicly owned corporations and co-operatives partake in the microlabour economy among individuals and small enterprises, exchanging tasks with goods, services or micropayments. Historical cryptocurrencies are still in moderate use, but cryptomining with non-renewable energy has been made illegal. Due to draughts and pollution induced by climate change, solar or water powered energy is hard to attain. So called “cryptofishing” — mining cryptocurrency with manually generated energy — has emerged as a popular pastime.

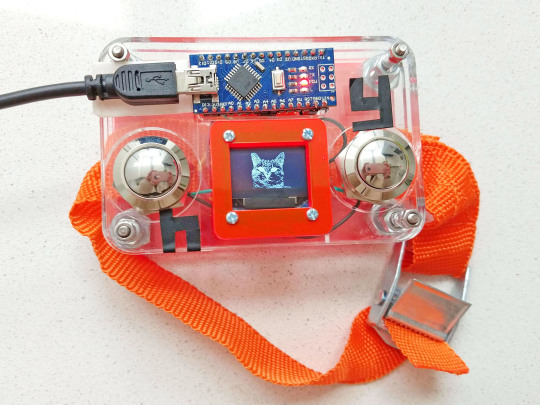

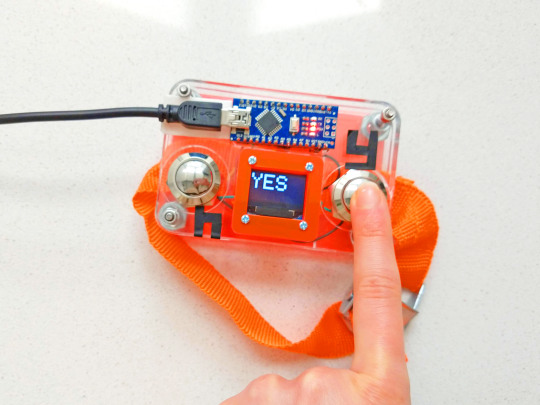

Tech 2/3: Image Dataset Microtasker

Despite the ubiquity of AIs and machine learning, human intelligence is still required to train and manage various algorithms. A typical low-level micro task entails annotating and categorising images for training sets. This type of microlabour is usually performed during idle moments while waiting for transport or sitting on the toilet. Suits also young children!

Tech 3/3: CryptoCrank

Due to the global environmental crisis, mining cryptocurrencies with non-renewable energy has been made illegal. So called “cryptofishing” — mining cryptocurrency with manually generated energy — has emerged as a popular pastime. This tedious but meditative hobby seldom yields considerable material results, much like its historical predecessor.

0 notes

Text

Scaling Up

Earlier this year I got the chance to collaborate with the advertising agency Wieden+Kennedy in an interactive window display for their headquarters in East London. The brief was to design an eye-catching, temporary window installation with the theme of “independence”, and W+K selected four students from the MA course to pitch ideas. They selected my proposal titled 2bcn4wur (To Be Seen For Who You Are), consisting of a grid of animatronic eyeballs that follow the movements of the passers-by with the help of computer vision.

In hindsight I should have been more realistic with the scale of my proposal, especially since I was not compensated for the nearly two months I spent on the project. The commission turned out to be by far the most complex, exhausting and stressful project I have ever taken on, and neither me or W+K were completely satisfied with the end result. However, I think the experience taught me a couple of useful lessons in project management, computational art commissions, and the challenges of scaling up.

Tip 1: Do not propose a project that you possibly can not deliver in the appointed timeframe.

Tip 2: Make sure you have an unambiguous written contract stating exactly the terms of the agreement and the amount of compensation. Don’t spend your own money for the client unless you are sure you are getting it back.

Tip 3: Making 48 animatronic eyeballs does not take 48 times as long as making one animatronic eyeball, but much, much longer.

Tip 4: Back up your files. All. The. Time.

Tip 5: Don’t ruin your physical and/or mental health on a project you are not personally invested at all.

Tip 6: Ask for help and accept it when it’s offered.

Tip 7: Don’t work for multinational advertising companies.

0 notes

Text

Naming, World-building, and the Magic of Programming

Finally reading for the first time Ursula Le Guin’s young adult fantasy novel A Wizard of Earthsea (1968), I was intrigued by the magic of Le Guin’s fictional universe: Wizards hold power over objects and beings by knowing their “true name”, the hidden essence of the thing and all its attributes bound in a single word:

When you know the fourfoil in all its seasons root and leaf and flower, by sight and scent and seed, then you may learn its true name, knowing its being

Names have the power of building worlds — that’s why every proper fantasy book begins with a map, charting the names of the kingdoms, mountains and rivers of the fictional universe, making them tangible and vivid.

Map of the Middle Earth from the novel Lord of the Rings (J. R. R. Tolkien, 1954)

Inventing a name summons the entire story of the named, bestowing it with history, meaning and purpose. My favourite episode of the animated series Rick and Morty accounts in a great detail the creation of an imaginary thingamabob called plumbus:

First they take the dinglebop, and they smooth it out with a bunch of schleem. The schleem is then repurposed for later batches. They take the dinglebop and push it through the krumbo, where the fleeb is rubbed against it. It's important that the fleeb is rubbed, because the fleeb has all of the fleeb juice. Then a schlomi shows up, and rubs it, and spits on it. They cut the fleeb. There are several hizzards in the way. The blamphs rub against the trumbles, and the plubus and grumbo are shaved away. That leaves you with a regular old plumbus.

This act of bestowing a thing with a name and building worlds from virtual nothingness made me think of programming: What is programming, if not naming things and through their name evoking some invisible magic? After all, as Arthur C. Clarke famously stated:

Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.

youtube

How a plumbus is made from the Rick and Morty episode Interdimensional Cable 2: Tempting Fate (Adult Swim, 2015).

0 notes

Text

Research Essay Leftovers

I was really intrigued by the idea of a feminist craft science which Harding (1986) introduces through the writings of Rose, Hartsock and Smith. Also Wajcman (2010) reminds us how arbitrary was the cultural change of thinking about technology as something masculine:

It is salutary to be reminded that it was only with the formation of engineering as a white, male middle-class profession that ‘male machines rather than female fabrics’ became the markers of technology […] During the late nineteenth century, mechanical and civil engineering increasingly came to define what technology is, diminishing the significance of both artefacts and forms of knowledge associated with women.

Rose argues that the practices of women scientists are still characteristically "craft labor” (in contrast with the “industrial” male-dominated labs). Female scientific inquiry gives emphasis to manual, mental, and emotional (Smith’s “hand, brain, and heart") activity characteristic of women's work more generally. She continues to state how the separation of manual from mental labor in capitalist production resulted in the mystifying abstractions of bourgeois science.

Smith proposes that the labour performed by women “relieves men of the need to take care of their bodies or of the local places where they exist, freeing them to immerse themselves in the world of abstract concepts.”, which consequently enhances the dichotomy that links men to abstract thinking, objectivity and universality, and women to craft practice, subjectivity and particularity.

Hartsock describes how the sensuous, concrete and relational aspects of the female experience grant women an empirical advantage over men:

the activity of a woman in the home as well as the work she does for wages keeps her continually in·contact with a world of qualities and change. Her immersion in the world of use-in concrete, many-qualitied, changing material processes-is more complete than [a man's]. And if life itself consists of sensuous activity, the vantage point available to women on the basis of the contribution to subsistence represents an intensification and deepening of the materialist world view and consciousness available to the producers of commodities in capitalism, an intensification of class consciousness

Rose argues that a craft-organised area of inquiry would make possible ”a more complete materialism, a truer knowledge."

I did not have the time or space to explore the possibilities of a craft-based, sensuous epistemology in my essay, but would like to research this area in the future. This could possibly be linked to some of the discourses in fine arts and cultural studies about the “wisdom of the hand”.

References

Harding, S. (1986) The Science Question in Feminism. New York: Cornell University Press.

Wajcman, J. (2010) Feminist theories of technology. Cambridge Journal of Economics [online], 34(1), pp. 143–152. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/ben057 [Accessed 28 March 2018]

0 notes

Video

tumblr

Teeny Tiny ATtiny85 Project Part II

Tiny balloon pump using ATtiny85. The printed circuit board was designed in Eagle and milled with a Roland CNC.

First schematic made in Fritzing.

Second schematic in Eagle.

PCB layout from Eagle.

First try. The traces were not completely isolated and the outline was out of focus.

Second try. The traces were too narrow.

Third try. It works!

Soldered PCB. The button from the original schematic was replaced with a potentiometer.

Finished project! The power cord was repurposed from an old iPhone charger and the case was made from laser-cut acrylic and a 3D printed nozzle.

0 notes

Video

tumblr

A teeny tiny ATtiny85 project

Prototype for a balloon timer using ATtiny85 chip, a pushbutton, a micro DC air pump, and a hacked USB iPhone charger as a 5V power source.

0 notes

Text

Skroderiders

Project Plan for Physical Computing Term 2

In my Physical Computing project I want to explore the agency of non-human actors and the possibilities of artificial mutualism. I was inspired by one of my all-time favourite science fiction novels, A Fire Upon the Deep by Vernor Vinge, where he introduces the alien species of skroderiders. Skroderiders are a plant-like, sentient race, which gained mobility when a superhuman, transcendent being gave them wheeled mechanical constructs (skrodes) to move around and to provide short-term memory.

I want to examine the implications of bestowing agency to a non-human being, especially in the case of a motionless species becoming mobile. In nature symbiosis between two species always requires immediate physical contact and proximity, but with the ability to move the prospects for new kinds of symbiosis become imminent. In my project I wish to portray a form of artificial mutualism, a beneficial relationship between two cybernetic beings.

In addition to the strictly biological aspects of mutualism, I want to explore the notion of a non-human, mutualistic relationship as a form of romance. Vinge’s novel succeeds in describing the relationship between two skroderider characters, Greenstalk and Blueshell, as a definitely alien but still relatable portrayal of a connection between two individuals. In my project I wish to illustrate a similar sense of an alien love story between two non-humanoid beings.

My physical computing project is going to consist of two autonomous, mobile plant cyborgs that can supply each other with essential resources. The plants can move around on wheeled platforms which are controlled with Arduinos. The platforms have rotating ultrasonic sensors for avoiding obstacle, and infrared LEDs and sensors for finding each other. Both IR LEDs send unique pulses that are received by the sensor on the other plant. The direction of the incoming pulse can be detected by narrowing the field of view of the receiver. When the plants find each other, one can supply the other with water, and the second supplies a growing light.

One-page Design

Electronics

2 x Arduino boards 2 x 2 DC motors and wheels 2 x 2 servo motors 2 x ultrasonic sensors 2 x IR LEDs 2 x IR sensors water pump growing light LED strip 2 x 6V power sources 2 x motor shields?

Other materials

2 x small house plants 2 x swivel castor wheels 2 x platforms (Laser cut from acrylic? Skirting from some other material?) water container, tubing arm/base thing for grow light strips

Things to consider

How to detect that the plants are touching each other, and to also detect the direction of the touch for supplying water/light to the right direction? Maybe attaching areas of conductive material to the sides of the platform, and detecting states of change with digitalRead when a circuit is closed on one of the areas? How to make sure that the plants don’t consider each other as obstacles to avoid? Does the narrowed field of view able the IR sensor to detect the direction of the IR pulse reliably? Should the IR receiver not be rotating with the ultrasonic sensor? Would a motor shield be the easiest way to control 2 DC motors and 2 servos?

Resources

Using IR Sensors and transmitters

Obstacle avoiding robot (without rotating ultrasonic)

Inspiration

Terranaut II (2006) by Seth Steiner: A Blood Parrot fish explores terra firma from within a robotic vehicle that tracks the fish's location within the vessel and steers the vehicle accordingly.

Indaplant project (2013) by Elizabeth Demaray: An Act Of Trans-Species Giving.

0 notes

Text

Term 2 Project Proposal

Computational Arts-based Research and Theory

What is the overarching area of research?

Dan McQuillan describes how predictions made by machine learning algorithms are becoming a self-fulfilling form of governance. Despite the fact that we can’t fully understand how deep learning neural networks work, we trust them to make decisions with material consequences of varying severity. This blind trust on the presumed objectivity of data science, the following “abstraction of accountability” (McQuillan), and the confusion between correlation and causation can lead to policies that are biased, totalising and extra-judicial but justified by law.

Biases and prejudices do not occur in machine learning algorithms spontaneously, but are infected via the data sets that are used in the training of said algorithms. In my research project I want to expose the discriminatory and biased nature of data sets used in machine learning, focusing on ImageNet and WordNet databases, which are among the largest and most used open data sources for deep learning.

In my research project I wish to suggest countermeasures against the algorithmic pre-empting of the future and the biased knowledge claims of prevailing data science methods. Drawing from feminist perspectives on science and speculative research methodologies, I wish to propose alternative epistemologies that are more situated, embodied, participatory, pluralistic and nomadic than the hegemonic knowledge production.

I will visualise these expositions and inquiries in the form of an interactive web application that invites people to a participatory creation of alternative machine learning data sets.

What are the key questions or queries you will address?

How do biased data sets affect the knowledge production of contemporary machine learning algorithms? What is situated knowledge like and how can it be produced? How to produce knowledge outside the hegemonic epistemology?

Why are you motivated to undertake this project?

In my opinion, a computational dystopia is not about a totalitarian regime of hostile AIs, but a discriminatory algorithmic governance infected by human bias and prejudice. Signs of such governance are already detectable, so I think there is an urgent need for countermeasures and alternative approaches.

What theoretical frameworks will you use in your work to guide you?

—Feminist technoscience, e.g. situated knowledge, standpoint theory, agential realism —Speculative realism, speculative research methodology

Image: Imagenet database

Related papers & articles

—Dan McQuillan: Algorithmic states of exception —Dan McQuillan: Data Science as Machinic Neoplatonism —Donna Haraway: Situated knowledges: The science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspectives. In Simians, cyborgs and women. —Karen Barad: Getting Real: Technoscientific Practices and the Materialization of Reality. —Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Feminist Perspectives on Science. —Alex Wilkie, Martin Savransky, Marsha Rosengarten: Speculative Research: The Lure of Possible Futures —Steven Shaviro: The Universe of Things: On Speculative Realism —Gilles Deleuze & Felix Guattari: Nomadology: The War Machine —ImageNet & WordNet databases

0 notes

Text

Ways of Machine Seeing

Class preparation for Week 5 / Computational Theory

Surveillance seems to be a reoccurring theme in artworks that utilise computer vision, probably partly because of the ubiquity of CCTV cameras and facial recognition algorithms in our daily lives, and partly because of the potent symbols of power, authority and control such technologies provide. In addition, computational processes for tracking and recognising human faces and bodies are highly advanced compared to other forms of computer vision, precisely because of their importance for substantially funded fields such as security and military.

Among the artists who explore the theme of surveillance is David Rokeby with his artwork Sorting Daemon from 2003. Concerned with the increase of automated profiling by authorities as part of the "war on terrorism", Rokeby created an computational installation that records passers-by and sorts the components of their image based on colour. (Rokeby, 2010)

vimeo

An other, even more sinister example of computational art and surveillance is the Suicide Box by the Bureau of Inverse Technology (Natalie Jeremijenko and Kate Rich). The artwork consisted of a motion detection video system installed in the vicinity of the Golden Gate Bridge for 100 days in 1996. The system was designed to detect and record vertical movement, thus documenting 17 suicides committed on the bridge during the time period. (Bureau of Inverse Technology, 1996.) BIT observed that the local authorities had simultaneously reported only 13 suicides, emphasising the artists’ idea to “track a tragic social phenomenon which was not being counted — that is, doesn't count” (as cited in Levin, 2006).

Although inspired by surveillance systems, Rokeby’s piece adopts a different way of machine seeing than government-deployed algorithms: In stead of using computer vision for racial profiling, Sorting Daemon sees skin colour as an arbitrary attribute in the same category as the colour of clothing. Faces and bodies are arbitrarily but systematically scanned, disassembled and categorised. In epistemological sense, the former way of machine seeing is harmful because the knowledge it produces is tainted by hegemonic bias (Cox, 2016), but the latter might be just as violent. As Cox describes, seeing machines have no interest in content or context. The faces and bodies for the algorithm in Sorting Daemon are not people, but pixels. Knowledge that is based on purely visual systems of power is often ambiguous (Cox, 2016) and unaccounted for.

This “abstraction of accountability” (McQuillan, 2017) is partly what makes the way of machine seeing in the case of Suicide Box so unnerving. The artwork witnesses and documents deaths, but does not, and in fact can not, intervene or prevent them. As Fei-Fei Li (2015) grimly points out in her TED talk, security cameras are everywhere, but they still can’t alert us when a child is drowning in a swimming pool. Suicide Box makes visible this shortcoming of machine vision: Seeing may produce knowledge, but knowledge does not necessarily produce action.

When viewed through black intersectional analysis as described by Safiya Umoja Noble (2006), the ambiguity of Sorting Daemon reads as an inadequate attempt to address racial inequality. The artwork seems to marginalise oppression and prejudice and focus on the representation and formation of race, in stead of exposing the direct material consequences for the oppressed as Noble encourages.

Suicide Box can be seen as an example of a more forensic approach for examining social issues, since it was designed to provide public data of a social phenomenon not previously accurately quantified. Located close to Silicon Valley, which is both the information capital and the suicide capital of the USA (BIT, 1996), the artwork draws attention to the private struggles taking place on the underside of the opulent technology industry. Black intersectional analysis of the artwork’s premises exposes also the race-related precarity in the industry: According to the studies of David Pellow and Lisa Sun-Hee Park (2002), the perceivable wealth and capital accumulation of Silicone Valley has been achieved by the exploitation of the invisible labour force of immigrants and other marginalised and racialised minorities.

References

Bureau of Inverse Technology (1996) SUiCIDE BOX [SBX]_. Bureau of Inverse Technology website.

Cox, G. (2016) “Ways of Machine Seeing”. Unthinking photography.

Levin, G. (2006) ”Computer Vision for Artists and Designers: Pedagogic Tools and Techniques for Novice Programmers". Journal of Artificial Intelligence and Society, Vol. 20.4. Springer Verlag, 2006.

Li, F. (2015) “How we're teaching computers to understand pictures”. TED2015.

McQuillan, D. (2017) “Data Science as Machinic Neoplatonism”. Philosophy & Technology pp 1–20, 2017.

Noble, S. U. (2006) “A Future for Intersectional Black Feminist Technology Studies”. S&F Online, Vol. 13.3-14.1, 2016.

Pellow, D. N. & Park, L. S. (2002) The Silicon Valley of Dreams: Environmental Injustice, Immigrant Workers, and the High-Tech Global Economy. New York: New York University Press.

Rokeby, David (2003) Sorting Daemon. David Rokeby’s website

0 notes

Text

Hacklab: iCod — the Smart Codpiece

Physical Computig T2 W3

For my Hacklab prototype I wanted to create a piece of wearable technology that examines the late capitalistic craze for self-quantification and optimised performance, characteristic to contemporary wearables. My concept for iCod, a smart codpiece, satirises the commercialisation and computerisation of reproductive healthcare and fertility products, which are usually aimed at women.

More documentation coming soon!

0 notes

Video

tumblr

Physical Computing T2 W2: Fabric buttons

Fabric buttons with conductive fabric, conductive snap fasteners and tilt switch. When the larger button is pressed, the two conductive fabric strips inside it come into contact with each other and close the circuit. This input turns on the LED in the smaller button. When the larger button is tilted, the tilt switch signals the vibrating motor inside the button to turn on and the piezo buzzer to make a sound. When the two buttons are connected with the snap fastener a circuit is completed and the LED in the smaller button is lit.

0 notes