Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

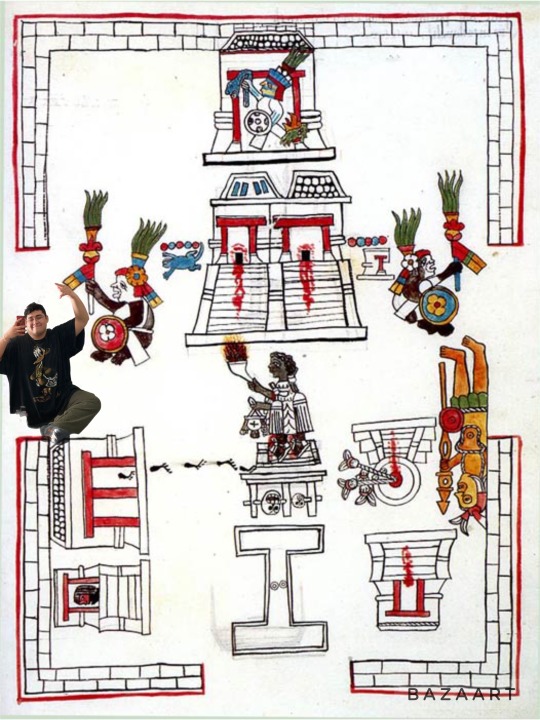

Pictured: me at the meeting of the Aztecs and Spaniards

Day 5: The meeting between the Aztecs and the Spaniards

On the last day of my trip I was extremely fortunate to experience the first encounter between the Spaniards and the Aztec. While I was strolling through the Tenochtitlan, word spread like wildfire about an incident that occurred at Montezuma’s palace. You could feel the tension in the air and the feeling of uncertainty weighed heavy on the Aztec people. Apparently a common man from the Aztec city of Mictlancuauhtla appeared before the emperor unannounced and informed him that when he was along the coast, he saw what appeared to be a moving mountain range floating in the water. Montezuma then sent out one of his priests and an ambassador to the city of Cuetlaxtlan to inform whoever was in charge about this incident. I was able to spot this convoy heading out of the city and quickly followed them. I was beyond thrilled as I was going to experience what I considered the defining moment in Mesoamerican history. Once I had arrived at the coast I was pleased to see that I came right on time. The convoy Montezuma had sent out had just climbed into a canoe and had brought valuable goods such as capes that were in Montezuma’s possession as if they were going to trade. At first I didn’t understand why they did this as they weren’t merchants, they were valuable members of the emperor’s court, but I was informed afterwards by the group that they took on the guise of traders so they could act as spies and gather information to relay back without arousing suspicion, something I had learned about a couple days ago. Once the group had reached the Spaniards, they performed a ceremony which I initially found odd as it wasn’t their custom to do a ceremony when they greeted someone. However once the group came back to shore, I overheard how they believed that it was their god Quetzalcoatl who was on these ships. Once they were on the boats, Montezuma’s convoy exchanged their goods. The Spanish weren't too impressed by the capes offered to them, but seemed a lot more interested once the Aztecs gave them these green and yellow necklaces. I believe that this moment in particular is what changed the course of history. The reason why the Spanish began exploring mainland America was because they were hoping to gain more valuable resources. So I believe that if they didn’t receive these necklaces, maybe they wouldn’t have continued inland. Therefore, if they didn’t continue inland perhaps the collapse of the Aztec empire wouldn’t have occurred the way it did. It’s just fascinating to think about what could have happened if this one event played out differently.

Bibliography

Bernardino de Sahagun, Fray. General History of the Things of New Spain: The Conquest of Mexico, vol. 12, Translated by Charles E. Dibble and Arthur J.O. Anderson, Sante Fe, The School of American Research, 1975.

Bentely, Jerry, and Ziegler, Herbert. Traditions and Encounters: A Global Perspective on the Past, vol. 2, Boston, McGraw-Hill, 2000.

León Portilla, Miguel. The Broken Spears: the Aztec Account of the Conquest of Mexico. Boston, Beacon Press, 2006. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/heb02772.0001.001

“Two worlds collide: Spanish conquistadors and Aztecs”, History Extra, Published August 5, 2021, accessed July 1, 2023

0 notes

Text

Pictured: Me with a figure of Chicome coatl

Day 4: Maize significance

During my stay at Tenochtitlan, I realized how important maize was to the Aztecs. One of the days the people were celebrating a religious feast in honor of the god Cinteotl who was the god of maize. While I was walking around the city I noticed a foul metallic smell that filled the air. I didn’t know what to make of it until I saw everyone sprinkling something at the foot of their doors. It wasn’t until I got closer that I realized they were using their own blood from their ears and calves to sprinkle on reeds they placed in front of their doors. I stopped a man who just finished this task and asked him what was going on. He was the one who informed me of the ceremony and he offered to show me the other preparations the people were doing. He took me to a maize field where people were taking small stalks of maize and placing them with flowers. I participated too, because everyone was doing it and I felt I would be left out if I didn't. Then we walked over to a house they called calpulli to place our bouquets of maize and flowers. Afterwards everyone proceeded to the pyramid of the goddess Chicome coatl, where we were greeted with reenactments of battle. The Aztecs seem to relate warfare with their religion very heavily just like how they associate warfare with their ball games. Afterwards I noticed how all the girls had ears of maize on their backs and that they were moving in procession inside the pyramid. I snuck a glance inside the pyramid from the outside, and noticed they were only presenting their stalks of maize to the images of the goddess inside the pyramid. Then they would take their stalks and bring them back home. I asked my guide, why they were doing this? He told me that Chicome coatl was the creator and giver of all that was necessary for life and that the maize the girls brought was blessed by her. He also mentioned how the girls would take the seed of these blessed maize and would plant them for next year's harvest. It makes sense why they would participate in this ritual as they believed by pleasing the gods associated with the crop, next year’s harvest would be bountiful. The choice to specifically make sure the maize gods were pleased was because of how the Aztecs depended on corn, in fact for decades prior past central Mexican populations depended on maize to survive. Maize was so integral to society that those who were unable to prepare and cultivate their own maize were seen as having low social status. Maize was so important that women who had skill in preparing maize into delicacies were often rewarded and respected by all of Aztec society. I would have never guessed that a simple crop would be so important if I had not experienced this ritual.

Bibliography:

Bernardino de Sahagun, Fray. General History of the Things of New Spain: The Ceremonies, vol. 2, Translated by Charles E. Dibble and Arthur J.O. Anderson, Sante Fe, The School of American Research, 1981

Biskowski, Martin. “MAIZE PREPARATION AND THE AZTEC SUBSISTENCE ECONOMY.” Ancient Mesoamerica 11, no. 2 (2000): 293–306. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26308239.

Maize Deity (Chicomecoatl), 15th-early 16th century, basalt, 35.6 × 18.1 × 8.9 cm, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, accessed July 1, 2023, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/307644

0 notes

Text

Pictured: Me at the center of Tenochtitlan with the ballcourt in front of the Twin Pyramids

Day 3: Mesoamerican Ball Game

I had the opportunity to experience another memorable event that I couldn't believe I had the chance to see. I was able to watch an actual match of the Mesoamerican ball game. The air was filled with the roar of the crowd, you could hardly hear yourself think. The game was played in stone carved ball courts which had two parallel structures on both sides to form an alley in the shape of a capital letter I. There were two teams of two men per team and they were hitting a rubber ball with their thigh or upper arm in order to get the ball through a stone ring on each wall of the alley. The players were wearing gear made up of leather, wood, and cloth over their thighs, arms, and hands. Before the game started I was looking at the crowd and noticed something interesting. It seemed like some spectators were betting with capes! It was funny to see that betting on sports had been around for centuries -- I guess some things are just ingrained in human nature. The ball court here at Tenochtitlan was truly beautiful. It was right in front of the great twin pyramid. I found it interesting that they put this ball game right in front of this sacred place, but ultimately it makes sense. The ball game in Mesoamerica was much more than just a recreational pastime; it was symbolic of the movement of the sun, moon, and planets. There was another interpretation of the ballgame, that it was a public reenactment of war. Sometimes during these ballgames the victors would sacrifice the losing team, just like warriors would take prisoners of war to be sacrificed. Thankfully this game wasn’t one of those matches... I don’t think I would’ve stayed in if that was the case. This game was an integral part of Aztec society as it was not just a popular pastime, but it served as a reminder of the importance of the heavenly bodies and the religious significance of war.

Bibliography

Berardino de Sahagun, Fray. Plan of the Great Temple Precinct at Tenochtitlan, Mexico. In “The Ballgame” by Mary Ellen Miller Record of the Art Museum, Princeton University, 48, no. 2 (1989) Figure. 3.

Cohodas, Marvin. “The Symbolism and Ritual Function of the Middle Classic Ball Game in Mesoamerica.” American Indian Quarterly 2, no. 2 (1975): 99–130. https://doi.org/10.2307/1183498.

Miller, Mary Ellen. “The Ballgame.” Record of the Art Museum, Princeton University 48, no. 2 (1989): 22–31. https://doi.org/10.2307/3774731.

0 notes

Text

Pictured: Me finding out there are different colored maize.

Day 2: Tenochtitlan Market

On the second day of my stay at Tenochtitlan I decided to head to the markets. As I was walking towards the markets the sound of voices, animals, and other noises grew ever so louder. Soon I was hit by a wall of various smells, it was such a mixture of different scents: the almost rancid musk of livestock and meats that were out in the hot sun, the freshness of crops that were just harvested, and the aroma of various different spices that tickled my nose so much I kept sneezing. There was an endless sea of merchants who set up along the market. It was quite intimidating but then I realized I wasn’t planning on buying anything so I shouldn't feel intimidated. The main reason I came to the market was to see first hand what people were selling as I had heard that the Aztecs had set up extensive trade routes that branched throughout most of Mesoamerica. Within Aztec society, merchants, colloquially known as Pocheta, were their own social class with their own hierarchy. From what I saw at the market, there are two types of merchants: minor merchants who sold their goods they made or cultivated at the local level, and extremely wealthy merchants who hired minor merchants to sell for them. At first I couldn’t tell which merchant was which unless I asked around. I was told that most Pocheta purposely hid their wealth because if they didn’t, the local nobles would get angry at them. As I continued to walk through the markets I was honestly surprised to see that each merchant specialized in one product. There were dedicated merchants for specific crops such as maize, tomatoes, cacao, and chilis. What especially surprised me is how one can see how vast Aztec trade routes were just by looking at the products sold. I stumbled upon a cacao merchant who was selling cacao seeds from Guatemala. These Pocheta who traveled throughout the Mesoamerican world would not only obtain different goods, but information as well. As a result many of them would be employed as spies for the empire gathering intel about rivals. These markets, like the one I visited in Tenochtitlan, really have provided me with a deeper understanding of Aztec society. The Aztecs were a very worldly people, they had influence throughout Mesoamerica because of these markets and merchants. They were able to be informed about foreign affairs because of Aztec merchants and had a large consumer culture as they had access to goods not found within their borders.

Bibliography

Bernardino de Sahagun, Fray. General History of the Things of New Spain: The People, vol. 10, Translated by Charles E. Dibble and Arthur J.O. Anderson, Sante Fe, The School of American Research, 1961.

Diorama of Tenochtitlan, American Museum of Natural History, accessed July 1, 2023, https://www.amnh.org/exhibitions/our-global-kitchen-food-nature-culture

Sherry, Bennet, “Long-Distance Trade in the Americas”, Khan Academy, Accessed June, 28, 2023, https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/whp-origins/era-4-regional/42-systems-restructure-betaa/a/long-distance-trade-in-the-americas-beta

0 notes

Text

Pictured: Selfie with Tenochtitlan

Day 1: Tenochtitlan

It is my first day here at Tenochtitlan and I can safely say this is one of the greatest cities that have ever existed. I made my way outside the city on top of a mountain surrounding the city to gain a better view and I cannot explain the sheer beauty of this city. The city is right in the middle of a massive lake. It looks as if it rose up from the water as there is no land touching any of the sides. The creation of this seemingly floating city was due to the ingenious engineering of the Aztecs. They created a system of floating islands, known as chinampas, that they anchored by planting trees. These islands made it easier for the city to grow since they provided fertile land for agriculture which allowed inhabitants to eventually create their own independent food supply. From the mountain top, I was able to view how organized the city was. In the middle of the city you can see a large white town square where the pyramids and religious temples were located. This town square was shining in the sunlight and it resembled a white pearl surrounded by the dark blue water of the lake surrounded by the city. The mountains and land around the city was a dark emerald green that encapsulated the lake. In the lake you could see the fishermen in the canoes. There were hundreds of them floating on top of the lake. I could see four roads that led out of the city that reminded me of a cardinal rose. On these roads I could see people walking in and out of the city probably with goods to trade but I couldn’t be sure because from afar they looked like black ants marching into an ant hill. The fact that this city existed in this remote part of the world is astounding. I even heard that Hernan Cortez compared its size to the Spanish city of Cordova.

Bibliography

Artist impression of Tenochtitlan at its height, Ancient Wisdom, accessed July 1, 2023. http://www.ancient-wisdom.com/mexicotenochtitlan.htm

Cortes, Hernando. Tenochtitlan. 1525 CE. https://jstor.org/stable/community.23779766.

Cortez, Hernan, “Cortez Describes Tenochtitlan”, American Historical Association. Accessed June 28, 2023, https://www.historians.org/teaching-and-learning/teaching-resources-for-historians/teaching-and-learning-in-the-digital-age/the-history-of-the-americas/the-conquest-of-mexico/letters-from-hernan-cortes/cortes-describes-tenochtitlan

James-Chakraborty, Kathleen. “Tenochtitlán and Cuzco.” In Architecture since 1400, 16–29. University of Minnesota Press, 2014. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/j.ctt9qh39w.6.

1 note

·

View note