Text

Response #8

Continuing with relational analysis of musical works, this response focuses on the work of formative sound and machine designers: Daphne Oram, Suzanne Ciani, Laurie Spiegel, and Laurie Anderson.

Daphne Oram Rotolock (1958) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tgpZi0ZnA5I

Daphne Oram (1925-2003) was a British electronic music composer and electronic instrument designer. Co-founder of the BBC radiophonic workshop, the UK's main electronic music center before their popularization in universities, she was an important figure of the country's experimental composition tradition, which is being rediscovered today. Her main technological project, a visual sound design machine called the Oramics machine, has been recently redevelopped and her book An Individual Note just republished.

It is unclear if this piece was played on the oramics device but as it was completed a year prior to the piece, it at least influenced Oram in the design of this work. The short composition, which timbrally plays off potentially familiar instruments (guitar, organ…) only does so in an ambiguous way. The ternary rhythm and ample delay / reverb match the microstructure of individual notes with the piece's somewhat accessible but uneasy overall mood.

Considering Born's four axes of relationality in music, it seems important to note that this uneasy yet accessible content is probably related to the role of the Radiophonic Workshop at the BBC. The BBC, an important government body of communication and public service, was also developing experiments such as this group of technicians and artists. However, the gender dynamics of that mid-size social group itself was uneasy: women, although present in the workshop, did not enjoy anything close to parity in the electronic music world of that time. Britain was no exception. Amidst a slow and uneven push towards inclusivity in artistic practices in institutions, questions of economic viability and commercial potential clearly shaped the experiments that were developed and shared. Rotolock, in a minute and thirty seconds, is before all else the work of Oram, a reflection of her ideals and ideas in terms of what technology could be used to do in a musical context. However, to the extent that this heavily loaded context could not be escaped any more in her time as it can be escaped today, this dual and uneven reading of this piece as a compromise between individual intent and social conditions remains.

https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/an-electronic-music-classic-reborn

2. Delia Derbyshire Pot-au-feu (1968) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jpdiMcEeTJA

Oram's colleague, Delia Derbyshire (1937-2001), also participated in the Radiophonic Workshop. Where Oram has regained fame for her development of the workshop and the Oramics machine, Derbyshire is known for the opening theme of the still-popular long running TV show Doctor Who.

In the case of Pot-au-Feu, a 1968 piece composed with a combination of tape editing and synthesis techniques, the eerie and uncomfortable higher pitches and opening rumbles ally the unease of Rotolock with a more rhythmic background that would eventually come to characterize modern electronic music.

Here again, the four orders of Born relational musicology are interconnected and relevant. The piece, as the product of Derbyshire's interaction with technicians and machines within the studio, displays the mastery of the composer at using new tools to compose a music aware of the tropes of her time, but also take into account the timbral and structural potential of the newly afforded machines. Those machines, mostly available because of the technological research and overproduction of the second world war, made it to Derbyshire through the innovative work of audio technology designers, but also of those at the BBC that wished to invest in diversifying their sources of music.

It appears as no coincidence that electronic experiments done at the BBC tend to be in these time formats reminiscent more of pop songs or jingles than of the massive monolithic compositions that build much of the contemporary avant garde canon. Considering the relatively recent re-appraisal of the legacy of people like Oram and Derbyshire, it seems relevant to remember some words from Pauline Oliveros, which tie together multiple orders of Born's relationalities (the microsocials of listening with the macrosocials of class, gender, race and wider economic concerns):

Critics do a great deal of damage by wishing to discover "greatness." It does not matter that not all composers are great composers; it matters that this activity be encouraged among all the population, that we communicate with each other in nondestructive ways. Women composers are very often dismissed as minor or light-weight talents on the basis of one work by critics who have never examined their scores or waited for later developments.

(Oliveros, 1970).

Oliveros, Pauline. "And Don't Call Them 'Lady 'Composers." New York Times 13 (1970).

BBC Radiophonic Workshop Unit Delta studio (1966)

3. Suzanne Ciani The fifth wave: Water Lullaby (1982) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wgJfXeGqNEY

Born 1946, Suzanne Ciani is notorious for her long career between advertisement sound and composition. The history of her work is often connected to Buchla synthesizers, which she used throughout that career and still performs with today.

This piece is effectively an instrumental pop piece. Recorded mostly with Roland sequencers, a Prophet 5 and a TR-808, it appears as a precursor of synth pop and ambient, having come out in 1982. The use of the sequencer to generate the background arpeggio, whether it was actually implemented on a Buchla or not, is also reminiscent of Buchla being the first to commercialize a sequencer in a modular synthesizer system. Buchla would end up repairing Ciani's specific system multiple times over the years - prefiguring synthesis technology as a service by a few decades ahead of MaxMSP and Ableton Live.

The microsocial of the piece itself - once again, a negotiation between the composer-performer and her machine - is here compounded by the sonic and cultural legacy of those machines. As this combination of her musical ideas and the realization these machines enables gets negotiated, the sounds, through this recording, become part of the macrosocial production of a woman composer in a male-dominated field, as well as the greater commercial market of 1980's specialized music labels.

4. Laurie Spiegel Drums (1975) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6qhlvRm4iG4

5. Laurie Anderson Two Songs For Tape Violin (1977) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IRGjtMZzCYo

Laurie Anderson (born 1947) also both composed and participated in the development of new electronic music systems. The system mentioned in the title of this piece, the tape-bow violin, consisted of the addition of a tape reading head to the traditional violin bridge, and the replacement of hair in bow with magnetic tape.

In this specific piece one can hear the forward and backward reading of different portions of tape: it would appear the beginning of the recording is a fairly unprocessed or unedited performance of the new system. The second element of the recording, a narrated story over a piano melody, blends a performance on the tape-bow violin, complemented with Anderson's spoken voice, a mainstay of her work throughout her long carreer.

The politics of making instruments are related to the politics of making music, in a complementary fashion. Yet, the research and press associated with non-male makers in music, or even any research on gender parity in electronic music instrument design, is only slowly starting to develop. Andra McCartney's 1995 Leonardo Music Journal article Inverting Images: Constructing and Contesting Gender in Thinking about Electroacoustic Music started a small thread that can be seen to continue in Tara Rodgers work and more indirectly in Georgina Born's, but no systematic review of this connection between gendered music production and gendered music technology production exists.

Laurie Anderson's work stands regardless of this lack of context. Her legacy as a unique figure between the New York avant-garde and the popular music world is incontestably valuable, but if we are to read music in relation to different levels of sociality, it seems we could perhaps appreciate the technological work she put into pieces like this one with more context about the role and access of different underrepresented communities in the historically classist and sexist practice of engineering. Other historical analysis on related topics exist: see for example, Kristin Haring's contextualization of the development of amateur radio in post-world-wars United States. Considering the close connection between that community and the electronic music world, the methodology and social dynamics described in that book could serve as a basis for an equivalent analysis of audio technologies, especially with the new critical eye afforded by Born's and Rodgers' recent publications and reflexions.

0 notes

Text

Response 7: Applying Georgina Born's four orders of relational musicology

Georgina Born is a British improviser and anthropologist, whose improvisation and cello practice has influenced her study of music as a social focus. In the 2010 article "For a Relational Musicology," she sketched out four orders at which sociality operate in and around music:

The first order equates to the practice turn: here music produces its own socialities in performance, in musical ensembles, in the musical division of labour, in listening. Second, music animates imagined communities, aggregating its listeners into virtual collectivities or publics based on musical and other identifications. Third, music mediates wider social relations, from the most abstract to the most intimate: music’s embodiment of stratified and hierarchical social relations, of the structures of class, race, nation, gender and sexuality, and of the competitive accumulation of legitimacy, authority and social prestige. Fourth, music is bound up in the large-scale social, cultural, economic and political forces that provide for its production, reproduction or transformation, whether elite or religious patronage, mercantile or industrial capitalism, public and subsidized cultural institutions, or late capitalism’s multipolar cultural economy forces the analysis of which demands the resources of social theory, from Marx and Weber, through Foucault and Bourdieu, to contemporary analysts of the political economy, institutional structures and globalized circulation of music.

(Born, 2010 p232)

In the next responses I'll consider some works and practices and start developing a relational reading of these achievements based on Born's article, as summarized this section from her article:

1. George Lewis - Voyager Duo 4 (with Roscoe Mitchell, 1993)

George Lewis (born 1952), is a Chicago-born improvisor and ethnomusicologist, involved in developing the Assiociation for the Advancement of Creative Musician, and in his own brand of interdisciplinary institutional research. Lewis and Georgina Born have known each other since at least the time of Born's project on IRCAM, based on a year of on-the-ground observation during which Lewis was also one of the composers in residence. In fact, Voyager - the piece of which we hear a realization here - is mentioned in Born's groundbreaking study of the institution, and offers a fairly appropriate place to start considering Born's methodological recommendation - the piece directly shaped the development of her framework.

Here, we have a complex digital improvisation system, designed by Lewis to improvise music based on phrases, and with the ability to both operate independently (without external stimuli) and listen (respond to stimuli in complex ways when it does exist). In this duo, Mitchell and Lewis are both improvising, and the computer is working along them.

That is the first layer of relationality at hand in Voyager. This piece is particularly interesting because it was designed with this question of agency in mind (Lewis, 1999). Lewis - one of the main thinkers on the topic of improvised music as the locus for negotiations of power not just between the participating musicians, but between cultures - brings in this concept of the independent music machine to blur how afrological conceptions of experimental sound can be realized in the academic and institutional realm still dominated today by what Lewis terms a "Eurological" tradition (Lewis, 1996). But at the micro level - that of the piece itself - the participants very much profess an Afrological heritage: Lewis and Mitchell are both longtime members of the predominantly Black AACM, and the computer software is designed expressly to parallel some of Jazz improvisation's non-hierarchical dynamics (Lewis, 1996).

This does not mean that the piece is not aware of its role in the context of improvised digital music, a middle ground still contested today in terms of representation and access. The piece was designed on Apple 2 computers at IRCAM - hardly the locus for an intersectional conception of music making. I also want to comment here on the timbres synthesized by the digital system: it's hard to realize how jarring mid-90's MIDI synthesis sounds in the context of two improvisors like Lewis and Mitchell. I was taken aback - and my understanding is people were back then as well. Lewis, in designing his system, made a conscious choice to emphasize the structure of how his system behaved, over a microscopic attention to timbre. This could be read as a response to spectralism, a movement whose entire focus began with a low-level attention to timbre. However, I also need to be aware of my reading of this as a white man growing up in France, with musical tastes that favored the "real instruments" and "no nonsense" approach to composition (which did not see kindly on improvisation). Understanding criticism as partially autobiographical helps clarify that once we consider music in its first and second orders of relations, we have to acknowledge the power structures dear to Lewis, but also those inherent in the perspective of the critic. In that sense, interviews with authors to clarify these questions can be useful. In the perspective of my own work, I believe looking at the code or circuits for the relevant systems can also be uniquely and valuably informative. However, in either case, the agency of the observer should be acknowledged as well and mitigated if necessary. In my case, the reality is my opinion on the MIDI aspect of Voyager as a synthesis engine is worthy of further investigation and inquiry outside of my own perception of it, warranting perhaps a specific question on that topic if I were able to chat with Mitchell or Lewis.

The third level of mediation might be found in Georgina Born's unexpected covering of this piece as part of her study of IRCAM, since Lewis was in residence at the same time working independently from IRCAM staff from their attic. The piece, and the background he would eventually provide through various post-facto publications, are clearly influenced by the class, race and gender dynamic at IRCAM as described by Born (Born 1994). Considering Lewis' perspective and eventual positions (this is multiple years before his foundational eurological/afrological paper) it is safe to assume that those societal dynamics at IRCAM comforted his interest in designing a non-hierarchical, partially autonomous computer system improvisation system. It is unclear how much of it was shaped by knowledge garnered from the local engineers, but Born's passages describing Lewis' work make him appear as fairly secluded. A relational account of Lewis work, as inadvertently prefigured by Born in her study of IRCAM, facilitates an understanding both of the piece's concepts, of the pieces context, and of the piece's impact.

Consider, then the eventually international reach of this piece and the scholarship it motivated, and this order of relationality becomes a necessity to account for. Born's fourth level, concerned with the large scale, connects with the concerns of the computer and the tools I mentioned above. Lets consider the machines that enabled this music, but lets also consider the machine that enables modern music making, along with everything else:

An organised system of machines, to which motion is communicated by the transmitting mechanism from a central automaton, is the most developed form of production by machinery. Here we have, in the place of the isolated machine, a mechanical monster whose body fills whole factories, and whose demon power, at first veiled under the slow and measured motions of his giant limbs, at length breaks out into the fast and furious whirl of his countless working organs.

(Marx, Capital Vol 1)

Marx' relevance in music criticism might seem heavy handed, but I think there is value in considering his perspective on production and labor in complement to Born and Lewis' focus on agency, through their common discussion of machines. In the case of Voyager, the machine helps improvisors from Afrological tradition negotiate a technology (the computer) and a performance environment (contemporary music) that was ostensibly designed without them, if not on the backs of their labor or of other wage-workers. The labor exerted by his machine brings in some of his perspective into the wider machine of music consumption and production, just like Lewis' academic writing slowly redefined how a small portion of academia came to reconsider the improvisational musical work through his publications and teaching. As Born states:

The four orders of social mediation are irreducible to one another; they are articulated in non-linear and contingent ways through conditioning, affordance or causality. While they are invariably treated separately in discussions of music and the social, all four orders enter into musical experience. The first two orders amount to socialities, social relations and imaginaries that are assembled specifically by musical practice. The last two orders, in contrast, amount to wider social conditions that themselves afford certain kinds of musical practice although these conditions also permeate music’s socialities and imagined communities, just as music inflects these wider conditions. In all these ways music is immanently social, as ethnomusicology has long demonstrated by testifying to those many musics of the world in which there is little separation between musical and social processes.

(Born, 2010, p232-233)

2. Hugh Davies - Music for a Single Spring (1975)

This was only a cursory treatment of Voyager through Born's relational lense, but even then, I'll attempt to apply to three more pieces in a more succinct fashion.

Hugh Davies (1943-2005) was a composer and musicologist today most famous for his homemade electronic or electroacoustic instruments. His Music for a Single Spring is much less documented and discussed than Lewis' Voyager, but I do believe this clarifies some of how Born's thoughts can be applied not as a complex theory but as a straightforward research method: first, lets consider who the players are: Davies, his single spring, and the various electronics clearly used in amplifying and recording the spring. This asks an interesting question which is that since Davies has passed away, how does the implied constraint of relying on secondary sources affect the historicization and analysis of this project? But beyond that, the conceptual possibility of roughly valuing each of these components in the performance system as small assemblage is quite straightforward, from the sounds themselves: listen to how the spring is activated, struck, processed: these are the relationships and properties Davies wished to explore. Second order: what is this piece's imagined community? In the case of Davies, a small community of experimental music makers in England - this introduces the question of timeframe, which Born also discusses in her paper. Third order: how does this piece mediate wider social relationships, if at all? Consider the resurgence of Davies' work in very recent scholarship, partially due to the committed work of his past student James Mooney. Fourth order: how is this piece bound up in larger social structures? How did it end up on youtube, for anyone to hear for free? How was it published in the first place? was it conceived with political goals, explicit or implicit? Did Davies see his practice as a way of democratizing instrument design and experimental composition?

3.Charles Dodge - Earth's Magnetic Field (1970)

Dodge (b.1942) is notorious for arguably being the first composer to sonify unrelated scientific data (here, readings about earth magnetic fields) as part of a piece. This sentence is enough to see how Born's four orders will play out: the composition itself is defined by the interaction between the composer and the machine (a mainframe at the composer's institution), realized by a score which is also a computer program, but then gets disseminated as a recording. The use of the computer, as Dodge was only a beginner programmer, is defined by the interaction of the people supporting Dodge and supporting the machine. But that machine was made for an international institution, using funds from a variety of sources and designed to serve a wide number of user's needs, which shaped how it was designed and what functions it could fulfil. That, in turn, was shaped by a particular western conception of mathematics, decision making, and interactivity.

Each of Born's four orders can be linked to a particular aspect of Dodge's work, each time revealing specifics about both Dodge, his process, and the computer. His idea and ideals are mitigated by "hard diplomacy" of what it can mechanically operate and the "soft diplomacy" of the people working to help Dodge achieve a reasonably satisfying goals. In this sense, I see electronic music composition as a compromise between the agency of the composer, itself culturally and ideologically shaped by its social environment, and the agency of the machine, which is literally assembled by other humans which transfer to it some agency to be interpreted at a later date. The second quote from Born, as well as the discussion of temporality in her article, makes it clear that the orders she describes are interdependent and related: I believe it is because the object of interest - the music - is the compromise of all these nested agencies, weakly affecting the result through a variety of intermediaries which distort the original properties and intents.

4. Iannis Xenakis - Metastasis (1955)

Xenakis (born 1922) is a foundational figure of the 20th century's western contemporary music. His background in architecture has led not just to many connections between sound and space as justified by his work and thought, but also in a variety of purpose-designed environment, such as the 1955 World Fair Phillips Pavillion. The multichannel system it contained, combined with the never-reproduced shape of the space, means we'll probably never hear Metastasis as it was heard there.

In relation to Born's four levels with which to consider musical works, I think this is particularly relevant. Indeed, this work can be performed like many others: there is a score, and a tradition of performing this score, with model recordings to serve as examples. The graphic score is somewhat unusual but not out of place in Xenakis' oeuvre. However, this is also a piece that has a certain meaning because of its presence in this disappeared space, a deeply social experience. As such, the microsociality of the piece and the 2nd order modes of experiencing the piece are, or were, deeply related, in a way which means the rest of the context in which it occurred can really only roughly imagine what it must have been like. Sven Sterken writes of the piece:

In Notes sur un geste électronique, published 40 years earlier, he described for instance an isotropic acoustic space paved with speakers. His aim was to disconnect the aural experience from the physical presence of the architecture, the audience, instruments and the musicians. Consequently, this text already announces Xenakis’ abstract approach to listening. Thus, the statement above is only a radical reformulation of his vision of a proto-virtual listening situation, providing a context for the listener to become only ears.

(Sterken, 2007)

If I am interested in how circuits and computer code can prescribe musical works, this is a clear case of a how an abstract space can affect a musical work, which I would see as related. Xenakis, in choosing to reference directly what Born would eventually come to call the second order of relationality in music, decided to let it shape his work, composing for his concept in addition to himself. This, in turn, influenced both how the musical work was received as groundbreaking for his time, but also to this day has a lasting legacy on the way people perceive contemporary music as a whole.

bibliography:

Born, Georgina. "For a relational musicology: music and interdisciplinarity, beyond the practice turn: the 2007 Dent Medal Address." Journal of the Royal Musical Association 135, no. 2 (2010): 205-243.

Lewis, George E. "Improvised music after 1950: Afrological and Eurological perspectives." Black music research journal (1996): 91-122.

Lewis, George E. "Interacting with latter-day musical automata." Contemporary Music Review 18, no. 3 (1999): 99-112.

Sterken, Sven. "Music as an art of space: interactions between music and architecture in the work of Iannis Xenakis." Resonance: Essays on Intersection of Music and Architecture 1 (2007): 21-51.

youtube

youtube

youtube

youtube

0 notes

Text

On making music most people will dislike

Gordon Mumma - Cybersonic Cantilevers (1973)

Mumma (born 1935) is, to me, one of the underappreciated peripheral figures of the New York scenes centered around Cage and Tudor. The maker and designer of many devices used or modified by Tudor, he was the one to introduce the latter to semiconductors after vacuum tubes proved to be too much for the pianist (source: chatting with Nic Collins).

Here are the liner notes for the New World Records 2005 Gordon Mumma release:

Cybersonic Cantilevers (1973) extends his resourceful use of live-electronic processes to include the active participation of audience members, many of them children and teenagers who were quick to grasp the artistic potential of cybersonic technology.

http://www.newworldrecords.org/album.cgi?rm=view&album_id=15052

The piece begins with an electronic stutter covering a faint background hum, eventually (d)evolving into a full on electronic orchestra of syncopated perscussive sounds washing against a drone, with a few vocal stutters along the way. Eventually, the percussive sounds fade away, giving back way to a sparse stutter from the beginning of the piece. The last 10-12 minute of the piece then center around this modulated drone, peppered with bleeps, scratches and sub-bass rumbles.

Although I've grown fond of listening and making music "like this" - music with no song structure, music exploring a process, music about offering a set of interactions to an unpredictable force - I forget that to most people not involved in making this type of work do not hear the point of this. My grandma tends to ask me "at which point does the melody come in?" Experiments in Art and Technology (EAT) were the height of this "panacea that failed," as systems-theorist and artist Jack Burnham would eventually qualify it. The criticism hasn't changed much: people coming from listening to pop music ask if the song ever start, while those up for a bit of a challenge feel like the disconnection between the underlying concept (whatever it may be) and its usually abstracted form are disappointing at best. "You don't leave half the argument up to the audience to figure out" said my Science and Technology Studies professor when summarizing his criticism on avant-garde music.

youtube

David Behrman - Wave Trains (1966)

This becomes almost limpid in David Behrman's 1966 piece Wave Trains, in which Mumma controls the electronics (transducers and microphones creating a feedback loop around a piano). Assuming Behrman is at the piano, and Mumma at the electronics, you can hear them clearly interact through the common medium of the piano's string and frame. The closed loop of the system means hierarchies are agreed upon and negotiated throughout the piece. The relative lack of traditional "piano sound" means that Behrman - the official composer for this piece - is mostly interested in the sonic consequences of that negotiation. You mostly can differentiate the clear feedback from the overtoned resonances, and you can hear them interact - the blurring of responsibility is equivalent to a blurring of timbral identities.

Again - this is work I'm happy to listen to, because my personal history in and around these practices has shaped my listening to appreciate this type of interaction as represented through sound. I would love to learn about what precisely the piano was, what the microphone was, what the transducers were, if there is any type of instruction from Behrman, and maybe even try to reperform this piece - but I've also come to accept that I am in a minority, and that perhaps this is why Mumma remains an underappreciated figure in my eyes: no moment of fame with a Sitting in a Room or 4:33, and no commercial breakthrough a la Oh Superman. Same could be said of Behrman, whose work I'd qualify as the electroacoustic parallel to Mumma.

youtube

Nic Collins - In Memoriam Michael Waisvisz (2009)

Nic Collins (born 1954) is part of the younger generation of people who worked with Alvin Lucier and David Tudor after Behrman and Mumma. I saw this piece performed multiple times before know what exactly it referenced, and before I understood Collins' position in this type of practice: I genuinely enjoyed this piece. I was just familiar enough with the modes of operation of the square wave oscillator attached to the photocell controlled by the candle to know exactly what was happening (40106/4093 circuits built from his book Handmade Electronic Music have a distinctive timbre because of the specific pulse-width they end up producing, as I'd learn from Nic).

Reading about Michael Waisvisz, a colleague of Nic's during his tenure at STEIM, you understand both something about these friends, their respective personalities, and interactions (it takes special people to dedicate a dramatic whiny toy performance in your honor, and perform it many many times, after your death). I find something particularly touching about a piece which so humorously captures a relationship probably based around jest and playful professionalism (these are, after all, two people with careers of making strange sounds with other people) and yet achieves profoundness with building blocks as silly as a birthday cake candle and a personal battery powered fan (as Nic walks around the candle, the flame squiggles and dances, affecting the tone of the oscillator. He occasionally walks very far, chaotically triggering small air currents across a room, with his hand held electric fan, occasionally climbing on chairs and tables to gain elevation).

And yet, once again, for people not personally invested in this practice or these people, this would probably make little sense. Nic knows that, so do Mumma and Behrman. They've all negotiated their careers so that they could afford to limit their audiences to those interested and the few souls those followers could bring along with them. Nic has achieved this partially through institutional recognition, while Behrman and Mumma have maintained peripherally academic positions and found ways to support their art through other means. This is, to some extent, a privilege, one they've worked hard to achieve and preserve, but a privilege nonetheless. Nic's book has made it to the hands of countless musical electronics nerds, and therefore affected the microsociality of contemporary electronic music making. Through him, Mumma and Behrman's influence has reached those practice too - but overall, these three practitioners are in Laurie-Anderson-before-O-Superman areas of recognition in the mainstream.

youtube

Paula Mathusen - But because without this (performed by the dither quartet, 2011)

Paula Mathusen's work for four guitars (she rescored this for the Dither quartet's format) is a lovely piece, of the right length, playing on the tropes that got me into experimental music (the fine line between guitar noodling and composed piece). Again, I can explain why I like the piece, why each turn reminds me of just the right parts of Morricone soundtracks with and the ruthlesslness of Dylan Carlson's riffs in the band Earth but more playful. Mathusen scored the piece entirely, it is intriguing for me to imagine the notation for extended technique guitar, and even just to imagine playing from a score in general.

But this piece points out another aspect of "unusual" music making as a practice that can offer a point of entry to those not naturally inclined to 8 minute guitar quartets with no song structure or lyrics might consider. Mathusen, by picking guitars, has to contend with a culturally charged timbre and set of compositional options. We can safely assume that Mathusen has heard guitars in a pop music context before, just as we can assume that at some point, Mumma, Collins and Behrman have listened to and enjoyed a top fourty track of some year. Over time, all these composers departed from the majority decisions in terms of what they wanted to hear, and they all did this differently. With each piece from each of these composers, you get a glimpse of how they might have departed, and how far they are away now, and how this is not a linear or logical process: they get to back, jump forward, explore new compositional concepts at will - it's their job. Most pieces are somewhat autobiographic, I appreciate these because they acknowledge the role of some objects in these sonic storytellings (Mumma's Cybersonic systems, Behrman's piano, Collins' oscillator and flame, and Mathusen's guitars), but in terms of composing for a varied audience, I would posit that finding artefacts or processes which can be perceived in a varied set of ways that will seem personally relevant to a wide variety of people is perhaps the best way to engage an unsuspecting audience.

youtube

We were lucky enough, last week, to get Bonnie Jones in the Open Source Art, Music and Culture class I TA. In her lecture, she described how she really viewed her practice as a direct consequence of her upbringing. She gave us details on the context in which she grew up, but also details of the music she chose to listen to or be engaged in as she was growing up.

youtube

One of the students asked her at what point she went from using guitar pedals the regular way, to “the other way:” she described some musical experiences that, put together, made it seem unnecessary to keep working with the structures she had simply assumed were part of music making. The result is an abstraction of where that negotiation, between how she got to develop her own tastes and the confines of what was made available to her (both musically and materially) which can be heard through sound. There is a lot more to hear, but: in a nutshell, this is the wordless storytelling I am interested in.

0 notes

Text

On Surface Music

Christian Marclay (born 1955) owes part of his fame to a record of him DJ'ing, which was sold in 1985 without any type of protective sleeve, and titled "Record Without a Cover" (1985). As the record sat on shelves and stores, dirt and damage changed the sound of each copy in unique yet similar ways. Marclay detailed in an interview with Douglas Kahn the origin of this project:

Kahn: Could you tell me how you began making art and music with records?

Marclay: At the time I was already thinking about sound; this was 1978. I was living in Brookline; while walking to school on a heavily trafficked street a block away from my apartment I found a record on the pavement. Cars were driving over it. It was a Batman record, a children’s story with sound effects. I borrowed one of the turntables from school to listen to the record. It was heavily damaged and skipping, but was making these interesting loops and sounds, because it was filled with sound effects. I just sat there listening and some kind of spark happened.

I think this is my favorite iteration of Cage's "listening to the sounds of 5th Avenue:" in this version, the human and natural destructive forces left abstract marks on the Batman record, before being re-presented to Marclay as music (sound?). There is an additional step which abstract the environment's influence by making it material. This indirect and lossy process, by which the action could rarely ever be recovered from the inscription on the record, is enough to turn an interest for the mundane (everyday life) into a morbid fascination of the the impermanence of our commodity culture rendered as sound. Remembering Feldman's comment about whether we chose to control the materials or control the experience, Marclay clearly has made a choice here.

From this almost autobiographical interest in self-destruction (at the scale of the human race) music seems to have gone a long way since Marclay's coverless record (a good pun, too, considering that it's made entirely of samples). Maria Chavez' practice as a turntable performer, not of broken records but of manufactured devices that happen to be modified records, offers a hint of what getting just a little bit of control back can do.

I saw Chavez perform as part of a concert at the Friedman gallery which included Pauline Oliveros and Seth Cluett in 2016. She played the vinyl mat, various records of (seemingly) silence, occasional looping records and other materials. The particularly surprising element was the use of a double stylus play head, which picked up sound from two different positions on the record and played them simultaneously.

Chavez embraces the use of damaged or worn styli:

Besides other methods, you work a lot with broken or damaged needles, you call them “pencils of sound.” How and when did this approach and practice come about?

MC: This approach started when I was performing early on. I remember I was dragging a needle across a record and somehow the tip of the stylus got caught on a deep scratch and bent itself. But I had been dragging the needle across the record for a while so the stylus was warm, I think, and it twisted into a standing position and travelled across the vinyl on it’s own, like a ballet dancer. As the needle began to glide across the grooves of the record, it was still reading the sound that was cut into the vinyl.

This situation opened the door to understanding how a needle breaks in certain situations. I encourage breaking but I don’t force the stylus to break. When one forces a needle to break it tends to break in the same way, clean off. But when one encourages the break by creating circumstances, that is when it morphs into other interesting needle configurations. This is why I refer to them as “pencils”: a pencil can break in different ways and can also wear itself down. I also tend to hold the needle arm like I hold a pencil in some of my techniques, hence the comparison.

This playing is something that Chavez has developed over years of performance and practice, slowly learning how to break or wear down styli, how to get them caught in vinyl grooves, how fast they would wear beyond use… The fragile equilibrium of "broken in" styli to Marclay's "broken out" records are complementary practices.

Graham Dunning (born 1981), in comparison, maximizes a use of the turntable itself, but as a mechanical tool rather than an electronic one as a DJ would. By stacking modified records using spacers and using multiple styli / contact mics in addition to a wide array of things from plastic spikes to ping pong balls, Dunning takes advantage of the heavily regimented cyclic nature of techno to make it out of organized machine sounds. He DJs like most DJ DJ, but his crates are full of foam, chemistry apparatus and tentacular microphones rather than records.

By conceiving of techno as a cyclical process, Dunning hints at the connection between the grooves in the record and the natural groove of this machine turning a platter. In a way, between the three of them, they've taken advantage of each of the components available in a record player: the record, the needle, and the player itself (although I have yet to see a voltage controlled speed control on a turntable - analog pitch warps as part of a modular setup seems potentially promising?).

The figure overshadowing all these practices, of course, is John Cage (born 1912) and his Cartridge Music (composed 1960):

In Cartridge Music, the performer is instructed to insert all manner of unspecified small objects into the cartridge; prior performances have involved such items as pipe cleaners, matches, feathers, wires, etc. Furniture may be used as well, amplified via contact microphones. All sounds are to be amplified and are controlled by the performer(s). The number of performers should be at least that of the cartridges, but not greater than twice the number of cartridges. Each performer makes his or her own part from the materials provided: 20 numbered sheets with irregular shapes (the number of shapes corresponding to the number of the sheet) and 4 transparencies, one with points, one with circles, another with a circle marked like a stopwatch, and the last with a dotted curving line, with a circle at one end. These transparencies are to be superimposed on one of the 20 sheets, in order to create a constellation from which one creates one's part.

The (relatively) complex, indeterminate graphic score and hoarder-like setup of the piece seems almost inelegant in comparison with the practitioners above, even Dunning's ping pong ball collection. Paraphrasing one of Cage's later aphorisms, it is as if he was the only one who could give someone permission to do whatever he wanted.

All of these practices and works, in a way, use surface sound to intuit something that is under the material surface of these now amplified objects. For Marclay and Chavez (who've worked together) it's about the inherently self-destructive nature of the vinyl record and its needle, literally dancing to dullness. For Dunning and Cage, there is some aspect of accumulative maximalism, building objects/sounds on top of sound/objects. Dunning might be the one closest to a popular music tradition, but his method are arguably just as challenging as Cage's score (and listening to his performances, it's easy to hear how inconsistent playing the vinyl scratch and pop sounds can get. In retrospect: of course Cage has a piece for turntable cartridges. It was a surface tradition waiting to get started.

http://econtact.ca/14_3/schick_chavez.html

http://johncage.org/pp/John-Cage-Work-Detail.cfm?work_ID=36

Feldman, Morton. Give my regards to Eighth Street: collected writings of Morton Feldman. Exact change, 2000.

youtube

youtube

youtube

youtube

0 notes

Text

On compositions as assemblages

Robert Ashley, Automatic Writing (1979).

Robert Ashley (born 1930) is an experimental composer, performer and theatre artist who was one of the originators of Ann Arbor's ONCE festival (1961-1969). He is notable for compositions that acknowledge and played off of the environment in which they were performed, making space one of the parameters for which his works were designed. Commenting on his preface for the composition Vespers by Alvin Lucier, David Toop paraphrases:

You can’t hear Vespers on a recording, he says, because the experience of hearing the music comes from the space in which it’s performed. He also talks about attempts to subvert the concert hall or redesign concert halls specifically for experimental music, as if it’s going to stand still for another hundred years to please the architects. He talks about fire marshalls. Basically, if you think you’re being subversive but at the same time pleasing the fire marshalls then you’re not subverting much at all.

Automatic Writing (1979) is a piece focusing on involuntary speech and miscellaneous by-products of Robert Ashley's voice, it is one of his many works dealing with multiple levels of context and interpretation. As in Wolfman (1964), electronic amplification of sound is essential to the work, allowing meaning and sound to be re-presented on equal ground rather than with a hierarchy. The work was prompted by Ashley's depression, itself caused by a lack of interest from the public:

I was out of work, so I decided to "perform" involuntary speech. The performances were more or less failures because the difference between involuntary speech and any other kind of allowed behavior is too big to be overcome willfully, so the performances were largely imitations of involuntary speech, with only a few moments here and there of "loss of control." These moments, triumphs for me, are documented elsewhere, in rumors and in legal briefs against my behavior on stage. Commonly, for instance, people think that involuntary speech is a symptom of drunkenness. (Watching people on the subway who are engaged in involuntary speech behavior and who obviously can't afford to get drunk should be enough to teach that drunkenness and involuntary speech are different, but we can't see that logic.) This is dangerous territory for a performer. It is against the "law" of our society to engage in involuntary speech. That's why we are embarrassed to talk to ourselves. That's why Tourette had to leave the room. That's why we are embarrassed by poetry.

Automatic Writing is a good example of an auditory assemblage, prompted by a complex socio-cultural, personal and technological situation. Manuel DeLanda, quoting Deleuze, defines the assemblage as "a multiplicity which is made up of many heterogeneous terms and which establishes liaisons, relations between them, across ages, sexes and reigns – different natures." Ashley mediates his raw, personal experience of Tourette's syndrome through multiple levels of performance (instances of this work prior to recording), re-iteration (the voices heard are mostly that of Mimi Johnson, but based on his original utterances), technology (a polymoog, as well as a switching circuit by Paul DeMarinis, whose purpose is unclear), and spaces (the artificial environment recreated through the mixing process, the unclear provenance of the bass). All the different natures - none more valid or invalid than the other - negotiate their uneasy coexistence in this piece, as they do in real life.

"Allez laisse toi aller" (come on, let yourself go) murmurs Mimi Johnson after the 5 minute park. Not a suggestion, rather, an order: this assembled composition can be heard as a playful encouragement for the these natures to stop torturing their host.

https://www.allmusic.com/album/ashley-automatic-writing-purposeful-lady-slow-afternoon-she-was-a-visitor-mw0000168923

https://davidtoopblog.com/2014/03/09/automatic-writing/

https://www.dramonline.org/albums/robert-ashley-automatic-writing/notes

http://www.lovely.com/titles/cd1002.html

"AUTOMATIC WRITING" (1979)

Voices: Robert Ashley and Mimi Johnson.

Electronics and Polymoog: Robert Ashley.

Words by Robert Ashley.

French translation by Monsa Norberg.

The switching circuit was designed and built by Paul DeMarinis.

Produced, recorded and mixed at The Center for Contemporary Music, Mills College (Oakland, California), The American Cultural Center (Paris, France) and Mastertone Recording Studios (New York City) by Robert Ashley.

Mixing assistance at Mastertone Recording Studios by Rich LePage.

A mix of the monologue and electronics was used in the video tape composition, "Title Withdrawn," (from "Music with Roots in the Aether, video portraits of composers and their music") by Robert Ashley.

Harry Partch, Chorus of Shadows (1964-6)

Born 1901, Partch is perhaps most recognized for his embrace of microtonality, as exemplified by his signature 43 note scale, which resulted in a number of custom built instruments and the vast compositional catalog illustrating the potential for this theoretical systems and the corresponding objects.

Chorus of Shadows is the second piece in a Noh-inspired opera title Delusion of the Fury, drafted in 1964 and refined in 1965-66. Here the assemblage might not be as heavily space-dependent or based in electronics, however, discussing the music as an assemblage does offer a fitting structure for separating the main elements of this sub-component of the work.

Some of the natures at hand are cultural natures: the influence of Noh theater on a US composer in post-WW2 context is a worthwhile discussion which might itself be read as the deconstruction of another complex assemblage.

Other natures are more directly musical: this is the piece which required the most manufacturing in terms of the number of instruments. The literal embodiment of this margin between a traditional Japanese drama story and its implementation by an American, these instruments show how cultural influences were negotiated in this piece through technical means: not by simply playing japanese melodies on western instruments, or by adapting the music to western scales, but by transferring both contexts to a third, more unique sonic framework. Harry Partch's scales offer a mediation of the two cultures through a material and sonic interface.

Lali Barriere, Marta Sainz (as Un Coup de Des): 001 (2013)

Improvisor duo Un Coup de Des (A throw of dice) is a late-2000's group composed of Lali Barriere, an electroacoustic musician, and Marta Sainz, an experimental vocalist.

001 acts as a contemporary reiteration somewhere between Ashley and Partch. Meaning and tonality are not of importance here: the duo is aware of these values having been dissolving for a few decades of experimental sound. All that is left is amplified things: the human voice is presented along the mechanical voices of amplified objects. The clear reference here for me is Pauline Oliveros' Apple Box and Apple Box Double, composed by Oliveros for her then as a duo with David Tudor (Oliveiros and Tudor were both friends with Robert Ashley). Just like Cage's Cartridge Music, all these works take advantage of electricity's potential as an abstract magnifying glass via sound.

The concept of assemblage is once again a natural fit for this semi-improvised performance of a semi-improvised collection of objects, spaces, circumstances. The depth of field is provided almost exclusively through the acoustics of the performance spaces, and the collection of amplified materials is clearly related to the everyday realities of the performers (cutlery, balls, bowls, wooden boxes, etc.). The site-specificity of the acoustics are mirrored in the site-specificity of the objects. The unique experience of the audience witnessing an improvisation mirrors the uniqueness of the situation for the performers.

Reading musical performance systems (and including sociocultural contexts, rather than simply technical and acoustical ones) as assemblages suggests a specific type of improvisatory expertise, one not bounded exclusively by responding to musical cues, but also to abstract and openly-interpretable extra-musical and extra-temporal cues.

Throbbing Gristle: United (1978)

Throbbing Gristle (formed 1975) reminds us (at least with this track) that these values and hyper-specific readings of experimental sound does not necessarily get in the way of making pop music, or something close to it. Ostensibly working from a synth-pop structure using exclusively synthesized instruments and voice, Throbbing Gristle occasionally fades in Kraftwerk-like noise swells and vocal samples more typical of their early work. Yet, being familiar with their early work (like the album Second Annual Report, from 1977) or the politics of some of the group's members will make forays into accessibility perhaps even more jarring than their other output.

In that sense, reading musical works as assemblages of assemblages is ultimately perhaps somewhat confusing in terms of the power dynamics underlying each of these works as negotiations of personal ideas and societal contexts. If everything is a web of webs, it becomes difficult to keep track of what some of these overarching societal zeitgeists were, just like it's easy to lose sense of whether Un Coup de Des might be catchier than some of Throbbing Gristle's output, and whether or not that's even a useful question.

Robert Ashley - Automatic Writing: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Rh_TC8j_JkE

Harry Partch- Chorus of Shadows: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3gtIEzBp_UA

Throbbing Gristle: United: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5XpqCxJZdGs

Lali Barriere / Un Coup De Des: https://soundcloud.com/lalibarriere/sets/uncoupdedes

0 notes

Text

Listening #3: learning to play nested environments (technical and natural)

James Tenney - Analog #1 (Noise Study) (1961, Bell Laboratories)

vimeo

I learned to hear these sounds more acutely, to follow the evolution of single elements within the total sonorous “mass,” to feel, kinesthetically, the characteristic rhythmic articulations of the various elements in combination,etc. Then I began to try to analyze the sounds, aurally, to estimate what their physical properties might be drawing upon what I already knew of acoustics and the correlation of the physical and the subjective attributes of sound.

Tenney (born 1934) is widely considered as the first composer to make a piece of purely digital music, Analog #1. Zavagna et al. deconstruct the piece along multiple axes in their 2015 paper, but the point of interest here is the parallel development of Tenney’s understanding for his living environment (specifically, the trip between his Manhattan home and Bell Labs in Murray Hill, via the Holland Tunnel) and his work environment, the MUSIC-III system as assembled by Mike Matthews.

In the quote above, Tenney describes his learning to enjoy and productively experience the sounds of the Holland Tunnel, which links New Jersey and New York by going under the Hudson. The experience will seem familiar to those acquainted with the early works and philosophies of Pauline Oliveros and John Cage: attentive (deep?) listening allows for a new, productive perspective on traditionally unpleasant sounds.

Tenney had no necessity to find beauty in the resonating white noise of his daily commute, yet this gentle self-discipline parallels his effort of learning still-developing MUSIC-III. In this iteration of the software, Matthews introduced the concept of unit generator, or u-gen. These u-gens enable Tenney to implement an instrument, which he would re-use in later pieces and describe in his 1963 article Sound Generation by means of a Digital Computer:

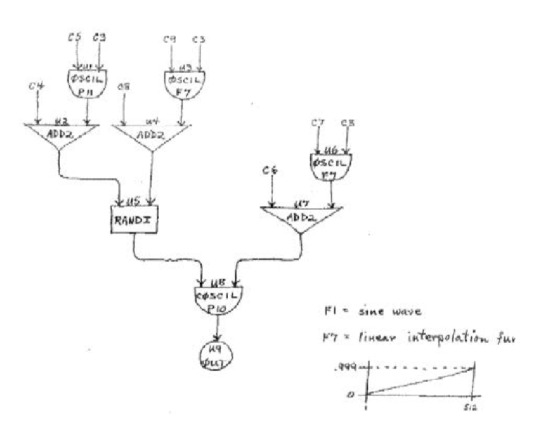

Unfortunately Noise Study used custom u-gens for which the code has been lost (Zavagna, 2015), but this diagram show the basic signal flow for each of the 5 digital instruments (Music-III works based on an orchestra/score separation, and Tenney used 5 copies of this instrument for Noise Study). Oscillators are mixed, some via a Random u-gen, and then processed further. Tenney adds:

For center frequency, the toss of a coin was used to determine whether the initial and final values for a given note were to be the same or different (i. e., whether the pitch of the note was constant or varying). In order to realize the means and ranges in each parameter as sketched in the formal outline, a rather tedious process of scaling and normalizing was required that followed their changes in time.

The multiple levels of indeterminacy form a second parallel with Cage. Tenney is using the semi-chaotic nature of the tunnel as a prompt to make sense of the possibilities offered by Music-III.

http://www.musicainformatica.org/listen/james-tenney-selected-works-1961-1969.php

The remake of James Tenney's Analog #1: Noise Study, a didactic experience - Paolo Zavagna, Giovanni Dinello, Alvise Mazzucato, Simone Sacchi, Dario Sevieril - LIEN, 2015

http://www.allmusic.com/composition/analog-1-noise-study-mc0002498856

Kahn, Douglas. "James Tenney at Bell Labs." Mainframe Experimentalism: Early Computing and the Foundations of the Digital Arts. MIT Press, 2012: 131-46.

Tenney, James C. "Sound-generation by means of a digital computer." Journal of Music Theory 7, no. 1 (1963): 24-70.

Ellen Fullman - Flowers (Through Glass Panes, Important Records, 2011)

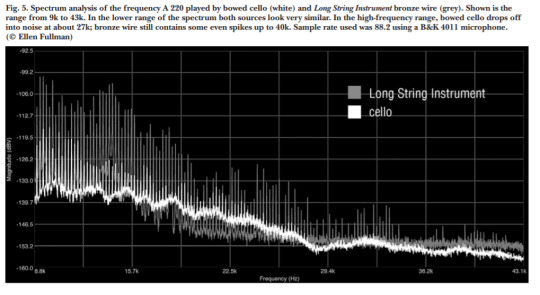

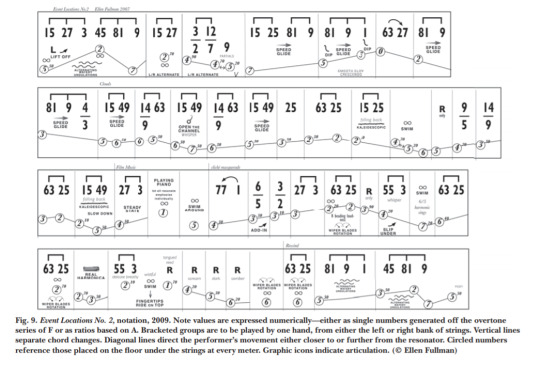

A composition made using the long string instrument made by Fullman (born 1957) and featuring violin and cello, this reflects a lifelong practice of experiencing a natural system (that of the long strings) and exposing this knowledge through sound.

Justin Yang, lecturer in the arts department at RPI, was explaining to our class today that visiting Fullman’s lecture made him realize how much skill playing the long string instrument takes. Rosin gloves are an odd way to play strings - Justin described how although he could get the strings to resonate, the overall output of his interaction with the system was overall “pretty terrible” compared to Fullman: he concluded that just like with other systems, the long string instrument offered space for expertise. Fullman had dedicated her career to it because it deserved that level of attention.

Rather than using insight from an existing physical system to illuminate a constructed, digital one like Tenney, Fullman is reframing traditional acoustic instruments (violin, cello) in the context created by her long string instrument.

Fullman, going further than simply comparing timbres as in the diagram above, elaborates:

I have the sense that my instrument is an open system, responsive to frequencies being played by other musicians and by the resonance of the room itself. When another musician’s sound reinforces my tuning, I can even feel a buzzing energy driving my strings to resonate using very little pressure from my fingertips. A dead room is very unflattering to the sound of my instrument. The Long String Instrument is complemented by a resonant room, unlike a cello, for example, which has a self-contained resonance and beauty of tone within its own body that a resonant room merely enhances. The artifacts that my instrument produces are at the core of my work. I find myself feeling lost in a dead room; I do not know how to move. It is as if my instrument itself has disappeared like a phantom, because I think I am actually playing the resonance of the room.

Here we have a different agencement of environments: the long string instrument, interacting with her, the other musicians and their instruments, all interacting with the space. By making the resonant body of her system the room in which she installs her system (rather than an artificial electronic tunnel like Tenney does) the implementation of this learning is different, but the modes of investigation offer parallels.

Fullman, Ellen. "A compositional approach derived from material and ephemeral elements." Leonardo Music Journal 22 (2012): 3-10.

György Ligeti - Artikulation (composed and notated 1958)

Ligeti (born 1923) and this early piece explore another environment, that of language, as mediated through electronics. One of his few Cologne pieces, he describes it as:

'Artikulation' because in this sense an artificial language is articulated: question and answer, high and low voices, polyglot speaking and interruptions, impulsive outbreaks and humor, charring and whispering.

Elaborating on the modes of productions of this piece in another publication:

First I chose types [of noise, or artificial phonemes] with various group-characteristics and various types of internal organization, as: grainy, friable, fibrous, slimy, sticky and compact materials. An investigation of the relative permeability of these characters indicated which could be mixed and which resisted mixture.

Again, we have the exploration of a natural phenomena (speech) through the lens of an abstraction (a phoneme-deconstruction of language) and expressed through the creative use of a technology.

The parallel between Rainer Wehinger’s post-facto score for Artikulation and the one devised by Alvise Mazzucato for Tenney’s Noise Study also offers another point of comparison relevant to this concept of environmental exploration. Beyond the straightforward stylistic commonalities and differences, these scores, along with Fullman’s unique notation system, reflect the paths used to traverse these environments and the exploratory nature of that travel.

Éliane Radigue - Usral (1969)

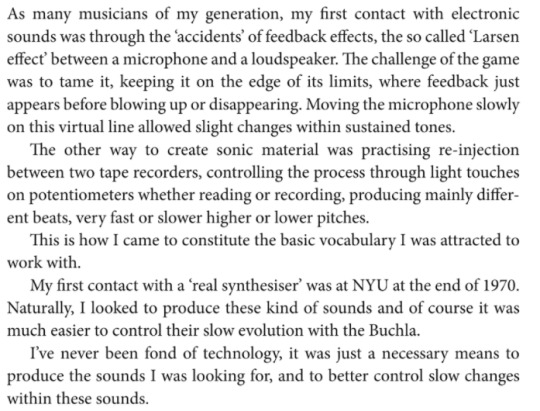

Artist’s statement from the Cambridge Companion to Electronic Music

Radigue’s early work is composed of recordings of feedback loops as re-framed by thorough tape-editing. Radigue (born 1932) decided to exploit her ability to manipulate the feedback sound of a microphone aimed at speaker. She used this material as the building blocks of compositions, though the use of tape editing techniques. Having met and socialized with Tenney, and seen the early days of Musique Concrete in Paris, Usral very much fits within the systems exploration of the pieces discussed above. In this case, the organization of sound is a thoroughly personal choice, and yet she uses the word vocabulary in the above statement, offering a connection to Artikulation.

Radigue’s musical language - not based on artificial phonemes like Ligeti, but rather closer to the drones of Fullman’s string instrument, exposes her development of an affinity for the sustained sound afforded by feedback and her intellectualization of a possible structure to fit it in.

This new combination of used / modeled systems - electroacoustics and purely electronic, pushes us in the direction of a taxonomy of played / inspiring enviroments.

http://daily.redbullmusicacademy.com/specials/2015-eliane-radigue-feature/

A potential criticism of this critical angle is that, well, a fair amount of contemporary music is concerned with the “exploration” of systems. However, a taxonomy of the architectures of technology and listening that make up this underlying trend in electronic sound could probably still use some organizing (at least in this post). Let’s go back over the models / implementations for each piece:

Analog #1: human system (holland tunnel), mediated by MUSIC-III

Flowers: natural system (a resonant room), mediated by Fullman’s long string instrument (a human system) in coordination with occasional traditional instrument.

Artikulation: speech (a natural system) as re-imagined by Ligeti through electronic sound (an electronic system).

Usral: electroacoustic phenomena (feedback) as re-presented by Radigue and her tape players.

This space may be more than 3 dimensional, working with spectra rather than binaries. There is a human dimension, an electrical dimension, and a constructed dimension, perhaps more. Just like instruments define the musical space within which a performance or composition can operate, these “environments,” whether imagined or real, define the ideological space in which that instrument is used. Each composition can be read as a compromise, or intersection of those spaces at a particular time. Mathematicians build abstract models of reality to better understand an aspect of it, knowing (usually) that the simplifications made along the way sacrifice some of the model’s overall accuracy to the benefit of more precisely representing one of the underlying phenomena. In this case, these creative machines, as George Lewis would call them, allow each composer to reduce the freedom offered by a musical practice into a more manageable space for them to explore.

youtube

youtube

youtube

0 notes

Text

Listening #2.5: musical ruthlessness

On September 22nd, 23rd and 24th, I saw / heard three shows in three different cities:

Yarn / Wire performing two Enno Poppe works, Feld and Tonband, a collaboration with Wolfgang Heiniger. (EMPAC in Troy, NY).

Cap’n Jazz (Brooklyn Steel, Brooklyn, NY)

Majority Rule and Pg.99 (First Unitarian Church, Philadelphia, PA).

Enno Poppe (born 1969) is a German composer and ensemble director.

Cap’n Jazz is a band from Chicago, IL, originally formed in 1989; Majority Rule and Pg.99 are bands from the D.C. area formed in 1996 and 1997 - these groups were all on reunion tours. The show in Philadelphia I saw with MajRule and Pg99 was a benefit for a local non-profit, Juntos.

I tried finding recordings of works by Poppe that got close to Feld, without real success. The moments around 4:55 in Filz are close, but not sustained for anywhere nearly as long as in Feld.

youtube

This is the sense in which I viewed his new work as ruthless: not taking any breaths, not giving up on some musical ideas and motives, and making the performers give a physical work just as much as an emotional one. The closest parallel I have is Vicky Chow’s performance for Tristan Perich’s Surface Image, and punk music shows.

youtube

This ruthlessness - not necessarily one that includes moshing or complex avant-garde qualities - is the clear connection in the unrelenting bleeps of Perich’s work, the unabashed enthusiasm of Feld and the shameless off-key screaming of Cap’n Jazz that would eventually turn into the shrieks and growls of MajRule and Pg99.

youtube

Poppe’s music isn’t childish, and Mike Kinsella’s demented lyrics for Cap’n Jazz have nothing to do with Pg.99, but I felt equally sucked in by the musically unforgiving decisions made by each composers. Entrainement in music theory is defined as the progressive synchronization of two rhythmic processes, I argue here that these pieces were various instances of a social entrainement, where emotional affect is slowly but effectively communicated. Listen to the 18:28 mark and after in “Progress of Elimination” of the David Frost Majority Rule album linked below, or to the “Take On Me” cover by Cap’n Jazz in the album above: it does not matter if you personally enjoy them, all that matters is that a crowd of a few hundred people at the shows went batshit within .5 seconds of their start.

In the case of a new piece, or a piece difficult to apprehend as having “refrains”, like Feld, this is attained through variations in repetition and a game of rhythmic / melodic expectations. In the case of Cap’n Jazz bizarre Punk and the “Skramz” of Majority Rule and Pg.99, more traditional modes of popular music are used, relying on audience memory and knowledge of lyrics. This affective entrainement is a fairly valuable method for audience engagement, and yet as far as I am aware of its modes of action and reaction is rarely brought up as much more than a compositional anecdote even if it (foot-tapping, head bopping, brain-tickling music) is often the underlying goal. A type of affective entrainement is what I see as the primary qualities of these two and a half concerts (the second half of the Poppe show is not worth considering here), one which made me sit through the unnecessary overuse of Bongos, my general distaste of getting sweated on by everyone in a mosh pit, and the absolutely absurd temperature/humidity disaster that a crowded basement show can be.

youtube

youtube

None of these musicians have an explicit message for newcomers. Poppe’s compositional work in the concert contained no lyrics, no preface. Cap’n Jazz’s semi-intelligible neo-dada blabbering interests maybe those of us who used to watch Mitch Hedberg videos late at night. The screamed / vomited lyrics of Majority Rule and Pg.99, too, require study before being able to shout along.

Each in their own way, these musicians have carved out a niche for themselves, worth a trip for a few people (they can all count on me as at least one fan) but probably never on most people’s radar. The paradox of people who like music made with no consideration for them is worth celebrating. Liking this music and enjoying these shows is non-negligible emotional and physical work. In turn, however, being ruthlessly dedicated to the implementation of their own weirdo vision of music has resulted in an appreciation lasting over decades and multiple generations of fans outside their original circles. It means they’ve influenced the micropolitics of their immediate “scene” in worthwhile ways (MajRule/Pg.99 raised $36,000 for various local non-profits on that tour, Cap’n Jazz always reminds me of what’s important, etc.), and effectively managed aspirations to affect the macropolitics of scenes in general. They’ve, perhaps unintentionally, understood that this work starts by making and sharing work on a personal level and letting that work speak for itself. A few days ago, Ben Tausig, music faculty at SUNY Stony Brook (same department as internet legend Margaret Schedel) tweeted this:

Yet music’s arguably weak potency as an actant is pervasive. That is, few people’s lives are changed by music in explicitly recognizable ways, but music permeates the everyday of most people’s lives. Not many people might feel a rush of adrenaline from watching the pit throw people everywhere at a show, or that listening to Poppe for 70-90 minute is thoroughly enjoyable, but I felt it and it was strong enough that I went through the effort of writing a few hundred words about it. The Pg.99 tour made someone write Let’s make punk a threat again in a local DC paper - it probably won’t happen, but the 300 people who were at each show probably know why someone would say that and intimately relate to the implications.

0 notes

Text

Listening #2: on violent human/computer/nature interactions

Ryoji Ikeda - 0 C (1998, Touch records)

Ikeda (born 1966) is interested in machines. Recordings of the human voice return a couple of times in these tracks, and the track c7: continuum builds around what might be a heartbeat; but on this record he is mostly working from the sounds of clicks, skips, bursts, drones and impulses. Processing is secondary to arrangement and dynamics, with two major sound classes emerging: drawn out textures, and rhythmic events. The magic is in their interaction, how the absence of one emphasizes the ruthlessness of the other, how a high frequency squeal makes you long for, of all things, the click of jack being plugged in or the low thump of a heartbeat.

The first set of pieces, pre-fixed C1 through C0, show you what Ikeda can do with this barren set of sounds: never dull, never quite giving you what you expect. By the time you get to the closing track, Zero Degreees (3) and its brutally minimal techno beat sounds like it would top the pop charts.

Alvin Lucier - Sferics (1988, Lovely Music 1017)

Short for atmospherics, Lucier (born 1931) presents to us the electromagnetic utterances of the earth’s atmosphere. Sferics, in its sub-9 minute glory, appears to be the raw output of antennas aimed at picking up the stray fields from our ionosphere.

(from http://www.desertunit.org/deserting-the-site/performance-alvin-luciers-sferics/)

I find the crackle and pop of our “natural” electric environment to be increasingly relevant today - Douglas Kahn wrote most of Earth Sound, Earth Signal (MIT Press, 2013) about it. As human use of the radio spectrum becomes denser and more efficiently used because of digital multiplexing, There is something relaxing about knowing that some of the airwaves are just popping and fizzing along, not caring at all of what we might be doing to the lower strata of the atmosphere. That you can tune into this with some strange looking wood and wire contraptions is something that seems underappreciated.

Conversely, there is compositional capital to be found in having designed, assembled, refined and performed technological systems as the focus of a sonic work. More specifically, that a raw recording of a machine justifies both a listening and the machine itself is an accomplishment, with legitimacy grounded in both engineering and sound. To borrow language from economics, there is value created from transferring knowledge from a technical domain an applying it in creative one. Lucier, working in his classic position as the musician of the electronic age, presents here a physical phenomena through his usual medium of electrons and sound. Just like his classics I am Sitting In a Room or Vespers, you learn about him, about what is around him, and about the technology that connects you to them through listening. There has not been enough credit given to recordings as wordless science lessons, and to science lessons as art.

Steve Reich - Pulse Music (never recorded, performed 1969)

http://www.allmusic.com/composition/pulse-music-for-phase-shifting-pulse-gate-mc0002501034

Reich (born 1936) and his Pulse Music (for phase shifting pulse gates) is a work I’ll probably never hear. It, and the underlying technology, is effectively what pushed Reich away from the mostly-electronic works of Come Out and It’s Gonna Rain and into the acoustic works inspired by electric processes he is getting performed and known for today.

A collaboration with engineers from Bell Labs, this piece is arguably Reich’s work most dependent on electronics. Reflecting on his two performances:

... the “perfection” of rhythmic execution of the gate (or any electronic sequencer or rhythmic device) was stiff and unmusical. In any music that depends on a steady pulse, as my music does, it is actually tiny micro-variations of that pulse created by human beings, playing instruments or singing, that gives life to the music. Last, the experience of performing by simply twisting dials instead of using my hands and body to actively create the music was not satisfying. All in all, I felt that the basic musical ideas underlying the gate were sound, but that they were not properly realized in an electronic device.

Reich, Steve. Writings on music, 1965-2000. Oxford University Press, 2002. p. 44

It’s easy to imagine Reich, faced with a mess of cables and devices that would make David Tudor proud, decide that this system might not be for him.

Yet to me, this basically non-existent work constitutes the crux of Reich’s work as an experimental composer. He has rarely come so close to the synthesis of human-scale phase difference (that is, phase differences resulting from musicians working at slightly different tempos, but operating at human times scales, favored in pieces made after Pulse Music) and electronics-scale phase differences, which is a complex value relating to the frequency of the signal, usually consisting of thousandths of a second-delays and which can only be detected by humans as a varying timbre when contrasted with a signal of fixed phase through the destructive and constructive interferences that result from these two signals overlapping (the classic “woosh” sound of a phaser guitar pedal). Before him, no one had really come so close to making those two phenomena - one mostly relevant to engineers, the other mostly to musicians - work together. In never really liking what came of this, Reich picked his camp, contemporary electronic musicians came to understand phase as mostly his post-pulse music conception of it, and audio engineers continue to be confused by the vagueness with which this term is used in the context of avant-garde concerts: “phase? as in degrees of phase difference?”

Yet electronic phase - present in Reich’s early tape works, the performance work of Nic Collins, Alvin Lucier and many others, continues to fascinate musicians with circuit inclinations. It’s often there, either unintentionally implemented by circuit benders or as an early assignment for those figuring out the mechanics of digital filter design (in which phase issues become almost as important as linear responses) - one could write a decent history of experimental electronic music through a history of uses and misuse of phase in either of its conceptions.

The technological and cultural politics of Reich’s early career still deserve to be unpacked: they are clearly related. After reneging on electronic experiments of that scale with Pulse Music, Reich wrote a short piece predicting some potential futures of modern music, in which he states:

“Electronic music as such will gradually die and be absorbed into the ongoing music of people singing and playing instruments.”

immediately followed by:

“ Non-Western music in general and African, Indonesian, and Indian music in particular will serve as new structural models for Western musicians. Not as new models of sound. (That’s the old exoticism trip.) Those of us who love the sounds will hopefully just go and learn how to play these musics. ”

This is a man who in Come Out and It’s Gonna Rain had used audio recordings of minorities. Arguably, he had done so as part of an effort to reflect and amplify the racial and political conflicts of the 1960′s (as a benefit for the Harlem Six and in response to the Cuban Missile Crisis, respectively) but his work as a white artist working from audio recordings of black men seems to deserve a more pointed address than that made in those Optimistic Predictions (1970). Even more than that, his addressing of the undertones of appropriation in the second quote above seems somewhat vague. How is using non-Western musics as a structural template rather than sonic template less exoticizing, exactly?

By reneging on addressing phase technologically and instead falling back on a hyper-referential practice of patterns which extend the complex polyrhythms of non-Western musics, Reich isn’t simply making a technological choice due to convenience. He is making a culturally charged decision, one I believe he never fully addressed when he was clearly willing to write and find a platform for his writing. He regularly acknowledges the individual concepts as being adapted from another tradition, or referenced in his work, but if you know of any writing commenting on the ethics of his multiculturally-inspired practice, please do let me know.

http://www.allmusic.com/composition/pulse-music-for-phase-shifting-pulse-gate-mc0002501034

http://www.allmusic.com/composition/its-gonna-rain-for-tape-mc0002360349

http://www.keepmywords.com/2010/02/13/when-it-rains-it-pours-%E2%80%9Cit%E2%80%99s-gonna-rain%E2%80%9D/