A look at the blurred line between fiction and reality by Leanna Sveen

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Fiction and Reality

In 1886 Robert Louis Stevenson published The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. The novel is about both the light and dark sides of life as portrayed in the character of Dr. Henry Jekyll whose repressed and darker nature manifests itself in the form of Mr. Hyde. Dr. Jekyll takes a drug that transforms himself between his two characters—his respectable and good-natured side by day to his evil and murderous side by night. In 1888 actor Richard Mansfield played both characters on the London stage. According to author Judith Flanders, Mansfield skillfully acted out the drug altering change in front of large audiences. He stooped in posture and changed his gait and body language to act as Hyde. Apparently, his acting was so convincingly terrifying that women were said to have fainted in the audience and men were afraid to walk the streets of London at night.

Three weeks after the show, the first victim of Jack the Ripper was murdered (Flanders). The division within the Metropolitan Police that investigated the murder were unable to determine much about the murderer’s identity. As time went on, investigations continued to no effect while more people were killed and horribly mutilated. The people of the East End were understandably shaken.

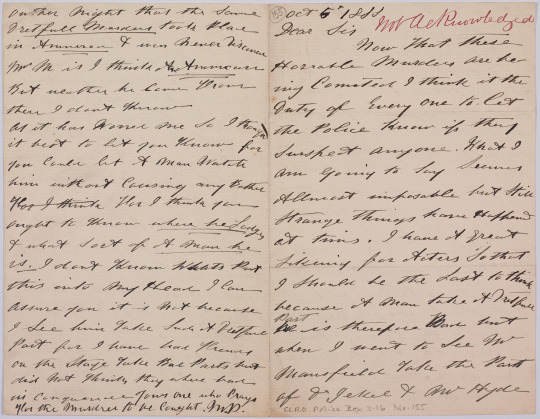

According to author Greg Buzwell, many linked the remarkable coincidences between Jekyll’s respectability by day and Hyde’s murderous nature by night to that of the mystery surrounding Jack the Ripper. With Jack’s true identity unknown, the story of Jekyll and Hyde may have sparked the fear that Jack too might blend in to the common crowd by day, walking among people in the streets of London, completely undetectable as a murderer (Buzwell). What’s more, they were disturbed by the possibility that Jack the Ripper might also have been a man they knew and respected who somehow concealed a murderous secret. This notion may have been new to the people of an age that believed everything could be known, named, and understood. An anonymous letter was even sent to Scottland Yard around this time accusing Mansfield himself of being Jack the Ripper. The letter says, “I should be the Last to think because A man take A dretfull Part he is therefore Bad but when I went to See Mr Mansfield Take the Part of Dr Jekel and Mr Hyde I felt at once that he was the Man Wanted … I do not think there is A man Living So well able to disgise Himself in A moment …” (Flanders). It remains unclear however, whether the police ever actually took the accusation seriously and investigated Mansfield or considered him a possible suspect.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Physical Appearance and Criminality

The fear that Mansfield’s terror on stage could not simply be due to exceptional acting may have been related to ideas growing in popularity about criminality in the 1900s. According to Buzwell, criminologist Cesare Lombroso thought “criminal behaviour was a throwback to earlier evolutionary states of humanity, and could be detected in advance through study of the shape of the individual’s skull”. Many scholars believe that Stevenson had been inspired by Lombroso when he wrote Jekyll and Hyde. Author Stephan Karschay sees Lomrboso’s ideas reflected in Hyde’s behavior. He says, “Hyde’s perverted mutilation of the body of Sir Danvers can thus be read as the gruesome result of the degenerate’s ‘irresistible craving for evil for its own sake’, an inclination Lombroso considered one of the many inborn qualities of the degenerate criminal” (91). While much of physical criminality theory focused on head formations, other parts of the body were also considered supporting evidence such as having thinning body hair, dark skin, or jug ears. Lombroso believed that these and many other attributes were common among savages, criminals, and races that were not white (Karschay, 47). These physical attributes were paired with “lack of moral sense, revulsion for work, absence of remorse, lack of foresight…, vanity, superstitiousness, self-importance, and, finally, an underdeveloped concept of divinity and morality” (Karschay, 47).

However, Lombroso was not the first to think that physical appearance reflected what lies beneath. Physicist Franz Joseph Gall theorized that different protrusions and intrusions at different locations of the skull represent the development of specific character traits. He reasoned that the brain was an organ that grows in size as it develops and that the skull adapts to the shape and size of the brain. So, having a large head would thought to have have been a good thing as it would theoretically carry a large and well developed brain. I wonder if this is why artist John Tenniel’s depiction of Lewis Carroll’s Queen of Hearts shows her with a large head—representational of her power, yet her sloping forehead may be indicative of her cruelty. Is it uncertain whether this interpretation was intentional or not. Carroll did visit a phrenologist at one point in his life though, so I think it is safe to wonder at this possibility (Ford, Cameron, 47).

Gall’s theory became known as phrenology as he toured across Europe, lecturing on it as early as 1805 and was met with initial success. However, over the years, phrenology was repeatedly challenged and inconsistencies in evidence started cropping up. It was not until the 1850′s that the science behind the theory was finally discredited but phrenology did not disappear altogether (Van Whye). Instead, it was adopted by amateurs looking to market the theory by claiming to be able to see the strengths and weaknesses of an individual’s character based on head shape. Although phrenology had morphed into a pseudo-science over time, the idea that physical appearance somehow revealed the person within stuck as a real possibility in the minds of the public. This popular concept may explain why some had a difficult time in believing that Mansfield could simply be a skilled actor and not a killer himself. After all, Mansfield had obviously looked and behaved wickedly enough on stage to have contrived such terrified reactions.

“When the archvillain, Moriarity, meets his adversary Sherlock Holmes for the first time, Moriarity's immediate comment was, ‘You have less frontal development than I should have expected’” (Wohl, Van Whye).

0 notes

Text

Darwin

Charles Darwin’s The Descent of Man came out in 1871, 15 years before The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. The book explains that humans evolved from ape-like specimen over time through survival of the fittest and, prior to the book’s publication, Darwin had feared the reception of his ideas by the overwhelmingly religious public. While the common belief of the time was that humans were a special creation by God, Darwin’s ideas reduced humans to just another species within the animal kingdom. However, his ideas were generally well received and quickly influenced public opinion. Buzwell says that “for many, the balance between ‘faith’ and ‘doubt’ had tipped disturbingly in favour of the latter, and questions about the origins, nature and destiny of humankind had become matters for science, rather than theology to address.”

The ideas originated in this book and those birthed in the aftermath had also influenced Stevenson’s writing in Jekyll and Hyde. For instance, Jekyll is a doctor who looks to science for a solution to the duality of his nature. His lesser side, Mr. Hyde, is described as hairy, dwarfish, ape-like, and having “something wrong with his appearance; something displeasing; something down-right detestable” (Stevenson, 10-11). He is additionally described by many characters as having a deformity somewhere, yet none can make out where exactly it is. Hyde is ruled by animalistic impulses and represents an earlier form of human evolution, as previously mentioned in his relation to Lombroso’s idea of the degenerate criminal. Thus, Jekyll’s duality indicates that human nature can embody love, kindness, and empathy alongside malice, cruelty, and neglect. The dark side of Jekyll is the one that he must hide because the discovery of it by others would ruin his reputation in society, which would condemn his first and foremost identity of self.

In response to the duality discussion of the age, a general sense of dread and uncertainty about humankind was felt among Victorians (Burdett). If there is a divine purpose for mankind, then these negative aspects of human life can be overshadowed by the promise of better things to come. However, when human nature is viewed as an accident or a random outcome of chance then the unanswered question remains about what humankind truly is, if not a highly evolved pack of apes, and what we then might become. If species were guaranteed to always weed out the negative qualities overtime, then there would be less reason to worry. However, survival of the fittest does not guarantee that the strongest survival qualities are desirable ones. For instance, a meeker and kinder nature is less likely to make it in the world than a brutish confident one. Yet, if given the choice, many would likely agree that the former is preferable to the latter. These possibilities ignited the idea of eugenics—the betterment of future generations through controlled reproduction (Burdett). One popular idea of how to implement this control was the encouragement of producing “well-bred offspring” and discouragement toward those who have “underdeveloped traits” from having any offspring. Many believed that the poor and foreigners were those with undesirable traits. They were thought generally to be simple-minded and born criminals while the white middle class allegedly had the desirable traits (Burdett). This sort of stereotyping appears to have derived again from the desire to name a thing, understand it, and thus fear it less.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Understanding the Reception of Jekyll and Hyde in the Theatre

A trend was occurring during the 19th century:

“Works such as Robert Louis Stevenson’s Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886); Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891); Arthur Machen’s ‘The Great God Pan’ (1894); H G Wells’ The Time Machine (1895) and Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897) all explore the theme of the human mind and body changing and developing, mutating, corrupting and decaying, and all do so in response to evolutionary, social and medical theories that were emerging at the time” (Buzwell).

Stevenson’s character Dr. Jekyll reflects some concerns of the time (two examples being his faith in science to solve mankind’s problems and the relationship between character and physical appearance). Yet, his complex duality was a shocking contrast to many of the ideas that Victorians were trying to wrap their heads around.

To understand the audience’s reaction to Mansfield performance, we must understand the characters Jekyll and Hyde. Jekyll is first and foremost a good man. Yet, from an early age he identified deviant and sinister urges within himself that he hid from society but explored in secret. He discovered how to separate the good side of himself from the bad by taking a drug that would change him from the man he had become—the reputable Dr. Jekyll—to his evil alter ego Mr. Hyde. The change would not only alter his character, but his appearance as well. In the novel, Jekyll is described in a scene with his friend and lawyer Mr. Utterson, who is also an upright and honest character. Jekyll is “a large, well-made, smooth-faced man of fifty, with something of a slyish cast perhaps, but every mark of capacity and kindness — you could see by his looks that he cherished for Mr. Utterson a sincere and warm affection” (Stevenson, 21). This description of Dr. Jekyll shows that his inward character is reflected in his outward appearance, which, by Victorian assumptions of the time, is consistent with popular beliefs.

And yet, the murderous Hyde resides buried within the heart and soul of Dr. Jekyll. None of the other characters in the novel had even hinted at detecting anything detestable about Jekyll. To the Victorian readership or audience, who were coming to believe in the physical presence of character, the idea that a monster lurks beneath the surface of an attractive man, who is held in high regard by all, was very disturbing. Therefore, it is possible that it is not the murderous Hyde that audiences and readers found so unnerving—but the respectable Dr. Jekyll. Author Charles Dickens took an interest in physical appearance and character as well. In regards to a real doctor and murderer named William Palmer, “Dickens saw a face conveying ‘nothing but cruelty, covetousness, calculation…and low wickedness’. He liked, he said, a murderer who looked like a murderer” (Flanders). Jekyll’s duality, however, presented a contradictory idea—that darkness might not actually be manifested physically, rather it might be present within anyone, undetected and concealed. This is presumably the idea that most alarmed readers and audiences about the story because if it is true, then seeing and knowing the evil within others might be difficult or near impossible. However, seeing Mansfield as Hyde—stooped, walking irregularly, and acting menacingly—may have confirmed to others (who stuck to their beliefs in the link between physical appearance and character) the idea that evil must physically reveal itself in some way. If the connection was being drawn between Jekyll and Hyde and Jack the Ripper, then it is no wonder people were terrified after seeing an actor transform from good to evil and back again—likely considering that Jack was capable of a similar altercation that involved skilled acting toward the watchful eye of society.

“man is not truly one, but truly two" (Stevenson, 62).

1 note

·

View note

Text

Research Experience and Points of Interest:

I was initially interested simply in the dual nature of Jekyll and Hyde and the book’s reception in Victorian audiences. I told Dr. Cook of my interest and she provided me with two articles from the British Library, suggesting that I consider researching Victorian knowledge of criminality as well. I started with the two articles, which I found richly useful for this project, and began searching for more information on my topic within the British Library. All the while I was looking for a specific event or illustration to plant my focus. That’s when I found the letter that had been sent in to the H division police department accusing Mansfield of being Jack the Ripper. I read on that the media was referring to Jekyll and Hyde as Jack as well, and I was hooked on the topic from there. I wanted to know what it was that made people so afraid of Jekyll and Hyde to the point that the fiction was becoming blurred into reality. Assuming the letter was not intended to be a hoax, I wanted to understand how an actor could be accused of committing real murders because he played the role of a murderer too well. I began my research (with a vague idea of where to take it) around the half way mark through the semester. I also watched the Ripper Street series (currently on Netfix) that is actually a fairly credible source for research, and it really helped me to contextualize the role of the police force in the lower class slums of London. The show also touches on the degenerate criminal, stereotypes of class and race, Darwin in Victorian culture, and the theatre—all of which I found very interesting and some of which proved relevant to my research.

In class, we had been discussing how The Descent of Man had changed many popular opinions shortly after its publication. People were fearful about the future of humanity and related ideas were being explored in the fiction of the time. So, I was also looking for articles on Darwin in relation to Victorian culture. One of the articles I had been pouring over mentioned phrenology and physiognomy, which seemed relevant to Lombroso’s ideas about criminals. Looking into it, I found a useful page from the Victorian Web explaining the history of phrenology and its large impact on society and more particularly on criminology (regardless of eventually becoming a pseudo-science). I guess I can mention here that I fell down a rabbit hole reading tons of different articles and sections (mostly on topic) from the Victorian Web and the British Library. I found them both very easy to navigate and the information rich. From there I realized that I had at some point found a possible explanation for the very odd accusation placed on Mansfield. I do not claim to know the reason Mansfield was accused (as this information is not downright stated by a reputable source anywhere I could find despite intensive searching) but I feel better able to understand the real fears of the people regarding Jack the Ripper and Jekyll and Hyde in their historical contexts. Both Jekyll’s and Hyde’s physical appearances would have been very revealing to Victorian audiences, who would have expected to see the physical traces of goodness in Jekyll and the wickedness in Hyde even though Stevenson presents a contradiction to this popular concept in the evil that is undetectable in Jekyll. I think it is possible that the audiences watching Hyde being acted out on the stage might have had a hard time accepting that Mansfield was really just acting because their beliefs may have influenced them to reason that they were looking evil in the face. Not that horror was anything new to behold on stage, as it has been a part of the theatre for centuries, but the idea that inner evil presents itself outward in physical appearance was a new idea to the 19th century and was well believed by the time Mansfield took the stage.

What did I learn from my research about popular culture in the 19th century? Well, I found it really interesting that phrenology was eventually devalued as a real science and yet it still held in popularity for a good half of a century. It seems that fear sometimes works harder and longer in the mind than reason does. I think this might be why an audience member could have looked at the Hyde on stage and saw a murderer and also why people had a hard time disbelieving that they could see exactly who the degenerates are and what it is that makes them born criminals.

0 notes

Text

References

Burdett, Carolyn. "Post Darwin: social Darwinism, degeneration, eugenics." The British Library. The British Library, 19 Feb. 2014. Web. 15 Apr. 2017. <https://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/post-darwin-social-darwinism-degeneration-eugenics>.

Buzwell, Greg. “Actor Richard Mansfield in a stage adaptation of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde.” Digital image. The British Library. N.p., n.d. Web. <http://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/duality-in-robert-louis-stevensons-strange-case-of-dr-jekyll-and-mr-hyde>.

Buzwell, Greg. "Gothic fiction in the Victorian fin de siècle: mutating bodies and disturbed minds." The British Library. 26 Sept. 2014. Web. 08 Apr. 2017. <http://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/gothic-fiction-in-the-victorian-fin-de-siecle>.

Buzwell, Greg. "'Man is not truly one, but truly two': duality in Robert Louis Stevenson's Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde." The British Library. N.p., 13 Feb. 2014. Web. 20 Apr. 2017. <http://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/duality-in-robert-louis-stevensons-strange-case-of-dr-jekyll-and-mr-hyde>.

Flanders, Judith. “Anonymous letter to City of London Police about Jack the Ripper.” Digital image. The British Library. N.p., n.d. Web. <http://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/jack-the-ripper>.

Flanders, Judith. "Jack the Ripper." The British Library. 07 Mar. 2014. Web. 15 Apr. 2017. <http://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/jack-the-ripper>.

Ford, Colin and Julia Margaret Cameron. Julia Margaret Cameron : A Critical Biography. Los Angeles : J. Paul Getty Museum, 2003., 2003. EBSCOhost, ezproxy.lib.usf.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.lib.usf.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cat00847a&AN=usflc.020042814&site=eds-live.

Hulme Beaman, S G. Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. Digital image. The British Library. N.p., 1930. Web. <https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/illustrations-to-strange-case-of-dr-jekyll-and-mr-hyde-1930>.

Karschay, S.. Degeneration, Normativity and the Gothic at the Fin de Siècle, edited by S. Karschay, Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2015. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/usf/detail.action?docID=1953025.

Perkins, George B., et al. "Mansfield, Richard (1854-1907)." Benet's Reader's Encyclopedia of American Literature, vol. 1, HarperCollins, 1991, p. 679. Literature Resource Center, go.galegroup.com/ps/i.do?p=LitRC&sw=w&u=tamp44898&v=2.1&id=GALE%7CA16852415&it=r&asid=0e8d9f3805cf9fed162f9f4acb54422e. Accessed 21 Apr. 2017.

“Richard Mansfield in the role of Jekyll and Hyde.” The British Library. 10 Apr. 2014. Web. 15 Apr. 2017. <https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/richard-mansfield-in-the-role-of-jekyll-and-hyde>.

S. Wohl, Anthony, and John Van Whye. “Phrenology and Race in Nineteenth-Century Britain.” The Victorian Web. N.p., 1 Nov. 2004. Web. 15 Apr. 2017. <http://www.victorianweb.org/science/phrenology/rc3.htm>.

Stevenson, Robert L. The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde: and selected short fiction. New York, NY.: Barnes and Noble , 2003. Print.

Tenniel, John. “Off with her head!”Digital image. The Victorian Web. N.p., 21 Oct. 2007. Web. 23 Apr. 2017. <http://www.victorianweb.org/art/illustration/tenniel/alice/8.2.html>.

Van Whye, John. "The History of Phrenology." The Victorian Web. N.p., 2000. Web. 15 Apr. 2017. <http://www.victorianweb.org/science/phrenology/intro.html>.

0 notes