Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

The Unspoken Weight of Love: Unraveling Memory and Grief in Aftersun

What’s so haunting about Aftersun is how it portrays the relationship between Calum and Sophie as both intimate and unknowable. Calum is so deeply present in Sophie’s life during their vacation—listening to her, encouraging her independence, and showing her endless love. Yet, he’s simultaneously slipping away, weighed down by something she cannot see. His love for Sophie is palpable, but it’s also tethered to an immense sadness, a sense that he believes he’s failing her or that he’s not enough. That tension—between his love and his private pain—permeates the entire film and makes every small interaction feel loaded with unspoken emotion.

The way Aftersun presents memory is devastating in itself. It’s not linear; it’s fragmented, hazy, and colored by adult Sophie’s retrospective grief. The use of the camcorder, for instance, adds a layer of artificiality to these cherished moments, reminding us that even our most vivid memories are imperfect recreations. Adult Sophie isn’t just remembering her father—she’s interrogating those memories, trying to reconcile the happy, carefree image of him from her childhood with the quieter, darker truths she now understands. This dissonance captures the universal ache of realizing, too late, the depth of someone’s struggles.

Calum’s attempts to shield Sophie from his pain are almost unbearable to watch. There’s a scene where he dances or smiles, but there’s a weight behind it—a forced lightness that feels more like desperation than joy. It’s as though he’s holding back an emotional flood, trying to give Sophie something pure and untarnished while knowing he’s barely holding it together. This dynamic is tragically familiar to anyone who’s seen a loved one try to carry their pain in silence.

The film also quietly explores the idea of legacy—not in the grand sense of achievements, but in the subtle ways we leave pieces of ourselves behind in others. Sophie carries Calum’s warmth, his curiosity, and his love, but she also carries his absence. That absence—the unanswered questions, the things left unsaid—shapes her adult life just as much as his presence once did. It’s heartbreaking to think that Calum, in his quiet despair, might have believed he was failing as a father, while Sophie remembers him as the most important person in her world.

What really lingers is the way Aftersun handles grief—not as something loud or dramatic, but as a quiet, enduring ache. The moments of joy during their vacation feel fragile, like they’re suspended in time, but they’re forever shadowed by the knowledge of what comes later. The film doesn’t give us neat answers about what happened to Calum; instead, it leaves us with Sophie’s unanswered questions, her longing to understand a father who kept so much of himself hidden.

And that ending—it’s so haunting because it refuses to resolve the tension. The final scenes, where Calum fades away, feel like a metaphor for how grief works: you’re left with fragments of memory, images and feelings you can’t quite grasp fully. The open-endedness isn’t just about Calum’s fate; it’s about the impossibility of truly knowing someone. Even the people we love most, the ones we think we understand, carry parts of themselves that remain forever out of reach.

Aftersun is about those parts—the silences, the private battles, the emotional terrain we never get to see. It’s a testament to how much we miss in the moment and how, years later, we try to piece together the truth through the fractured lens of memory. It’s a profoundly human story, one that captures the beauty, fragility, and tragedy of loving someone who is both deeply present and painfully distant.

youtube

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Manhattan, New York City, during the blizzard of January 1996

8K notes

·

View notes

Text

A Personal Reflection on Guilt and Repression

James Sunderland’s story in Silent Hill 2… I can’t help but see a bit of myself in that. The way he’s drowning in his own guilt, unable to face the truth—it feels familiar. I haven’t gone through anything as extreme as he has, but that feeling of burying pain, of repressing emotions because they’re just too hard to deal with… I’ve been there. It’s like, sometimes it’s easier to pretend things didn’t happen, to numb yourself, because facing it head-on feels like it would destroy you.

James killed Mary in this moment of desperation, but it wasn’t out of pure malice—it was exhaustion, grief, maybe even love twisted by too much pain. I can understand that—how, when you’re worn down to your core, you do things you regret, things that stay with you. And just like him, I’ve had moments where I didn’t want to face what I’d done, or how I felt, so I pushed it away, hoping it would stay buried. But it doesn’t. Just like James, the more you try to ignore it, the more it festers. That guilt, that pain, it finds a way to surface, sometimes in ways you don’t expect. The way he was haunted by monsters—my version of that might not be so literal, but it’s the same idea. The longer I run from my own feelings, the more they twist and distort until I can’t escape them.

James’s mental state in Silent Hill 2 is a mirror of how unresolved trauma and guilt can take control. His dissociative amnesia is his mind’s way of protecting itself—he can’t face what he’s done, so he convinces himself that Mary died of her illness. It’s like his brain has this wall, trying to keep the truth from breaking him. But his repression doesn’t make the pain go away; instead, it shows up in other ways. The whole town of Silent Hill becomes this reflection of his inner world, full of distorted, terrifying versions of the things he’s trying to bury.

And then there’s Pyramid Head—this manifestation of his desire to punish himself. It’s not just a random monster; it’s the part of James that knows he’s guilty, the part that believes he deserves to suffer for what he did. It’s like every time he tries to move forward, his mind forces him to confront that guilt. The same way I can’t shake the feelings I try to suppress, James is haunted by his own mind, constantly dragged back to the truth he doesn’t want to face.

His emotional numbness and depression feel familiar, too. He’s going through the motions, almost like he’s disconnected from the world, unable to really feel anything because he’s so overwhelmed. I’ve had those moments, too, where you’re so buried in your own head that you can’t feel anything but this dull, empty ache.

And it’s not just James—it’s me, too. I guess, like him, I’ve got this internal struggle going on—denial versus acceptance. I can keep running, keep numbing myself, but deep down, I know I’ll have to confront it eventually. It’s just… how do you face something so painful without it breaking you? And when you finally do face it, will it destroy you, or will it set you free? That’s the real question, isn’t it?

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

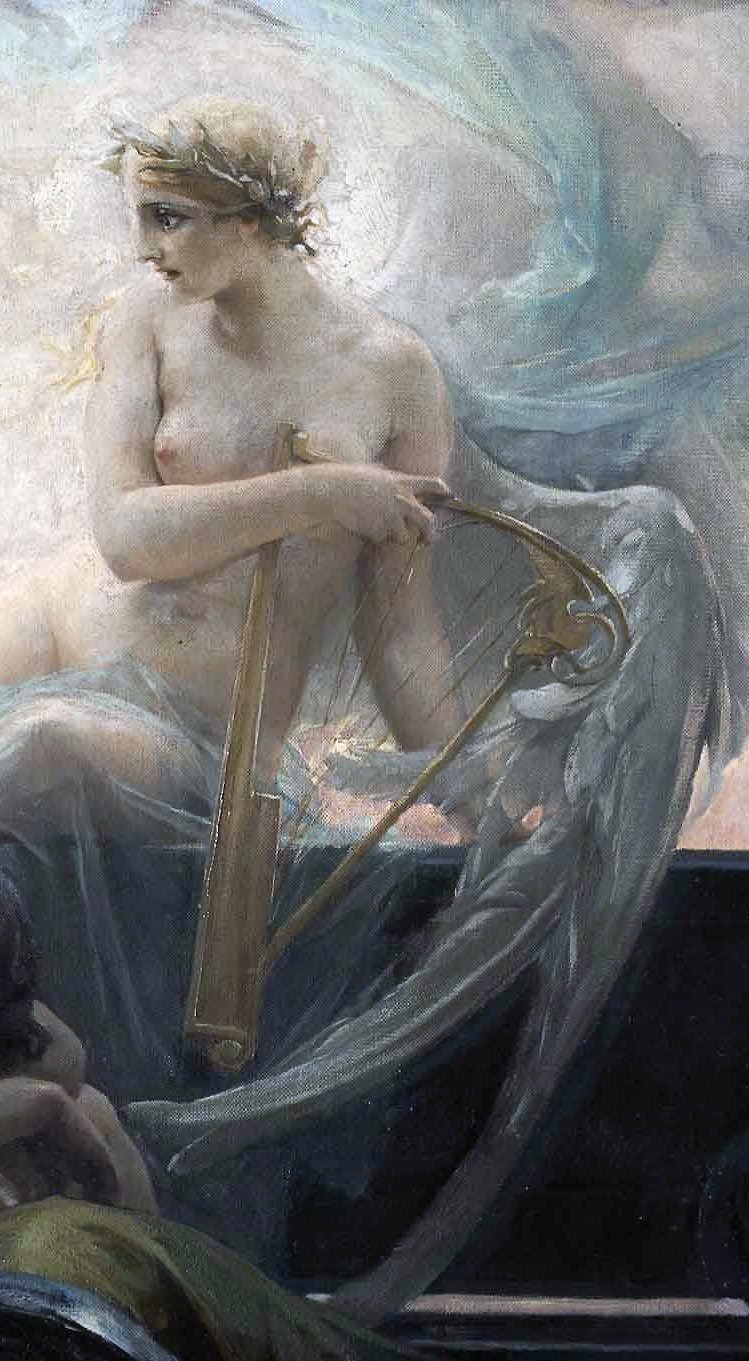

The End of All Things (1887)

— by Maximilian Pirner

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Giacomo Grosso (1860-1938, Italian) ~ Sorpresa, 1926

4K notes

·

View notes