| Humayra Rawat | 21 | Occupational Therapist | Avenger

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Hamba Kahle!

4 little green seedlings were sown into the rich soils of the Clermont-KwaDabeka townships hoping to grow and mature into something beautiful. Community health workers tended to these budding plants, rooting them deep into the townships whilst community residents showered them with love and acceptance not knowing that they would reap the benefits later. After 6 weeks, the plants came to fruition, giving back to the nourishing community that enabled them to grow. And although the 4 seedlings had to be relocated from the township, they continue to survive and flourish because of the resilience passed on to them from their place of growth. Hamba kahle Clermont-KwaDabeka!

Reflecting over this block I realize how much I’ve grown professionally especially in terms of understanding my roles as an occupational therapist working in a South African context. I learnt that one of our most important roles is that of advocacy. According to the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework, advocacy is defined as the “efforts directed toward promoting occupational justice and empowering clients to seek and obtain resources to fully participate in daily life occupations. (AOTA, 2014 as cited in Stover, 2016). At its core, advocacy is demonstrating concern for a person’s well-being by assisting in the pursuit of that person’s cause. There are many different types and approaches to advocacy

As occupational therapists, we naturally pursue individual advocacy when treating home visit or clinic-based clients. We aim to empower people to advocate for themselves by teaching them the skills needed to do so. A simple way of how OT’s can help individuals with disability become self-advocates includes teaching them how to relate their needs to their medical team to ensure better treatment. Encouraging one of my home visit clients to ask questions to her doctors regarding her medication and surgery options is a simple example of encouraging her to become a self-advocate.

Community advocacy is a larger version of individual advocacy. The difference is, community advocacy involves groups of people acting to affect positive change (How to be an Advocate for Yourself & Others, 2017). A grassroots approach can be used in this type of advocacy whereby communities themselves identify issues and hope to rectify these mistakes. For example, in the Clermont-KwaDabeka community, residents identified substance abuse, teenage pregnancies and HIV as major problems within the community. Thus, there are substance abuse awareness campaigns and women empowerment programmes such as “She Conquers” that are run by community members. As occupational therapist, we joined some of these advocacy programmes to advocate and promote better occupational choices amongst the youth.

A top down approach can also be used in community advocacy. A top down model emphasises the identification of needs or goals by individuals outside of the community (Loue, 2006). As occupational therapists entering the community we identified the high rate of developmental delays amongst children in schools as one of the issues facing the community. That coupled with the fact that there is only one occupational therapist available to the whole Pinetown district means that these children are unable to receive the help that they require. Thus, previous OT students started a petition for more occupational therapist to be employed to the surrounding schools as this would combat the problem. Simply collecting signatures for this petition is then an act of advocacy.

As occupational therapists we also belong to the community of rehabilitative therapists. Our profession is often unheard of and many people in the Clermont-KwaDabeka community are unaware of our services and its benefits. Thus, creating awareness of our profession and other rehab professions can also be seen as an act of advocacy; professional advocacy. Conducting awareness days, providing free screenings, conducting talks at the clinic and even handing our pamphlets all aimed at advocating for OT. Another way that we advocate for our profession and perhaps the most important way, it proving our reliability and value to our clients such that they feel the need to share stories about work in the community. Thus, we should always consider ourselves as ambassadors of our profession.

After completing this block, I feel prepared and much more excited about the prospect of community service next year. At the same time, I realize how different the experience will be; whilst community practice in general is unstructured, this module still offered some structure in that there were already projects formed, already relationships built within the community, already a contact list formulated and there was a handover to explain and guide students practice. In stark contrast, there will be none of this available to us when we begin community service. Thus, I realize how much more effort will be required next year when serving in a completely new community. And whilst the thought is scary, it is also exciting. One could look at it as a blank page, a clean slate to truly assess our performance as community practitioners.

OT out!

REFERENCES:

Stover, AD. (2016). Client-Centered Advocacy: Every Occupational Therapy Practitioner's Responsibility to Understand Medical Necessity. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 70(5)

How to Be an Advocate for Yourself and Others. (2017). Retrieved from: http://www.thewellproject.org/hiv-information/how-be-advocate-yourself-and-others#Community%20Advocacy

Loue, S. (2006). Community Health Advocacy. Epidemiol Community Health 60:458–463.

Gould, T., Flemming, M.L.,Parker, E. Advocacy for health; revisiting the role of health promotion. Health Promotion Journal of Austrailia. 23(3)

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jack of All Trades

‘A jack of all trades’ they say. Occupational therapists are often seen as having many roles to play, many responsibilities to fulfill and many skills to teach. Construed negatively, some might argue that we have no niche in health care, often encroaching on many professions work (Lyron,2018) whilst others, such as myself, choose to see our variable skills as an asset, an advantage because by working within such a large and expansive scope we have more to offer and a wider audience to offer it too. Perhaps one could even say that it makes us much more employable. It is only by gaining exposure to community practice and working in a primary health care center that I have truly started to understand how variable our roles really are.

According to the World Health Organisation (2018), “primary health care is based on scientifically sound and socially acceptable methods, universally accessible to individuals and families with their full participation at a cost that the community and country can afford in a spirit of self-reliance and self-determination.” Its principles are based on providing accessible, acceptable, affordable, available and equitable health care for all using a multisectoral approach and aims to shift away from a mainly curative focus to a rehabilitative, preventative and promotive one, prioritizing service delivery to those who need it most. As occupational therapists working in health, the use of the community-based rehabilitation(CBR) approach, specifically the CBR matrix, enables us to define our roles in terms of these PHC principles.

Figure 1: CBR Matrix (CREATE, 2015, p. 4)

The roles of a community OT is not specific to one domain or element of the CBR matrix. Instead we work across all 5 key elements i.e health, education, livelihood, social and empowerment elements. We aim to not only provide rehabilitative services, but also preventative and promotive care too. Thus, an OT in primary health care will see a variety of clients, abled and disabled, young and old. It is in these settings that we truly benefit from being a ‘jack of all trades’.

The rehabilitative role of occupational therapists is slightly modified within the community setting as we conduct home visits and provide therapy to individuals within their home environments rather than solely at the clinic or health center. In this way our services become more accessible to those who need it. In community we also adopt a promotive role, usually advocating for services or facilities that might enable better health for its community members. This could include advocacy for a new park, swimming pool or activity center with the aim of improving physical health and well-being. It could also include empowerment programmes for marginalized individuals and persons with disabilities. Preventative roles of an OT in PHC might include screening and early detection of disability at clinics or schools, awareness campaigns focusing on substance abuse or mental health, HIV and even TB. Thus, we work with many other service providers, community centers and facilities, using a variety of tools to achieve our rehabilitative, promotive and preventative goals.

One such tool used to achieve health promotion and prevention is the tool of media. Media helps health workers expand their audience reach, which is crucial considering the fact that face-to-face channels of communication often require too many human resources and reach only a small number of people in large, underserved rural areas (Unite For Sight,2009). The mass media provides an important link between the people and vital health information. An example of its use can be seen in the recent listeriosis outbreak. News of the disease was aired on radio and TV, written about in newspapers and shared via social media, albeit sometimes in a less serious form of memes or funny gifs. Using media outlets, individuals became aware of what listeriosis was, where it could be found, its symptoms and what precautions to take to reduce the risk of contracting the disease.

Another example of how media can be used successfully for health care promotion and prevention includes campaigns such as OneLove which ran for 3 years. Launched in January 2009, the South African Onelove campaign aimed to reduce new HIV infections in South Africa. The focus of the campaign was on multiple concurrent partnerships. The campaign aimed to shift social norms away from multiple sexual partnerships and encourage fulfilling monogamous relationships that will prevent the need for other relationships. As part of its communication strategy, the OneLove campaign used mass media, which included the Soul City television drama series, a radio drama, print materials, and advocacy to achieve its aims.

“The results of the campaign revealed that it had reached an estimated 61% of the adult target population, within the first five months of the launch. Soul City 9 TV, which carried strong onelove and HIV prevention messaging, reached 51% of the population and was the second highest performing programme in terms of viewership for the three months that it aired. In the first 18 months of the campaign, over 16 000 adults attended onelove HIV community-based training nationally, and over 4 000 people attended 55 community dialogues. Some 91 newspaper articles and 37 magazine articles addressing onelove were published. (Letsela & Weiner, 2012)”. These results show the rates of success associated with media and health promotion strategies.

In Clermont-KwaDabeka, the use of social media platforms such as twitter, facebook and Instagram are used by facilities such as the youth center to promote upcoming events, dialogues and other empowerment programmes that aim to promote women empowerment, establish opportunities for constructive activity in the community and provide opportunities for education and employment. As techno-savvy OT’s we aimed to work in collaboration with the center, gaining access to their followers on these platforms to promote our profession and services. Skits, dance videos and creation of challenges are creative methods to target the youth to promote a healthier life. Roles of actors, singers, dancers or even meme creators can therefore be added to our long list of “trades” when it comes to our profession.

All in all being a jack of all trades is never a bad thing when working in a community setting. There’s no such thing as having too many skills!

OT out!

REFERENCES:

CREATE. (2015). Understanding Community Based Rehabilitation in South Africa. Retrieved from: www.create-cbr.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/CBR-Study-Report.pd

Letsela, L and Weiner, R. (2012). OneLove Campaign in South Africa; What has been achieved so far? Retrieved from: https://www.soulcity.org.za/research/evaluations/campaigns/onelove-evaluation/onelove%20interim%20eval%20Report-final%20incl%20cover.pdf

Naidoo D, Van Wyk J, Joubert RW.(2018). Exploring the occupational therapist’s role in primary health care: Listening to voices of stakeholders. Afr J Prm Health Care Fam Med. 8(1)

Lyron, S. (2018). Honest thoughts on OT school and 5 pieces of advice for prospective students.[Blog Post] Retrieved May 4,2018 from: https://otpotential.com/blog/2014/11/22/honest-thoughts-on-ot-school-and-5-pieces-of-advice-for-prospective-students

Uniteforsight.org. (2018). Health Communication Course: Module 5 - The Role of Media in Health Promotion. Retrieved from:https://www.uniteforsight.org/health-communication-course/module5

0 notes

Text

Freedom Day?

On 27 April 1994, people of different colours, races, religions, genders and ethnicities marched in their millions to the polls, waiting in anticipation to cast their vote in South Africa’s first ever democratic election. A different sun rose on the South African horizon that day, one that symbolized hope, happiness, freedom and release from the oppressive shackles of the apartheid system. A sun that promised equality, democracy and life of a better quality where people were no longer discriminated against based on their race. “A new South Africa” they said. Yet 24 years later and 2 decades worth of unfulfilled promises and betrayal from the government, we find ourselves living in a country still riddled with injustice, inequality and a new type of discrimination. A discrimination that prioritizes the rich over the poor, the elite over the impoverished. The current situation of our country begs the question; are we really free from Apartheid?

According to the World Bank Report (2018), 55% of the population lives below the poverty line with those closest to the upper poverty line living on just R992 per person. In addition to this, 27.7% of the population is unemployed and up to 70% of homes suffer food insecurity with many of these households skipping meals (World Bank Report, 2018). The education statistics are just as bleak. A 2016 international literacy report found that eight out of 10 school pupils in Grade 4, cannot read (Jagarnath,2018). The lack of resources and equal opportunities perpetuating these conditions are connected to the political influences operating in the social and economic environment of our country.

With millions still living in townships and rural areas without proper housing, sanitation, running water or electricity (reminiscent of apartheid infrastructure), we cannot deny the failure of our government in righting the wrongs of the past. Most of the injustices in the country can be linked back to the ANC which has an astoundingly poor track record of governance. “The party is regularly charged with wholesale corruption, repression, sustaining neo-apartheid forms of rule in the countryside and the cities and the failure to redistribute land and democratise the commanding heights of the economy by removing it from the domination of white capital” (Jagarnath,2018). The lack of basic service delivery has led to many violent protests as people start to realize the lack of political will from the ANC in implementing even the most basic economic reforms for all South Africans(Conway-Smith,2014).

As student occupational therapists, we see the effects of these political constraints first-hand whilst working in communities such as Clermont-KwaDabeka in the occupational choices and occupational engagements of its people. Dropping out of school to join gangs, commit crimes or deal drugs are perceived as some of the only occupational choices that community members have, to escape the poverty and unemployment so prevalent in the country. Thus, we see how the unresponsive, collusive and exploitive policies of the government effect not only the state of the community, but also individuals and their daily occupations. We see how actions by the government aims to maintain the privileged over the impoverished, forcing people to live an unsatisfactory, undignified life. Thus, as occupational therapists growing into political beings we identify a new type of apartheid taking over South Africa. An occupational apartheid (Kronenburg,2005).

If the promise of freedom is to be restored to South Africans, the first step is to rebuild the power of the impoverished people. New formations must be created to build their power to the point where a new order can be constructed in the countryside, the cities and in the economy. Then only shall the rays of hope, happiness and freedom rise once again among all South Africans.

OT out!

REFERENCES:

Kronenburg, F and Pollar, N. (2005). Overcoming Occupational Apartheid in Kronenburg, F. Algado, S.S. Pollard, N.(Ed) Occupational Therapy Without Borders. (pp 58-85) United Kingdom, UK; Elsevier Limited.

Jagarnath, V. (2018) Why only revolutionary change will deliver real freedom. Sunday Times. Retrieved from: https://www.timeslive.co.za/politics/2018-04-27-why-only-revolutionary-change-will-deliver-real-freedom/

Conway-Smith, E. (2014). 20 years since apartheid: what’s changed in South Africa and what hasn’t. Retrieved from: https://www.pri.org/stories/2014-04-27/20-years-apartheid-whats-changed-south-africa-and-what-hasnt

World Bank Report. (2018). Overcoming poverty and inequality in South Africa; an assessment of drivers, contraints and opportunities. Retrieved from: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/530481521735906534/pdf/124521-REV-OUO-South-Africa-Poverty-and-Inequality-Assessment-Report-2018-FINAL-WEB.pdf

1 note

·

View note

Text

Braaied or Boiled?

It’s early morning and the streets of Clermont-KwaDabeka are already bustling with activity. Informal vendors have already set up shop, their vibrant coloured pyramids of fruit and vegetables taking centre stage in their make-shift wooden structures. Other vendors show off their sweet treats and salty chip delights. A glint of red packaging catches my eye as a local kid purchases a “Snacks” chips from one of the vendors on his way to school, causing nostalgic memories from my own childhood to flood my mind. The fourth salon on the street we’re driving on has just opened. Just next door, a man sits in a red transport container surrounded by all sorts of fabrics and textures as his hands work the sewing machine, feeding the dress fabric into the machine effortlessly. Car washes, sheebeens, takeaways and airtime distributors can be found on almost every street. I marvel at the spirit of entrepreneurship and creativity present in the townships.

Hair dresser or dress maker, teacher or business owner. For many, it is paid work that is considered an ‘occupation’. However, for the extraordinary human beings known as Occupational Therapists, the word ‘occupation’ is considered a multi-faceted phenomenon referring to daily activities that enable people to sustain themselves, contribute to their families and participate in broader society (Brown, 2013). We as OT’s view occupations as fundamental to human health because they provide meaning, identity, and structure to people's lives and more importantly, can reflect a society's values and culture (Brown, 2013). Thus, in community practice for us to truly understand a community, we must first understand its occupations.

Observation and literature on a community may provide us with some knowledge about its people, cultures and its history however, it also gives rise to a multitude of stereotypes.

“Three alleged criminals shot dead in shoot-out with police in KZN”

“Suspects arrested after shootout with police in Clermont”

These are the first two news articles that pop up after a quick google search of Clermont-KwaDabeka. Immediately, we’re quick to associate all of Clermont’s residents with crime, violence and lack of morals. What about those residents who work hard at their daily businesses to provide for their families or save towards their children’s university funds? Or the sense of comradery amongst community members ? These are the things you’re only truly able to understand by immersing yourself within the community and its occupations, its culture.

One way to immerse ourselves within the community is to engage in the occupations of its people. Thus, my team and I found ourselves on the side of the road, taking over a local’s informal mielie business for lunch. Braaied or boiled, Zandile’s mielie stand had you covered.

Zandile’s oven consisted of concrete cement slabs and logs of wood in various sizes. A pot with water is set atop the wood fire to boil some of the mielies whilst the steam from the fire is used to braai the others.

Every morning she breaks large branches of wood and skilfully places them to get the best fire. Breaking the branches is no easy task and my colleague and I struggle for a good 5 minutes before giving up and seeking the expert Zandile’s assistance.

Next, Zandile uses a match and piece of plastic chair to light the wood on fire. This is a dangerous feat as she reveals what looks to be a partial thickness burn on her middle finger. A long walk up the hill from her mielies spot, is a tap that she uses to fill her bucket and pot with water. This water is then used to boil the mielies or wash her hands. With no oven mitts or protection, she lifts the hot metal lid of the steam pot effortlessly. The smoke arising from the fire hardly affects Zandile but my own eyes start to sting forcing me to turn away. I am barely able to keep up with the physically demanding, almost dangerous nature of this occupation yet she performs it with such ease.

Whilst waiting for the mielies to get done, Zandile speaks to us about how she grew in the street trading business. My colleagues and I were surprised that she had completed a business course offered by her local church which aimed to empower her and improve her independence. “Purpose initiates the activity of occupation, and meaning is a complex, unconscious process mediated by affective and social elements”. (Morrison et al., 2017)”. Zandile started her mielie stand with the purpose of supporting her children and sending them to school. Thus, informal trading was more than just a means of survival but rather a step towards her and her children’s independence.

Street traders face a plethora of challenges running their informal businesses (Sassen, 2013). In her own business, one such challenge that Zandile experiences is the competition between other informal businesses that sell the same or similar products as her. Secondly, the politics between mielie suppliers sometimes result in war which affects Zandile’s own ability to carry on with work engagements. A third challenge includes the fact that Zandile is generally forced to keep her prices very low, to sell her goods in a competitive market. Another challenge that Zandile faces is the fact that her business remains unsheltered at the mercy of criminals and natures elements. Thus, community politics, issues of power and daily physical constraints are factors that lie outside Zandile’s control suggesting the potential for her to experience occupational injustice.

Women street traders face their own specific challenge of juggling multiple roles, including home and community maintenance as well as reproductive roles, with productive street trading activities (Von Broembsen, 2008). This can result in occupational imbalance.

In addition to this, the socio-economic and political context of South Africa notably influences street vending. South African legislation does not recognize street vendors as being economically active members of society engaging in productive occupation (Gamieldien, van Niekerk, 2014). Legislation does not support their contribution to the South African community and many of them experience occupational marginalization and occupational apartheid. Thus, street vendors such as Zandile are unable to transition to small owned business enterprises rather than just informal businesses.

In conclusion, there is an opportunity for occupational therapists to liaise with other government sectors, outside of health, to influence regulations governing street vending and to aide informal businesses such as Zandile’s in accessing financial services, business development skills, infrastructure support and amenities access. Street businesses provides individuals with a sense of pride in overseeing their own welfare, as well as in their legitimate contribution to the economic growth of families, communities and South Africa at large (Gamieldien, van Niekerk, 2014). For occupational therapists this is an invitation to improve our understanding of this occupation.

OT out!

REFERENCES

Brown, H.V. (2013) The meaning of occupation, occupational need and occupational therapy in a military context. Physical Therapy, 93(9), 1244–1253.

Morrison, R., Gómez, S., Henny, E., Tapia, M. and Rueda, L. (2017). Principal Approaches to Understanding Occupation and Occupational Science Found in the Chilean Journal of Occupational Therapy (2001–2012). Occupational Therapy International, 2017, pp.1-11.

Gamieldien, F., van Niekerk, L. (2017). Street vending in South Africa: An entrepreneurial occupation. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy, 2017; 47(1): 24-29.

Von Broembsen, M., 2010. Informal business and poverty in South Africa: Rethinking the paradigm. Law, Democracy & Development, 14(1), pp. 1-34.

Sassen, S.R.,(2013). Women’s experiences of street trading in Cape Town and its impact on their well-being (Unpublished master’s thesis).University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa.

0 notes

Photo

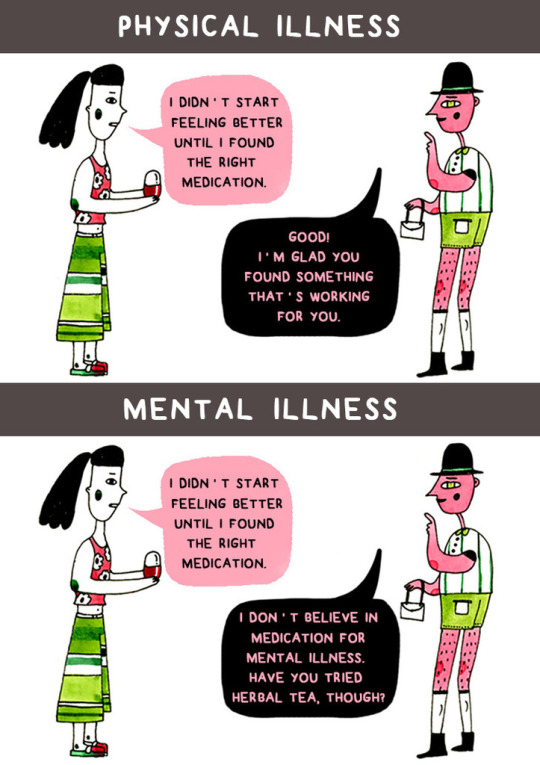

How We Treat Mental Illness Vs. How We Treat Physical Illness

321K notes

·

View notes

Text

Money Makes the World Go Round

“Sesifikile!” announces Uncle. Our search for home visit clients in the community has led us to the foot of one of KwaDabeka’s many grassy hills, sprawling with informal shacks that are often no bigger than a single room. Made from corrugated iron, plywood and plastic sheets, the shacks offer little protection from the outside elements. Water flows down the concrete pathway leading up the hill, into the litter filled drainage on the side of the tarred road below. A little boy cries in the distance whilst another wanders around naked in the suffocating heat. The smell of poverty hangs heavy in the air as we begin our trek up the mountain to the house we intend to visit. Veering off the concrete path, we find ourselves hopping over piles of litter and dodging wet, muddy pits that are a questionable shade of green. The thought of how easily communicable diseases may be spread in such an environment crosses my mind.

With the slope of the hill steepening, I no longer trust my feet to maintain their grip regardless of the advanced design of my Nike sneakers that now feel so excessive. Only then, does my privileged, able-bodied self, comprehend the frightening reality of how incapacitating this low socio-economic, poverty-stricken environment is to those with disabilities. I begin to question the economic state of our country and the debilitating affects it has on the health and quality of life for many South Africans.

As a health professional, it is no secret that socioeconomic factors can determine an individual’s overall well-being (WHO). Income, housing, employment, education and access to health care services are some of these economic determinants of health. (Senterfitt, Long, Shih & Teautsch, 2013). These factors are interrelated and cyclic in nature with the cycle often starting with income and economic status.

Easterlin et al. (2010) found that an increase in income facilitates the fulfilment of a greater number of needs, leading to the attainment of higher levels of well-being (as cited by Mafini, 2017). Individuals with high economic statuses were also found to present with greater life satisfaction (Mafini, 2017) as their environment and available resources supported their engagement in meaningful occupations. The suburb of Westville is an example of a community with a middle to high socioeconomic status that experiences this level of satisfaction and needs fulfilment. Not a stone’s throw away from this upper-class suburb, lies the contrasting Clermont-KwaDabeka township where many households suffer from the gruelling effects of poverty that result in ill-health because it forces people to live in environments that make them sick, without decent shelter, clean water or adequate sanitation(WHO).

Poverty can also result in occupational deprivation which can be defined as “a state in which people are precluded from opportunities to engage in occupations of meaning due to factors outside their control (Whiteford, 2000).” For example, in KwaDabeka, a lack of finances limits an individual’s opportunity to seek higher education through university or community colleges even though this is something that is valuable and meaningful to them. Hence, life after school results in unemployment and further poverty.

Employment is seen as another economic determinant of health. South Africa has an unemployment rate of 26.7% and a youth unemployment rate of 51.91%( Moya, 2018). Whitney M Young once said, “The hardest work in the world is being out of work.” Research indicates that unemployment affects an individuals overall mental health with stress, depression and low self-esteem being some of its psychosocial effects (LexisNexis, 2009). Many of KwaDabeka’s inhabitants are unemployed, especially the youth and spend large amounts of time unconstructively leading to occupational imbalance. Occupational imbalance refers to an individual or group experience in which health and quality of life are comprised because of being unoccupied, over occupied or under-occupied (Brown, 2013). This coupled with the psychosocial effects of unemployment result in substance use and addiction, a common problem that was identified by community members.

Another economic determinant of health includes a lack of access to effective health care services. According to Groenewald (2017), South Africa was ranked last among 19 nations in a global survey that measured healthcare system efficiency (Groenewald, 2017). This was attributed to average healthcare spent as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) that delivered below average health outcomes; whilst South Africa spends 8.8% of its GDP on healthcare, the US spent 19.1% of their GDP on health and France 11.5%. Unequal distribution of resources and burden of work placed on health professionals are other factors that impact on the efficiency of South Africa’s health care system as treatment is often delayed due to scarce resources (Seekoe, 2007). This is evident in the KwaDabeka township, where there is only one occupational therapist for the KwaDabeka Community Health Centre. This CHC serves a population of approximately 109 855, all of whom reside in the KwaDabeka catchment area (KZN Department of Health, 2018). With a 1:109 855 ratio, no wonder there is a lack of service delivery to all who need it.

Long queues at Clermont Clinic.

Whilst researching the economic factors that impact on health, I couldn’t help but relate many of them to one of my client’s from psychosocial block at a substance abuse rehabilitation facility; ‘N’, was a young women from Clermont, bursting with potential to be great but instead was roped into the world of Whoonga. From a young age, problems stemming from the poverty in which she lived made her vulnerable to addiction. She failed to develop a relationship with her mother who relocated for employment purposes and grew up without knowing her father. From as young as 6, she was expected to carry out IADL task such as cooking, cleaning and laundry whilst living with a family that was not even her own. Abuse and violence was a common occurrence to her. Many of these events resulted in the development of ineffective coping skills which ultimately led to her addiction. Due to a lack of funds, she was unable to complete an admin course at Elangeni college. She was fired from her job due to her addiction and was unemployed ever since. This occupational imbalance only worsened her addiction. Whilst she was able to receive free health care services at the rehab, with only one occupational therapist in the KwaDabeka catchment area, there was a lack of carry over and monitoring that were essential to prevent relapse.

It was the application of the information researched to this case study that gave me greater insight into the reality of the people living in poor economic townships like Clermont-KwaDabeka. Many of the people living in these townships are full of potential to achieve great things yet are not afforded the opportunity to do so. In turn, they are vulnerable to ill health and well-being. Hence, as health professionals we must play our part to prevent people like ‘N’ from going unnoticed and uncelebrated in this world.

OT Out!

REFERENCES:

Senterfitt, J.W., Long, A.,Shih, M., Teatsch, S.M. (2013). Social Determinants of Health; How Social and Economic Factors Affect Health.

Mafini, C. (2017). Economic Factors and Life Satisfaction: Trends from South African Communities. Acta Universitatis Danubias, 13

Whitefor, G. (2000) Occupational Deprivation: Global Challenge in the New Millenium. SAGE journals.

World Health Organization. (2018). The determinants of health. Retrieved from: http://www.who.int/hia/evidence/doh/en/

Moya, S. (2018). South Africa’s Jobless Rate Falls to 26.7% in Q4. Trading Economics: Retrieved from: https://tradingeconomics.com/south-africa/unemployment-rate

LexisNexis. (2009). The psychological impact of unemployment.[online]. Available at: https://www.lexisnexis.com/legalnewsroom/workers-compensation/b/workers-compensation-law-blog/archive/2009/06/25/the-psychological-impact-of-unemployment.aspx?Redirected=true

Brown, H.V. (2013) The meaning of occupation, occupational need and occupational therapy in a military context. Physical Therapy, 93(9), 1244–1253.

KZN Department of Health.(2018) Retrieved from: http://www.kznhealth.gov.za/kwadabekachc.htm

Groenewald, Y. (2018) South Africa last in healthcare efficiency study. fin24. Retrieved from: https://www.fin24.com/Economy/south-africa-last-in-healthcare-efficiency-study-20170609

E. Soekee. (2007). Poverty and health in developing countries: a South African perspective. Diversity in Health and Social Care.

0 notes

Text

CommUNITY

The sound of music emanates from both the UKZN taxi radio & the surrounding homes as we drive through the Clermont-KwaDabeka townships, our work space for the next 6 weeks. The occasional hoot from Uncle (our transport driver) accompanied by a friendly wave to passers-by indicate a familiarity that exist between him and the community members. Little children race around the street as they enjoy their school holidays stopping in their tracks to sometimes stare & wave at the strange ladies in green uniforms. Adults attempt to complete their chores for the day, with some washing and hanging their clothes whilst others wash their cars or run their small, informal businesses. A few community members sit outside their homes, drinking cold beers with each other, in the hope of cooling down from the intense heat beating down on the mountains. Their brick homes and shack dwellings provide little protection from natures elements in the low socio-economic township that is Clermont. Welcome to fourth year’s community module!

COM-MU-NI-TY

It is a word derived from the Latin “communis” and is a construct that has been studied by various scientific disciplines. Fransen, (2005) defines community as a unit that has a historical depth in time and a place where people share a sense of connectedness that goes beyond living within the same geographical location. Just like people, communities have their own stories with a past, present and future (Fransen, 2005). Clermont- KwaDabeka has a rich history as the township itself was developed in the 1960s as a temporary settlement for migrant labourers. During the apartheid days, the township was a black middle-income township (SA History Online, 2017). Since the end of apartheid Clermont has been sprawling with shacks as people from the rural areas come and seek work opportunities in the nearby suburbs of Westville, New Germany, Pinetown and Durban. Currently it is littered with informal settlements plagued with high crime rates, high levels of unemployment and an overall sense of poverty.

In a utopian world, the future of all communities, including KwaDabeka would be one of well-being, growth, development and inclusion of all. It is a future where people recognise and develop their potential & abilities to respond to their own needs & problems within the community with minimal external support. Ideally, it is a future that supports the use of assets to promote social justice and help improve the quality of community life for all such that individuals, especially children, escape the seemingly endless cycle of poverty. However how do we achieve this?

Upon researching this question, I came across the ‘Prevention Institution’ which, according to its website, is a non-profit organization that synthesizes research and develops tools that promote innovative community-oriented solutions(. One of the tools that they have developed is called THRIVE which is used to assess communities and identify structural drivers in terms of 1.)social-cultural environments 2.)physical/built environments and 3.)economic/ educational environments that enable communities to flourish.

The socio-cultural factors within any community can include a) the value that individuals place on activities that aim to uplift their community and b) the norms and culture of the community. If members are motivated and perceive themselves to be capable of effecting change in the environment, then this promotes well-being within the community. These factors then influence the level of participation of community members. Fransen (2005) supports the notion that community involvement is a necessary condition for success. In Clermont-KwaDabeka, we see that many of its community members operate on a passive participatory level. There is an air of inactivity & perception of helplessness that has been passed down by previous generations. Therefore, the need to accept responsibility for community action is not valued leading to reduced community participation. Furthermore, they have developed a dependence on OT students and other community-based rehabilitation professionals. Hence, there is a lack of carry over of projects and little to no implementation of skills taught to them. This was evident in the staff at facilities within the community which include day care centres, schools, CCG’s and societies for the aged.

Physical factors that promote community well-being include aspects such as safety, accessibility, housing and other infrastructure within the community.

In 2016, KwaDabeka had the 4th highest murder rate and in the same year Clermont was considered one of the most unsafe areas in the eThekwini district (SAPS Crime Stats In eThekwini, 2017). These high crime rates impact on community participation as many members may be afraid of leaving their home for fear of being mugged, raped or subjected to violence. This impacts on the community’s overall ability to perform occupations.

Inaccessibility within the Clermont area is also seen as a major inhibitory factor as narrow roads and steep hills limit the mobility of those in the community with disability and disease. Hence, these individuals are excluded from work, social and IADL occupations. Their true potential to contribute towards community development will be forever lost.

Lastly, we look at economic/educational factors. A middle to high socio-economic community is more likely to flourish as its members are financially able to contribute towards its betterment. Furthermore, individuals can seek private services including health services resulting in greater well-being. They can afford to attend colleges and other institutions to further their knowledge resulting in better job prospects and better life opportunities. However, in a low socio-economic area such as KwaDabeka, many families live in poverty and are unable to send their children to tertiary institutes. Hence, the next generation becomes stuck within the seemingly endless cycle of poverty.

In a TED talk by Cormac Russel (watch here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a5xR4QB1ADw), Russel emphasized the need for community workers and professionals to focus on “what’s strong not wrong” with the community. Only after watching this had I realized how much emphasis my colleagues and I were placing on the deficiencies and pathology of the community. Rather we should acknowledge the skills of its local residents, the power of the social networks within KwaDabeka and the positive stories of shared lives in the community.

In conclusion, rather than focusing solely on removing the weeds from the garden that is KwaDabeka, we should focus on watering and nourishing the seeds that already exist within the community in the hope that these seeds flourish and bloom. Here’s to providing solutions that have long roots in the culture and perceptions of the people and their communal histories to really create a difference within the community.

OT out!

REFERENCES:

Fransen,H. (2005). Challenges for occupational therapy in community-based rehabilitation: occupation in a community approach to handicap in development In Kronenburg, F. Algado, S.S. Pollard, N.(Ed) Occupational Therapy Without Borders. (pp 166-183) United Kingdom, UK; Elsevier Limited.

SAPS Crime Statistics in eThekwini. (2017). retrieved from: http://www.durban.gov.za/City_Government/Administration/city_manager/RAPA/Reports/2015-2016%20RAPA%20SAPS%20Crime%20report.pdf

South African History Online. (2017) Clermont. Retrieved from; http://www.sahistory.org.za/place/clermont

Eatbettermovemore.org. (2018). THRIVE: Community Health Approach. [online] Available at: http://www.eatbettermovemore.org/thrive/communityhealth.php

0 notes

Text

‘Mental health disabilities are an illness not a weakness.’

‘Mental illness is an issue not an identity’

Watch JacksGap’s video below!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gkZiBnL0h7Y&feature=share

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jar of Life

A person once said that “student life is golden life” as it is the most important part of human life. It is supposedly a period of joy and happiness because the minds of students are free from cares and worries of an adult life (Prakash, 2015). Well, whoever came up with that saying obviously never knew any OT university students because boy oh boy are our minds flooded with stress and worry as we drown in the chaos that is our student life reality.

At this stage in our life, being an OT student is our primary role; a role that can become so encompassing that we often abandon other things that are considered important to us like our family, friends and health.

Our clients garner more of our attention than our family as we spend most of our time locked in our bedrooms, performing research and planning for their treatment, striving to provide the best intervention for them whilst still trying to impress our supervisors. Our clients own mental and physical health become more important than our own as we refuse to miss a fieldwork day. The bonds we form with our OT classmates strengthen whilst the bonds of other friendships begin to fade as school friends are unable to relate to the taxing work that comes with our degree. We forget how to prioritize as we become consumed and overwhelmed with finishing our degree.

When life overwhelms us like this, it is important to refocus on what is truly important and dear to us. The story of the “Jar of Life” helps put into perspective the importance of prioritizing those things which are of value to us (read story here: https://balancedaction.me/2012/10/17/the-jar-of-life-first-things-first/).

Our life as OT students is the sand within the jar; a somewhat insignificant factor in the grand scheme of life. By filling in the sand first, there is no place for our golf balls like our family, friends, health and sometimes even religion. How then are we supposed to achieve a sense of fulfilment and satisfaction without these core components? The answer is you can’t.

It is therefore essential that we find the time and space for these very important parts of life as without them we experience emptiness and unhappiness. And whilst the sand may blow away or leak from a single crack in the jar, the golf balls will always remain a steady component within the jar.

OT Out!

References;

Prakash. 2015. Student Life is Golden Life. Retrieved from: https://www.importantindia.com/20305/student-life-is-golden-life-short-essay/

1 note

·

View note

Text

A scary state of affairs

October is a month best known for its celebration of Halloween! A night of embracing the weird and wonderful, a time to unleash your inner monsters and express your superstitious beliefs! Or so it is for many people around the world.

However, in South Africa, October is a month of celebrating a different type of weird and wonderful; it is a month for celebrating those with mental illnesses and creating awareness into the horrors that these people sometimes face.

According to an article published in the Sunday Times, Tromp, Dolley, Laganparsard & Govender (2014) state that more than 1/3 of South Africans suffer from mental illness and a scary 75% of this population will not receive treatment.

As future health professionals it is important to question why such a large portion of the population we will serve do not receive the treatment so desperately needed.

In South Africa, mental health is still heavily stigmatised within the local community. It is often not recognised as a legitimate illness that should be treated medically. In Zulu culture, mental illness is seen as a form of witchcraft and is understood supernaturally rather than scientifically by the people within the community. People resort to prayer and use of traditional healing methods rather than medical western medication. This leads to further decline in overall mental health and can explain why many people may not seek professional intervention.

According to Tromp et al. (2014), 17 million South Africans are dealing with depression, substance abuse, anxiety, bipolar and schizophrenia. Yet despite the seriousness of this situation, the department of health only spends 4% of its budget annually to deal with this crisis. The inadequate budget and poor resource allocation towards ensuring mental health and wellbeing is evidence of how mental illness has been neglected in South African policy. Neglect in combination with corruption also leads to inadequate service provision and can sometimes result in the deaths of mentally ill patients as seen in the Life Esidemeni tragedy. The tragedy has resulted in many people losing faith in the health care system and may affect people’s decisions to seek intervention for themselves or their loved ones for fear of similar outcomes.

The budget allocated to mental illness proves insufficient and cannot cover the costs of training PHC personnel in mental health care, mental health promotion and prevention programmes, as well as psycho-social rehabilitation resulting in a lack of properly trained staff. Studies have found that there are only 290 registered psychiatrists, providing a physician to population ratio of 1:183,000.

The lack of appropriate staff and mental health professionals, in combination with a lack of specialized state hospitals, result in inadequate care and provision of services with many mentally ill patients slipping through the cracks of the broken health care system. This too may explain the reason why many individuals with mental health issues will not receive treatment.

In conclusion, South Africa needs to prioritize mental health and put in place an appropriate health care system that will ensure individuals are able to seek psychiatric intervention. The government must recognize the need for the development of specialized psychiatric hospitals and invest in the training of staff and physicians that will be better equipped to deal with mental illness. Only then will it win back the trust of South Africans.

OT out!

References

The South African Depression and Anxiety Group (2014). SA’s sick State of Mental Health. Retreived from: http://www.sadag.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=2178:sa-s-sick-state-of-mental-health&catid=74&Itemid=132

https://www.thedailyvox.co.za/life-esidimeni-the-forgotten-people-of-south-africas-healthcare-system-nikita-ramkissoon-benazir-cassim/

1 note

·

View note

Text

Sexual ID for ID

The road trip that was term 1 semester 2 has finally come to an end! These past two weeks have seen me sputtering, stalling and steaming all the way to the pit stop that is our September break. With my engine burnt out and in desperate need of some repair, I decided to take the first few days of this holiday to refuel (hence the late blog post) and catch up on some much needed sleep and nutrition by eating myself into an oblivion. So yes, one may notice a newer bumper and bigger headlights on the framework of my body after this holiday and there are no regrets about it.

During these 4 days, in between picking Dorito crumbs of my shirt, I was able to reflect over the term and the people I’ve worked with, especially individuals with Intellectual Disability. One particular aspect that I found rather intriguing about Intellectually Disabled individuals was their sexuality and ability to form intimate relationships. I found that the clients I have worked with over the past 2 years with this diagnosis ranged from having a complete aversion to sexual or intimate relationships with the opposite gender to excessive participation (or wanting to participate) in sexual activities . It made me think about the possible reasons as to why these 2 extremes existed. Having known parents and family of ID individuals, I questioned the role that society and family played in the development or inhibition of these individuals sexual identity.

A qualitative study conducted in Ireland by Healy, McGuire,Evans & Carley (2009) assessed the sexual knowledge, experiences and aspirations of service users and examined their perceptions of barriers to achieving sexual autonomy. The study noted that participants had recognized that secrecy and deception were needed to exercise sexual rights. The participants also reported a general reluctance of family members and carers to acknowledge and respect their sexual rights. This is evident in the strict rules and regulations that govern many of the facilities used for fieldwork placement, rules that see that individuals are punished for expressing their sexuality or participating in sexual behaviours. Research has shown that negative carer attitudes are internalised by people with an ID and lead to negative attitudes towards their own sexuality (Cuskelly & Bryde 2004; Murphy & O’Callaghan 2004 as cited in Healy et al. (2009)).

Another study by Bleazard (2010) about young women with ID and their perspective on their sexuality was conducted in South Africa with the aim of a) understanding the sexuality needs and concerns of young women with intellectual disability in an attempt to make public their private needs and concerns, b) attempt to establish the dominant views of the educators who are in daily contact with these young women and who are directly and indirectly responsible for sexuality education and c) gauging parents’ perspectives on the sexuality needs of their children. The study found that participants had poor knowledge about a variety of concepts including menstruation, contraception, STI’s sex and pregnancy. This was attributed to a lack of discussion between the individual and their carers/educators as well as the surrounding dependent role enforcing environment. Furthermore, the study found that educators and carers did not believe that individuals with ID were capable of fulfilling sexual roles or even motherly roles later on in life. Other interesting finds from the study included that more than 80% of the educator respondents thought that it was unrealistic to expect a disabled person to make decisions about their own sterilization, while 42% agreed that it was best for intellectually disabled young women to be sterilized.

The study also explored the themes of fear and reluctance of parents to allow autonomy for their children due to violence and other dangers in the South African environment. “Fear and restriction have implications for the development of relationships outside the home and the learning of social skills” (Bleazard et al., 2010) and an overprotective family can inhibit participation, identity and freedom.

Both these studies allowed me to understand in greater depth, the role of parents and educators in the development of sexuality within intellectually disabled individuals. Their lack of sexual intimacy or excess thereof can be linked back to 3 important factors: 1) the distorted perceptions of their parents and educators, 2) the lack of education and discussion about topics related to sexuality received from their parents/educators and 3) the fear of exploitation and vulnerability to violence that parents have regarding their children with ID.

As future occupational therapists, we should aim to combat the distorted perceptions of parents and other health professions about the capabilities of ID individuals by educating them about the importance of equipping their children with the most important tools to enable them fulfill normal roles within society such as the role of husband, wife, mother, father, grandmother or grandfather; the tools of education and belief. Belief that they ARE capable of fulfilling their roles and are able to engage in intimate relationships and education about the components needed in order to ensure the success of these relationships and safety of these individuals. Society needs to change its views about ID individuals and provide opportunities for them to develop their sexuality without ridiculing them for the mistakes that they may make on the way. These articles have really opened my mind and have influenced my own perceptions about treatment of individuals with an ID diagnosis. It has made me realize the importance of advocating for these individuals throughout my student and professional career.

OT out!

REFERENCES

Healy, E., McGuire, B.E., Evans D.S. and Carley S.N. (2009). Sexuality and personal relationships for people with an intellectual disability. Part I: service-user perspectives. Journal Of Intellectual Disability Research.

Bleazard, A.V. (2010). Sexuality and Intellectual Disability: Perspectives Of Young Women With Intellectual Disability.. Ph.D. Stellenbosch University.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Signing off on midterms 🤙🏽

0 notes

Text

Whining and Dining

Diagnosis: OT student induced psychosis

Diagnostic criteria:

1) overall irritable mood,

2) binge eating with weight gain

3) lack of sleep and

4) severe impairments in social functioning.

Third year class of 2017 meets all 4/4 criteria for this diagnosis.

Midterms have finally drawn to a close with all of us feeling a sense of elation for surviving this 5 week term. There’s no better way to celebrate the end of midterms than whining and dining with your OT colleagues, sharing the knowledge you’ve gained(or didn’t) and the experiences you’ve had(or haven’t) with your supervisors and fieldwork group alike. That’s exactly how I decided to spend my Friday afternoon; an afternoon spent complaining about the intricacy of SMART aims, retelling humorous stories about our clients and reflecting over our overall training experiences.

Whilst some of my colleagues felt as if they had gained close to nothing on this block, I and a few others viewed it as an essential learning curve. Reflecting back on the choices I had made with regards to my treatment I now realize how many vital points I had missed.

Shamefully, I must admit that instead of working at a consistent pace with my clients treatment, my attitude was more of a “what is a therapeutic activity for tomorrow’s session” rather than a “what is the bigger picture of the clients problems”. This was evident in my case formulation where the activities I had performed with the client did not reflect critical thinking and clinical reasoning in the broader context of my subprogram and also affected the success and therapeutic value of my treatment.

I also realized the importance of conducting my own research through books, the internet or active engagement with my lecturers regarding the theoretical aspects of psychosocial study that includes the models, applied frames of references, programmes and subprograms that could be utilized with certain diagnosis as these play a vital role in ensuring successful intervention. It was for these reasons that I was rather underwhelmed with my performance this term, perhaps the most underwhelmed in comparison with all 3 previous blocks in the past 2 years.

Another aspect that I found difficulty with was exercising assertiveness and handling my client firmly when need be. It’s ironic how as OT’s we’re supposed to be teaching our clients these skills yet sometimes we ourselves lack them.

Whilst recognizing the negatives of my own behaviour, I only see it fit to make mention of the growth that I’ve experienced this prac. This includes the greater understanding and appreciation I have for group work and the theory behind it. Time and time again my colleagues and I have expressed how profound the effects of group work are within the mental health field. I’d go as far as to say it is a developing belief of mine that will most definitely become part of my identity as a future OT.

Another growth defining moment for me was finally understanding the difference between didactic therapy as compared to more occupation based therapy and knowing when to use what. One factor that really displayed my maturation this term was also my ability to deal with constructive criticism without taking it as a personal attack.

All in all, midterms has said its final goodbyes. With finals lurking around the corner, it’s best we be safe by actually using the knowledge learnt thus far as a weapon that will arm us in the weeks to come. Here’s to absolutely dominating and killing finals!

OT (knocked) Out!

1 note

·

View note

Text

Casual Day FOMO!

Sawubona! Dumela! Molo! Goeie More! Namaste! Nǐ hǎo! Assalamualaikum! It’s amazing how many different ways one can say “hello” when living at the very tip of Africa. South Africa is a place teeming with individuals of different races, ethnicities, cultures and religions, all mixing together to form the Rainbow Nation. Add in 11 official SA languages and you have a recipe for diversity that cannot be matched anywhere else in the world. And what better way to remind ourselves of our country’s cultural diversity than choosing it as a theme for this year’s Casual Day celebrations.

Casual day is a day dedicated towards raising awareness and funds for people with disabilities. Many companies, businesses and even schools celebrate this day by wearing fun clothes that match the theme chosen for that year provided that the employees or students pay a fee to do so. The funds raised are then seen as a contribution towards one of the country’s most vulnerable sectors of society; people with disabilities. As OT’s we jump at any chance to raise awareness for people with disabilities and so naturally we were made to plan a full Casual Day event for the service users at our fieldwork venues.

With “FUN” being the main goal in mind, my fieldwork group and I set out to ensure that the day would be one full of excitement, enjoyment and celebration of SA’s diversity.

Games (check), photobooth (check), delicious snacks (check), all OT students ready and on standby (not checked); the first Friday of September every year is Casual Day however this year it also happened to be the Islamic day of Eid Ul Adha. And whilst everyone else celebrated cultural diversity together at the challenge, myself and 1 other colleague (Hi Aziza!) were off celebrating our own cultures with our families and participating in the festivities that accompany this important Islamic yearly event.

And whilst I experienced some serious FOMO (fear of missing out) for missing the opportunity to bring joy to the clients I have grown so close to as well as the other service users at the challenge, I found happiness in knowing I at least contributed towards the planning of the games and activities as well as the sponsorship of the snacks for the service users.

So in essence, my heart was between 2 places on this special day; not only was I able to fulfill my role as a Muslim by celebrating Eid Ul Adha, I was also able to fulfill my role as an OT by bringing happiness to people who have become very special to me. That itself is an achievement.

OT out!

#casual day#Occupational Therapy#people with disabilities#cultural diversity#South Africa#rainbow nation

1 note

·

View note

Photo

TRUST FALLS! 🙌🏽

1 note

·

View note

Photo

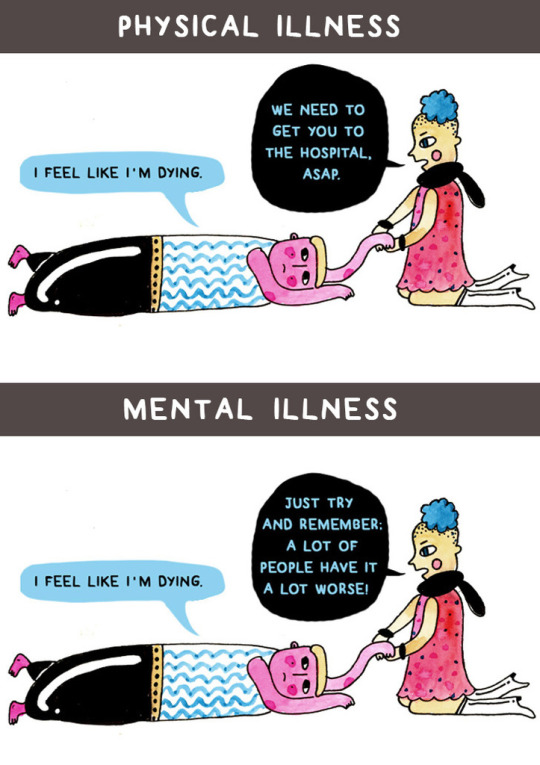

Learnt about using poetry as an alternative medium for therapy in class last week. This was the poem I chose to share as it accurately displays society's double standards. We have to acknowledge that these double standards are the cause for multiple mental health issues. Relatable & relevant.

6 notes

·

View notes