Wine, women, and song. Art, beauty, and life. Liberty, ecstasy, and recipes for really tasty drinks. Women may be naked, beauty may be subjective, and ecstasy is not a chemical. Eleleu! Iou! Iou!

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Dionysos References

Books of Myths, Poetry, Hymns, and Plays Involving Dionysos:

The Bacchae

The Frogs

D’Aulaire’s Book of Greek Myths

The Complete World of Greek Mythology

Dionysiac Poetics and Euripides’ Bacchae

Dionysiaca

The Glory of Hera <— take this one with a grain of salt, as it presents Freud’s theories as credible

The Library

Academic Texts on Dionysos and His Cult:

Dionysos: Exciter to Frenzy <— favorite

Pagan Regeneration, chapter iii: Dionysian Excesses

Dionysos: Archetypal Image of Indestructible Life

Dionysos (Gods and Heroes of the Ancient World)

Ecstatic

The God Who Comes: Dionysian Mysteries Revisited

The Glory of Hera

A Mythological History of Ancient Greece. Volume 1: In the Beginning

Dionysos in Archaic Greece: An Understanding Through Images (Religions in the Graeco-Roman World)

Mystic Cults in Magna Graecia

The God Who Comes: Dionysian Mysteries Revisited

Gods of the Greeks

Dionysus: Myth and Cult

Ancient Mystery Cults

Books on Ancient Greek Culture:

Religion and Art in Ancient Greece

Greek Religion: Archaic and Classical (Ancient World) <— favorite

The Gods of Olympus: A History

The Glory of Hera

A Mythological History of Ancient Greece. Volume 1: In the Beginning

Prayer in Greek Religion

Ancient Greek Religion (Blackwell Ancient Religions)

Race and Citizen Identity in the Classical Athenian Democracy

Human Sacrifice in Ancient Greece

Friendship in the Classical World (Key Themes in Ancient History)

Aphrodite and Eros: The Development of Greek Erotic Mythology

Girls and Women in Classical Greek Religion

The Homeric Gods: The Spiritual Significance Of Greek Religion

On Greek Religion: Cornell Studies in Classical Philology

“Reading” Greek Death: To the End of the Classical Period

From Death to Rebirth: Ritual and Conversion in Antiquity

Prayer, Magic, and the Stars in the Ancient and Late Antique World

Citizen Bacchae: Women’s Ritual Practice in Ancient Greece

The Greek Way of Death

Athenian Myths and Festivals: Aglauros, Erechtheus, Plynteria, Panathenaia, Dionysia

The Sacred and the Feminine in Ancient Greece

Psyche the Cult of Souls and Belief in Immortality Among Ancient Greeks

Gender and Immortality: Heroines in Ancient Greek Myth and Cult

Ritualized Friendship and the Greek City

Everyday Life In Ancient Greece

Siren Feasts: A History of Food and Gastronomy in Greece

Magika Hiera: Ancient Greek Magic and Religion

Myth and Thought Among the Greeks

Myth and Society in Ancient Greece

Myth and Tragedy in Ancient Greece

Magic in the Ancient Greek World

Ancient Magic and Ritual Power (Religions in the Graeco-Roman World)

Greek Mysteries: The Archaeology of Ancient Greek Secret Cults

Greek Religion: A Sourcebook

Ancient Greece: Everyday Life in the Birthplace of Western Civilization

The Greek Way of Death

Devotional Texts:

Written In Wine: A Devotional Anthology For Dionysos

Miscellaneous:

Athenian Myths and Festivals: Aglauros, Erechtheus, Plynteria, Panathenaia, Dionysia

Rain, Conceive! Ancient Mysteries of Demeter & Persephone; Dionysos; Percival

Old Stones, New Temples

Prometheus: Archetypal Image of Human Existence

thehellenicguy’s resources

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

“Stop.” Dionysus’s voice sounded strained. Slowly, Ariadne raised her eyes to look at him.

She saw his hands first, clenched in tight fists, but he did not strike her and the earth did not tremble, so she kept raising her eyes. She saw his chest next, his fast and heavy breaths stark through his open tunic. She saw his face last. His eyes pinched shut as his bottom lip turned white with the force of his teeth. If he were mortal, he would have bitten through the skin. He looked like he was in pain.

“Get up,” he hissed through his clenched teeth and bottom lip that looked like he might soon bite through it. She thought she misheard him. Gods were not forgiving. “Get up,” he cried, his voice cracking. “Please,” he whispered.

Ariadne stood. “My lord, I-”

“Stop,” Dionysus whispered. “I was joking.”

“What?”

He didn’t open his eyes. “I asked if you were calling the gods arrogant. I was joking.” He barked a harsh laugh. “We are arrogant.” His clenched fists relaxed and he fidgeted with the fabric of his tunic. “I didn’t mean to frighten you.”

Ariadne smiled at his pinched expression and damp eyes. “I wish I could tell you you didn’t.”

He met her eyes hesitantly. “You wish you could lie to me?”

Ariadne shrugged. Then she nodded. “It seems like it would be a comfort to you. But I think you would know I was lying.”

“I would.” Dionysus sighed and sat on the sand. He looked up at her after a moment. “Sit with me?” he asked.

She settled down in the sand beside him. She gazed at the horizon for a while before she found what she was looking for. She reached for his hand, but stopped, hovering over his wrist, a silent question in the air. He nodded. She took his wrist and guided his arm up until he was pointing at the small dot she had noticed on the horizon. “That’s Crete,” she murmured. “Have you ever been?”

“A few times,” he admitted. “A long time ago.”

Ariadne smiled as she let their arms fall to the ground, her hand still resting on his. “It’s beautiful.” She fell back into the sand, her hair in a halo around her. She saw his back shake with a soft laugh and he flopped back beside her. “I was isolated, but the beauty still surrounded me. I had a friend, Icarus, who used to live in my father’s palace. He was an inventor and an architect, just like his father, Daedalus. They would make the most beautiful things. Their designs had that kind of innate beauty that is only found in nature. Their skills in creation rivaled the gods.” She paused to gauge Dionysus’s reaction, but his breathing was steady and his hand stayed still under hers. “They were not arrogant, and Daedalus was never boastful. Icarus was, on occasion, but he was a child. But regardless of their own pride, their creations were seen as challenges to the gods and they were struck down without mercy.” Ariadne closed her eyes. “Some rumors say Icarus survived, but they’re rumors and to give them substance might draw undue attention to him.”

Dionysus knew she was testing him. He smiled at the sky where she couldn’t see. “I won’t tell.”

“I know,” she hummed. After a long moment, she sighed. “I shouldn’t trust you.”

Dionysus let out a breath he hadn’t realized he’d been holding in the silence. “I wish I could tell you that you should.” He paused. “I suppose all I can tell you is that I wish you would.”

“Why?” Ariadne asked, her voice suddenly loud in the night.

“I don’t know.” He rolled his head to look at her. Fates, she was beautiful. Her skin was as smooth as a pearl but as warm as an ember. Her light hair spilled into the sand around her, giving her an ethereal glow. Freckles danced on her cheeks like constellations, like some god greater than Dionysus could imagine had placed them there for all to admire. “I just do.”

She laughed and it sounded like bells. It rang through the air and settled on a cloud far above them like it was just waiting to rain down and bring joy to every person it touched. “I think I’d like to trust you too.”

Dionysus’s mouth split with his joy and he let his laugh join hers on the breeze. It filled the air with the scent of a vineyard and a crisp fall breeze, heavy with the passing of summer.

He ruined the moment when he opened his mouth too far and ended up with his tongue on the sand. Ariadne’s tinkling laugh turned into something fuller and from a deeper part of her soul. Dionysus felt his eyes warm and dampen.

“Are you alright?” Ariadne managed through her own tears of mirth.

Dionysus spat sand out of his mouth, taking care not to spit in her hair. “You are so beautiful,” he whispered. “Aphrodite herself should envy you.”

140 notes

·

View notes

Text

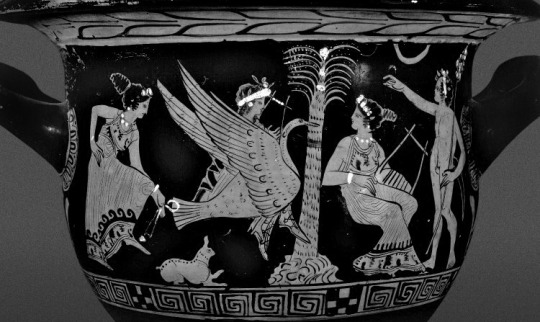

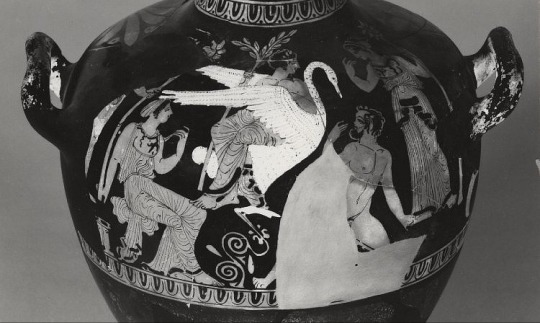

Apollo, returning from Hyperborea, is welcomed by the retinue of Dionysus

Red-figured bell krater, 400 - 380 BC

Red-figured hydria, 390 - 370 BC

The above ancient potteries depict the scene of Apollo's return to Delphi after his three months stay in Hyperborea. In the center, Apollo is riding on a swan, a bird closely associated with Hyperborea. He is wearing long flowing robes and his head is crowned with a fillet. On either sides, maenads and a satyr with thrysus look at Apollo with welcoming gestures.

According to legends, Apollo temporarily handed over Delphi to Dionysus every year before his journey to Hyperborea. No prophcies were issued during this time. Dithyrambs were sung instead of paeans and Maeands raved in the honor of Apollo as well. Upon his return to Delphi, Apollo was greeted by the followers of Dionysus, Artemis, Leto and his own followers. The Delphians held the annual festival Theophania celebrating the return of Apollo from his winter quarters in Hyperborea.

448 notes

·

View notes

Text

30 days of Dionysus - 17

Day 17 - How does this deity relate to other gods and other pantheons?

I’m going to focus on syncretism with gods from other pantheons because I think we’ve talked about how he relates to some deities in a lot of other topics.

One case of syncretism we quickly talked about is with Sabazios, a Phrygian/Thracian deity.

Then we have the roman syncretism with Liber. Again, Liber is originally a roman rustic god, which got associated with Dionysus pretty early on when Greek settlers arrived in Southern Italy.

The Greeks identified Dionysus with the egyptian god Osiris also very early on, as it was already a thing in the 5th century BC (according to Herodotus). Later, Plutarch also stated Osiris and Dionysus to be same, with important parallels around, for example, the notion of dismemberment and other cultic. This syncretism however is particularly important during the Ptolemaic era, since the dynasty claimed a divine lineage to Dionysus (which was a fairly common political thing to do, see Julius Caesar and Venus).

Lastly, and I’m putting this one aside because it is an in-pantheon syncretism: Hades. There are evidences of cultic parallels between a chthonic Dionysus and Hades, especially in southern Greece. Another interpretation is that it might have an implication in the Eleusinian mysteries under the form of a tripartite god joining Zeus, Hades and Dionysus representating birth, death and resurrection.

I don’t want to go into complicated details when it comes to syncretism and the different interpretations but being knowledgable about it serves as an important reminder: Dionysus and the other greek gods are very very complex, and no matter how much we, as worshippers, try to simplify things to make them more approchable to us and to newcomers, we can’t erase that complexity. We need to remember that the gods and their cultus are not set in stone, that the myths are various and contradict eachother, that cultus are also various and contradict eachother too.

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

30 days of Dionysus - 15

Day 15 - Any mundane practices that are associated with this deity?

The line between mundane and mystical is often thin in Hellenic polytheism but there’s a few things we can list.

Drinking wine/alcohol: The most obvious but also important one. I’ll cite Walter F. Otto : “He, the god who appeared among men with his ripe intoxicating drink, was the same as the frenzied one whose spirit drove the women to madness in the loneliness of the mountains. Wine has in it something of the spirit of infinity which brings the primeval world to life again.” Wine being holy in a dionysiac sense, drinking it can be both ritualistic and mundane. I like to extend this idea to most alcohols, because the state of drunkenness is dionysiac in nature.

DISCLAIMER: Before I get angry anons, I’m in no way saying that dionysian worshippers who do not drink alcohol are less pious than the ones who do. Drinking is a personal choice and if it’s not for you for whatever reason, then it’s fine and you get to focus on another aspect of Dionysus.

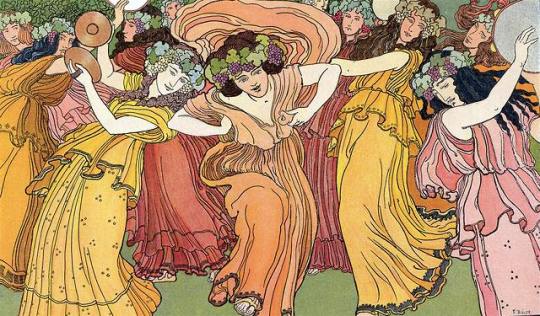

Dancing: Dance is a very common theme in bacchic frenzy, and it’s often done by the maenads/women. I think dancing is seen as the physical, visual representation of madness in Dionysiac cult.

Any form of dramatic art: Dionysus is the patron to theater. Acting, writing plays, going to see a play… all those are associated to him and make great devotional activities.

Drag: I haven’t touched on the subject of cross-dressing in Ancient Greek setting, but cross-dressing is a dionysiac activity and doing drag and/or appreciating drag is also a very appropriate devotional activity.

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

30 days of Dionysus - 8

Day 8 - Variations on this deity (aspects, regional forms, etc.)

That’s.. such a wide topic…

Let me start off by reminding everyone that ancient Greek cultus was not homogenous. Ancient Greece was a cluster of independant cities which, while sharing a pantheon, did things differently. So yeah, we’re gonna have plenty and plenty of regional forms and aspects for each god. I also want to point out that we’re also talking about a religion that changed a lot over the centuries. When someone now, in the 21th century, refers to “hellenic polytheism”, we’re talking about a simplified, unified, modernized version of the old cultus, no matter how recon you want to be. And that specific modern version is largely based upon the biggest ressource we have: Athens, and its golden age: the 5th century BC.

Now, if you’re historically inclined like myself and many others on this website are, you can dig into academical articles and books and find out more about more localized ways of doing.

As a said, there were many ways I could have gone with such a vague subject for today but I’m going to take the “regional form” route and talk about something I haven’t seen that much on tumblr yet: the thracian cult of Dionysus and its link to Orphism. This will be long, so I’m gonna put this under the cut and if you’re interested: buckle up.

Keep reading

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

30 days of Dionysus - 5

Day 5 - Members of the family – genealogical connections

That’s broad and general knowledge so I won’t go into detail here. More information can be found here. Keep in mind that myth is not set in stone and stories vary depending on cult.

Traditionally, his parents are Zeus and Semele. In Orphic cult, his parents are Zeus and Persephone. A more obscure lineage, linked to the Eleusinian mysteries, consider him as a child of Demeter also.

Because he is one of the children of Zeus, he has a lot of siblings. Among the “big” olympians we find Aphrodite, Apollo, Hermes, Ares, Artemis, Athena, Hephaesteus, Persephone. But yeah, all of Zeus’ kids are obviously his siblings.

As for his children, I’m going to stick with short n’ easy version we find on theoi.com:

He had 9 children that are gods and “11″ mortal children. I won’t focus on the mortal children, it is just important to know that most of them are the children he had with his wife, the deified mortal Ariadne: Eurymedon, Keramos, Oinopion, Peparethos, Phanos, Phliasos, Staphylos and Thoas. Most of them lived as lords or kings.

Now, for divine children:

Hymenaios: Disputed lineage, he is most often attributed to the union of Apollo and a Muse. In the version in which he is a son of Dionysus, his mother is Aphrodite. He is the god of weddings and wedding hymns.

Iakkos: The “3rd Dionysus”, appears only in eleusinian rites. His mother is either the titiness Aura or Aphrodite.

the Kharites: The Graces. Traditionally the daughters of Zeus and Eurynome. They are sometimes said to be the daughters of Dionysus.

Methe: the nymph-goddess of drunkenness.

Pasithea: A kharis, she is the wife to Hypnos, the god of sleep.

Priapos: Probably one of the most known of his children. Priapos is the god of garden/vegetal fertility and fertility as a whole. He inherited of his father’s connection with the phallus. He is traditionally the son of Dionysus and Aphrodite.

Sabazios: Thraco-Phrygian god of wine and vegetation. Only one source says he is Dionysus’ son. I call syncretism on this one personally.

Telete: Goddess of the initiation into dionysian Mysteries. Her mother is the nymph Nikaia.

Thysa: the goddess-nymph of frenzy during the Bacchic orgies.

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

30 days of Dionysus - 7

Day 7 - Names and epithets

Dionysus is mainly known under 3 names: Dionysus, Bacchus and Liber. Dionsysu and Bacchus (Bakkhos) are both Greek names, Liber is not really the “roman name”. Liber is actually a native italian rustic god who got syncretised with Dionysus when his worship spread out to Italy.

Now, I won’t list all the epithets because, oh dear, there’s so much. If you want a very good list (I won’t say complete because they’re not all here), check out this theoi.com page.

Instead of listing them all blindly, I will go through some ones that I’ve carefully picked because I like them or because they are relevant to my practice.

Akratophoros: the giver of un-mixed wine. It was common in Ancient Greece to mix wine with water, at least for the southern cities. “Cute” anecdote: the macedonians didn’t mix their wine, which was quite harshly criticized in Athens and made them spread the belief that macedonians were drunk af.

Antheus: the bloomer, in the sense of flowers. But I personally find this epithet to have a powerful symbolic potential.

Bromios: “loud” or “boisterous”. Less than the meaning, I mostly like that one of the explanations to this title is that he was born during a thunderstorm, and I like that version.

Eleuthereus: If I had had to choose only one it would have been this one. It is one of the titles I feel the closest to: the liberator, the deliverer.

Intonsus: “with/of” long hair. I love love love this one. Shared with Apollo, it refers to the fact that young men would only cut their hair once they reached adulthood. As such, Dionysus and Apollo are described as eternally youthful. But I’m a sucker for long hair and that’s that.

Lyaeus: “who frees from anxiety”. This one hits home in many ways.

Phallen: self explanatory. Also I like dicks. Joke aside, my practice has become more focused on the sexual and fertility aspects over the years.

Soter: This epithet is common among the gods, as it means “savior”.

Anyway, that was a very personal take on the many epithets Dionysus has. For anyone who is looking for more, I highly suggest taking a look at the page I’ve linked above and going further into research. I’ve found obscure epithets in articles and books.

102 notes

·

View notes

Text

when did we start describing impulsive actions as feral? i love it. real bonding moment between the meme community and the maenads, followers of dionysus, greek god of alcohol and insanity. the next step is for us to get cool sticks and go rave in the woods we should get on that asap

2K notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello, Dr. Reames! I absolutely love Dancing with the Lion, and I am especially fascinated by the mystery cult in the epilogue. Would you be able to elaborate on Orphic Dionysus, and maybe discuss what informed your writing of the initiation? (A side note: the line "This was what it meant to come face-to-face with an immortal: better never to be noticed at all" made my hair stand on end, as well as your "ineffably sad" descriptions of the god. The whole scene was incredible!)

Thank you. I’m glad you enjoyed it! At least one reviewer on Goodreads thought it was “very weird.” I think, perhaps, readers more used to genre Romance may not have expected a visit from the magical realism fairy. ;) (Funny, how we always notice criticism more than praise.)

Anyway, to your question: much of our evidence for any mystery cult comes from the Hellenistic era and later, but it seems there was some form of Dionysic mystery by the 5th century, at least. The earliest mystery cults seems to have been Eleusis, but the idea caught on quickly, and others developed during the Archaic and Classical (esp.) eras, until by the 4th century they were ubiquitous and most Greeks had been initiated into at least one.

Mystery cults came in two basic types: those tied to a particular PLACE, such as the rites for Demeter and Persephone at Eleusis (which may, itself, be a permutation of the Thesmophoria), and the rites for the “Great Gods” at Samothrace. There were priests and priestesses, and even families (gens) tied to maintaining the rites. These also tended to be “one-off,” so one could be initiated to each stage only once.

Others were “repeating” rites, and were usually not tied to a specific place. The best known of these was for Dionysos and/or Orpheus, but Mithras would be a much later example, too. The “mystes” (leaders) of these were not necessarily formal priests/priestesses, and may even have been itinerant. They weren’t necessarily well-regarded socially, either. (The orator Aeschines had shade thrown at him by accusing his mother of having been an actress and performer of initiations, in which Aeschines supposedly helped.)

The rite described in the book is, of course, fictional, as the ancients kept their Mysteries a mystery, and we have no complete account. But we do have “hints and allegations,” if you will, from materials such as gold tablets/leaves (lamellae) from tombs, the Derveni Papyrus (from a grave in Macedonia, which contains “Orphic” theology, see below), or the fescos from the Villa of the Mysteries at Pompeii. As a result, we have a pretty good *general* idea of what went on, but the details, the order, etc., that’s unknown. So I made it up. :-)

Macedonia has produced gold lamellae similar to those found at Pelinna and Pherai in Thessaly, in particular (called “Group D”). These are part of a larger cache of tablets found all over Greater Greece from Macedonia and Thrace to Crete to Thurii in Italy (see below). I used text from the tablets in writing the scene, such as the formula “I am a child of Earth and Starry Heaven.” The tablets come in groups with text ranging from a name alone to bits and pieces of apparent liturgy (?). While some of these are square, others are a diamond shape. They seem to have been put in the hand of the deceased, on the deceased’s mouth (the diamond especially), or on the chest, and acted as “reminders” for the soul as it took its journey to the underworld: how to avoid the river of forgetfulness, what to say to Persephone, etc., in order to get to happy Elysion, not boring ol’ Hades.

There’s no little disagreement as to whether what’s on the tablets reflect a single text or several different traditions. There’s not even agreement as to whether these lamellae are “Orphic,” and what that meant. Dionysic rites were gender segregated, and (it seems) that the female rites did NOT use wine–a common misconception, and by the Hellenistic era, may have even been celebrated in buildings, not the forest. We have inscriptions suggesting as much. Instead of alcohol, the women danced themselves into a frenzy. They also weren’t really eating raw meat. The meat seems to have been tossed into a pit or bowl “for Dionysos.” So it wasn’t the wild crazy stuff described in the Bakkhai, which is a play and mythical. We can’t and shouldn’t assume it reflects what people were actually doing. That said, there is mention in Plutarch, et al., that the Macedonian version (mimallones instead of maenads) included the use of tame snakes. The Greeks had a weird relationship with snakes: they had a “house snake” connected to the cult of Zeus Ktesios, but also tended to regard snakes with great suspicion.

What the men were doing is less clear, and here’s where it may fold into “Orphic” rites, whatever that was. The assumption is some of the Orphic stuff was coming down from Thrace, Macedonia’s near neighbor. I’ve got a book Orpheus, the Thracian, but I got it at the museum in Kazanlak, Bulgaria, so it’s not included in the list below, as I doubt it’s obtainable easily, even for libraries.

Introduction to Mysteries generally:

Walter Burkert, Ancient Mystery Cults, Burkert is the “father” of much of the modern treatment of Greek religion, so this is the starting place.

Jan N. Bremmer, Initiation into the Mysteries of the Ancient World. Another big name in the study of Greek religion.

Hugh Bowden, Mystery Cults of the Ancient World; I think his treatment of Eleusis is better than Dionysos, but it’s a good book with images.

Greek Mysteries: the Archaeological and Ritual of Ancient Greek Secret Cults, Michael B. Cosmopoulos, ed., is relatively recent and has a couple chapters on Dionysic cult.

Some intro bibliography on Dionysos:

Richard Seaford, Dionysos, from Routledge’s series on the heros and gods, is a great, short introduction that covers a lot of ground.

Susan Cole, “Finding Dionysos,” in A Companion to Greek Religion, ed. Daniel Ogden, another good introduction, written for a more advanced audience.

More complex treatments of Dionysos:

Masks of Dionysos, Thomas H. Carpenter and Christopher A. Faraone, eds., has articles on the god ranging from theatre to the mysteries.

A Different God? Dionysos and Ancient Polytheism, Renate Schlesier, ed. This (and the one below) are expensive edited collections better sought via ILL.

Redefining Dionysos, Alberto Bernabe, et al., eds., see the chapter “Dionysos versus Orphaeus?” by Marisa Tortorelli Ghidini.

Books on the tablets, the Derveni Papyrus, etc.:

Fritz Graf and Sarah Isles Johnston, Ritual Texts for the Afterlife: Orpheus and the Bacchic Gold Tablets, 2nd ed….start here. It’s a great introduction.

The “Orphic” Gold Tablets and Greek Religion: Further Along the Path, Radcliffe G. Edmonds III, ed. A collection of articles on the tablets from all over the opinion map.

Poetry as Initiation: the Center for Hellenic Studies Syposium on the Derveni Papyrus, Ioanna Papadopoulou and Leonard Mueliner, eds., conference proceedings

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

I rewrote the myth of Theseus and the Minotaur, but in a way were nobody is unhappy.

Theseus paced around his cell. He sighed deeply, very deeply. The next day, he had to face the minotaur. When he had stepped onto the boat that brought him to Crete, weeks earlier, he had thought that he would have figured out how to brave the labyrinth by this point. But alas, his brain was still blank. He sunk to the ground and rested his head against the wall of his cell. He was so tired. What to do, what to do…

He scrambeld to his feet when he heard something in the hallway. He turned his head around, towards the small window in the door. He saw light coming towards him. He blinked. It seemd so…bright. He hadn’t seen light in quite a while. He heard a knock on his door. ‘Theseus?’ a feminine voice asked. Theseus straightend his back.

'Who are you?’

'You are a feisty one. I am princess Ariadne.’ Theseus swallowed.

'What do you want from me?’

'Calm down a little. I can help you defeat the minotaur. Yet… I’ll want something back.’

'How can I trust that you won’t kill me?’

'Theseus, your chances are that I actually help you, or I kill you. If I don’t give you advice, you die tomorrow anyway, so you either take the chance, or you die anyway.'

Theseus didn’t say anything back. 'I take it that you agree.’ He heard the lock of the door open. Ariadne appeared in the door frame. 'Follow me.’

The princess lead him to a secluded part of the palace. 'We can talk here. The guards patrol here at this time.’ She soothed the skirt of her dress. First, there is something you should know. The minotaur is my half-brother.’ Theseus gasped and opened his mouth to say something back, but the princess held up her finger.

'Let me continue. I know Asterion - that is the minotaurs birthname - has the habit of eating humans, when forced by starvation. Yet, when he does not get meat, he eats regular food, the scraps of our dinner. Someone had to bring it to him every day, and that was me. I… I have gotten close to him.’

'He is a monster, though, and you are so young and frail…’

'I am quite certain that I am older than you are and we Princesses train more than people think. Moving on, It would break my heart if he were to be killed.’ Theseus swallowed. The look she gave him didn’t make him feel comfortable. 'Now - it is quite easy to go around this problem,’ she continued, 'Because under the labyrinth there is a corridor system, through which he will be able to escape to the woods on the island. He will be safe there, it is a holy place where hunting is illegal.’

'How do you know all that?’

'I said I had to feed him every day. Do you think I do not know how to walk through the labyrinth? Also, my… mentor showed me the geography of the Island.'

'Alright, that is true, I guess…’ The girl pushed a ball of yarn into his hands.

'Here. This clew of wool will make sure that you do not get lost and that you will find the corridors. It is magic - don’t ask. If Asterion sees it, and you call him by his name, I am sure that he will not charge at you. Tell him I send you.’

'Wait, he can…’

'Understand and speak human language. . If you lead him away, you can use the clew to get back to the entrance of the labyrinth, so you can leave and go back to Athens, with all the others.’

'What if he kills me before I can do all that?’

'He won’t.’ Ariadne got a sword from behind her skirts. 'But, here is my dad’s sword, just to be sure.’ Theseus laughed.

'Well… Thanks.’ He took the sword from her hands. After that, he remembered that Ariadne had told him he had to do something for her in return. 'Uh… You told me I needed to do something for you too.’ She gave him a single nod.

'This might sound weird…’

'Weirder than everything you have already told me?’ She chuckled.

'Depends on how you see it. But, you see, I am actually supposed to get married to the old king of Thrace. He is… known for keeping a lot of misstresses and not treating his wives good. Yet, I have received a… better proposal. One that my father doesn’t agree with. Or know of.’ Theseus raised his eyebrows.

'Of whom, then? One of the servants? Some fisherman?’

'Very funny, Athens Boy. But, no.’ The princess pushed up her sleeve, revealing a small tattoo on the back of her arm. It resembled a bunch of grapes, but Theseus realised that it wasn’t just any small tatoo. It felt like one of the gods. put it there. 'It’s Dionysus…’

'What!?’

'Let me talk. Yet, he can’t take me away from here. I am locked inside the castle at all times and because of an old law, he can’t get me out. Yet, a few days ago, he told me he could take me along with him if I was not on Crete. I have looked at it, and there is a small Island on the way from Athens to Crete, called Naxos. You can leave me there. ’

'So, if I can lead the minotaur to a peaceful place so that I do not die and he doesn’t either, I just… have to take you along and leave you on that island so your boyfriend, who is also the god of madness and wine, can pick you up?’

'Exactly.'

Theseus blinked. 'Sounds way to easy to be true.'

The princess shrugged. 'It is the best for everyone.’

'Then I accept, your majesty.'

'So, we have a deal, my prince?’ She held up her hand.

'We have a deal,’ he said, while giving her a high five.

Theseus breathed in the cool sea air.’ Hmm. Now that’s amazing, don’t you think?’ Ariadne chuckled.

'It certainly is. I would often sneak off to a side of the palace where the fresh air from the ocean could just reach me. But of course, it is nothing compared to being fully surrounded by it.’ Theseus nodded.

'I can understand that. Man, I almost can’t comprehend how easy that whole ordeal turned out to be. Thanks again, Ariadne.’ The princess nodded.

'Hm-hm.’ She narrowed her eyes. 'I think that over there is Naxos.’ Theseus looked at the direction she pointed at. He sighed. 'Yeah, it sure is.’ He turned around.

'Sail towards the island in the distance! We’ll get resources for the rest of the trip there!’ He called out. His first mate nodded, and begun shouting instructions to the rest of the crew.

Theseus sighed again and turned back to Ariadne. She looked excited. 'You know, I wish you and your boyfriend good luck, together.’ She looked at him and smiled.

'Thanks, Theseus. If you ever find a lover, I wish you the same.’ She chuckled again. 'I think I’ll miss you… for a bit.’ Theseus laughed.

Same for me, princess. Just a bit, of course.’ They laughed together. She took a very deep breath.

'We’ll have the rest of the trip to the island to still talk, Theseus.’

Theseus carried a barrel filed with fresh water towards the ship. When he was done, he walked out onto the beach one last time. Ariadne was waiting there. 'Are you sure he is coming?’ She nodded with confidence.

'Yes. When you have left.’ He slowly nodded.

Ariadne put a hand on his shoulder. I feel his presence, Theseus. You have my eternal thanks for bringing me here.’

'You’re welcome.’ She smiled and gave him a kiss on the cheek.

'I hope I get to see you again some day.'

'Me too. ’ Ariadne let her hand slip of his shoulder. Theseus put a step back, turned around and slowly walked back to the boat.

He waved at her one last time, when she was just a spec in the distance. She waved back, before turning around and walking towards something Theseus couldn’t fully see. He took a deep breath. 'Guess he did come for her after all,’ he said to himself, feeling relieved.

'I think he thinks you didn’t come for me,’ Ariadne said, while she gracefully twirled around after that last wave.

'I did, though. And you too, apparently. To be honest, I wasn’t sure he’d let you go,’ Dionysus answered. She snickered and fell into his arms.

'Gods have a certain aura, don’t you know that? and I can sense yours from a few hundred metres away. That’s how I knew you were coming.’ Dionysus snickered.

'Good to know that.’ He gently pushed her out of his arms, so he could look at her. He cupped her face. 'You’re even more beautiful when you are free.' Ariadne put a hand on his.

'That’s good to know, because that is how I will be spending the rest of my life.’ Dionysus nodded and kissed her on the forehead.

I promise you that it will be the rest of your life, Ariadne. I promise.’

25 notes

·

View notes

Photo

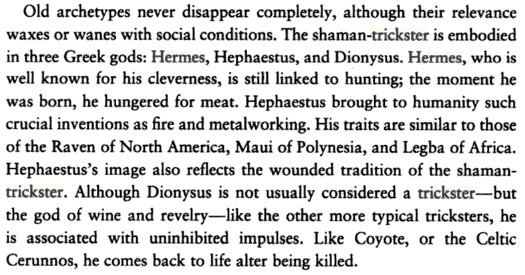

Mark Stefik, Internet Dreams: Archtypes, Myths, and Metaphors

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

I wonder what the reason is that all possible children of Hades and Persephone are also attributed to other parentages?

it’s weird.

110 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

When i first started to get into hellenistic worship i found this hymn to Dionysus which i really like! I didn’t even realize it was a orphic hymn till today which is also cool cause I’ve been looking into orphic stuff and the dionysian mysteries

23 notes

·

View notes

Note

Persephone ate the pomegranate seeds willingly? Why?

I talk a lot about why she would eat the seeds willingly here and here. And there’s another bit I wrote about female agency in the Bronze Age here.

But the long and short of those three wordy essays on that idea is this: Persephone was a goddess and one who was deeply feared and respected by the Greeks. Before she became the Iron Queen of the Underworld, she presided over vegetation and fertility as the embodiment of spring (Karpophoros) and would have known what those seeds meant.

And by explicating the Homeric Hymn to Demeter, her first appearance in written record, we see that she changed Hades himself. The story begins with him snatching her unwillingly and carrying her away to the Underworld in the way a bride would traditionally be taken to her new husband’s home. But by the time Persephone leaves, he has this to say:

“Go now, Persephone, to your dark-robed mother, go, and feel kindly in your heart towards me: be not so exceedingly cast down; for I shall be no unfitting husband for you among the deathless gods, that am own brother to father Zeus. And while you are here, you shall rule all that lives and moves and shall have the greatest rights among the deathless gods: those who defraud you and do not appease your power with offerings, reverently performing rites and paying fit gifts, shall be punished for evermore.”

It is right after this scene that he slips her the pomegranate seeds. In this scene Hermes has come to bring Persephone back to grieving Demeter, and Hades doesn’t just say “here, Hermes I’ll return Zeus his property” but addresses and cajoles Persephone herself and offers her equal rulership over his domain something that would have been un-fucking-heard-of in a society where women were seen as chattel, as a way to simply produce sons.

But why did she eat the seeds? We know she didn’t do it because she was hungry. It says in the Illiad that gods do not require bread or wine as mankind does.

When she eats the seeds she is called “wise Persephone”, casting away doubt that it was done by mistake.

And she eats the seeds ONLY after Hades offers her timai, honor, and a chance to be something more than what she was in the world above: kore, a name that simply means ‘maiden’ or ‘girl’. If she hadn’t eaten the seeds, it would have compelled her to “remain continually with grave, dark-robed Demeter”, and she would have been a maiden without timai once more instead of the ruler over the dead that the Greeks feared and respected utterly.

Persephone herself says later that Zeus had given her to Hades with métis (wisdom), showing that she too was transformed by her time with Hades, and believed him to be a fitting husband. A good match for her. The alliteration of ‘dark-haired Hades and noble Persephone’ in how Hermes addressed them when he found them together would have also tipped off the ancient audience listening to the hymn that they were well matched.

Because she was a goddess of vegetation who would know the consequences of eating the food of the Underworld, because she held a place of such importance in the pantheon, and because she only did it after Hades promised her equal rule as Queen, I believe that Persephone ate the seeds conscientiously and willingly.

8K notes

·

View notes